Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fujian

View on WikipediaKey Information

| Fujian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Fujian" in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 福建 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Fukien | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Fu(zhou) and Jian(zhou)" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Abbreviation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 闽 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 閩 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | [the Min River] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Fujian[a] is a province in southeastern China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its capital is Fuzhou and its largest prefecture city by population is Quanzhou, with other notable cities including the port city of Xiamen and Zhangzhou. Fujian is located on the west coast of the Taiwan Strait as the closest province geographically and culturally to Taiwan. This is as a result of the Chinese Civil War. Additionally, a small portion of historical Fujian is administered by Taiwan, romanized as Fuchien.

While the population predominantly identifies as Han, it is one of China's most culturally and linguistically diverse provinces. The dialects of the language group Min Chinese are most commonly spoken within the province, including the Fuzhou dialect and Eastern Min of Northeastern Fujian province and various Southern Min and Hokkien dialects of southeastern Fujian. The capital city of Fuzhou and Fu'an of Ningde prefecture along with Cangnan county-level city of Wenzhou prefecture in Zhejiang province make up the Min Dong linguistic and cultural region of Northeastern Fujian. Hakka Chinese is also spoken in Fujian, by the Hakka people. Min dialects, Hakka, and Standard Chinese are mutually unintelligible. Due to emigration, much of the ethnic Chinese populations of Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines speak Southern Min (or Hokkien).

With a population of 41.5 million, Fujian ranks 15th in population among Chinese provinces. In 2022, its GDP reached CN¥5.31 trillion (US$790 billion by nominal GDP), ranking 4th in East China region and 8th nationwide in GDP.[6] Fujian's GDP per capita is above the national average, at CN¥126,829 (US$18,856 in nominal), the second highest GDP per capita of all Chinese provinces after Jiangsu.[6]

Fujian is considered one of China's leading provinces in education and research. As of 2023, two major cities in the province ranked in the top 45 cities in the world (Xiamen 38th and Fuzhou 45th) by scientific research output, as tracked by the Nature Index.[7]

Name

[edit]The name Fujian (福建) originated from the combination of the city names of Fuzhou (福州) and nearby Jianzhou (建州, or present-day Nanping (南平)).

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2024) |

Prehistoric Fujian

[edit]Recent archaeological discoveries in 2011 demonstrate that Fujian had entered the Neolithic Age by the middle of the 6th millennium BC.[8] From the Keqiutou site (7450–5590 BP), an early Neolithic site in Pingtan Island located about 70 kilometres (43 mi) southeast of Fuzhou, numerous tools made of stones, shells, bones, jades, and ceramics (including wheel-made ceramics) have been unearthed, together with spinning wheels, which is definitive evidence of weaving.

The Tanshishan (曇石山) site (5500–4000 BP) in suburban Fuzhou spans the Neolithic and Chalcolithic Age where semi-underground circular buildings were found in the lower level. The Huangtulun (黃土崙) site (c. 1325 BC), also in suburban Fuzhou, was of the Bronze Age in character.

Tianlong Jiao (2013)[9] notes that the Neolithic appeared on the coast of Fujian around 6,000 B.P. During the Neolithic, the coast of Fujian had a low population density, with the population depending on mostly on fishing and hunting, along with limited agriculture.

There were four major Neolithic cultures in coastal Fujian, with the earliest Neolithic cultures originating from the north in coastal Zhejiang.[9]

- Keqiutou culture (壳丘头文化; c. 6000 – c. 5500 BP, or c. 4050 – c. 3550 BC)

- Tanshishan culture (昙石山文化; c. 5000 – c. 4300 BP, or c. 3050 – c. 2350 BC)

- Damaoshan culture (大帽山文化; c. 5000 – c. 4300 BP)

- Huangguashan culture (黄瓜山文化; c. 4300 – c. 3500 BP, or c. 2350 – c. 1550 BC)

There were two major Neolithic cultures in inland Fujian, which were highly distinct from the coastal Fujian Neolithic cultures.[9] These are the Niubishan culture (牛鼻山文化) from 5000 to 4000 years ago, and the Hulushan culture (葫芦山文化) from 2050 to 1550 BC.

Minyue kingdom

[edit]

Fujian was also where the kingdom of Minyue was located. The word "Mǐnyuè" was derived by combining "Mǐn" (simplified Chinese: 闽; traditional Chinese: 閩; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: bân), which is perhaps an ethnic name (simplified Chinese: 蛮; traditional Chinese: 蠻; pinyin: mán; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: bân), and "Yuè", after the State of Yue, a Spring and Autumn period kingdom in Zhejiang to the north. This is because the royal family of Yuè fled to Fujian after its kingdom was annexed by the State of Chu in 306 BC. Mǐn is also the name of the main river in this area, but the ethnonym is probably older.

