Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

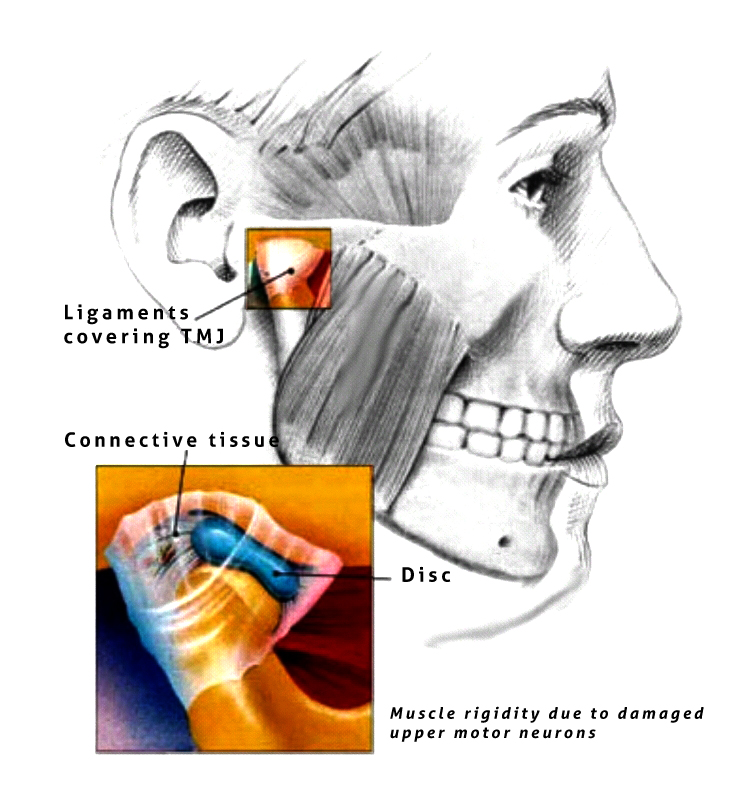

Trismus

View on Wikipedia| Trismus | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Lockjaw |

| |

| Trismus caused due to muscle rigidity. Diagram of jaw muscles are shown here. | |

Trismus is a condition of restricted opening of the mouth.[1][2] The term was initially used in the setting of tetanus.[2] Trismus may be caused by spasm of the muscles of mastication or a variety of other causes.[3] Temporary trismus occurs much more frequently than permanent trismus.[4] It is known to interfere with eating, speaking, and maintaining proper oral hygiene. This interference, specifically with an inability to swallow properly, results in an increased risk of aspiration. In some instances, trismus presents with altered facial appearance. The condition may be distressing and painful. Examination and treatments requiring access to the oral cavity can be limited, or in some cases impossible, due to the nature of the condition itself.

Definition

[edit]Trismus is defined as painful restriction in opening the mouth due to a muscle spasm,[5] however it can also refer to limited mouth opening of any cause.[6] Another definition of trismus is simply a limitation of movement.[4] Historically and commonly, the term lockjaw was sometimes used as a synonym for both trismus[2] and tetanus.[7]

Normal mouth-opening ranges from 35 to 45 mm.[6] Males usually have slightly greater mouth opening than females. (40–60 mm, average of 50 mm). The normal lateral movement is 8–12 mm,[8] and normal protrusive movement is approximately 10 mm.[medical citation needed] Some have distinguished mild trismus as 20–30 mm interincisal opening, moderate as 10–20 mm and severe as less than 10 mm.[9]

Trismus is derived from the Greek word trigmos/trismos meaning "a scream; a grinding, rasping or gnashing".[10]

Differential diagnosis

[edit]Traditionally causes of trismus are divided into intra-articular (factors within the temporomandibular joint [TMJ]) and extra-articular (factors outside the joint, see table).[4]

| Commonly listed causes of trismus |

|---|

|

Intra-articular:

Extra-articular:

|

Joint problems

[edit]Ankylosis

[edit]- True bony ankylosis: can result from trauma to chin, infections and from prolonged immobilization following condylar fracture

- Treatment – several surgical procedures are used to treat bony ankylosis, e.g.: Gap arthroplasty using interpositional materials between the cut segments.

