Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

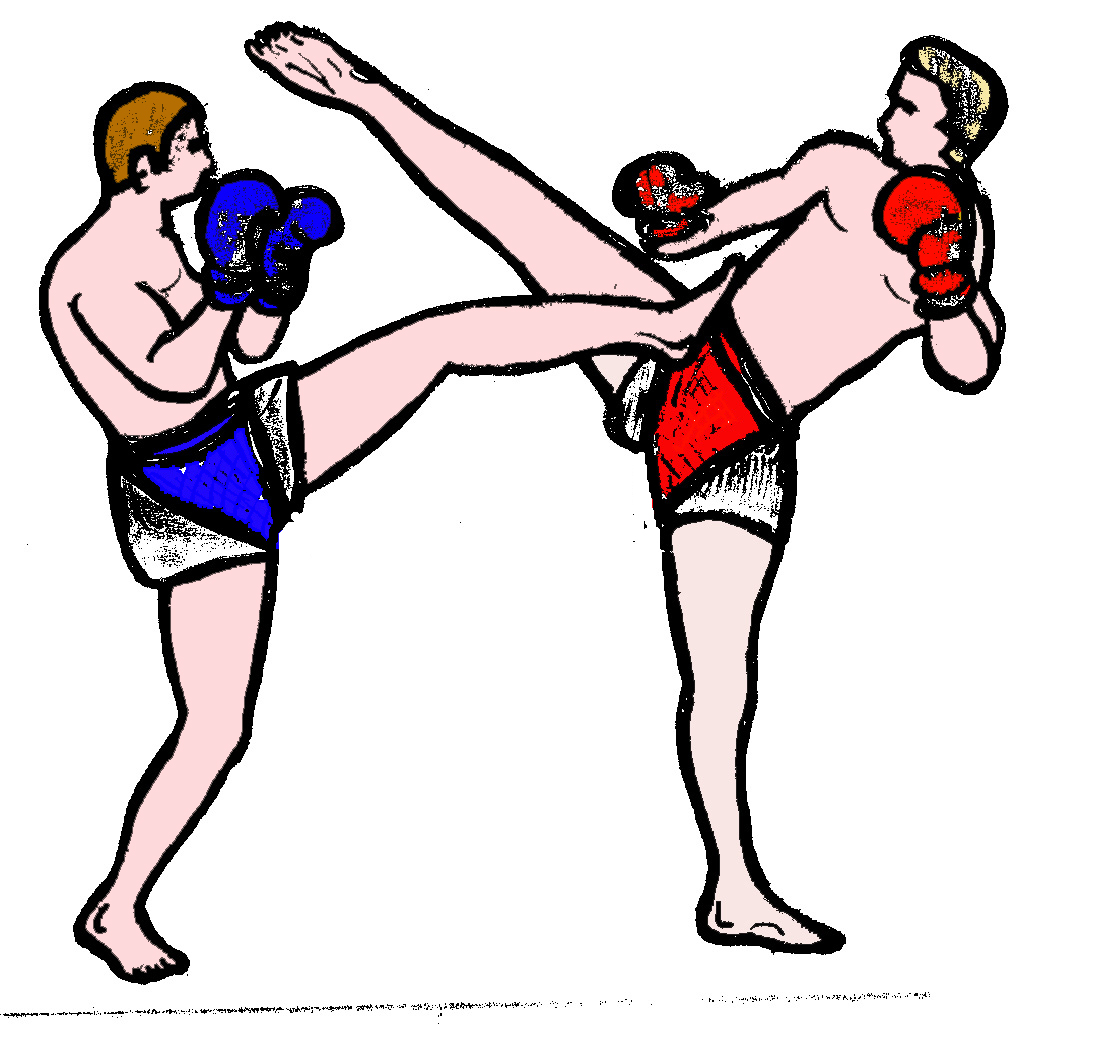

Front kick

View on Wikipedia| Front kick | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A counter-attack with a front kick in burmese boxing | |||||||

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 앞차기 | ||||||

| Hanja | none | ||||||

| |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 前蹴り | ||||||

| Hiragana | まえげり | ||||||

| |||||||

The front kick in martial arts is a kick executed by lifting the knee straight forward, while keeping the foot and shin either hanging freely or pulled to the hip, and then straightening the leg in front of the practitioner and striking the target area. It is desirable to retract the leg immediately after delivering the kick, to avoid the opponent trying to grapple the leg and (unless a combination is in process) to return to stable fighting stance.

The front kick described is the typical basic front kick of karate or taekwondo. But the front kick can also be defined more broadly as a straight forward kick directly to the front, and then include several variations from many different styles. A front kick can be delivered forward in a penetrating way (hip thrust), or upwards to attack the head.

Details of the technique

[edit]

In martial arts implying either barefooted combat or very light footwear, the strike is usually delivered by using the ball of the foot (while pointing the foot toward the target area and keeping toes up to prevent injury) or by heel. When heavier footwear is used, there is an option to use the whole sole as a striking surface. It is also possible to kick with the top of the foot (the instep) in cases of striking at the groin or under the arm which can be very damaging.

