Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sinhala language

View on Wikipedia

| Sinhala | |

|---|---|

| සිංහල භාෂාව (Siṁhala Bhashava) | |

| |

| Pronunciation | IPA: [ˈsiŋɦələ] |

| Native to | Sri Lanka |

| Ethnicity | Sinhalese |

| Speakers | L1: 16 million (2021)[1] L2: 4 million (2021)[1] Total: 20 million (2021)[1] |

| Dialects |

|

| Official status | |

Official language in | Sri Lanka |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | si |

| ISO 639-2 | sin |

| ISO 639-3 | sin |

| Glottolog | sinh1246 |

| Linguasphere | 59-ABB-a |

Sinhala is the majority language where the vast majority are first language speakers

| |

Sinhala (/ˈsɪnhələ, ˈsɪŋələ/ SIN-hə-lə, SING-ə-lə;[2] Sinhala: සිංහල, siṁhala, [ˈsiŋɦələ]),[3] sometimes called Sinhalese (/ˌsɪn(h)əˈliːz, ˌsɪŋ(ɡ)əˈliːz/ SIN-(h)ə-LEEZ, SING-(g)ə-LEEZ), is an Indo-Aryan language primarily spoken by the Sinhalese people of Sri Lanka, who make up the largest ethnic group on the island, numbering about 16 million.[4][1] It is also the first language of about 2 million other Sri Lankans, as of 2001.[5] It is written in the Sinhalese script, a Brahmic script closely related to the Grantha script of South India.[6] The language has two main varieties, written and spoken, and is a notable example of the linguistic phenomenon known as diglossia.[7]

Sinhala is one of the official and national languages of Sri Lanka. Along with Pali, it played a major role in the development of Theravada Buddhist literature.[1]

Early forms of the Sinhalese language are attested to as early as the 3rd century BCE.[8] The language of these inscriptions, still retaining long vowels and aspirated consonants, is a Prakrit similar to Magadhi, a regional associate of the Middle-Indian Prakrits that had been spoken during the lifetime of the Buddha.[9] The most closely related languages to Sinhalese are the Vedda language and the Maldivian languages; the former is an endangered indigenous creole still spoken by a minority of Sri Lankans, which mixes Sinhalese with an isolate of unknown origin. Old Sinhalese borrowed various aspects of Vedda into its main Indo-Aryan substrate.[10]

Etymology

[edit]Sinhala (Siṅhala) is a Sanskrit term; the corresponding Middle Indo-Aryan (Eḷu) word is Sīhala. The name is a derivative of the Sanskrit word for 'lion' siṁha.[12] The name is sometimes glossed as 'abode of lions', and attributed to a supposed former abundance of lions on the island.[13]

History

[edit]According to the chronicle Mahāvaṃsa, written in Pali, Prince Vijaya of the Vanga Kingdom and his entourage merged in Sri Lanka with later settlers from the Pandya kingdom.[14][15][16] In the following centuries, there was substantial immigration from Eastern India, including additional migration from the Vanga Kingdom (Bengal), as well as Kalinga and Magadha.[17] This influx led to an admixture of features of Eastern Prakrits.[citation needed]

Stages of historical development

[edit]The development of Sinhala is divided into four epochs:[18]

- Elu Prakrit (3rd c. BCE to 4th c. CE)

- Proto-Sinhala (4th c. CE to 8th c. CE)

- Medieval Sinhala (8th c. CE to 13th c. CE)

- Modern Sinhala (13th c. CE to the present)

Phonetic development

[edit]The most important phonetic developments of Sinhala include:

- the loss of aspiration as a distinction for plosive consonants (e.g. kanavā "eating" corresponds to Sanskrit khādati, Hindustani khānā)

- the loss of original vowel length distinction; long vowels in the modern language are found in loanwords (e.g. vibāgaya "exam" < Sanskrit vibhāga) or as a result of sandhi, either after elision of intervocalic consonants (e.g. dānavā "to put" < damanavā) or in originally compound words.

- the simplification of consonant clusters and geminate consonants into geminates and single consonants respectively (e.g. Sanskrit viṣṭā "time" > Helu viṭṭa > Modern Sinhala viṭa)

- development of /tʃ/ to /s/ and/or /ɦ/ (e.g. san̆da/han̆da "moon" corresponds to Sanskrit candra) and development of /dʒ/ to /d/ (e.g. dæla "web" corresponds to Sanskrit jāla)

- development of prenasalized consonants from Sanskrit nasal + voiced stops (as in han̆da)[19]

- retention of initial /w/ and /j/, the latter only shared with Kashmiri (as in viṭa and yutu "fit, proper" < Sanskrit yukta)[20]

Western vs. Eastern Prakrit features

[edit]According to Wilhelm Geiger, an example of a possible Western feature in Sinhala is the retention of initial /v/ which developed into /b/ in the Eastern languages (e.g. Sanskrit viṁśati "twenty", Sinhala visi-, Hindi bīs). This is disputed by Muhammad Shahidullah who says that Helu Prakrit branched off from the Eastern Prakrits prior to this change. He cites the edicts of Ashoka, no copy of which shows this sound change.[21]

An example of an Eastern feature is the ending -e for masculine nominative singular (instead of Western -o) in Helu. There are several cases of vocabulary doublets, one example being the words mæssā ("fly") and mækkā ("flea"), which both correspond to Sanskrit makṣikā but stem from two regionally different Prakrit words macchiā (Western Prakrits) and makkhikā (as in Eastern Prakrits like Pali).

Pre-1815 Sinhalese literature

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2024) |

In 1815, the island of Ceylon came under British rule. During the career of Christopher Reynolds as a Sinhalese lecturer at the School of African and Oriental Studies, University of London, he extensively researched the Sinhalese language and its pre-1815 literature. The Sri Lankan government awarded him the Sri Lanka Ranjana medal for his work. He wrote the 377-page An anthology of Sinhalese literature up to 1815, selected by the UNESCO National Commission of Ceylon[22]

Substratum influence in Sinhala

[edit]According to Wilhelm Geiger, Sinhala has features that set it apart from other Indo-Aryan languages. Some of the differences can be explained by the substrate influence of the parent stock of the Vedda language.[23] Sinhala has many words that are only found in Sinhala, or shared between Sinhala and Vedda and not etymologically derivable from Middle or Old Indo-Aryan. Possible examples include kola for leaf in Sinhala and Vedda (although others suggest a Dravidian origin for this word.[24][25][26]), dola for pig in Vedda and offering in Sinhala. Other common words are rera for wild duck, and gala for stones (in toponyms used throughout the island, although others have also suggested a Dravidian origin).[27][28][29] There are also high frequency words denoting body parts in Sinhala, such as olluva for head, kakula for leg, bella for neck and kalava for thighs, that are derived from pre-Sinhalese languages of Sri Lanka.[30] The oldest known Sinhala grammar, Sidatsan̆garavā, written in the 13th century CE, recognised a category of words that exclusively belonged to early Sinhala. The grammar lists naram̆ba (to see) and koḷom̆ba (fort or harbour) as belonging to an indigenous source. Koḷom̆ba is the source of the name of the commercial capital Colombo.[31][32]

South Dravidian substratum influence

[edit]The consistent left branching syntax and the loss of aspirated stops in Sinhala is attributed to a probable South Dravidian substratum effect.[33] This has been explained by a period of prior bilingualism:

"The earliest type of contact in Sri Lanka, not considering the aboriginal Vedda languages, was that which occurred between South Dravidian and Sinhala. It seems plausible to assume prolonged contact between these two populations as well as a high degree of bilingualism. This explains why Sinhala looks deeply South Dravidian for an Indo-Aryan language. There is corroboration in genetic findings."[34]

Influences from neighbouring languages

[edit]In addition to many Tamil loanwords, several phonetic and grammatical features also present in neighbouring Dravidian languages set modern spoken Sinhala apart from its Northern Indo-Aryan relatives. These features are evidence of close interactions with Dravidian speakers. Some of the features that may be traced to Dravidian influence are:

- the loss of aspiration

- the use of the attributive verb of kiyana "to say" as a subordinating conjunction with the meanings "that" and "if", e.g.:

ඒක

ēka

it

අලුත්

aḷut

new

කියලා

kiyalā

having-said

මම

mama

I

දන්නවා

dannavā

know

"I know that it is new."

ඒක

ēka

it

අලුත්

aḷut

new

ද

da

Q

කියලා

kiyalā

having-said

මම

mama

I

දන්නේ

dannē

know-EMP

නැහැ

næhæ

not

"I do not know whether it is new."

European influence

[edit]As a result of about 3 centuries of colonial rule, interaction, settlement and assimilation, modern Sinhala contains some Portuguese, Dutch and English loanwords.

Influences on other languages

[edit]Macanese Patois or Macau Creole (known as Patuá to its speakers) is a creole language derived mainly from Malay, Sinhala, Cantonese, and Portuguese, which was originally spoken by the Macanese people of the Portuguese colony of Macau. It is now spoken by a few families in Macau and in the Macanese diaspora.[citation needed]

The language developed first mainly among the descendants of Portuguese settlers who often married women from Malacca and Sri Lanka rather than from neighbouring China, so the language had strong Malay and Sinhala influence from the beginning.

