Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

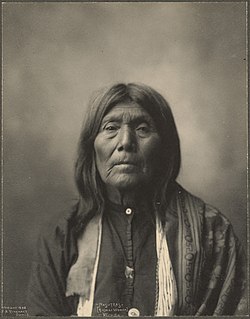

Kichai people

View on WikipediaThe Kichai tribe (also Keechi or Kitsai) was a Native American Southern Plains tribe that lived in Texas,[2] Louisiana, and Oklahoma. Their name for themselves was K'itaish.

Key Information

History

[edit]The Kichai were most closely related to the Pawnee.[1] French explorers encountered them on the Red River in Louisiana in 1701.[3] By 1772, they were primarily settled around the east of the Trinity River, near present-day Palestine, Texas.[4] After forced relocation, they came to share portions of southern and southwestern Oklahoma with the Wichita and with the Muscogee Creek Nation.[1]

The Kichai were part of the complex, shifting political alliances of the South Plains. Early Europeans identified them as enemies of the Caddo.[5] In 1712, they fought the Hainai along the Trinity River;[3] however, they were allied with other member tribes of the Caddoan Confederacy and intermarried with the Kadohadacho during this time.[3]

On November 10, 1837, the Texas Rangers fought the Kichai in the Battle of Stone Houses. The Kichai were victorious, despite losing their leader in the first attack.[6]

20th and 21st centuries

[edit]Caddo-Wichita-Delaware lands were broken up into individual allotments at the beginning of the 20th century. Kichai people's allotted lands were mainly in Caddo County, Oklahoma. Forty-seven full-blood Kichai lived in Oklahoma in 1950. There were only four at the end of the 20th century.[1]

The Kichai are not a distinct federally recognized tribe, but they are instead enrolled in the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes. These tribes live mostly in Southwestern Oklahoma, particularly in Caddo County, to which they were forcibly relocated by the United States Government in the 19th century.

Language

[edit]The Kichai language is a member of the Caddoan language family, along with Arikara, Pawnee, and Wichita.[7]

Kai Kai, a Kichai woman from Anadarko, Oklahoma, was the last known fluent speaker of the Kichai language. She collaborated with Dr. Alexander Lesser to record and document the language.[8]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Sanchez, Joe. "Kichai". Oklahoma Historical Society. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ Sturtevant, 6

- ^ a b c Kichai Indian History. Access Genealogy. (retrieved 6 Sept 2009)

- ^ Krieger, Margery H. Kitchai Indians. The Handbook of Texas Online. (retrieved 6 Sept 2009)

- ^ Sturtevant, 618

- ^ Loftin, Jack O. Stone Houses, Battle of. The Handbook of Texas Online. (retrieved 6 Sept 2009)

- ^ Sturtevant, 616

- ^ Science: Last of the Kitsai. Time. 27 June 1932 (retrieved 6 Sept 2009)

References

[edit]- Sturtevant, William C., general editor and Raymond D. Fogelson, volume editor. Handbook of North American Indians: Southeast. Volume 14. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2004. ISBN 0-16-072300-0.

,_Wichita.jpg/250px-Nasuteas_(Kichai_Woman),_Wichita.jpg)

,_Wichita.jpg)