- Fibrous ankylosis: usually results due to trauma and infection

- Treatment – trismus appliances in conjunction with physical therapy.

Arthritis synovitis

[edit]Meniscus pathology

[edit]Extra-articular causes

[edit]Infection

[edit]- Odontogenic- Pulpal

- Periodontal

- Pericoronal

- Non-odontogenic- Peritonsillar abscess

- Tetanus

- Meningitis

- Brain abscess

- Parotid abscess

- The hallmark of a masticatory space infection is trismus or infection in anterior compartment of lateral pharyngeal space results in trismus. If these infections are unchecked, can spread to various facial spaces of the head and neck and lead to serious complications such as cervical cellulitis or mediastinitis.

- Treatment: Elimination of etiologic agent along with antibiotic coverage

- Trismus or lock jaw due to masseter muscle spasm, can be a primary presenting symptom in tetanus, Caused by Clostridium tetani, where tetanospasmin (toxin) is responsible for muscle spasms.

- Prevention: primary immunization (DPT)

Dental treatment

[edit]- Dental trismus is defined by difficulty in opening the jaw. It is a temporary condition that usually lasts no more than two weeks. Dental trismus is caused by an injury to the masticatory muscles, such as opening the jaw for an extended period of time or having a needle pass through a muscle. Typical dental anesthesia for the lower jaw involves inserting a needle into or through a muscle. In these cases it is usually the medial pterygoid or the buccinator muscles.

- Oral surgery procedures, as in the extraction of lower molar teeth, may cause trismus as a result either of inflammation to the muscles of mastication or direct trauma to the TMJ.

- Barbing of needles at the time of injection followed by tissue damage on withdrawal of the barbed needle causes post-injection persistent paresthesia, trismus and paresis.

- Treatment: in acute phase:

- Heat therapy

- Analgesics

- A soft diet

- Muscle relaxants (if necessary)

- Note: When acute phase is over the patient should be advised to initiate physiotherapy for opening and closing mouth.

- Treatment: in acute phase:

Trauma

[edit]Fractures, particularly those of the mandible and fractures of zygomatic arch and zygomatic arch complex, accidental incorporation of foreign bodies due to external traumatic injury. Treatment: fracture reduction, removal of foreign bodies with antibiotic coverage[citation needed]

TMJ disorders

[edit]- Extra-capsular disorders – Myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome

- Intra-capsular problems – Disc displacement, arthritis, fibrosis, etc.

- Acute closed locked conditions – displaced meniscus

Tumors and oral care

[edit]Rarely, trismus is a symptom of nasopharyngeal or infratemporal tumors/ fibrosis of temporalis tendon, when patient has limited mouth opening, always premalignant conditions like oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF) should also be considered in differential diagnosis.

Drug therapy

[edit]Succinyl choline, phenothiazines and tricyclic antidepressants causes trismus as a secondary effect. Trismus can be seen as an extra-pyramidal side-effect of metoclopromide, phenothiazines and other medications.

Radiotherapy and chemotherapy

[edit]- Complications of radiotherapy:

- Osteoradionecrosis may result in pain, trismus, suppuration and occasionally a foul smelling wound.

- When muscles of mastication are within the field of radiation, it leads to fibrosis and result in decreased mouth opening.

- Complications of Chemotherapy:

- Oral mucosal cells have high growth rate and are susceptible to the toxic effects of chemotherapy, which lead to stomatitis.

Congenital and developmental causes

[edit]- Hypertrophy of coronoid process causes interference of coronoid against the anteromedial margin of the zygomatic arch.

- Treatment: Coronoidectomy

- Trismus-pseudo-camtodactyly syndrome is a rare combination of hand, foot and mouth abnormalities and trismus.

Miscellaneous disorders

[edit]- Functional disorders ( neuro-psychiatric), the emotional conflict are converted into a physical symptom. E.g.: trismus

- Scleroderma: A condition marked by edema and induration of the skin involving facial region can cause trismus

Common causes

[edit]- Pericoronitis (inflammation of soft tissue around impacted third molar) is the most common cause of trismus.[12]

- Inflammation of muscles of mastication.[12] It is a frequent sequel to surgical removal of mandibular third molars (lower wisdom teeth). The condition is usually resolved on its own in 10–14 days, during which time eating and oral hygiene are compromised. The application of heat (e.g. heat bag extraorally, and warm salt water intraorally) may help, reducing the severity and duration of the condition.