Using the ball of a foot is preferred in karate. This method demands more control of one's movement, but allows for a narrow, penetrating strike. Taekwondo practitioners utilise both heel and ball of the foot for striking. It is common to perform tempering exercises to strengthen the ball of the foot, as many new practitioners are unable to exercise full-power front kicks on training gear, such as a body bag.

With specific techniques and in certain styles, the impact point of the front kick can be more exotic. Certain Japanese styles have a front kick generally used as a stop-kick where the blade of the foot is used to connect, like for a side kick (the foot blade front kick). The heel is often used straight (mae kakato geri) or with the foot tilted (tilted heel front kick), especially in stop-kicks, close kicks or high front kicks. Japanese ninjutsu has variations using the straightened and hardened toes. Front kicks to the groin (kin geri) like the lift kick or the upward front kick (mae geri keage), use the top of the foot. The phantom groin kick uses the whole of the inside of the foot to connect very effectively. Stop kicks often use the whole plant of the foot to push away the opponent.[1]

Various combat systems teach "general" front kicks using the heel or whole foot when footwear is on. For example, martial art systems employed by militaries assume that a fighter wears heavy footwear, is generally less mobile than typically assumed in competition martial arts, and may have their leg muscles severely fatigued. Properly executing a fast "snap" front kick while controlling one's foot direction may be difficult in said conditions. Less technically demanding kicks utilizing the soles of heavy footwear as a striking surface are easier to execute.

The front kick is typically performed with a straight and balanced upper body, but it allows for variety in motion of hips and body overall. Martial arts systems exploit this ability in different fashions. For example, a karateka may perform mae geri while standing upright, or lean somewhat back during the attack, intending to increase the reach of the kick. If a simple "kick-punch" combination is executed, this slight lean allows for more momentum placed into the movement of upper body, thus the karateka will end with a more powerful body movement behind the punch. The opposite situation is exploited in some variations of Wing Chun, where stiff forward motion of both hands blocking/striking in upper area could be accompanied with a slight leaning forward and simultaneous front kick into groin/thigh, etc. Hip movement may be used to increase the reach and to thrust one's leg into the target, resulting in a more powerful strike (a common practice in taekwondo and some styles of karate).

Applications and counters

[edit]Front kicks are typically aimed at targets below the chest: stomach, thighs, groin, knees or lower. Highly skilled martial artists are often capable of striking head-level targets with front kick (albeit rarely use it this way). The front kick is fast and involves little body motion betraying the technique's nature prior to execution. This makes a well-developed front kick an excellent asset in both offence and defense.

When defending, front kick could be used to severely damage the lower area of the opponent who has started an attack, but has overconcentrated on guarding head/upper body, and as a good tool to keep enemy from punch range. In offense, front kick could serve as an excellent opener for combination attacks, as it is fast, dangerous enough for opponent to switch attention to block/deflecting/evading the kick, but requires little deviation from the upright fighting stance, which is good to start punch attack from. Overall, there is a wide variety of situations where this kick could be exploited by a creative martial arts practitioner.

Common ways to counter a front kick are deflecting it with hand, shin, etc., stepping away/sideways, or, given the kick is visibly pointed into abdomen/thighs area, shifting a body so it passes along. The last method is somewhat risky, as it relies heavily on defender's agility, with a front kick being the fastest kick possible. More exotic techniques of countering front kicks exist, like one incorporated in Wado ryu kihon kumite (referred to as yakusoku, or prearranged, kumite, in some schools). Said technique involves simultaneously pushing opponents leg away from one's centerline and attacking the leg with a downward elbow strike into the hip. However, this method is not recommended to beginners and as a general purpose one.

Also, although well-executed front kick is very fast, a careless execution presents an opponent with excellent opportunity for grappling, which could be disastrous for an attacker. Once the leg is grappled, a variety of attacks is available to a defender, such as wrestling techniques resulting in pain compliance hold, immediate counterattack with punches, throws, kicks into lower area and combinations of all above. For this reason, 'recocking' the leg after the kick is truly important, especially in real-life situations, where rules common to many competition martial arts do not apply. However, executing front kicks to the waist and below is relatively safe and effective, given the leg is immediately retracted.