Accents and dialects

[edit]The Sinhala language has different types of variations which are commonly identified as dialects and accents. Among those variations, regional variations are prominent. Some of the well-known regional variations of Sinhala language are:[35]

- The Uva Province variation (Monaragala, Badulla).

- The southern variation (Matara, Galle).

- The up-country variation (Kandy, Matale).

- The Sabaragamu variation (Kegalle, Balangoda).

Uva regional variation in relation to grammar

[edit]People from Uva province also have a unique linguistic variation in relation to the pronunciation of words. In general, Sinhala singular words are pluralized by adding suffixes like -o, -hu, -wal or -waru. But when it comes to Monaragala, the situation is somewhat different as when nouns are pluralized a nasal sound is added.[35]

| General way of pluralizing Sinhala words | The way Uva people pluralize words |

|---|---|

kàntawǝ ǝ woman kantàwò ò women |

lindha

well lindha+n lindhan wells |

potǝ ǝ book pot Ø books |

oya

stream oya+n oyan streams |

lindhǝ ǝ well lindhǝ+wal + wal wells |

Southern variation

[edit]The Kamath language (an indigenous language of paddy culture) used by the Southerners is somewhat different from the 'Kamath language' used in other parts (Uva, Kandy) of Sri Lanka as it is marked with a systematic variation; 'boya' at the end of the majority of nouns as the examples below show.[35]

- Crops: Kurakkan boya (bran)

- Rambakan boya (banana)

- Tools: Thattu boya (bucket)

- Other words: Nivahan boya (home)

Here the particular word 'boya' means 'a little' in the Southern region and at the end of most of nouns, 'boya' is added regularly. This particular word 'boya' is added to most words by the Southern villages as a token of respect towards the things (those things can be crops, tools etc.) they are referring to.

Kandy, Kegalle and Galle people

[edit]| The common Sinhala variation | Different regional variations of Sinhala language | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ayye heta wapuranna enwada?

(Elder Brother, Are you coming to sow tomorrow?) |

Ayya heta wapuranta enawada? (Kandy)

Ayye heta wapuranda enawada? (Kegalle) Ayye heta wapuranna enawai? (Galle) |

Here the Kandy people say 'Ayya' while the Kegalle and Galle people say 'Ayye'.

Also, Kandy people add a 'ta' sound at the end of verbs while the Kegalle people add a 'da' sound. But Galle people's regional variation is not visible in relation to this particular verb; 'wapuranawa' (to sow). Yet their unique regional variation is visible in relation to the second verb which is 'enawai' (coming) as they add 'ai' at the end of most verbs. A point to remember the ‘ai’ at the end of a word could also be used in the context of future tense |

Even though the Kandy, Kegalle and Galle people pronounce words with slight differences, the Sinhalese can understand the majority of the sentences.

Diglossia

[edit]In Sinhala there is distinctive diglossia, where the literary language and the spoken language differ from each other in significant ways. While the lexicon can vary continuously between formal and informal contexts, there is a sharp contrast between two distinct systems for syntax and morphology. The literary language is used in writing for all forms of prose, poetry, and for official documents, but also orally for TV and radio news broadcasts. The spoken language is used in everyday life and spans informal and formal contexts. Religious sermons, university lectures, political speeches, and personal letters occupy an intermediate space where features from both spoken and literary Sinhala are used together, and choices about which to include give different impressions of the text.[36]

A number of syntactic and morphological differences exist between the two varieties. The most apparent difference is the absence of subject-verb agreement in spoken Sinhala. Agreement is the hallmark of literary Sinhala, and is the sole characteristic used in determining whether a given example of Sinhala is in the spoken or literary variety. Other distinctions include:

Writing system

[edit]

The Sinhala script, Sinhala hodiya, is based on the ancient Brahmi script, and is thus a Brahmic script along with most Indian scripts and many Southeast Asian scripts. The Sinhala script is closely related to Grantha script and Khmer script, but it has also taken some elements from the related Kadamba script.[38][6]

The writing system for Sinhala is an abugida, where the consonants are written with letters while the vowels are indicated with diacritics (pilla) on those consonants, unlike alphabets like English where both consonants and vowels are full letters, or abjads like Urdu where vowels need not be written at all. Also, when a diacritic is not used, an "inherent vowel", either /a/ or /ə/, is understood, depending on the position of the consonant within the word. For example, the letter ක k on its own indicates ka, realized as /ka/ in stressed syllables and /kə/ in unstressed syllables. The other monophthong vowels are written: කා /kaː/, කැ /kæ/, and කෑ /kæː/ (after the consonant); කි /ki/ and කී /kiː/ (above the consonant); කු /ku/ and කූ /kuː/ (below the consonant); කෙ /ke/ and කේ /keː/ (before the consonant); and lastly, කො /ko/ and කෝ /koː/ (surrounding the consonant). For simple /k/ without a following vowel, a vowel-cancelling diacritic called හල් කිරීම (/hal kiriːmə/, hal kirima) is used, creating ක් /k/.

There are also a few diacritics for consonants, such as /r/ in special circumstances, although the tendency now is to spell words with the full letter ර /r/, with a hal kirima on whichever consonant has no vowel following it. One word that is still spelt with an "r" diacritic is ශ්රී, as in ශ්රී ලංකාව (Śri Lankāwa). The "r" diacritic is the curved line under the first letter ("ශ" → "ශ්ර"). A second diacritic representing the vowel sound /iː/ completes the word ("ශ්ර" → "ශ්රී").

Several of these diacritics occur in two or more forms, and the form used depends on the shape of the consonant letter. Vowels also have independent letters, but these are only used at the beginning of words where there is no preceding consonant to add a diacritic to.

The complete script consists of about 60 letters, 18 for vowels and 42 for consonants. However, only 57 (16 vowels and 41 consonants) are required for writing colloquial spoken Sinhala (śuddha Sinhala).[citation needed] The rest indicate sounds that have been merged in the course of linguistic change, such as the aspirates, and are restricted to Sanskrit and Pali loan words. One letter (ඦ), representing the sound /ⁿd͡ʒa/, is attested in the script, although only a few words using this letter are known (වෑංඦන, ඉඦූ).

The Sinhala script is written from left to right, and is mainly used for Sinhala. It is also used for the liturgical languages Pali and Sanskrit, which are important in Buddhism and academic works. The alphabetic sequence is similar to those of other Brahmic scripts:

Phonology

[edit]| External audio | |

|---|---|

Sinhala has a smaller consonant inventory than most Indo-Aryan languages, but simultaneously has a larger vowel inventory than most. As an insular Indo-Aryan language, it and Dhivehi have features divergent from rest of the Indo-Aryan languages. Sinhala's nasal consonants are unusual among Indo-Aryan languages for lacking the retroflex nasal /ɳ/ while retaining nasals in the other four positions. Sinhala and Dhivehi are together unique for having prenasalised consonants, which are not found in any other Indo-Aryan language.

Consonants

[edit]Sinhala has prenasalised consonants, or 'half nasal' consonants, but has lost the distinction between aspirated and unaspirated stops. It still has the distinction between dental/alveolar and retroflex stops. A short homorganic nasal occurs before a voiced stop, it is both shorter than a nasal alone and shorter than a sequence of nasal plus stop.[39] The nasal is syllabified with the onset of the following syllable, which means that the moraic weight of the preceding syllable is left unchanged. For example, tam̆ba 'copper' contrasts with tamba 'boil'. Sinhala is one of only three languages reported to have a contrast between prenasalized consonants and their corresponding clusters, along with Fula and Selayarese, although the nature of this contrast is debated.[40][41] For example,

| Sinhala script | IPA | ISO 15919 | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| කද | [ka.d̪ə] | kada | shoulder pole |

| කඳ | [ka.ⁿd̪ə] | kan̆da | trunk |

| කන්ද | [kan̪.d̪ə] | kanda | hill |

| කන | [ka.nə] | kana | earhill |

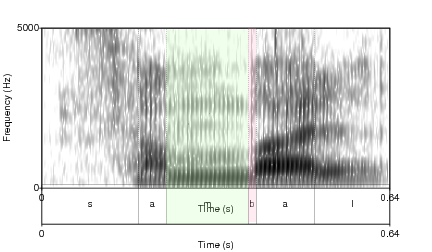

Sri Lankan Malay has been in contact with Sinhala a long time and has also developed prenasalized stops. The spectrograms on the right show the word gambar with a prenasalized stop and the word sambal with a sequence of nasal+voiced stop, yet not prenasalized. The difference in the length of the [m] part is clearly visible. The nasal in the prenasalized word is much shorter than the nasal in the other word.

