Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Leapfrog

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2024) |

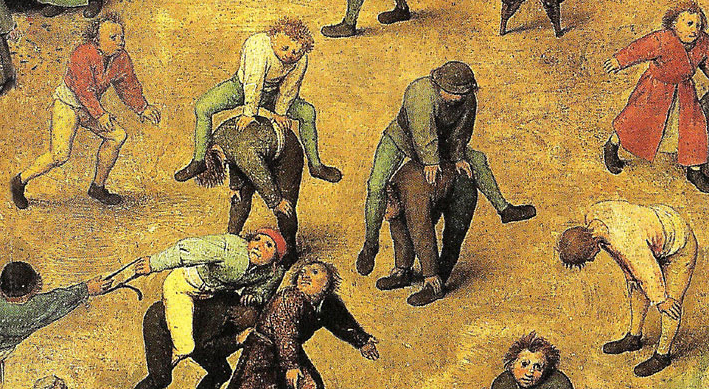

Leapfrog is a children's game of physical movement of the body in which players vault over each other's stooped backs. The term has also become a verb describing any situation in which a person or entity at the rear of a line advances directly to the front.

History

[edit]Games of this sort have been called by this name since at least the late sixteenth century.[1]

Gameplay

[edit]The first participant remains still after placing their hands on their own knees while bending forward, a move known as giving a back.[citation needed] The next player swiftly dashes forward, briefly plants their hands on the first player's back for support (while straddling legs wide apart) while hoping to vault over the first player. This jumper, upon landing, advances a few steps ahead and then gives a back by vaulting over in the next participant in the same manner as the first player. (Meanwhile, the first player continues giving a back.) A third player leaps over the first two participants and also gives a back by vaulting over. A fourth jumper would leap over all previous jumpers successively. Additional players can join in the same way: leaping over others and then vaulting over (giving a back) to be jumped over by the next. The number of participants is not fixed. When all players are eventually stopped, the last person in line begins leaping over all the others in turn. The length of gameplay and determining the winner (if any) is not standardized; participants decide among themselves.

Variations

[edit]

The French version of this game is called saute-mouton (literally "leapsheep"), and the Romanian is called capra ("mounting rack" or "goat"). In India it is known as Aar Ghodi Ki Par Ghodi in Hindi (meaning horseleap). In Italy the game is called la cavallina (i.e. small or baby female horse). In Dutch it is called bokspringen (literally goatjumping; a bok is a male goat) or haasje-over (literally hare-over).[citation needed]

In China this game is known as [citation needed] leap goat ("跳山羊"), which is played in pairs. One player, acting as "the goat", leaps over the back of the other player, who plays the role of "the rock/mountain". Then they switch roles, and "the rock" rises a bit each time they switch. Both players continue playing until one "goat" fails leaping "the rock/mountain" as the result of its rising.

In the Filipino culture, a similar game is called luksóng báka (literally "leap cow"), in which the "it" rests his hands on his knees and bends over, and then the other players —in succession—place their hands on the back of the “it” and leaps over by straddling legs wide apart on each side; whoever's legs touch any part of the body of the “it” becomes the next “it.”

In the Korean and Japanese versions (말뚝박기 lit. "piledriving" and 馬跳び うまとび umatobi, lit. "horseleap", respectively), one player 'leaps' over the backs of the other players who stoop close enough to form a continuous line, attempting to cause the line to collapse under the weight of the riders.[citation needed]

At times, leapfrog's demanding physical exertion was coercively forced upon unwilling adults, as happened at some Nazi German camps. Bundesarchiv photos document such activity having occurred at Mauthausen concentration camp and other sites.

References

[edit]- ^ Leap-frog, n, Oxford English Dictionary. Accessed 2008-10-21.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Leapfrog at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Leapfrog at Wikimedia Commons

Leapfrog

View on GrokipediaLeapfrog is a children's game in which players take turns vaulting over the stooped backs of others who bend forward from the waist with hands on knees.[1][2] The leaping player places hands on the back of the bent player for support before jumping over, often in a line where each jumper becomes the next base.[1] This physical activity emphasizes agility, coordination, and balance, commonly played outdoors in groups.[3] Variants include competitive versions where players attempt to leap over multiple bases in sequence or incorporate rules for elimination based on failed jumps.[4] The game derives its name from the frog-like leaping motion and has been documented in English-speaking cultures since the late 16th century.[5]