Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Macrocycle

View on Wikipedia

Macrocycles are often described as molecules and ions containing a ring of twelve or more atoms.[2] Classical examples include the crown ethers, calixarenes, porphyrins, and cyclodextrins. Macrocycles describe a large, mature area of chemistry.[3]

Macrocycle: Cyclic macromolecule or a macromolecular cyclic portion of a macromolecule. Note 1: A cyclic macromolecule has no end-groups but may nevertheless be regarded as a chain.

Note 2: In the literature, the term macrocycle is sometimes used for molecules of low relative molecular mass that would not be considered macromolecules.[4]

Synthesis

[edit]The formation of macrocycles by ring-closure is called macrocyclization.[5] The central challenge to macrocyclization is that ring-closing reactions do not favor the formation of large rings. Instead, medium sized rings or polymers tend to form. Early macrocyclizations were achieved ketonic decarboxylations for the preparation of terpenoid macrocycles. So, while Ružička was able to produce various macrocycles, the yields were low.[6] This kinetic problem can be addressed by using high-dilution reactions, whereby intramolecular processes are favored relative to polymerizations.[7] Reactions amenable to high dilution include Dieckmann condensation and related based-induced reactions of esters with remote halides.

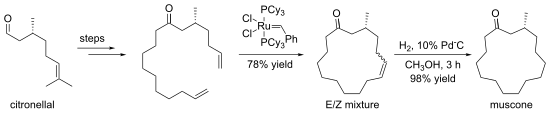

Some macrocyclizations are achieved using template reactions. Templates are ions, molecules, surfaces etc. that bind and pre-organize reactants, guiding them toward formation of a particular ring size.[8] The crown ethers are often generated in the presence of an alkali metal cation, which organizes the condensing components by complexation.[9] An illustrative macrocyclization is the synthesis of (−)-muscone from (+)-citronellal. The 15-membered ring is generated by ring-closing metathesis.[10]

Stereocontrol

[edit]Macrocyclic stereocontrol refers to the directed outcome of a given intermolecular or intramolecular reaction that is governed by the conformational preference of a macrocycle. Stereocontrol for cyclohexane rings is well established in organic chemistry, in large part due to the axial/equatorial preferential positioning of substituents on the ring. Macrocyclic stereocontrol models the substitution and reactions of medium and large rings in organic chemistry, with remote stereogenic elements providing enough conformational influence to direct the outcome of a reaction.

Early assumptions towards macrocycles in synthetic chemistry considered them far too floppy to provide any degree of stereochemical or regiochemical control in a reaction. Investigations in the late 1970s and 1980s challenged this assumption,[12] while several others found crystallographic data [13] and NMR data [14] that suggested macrocyclic rings were not the floppy, conformationally ill-defined species many assumed.

The rigidity of a macrocyclic ring depends significantly on the substitution and the overall size.[15][16] Significantly, even small conformational preferences, such as those envisioned in floppy macrocycles, can profoundly influence the ground state of a given reaction, providing stereocontrol such as in the synthesis of miyakolide.[17]

Reaction classes used in synthesis of natural products under the macrocyclic stereocontrol model for obtaining a desired stereochemistry include: hydrogenations such as in neopeltolide [18] and (±)-methynolide,[19] epoxidations such as in (±)-periplanone B[20] and lonomycin A,[21] hydroborations such as in 9-dihydroerythronolide B,[22] enolate alkylations such as in (±)-3-deoxyrosaranolide,[23] dihydroxylations such as in cladiell-11-ene-3,6,7-triol,[24] and reductions such as in eucannabinolide.[25]

Conformational preferences

[edit]Macrocycles can access a number of stable conformations, with preferences to reside in those that minimize the number of transannular nonbonded interactions within the ring.[16] Medium rings (8-11 atoms) are the most strained with between 9-13 (kcal/mol) strain energy; analysis of the factors important in considering larger macrocyclic conformations can thus be modeled by looking at medium ring conformations.[26][page needed] Conformational analysis of odd-membered rings suggests they tend to reside in less symmetrical forms with smaller energy differences between stable conformations.[27]

Cyclooctane

[edit]

Conformational analysis of medium rings begins with examination of cyclooctane. Spectroscopic methods have determined that cyclooctane possesses three main conformations: chair-boat, chair-chair, and boat-boat. Cyclooctane prefers to reside in a chair-boat conformation, minimizing the number of eclipsing ethane interactions (shown in blue), as well as torsional strain.[28] The chair-chair conformation is the second most abundant conformation at room temperature, with a ratio of 96:4 chair-boat:chair-chair observed.[12]

Substitution positional preferences in the ground state conformer of methyl cyclooctane can be approximated using parameters similar to those for smaller rings. In general, the substituents exhibit preferences for equatorial placement, except for the lowest energy structure (pseudo A-value of -0.3 kcal/mol in figure below) in which axial substitution is favored. The "pseudo A-value" is best treated as the approximate energy difference between placing the methyl substituent in the equatorial or axial positions. The most energetically unfavorable interaction involves axial substitution at the vertex of the boat portion of the ring (6.1 kcal/mol).

These energetic differences can help rationalize the lowest energy conformations of 8 atom ring structures containing an sp2 center. In these structures, the chair-boat is the ground state model, with substitution forcing the structure to adopt a conformation such that non-bonded interactions are minimized from the parent structure.[29] From the cyclooctene figure below, it can be observed that one face is more exposed than the other, foreshadowing a discussion of privileged attack angles (see peripheral attack).

X-ray analysis of functionalized cyclooctanes provided proof of conformational preferences in these medium rings. Significantly, calculated models matched the obtained X-ray data, indicating that computational modeling of these systems could in some cases quite accurately predict conformations. The increased sp2 character of the cyclopropane rings favor them to be placed similarly such that they relieve non-bonded interactions.[30]

Cyclodecane

[edit]

Similar to cyclooctane, a cyclodecane ring exhibits several conformations with two lower energy conformations. The boat-chair-boat conformation is energetically minimized, while the chair-chair-chair conformation has significant eclipsing interactions.

These ground-state conformational preferences are useful analogies to more highly functionalized macrocyclic ring systems, where local effects can still be governed to first approximation by energy minimized conformations even though the larger ring size allows more conformational flexibility of the entire structure. For example, in methyl cyclodecane, the ring can be expected to adopt the minimized conformation of boat-chair-boat. The figure below shows the energetic penalty between placing the methyl group at certain sites within the boat-chair-boat structure. Unlike canonical small ring systems, the cyclodecane system with the methyl group placed at the "corners" of the structure exhibits no preference for axial vs. equatorial positioning due to the presence of an unavoidable gauche-butane interaction in both conformations. Significantly more intense interactions develop when the methyl group is placed in the axial position at other sites in the boat-chair-boat conformation.[12]

Larger ring systems

[edit]Similar principles guide the lowest energy conformations of larger ring systems. Along with the acyclic stereocontrol principles outlined below, subtle interactions between remote substituents in large rings, analogous to those observed for 8-10 membered rings, can influence the conformational preferences of a molecule. In conjunction with remote substituent effects, local acyclic interactions can also play an important role in determining the outcome of macrocyclic reactions.[31] The conformational flexibility of larger rings potentially allows for a combination of acyclic and macrocyclic stereocontrol to direct reactions.[31]

