Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Specular reflection

View on Wikipedia

Specular reflection, or regular reflection, is the mirror-like reflection of waves, such as light, from a surface.[1]

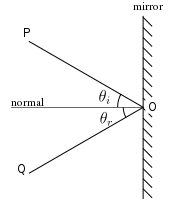

The law of reflection states that a reflected ray of light emerges from the reflecting surface at the same angle to the surface normal as the incident ray, but on the opposing side of the surface normal in the plane formed by the incident and reflected rays. The earliest known description of this behavior was recorded by Hero of Alexandria (AD c. 10–70).[2] Later, Alhazen gave a complete statement of the law of reflection.[3][4][5] He was first to state that the incident ray, the reflected ray, and the normal to the surface all lie in a same plane perpendicular to reflecting plane.[6][7]

Specular reflection may be contrasted with diffuse reflection, in which light is scattered away from the surface in a range of directions.

Law of reflection

[edit]

When light encounters a boundary of a material, it is affected by the optical and electronic response functions of the material to electromagnetic waves. Optical processes, which comprise reflection and refraction, are expressed by the difference of the refractive index on both sides of the boundary, whereas reflectance and absorption are the real and imaginary parts of the response due to the electronic structure of the material.[8] The degree of participation of each of these processes in the transmission is a function of the frequency, or wavelength, of the light, its polarization, and its angle of incidence. In general, reflection increases with increasing angle of incidence, and with increasing absorptivity at the boundary. The Fresnel equations describe the physics at the optical boundary.

Reflection may occur as specular, or mirror-like, reflection and diffuse reflection. Specular reflection reflects all light which arrives from a given direction at the same angle, whereas diffuse reflection reflects light in a broad range of directions. The distinction may be illustrated with surfaces coated with glossy paint and matte paint. Matte paints exhibit essentially complete diffuse reflection, while glossy paints show a larger component of specular behavior. A surface built from a non-absorbing powder, such as plaster, can be a nearly perfect diffuser, whereas polished metallic objects can specularly reflect light very efficiently. The reflecting material of mirrors is usually aluminum or silver.

Light propagates in space as a wave front of electromagnetic fields. A ray of light is characterized by the direction normal to the wave front (wave normal). When a ray encounters a surface, the angle that the wave normal makes with respect to the surface normal is called the angle of incidence and the plane defined by both directions is the plane of incidence. Reflection of the incident ray also occurs in the plane of incidence.

The law of reflection states that the angle of reflection of a ray equals the angle of incidence, and that the incident direction, the surface normal, and the reflected direction are coplanar.

When the light is incident perpendicularly to the surface, it is reflected straight back in the source direction.

The phenomenon of reflection arises from the diffraction of a plane wave on a flat boundary. When the boundary size is much larger than the wavelength, then the electromagnetic fields at the boundary are oscillating exactly in phase only for the specular direction.

Vector formulation

[edit]The law of reflection can also be equivalently expressed using linear algebra. The direction of a reflected ray is determined by the vector of incidence and the surface normal vector. Given an incident direction from the light source to the surface and the surface normal direction the specularly reflected direction (all unit vectors) is:[9][10]

where is a scalar obtained with the dot product. Different authors may define the incident and reflection directions with different signs. Assuming these Euclidean vectors are represented in column form, the equation can be equivalently expressed as a matrix-vector multiplication:[11]

where is the so-called Householder transformation matrix, defined as:

in terms of the identity matrix and twice the outer product of .

Reflectivity

[edit]Reflectivity is the ratio of the power of the reflected wave to that of the incident wave. It is a function of the wavelength of radiation, and is related to the refractive index of the material as expressed by Fresnel's equations.[12] In regions of the electromagnetic spectrum in which absorption by the material is significant, it is related to the electronic absorption spectrum through the imaginary component of the complex refractive index. The electronic absorption spectrum of an opaque material, which is difficult or impossible to measure directly, may therefore be indirectly determined from the reflection spectrum by a Kramers-Kronig transform. The polarization of the reflected light depends on the symmetry of the arrangement of the incident probing light with respect to the absorbing transitions dipole moments in the material.

Measurement of specular reflection is performed with normal or varying incidence reflection spectrophotometers (reflectometer) using a scanning variable-wavelength light source. Lower quality measurements using a glossmeter quantify the glossy appearance of a surface in gloss units.