All consonants other than the prenasalised consonants, /ŋ/, /ɸ/, /h/, and /ʃ/ can be geminated (occur as double consonants), but only between vowels.[39] In contexts that otherwise trigger gemination, prenasalised consonants become the corresponding nasal-voiced consonant sequence (e.g. /ⁿd/ is replaced with nd).[42]

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |||

| Stop/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | ʈ | tʃ | k | |

| voiced | b | d | ɖ | dʒ | ɡ | ||

| prenasalised | ᵐb | ⁿd | ᶯɖ | (ⁿdʒ) | ᵑɡ | ||

| Fricative | (f~ɸ) | s | (ʃ) | h | |||

| Trill | r | ||||||

| Approximant | ʋ | l | j | ||||

/ʃ/ is found in learned borrowings from Sanskrit, including in the honorific ශ්රී (śrī), found in phrases including the country's name, Sri Lanka (ශ්රී ලංකා, /ʃriː laŋkaː/). /f~ɸ/ is restricted to loans, typically for English. They are commonly sometimes replaced by /s/ and /p/ respectively. Some speakers use [f], as in English, and some use [ɸ] due to its similarity to the native /p/.

Vowels

[edit]

Sinhala has seven vowel qualities, with a phonemic vowel length distinction between long and short for all qualities, giving a total inventory of 14 vowels. The long vowel /əː/ is not present in native Sinhala words, but instead is found in certain English loanwords. Like in non-rhotic dialects of English, this long vowel can be represented by the short vowel followed by an ⟨r⟩ (ර්), as in ෂර්ට් /ʃəːʈ/ ("shirt").[39]

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | i | iː | u | uː | ||

| Mid | e | eː | ə | (əː) | o | oː |

| Open | æ | æː | a | aː | ||

/a/ and /ə/ have a largely complementary distribution, found primarily in stressed and unstressed syllables, respectively. However, there are certain contrasting pairs between the two phonemes, particularly between homographs කර /karə/ ("shoulder") and කර /kərə/ ("to do"). In writing, /a/ and /ə/ are both spelt without a vowel sign attached to the consonant letter, so the patterns of stress in the language must be used to determine the correct pronunciation. Stress is largely predictable and only contrastive between words in relatively few cases, so this does not present a problem for determining the pronunciation of a given word.[43]

Most Sinhala syllables are of the form CV. The first syllable of each word is stressed, with the exception of the verb කරනවා /kərənəˈwaː/ ("to do") and all of its inflected forms where the first syllable is unstressed. Syllables using long vowels are always stressed. The remainder of the syllables are unstressed if they use a short vowel, unless they are immediately followed by one of: a CCV syllable, final /j(i)/ (-යි), final /wu/ (-වු), or a final consonant without a following vowel. The sound /ha/ is always stressed, except after the vowel sound /i/ (-ඉ) and not before a consonant without a following vowel.[44]

Nasalisation of vowels is common in certain environments, particularly before a prenasalised consonant. Nasalised /ãː/ and /æ̃ː/ exist as marginal phonemes, only present in certain interjections.[39]

Phonotactics

[edit]Native Sinhalese words are limited in syllable structure to (C)V(C), V̄, and CV̄(C), where V is a short vowel, V̄ is a long vowel, and C is a consonant. Exceptions exist for the marginal segment CC.[42] Prenasalised plosives are restricted to occurring intervocalically, and cannot end a syllable. Much more complicated consonant clusters are allowed in loan words, particularly from Sanskrit and English, an example being ප්රශ්නය praśnaya ("question").[45] Words cannot end in nasals other than /ŋ/.[46] Because of historical loss of the fricative /h/ in the suffix /-hu/, /-u/ at the end of a word behaves as its own syllable.[42]

Morphology

[edit]Nominal morphology

[edit]The main features marked on Sinhala nouns are case, number, definiteness and animacy.

Cases

[edit]Sinhala distinguishes several cases. The five primary cases are the nominative, accusative, dative, genitive, and ablative. Some scholars also suggest that it has a locative and instrumental case. However, for inanimate nouns the locative and genitive, and instrumental and ablative, are identical. In addition, for animate nouns these cases formed by placing atiŋ ("with the hand") and laᵑgə ("near") directly after the nominative.

The brackets with most of the vowel length symbols indicate the optional shortening of long vowels in certain unstressed syllables.

| animate | inanimate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| singular | plural | singular | plural | |

| nominative | miniha(ː) | minissu | potə | pot |

| accusative | miniha(ː)wə | minissu(nwə) | ||

| dative | miniha(ː)ʈə | minissu(ɳ)ʈə | potəʈə | potwələʈə |

| genitive | miniha(ː)ge(ː) | minissu(ŋ)ge(ː) | pote(ː) | potwələ |

| locative | miniha(ː) laᵑgə | minissu(n) laᵑgə | ||

| ablative | miniha(ː)geŋ | minissu(n)geŋ | poteŋ | potwaliŋ |

| instrumental | miniha(ː) atiŋ | minissu(n) atiŋ | ||

| vocative | miniho(ː) | minissuneː | - | - |

| Gloss | 'man' | 'men' | 'book' | 'books' |

Number marking

[edit]Forming plurals in Sinhala is unpredictable. In Sinhala animate nouns, the plural is marked with -o(ː), a long consonant plus -u, or with -la(ː). Most inanimates mark the plural through disfixation. Loanwords from English mark the singular with ekə, and do not mark the plural. This can be interpreted as a singulative number.

| SG | ammaː | deviyaː | horaː | potə | reddə | kantoːruvə | satiyə | bus ekə | paːrə |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PL | amməla(ː) | deviyo(ː) | horu | pot | redi | kantoːru | sati | bus | paːrəval |

| Gloss | 'mother(s)' | 'god(s)' | 'thie(f/ves)' | 'book(s)' | 'cloth(es)' | 'office(s)' | 'week(s)' | 'bus(es)' | 'street(s)' |

On the left hand side of the table, plurals are longer than singulars. On the right hand side, it is the other way round, with the exception of paːrə "street". [+Animate] lexemes are mostly in the classes on the left-hand side, while [-animate] lexemes are most often in the classes on the right hand.

Indefinite article

[edit]The indefinite article is -ek for animates and -ak for inanimates. The indefinite article exists only in the singular, where its absence marks definiteness. In the plural, (in)definiteness does not receive special marking.[citation needed]

Verbal morphology

[edit]Sinhala distinguishes three conjugation classes. Spoken Sinhala does not mark person, number or gender on the verb (literary Sinhala does). In other words, there is no subject–verb agreement.

| 1st class | 2nd class | 3rd class | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| verb | verbal adjective | verb | verbal adjective | verb | verbal adjective | |

| present (future) | kanəwaː | kanə | arinəwaː | arinə | pipenəwaː | pipenə |

| past | kæːwaː | kæːwə | æriyaː | æriyə | pipunaː | pipunə |

| anterior | kaːlaː | kaːpu | ærəlaː | ærəpu | pipilaː | pipicca |

| simultaneous | kanə kanə / ka kaa(spoken) | arinə arinə / æra æra(spoken) | pipenə pipenə/ pipi pipi(spoken) | |||

| infinitive | kannə/kanḍə | arinnə/arinḍə | pipennə/pipenḍə | |||

| emphatic form | kanneː | arinneː | pipenneː | |||

| gloss | eat | open | blossom | |||

Syntax

[edit]- Left-branching language (see branching), which means that determining elements are usually put in front of what they determine (see example below).

- An exception to this is formed by statements of quantity which usually stand behind what they define.

මල්

/mal

flowers

හතර

hatərə/

four

"the four flowers"

(it can be argued that the numeral is the head in this construction, and the flowers the modifier, so that a more literal English rendering would be "a floral foursome")

- SOV (subject–object–verb) word order, common to most left-branching languages.

- As is common in left-branching languages, it has no prepositions, only postpositions (see Adposition).

පොත

/potə

book

යට

jaʈə/

under

"under the book"

- Sinhala has no copula. There are two existential verbs, which are used for locative predications, but these verbs are not used for predications of class-membership or property-assignment, unlike English is.

මම

/mamə

I

පොහොසත්

poːsat/

rich

"I am rich"

- There are almost no conjunctions as English that or whether, but only non-finite clauses that are formed by the means of participles and verbal adjectives.

පොත්

/pot

books

ලියන

liənə

writing

මිනිසා

minisa/

man

"The man who writes books"

Semantics

[edit]There is a four-way deictic system (which is rare): There are four demonstrative stems (see demonstrative pronouns):

- මේ /meː/ "here, close to the speaker"

- ඕ /oː/ "there, close to the person addressed"

- අර /arə/ "there, close to a third person, visible"

- ඒ /eː/ "there, close to a third person, not visible"

Use of තුමා (thuma)

[edit]Sinhalese has an all-purpose odd suffix තුමා (thuma) which when suffixed to a pronoun creates a formal and respectful tone in reference to a person. This is usually used in referring to politicians, nobles, and priests.

e.g. oba thuma (ඔබ තුමා) - you (vocative, when addressing a minister, high-ranking official, or generally showing respect in public etc.)