Reactivity and conformational preferences

[edit]The stereochemical result of a given reaction on a macrocycle capable of adopting several conformations can be modeled by a Curtin-Hammett scenario. In the diagram below, the two ground state conformations exist in an equilibrium, with some difference in their ground state energies. Conformation B is lower in energy than conformation A, and while possessing a similar energy barrier to its transition state in a hypothetical reaction, thus the product formed is predominantly product B (P B) arising from conformation B via transition state B (TS B). The inherent preference of a ring to exist in one conformation over another provides a tool for stereoselective control of reactions by biasing the ring into a given configuration in the ground state. The energy differences, ΔΔG‡ and ΔG0 are significant considerations in this scenario. The preference for one conformation over another can be characterized by ΔG0, the free energy difference, which can, at some level, be estimated from conformational analysis. The free energy difference between the two transition states of each conformation on its path to product formation is given by ΔΔG‡. The value of ΔG0 between not just one, but many accessible conformations is the underlying energetic impetus for reactions occurring from the most stable ground state conformation and is the crux of the peripheral attack model outlined below.[32]

The peripheral attack model

[edit]Macrocyclic rings containing sp2 centers display a conformational preference for the sp2 centers to avoid transannular nonbonded interactions by orienting perpendicular to the plan of the ring. W. Clark Still proposed that the ground state conformations of macrocyclic rings, containing the energy minimized orientation of the sp2 center, display one face of an olefin outwards from the ring.[12][20][23] Addition of reagents from the outside the olefin face and the ring (peripheral attack) is thus favored, while attack from across the ring on the inward diastereoface is disfavored. Ground state conformations dictate the exposed face of the reactive site of the macrocycle, thus both local and distant stereocontrol elements must be considered. The peripheral attack model holds well for several classes of macrocycles, though relies on the assumption that ground state geometries remain unperturbed in the corresponding transition state of the reaction.

Early investigations of macrocyclic stereocontrol studied the alkylation of 8-membered cyclic ketones with varying substitution.[12] In the example below, alkylation of 2-methylcyclooctanone occurred to yield the predominantly trans product. Proceeding from the lowest energy conformation of 2-methylcycloctanone, peripheral attack is observed from either one of the low energy (energetic difference of 0.5 (kcal/mol)) enolate conformations, resulting in a trans product from either of the two depicted transition state conformations.[33]

Unlike the cyclooctanone case, alkylation of 2-cyclodecanone rings does not display significant diastereoselectivity.[12]

However, 10-membered cyclic lactones display significant diastereoselectivity.[12] The proximity of the methyl group to the ester linkage was directly correlated with the diastereomeric ratio of the reaction products, with placement at the 9 position (below) yielding the highest selectivity. In contrast, when the methyl group was placed at the 7 position, a 1:1 mixture of diastereomers was obtained. Placement of the methyl group at the 9-position in the axial position yields the most stable ground state conformation of the 10-membered ring leading to high diastereoselectivity.

Conjugate addition to the E-enone below also follows the expected peripheral attack model to yield predominantly trans product.[33] High selectivity in this addition can be attributed to the placement of sp2 centers such that transannular nonbonded interactions are minimized, while also placing the methyl substitution in the more energetically favorable position for cyclodecane rings. This ground state conformation heavily biases conjugate addition to the less hindered diastereoface.

Similar to intermolecular reactions, intramolecular reactions can show significant stereoselectivity from the ground state conformation of the molecule. In the intramolecular Diels-Alder reaction depicted below, the lowest energy conformation yields the observed product.[34] The structure minimizing repulsive steric interactions provides the observed product by having the lowest barrier to a transition state for the reaction. Though no external attack by a reagent occurs, this reaction can be thought of similarly to those modeled with peripheral attack; the lowest energy conformation is the most likely to react for a given reaction.

The lowest energy conformations of macrocycles also influence intramolecular reactions involving transannular bond formation. In the intramolecular Michael addition sequence below, the ground state conformation minimizes transannular interactions by placing the sp2 centers at the appropriate vertices, while also minimizing diaxial interactions.[35]

Prominent examples in synthesis

[edit]These principles have been applied in multiple natural product targets containing medium and large rings. The syntheses of cladiell-11-ene-3,6,7- triol,[24] (±)-periplanone B,[20] eucannabinolide,[25] and neopeltolide[18] are all significant in their usage of macrocyclic stereocontrol en route to the desired structural targets.

Cladiell-11-ene-3,6,7-triol

[edit]The cladiellin family of marine natural products feature 9-membered rings. The synthesis of (−)-cladiella-6,11-dien-3-ol allowed access to a variety of other members of the cladiellin family. The conversion to cladiell-11-ene-3,6,7-triol makes use of macrocyclic stereocontrol in the dihydroxylation of a trisubstituted olefin. Below is shown the synthetic step controlled by the ground state conformation of the macrocycle, allowing stereoselective dihydroxylation without the usage of an asymmetric reagent. This example of substrate controlled addition is an example of the peripheral attack model in which two centers on the molecule are added two at once in a concerted fashion.

(±)-Periplanone B

[edit]The synthesis of (±)-periplanone B is a prominent example of macrocyclic stereocontrol.[20] Periplanone B is a sex pheromone of the American female cockroach, and has been the target of several synthetic attempts. Significantly, two reactions on the macrocyclic precursor to (±)-periplanone B were directed using only ground state conformational preferences and the peripheral attack model. Reacting from the most stable boat-chair-boat conformation, asymmetric epoxidation of the cis-internal olefin can be achieved without using a reagent-controlled epoxidation method or a directed epoxidation with an allylic alcohol.

Epoxidation of the ketone was achieved, and can be modeled by peripheral attack of the sulfur ylide on the carbonyl group in a Johnson-Corey-Chaykovsky reaction to yield the protected form of (±)-periplanone B. Deprotection of the alcohol followed by oxidation yielded the desired natural product.

Eucannabinolide

[edit]In the synthesis of the cytotoxic germacranolide sesquiterpene eucannabinolide, Still demonstrates the application of the peripheral attack model to the reduction of a ketone to set a new stereocenter using NaBH4. Significantly, the synthesis of eucannabinolide relied on the usage of molecular mechanics (MM2) computational modeling to predict the lowest energy conformation of the macrocycle to design substrate-controlled stereochemical reactions.

Neopeltolide

[edit]Neopeltolide was originally isolated from sponges near the Jamaican coast and exhibits nanomolar cytoxic activity against several lines of cancer cells. The synthesis of the neopeltolide macrocyclic core displays a hydrogenation controlled by the ground state conformation of the macrocycle.

Occurrence and applications

[edit]One important application are the many macrocyclic antibiotics, the macrolides, e.g. clarithromycin. Many metallocofactors are bound to macrocyclic ligands, which include porphyrins, corrins, and chlorins. These rings arise from multistep biosynthetic processes that also feature macrocycles.

Macrocycles often bind ions and facilitate ion transport across hydrophobic membranes and solvents. The macrocycle envelops the ion with a hydrophobic sheath, which facilitates phase transfer properties.[36]

Macrocycles are often bioactive and could be useful for drug delivery.[37][38]

Macrocycles in Drug Discovery

[edit]Over the last few years, macrocyclic molecules have become increasingly relevant in drug discovery. For a long time, this motif was found almost exclusively in natural products (s. Cyclosporine), but it can now also be found in some completely synthetic molecules (s. Grazoprevir).[39]

Special focus is placed on macrocyclic peptides, as these are comparatively easy to produce. In addition, their risk is classified as comparatively low because, like the body's own proteins, they consist of amino acids (which can, however, be modified).[40] Normally it is difficult for molecules above a certain size and number of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors to get absorbed orally.[41] However, it is now possible to make these molecules bio-orally available through certain modifications of the amino acids and through high N-alkylation.[42][43] A chameleon-like behaviour of such molecules can also be observed, because the parts of the molecules that are directed outwards and inwards can change depending on the environment and thus influence the solubility.[44][45]

Subdivisions

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hamilton-Miller, JM (1973). "Chemistry and Biology of the Polyene Macrolide Antibiotics". Bacteriological Reviews. 37 (2): 166–196. doi:10.1128/br.37.2.166-196.1973. PMC 413810. PMID 4578757.