Qin dynasty

[edit]The Qin deposed the King of Minyue, establishing instead a paramilitary province there called Minzhong Commandery. Minyue was a de facto kingdom until one of the emperors of the Qin dynasty, the first unified imperial Chinese state, abolished its status.[10]

Han dynasty

[edit]In the aftermath of the Qin dynasty's fall, civil war broke out between two warlords, Xiang Yu and Liu Bang. The Minyue king Wuzhu sent his troops to fight with Liu and his gamble paid off. Liu was victorious and founded the Han dynasty. In 202 BC, he restored Minyue's status as a tributary independent kingdom. Thus Wuzhu was allowed to construct his fortified city in Fuzhou as well as a few locations in the Wuyi Mountains, which have been excavated in recent years. His kingdom extended beyond the borders of contemporary Fujian into eastern Guangdong, eastern Jiangxi, and southern Zhejiang.[11]

After Wuzhu's death, Minyue maintained its militant tradition and launched several expeditions against its neighboring kingdoms in Guangdong, Jiangxi, and Zhejiang, primarily in the 2nd century BC. This was stopped by the Han dynasty as it expanded southward. The Han emperor eventually decided to get rid of the potential threat by launching a military campaign against Minyue. Large forces approached Minyue simultaneously from four directions via land and sea in 111 BC. The rulers in Fuzhou surrendered to avoid a futile fight and destruction and the first kingdom in Fujian history came to an abrupt end.

Fujian was part of the much larger Yang Province (Yangzhou), whose provincial capital was designated in Liyang (歷陽; present-day He County, Anhui).

The Han dynasty collapsed at the end of the 2nd century AD, paving the way for the Three Kingdoms era. Sun Quan, the founder of the Kingdom of Wu, spent nearly 20 years subduing the Shan Yue people, the branch of the Yue living in mountains.

Jin era

[edit]The first wave of immigration of the noble class arrived in the province in the early 4th century when the Western Jin dynasty collapsed and the north was torn apart by civil wars and rebellions by tribal peoples from the north and west. These immigrants were primarily from eight families in central China: Chen (陈), Lin (林), Huang (黄), Zheng (郑), Zhan (詹), Qiu (邱), He (何), and Hu (胡). To this day, the first four remain the most popular surnames in Fujian.[citation needed]

Nevertheless, isolation from nearby areas owing to rugged terrain contributed to Fujian's relatively undeveloped economy and level of development, despite major population boosts from northern China during the "barbarian" rebellions. The population density in Fujian remained low compared to the rest of China. Only two commanderies and sixteen counties were established by the Western Jin dynasty. Like other southern provinces such as Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, and Yunnan, Fujian often served as a destination for exiled prisoners and dissidents at that time.

During the Southern and Northern Dynasties era, the Southern Dynasties (Liu Song, Southern Qi, Liang (Western Liang), and Chen) reigned south of the Yangtze River, including Fujian.

Sui and Tang dynasties

[edit]During the Sui and Tang eras a large influx of migrants settled in Fujian.[12][10]

During the Sui dynasty, Fujian was again part of Yang Province.

During the Tang, Fujian was part of the larger Jiangnan East Circuit, whose capital was at Suzhou. Modern-day Fujian was composed of around 5 prefectures and 25 counties.

The Tang dynasty (618–907) oversaw the next golden age of China, which contributed to a boom in Fujian's culture and economy. Fuzhou's economic and cultural institutions grew and developed. The later years of the Tang dynasty saw several political upheavals in the Chinese heartland, prompting even larger waves of northerners to immigrate to the northern part of Fujian.

Five Dynasties Ten Kingdoms

[edit]

As the Tang dynasty ended, China was torn apart in the period of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms. During this time, a second major wave of immigration arrived in the safe haven of Fujian, led by Wang Brothers (Wang Chao, Wang Shengui and Wang Shenzhi), who set up an independent Kingdom of Min with its capital in Fuzhou. After the death of the founding king, however, the kingdom suffered from internal strife, and was soon absorbed by Southern Tang, another southern kingdom.[13]

Parts of northern Fujian were conquered by the Wuyue Kingdom to the north as well, including the Min capital Fuzhou.