ජනාධිපති

janadhipathi

තුමා

thuma

the president (third person)

Discourse

[edit]Sinhala is a pro-drop language: any arguments of a sentence can be omitted when they can be inferred from context. This is not only true for subject – as in Italian, for instance – but also objects and other parts of the sentence can be "dropped" in Sinhala if they can be inferred. In that sense, Sinhala can be called a "super pro-drop language", like Japanese.

කොහෙද

koɦedə

where

ගියේ

ɡie

went

can mean "where did I/you/he/she/we... go"

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Sinhala language at Ethnologue (28th ed., 2025)

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student's Handbook

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing 2011". www.statistics.gov.lk. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing 2001" (PDF). Statistics.gov.lk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ a b Jayarajan, Paul M. (1 January 1976). History of the Evolution of the Sinhala Alphabet. Colombo Apothecaries' Company, Limited.

- ^ Paolillo, John C. (1997). "Sinhala Diglossia: Discrete or Continuous Variation?". Language in Society. 26 (2): 269–296. doi:10.1017/S0047404500020935. ISSN 0047-4045. JSTOR 4168764. S2CID 144123299.

- ^ Prof. Senarat Paranavithana (1970), Inscriptions of Ceylon Volume I – Early Brāhmī Inscriptions

- ^ Dias, Malini (2020). The language of the Early Brahmi inscriptions of Sri Lanka# Epigraphical Notes Nos.22-23. Department of Archaeology. pp. 12–19. ISBN 978-955-7457-30-7.

- ^ Gair, James W. (1968). "Sinhalese Diglossia". Anthropological Linguistics. 10 (8): 1–15. ISSN 0003-5483. JSTOR 30029181.

- ^ "Sigiri Graffiti: poetry on the mirror-wall". Lanka Library. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ^ Caldwell, Robert (1875), A comparative grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian Family of Languages, London: Trübner & Co., p. 86

- ^ The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British and Foreign India, China, and Australia. Vol. 20. Parbury, Allen, and Company. 1836. p. 30.

- ^ "The Coming of Vijaya". The Mahavamsa. 8 October 2011.

- ^ "The Consecrating of Vijaya - the island of Lanka - Kuvani". The Mahavamsa. 8 October 2011. Archived from the original on 20 June 2023.

- ^ Gananath Obeyesekere, "Buddhism, ethnicity and Identity: A problem of Buddhist History", in Journal of Buddhist Ethics, 10, (2003): 46.

- ^ "Sri Lanka: A Short History of Sinhala Language". WWW Virtual Library Sri Lanka. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ Geiger, Wilhelm. "Chronological Summary of the Development of the Sinhalese Language". Zeitschrift Für Vergleichende Sprachforschung Auf Dem Gebiete Der Indogermanischen Sprachen 76, no. 1/2 (1959): 52–59. JSTOR 40848039.

- ^ Geiger 1938, p. 68

- ^ Geiger 1938, p. 79

- ^ Shahidullah, Muhammad. "The Origin of the Sinhalesé Language". The Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland 8, no. 1 (1962): 108–11. JSTOR 45377492.

- ^ Gombrich, Richard (1970). "UNESCO Collection of Representative Works, Sinhalese Series". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 34 (3). London: George Allen and Unwin Limited: 623–624. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00128812.

- ^ Gair 1998, p. 4

- ^ M.H. Peter Silva, Influence of Dravida on Sinhalese, University of Oxford. Faculty of Oriental Studies 1961, Thesis (D.Phil.) p. 152

- ^ University of Madras Tamil Lexicon, "குழை kuḻai".

- ^ TamilNet, Know the Etymology: 334, Place Name of the Day: 23 March 2014, "Kola-munna, Anguna-kola-pelessa".

- ^ "kal (kaṟ-, kaṉ-)". A Dravidian Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2 February 2022.

- ^ Tuttle, Edwin H. "Dravidian Researches". The American Journal of Philology, vol. 50, no. 2, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1929, pp. 138–55, doi:10.2307/290412.

- ^ Van Driem 2002, p. 230

- ^ Indrapala 2007, p. 45

- ^ Indrapala 2007, p. 70

- ^ Gair 1998, p. 5

- ^ James W Gair - Sinhala, an Indo-Aryan isolate (1996) https://archive.org/details/sinhala-an-indo-aryan-isolate-prof.-james-w.-gair pp.5-11

- ^ Umberto Ansaldo, Sri Lanka and South India, The Cambridge Handbook of Areal Linguistics (2017), pp.575-585

- ^ a b c d Kahandgamage, Sandya (2011). Gove basa. Nugegoda: Sarasavi.

- ^ Paolillo, John C. (1997). "Sinhala Diglossia: Discrete or Continuous Variation?". Language in Society. 26 (2): 269–296. doi:10.1017/S0047404500020935. ISSN 0047-4045. JSTOR 4168764. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ Paolillo, John C. (2000). "Formalizing Formality: An Analysis of Register Variation in Sinhala". Journal of Linguistics. 36 (2): 215–259. doi:10.1017/S0022226700008148. ISSN 0022-2267. JSTOR 4176592. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ "Ancient Scripts: Sinhala". www.ancientscripts.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d Karunatillake, W. S. (1998). An Introduction to Spoken Sinhala (2 ed.). Colombo: M. D. Gunasena & Company Ltd. ISBN 955-21-0878-0.

- ^ a b Feinstein, Mark (1979). "Prenasalization and Syllable Structure". Linguistic Inquiry. 10 (2): 245–278. JSTOR 4178108. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Riehl, Anastasia (January 2008). "NC type combination patterns". The Phonology and Phonetics of Nasal Obstruent Sequences (PDF) (PhD thesis). Cornell University. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ a b c Parawahera, Nimal Pannakitti (25 April 1990). Phonology and Morphology of Modern Sinhala (PhD thesis). University of Victoria. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ Wasala, Asanka; Gamage, Kumudu (1996). Research Report on Phonetics and Phonology of Sinhala (PDF). Working Papers 2004-2007 (Technical report). Language Technology Research Laboratory, University of Colombo School of Computing. pp. 473–484.

- ^ Silva, A.W.L. (2008). Teach Yourself Sinhalese. A.W.L. Silva. ISBN 978-955-96926-0-7.

- ^ Rajapaksa Mudiyanselage Wilson Rajapaksa (July 1988). Aspects of the Phonology of the Sinhalese Verb; A Prosodic Analysis (PhD thesis). University of London.

- ^ Crothers, John H.; Lorentz, James P.; Sherman, Donald A.; Vihman, Marilyn M. (1979). Handbook of Phonological Data from a Sample of the World's Languages (Technical report). Stanford Phonology Archive. pp. 160–162.

Bibliography

[edit]- Gair, James: Sinhala and Other South Asian Languages, New York 1998.

- Indrapala, Karthigesu (2007). The evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils in Sri Lanka C. 300 BCE to C. 1200 CE. Colombo: Vijitha Yapa. ISBN 978-955-1266-72-1.

- Perera, H.S.; Jones, D. (1919). A colloquial Sinhalese reader in phonetic transcription. Manchester: Longmans, Green & Co.

- Van Driem, George (15 January 2002). Languages of the Himalayas: An Ethnolinguistic Handbook of the Greater Himalayan Region. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-10390-0.

Further reading

[edit]- Clough, B. (1997). Sinhala English Dictionary (2nd ed.). New Delhi: Asian Educational Services.

- Gair, James; Paolillo, John C. (1997). Sinhala. Newcastle: München.

- Gair, James (1998). Studies in South Asian Linguistics. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509521-0.

- Geiger, Wilhelm (1938). A Grammar of the Sinhalese Language. Colombo.

- Karunatillake, W.S. (1992). An Introduction to Spoken Sinhala. Colombo. [several new editions].

- Zubair, Cala Ann (2015). "Sexual violence and the creation of an empowered female voice". Gender and Language. 9 (2): 279–317. doi:10.1558/genl.v9i2.17909. (Article on the use of slang amongst Sinhalese Raggers.)

External links

[edit]- Charles Henry Carter. A Sinhalese-English dictionary. Colombo: The "Ceylon Observer" Printing Works; London: Probsthain & Co., 1924.

- Simhala Sabdakosa Karyamsaya. Sanksipta Simhala Sabdakosaya. Kolamba : Samskrtika Katayutu Pilibanda Departamentuva, 2007–2009.