- ^ Garcia Jimenez, Diego; Poongavanam, Vasanthanathan; Kihlberg, Jan (2023). "Macrocycles in Drug Discovery─Learning from the Past for the Future". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 66 (8): 5377–5396. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00134. PMC 10150360. PMID 37017513.

Macrocycles are generally defined as organic molecules which contain a ring of at least 12 heavy atoms.

- ^ Zhichang Liu; Siva Krishna Mohan Nalluria; J. Fraser Stoddart (2017). "Surveying macrocyclic chemistry: from flexible crown ethers to rigid cyclophanes". Chemical Society Reviews. 46 (9): 2459–2478. doi:10.1039/c7cs00185a. PMID 28462968.

- ^ R. G. Jones; J. Kahovec; R. Stepto; E. S. Wilks; M. Hess; T. Kitayama; W. V. Metanomski (2008). IUPAC. Compendium of Polymer Terminology and Nomenclature, IUPAC Recommendations 2008 (the "Purple Book") (PDF). RSC Publishing, Cambridge, UK.

- ^ François Diederich; Peter J. Stang; Rik R. Tykwinski, eds. (2008). Modern Supramolecular Chemistry: Strategies for Macrocycle Synthesis. Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/9783527621484. ISBN 9783527621484.

- ^ H. Höcker (2009). "Cyclic and Macrocyclic OrganicCompounds – a Personal Review in Honor of Professor Leopold Ružička". Cyclic and Macrocyclic Organic Compounds, Kem. Ind. 58: 73–80.

- ^ Vicente Martí-Centelles; Mrituanjay D. Pandey; M. Isabel Burguete; Santiago V. Luis (2015). "Macrocyclization Reactions: The Importance of Conformational, Configurational, and Template-Induced Preorganization". Chem. Rev. 115 (16): 8736–8834. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00056. hdl:10234/154905. PMID 26248133.

- ^ Gerbeleu, Nicolai V.; Arion, Vladimir B.; Burgess, John (2007). Nicolai V. Gerbeleu; Vladimir B. Arion; John Burgess (eds.). Template Synthesis of Macrocyclic Compounds. Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/9783527613809. ISBN 9783527613809.

- ^ Pedersen, Charles J. (1988). "Macrocyclic Polyethers: Dibenzo-18-Crown-6 Polyether and Dicyclohexyl-18-Crown-6 Polyether". Organic Syntheses; Collected Volumes, vol. 6, p. 395.

- ^ Kamat, V.P.; Hagiwara, H.; Katsumi, T.; Hoshi, T.; Suzuki, T.; Ando, M. (2000). "Ring Closing Metathesis Directed Synthesis of (R)-(−)-Muscone from (+)-Citronellal". Tetrahedron. 56 (26): 4397–4403. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(00)00333-1.

- ^ Paul R. Ortiz de Montellano (2008). "Hemes in Biology". Wiley Encyclopedia of Chemical Biology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–10. doi:10.1002/9780470048672.wecb221. ISBN 978-0470048672.

- ^ a b c d e f g Still, W. C.; Galynker, I. Tetrahedron 1981, 37, 3981-3996.

- ^ J. D. Dunitz. Perspectives in Structural Chemistry (Edited by J. D. Dunitz and J. A. Ibers), Vol. 2, pp. l-70; Wiley, New York (1968)

- ^ Anet, F. A. L.; Degen, P. J.; Yavari. I. J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 3021-3023.

- ^ Casarini, D.; Lunazzi, L.; Mazzanti, A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 2035-2056.

- ^ a b Kamenik, Anna S.; Lessel, Uta; Fuchs, Julian E.; Fox, Thomas; Liedl, Klaus R. (2018). "Peptidic Macrocycles - Conformational Sampling and Thermodynamic Characterization". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 58 (5): 982–992. doi:10.1021/acs.jcim.8b00097. PMC 5974701. PMID 29652495.

- ^ Evans, D. A.; Ripin, D.H.B.; Halstead, D.P.; Campos, K. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 6816-6826.

- ^ a b Tu, W.; Floreancig, P. E. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 4567-4571.

- ^ Vedejs, E.; Buchanan, R.A.; Watanabe, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 8430-8438.

- ^ a b c d Still, W.C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101, 2493-2495.

- ^ Evans, D.A.; Ratz, A.M.; Huff, B.E.; and Sheppard, G.S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 3448-3467.

- ^ Mulzer, J.; Kirstein, H.M.; Buschmann, J.; Lehmann, C.; Luger, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 910-923.

- ^ a b Still, W. Clark; Novack, Vance (February 1984). "Macrocyclic Stereocontrol. Total Synthesis of (±)-3-Deoxyrosaranolide". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 106 (4): 1148–1149. Bibcode:1984JAChS.106.1148S. doi:10.1021/ja00316a072.

- ^ a b Kim, H.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 15851-15855.

- ^ a b Still, W.C.; Murata, S.; Revial, G.; Yoshihara, K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 625-627.

- ^ Eliel, E.L., Wilen, S.H. and Mander, L.S. (1994) Stereochemistry of Organic Compounds, John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York.[page needed]

- ^ Anet, F.A.L.; St. Jacques, M.; Henrichs, P.M.; Cheng, A.K.; Krane, J.; Wong, L. Tetrahedron 1974, 30, 1629-1637.

- ^ Petasis, N. A.; Patane, M.A. Tetrahedron 1992, 48, 5757-5821.

- ^ Pawar, D.M.; Moody, E.M.; Noe, E.A. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 4586-4589.

- ^ Schreiber, S. L.; Smith, D. B.; Schulte, G. J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 5994-5996.

- ^ a b Deslongchamps, P. Pure Appl. Chem. 1992, 64, 1831-1847.

- ^ Seeman, J. I. Chem. Rev. 1983, 83, 83-134.

- ^ a b "Classics in Stereoselective Synthesis". Carreira, Erick M.; Kvaerno, Lisbet. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH, 2009. pp 1-16.

- ^ Deslongchamps, P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008,130, 13989-13995.

- ^ Scheerer, J.R.; Lawrence, J.F.; Wang, G.C.; Evans, D.A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 8968-8969.

- ^ Choi, Kihang; Hamilton, Andrew D. (2003). "Macrocyclic anion receptors based on directed hydrogen bonding interactions". Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 240 (1–2): 101–110. doi:10.1016/s0010-8545(02)00305-3.

- ^ Ermert, Philipp (2017-10-25). "Design, Properties and Recent Application of Macrocycles in Medicinal Chemistry". CHIMIA International Journal for Chemistry. 71 (10): 678–702. doi:10.2533/chimia.2017.678. PMID 29070413.

- ^ Marsault, Eric; Peterson, Mark L. (2011-04-14). "Macrocycles Are Great Cycles: Applications, Opportunities, and Challenges of Synthetic Macrocycles in Drug Discovery". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 54 (7): 1961–2004. doi:10.1021/jm1012374. ISSN 0022-2623. PMID 21381769.

- ^ Garcia Jimenez, Diego; Poongavanam, Vasanthanathan; Kihlberg, Jan (2023-04-27). "Macrocycles in Drug Discovery─Learning from the Past for the Future". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 66 (8): 5377–5396. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00134. ISSN 0022-2623. PMC 10150360. PMID 37017513.

- ^ Zhang, Huiya; Chen, Shiyu (2022-01-05). "Cyclic peptide drugs approved in the last two decades (2001–2021)". RSC Chemical Biology. 3 (1): 18–31. doi:10.1039/D1CB00154J. ISSN 2633-0679. PMC 8729179. PMID 35128405.