Quanzhou city was blooming into a seaport under the reign of the Min Kingdom.[citation needed][when?][14][15]

Qingyuan Jiedushi was a military/governance office created in 949 by Southern Tang's second emperor Li Jing for the warlord Liu Congxiao, who nominally submitted to him but controlled Quan (泉州, in modern Quanzhou, Fujian) and Zhang (漳州, in modern Zhangzhou, Fujian) Prefectures in de facto independence from the Southern Tang state.[16] (Zhang Prefecture was, at times during the circuit's existence, also known as Nan Prefecture (南州).)[17] Starting in 960, in addition to being nominally submissive to Southern Tang, Qingyuan Circuit was also nominally submissive to Song, which had itself become Southern Tang's nominal overlord.[18]

After Liu's death, the circuit was briefly ruled by his biological nephew/adoptive son Liu Shaozi, who was then overthrown by the officers Zhang Hansi and Chen Hongjin. Zhang then ruled the circuit briefly, before Chen deposed him and took over.[17] In 978, with Song's determination to unify Chinese lands in full order, Chen decided that he could not stay de facto independent, and offered the control of the circuit to Song's Emperor Taizong, ending Qingyuan Circuit as a de facto independent entity.[19]

Song dynasty

[edit]The area was reorganized into the Fujian Circuit in 985, which was the first time the name "Fujian" was used for an administrative region.[citation needed]

Vietnam

[edit]Many Chinese migrated from Fujian's major ports to Vietnam's Red River Delta. The settlers then created Trần port and Vân Đồn.[20] Fujian and Guangdong Chinese moved to the Vân Đồn coastal port to engage in commerce.[21]

During the Lý and Trần dynasties, many Chinese ethnic groups with the surname Trần (陳) migrated to Vietnam from what is now Fujian or Guangxi. They settled along the coast of Vietnam and the capital's southeastern area.[22] The Vietnamese Trần clan traces their ancestry to Trần Tự Minh (227 BC). He was a Qin General during the Warring state period who belonged to the indigenous Mân, a Baiyue ethnic group of Southern China and Northern Vietnam. Tự Minh also served under King An Dương Vương of Âu Lạc kingdom in resisting Qin's conquest of Âu Lạc. Their genealogy also included Trần Tự Viễn (582 – 637) of Giao Châu and Trần Tự An (1010 - 1077) of Đại Việt. Near the end of the 11th century the descendants of a fisherman named Trần Kinh, whose hometown was in Tức Mạc village in Đại Việt (Modern day Vietnam), would marry the royal Lý clan, which was then founded the Vietnam Tran dynasty in 1225.[23]

In Vietnam, the Trần served as officials. The surnames are found in the Trần and Lý dynasty Imperial exam records.[24] Chinese ethnic groups are recorded in Trần and Lý dynasty records of officials.[25] Clothing, food, and languages were fused with the local Vietnamese in Vân Đồn district where the Chinese ethnic groups had moved after leaving their home province of what is now Fujian, Guangxi, and Guangdong.

In 1172, Fujian was attacked by Pi-she-ye pirates from Taiwan or the Visayas, Philippines.[26]

Yuan dynasty

[edit]After the establishment of the Yuan dynasty, Fujian became part of Jiangzhe province, whose capital was at Hangzhou. From 1357 to 1366 Muslims in Quanzhou participated in the Ispah Rebellion, advancing northward and even capturing Putian and Fuzhou before the rebellion was crushed by the Yuan. Afterward, Quanzhou city lost foreign interest in trading and its formerly welcoming international image as the foreigners were all massacred or deported.

Yuan dynasty General Chen Youding, who had put down the Ispah Rebellion, continued to rule over the Fujian area even after the outbreak of the Red Turban Rebellion. Forces loyal to the eventual Ming dynasty founder Zhu Yuanzhang (Hongwu Emperor) defeated Chen in 1367.[27]

Ming dynasty

[edit]After the establishment of the Ming dynasty, Fujian became a province, with its capital at Fuzhou. In the early Ming era, Fuzhou Changle was the staging area and supply depot of Zheng He's naval expeditions. Further development was severely hampered by the sea trade ban, and the area was superseded by nearby ports of Guangzhou, Hangzhou, Ningbo and Shanghai despite the lifting of the ban in 1550.[citation needed] Large-scale piracy by Wokou was eventually wiped out by the Chinese military.

An account of the Ming dynasty Fujian was written by No In (Lu Ren 鲁认).[28][29]

The Pisheya appear in Quanzhou Ming era records.[30]

Qing dynasty

[edit]The late Ming and early Qing dynasty symbolized an era of a large influx of refugees and another 20 years of sea trade ban under the Kangxi Emperor, a measure intended to counter the refuge Ming government of Koxinga in the island of Taiwan.

The sea ban implemented by the Qing forced many people to evacuate the coast to deprive Koxinga's Ming loyalists of resources. This has led to the myth that it was because Manchus were "afraid of water".