- Sinhala Dictionary and Language Translator – Madura Online English

- Kapruka Sinhala dictionary

- "Sigiri Graffiti: poetry on the mirror-wall". Lanka Library. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

Sinhala language

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Etymology

Linguistic Classification

Sinhala is classified as a member of the Indo-Aryan branch within the Indo-Iranian group of the Indo-European language family.[6][7] This placement is determined by its core lexicon, morphology, and syntax, which derive primarily from Middle Indo-Aryan Prakrit forms, such as those attested in early Sri Lankan inscriptions from the 3rd century BCE.[5] Within Indo-Aryan, Sinhala forms part of the Southern or Insular subgroup, distinguished by innovations like prenasalized consonants and specific phonological shifts not shared with continental Indo-Aryan languages.[8] The Insular Indo-Aryan category encompasses Sinhala and the closely related Dhivehi (Maldivian), spoken in the Maldives, reflecting their geographic isolation and shared divergence from mainland Indo-Aryan around the early centuries CE.[9] This subgroup's unity is evidenced by mutual retentions from Proto-Indo-Aryan, including verb conjugation patterns and nominal declensions, despite subsequent areal influences from Dravidian languages like Tamil, which have affected phonology and vocabulary but not altered the fundamental genealogical affiliation.[10] Scholarly consensus, based on comparative reconstruction, affirms Sinhala's Indo-Aryan status over alternative hypotheses linking it more closely to non-Indo-European families, as substrate effects explain convergences without reclassifying the language.[11]Etymological Roots

The name Sinhala, denoting both the ethnic group and their language, originates from the Sanskrit compound siṃhala, derived from siṃha ("lion") combined with the suffix -la, which indicates association or resemblance, yielding a meaning of "lion-pertaining" or "of the lions."[12][13] This etymon first denoted the island of Sri Lanka—referred to in ancient Indian texts as Siṃhala-dvīpa ("Sinhala island")—before extending to its inhabitants and their tongue, reflecting the island's historical identification with leonine symbolism, possibly alluding to abundant wildlife or emblematic banners in early records.[5] In Pali, a Middle Indo-Aryan language influential in the region's Buddhist literature, the term appears as sīhala, preserving the Sanskrit root while adapting to Prakrit phonology, with the earliest attestations in texts like the Parisiṣṭaparvan (12th century CE) linking it to Ravana's lion-emblazoned flag in Lankan lore.[14] Mythological accounts, preserved in chronicles such as the Mahāvaṃsa (compiled circa 5th century CE), attribute the name to the legendary progenitor Vijaya, whose father Sinhabāhu ("lion-arms") embodies the simian-leonine motif, though these narratives blend etiology with symbolic reinforcement rather than direct linguistic causation.[15] The root siṃha itself traces to Proto-Indo-European *ḱwéh₂- ("dog, canid"), evolving through Indo-Iranian branches to denote felids, underscoring the term's deep Indo-Aryan heritage amid the language's emergence from Prakrit substrates around 500 BCE. No credible evidence supports alternative Dravidian or autochthonous origins for the ethnonym, despite later admixtures in the lexicon; the lion-derivation aligns with epigraphic and literary consistency across Sanskrit, Pali, and Sinhala orthography.[5]Substratum Influences

The Proto-Sinhala language, derived from Indo-Aryan Prakrit varieties introduced by settlers around the 5th century BCE, incorporated substratum elements from indigenous languages of Sri Lanka, reflecting contact with pre-existing populations. These influences are evident in phonological, syntactic, and lexical features that deviate from typical Indo-Aryan patterns, such as the loss of aspirated stops and the development of prenasalized consonants, which align more closely with traits found in non-Indo-Aryan languages of the region.[16] A prominent hypothesis attributes these shifts to a South Dravidian substratum, possibly from early Tamil or related varieties spoken by southern Indian migrants or indigenous groups, given shared areal features like consistent left-branching syntax and SOV word order. This view is supported by genetic admixture studies indicating early Dravidian-like contributions to Sri Lankan populations, which correlate with linguistic convergence making Sinhala appear "deeply South Dravidian" despite its Indo-Aryan core. However, linguist James W. Gair cautions that direct causation via substratum is not conclusively proven, as some phonological innovations (e.g., retroflexion patterns) could arise from internal evolution or adstratum effects rather than wholesale replacement by a Dravidian-speaking substrate, and methodological challenges in identifying substrate languages persist due to limited historical records.[17][16] Alternative proposals invoke the Vedda language, classified as a linguistic isolate with Australoid affiliations, as a potential substratum source. Spoken by indigenous hunter-gatherers predating Indo-Aryan arrival, Vedda contributed unetymologized lexical items to Sinhala—estimated at several dozen words related to flora, fauna, and kinship that resist Indo-Aryan or Pali derivation—and possibly structural residues, though its contemporary form is heavily overlaid by Sinhala borrowings, complicating reconstruction. George van Driem notes that Vedda persists mainly as a fragmentary substrate in Vedda-influenced Sinhala dialects, underscoring bidirectional but asymmetric contact dynamics. Empirical verification remains limited by the near-extinction of pure Vedda speech by the 20th century, with ongoing debate over whether Dravidian or Vedda (or an undifferentiated indigenous layer) better explains the observed divergences.[18][16]Historical Development

Proto-Sinhala and Early Prakrit Features

Proto-Sinhala represents the transitional phase of the Sinhala language, emerging after the initial Prakrit forms introduced by Indo-Aryan settlers around the 6th century BCE and continuing into the 8th century CE. The earliest attestation appears in Brahmi-script inscriptions from the 3rd century BCE, such as cave dedications during the reign of King Devanampiya Tissa, which display a Prakrit closely aligned with Middle Indo-Aryan dialects but already showing insular adaptations.[19] These texts provide an unbroken inscriptional record, revealing a language derived from northern Indian Prakrits, likely influenced by migrations from regions speaking Magadhi-like varieties, though distinct from continental Prakrits in its rapid phonological simplification.[19] Key early Prakrit features in Proto-Sinhala include de-aspiration of stops (e.g., Sanskrit bhūmi evolving toward Sinhala bim 'earth'), simplification of geminate consonants, and retention of intervocalic voicing, consistent with broader Middle Indo-Aryan trends but evidenced in Sri Lankan edicts. Morphologically, it exhibited reduced case systems, favoring postpositions over synthetic endings, and verb conjugations with simplified tenses derived from Prakrit paradigms, as seen in inscriptional formulas like donor statements (deva 'king' forms yielding to local nominal patterns). Phonological hallmarks encompassed vowel harmony precursors and the emergence of prenasalization, distinguishing it from purer Prakrit while preserving core Indo-Aryan lexicon.[19] During this period, Proto-Sinhala developed innovative traits beyond standard Prakrit, such as umlaut-induced front vowels like /æ/ (e.g., from back vowel shifts in stressed syllables), marking divergence toward modern Sinhala phonology. These changes, documented in analyses of transitional inscriptions up to the 8th century CE, reflect endogenous evolution rather than direct continental parallels, with evidence from comparative linguistics highlighting Sinhala's isolation-driven conservatism in some consonants alongside substrate-driven vowel alterations.[20]Phonological Evolution

The phonological system of Sinhala diverged from its Indo-Aryan Prakrit antecedents around the 3rd century BCE, progressing through stages including Sinhala-Prakrit (3rd century BCE–4th century CE), Early Sinhala (4th–8th centuries CE), Middle Sinhala (8th–mid-13th centuries CE), and Modern Sinhala (mid-13th century CE–present), marked by progressive simplification and innovation in consonants and vowels.[21] Early changes eliminated geminate consonants by the 3rd century BCE, as in Pali *kamma yielding Sinhala *kam, reflecting a reduction in consonant length not seen uniformly in northern Indo-Aryan varieties.[22] Consonant shifts intensified in subsequent centuries: bilabial /p/ evolved to /v/ by the 1st–2nd centuries CE (e.g., Pali rūpa > Sinhala ruva), while /j/ shifted to /d/ from the 4th to 9th centuries CE (e.g., Pali vejja > Sinhala vedda).[22] Intervocalic /t/ developed into /l/ via an intermediate /d/ stage between the 6th and 10th centuries CE (e.g., Pali puttavi > Sinhala polova), and /c/ (as in affricates) transitioned to /s/ in the 8th–10th centuries CE (e.g., Pali gacchati > Sinhala gasa).[22] Sibilants underwent merger and weakening, with intervocalic Sanskrit /s/ becoming /h/ and ultimately vanishing by the 15th century CE (e.g., Sanskrit sūrya > Sinhala hīra > īra), culminating in the loss of the velar fricative /h/ by the end of the Middle Sinhala period.[22][21] Aspiration ceased to distinguish plosives, a hallmark divergence from Sanskrit and Pali where voiced and voiceless aspirates contrasted, resulting in a simpler stop inventory.[23] These evolutions also fostered innovations like phonemic prenasalized stops (e.g., /ᵐb/, /ⁿd/), which emerged as distinct from simple nasals or stops and persist in modern spoken forms, often analyzed as sequences but functioning phonologically as units in syllable structure.[24] Prenasalization likely arose from earlier nasal assimilation in clusters, contributing to Sinhala's avoidance of complex onsets beyond CV or prenasalized patterns. The vowel inventory stabilized into 14 phonemes by the modern era—seven qualities each short and long (/i iː/, /u uː/, /e eː/, /æ æː/, /ə əː/, /o oː/, and a high central /ɨ ɨː/ in some analyses)—with two extra-short or centralized qualities unique among Indo-Aryan languages, reflecting fronting and reduction processes like historical umlaut effects that linger morphologically but are no longer productive.[24][25][21] Overall, these shifts prioritized open syllables (favoring CV structures) and reduced markedness, influenced by areal contacts but rooted in internal Prakrit-like simplifications, yielding a phonology optimized for prosodic features like fixed initial stress rather than lexical tone.[24]Pre-Colonial Literature and Texts