- ^ Lipinski, Christopher A.; Lombardo, Franco; Dominy, Beryl W.; Feeney, Paul J. (1997-01-15). "Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings". Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. In Vitro Models for Selection of Development Candidates. 23 (1): 3–25. doi:10.1016/S0169-409X(96)00423-1. ISSN 0169-409X.

- ^ Tanada, Mikimasa; Tamiya, Minoru; Matsuo, Atsushi; Chiyoda, Aya; Takano, Koji; Ito, Toshiya; Irie, Machiko; Kotake, Tomoya; Takeyama, Ryuuichi; Kawada, Hatsuo; Hayashi, Ryuji; Ishikawa, Shiho; Nomura, Kenichi; Furuichi, Noriyuki; Morita, Yuya (2023-08-02). "Development of Orally Bioavailable Peptides Targeting an Intracellular Protein: From a Hit to a Clinical KRAS Inhibitor". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 145 (30): 16610–16620. Bibcode:2023JAChS.14516610T. doi:10.1021/jacs.3c03886. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 37463267.

- ^ Merz, Manuel L.; Habeshian, Sevan; Li, Bo; David, Jean-Alexandre G. L.; Nielsen, Alexander L.; Ji, Xinjian; Il Khwildy, Khaled; Duany Benitez, Maury M.; Phothirath, Phoukham; Heinis, Christian (May 2024). "De novo development of small cyclic peptides that are orally bioavailable". Nature Chemical Biology. 20 (5): 624–633. doi:10.1038/s41589-023-01496-y. ISSN 1552-4469. PMC 11062899. PMID 38155304.

- ^ Linker, Stephanie M.; Schellhaas, Christian; Kamenik, Anna S.; Veldhuizen, Mac M.; Waibl, Franz; Roth, Hans-Jörg; Fouché, Marianne; Rodde, Stephane; Riniker, Sereina (2023-02-23). "Lessons for Oral Bioavailability: How Conformationally Flexible Cyclic Peptides Enter and Cross Lipid Membranes". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 66 (4): 2773–2788. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01837. ISSN 0022-2623. PMC 9969412. PMID 36762908.

- ^ Sethio, Daniel; Poongavanam, Vasanthanathan; Xiong, Ruisheng; Tyagi, Mohit; Duy Vo, Duc; Lindh, Roland; Kihlberg, Jan (2023-01-09). "Simulation Reveals the Chameleonic Behavior of Macrocycles". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 63 (1): 138–146. doi:10.1021/acs.jcim.2c01093. ISSN 1549-9596. PMC 9832480. PMID 36563083.

Further reading

[edit]- Chambron, J-C.; Dietrich-Buchecker, C.; Hemmert, C.; Khemiss, A-K.; Mitchell, D.; Sauvage, J-P.; Weiss, J. (1990). "Interlacing molecular threads on transition metals" (PDF). Pure Appl. Chem. 62 (6): 1027–34. doi:10.1351/pac199062061027. S2CID 21741762.

- Iyoda, Masahiko; Yamakawa, Jun; Rahman, M. Jalilur (2011-11-04). "Conjugated Macrocycles: Concepts and Applications". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 50 (45): 10522–10553. doi:10.1002/anie.201006198. ISSN 1521-3773. PMID 21960431.

Macrocycle

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Classification

Definition

A macrocycle is defined in organic chemistry as a molecule or ion containing a ring composed of twelve or more atoms, distinguishing it from smaller cyclic compounds. This ring size criterion is widely adopted in the literature to encompass a diverse class of structures, including both carbocyclic and heterocyclic variants, where the cyclic framework enables unique topological and functional properties. Although the strict IUPAC definition from polymer chemistry describes a macrocycle as a cyclic macromolecule or a cyclic portion of a macromolecule, in supramolecular and organic contexts, the term is routinely applied to lower molecular weight species meeting the atom count threshold, without implying polymeric scale.[11][12][1] The concept of macrocycles gained prominence in the 1960s through the work of Charles J. Pedersen, who coined the term in reference to cyclic polyethers during his discovery of crown ethers. Pedersen's serendipitous synthesis of dibenzo-18-crown-6 in 1961, detailed in his seminal 1967 publication, marked the inception of systematic research into these compounds, highlighting their ability to form complexes with metal cations and laying the foundation for supramolecular chemistry. This historical distinction emphasized macrocycles as larger rings, in contrast to common small cycles like cyclohexane, which exhibit significant angle and torsional strain due to their constrained geometry.[13][14][15] Larger ring sizes in macrocycles generally minimize angle strain and steric repulsion compared to smaller rings, promoting conformational flexibility that allows adoption of multiple stable geometries. This flexibility facilitates the formation of internal cavities capable of hosting guest molecules or ions through non-covalent interactions, a key feature enabling applications in recognition and binding. A representative simple hydrocarbon macrocycle is cyclododecane, a 12-membered all-carbon ring that exemplifies these traits without heteroatoms or functional groups, serving as a baseline for understanding unadorned cyclic topology.[16][17][18]Types of Macrocycles

Macrocycles are broadly classified by the number of atoms in the ring and their elemental composition, with rings containing 12 or more atoms typically qualifying as macrocycles to distinguish them from smaller cyclic compounds. This classification emphasizes the role of composition in determining properties such as flexibility, binding affinity, and stability. Carbocycles, composed solely of carbon atoms, represent the simplest form and include examples like cyclooctadecane, a saturated 18-membered ring (C18H36) known for its conformational flexibility due to minimal ring strain. Heterocycles incorporate one or more heteroatoms such as oxygen, nitrogen, or sulfur into the carbon framework, which often introduces donor sites for coordination or host-guest interactions; crown ethers, featuring multiple oxygen atoms in an all-single-bond ring, exemplify this class and selectively bind alkali metal cations like K+ through electrostatic interactions. Metallomacrocycles integrate a central metal ion coordinated by the ring's donor atoms, enhancing electronic and catalytic properties; porphyrins, with four pyrrole units linked by methine bridges and a nitrogen-coordinated metal center (e.g., iron in heme), are a prototypical subclass valued for their role in oxygen transport and light harvesting.[19] Key subclasses of macrocycles further diversify their applications based on structural motifs. Crown ethers, first synthesized by Pedersen, are polyether heterocycles named by ring size and oxygen count (e.g., 18-crown-6 for an 18-atom ring with six oxygens), prized for their ionophoric properties in phase-transfer catalysis and sensor design. Cyclodextrins consist of six to eight glucose units linked by α-1,4-glycosidic bonds, forming toroidal sugar-based heterocycles with hydrophobic interiors that encapsulate guest molecules in aqueous media, as established in foundational enzymatic hydrolysis studies. Calixarenes, derived from p-tert-butylphenol and formaldehyde, adopt a vase-like conformation from typically four to eight phenolic units, enabling cavity-based recognition of cations and neutral guests through hydrogen bonding and π-interactions.[20] Pillararenes feature five para-substituted hydroquinone units linked at para positions, yielding rigid, cylindrical aromatic macrocycles with planar symmetry that excel in supramolecular assembly and stimuli-responsive materials. Peptide macrocycles, formed by cyclizing linear peptides via amide or disulfide bonds, mimic natural constraints to improve proteolytic stability and bioavailability, as seen in therapeutic agents like cyclosporine A. Structural variations within macrocycles influence their dynamics and functionality. Saturated macrocycles, characterized by all single bonds, exhibit high conformational flexibility, facilitating adaptive binding but potentially complicating preorganization; crown ethers and cyclooctadecane illustrate this, with multiple low-energy conformers accessible at room temperature. In contrast, unsaturated macrocycles incorporate double bonds, triple bonds, or aromatic systems, imparting rigidity and planarity that stabilize specific geometries; porphyrins and pillararenes demonstrate this through conjugated π-systems that enable electron delocalization and chromophoric behavior. Bridged macrocycles feature additional covalent connections between non-adjacent ring atoms, restricting flexibility and creating defined cavities compared to unbridged counterparts; examples include silicon- or biaryl-bridged variants that enhance steric control in coordination chemistry. These variations allow tailoring of macrocycle properties for targeted applications, though larger rings generally show increased conformational entropy.[19] Nomenclature for macrocycles follows IUPAC guidelines to reflect composition, size, and substitution systematically. For carbocycles, the von Baeyer system uses the "cyclo-" prefix followed by the total carbon count and alkane suffix, as in cyclooctadecane for an unbranched 18-carbon ring. Heterocyclic macrocycles employ Hantzsch-Widman prefixes for heteroatoms (e.g., oxa- for oxygen, aza- for nitrogen) combined with cyclo- and a locant for ring size, though trivial names prevail for established classes like -crown-m (n = total atoms, m = heteroatoms). Metallomacrocycles are named by specifying the ligand (e.g., porphine for the parent) followed by the metal and oxidation state, such as magnesium porphine in chlorophyll. Functionalized types often use specific descriptors like calixarene for n phenolic units or pillararene for n arene subunits, prioritizing clarity over exhaustive systematic naming in supramolecular contexts.[11]Structural Properties

