Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Parapharyngeal space

View on Wikipedia| Parapharyngeal space | |

|---|---|

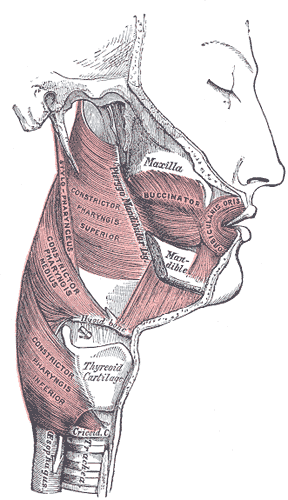

Lateral head anatomy detail | |

Muscles of the pharynx and cheek. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | spatium lateropharyngeum, spatium pharyngeum laterale, spatium parapharyngeum |

| MeSH | D000080886 |

| TA98 | A05.3.01.117 |

| TA2 | 2883 |

| FMA | 84967 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The parapharyngeal space (also termed the lateral pharyngeal space), is a potential space in the head and the neck. It has clinical importance in otolaryngology due to parapharyngeal space tumours and parapharyngeal abscess developing in this area. It is also a key anatomic landmark for localizing disease processes in the surrounding spaces of the neck; the direction of its displacement indirectly reflects the site of origin for masses or infection in adjacent areas, and consequently their appropriate differential diagnosis.[1]

Anatomical boundaries

[edit]The parapharyngeal space is shaped like an inverted pyramid. Lateral and inferior to the parapharyngeal space is the carotid sheath, containing the internal carotid artery and cranial nerves IX, X and XI. Behind both the parapharyngeal space and carotid space lies the retropharyngeal space, and deep to this a potential space known as the danger space. The danger space serves as an important pathway for complicated infections of the posterior pharynx to enter the chest and spinal column. Anterior to the parapharyngeal space is the masticator space which contains the lower dental row, muscles of mastication, the inferior alveolar nerve as well as branches of cranial nerve V. Lateral to the parapharyngeal space lies the parotid space, which contains the parotid gland, the external carotid artery and cranial nerve VII.[1] Although initial evaluation is typically by physical exam and endoscopy, follow up with CT and MRI usually is needed if surgical intervention is planned.[2]

Bony anatomy around the space includes the skull base superiorly, and the greater cornu (or greater horns) of the hyoid bone the apex, inferiorly. The superior aspect is the base of skull, namely the sphenoid and temporal bones. This area includes the jugular and hypoglossal canal and the foramen lacerum (through which the internal carotid artery passes superiorly across).

The medial aspect is made up of the pharynx. Anteriorly it is bordered by the pterygomandibular raphe. Posteriorly it is bordered by carotid sheath posteriolaterally and the retropharyngeal space posteriomedially. The lateral aspect is more involved, and is bordered by the ramus of the mandible, the deep lobe of the parotid gland, the medial pterygoid muscle, and below the level of the mandible, the lateral aspect is bordered by the fascia of the posterior belly of digastric muscle. These anatomical boundaries make it continuous with the retropharyngeal space. It also communicates with other cervical and cranial fascial spaces, as well as the mediastinum.

Divisions

[edit]The parapharyngeal space is divided into 2 parts by the fascial condensation called the aponeurosis of Zuckerkandl and Testut (stylopharyngeal fascia - see diagram),[3] joining the styloid process to the tensor veli palatini. These two compartments are named the pre-styloid and post-styloid (retrostyloid)[4] compartments or spaces. However, some classification schemes call the pre-styloid compartment the parapharyngeal space and the post-styloid compartment the carotid space,[5] which can be a source of confusion.

Contents

[edit]It includes the maxillary artery and ascending pharyngeal artery.[6]

- Glossopharyngeal nerve (IX)

- Vagus nerve (X) together with

- Internal carotid artery

- Internal jugular vein in the carotid sheath

- Accessory nerve (XI)

- Hypoglossal (XII)

- Sympathetic trunk and superior cervical ganglion of the trunk

- Ascending pharyngeal artery

- Deep cervical lymph nodes

Clinical significance

[edit]First bite syndrome is a rare complication of a surgery involving the parapharyngeal space, especially removal of the deep lobe of the parotid gland. It is characterized by facial pain after the first bite of each meal, and is thought to be caused by autonomic dysfunction of salivary myoepithelial cells.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Unger, J. M.; Chintapalli, K. N. (1983). "Computed tomography of the parapharyngeal space". Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 7 (4): 605–9. doi:10.1097/00004728-198308000-00006. PMID 6863661.

- ^ Mödder, U; Lenz, M; Steinbrich, W (1987). "MRI of facial skeleton and parapharyngeal space". European Journal of Radiology. 7 (1): 6–10. PMID 3830193.

- ^ Hermans 2006, p. 165

- ^ Fakhry 2016.

- ^ Jeremy Jones. "Carotid space". radiopaedia.org.

- ^ "EURORAD - Radiologic Teaching Files". eurorad.org.

Bibliography

[edit]- Hermans, Robert (2006). Head and Neck Cancer Imaging. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-22027-5.

- Fakhry, Nicolas (25 July 2016). "A proposal for a level for parapharyngeal extension of parotid gland". European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 273 (10): 3455. doi:10.1007/s00405-016-4226-8. PMID 27455864.