Consequences

[edit]Internal reflection

[edit]When light is propagating in a material and strikes an interface with a material of lower index of refraction, some of the light is reflected. If the angle of incidence is greater than the critical angle, total internal reflection occurs: all of the light is reflected. The critical angle can be shown to be given by

Polarization

[edit]When light strikes an interface between two materials, the reflected light is generally partially polarized. However, if the light strikes the interface at Brewster's angle, the reflected light is completely linearly polarized parallel to the interface. Brewster's angle is given by

Reflected images

[edit]The image in a flat mirror has these features:

- It is the same distance behind the mirror as the object is in front.

- It is the same size as the object.

- It is the right way up (erect).

- It is reversed.

- It is virtual, meaning that the image appears to be behind the mirror, and cannot be projected onto a screen.

The reversal of images by a plane mirror is perceived differently depending on the circumstances. In many cases, the image in a mirror appears to be reversed from left to right. If a flat mirror is mounted on the ceiling it can appear to reverse up and down if a person stands under it and looks up at it. Similarly a car turning left will still appear to be turning left in the rear view mirror for the driver of a car in front of it. The reversal of directions, or lack thereof, depends on how the directions are defined. More specifically a mirror changes the handedness of the coordinate system, one axis of the coordinate system appears to be reversed, and the chirality of the image may change. For example, the image of a right shoe will look like a left shoe.

Examples

[edit]

A classic example of specular reflection is a mirror, which is specifically designed for specular reflection.

In addition to visible light, specular reflection can be observed in the ionospheric reflection of radiowaves and the reflection of radio- or microwave radar signals by flying objects. The measurement technique of x-ray reflectivity exploits specular reflectivity to study thin films and interfaces with sub-nanometer resolution, using either modern laboratory sources or synchrotron x-rays.

Non-electromagnetic waves can also exhibit specular reflection, as in acoustic mirrors which reflect sound, and atomic mirrors, which reflect neutral atoms. For the efficient reflection of atoms from a solid-state mirror, very cold atoms and/or grazing incidence are used in order to provide significant quantum reflection; ridged mirrors are used to enhance the specular reflection of atoms. Neutron reflectometry uses specular reflection to study material surfaces and thin film interfaces in an analogous fashion to x-ray reflectivity.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Tan, R.T. (2013). "Specularity, Specular Reflectance". In Ikeuchi, Katsushi (ed.). Computer Vision. Springer, Boston, MA. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-31439-6_538. ISBN 978-0-387-31439-6. S2CID 5058976.

- ^ Sir Thomas Little Heath (1981). A history of Greek mathematics. Volume II: From Aristarchus to Diophantus. ISBN 978-0-486-24074-9.

- ^ Stamnes, J. J. (2017-11-13). Waves in Focal Regions: Propagation, Diffraction and Focusing of Light, Sound and Water Waves. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-40468-6.

- ^ Mach, Ernst (2013-01-23). The Principles of Physical Optics: An Historical and Philosophical Treatment. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-17347-4.

- ^ Iizuka, Keigo (2013-11-11). Engineering Optics. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-662-07032-1.

- ^ Selin, Helaine (2008). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. p. 1817.

- ^ Mach, Ernst (2013-01-23). The Principles of Physical Optics: An Historical and Philosophical Treatment. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-17347-4.

- ^ Fox, Mark (2010). Optical properties of solids (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-19-957336-3.

- ^ Haines, Eric (2021). "Chapter 8: Reflection and Refraction Formulas". In Marrs, Adam; Shirley, Peter; Wald, Ingo (eds.). Ray Tracing Gems II. Apress. pp. 105–108. doi:10.1007/978-1-4842-7185-8_8. ISBN 978-1-4842-7185-8. S2CID 238899623.

- ^ Comninos, Peter (2006). Mathematical and computer programming techniques for computer graphics. Springer. p. 361. ISBN 978-1-85233-902-9. Archived from the original on 2018-01-14.

- ^ Farin, Gerald; Hansford, Dianne (2005). Practical linear algebra: a geometry toolbox. A K Peters. pp. 191–192. ISBN 978-1-56881-234-2. Archived from the original on 2010-03-07. Practical linear algebra: a geometry toolbox at Google Books

- ^ Hecht, Eugene (1987). Optics (2nd ed.). Addison Wesley. p. 100. ISBN 0-201-11609-X.