Conformational Preferences

Macrocycles containing at least 12 atoms generally exhibit low overall ring strain compared to smaller cycloalkanes, enabling a greater number of accessible conformations due to reduced angle strain and the ability to adopt non-planar geometries that minimize torsional (Pitzer) strain.[21] In these systems, Pitzer strain arises from eclipsed or gauche interactions along the ring backbone, while transannular interactions—steric repulsions between non-adjacent atoms across the ring—play a dominant role in determining energy minima, often leading to flexible, dynamic structures rather than rigid ones.[21] This balance allows macrocycles to sample multiple low-energy conformers, with energy barriers low enough for interconversion at ambient temperatures.[21] Illustrative examples from larger cycloalkanes highlight these principles for macrocyclic systems. Larger rings, such as cyclooctadecane, further reduce strain and favor near-planar or elliptical shapes, like the or conformations (denoting sequences of trans and gauche bonds), where the ring adopts an elongated, oval profile to minimize both Pitzer and transannular effects, approaching the flexibility of acyclic alkanes.[22] In heteroatom-containing macrocycles like 18-crown-6, multiple low-energy conformations such as chair, boat, and twist-boat forms are accessible, influenced by lone-pair repulsions and solvation, enabling selective ion binding.[23] Conformational preferences in macrocycles are probed using NMR spectroscopy, which reveals dynamic equilibria through chemical shift averaging and coupling constants; for instance, 13C-NMR spectra of cycloalkanes up to C20 show distinct signals for individual conformers that merge upon ensemble averaging, allowing quantification of populated states in solution.[24] Computational modeling complements these experiments by mapping energy landscapes, with the Merck Molecular Force Field (MMFF) widely employed for its accuracy in predicting conformer geometries and relative energies in hydrocarbons, often achieving errors below 1 kcal/mol when benchmarked against quantum mechanical data.[25] External factors significantly modulate these preferences. Solvent effects arise from differential solvation of polar or hydrophobic surfaces, shifting equilibria toward more extended conformations in polar media like water versus compact ones in nonpolar solvents like chloroform.[26] Temperature influences conformer populations via Boltzmann distribution, accelerating interconversions and favoring higher-entropy forms at elevated temperatures.[27] Substituent positions introduce additional steric or electronic biases, with groups like methyl at 1,5-positions in medium rings exacerbating transannular strain and locking preferred geometries.[21]Stereochemical Aspects

Macrocycles exhibit diverse forms of stereoisomerism, broadly categorized into configurational and conformational types. Configurational stereoisomerism arises from fixed geometric arrangements, such as cis-trans (or Z-E) isomerism in unsaturated macrocycles containing double bonds. For instance, ring-closing metathesis reactions often yield mixtures of E and Z isomers in macrocyclic alkenes, as seen in the synthesis of secosteroidal macrocycles where an 8:2 E:Z ratio was obtained with 65% yield.[28] In contrast, conformational stereoisomerism stems from restricted rotations leading to stable isomers, exemplified by atropisomers in biaryl-containing macrocycles. These atropisomers, such as those in vancomycin aglycon models, result from hindered rotation around biaryl bonds, enabling isolation of single atropisomers with high atroposelectivity (94% yield for the R-configured precursor).[28][29] Helical chirality in macrocycles manifests as a non-superimposable mirror image due to the twisting of the ring structure, often observed in peptide-based and allene-incorporated systems. In peptide macrocycles, stapling techniques can stabilize α-helical conformations with defined handedness, as demonstrated in mixed-stereochemistry macrocyclic N-caps that enhance helix stability through rigid constraints.[30] Allenes contribute to helical chirality when embedded in macrocycles, where the cumulative double bonds impose orthogonal geometry and axial asymmetry, leading to stable helical architectures; for example, alleno-acetylenic macrocycles exhibit pronounced chiroptical properties due to this helical arrangement. Resolution of these helical enantiomers is commonly achieved via chiral high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), which separates based on differential interactions with chiral stationary phases, as applied to enantiopure allene-containing macrocycles.[31] Planar chirality in macrocycles, prevalent in calixarenes and substituted pillararenes, results from asymmetric substitution patterns that break the plane of symmetry; for instance, A1/A2-disubstituted pillar[32]arenes exhibit planar chirality with racemization barriers around 26 kcal/mol in nonpolar solvents like n-hexane at 298 K, enabling enantiomeric stability under certain conditions.[33] These barriers are influenced by solvent polarity and steric bulk, with higher values preventing rapid interconversion.[34] Stereochemical features of macrocycles are characterized using techniques like circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography. CD spectroscopy detects chiral asymmetries by measuring differential absorption of circularly polarized light, revealing helical or axial handedness; for example, enantiomeric Tröger's base macrocycles show mirror-image CD spectra in the UV region, confirming absolute configurations when correlated with density functional theory simulations.[35] X-ray crystallography provides direct visualization of atomic arrangements to assign absolute configurations, as in the case of chiral macrocyclic dilactams where crystal structures resolved the stereocenters based on known reference configurations.[36] These methods complement each other, with CD offering solution-phase insights and X-ray ensuring solid-state precision.Synthesis