The earliest attestations of the Sinhala language appear in rock inscriptions dating from the 3rd century BCE, primarily in Brahmi script, recording donations and royal decrees during the Anuradhapura period.[26] These texts, often brief and formulaic, demonstrate phonological features transitional between Prakrit and proto-Sinhala, such as vowel length retention and consonant shifts.[27] Over four thousand such inscriptions survive, providing evidence of the language's evolution through cave, slab, and pillar forms up to the 12th century CE.[28] Among the most significant pre-colonial literary artifacts are the Sigiriya graffiti, inscribed on the mirror wall of the Sigiriya rock fortress between the 6th and 14th centuries CE, with the majority from the 7th to 10th centuries.[29] Comprising over 1,800 entries in prose and verse, primarily in Sinhala with some Sanskrit and Tamil, these include poetic praises of the site's frescoes, romantic expressions, and visitor comments, marking the earliest extant examples of Sinhala poetry and offering insights into vernacular phonetics, syntax, and metrics.[30] The oldest surviving Sinhala prose work is the Dhampiya-Atuva-Getapadaya, compiled in the 9th century CE as a glossary and paraphrase aiding the study of the Pali Dhammapadatthakatha.[31] This text exemplifies early Sinhala literature's role in elucidating Buddhist scriptures, translating Pali terms into Sinhala synonyms and explanations to facilitate monastic education.[32] Another foundational text, the Siyabaslakara, attributed to King Sena I (r. 832–851 CE), is a treatise on poetics comprising verses on rhetorical ornaments (alankara) and prosody, representing the first known Sinhala work of literary criticism.[33] It draws from Sanskrit models like Dandin's Kavyadarsha while adapting them to Sinhala linguistic structures, influencing subsequent poetic composition in the Anuradhapura kingdom.[34] These works, preserved in palm-leaf manuscripts, underscore pre-colonial Sinhala literature's primary orientation toward Buddhist pedagogy and rhetorical theory rather than secular narrative forms.Colonial Influences (Portuguese, Dutch, British)

The Portuguese colonial presence in Sri Lanka, beginning with the capture of Colombo in 1518 and extending until their expulsion from most coastal areas by 1658, introduced numerous loanwords into Sinhala, primarily in domains such as trade, cuisine, religion, and everyday objects unfamiliar to local populations. Examples include mēsaya (table, from mesa), janēlaya (window, from janela), alavu (needle, from alfinete), and annāsi (pineapple, from ananas), which underwent phonological adaptation to fit Sinhala patterns, such as vowel shifts and consonant softening.[35] These borrowings filled lexical gaps caused by the introduction of European goods, administrative practices, and Catholic terminology, with over 200 documented Portuguese-derived terms persisting in modern Sinhala, reflecting the intensity of early contact in urban and coastal Sinhala-speaking communities.[36] Dutch rule from 1658 to 1796, following their conquest of Portuguese holdings, further enriched Sinhala vocabulary, particularly in legal, commercial, and household spheres, as the Dutch East India Company emphasized bureaucratic governance and trade. Key loanwords include vatūruva (water, from water), kōppaya (cup, from kop), kitalaya (kettle, from ketel), and administrative terms like ratum (rat, from raad, council), adapted through Sinhala compounding and nasalization.[36] Dutch missionaries, active from the late 17th century, contributed to Sinhala literature by translating Christian texts and producing printed materials, such as the first Sinhala-Dutch dictionary in 1737 and catechisms, which standardized certain orthographic and terminological usages while incorporating Dutch legal phrases into local discourse.[37] British colonization, initiated with the takeover of Dutch territories in 1796 and culminating in the Kandyan Kingdom's cession in 1815, exerted the most extensive lexical influence on Sinhala, driven by English-medium education, railway expansion from 1867, and bureaucratic reforms that permeated all social strata. English loanwords proliferated in technology, governance, and science, such as bīl (bill), bīro (bureau), gāranmentu (government), and tēlepon (telephone), often integrated as compounds or with Sinhala classifiers like -ek for singularity.[38] This era saw structural adaptations in spoken Sinhala, including code-switching in elite varieties and the nativization of approximately 1,000 English terms by the early 20th century, though grammatical influence remained minimal, preserving Sinhala's core Indo-Aryan syntax.[39] Overall, colonial borrowings constitute about 5-10% of contemporary Sinhala lexicon, with Portuguese terms evoking historical exoticism, Dutch ones tied to legacy institutions, and English dominating modern innovation.[36]Post-Independence Standardization

Following the Official Language Act No. 33 of 1956, which designated Sinhala as the sole official language of Ceylon (effective January 1, 1964), systematic efforts were undertaken to adapt and standardize the language for modern administrative, educational, and technical domains previously dominated by English.[40] This legislation necessitated the development of standardized terminology, glossaries, and stylistic conventions to facilitate its use in government, parliament, and higher education, marking a shift from colonial-era bilingualism to monolingual Sinhala proficiency requirements for public sector employment.[41] In October 1956, the Official Languages Department was established to spearhead vocabulary modernization, including the creation of Sinhala equivalents for scientific, legal, and administrative terms, alongside refinements to sentence structure and formal communication styles.[40] Concurrently, the Sinhala Department at the University of Ceylon (later University of Peradeniya) formed a "Swabasha office" under P.E.E. Fernando to coin neologisms, producing cyclostyled glossaries that were later adopted by the department; notable contributions included terms like "piripahaduwa" (parliament) by Aelian de Silva and economic concepts such as "mila niyaya" (supply and demand) by A.V. de S. Indraratne in 1961.[40] These initiatives expanded Sinhala's lexicon significantly, enabling its application in arts faculty instruction from 1960 and science faculties from 1968, while fostering a more formalized literary register for media and academia.[40] Educational reforms complemented these efforts, with mother-tongue instruction (swabasha) in Sinhala-medium schools formalized from 1949 but accelerated post-1956 to produce fluent administrators and scholars, reducing reliance on English translations.[40] By the 1970s, this standardization had yielded a robust, contemporary Sinhala capable of handling technical discourse, though it preserved the language's diglossic distinction between colloquial and literary forms without major orthographic overhauls.[40] The 1978 constitutional amendment, recognizing Tamil alongside Sinhala as official, introduced bilingual provisions but did not reverse the core standardization of Sinhala for national use.[41]Dialects and Variation

Regional Dialects

The Sinhala language features regional dialects shaped by geographical isolation and historical factors, with principal divisions into low-country varieties spoken along the coastal plains of the Western, Southern, and parts of the Sabaragamuwa provinces, and the up-country variety prevalent in the central highlands of the Central and Uva provinces. These distinctions arose from the political separation under the Kandyan Kingdom, which preserved up-country speech from coastal colonial influences until the British conquest in 1815. Low-country dialects exhibit subtle phonological shifts and lexical borrowings from Portuguese (16th–17th centuries), Dutch (17th–18th centuries), and English (19th century onward), reflecting extended trade and administrative contact.[10] Up-country dialects, centered in areas like Kandy and Matale, retain more conservative pronunciations, such as variations in verb forms; for instance, the infinitive "to do" (karanna in standard usage) undergoes phonetic modification in up-country speech, often with altered vowel quality or consonant aspiration. Northern dialects, exemplified by the Vanni variety in the Northern Province, contrast with western low-country forms in prosodic patterns and select consonants, as documented through comparative studies of local speech communities conducted in the mid-20th century.[42] These northern traits likely stem from partial isolation and substrate effects from pre-Sinhala populations, though empirical phonetic analyses confirm limited divergence overall. Dialectal differences manifest chiefly in accent, regional vocabulary (e.g., terms for local flora or terrain), and minor morphological alternations in verb conjugation or pronominal forms, but phonological inventories remain largely uniform across regions. Mutual intelligibility exceeds 95% between varieties, enabling fluid communication nationwide, as evidenced by sociolinguistic surveys of Sinhala speakers. Standardization efforts post-independence in 1948, via broadcasting and education, have further converged features, reducing perceptual gaps while preserving local identities in informal speech.[43]Diglossia and Registers