- Peritonsillar abscess,[12] a complication of tonsillitis which usually presents with sore throat, dysphagia, fever, and change in voice.

- Temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMD).[12]

- Trismus is often mistaken as a common temporary side effect of many stimulants of the sympathetic nervous system. Users of amphetamines as well as many other pharmacological agents commonly report bruxism as a side-effect; however, it is sometimes mis-referred to as trismus. Users' jaws do not lock, but rather the muscles become tight and the jaw clenched. It is still perfectly possible to open the mouth.[12]

- Submucous fibrosis.

- Fracture of the zygomatic arch.

- Oral sex

Other causes

[edit]- Acute osteomyelitis

- Ankylosis of the TMJ (fibrous or bony)

- Condylar fracture or other trauma.

- Gaucher disease which is caused by deficiency of the enzyme glucocerebrosidase.

- Giant cell arteritis

- Sympathomimetic drugs, such as amphetamine, methamphetamine, MDA, MDMA, MDEA, methylphenidate, ethylphenidate, and related substances.

- Infection

- Local anesthesia (dental injections into the infratemporal fossa)

- Needle prick to the medial pterygoid muscle

- Oral submucous fibrosis.

- Radiation therapy to the head and neck.

- Tetanus, also called lockjaw for this reason

- Malignant hyperthermia

- Malaria severa

- Secondary to neuroleptic drug use

- Malignant otitis externa

- Mumps

- Peritonsillar abscess

- Retropharyngeal or parapharyngeal abscess

- Seizure

- Stroke

- Toothache

Diagnostic approach

[edit]X-ray/CT scan taken from the TMJ to see if there is any damage to the TMJ and surrounding structures.[citation needed]

Treatment

[edit]Treatment requires treating the underlying condition with dental treatments, speech therapy for swallowing difficulty and mouth opening restrictions, physical therapy, and passive range of motion devices. Additionally, control of symptoms with pain medications (NSAIDs), muscle relaxants, and warm compresses may be used.

Splints have been used.[13]

History

[edit]Historically, the term trismus was used to describe the early effects of tetany, also called "lockjaw".

References

[edit]- ^ "Trismus – The Oral Cancer Foundation". 19 September 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Santiago-Rosado, Livia M.; Lewison, Cheryl S. (2023), "Trismus", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29630255, retrieved 2023-11-17

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Odell, Edward W., ed. (2010). Clinical problem solving in dentistry (3rd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 37–41. ISBN 9780443067846.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Soames, J.V.; Southam, J.C. (1998). Oral pathology (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 330. ISBN 019262895X.

- ^ "trismus". Miller-Keane Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health (Seventh ed.). 2003.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Kerawala, Cyrus; Newlands, Carrie, eds. (2010). Oral and maxillofacial surgery. Oxford specialist handbooks in surgery. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-920483-0. OCLC 403362622.

- ^ "Tetanus Symptoms and Complications | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2022-09-12. Retrieved 2023-11-17.

- ^ a b Scully, Crispian (2008). Oral and maxillofacial medicine: the basis of diagnosis and treatment (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 101, 353. ISBN 9780443068188.

- ^ Hupp JR, Ellis E, Tucker MR (2008). Contemporary oral and maxillofacial surgery (5th ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby Elsevier. ISBN 9780323049030.

- ^ "Etymology of Trismus on Online Etymology Dictionary". Douglas Harper. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ a b Kalantzis, Crispian Scully, Athanasios (2005). Oxford handbook of dental patient care (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198566236.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Chris (29 December 2011). "Dr". Locked Jaw (Lockjaw and Slack Jaw) Meaning and Causes |. Healthhype.com. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- ^ Shulman DH, Shipman B, Willis FB (2008). "Treating trismus with dynamic splinting: A cohort, case series". Adv Ther. 25 (1): 9–16. doi:10.1007/s12325-008-0007-0. PMID 18227979. S2CID 20495294.