General Methods

The synthesis of macrocycles often relies on the high-dilution principle, which promotes intramolecular cyclization over intermolecular polymerization by conducting reactions at low precursor concentrations, typically below 0.01 M, to statistically favor the formation of the desired ring.[28] This approach, first demonstrated by Paul Ruggli in 1912 for the cyclization of acyclic precursors into large rings and further developed by Karl Ziegler in 1933 using high-dilution techniques with methods such as acyloin condensation and Dieckmann cyclization, addresses the entropic disadvantage of bringing distant functional groups together in solution. The mathematical basis stems from kinetic considerations: the rate of intramolecular reaction is first-order (proportional to monomer concentration), while intermolecular reactions are second-order (proportional to the square of concentration), making cyclization dominant at low dilutions.[28] For ring size feasibility, Baldwin's rules provide guidance on preferred geometries for closures, favoring exo-trig modes for rings larger than seven members to minimize strain during nucleophilic or electrophilic attacks. Template-directed synthesis enhances efficiency by preorganizing linear precursors around a central scaffold, such as metal ions or solvents, to position reactive groups for cyclization and reduce the effective dimensionality of the reaction space.[28] A seminal example is Charles J. Pedersen's 1967 synthesis of crown ethers, where alkali metal cations like potassium served as templates to coordinate diol precursors during Williamson ether formation, yielding dibenzo-18-crown-6 in high selectivity due to the ion's stabilizing pseudocavity.[14] This method has been foundational for supramolecular macrocycles, as the template enforces proximity and orientation, often increasing yields by orders of magnitude compared to untemplated conditions. Classical reactions for macrocycle construction include the Dieckmann condensation, an intramolecular Claisen-type reaction of diesters to form cyclic β-keto esters, typically under basic conditions and high dilution for rings of 9–16 members, as exemplified in early syntheses of muscone analogs where sodium ethoxide facilitated closure of long-chain adipate derivatives.[28] Similarly, olefin metathesis emerged in the 1990s as a versatile tool for carbon-carbon bond formation in macrocycles; early applications using molybdenum-based catalysts, such as Grubbs' 1995 ring-closing metathesis of diene substrates to afford unsaturated 12–20 membered rings in natural product precursors, demonstrated its tolerance for functional groups and mild conditions, though initial yields were modest (20–50%) without optimization. Despite these advances, challenges in general macrocycle synthesis persist, particularly in yield optimization, where even high-dilution conditions can produce oligomeric byproducts requiring careful control of reaction parameters like temperature and solvent to achieve 30–70% cyclic product formation.[28] Purification often involves column chromatography to separate cyclic monomers from dimers and polymers based on differences in polarity and solubility, a labor-intensive step that underscores the need for scalable techniques in classical approaches.[37]Advanced Techniques and Stereocontrol

Ring-closing metathesis (RCM) using Grubbs catalysts has emerged as a powerful catalytic method for constructing macrocycles, enabling efficient formation of cyclic alkenes with high stereoselectivity. Developed by Grubbs and colleagues, second-generation ruthenium catalysts facilitate the cyclization of diene precursors under mild conditions, often achieving E/Z selectivity influenced by ring size and substituents.[38] For instance, in the synthesis of macrocyclic natural products, catalyst-controlled RCM allows stereoselective installation of trans-alkenes in medium to large rings, minimizing oligomerization side products.[39] Post-2015 advances include latent sulfur-chelated ruthenium iodide benzylidenes, which enhance substrate selectivity for large macrocycles (>14 members) by suppressing intermolecular metathesis, yielding up to 90% isolated products in drug discovery contexts.[40] Enyne metathesis represents a complementary catalytic approach for synthesizing unsaturated macrocycles, particularly those containing 1,3-diene motifs. Catalyzed by ruthenium or molybdenum complexes, this reaction couples alkynes and alkenes intramolecularly, producing cyclic enynes or dienes with defined geometry. Recent progress since 2015 emphasizes relay enyne metathesis in green solvents and under microwave conditions, improving yields for complex polycyclic systems derived from natural products.[41] These methods have been applied in total syntheses, such as terpenoids, where the metathesis step establishes key stereocenters through subsequent transformations.[42] Stereocontrol in macrocycle synthesis often employs chiral auxiliaries or asymmetric catalysis to dictate configuration at remote centers prior to cyclization. Chiral auxiliaries, such as oxazolidinones, direct stereoselective aldol or alkylation reactions in linear precursors, ensuring facial selectivity during ring closure. Asymmetric catalysis, exemplified by Sharpless epoxidation of allylic alcohols, generates epoxy alcohols as versatile building blocks for macrocyclic frameworks, with enantiomeric excesses exceeding 95% in natural product syntheses like polyketides.[43] Dynamic kinetic resolution (DKR) further advances stereocontrol by racemizing substrates in situ while selectively cyclizing one enantiomer, enabling access to enantioenriched macrocycles. Chemoenzymatic DKR using lipases and ruthenium racemization catalysts forms macrolactones from secondary alcohols with >99% ee, as demonstrated in depsipeptide analogs.[44] Organocatalytic DKR variants, such as N-heterocyclic carbene-mediated resolutions, target inherently chiral macrocycles by alkylating interconverting conformers, achieving up to 92% ee in 12-16 membered rings.[45] Innovations from 2020 to 2025 have integrated templating and computational tools to enhance macrocycle synthesis. DNA-templated synthesis leverages oligonucleotide scaffolds to preorganize building blocks, facilitating high-yield cyclizations via proximity effects; second-generation libraries incorporate diverse macrocyclization linkers like disulfides, yielding cyclic peptides with improved binding affinities for protein targets.[46] Photochemical cyclizations, such as Norrish-Yang reactions, enable mild, stereoselective formation of cyclobutane-fused macrocycles in terpenoid frameworks, with recent applications achieving >80% diastereoselectivity under visible light.[47] AI-assisted design employs machine learning, such as the Macformer model, to predict the success of macrocyclization reactions by analyzing precursor structures and conformational factors, achieving high accuracy in guiding synthesis of macrocyclic candidates.[8] A notable case study is the synthesis of neopeltolide, a marine macrolide, where RCM with Grubbs second-generation catalyst closes a 14-membered ring with trans-stereocontrol at the C12-C13 alkene, guided by chiral auxiliaries in precursor assembly; this step proceeded in 75% yield, enabling evaluation of antitumor activity.[48] Similarly, the total synthesis of periplanone B, a cockroach pheromone, utilized enzymatic kinetic resolution of acetylenic alcohols with lipases to establish chirality at C3 and C11, followed by anionic oxy-Cope rearrangement for ring expansion, affording the germacrane skeleton in enantiopure form.[49]Reactivity

Conformational Effects on Reactivity

In macrocycles, the Curtin-Hammett principle governs reactivity when conformers interconvert rapidly relative to the reaction timescale, such that the product ratio reflects the difference in transition-state free energies rather than ground-state populations. This dynamic equilibrium is particularly relevant in systems with low barriers to rotation or inversion, allowing minor conformers to contribute disproportionately if their transition states are lower in energy. For instance, in aziridine-containing 12-membered cyclic tetrapeptides, the N-acyl aziridine amide exhibits a low rotational barrier of 2.84–3.94 kcal/mol, enabling fast equilibration between cis and trans conformers; the cis form, favored under ring strain, directs regioselective nucleophilic attack at the α-carbon with >20:1 selectivity, as the transition state for this pathway benefits from reduced steric hindrance.[50] Transannular strain in medium-sized rings (8–11 members) further modulates reactivity by constraining functional group accessibility and promoting intramolecular interactions. This strain arises from non-bonded repulsions across the ring, elevating ground-state energy and lowering activation barriers for reactions that relieve it, such as transannular cyclizations or nucleophilic additions. In crown ethers like 18-crown-6, the flexible yet preorganized conformation optimizes cation coordination (e.g., K⁺ with micromolar affinity in methanol), which desolvates and activates counteranions, enhancing their nucleophilicity in phase-transfer catalysis. Spectroscopic methods, including infrared (IR) and Raman spectroscopy, offer direct evidence for assigning reactive conformers by probing vibrational modes sensitive to ring geometry and strain. Carbonyl stretching frequencies in IR spectra, for instance, shift between cis and trans amide conformers in strained macrocycles, correlating with their differing reactivities toward nucleophiles; Raman spectra complement this by highlighting symmetric ring deformations indicative of transannular interactions. These techniques have identified low-energy conformers in medium-ring diphosphines that predispose them to transannular bond formation. Quantitative assessments reveal that activation energy differences between pathways from preferred versus minor conformers typically span 2–5 kcal/mol, dictating selectivity under Curtin-Hammett conditions; such modest gaps can shift equilibrium populations by factors of 10–100 at room temperature, amplifying the influence of the more reactive species. In computational studies of macrocyclic peptides, these differences arise from torsional and transannular contributions, directly impacting reaction rates without exceeding 5 kcal/mol in most flexible systems.Peripheral Attack Model

