Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

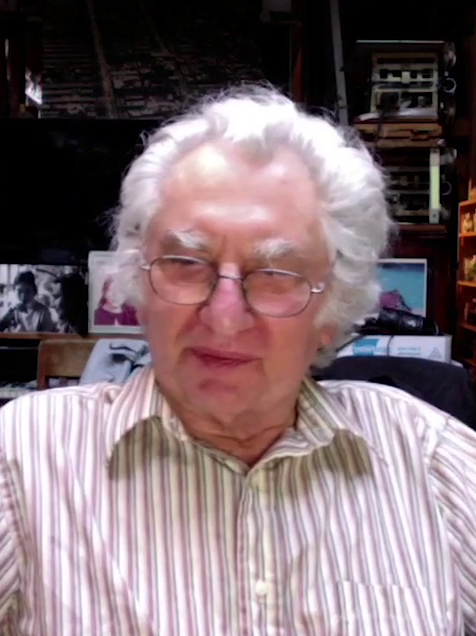

Ken Jacobs

View on WikipediaKenneth Martin Jacobs (May 25, 1933 – October 5, 2025) was an American experimental filmmaker.[2][3] His style often involved the use of found footage which he edited and manipulated. He also directed films using his own footage.

Key Information

Life and career

[edit]Ken Jacobs was born in Brooklyn on May 25, 1933.[1][4][5] He directed Blonde Cobra in 1963. This short film stars Jack Smith who directed his own Flaming Creatures the same year. In 1969 he directed Tom, Tom, the Piper's Son (1969, USA), in which he took the original 1905 short film and manipulated the footage to recontextualize it. This is considered an important first example of deconstruction in film. The film was admitted to the National Film Registry in 2007. His Star Spangled to Death (2004, USA) is a nearly seven-hour film consisting largely of found footage.[6] Jacobs began compiling the archival footage in 1957 and the film took 47 years to complete.[7]

Jacobs taught at the Cinema Department at Harpur College at Binghamton University from 1969 to 2002.[8] His son Azazel Jacobs is also a filmmaker.[9]

In the 1990s, Jacobs began working with John Zorn and experimented with a stroboscopic effect, digital video, and 3D effects. Jacobs died from kidney failure in Manhattan, New York, on October 5, 2025, at the age of 92.[10] His wife and frequent collaborator, Flo, died in June of the same year.[10]

Selected filmography

[edit]- Little Stabs at Happiness (1960), 14:57 min, color, sound, 16 mm film on video.[11]

- Blonde Cobra (1963), 33 min, color and b&w, sound, 16 mm film on video.[11]

- Window (1964)[12]

- Lisa and Joey in Connecticut (1965), 21:59 min, color, silent, Super 8mm film on video.[11]

- Tom, Tom, The Piper's Son (1969), 133 min, color and b&w.[11]

- Perfect Film (1986)

- Opening the Nineteenth Century: 1896 (1991)

- The Georgetown Loop (1996), 11 min, b&w, silent.[11]

- Circling Zero: We See Absence (2002), 114:38 min, color, sound.[13][14]

- Star Spangled to Death (2004), 440 min, b&w and color, sound, DVD. Clip collection began in 1956.[11]

- Nymph (2007), 2 min, color, silent.[11]

- Gift of Fire: Nineteen (Obscure) Frames that Changed the World (2007), 27:30 min, anaglyph 3-D color, surround sound.[11]

- The Scenic Route (2008), 25 min, color and b&w, sound.[11]

- 60 Seconds of Solitude in Year Zero, first segment.[15]

- Seeking the Monkey King (2011), 39:42 min, color, 5.1 surround sound, HD video.[11]

- Joys of Waiting for the Broadway Bus (2013), 4–part series, enhanced 3D film digital slides.[16]

- A Primer in Sky Socialism (2013), color 3D film.[17][18]

Awards and accolades

[edit]He was a recipient of the 1994 American Film Institute's Maya Deren Award.[9] In 2012 he received a Creative Capital Moving Image grant award.[19] In 2014 he was named a United States Artists (USA) Fellow.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Malin, Sean (October 6, 2025). "Ken Jacobs, Visionary Experimental Filmmaker, Is Dead at 92". The New York Times. Retrieved October 6, 2025.

- ^ ""Conversations With History: Ken Jacobs", interview at UC Berkeley". Archived from the original on 2009-04-29. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ^ Review of book Optic Antics

- ^ "Light Cone – Ken Jacobs".

- ^ "Ken Jacobs". Electronic Arts Intermix. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 20, 2015.

- ^ Knipfel, Jim (September 2006). ""Movies are All People Know" An Interview With Ken Jacobs". The Brooklyn Rail.

- ^ Pagán, A. (2022). Emotional Materials / Personal Processes. Six Interviews with Experimental Filmmakers (StereoEditions), p. 65.

- ^ Bunnell, Irene. "Ken Jacobs: Educator, innovator, filmmaker". Binghamton University: Department of Cinema at Harpur College. Binghamton University. Archived from the original on June 11, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- ^ a b "October 17/18 – Ken Jacobs and Azazel Jacobs – Two Different Shows". Los Angeles Film Forum. October 12, 2009. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- ^ a b Saperstein, Pat (October 6, 2025). "Ken Jacobs, Pioneering Experimental Filmmaker, Dies at 92". Variety. Retrieved October 6, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Ken Jacobs-Biography". Electronic Arts Intermix. EAI. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- ^ Ken Jacobs-IFFR

- ^ Sicinski, Michael (May 11, 2015). "3D in the 21st Century. Flash Forward: Four 3D Works by Ken Jacobs". Notebook Digital Magazine.

- ^ Ken Jacobs’ documentary “Circling Zero : We See Absence”, 2002, VHS, USA can be found in the Experimental Television Center and its Repository in the Rose Goldsen Archive of New Media Art, Cornell University Library.

- ^ "60 Seconds of Solitude in Year Zero", Wikipedia, 2025-05-28, retrieved 2025-06-08

- ^ "Almost 80, He Continues the Ruckus". New York Times. 18 May 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ New Silent Cinema. Routledge. 2015. ISBN 9781317819448.

- ^ "A Primer in Sky Socialism". EMPAC. 5 October 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ "Joys of Waiting for the Broadway Bus / A Primer In Sky Socialism". Creative Capital. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ "United States Artists » Ken Jacobs". Retrieved 2023-02-27.