Incoming refugees did not translate into a major labor force, owing to their re-migration into prosperous regions of Guangdong. In 1683, the Qing dynasty conquered Taiwan in the Battle of Penghu and annexed it into Fujian province, as Taiwan Prefecture. Many more Han Chinese then settled in Taiwan. Today, most Taiwanese are descendants of Hokkien people from Southern Fujian. Fujian and Taiwan were originally treated as one province (Fujian-Taiwan-Province), but starting in 1885, they split into two separate provinces.[31]

In the 1890s, the Qing ceded Taiwan to Japan via the Treaty of Shimonoseki after the First Sino-Japanese War. In 1905–1907 Japan made overtures to enlarge its sphere of influence to include Fujian. Japan was trying to obtain French loans and also avoid the Open Door Policy. Paris provided loans on condition that Japan respects the Open Door principles and does not violate China's territorial integrity.[32]

Republic of China

[edit]

The Xinhai revolution overthrew the Qing dynasty and brought the province into the rule of the Republic of China.

The anarchist Constitution Protection Region of Southern Fujian was established by Chen Jiongming from 1918 to 1920.

Fujian briefly established the independent Fujian People's Government in 1933. It was re-controlled by the Republic of China in 1934.

Fujian came under a Japanese sea blockade during World War II.

People's Republic of China

[edit]After the Chinese Civil War, the People's Republic of China unified the country and took over most of Fujian, excluding the Quemoy and Matsu Islands.

In its early days, Fujian's development was relatively slow in comparison to other coastal provinces due to potential conflicts with Kuomintang-controlled Taiwan. Today, the province has the highest forest coverage rate while enjoying a high growth rate in the economy. The GDP per capita in Fujian is ranked 4-6th place among provinces of China in recent years.

Development has been accompanied by a large influx of population from the overpopulated areas to Fujian's north and west, and much of the farmland and forest, as well as cultural heritage sites such as the temples of king Wuzhu, have given way to ubiquitous high-rise buildings. Fujian faces challenges to sustain development[citation needed] while at the same time preserving Fujian's natural and cultural heritage.

In 2023, the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party and the State Council of China jointly proposed making Fujian a demonstration zone in cross-strait integration between Taiwan and mainland China. Under the plan, the Chinese government would boost economic and transportation cooperation with Taiwan and make it easier for Taiwanese people to live, buy property, access social services and study in Fujian.[33]

Geography

[edit]

The province is mostly mountainous and is traditionally said to be "eight parts mountain, one part water, and one part farmland" (八山一水一分田). The northwest is higher in altitude, with the Wuyi Mountains forming the border between Fujian and Jiangxi. It is the most forested provincial-level administrative region in China, with a 62.96% forest coverage rate in 2009.[34] Fujian's highest point is Mount Huanggang in the Wuyi Mountains, with an altitude of 2,157 metres (1.340 mi).

Fujian faces East China Sea to the east, South China Sea to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the southeast. The coastline is rugged and has many bays and islands. Major islands include Quemoy (also known as Kinmen, controlled by the Republic of China), Haitan Island, and Nanri Island. Meizhou Island occupies a central place in the cult of the goddess Matsu, the patron deity of Chinese sailors.

The Min River and its tributaries cut through much of northern and central Fujian. Other rivers include the Jin and the Jiulong. Due to its uneven topography, Fujian has many cliffs and rapids.

Fujian is separated from Taiwan by the 180 kilometres (110 mi)-wide Taiwan Strait. Some of the small islands in the Taiwan Strait are also part of the province. The islands of Kinmen and Matsu are under the administration of the Republic of China.

Fujian contains several faults, the result of a collision between the Asiatic Plate and the Philippine Sea Plate. The Changle-Naoao and Longan-Jinjiang fault zones in this area have annual displacement rates of 3–5 mm. They could cause major earthquakes in the future.[35]

Fujian has a subtropical climate, with mild winters. In January, the coastal regions average around 7–10 °C (45–50 °F) while the hills average 6–8 °C (43–46 °F). In the summer, temperatures are high, and the province is threatened by typhoons coming in from the Pacific. Average annual precipitation is 1,400–2,000 millimetres (55–79 in).