The peripheral attack model, introduced by W. Clark Still and Igor Galynker in the early 1980s, serves as a predictive tool for stereoselectivity in nucleophilic reactions involving macrocyclic compounds, particularly those with medium-sized rings (8–14 atoms). The model rationalizes that nucleophiles preferentially approach from the less hindered, convex periphery of the macrocycle rather than the more sterically congested concave face, driven by the ring's preferred low-energy conformations. This framework emphasizes the role of transannular steric interactions in dictating face selectivity during bond formation.[51] Central to the model are conformational analyses that map the macrocycle's equilibrium structures to distinguish convex and concave faces, often facilitated by sp²-hybridized centers adopting quasi-planar geometries to minimize strain. It has proven particularly useful for forecasting outcomes in aldol additions, where enolates attack carbonyls, and Michael additions to α,β-unsaturated enones embedded in the ring, enabling remote asymmetric induction with high diastereoselectivity in rigidified systems. Representative examples include stereocontrolled conjugate additions in 10- to 12-membered lactones, yielding products with predictable axial or equatorial substitution patterns.[51] The model's predictions have been substantiated through experimental demonstrations of stereoselective nucleophilic additions. Computational validation, including density functional theory (DFT) calculations, supports these observations by confirming that low-energy conformers exhibit the anticipated face differentiation; for instance, DFT optimizations of 10-membered lactone conformers align with experimental stereoselectivity in peripheral nucleophilic approaches.[52] Despite its utility, the peripheral attack model has limitations, particularly in highly flexible macrocycles exceeding 20 atoms, where rapid conformational interconversions diminish reliable face discrimination and reduce predictive accuracy to moderate levels (typically 60–80% success in literature benchmarks). Post-2010 computational studies have addressed some shortcomings by incorporating solvation effects via implicit solvent models in molecular dynamics simulations, enhancing the model's applicability to solution-phase reactions.[53]Natural Occurrence

In Natural Products

Macrocycles are abundant in natural products, particularly among polyketide-derived compounds isolated from microbial sources, where they often exhibit antibiotic properties. A prominent class includes macrolide antibiotics, such as erythromycin, which features a 14-membered macrocyclic lactone ring and was isolated from the soil bacterium Streptomyces erythreus.[54] Another key example is the depsipeptide valinomycin, a 36-membered macrocycle produced by Streptomyces species that functions as a potassium-selective ionophore, highlighting the diversity in ester-amide linkages within these structures.[55] Natural macrocycles are sourced from diverse organisms, including marine invertebrates and microorganisms. From marine environments, neopeltolide, a 14-membered macrolide with cytotoxic activity, was isolated from deep-water lithistid sponges of the family Neopeltidae collected off the coast of Jamaica.[56] Microbial sources dominate, with many macrolides and depsipeptides derived from actinomycetes such as Streptomyces, underscoring bacteria as prolific producers of structurally complex macrocycles. Structural diversity in natural macrocycles encompasses various motifs, including polyene systems in antifungal agents. Amphotericin B, a 38-membered polyene macrolide isolated from Streptomyces nodosus, exemplifies this motif with its conjugated heptaene chain integrated into the ring, contributing to its broad-spectrum activity against fungal pathogens.[57] Recent isolations from 2020 onward have expanded this diversity, including nitrogen-containing macrocycles like the cyclic depsipeptide teixobactin analogs from uncultured soil bacteria, though natural macrocyclic arenes remain rare and often synthetic mimics of bacterial scaffolds.[58] Biosynthesis of many natural macrocycles relies on polyketide synthases (PKS), multifunctional enzyme assemblies that iteratively build carbon chains before cyclization. In macrolide production, modular type I PKS systems, such as the erythromycin gene cluster (ery), facilitate ring closure via thioesterase domains, with gene cluster analysis revealing conserved modules for chain extension and modification.[59] This pathway, prevalent in bacterial genomes, enables the structural variety observed in isolated macrocycles through variations in PKS domain architecture and post-cyclization tailoring.Biological Roles

Macrocycles play critical roles in biological ion transport, particularly through natural ionophores that facilitate selective movement of cations across membranes. Valinomycin, a macrocyclic depsipeptide produced by Streptomyces species, exemplifies this function by forming a rigid cavity that coordinates potassium ions (K⁺) with high specificity, achieving a selectivity ratio of approximately 10,000:1 over sodium ions (Na⁺). This enables valinomycin to shuttle K⁺ across lipid bilayers, disrupting electrochemical gradients in bacterial and mitochondrial membranes, which contributes to its antibiotic activity by uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation.[60] Similarly, nonactin, another macrocyclic ionophore from Streptomyces, binds K⁺ in a cage-like structure, promoting electroneutral transport and aiding in cellular homeostasis under stress conditions.[61] In antibiotic mechanisms, macrocycles often target essential cellular processes, including protein synthesis inhibition and membrane disruption. Macrolide antibiotics such as clarithromycin bind to the 50S subunit of the bacterial ribosome, specifically at the peptidyl transferase center, blocking the translocation step of translation and halting polypeptide chain elongation. This selective inhibition spares eukaryotic ribosomes due to structural differences, making macrolides effective against Gram-positive pathogens.[62] For membrane disruption, polyene macrolides like amphotericin B interact with ergosterol in fungal membranes, forming barrel-shaped pores that allow ion leakage and cell lysis, a mechanism that underscores their role in innate defense against fungal infections.[63] Macrocycles also mediate signaling in microbial communities, notably through cyclic peptides involved in quorum sensing. In Gram-positive bacteria, autoinducing peptides (AIPs) such as the thiolactone-based signals in Staphylococcus aureus form cyclic structures that bind receptor histidine kinases, triggering gene expression for virulence factors and biofilm formation at high population densities. These macrocyclic signals enable coordinated behaviors like competence induction in Bacillus subtilis, where cyclic peptides regulate sporulation and DNA uptake.[64] Recent studies have highlighted macrocyclic polyamines in DNA regulation, where synthetic and natural variants like cyclen derivatives modulate chromatin structure and gene expression by binding DNA grooves, influencing epigenetic processes in eukaryotic cells as observed in 2023 investigations on polyamine assembly transitions.[65] From an evolutionary perspective, macrocycles are prevalent in secondary metabolites as defense mechanisms, having diverged to counter biotic pressures like herbivory and microbial competition. Macrocyclic pyrrolizidine alkaloids in plants such as Senecio species have evolved through frequent gain and loss events, providing toxicity against herbivores via hepatotoxic effects while deterring pathogens. This prevalence reflects adaptive advantages in ecological niches, where macrocyclic structures enhance stability and bioavailability for interspecies defense.[66] Overall, such roles underscore the evolutionary selection for macrocycles in maintaining cellular integrity and community dynamics.[67]Applications