Cambodian style

[edit]

In the Cambodian martial arts of pradal serey and bokator the front kick is also used. The front kick is called sniet theak trang (push kick) or chrot eysei (sage push). The push kick is considered easy and simple to use in fights. The push kick can be used on areas that are not carefully guarded by the opponent. The push kick can be delivered by the ball of the foot or the heel of the foot. The push kick can be used to attack below the waist, the chest and the middle of the face.[2]

Karate

[edit]

The front kick, called mae geri in Japanese, is certainly the main kick in traditional karate of all styles. It is the most used kick in traditional kata forms and the most practiced kick in traditional kihon practice. The kick is a very strong and fast strike, and easier to master than less “natural” kicks. The kick generally connects with the ball of the foot, under the toes, but other points of impact are sometimes used in the many variants existing in Japanese karate and other styles. It can be thrusting (kekomi) or snapping (keage), or somewhere in between. In its thrusting or kekomi form the kicker pushes the foot into the target powerfully leveraging the momentum of his own body weight in order to propel the opponent or target backwards. In its snapping or keage form the kicker emphasizes the extremely quick retraction or recoil or re-chamber of the foot and the lower leg immediately after impact (thereby making it difficult to catch or grab the leg by the opponent); The keage kick exhibits less pushing force but more breaking impact than the kekomi form of the kick. It can be delivered with hopping (surikonde) or jumping (tobikonde), and sometimes with a straight leg all-the-way (mae keage). It can be executed with the front leg, defensively or hopping forward, or the rear leg. It can be executed with nearly square hips, or with hips lined sideways like the yoko geri of Wado-ryu Karate. There are many other variations, as the kick can also be feinted, angled or delivered from the ground.[3]

Tae Kwon Do

[edit]In taekwondo, the front kick bears the name ap chagi. It is distinct from the push kick (mireo chagi) in that the power should be delivered instantaneously. Since the leg moves forward while the shin and foot naturally swing upwards, the easiest application of this kick is that of directing one's energy upwards, perhaps considering it a "kick to the groin". However, one can deliver massive force forward with this kick as well, which is considered its main application by most instructors. Directed forward, this is actually one of the most powerful kicks in Taekwondo, and it is quite often used in exhibitions and board-breaking competitions where power is demonstrated.

In order to not injure ones toes while executing this kick, it is usually delivered through the front base of the foot (ap chook), if not with the flat upper side of the foot (bal deung). If performed with the bare foot then the ball of the foot is used on impact with the toes drawn up to prevent injury. To strike with ap chook one has to raise one's toes so that their tips will not be the first contact point. Even when directed forward, this is not a kick where the first contact point should be the base of the heel, as is considered beneficial in some other martial arts having a similar kick. In Taekwondo, one would strike forward with the ankle extended, so that the upper side of the foot forms a straight line with the shin, and with the toes bent back (pointing up). In other words, an "ap chook ap chagi". Having the foot in any other position when directing this kick strictly forward would be considered highly unorthodox, and is a common error among beginners.

In addition to being a kick in itself, the front kick is an exercise used by many instructors to teach the principle of lifting ones knee before the rest of the kick commences, something which is considered important in taekwondo, where it is somewhat literally translated from the Korean ap chagi (앞차기), (and many kicking arts with the notable exception of capoeira). In competition fights (known as "sparring" or "kyorugi") this kick sees little actual use, except possibly as a component in an improvised kick which is perhaps intended as an "an chagi" or "naeryo chagi".

It is common to slightly bend the knee of the leg one is standing on when executing this kick, and pointing the foot one is standing on somewhat outwards. As in all taekwondo kicks, one will also try to get ones "hip into the kick", resulting perhaps in a slight shift of weight forward. In any case, this is a linear kick, and as such one that one can get ones weight behind.

There exist countless variations of this kick, and it can be used along with other kicks without one having to put ones kicking foot down in between kicks. A very common variation is "ttwimyeo ap chagi", a flying front kick which can reach an impressive height.

Some instructors refer to this kick as the "flash kick". This is in tune with the line of thought which seems prevalent in the various taekwondo forms, where the ap chagi is used very extensively in combination with relatively short range hand strikes and blocks, mimicking situations in which it would have to be performed quite quickly.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ De Bremaeker, M. et al., The Essential Book of Martial Arts Kicks: 89 Kicks from Karate, Taekwondo, Muay Thai, Jeet Kune Do, and others (Tuttle Publishing, 2010), p. 23. ISBN 0-8048-4122-5

- ^ ស្នៀតធាក់ត្រង់ ឬច្រត់ ឥសី [Attack Techniques: Push Kick or Chrot Eysei]. (2019, December 17). Mee Chiet. Retrieved May 14, 2022, from https://www.meechiet.com.kh/kh/article/662

- ^ De Bremaeker, M. et al., The Essential Book of Martial Arts Kicks: 89 Kicks from Karate, Taekwondo, Muay Thai, Jeet Kune Do, and others (Tuttle Publishing, 2010), p. 25. ISBN 0-8048-4122-5

References

[edit]- Scott Shaw (2006). Advanced Taekwondo. Tuttle Publishing. p. 45. ISBN 0-8048-3786-4.

- Woo Jin Jung (1999). Freestyle Sparring. Jennifer Lawler. p. 22. ISBN 0-7360-0129-8.

- De Bremaeker, M.; et al. (2010). The Essential Book of Martial Arts Kicks: 89 Kicks from Karate, Taekwondo, Muay Thai, Jeet Kune Do, and others. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 11–57. ISBN 978-0-8048-4122-1.