Sinhala displays diglossia, with a high variety (literary Sinhala) used primarily in writing, formal discourse, and literature, and a low variety (spoken or colloquial Sinhala) employed in informal everyday communication.[44] The high variety retains conservative grammatical structures, including subject-verb agreement and fuller inflectional paradigms, reflecting its roots in classical Prakrit-influenced forms.[45][46] In contrast, the low variety features reduced morphology, such as the absence of subject-verb agreement and simplified verb conjugations, alongside phonological shifts like vowel mergers and consonant lenition not present in the literary form.[45][46] Lexical differences further distinguish the varieties; for instance, formal expressions in literary Sinhala often draw from Sanskrit-derived terms, while spoken equivalents favor Dravidian-influenced or innovative native words, leading to non-equivalent vocabularies across domains like kinship and actions.[47] Within the spoken variety, sub-registers exist, including a formal spoken register for public speeches or broadcasting, which approximates literary syntax but retains colloquial phonology and lexicon, and a purely colloquial register for casual interaction.[44] Sociolinguistic analyses question the discreteness of these varieties, proposing instead a spectrum of registers where features mix continuously rather than bimodally, based on quantitative studies of speech variation showing gradual shifts correlated with formality and context.[48] In literary works like novels, authors typically employ literary Sinhala for narration and switch to spoken forms for dialogue, though contemporary youth discourse increasingly blends elements, challenging traditional boundaries.[49] This register variation extends to syntax, where literary forms use complex relative clauses with particles like da or nam, while spoken relies on simpler, non-inflected structures.[50]Standardization and Mutual Intelligibility

The standardization of Sinhala accelerated in the early 20th century through the Hela movement, led by Munidasa Cumaratunga during the 1930s and 1940s, which advocated purifying the language by prioritizing indigenous ("Hela") vocabulary and grammar over extensive Sanskrit and Pali loanwords that had dominated classical literature.[51] This effort contrasted with prior pirivena (monastic school) traditions that modeled Sinhala grammar on Pali or Sanskrit frameworks, influencing modern literary Sinhala by promoting a more native-oriented register for prose and poetry.[51] Post-independence in 1948, the Official Language Act of 1956 established Sinhala as the sole official language, displacing English in government administration and secondary education while initiating systematic standardization for public domains.[41] This policy drove the codification of norms in orthography, terminology, and usage through state institutions, broadcasting (e.g., via Radio Ceylon), and school curricula, fostering a unified standard spoken form derived from colloquial varieties while preserving a diglossic divide with literary Sinhala.[52] By the 1970s, these measures had entrenched a prestige dialect approximating central-southern colloquial Sinhala as the basis for media and education, though full orthographic reforms remained debated due to script complexities.[53] Sinhala dialects, including coastal (low-country), highland (up-country), and north-central variants, maintain high mutual intelligibility, with phonological, lexical, and minor grammatical divergences insufficient to create significant barriers to comprehension across regions.[42] Academic analyses describe these differences as gradual rather than discrete, forming a dialect continuum where adjacent varieties are fully intelligible, and even distant ones allow understanding without formal training, unlike sharper divides in some Indo-Aryan languages.[42] This cohesion supports national standardization, as speakers readily adapt to the prestige form in formal contexts, though peripheral dialects like those with Vedda substrate show archaic features that may require minor accommodation.[54]Writing System

Script Structure and Characters

The Sinhala script functions as an abugida, where consonant glyphs serve as the core units, each incorporating an inherent vowel sound—typically transcribed as /a/ and realized phonetically as [ə] or [ɐ]—that is modified or eliminated via attached diacritics or a vowel-killing mark.[55] This structure derives from Brahmic traditions, enabling syllabic representation through consonant-vowel combinations written left-to-right.[55] The script encompasses 18 independent vowel symbols (swara or uyanna) for syllable-initial positions and 17 dependent vowel signs (pilla) that attach to preceding consonants to specify alternative vowels, such as long or diphthongal forms.[56] Consonant symbols (wyangjana) total 41, categorized by articulatory features into five primary varga groups—velar (e.g., ක k, ග g), palatal (ච c, ජ j), retroflex (ට ṭ, ඩ ḍ), dental (ත t, ද d), and labial (ප p, බ b)—supplemented by nasals, semivowels (ය y, ර r, ල l, ව v), sibilants (ෂ ṣ, ස s, හ h), and specialized letters for aspiration or foreign sounds.[56] Two additional semi-consonant-like symbols address specific phonetic needs, yielding a core inventory of around 61 graphemes before modifiers.[57] Clusters form sparingly in native Sinhala, primarily through the virama (hal kirīma, ්) to suppress inherent vowels between consonants, often resulting in linear sequences rather than stacked ligatures common in other Indic scripts; prenasalized stops, prevalent in the phonology, appear as nasal-plus-obstruent pairs without explicit liaison marks.[55] Distinctive orthographic conventions include the repaya diacritic—a compact superscript ්ර—for word-final or intervocalic /r/, streamlining cursive flow, and occasional conjunct reductions for readability in compounds.[55] These elements accommodate the language's 40-odd phonemes while preserving historical layers from Prakrit and Sanskrit influences.[57]Historical Evolution and Reforms

The Sinhala script traces its origins to the Brahmi script, with the earliest known inscriptions appearing in Sri Lanka around the 3rd century BCE, primarily in cave and rock markings.[58] These early forms derived from Southern Brahmi, a variant used in the Indian subcontinent, and evolved gradually from the 1st century CE onward, incorporating distinct rounded shapes influenced by regional adaptations.[4] By the Sigiriya period in the 5th century CE, the script had developed new vowel letters, such as those for æ (ඇ) and œ (ඕ), reflecting phonological changes in the Sinhala language.[4] Further evolution occurred between the 6th and 10th centuries CE, as documented in inscriptional evidence, where the script transitioned toward more cursive and abbreviated forms suited to palm-leaf manuscripts.[59] Pallava influences from South India, spanning the 4th to 9th centuries CE, contributed to refinements in consonant shapes and ligature formations, blending local innovations with external stylistic elements.[60] This period solidified the abugida structure, with inherent vowels and diacritics, distinguishing it from parent Brahmi while maintaining compatibility for rendering Pali texts in Buddhist contexts.[61] Modern reforms began in the colonial era with the introduction of printing presses in the 18th century, standardizing glyph forms for typographic reproduction, as seen in the first printed Sinhala book from 1737.[62] Post-independence efforts in the mid-20th century included orthographic simplification proposals, such as a 1950 initiative by the Dinamina newspaper to reduce character complexity and align spelling more closely with phonetics.[63] Digital standardization accelerated in the late 20th century, with the first comprehensive Sinhala character set encoding proposed for public comment in 1990 to facilitate computing and Unicode integration, addressing ambiguities in legacy representations.[64] These reforms prioritized practical usability over radical redesign, preserving the script's historical integrity amid technological demands.[65]Orthographic Challenges

The Sinhala abugida script presents orthographic challenges due to its intricate structure, where consonants carry an inherent vowel (/ə/) that must be suppressed or modified via diacritics (pilla), leading to highly variable glyph shapes that obscure syllable boundaries and increase visual confusion for learners and automated systems.[24] This complexity is compounded by conjunct forms for consonant clusters, which often stack vertically or horizontally, resulting in segmentation ambiguities during handwriting recognition, as not all 56 graphemes are uniformly used in modern writing.[66] A primary challenge stems from diglossia, where literary orthography preserves Pali and Sanskrit-derived etymologies, diverging from colloquial pronunciation and fostering spelling inconsistencies; for instance, common errors involve mismatched vowel lengths (e.g., short vs. long /a/) or assimilation of prenasalized consonants, as writers apply spoken forms to formal texts.[67] [68] Such morphophonemic discrepancies produce homophonous words with multiple valid spellings tied to semantic or historical distinctions, exacerbating real-word errors that evade detection since the misspelled form exists in the lexicon.[69] In digital environments, orthographic fidelity is undermined by incomplete Unicode support for certain vowel modifiers and conjuncts, alongside inconsistent font rendering across platforms, despite the adoption of standards like SLASCII in 1996 and SLS 1134 in 2004 for input methods.[70] These issues manifest in encoding mismatches during typing, where ad-hoc Roman-to-Sinhala transliterations introduce further ambiguities, and limited documentation hinders developer compliance.[71] Proposed reforms, such as script simplification, have gained traction but face resistance due to cultural attachment to traditional forms.[72]Phonology