In Supramolecular Chemistry

In supramolecular chemistry, macrocycles serve as versatile hosts for non-covalent assemblies, enabling selective molecular recognition and self-assembly through specific interactions such as ion-dipole coordination, hydrophobic effects, and π-stacking. Crown ethers exemplify this role in host-guest chemistry, where their cyclic polyether structures coordinate alkali metal cations via oxygen lone pairs aligning with the guest's electrostatic field. The seminal discovery of crown ethers by Charles J. Pedersen in 1967 introduced compounds like dibenzo-18-crown-6, which demonstrated remarkable selectivity for potassium ions (K⁺) due to a cavity size matching the ionic radius of approximately 1.33 Å. For instance, 18-crown-6 forms a stable 1:1 complex with K⁺ in methanol, exhibiting an association constant with log K ≈ 6.0, reflecting strong enthalpic contributions from multiple ion-oxygen interactions.[68] Beyond ionic guests, macrocycles like calixarenes facilitate molecular recognition of neutral molecules through their chalice-shaped cavities, which provide hydrophobic environments for encapsulation. Calix[69]arenes and higher homologs, first systematically explored by Gutsche in the 1980s, bind neutral aromatic or aliphatic guests via van der Waals forces and CH-π interactions, often achieving association constants in the range of 10²–10⁴ M⁻¹ in organic solvents. For example, p-tert-butylcalix[69]arene selectively accommodates neutral guests like toluene in its lower rim, demonstrating size and shape complementarity that stabilizes the complex without covalent bonds. Complementing this, pillararenes—rigid, pillar-shaped macrocycles introduced by Ogoshi et al. in 2008—excel in recognizing linear alkanes through their electron-rich π-cavity, promoting CH-π and hydrophobic interactions. Pillar[32]arenes, in particular, form pseudorotaxane-like complexes with n-alkanes such as n-hexane, with binding affinities enhanced by the planar arrangement of benzene units facilitating parallel π-stacking alignments. Macrocycles also drive self-assembly into topologically complex structures like rotaxanes and catenanes, where templating directs the interlocked architecture. In rotaxanes, a macrocyclic ring threads onto a linear axle, often stabilized by hydrogen bonding or donor-acceptor interactions; crown ethers such as 1,5-naphtho-24-crown-8 serve as wheels in J. Fraser Stoddart's templated syntheses, where π-donor-acceptor stacking between the crown and a paraquat axle yields yields up to 70% under kinetic control. Catenanes, featuring interlocked rings, emerge similarly, with early examples using crown ethers as one ring and metal coordination for the second, as pioneered by Sauvage, but Stoddart's group advanced organic templates, achieving catenated yields exceeding 50% via clipping strategies. These assemblies rely on the macrocycle's preorganization to lower the entropic penalty of threading, enabling precise control over mechanical bonding. Such host-guest and self-assembly principles underpin practical applications, including ion sensors and molecular machines. Crown ether-based sensors exploit binding-induced changes in fluorescence or electrochemical signals for selective ion detection; for example, 18-crown-6 derivatives in optical sensors achieve micromolar sensitivity for K⁺ via chelation-enhanced quenching, with selectivity ratios over 10³ relative to Na⁺. In molecular machines, Stoddart's bistable rotaxanes function as switches, where redox or pH stimuli shuttle the macrocyclic component along the axle, mimicking muscle-like contraction with energies on the order of 10–20 kJ/mol per cycle, as demonstrated in [70]rotaxane systems incorporating tetrathiafulvalene and cyclophane units. These developments highlight macrocycles' role in constructing responsive supramolecular devices for materials science and nanotechnology.In Drug Discovery

Macrocycles have emerged as promising therapeutic agents in drug discovery due to their unique structural properties that address limitations of traditional small molecules and linear peptides. Their rigid scaffolds confer resistance to protease degradation, thereby improving metabolic stability and extending half-life in vivo.[5] This rigidity also enables macrocycles to present a large, conformationally constrained surface area for binding, facilitating interactions with extended or groove-like protein interfaces that are often undruggable by conventional ligands.[71] Notably, certain macrocycles exceed 500 Da yet achieve oral bioavailability rates of 30–40%, as seen in approved drugs, thus broadening their applicability beyond injectable formats.[5] Despite these benefits, macrocycles face significant challenges, particularly in achieving adequate bioavailability stemming from their size, polarity, and conformational flexibility. Poor membrane permeability often limits systemic exposure, necessitating innovative chemical modifications. One established strategy involves N-methylation of amide bonds to reduce hydrogen bonding potential and enhance lipophilicity, as demonstrated in cyclosporine A, a calcineurin inhibitor used for immunosuppression that relies on multiple N-methyl groups for its oral absorption.[71] Such approaches have been pivotal in overcoming these hurdles while preserving biological activity. FDA-approved macrocyclic drugs underscore their clinical viability across diverse therapeutic areas. Macrolide antibiotics, such as azithromycin, feature a 15-membered lactone ring and inhibit bacterial protein synthesis, providing broad-spectrum treatment for infections like pneumonia and sexually transmitted diseases. Recent approvals from 2020–2025 include voclosporin (2021), a non-immunosuppressive analog of cyclosporine for lupus nephritis that modulates calcineurin activity with reduced toxicity, and rezfungin (2023), a novel echinocandin macrocycle for invasive candidiasis that offers once-weekly dosing due to its long half-life.[72] These examples illustrate macrocycles' role in addressing unmet needs in infectious diseases and autoimmune disorders. Design and optimization of macrocyclic therapeutics rely on advanced tools to navigate their synthetic complexity. Combinatorial libraries, generated via split-pool synthesis or DNA-encoded approaches, enable rapid exploration of structural diversity, yielding hits against targets like kinases and proteases.[73] Complementary structure-activity relationship (SAR) analyses then refine these leads, often resulting in potency gains of up to 100-fold compared to linear precursors by fine-tuning ring size, substituents, and stereochemistry.[71]Emerging Applications

Recent advancements in macrocycle research have expanded their utility into innovative areas such as bioimaging, catalysis, materials science, and therapeutic design, leveraging their unique structural rigidity and host-guest properties. Fluorescent macrocycles, particularly those incorporating nitrogen-containing arene units, have emerged as promising probes for bioimaging applications due to their tunable photophysical properties and biocompatibility. These compounds enable high-resolution visualization of cellular processes, with synthesis often achieved through dynamic imine exchange reactions that allow for modular assembly and functional group diversification. For instance, a 2025 review highlights examples where nitrogen-rich macrocyclic arenes exhibit enhanced fluorescence quantum yields (>0.5) and selectivity for biomolecular targets in live-cell imaging. In catalysis, macrocyclic ligands are increasingly employed to facilitate enantioselective reactions, providing precise control over stereochemistry in complex transformations. Recent developments include the use of chiral macrocyclophanes and pillararene derivatives as ligands in asymmetric cross-coupling reactions, achieving enantiomeric excesses exceeding 95% for the synthesis of planar-chiral frameworks.[74] Polyamine-based macrocycles have also shown potential in CO2 capture, where their cyclic architecture enhances adsorption capacity under humid conditions. These applications underscore macrocycles' role in sustainable catalysis and carbon mitigation strategies. Within materials science, pillararene-based polymers have been integrated into nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery, exploiting their supramolecular assembly to achieve stimuli-responsive release in tumor microenvironments. These systems demonstrate encapsulation efficiencies of over 80% for hydrophobic therapeutics, improving bioavailability and reducing off-target effects in cancer models. Complementing this, macrocycle-derived sensors for ion detection have advanced environmental and biomedical monitoring, with fluorescent pillararene probes offering detection limits in the nanomolar range for heavy metal ions like mercury and lead. Such sensors leverage macrocyclic cavities for selective binding, enabling real-time fluorescence-based assays.[75][76] Emerging trends in macrocycle design incorporate artificial intelligence to optimize structures for sustainability, accelerating the discovery of eco-friendly variants with reduced synthetic footprints. In peptide therapeutics, macrocyclic variants have progressed toward cancer treatment, with AI-guided designs yielding potent inhibitors targeting cancer-related proteins such as KRAS.[77] These innovations position macrocycles at the forefront of next-generation, multifunctional materials and therapeutics.References

- Macrocycles usually reside in the beyond the Rule of 5 chemical space, but 30–40% of the drugs and clinical candidates are orally bioavailable.

- Oct 2, 2023 · Macrocyclic compounds in the solid state can encapsulate guests with larger affinities than their soluble counterparts. This is crucial for use in applications ...

- Macrocyclic compounds occupy an important chemical space between small molecules and biologics and are prevalent in many natural products and pharmaceuticals.