Consonant Inventory

The Sinhala consonant inventory comprises 26 phonemes, fewer than in many other Indo-Aryan languages.[24] [73] This system includes contrasts between dental and retroflex obstruents across stops and sibilants, alongside nasals at those places of articulation.[24] A distinctive feature is the series of four prenasalized voiced stops—/ᵐb/, /ⁿd/, /ɳɖ/, and /ᵑg/—which are rare cross-linguistically and phonetically realized with shorter nasal portions than corresponding full nasals.[24] [73] The inventory lacks aspirated stops, unlike many Indo-Aryan counterparts, and includes labiodental fricatives /f/ and approximant /ʋ/, which may reflect influences from contact languages.[24] Palatal affricates /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/ provide postalveolar articulation, while /r/ is typically a trill and /l/ a lateral approximant, both alveolar.[24]| Bilabial | Labiodental | Dental | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɳ | ŋ | |||

| Plosive | p b | t d | ʈ ɖ | k ɡ | |||

| Prenas. plos. | ᵐb | ⁿd | ɳɖ | ᵑɡ | |||

| Affric. | t͡ʃ d͡ʒ | ||||||

| Fricative | f | s | ʂ | h | |||

| Approx./Trill/Lateral | ʋ | l r | j |

Vowel System

The vowel system of Sinhala comprises 14 monophthongs, formed by a distinction in length for each of seven basic vowel qualities.[75] These qualities include close front unrounded /i/, close back rounded /u/, close-mid front unrounded /e/, close-mid back rounded /o/, open-mid front unrounded /ɛ/, open-mid back rounded /ɔ/, and open central unrounded /a/, with corresponding long variants /iː/, /uː/, /eː/, /oː/, /ɛː/, /ɔː/, and /aː/.[76] Vowel length is phonemically contrastive, affecting word meaning; for instance, short /a/ contrasts with long /aː/ in minimal pairs such as hada ('vomit') versus hāda ('tongue').[76] Back vowels (/u/, /o/, /ɔ/, and their long counterparts) are rounded, while all others are unrounded.[76] A central schwa-like vowel [ə] occurs as a non-phonemic epenthetic sound in certain consonant clusters but does not form part of the core inventory.[76] Sinhala also features diphthongs, primarily /ai/ and /au/, which arise in spoken forms and contribute to the language's phonetic richness.[76] Some analyses identify additional diphthongs such as /iu/, /eu/, /ou/, though their phonemic status varies across dialects and registers.[24] Nasalized vowels, including /ã/, /ãː/, /æ̃/, and /æ̃ː/, appear in specific contexts influenced by neighboring nasals but are not considered primary phonemes in standard inventories.[77]Phonotactics and Prosody

Sinhala phonotactics permit simple syllable structures in native (Nishpanna) vocabulary, limited to (C)V(C), encompassing open syllables (V, CV) and closed syllables (VC, CVC).[78] Borrowed terms from Sanskrit or Pali (Thathsama/Thadbhava) allow more complex onsets and codas, up to three consonants, as in (C)(C)(C)V(C)(C)(C), though clusters are governed by sonority hierarchy and specific rules favoring glides like /r/ or /y/ in medial positions.[24] [78] Diphthongs occur with a high second vowel (e.g., /ai/, /au/, /oi/), and vowel nasalization is rare, primarily following prenasalized stops, as in /kũːb̃i/ 'ants'.[24] Syllabification follows iterative rules prioritizing maximal onset: for sequences like xVCV, the boundary falls after the first vowel (xV)(CV); for xVCCV, after the coda (xVC)(CV); and for xVV, between vowels (xV)(V).[78] In complex clusters, boundaries respect glide attachments (e.g., xVCC[/r/ or /y/]V as (xVC)(C[/r/ or /y/]V)) or stop sequences (xV[C-Stop][C-Stop]CV as (xVC)(CCV)), with accuracy exceeding 99% in algorithmic tests on large corpora.[78] Ambisyllabicity arises in some forms, allowing multiple parses, such as /sampreːkʂənə/ as /sam.preːkʂə.nə/ or /samp.reːkʂə.nə/.[24] Prosodically, Sinhala exhibits weak or absent lexical stress, with no contrastive or unpredictable emphasis; fixed initial-syllable prominence occurs alongside stress on long vowels, as in /haːmuduruvoː/ 'monk'.[24] [79] Phrasal stress favors non-verbal elements, while focus is marked through prosodic rephrasing into separate intonational phrases with boundary tones (low L at left edge, high H at right), rather than pitch accents.[79] [24] Intonation patterns include falling contours for declarative finality (e.g., /amma pansal gihɪlla/ 'Mother has gone'), rising for questions or surprise, and level for continuation or non-finiteness.[24] Pitch contours distinguish finite verbs (falling) from non-finite (level), and wh-in-situ questions employ boundary tones for licensing, with particles like -də signaling contrastive focus contextually.[24] [79] Clause-final vowel shifts (e.g., -a to -e) interact with these tones to convey information structure.[79]Grammar

Nominal Morphology

Sinhala nouns inflect primarily for animacy, number, case, and definiteness, with no grammatical gender distinctions requiring agreement.[80] Nouns are classified into animate (rational, including humans and higher animals) and inanimate (irrational, covering objects, plants, and lower animals) categories, which condition differential marking patterns.[80] This binary animacy split influences plural formation and case inventory, reflecting a departure from fusional Indo-Aryan patterns toward more agglutinative or analytic structures in colloquial usage.[81] Number is marked by singular and plural forms, with stark contrasts between animate and inanimate nouns. Animate plurals typically append suffixes such as -o, -u, or -valu to the stem, as in singular gōviyā "farmer" yielding plural gōviyō or gōviyōvalu.[82] Inanimate plurals, however, employ subtractive morphology, deriving the singular from a base form by vowel addition or extension, resulting in shorter plural forms that counter the cross-linguistic iconicity principle of longer plurals for multiplicity.[82] [83] For instance, inanimate stems like pot "book" appear in plural without overt addition, while singulars extend to pothə; this system divides inanimates into subclasses based on stem phonology, with some showing zero plural marking.[82] Singular indefinites may add -ak (inanimate or masculine-like) or -ek (feminine-like animate), preceding case markers.[5] The case system varies by animacy and register, with spoken Sinhala using four cases for inanimates—nominative (unmarked), dative (-ta), genitive (-ge), and instrumental (-in)—and six for animates, incorporating accusative (-wa) and ablative (-gənə) alongside the shared forms.[80] Animate direct objects exhibit differential marking, optionally using accusative -wa or dative-like -ta based on definiteness and discourse prominence, while inanimates rely on word order or dative -ta for patient roles.[81] [84] Literary Sinhala expands to eight cases, including locative (-ət), but colloquial forms favor postpositional clitics over strict declensional endings, with stems grouped into a-, i-, u-, and consonant-ending classes for vowel harmony in suffixes.[85] Definiteness is obligatorily marked in singulars via the suffix -ə (a schwa-like vowel), distinguishing definite from indefinite forms; for example, potə denotes "the book," while bare stems or -ak signal indefiniteness.[86] Plural definites lack a dedicated marker, relying on context or number alone, and interact with case such that definite singulars precede markers like -ge.[80] This morphological encoding of definiteness is atypical among Indo-Aryan languages and aligns Sinhala closer to Dravidian traits in nominal marking.[86]| Case | Animate Marker | Inanimate Marker | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | ∅ | ∅ | Subject or unmarked |

| Accusative | -wa (optional) | ∅ or -ta | Direct object (animate-specific) |

| Dative | -ta | -ta | Indirect object, purpose |

| Genitive | -ge | -ge | Possession |

| Instrumental | -in / -ən | -in | Means, accompaniment |

| Ablative | -gənə | (merged with genitive) | Source, separation |

Verbal Morphology

Sinhala verbs display a complex morphology characterized by stem alternations and suffixation to encode tense, aspect, and mood, with finite forms primarily distinguishing past from non-past tenses. A single verb stem can generate more than 250 conjugated forms through combinations of these elements, reflecting the language's Indo-Aryan heritage adapted to analytic tendencies in spoken usage.[87] Verbs are classified into conjugation classes based on stem vowel patterns, typically three for regular verbs: those ending in -a- (class 1), -i- (class 2), and -e- (class 3), which determine inflectional behavior across tenses.[45] Irregular verbs, including strong verbs with ablaut-like changes, deviate from these patterns, while causatives form a separate class via prefixation or stem modification.[88] The verbal paradigm relies on four primary stem shapes—A (present active), P (past), N (non-finite or nominal), and V (infinitive)—which serve as bases for further inflection, though spoken Sinhala often simplifies finite forms to invariant shapes without explicit person, number, or gender marking.[21] Non-past tense (encompassing present and future) forms via the stem plus suffixes like -nəwə or -nawə, as in karənəwə ("does/makes") from the root kara-. Past tense involves stem changes or additions like -pu or -ə, yielding karəpu ("did/made"), with class-specific variations such as vowel harmony or consonant insertion in class 2 and 3 verbs.[45] Literary Sinhala retains pronominal suffixes for person in past tense (e.g., -ən for 1st singular), but colloquial forms omit them, relying on syntactic context or auxiliaries.[80] Aspectual distinctions, such as continuous or habitual, are largely periphrastic, employing conjunctive participles (stem + -dʑi or -nəwə) combined with auxiliaries like irənnə ("be") or enə ("come") for progressive senses, e.g., karənəwə irənnə ("is doing").[89] Moods include imperative (bare stem or stem + -wə), conditional (stem + -dʑə or periphrastic with -lə), and optative forms via suffixes like -m or auxiliaries, with past conditionals adding aspectual layers.[45] Passive voice is expressed periphrastically using the verb karənəwə ("do") with nominalized objects, while causatives derive from involitive stems or prefixes like pa-/-wa-, distinguishing volitive (agentive) from involitive (stative or non-voluntary) pairs inherent to many roots.[80] Non-finite forms include infinitives (stem + -nə or -nna), gerunds (stem + -dəwə), and verbal nouns, facilitating complex clauses without finite marking.[21] Modern analyses confirm two morphological tenses—past and non-past—contrasting traditional grammars' three, with aspect and mood integrated via these stems rather than independent categories.[90]Syntax and Word Order