Transportation

[edit]Roads

[edit]

As of 2012[update], there are 54,876 kilometres (34,098 miles) of highways in Fujian, including 3,500 kilometres (2,200 miles) of expressways. The top infrastructure projects in recent years have been the Zhangzhou-Zhaoan Expressway (US$624 million) and the Sanmingshi-Fuzhou expressway (US$1.40 billion). The 12th Five-Year Plan, covering the period from 2011 to 2015, aims to double the length of the province's expressways to 5,500 kilometres (3,400 mi).[36]

Railways

[edit]

Due to Fujian's mountainous terrain and traditional reliance on maritime transportation, railways came to the province comparatively late. The first rail links to neighboring Jiangxi, Guangdong, and Zhejiang Province, opened respectively, in 1959, 2000, and 2009. As of October 2013, Fujian has four rail links with Jiangxi to the northwest: the Yingtan–Xiamen Railway (opened 1957), the Hengfeng–Nanping Railway (1998), Ganzhou–Longyan Railway (2005) and the high-speed Xiangtang–Putian Railway (2013). Fujian's rail link to Guangdong to the west, the Zhangping–Longchuan Railway (2000), was joined with the high-speed Xiamen–Shenzhen Railway (Xiashen Line) in late 2013. The Xiashen Line forms the southernmost section of China's Southeast Coast High-Speed Rail Corridor. The Wenzhou–Fuzhou and Fuzhou–Xiamen sections of this corridor entered operation in 2009 and link Fujian with Zhejiang with trains running at speeds of up to 250 km/h (155 mph).

Within Fujian, coastal and interior cities are linked by the Nanping–Fuzhou (1959), Zhangping–Quanzhou–Xiaocuo (2007) and Longyan–Xiamen Railways, (2012). To attract Taiwanese investment, the province intends to increase its rail length by 50 percent to 2,500 km (1,553 mi).[37]

Air

[edit]The major airports are Fuzhou Changle International Airport, Xiamen Gaoqi International Airport, Quanzhou Jinjiang International Airport, Nanping Wuyishan Airport, Longyan Guanzhishan Airport and Sanming Shaxian Airport. Xiamen is capable of handling 15.75 million passengers as of 2011. Fuzhou is capable of handling 6.5 million passengers annually with a cargo capacity of more than 200,000 tons. The airport offers direct links to 45 destinations including international routes to Japan, Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, and Hong Kong.[37]

Administrative divisions

[edit]The People's Republic of China controls most of the province and divides it into nine prefecture-level divisions: all prefecture-level cities (including a sub-provincial city):

| Administrative divisions of Fujian | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

☐ Kinmen County and Lienchiang County (Quemoy and Matsu) are administered by

Quanzhou (Kinmen Co.); Lianjiang Co., Fuzhou (most of Matsu Is.); Changle Dist. (Juguang: Dongju Is. & Xiju Is.); Meizhou, Xiuyu Dist., Putian (Wuqiu Is.); Longhai, Zhangzhou (Dongding I.). | ||||||||||

| Division code[38] | Division | Area in km2[39] | Population 2020[40] | Seat | Divisions[41] | |||||

| Districts | Counties | CL cities | ||||||||

| 350000 | Fujian Province | 121,400.00 | 41,540,086 | Fuzhou city | 31 | 42 | 11 | |||

| 350100 | Fuzhou city | 12,155.46 | 8,291,268 | Gulou District | 6 | 6 | 1 | |||

| 350200 | Xiamen city | 1,699.39 | 5,163,970 | Siming District | 6 | |||||

| 350300 | Putian city | 4,119.02 | 3,210,714 | Chengxiang District | 4 | 1 | ||||

| 350400 | Sanming city | 22,928.79 | 2,486,450 | Sanyuan District | 2 | 8 | 1 | |||

| 350500 | Quanzhou city | 11,245.00 | 8,782,285 | Fengze District | 4 | 5* | 3 | |||

| 350600 | Zhangzhou city | 12,873.33 | 5,054,328 | Longwen District | 4 | 7 | ||||

| 350700 | Nanping city | 26,280.54 | 2,645,548 | Jianyang District | 2 | 5 | 3 | |||

| 350800 | Longyan city | 19,028.26 | 2,723,637 | Xinluo District | 2 | 4 | 1 | |||

| 350900 | Ningde city | 13,452.38 | 3,146,789 | Jiaocheng District | 1 | 6 | 2 | |||

|

* - including Kinmen County, ROC (Taiwan). Claimed by the PRC. (included in the total Counties' count) | ||||||||||

| Administrative divisions in Chinese and varieties of romanizations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Chinese | Pinyin | Fuzhou BUC | Hokkien POJ |

| Fujian Province | 福建省 | Fújiàn Shěng | Hók-gióng-sēng | Hok-kiàn-séng |

| Fuzhou city | 福州市 | Fúzhōu Shì | Hók-ciŭ-chê | Hok-chiu-chhī |

| Xiamen city | 厦门市 | Xiàmén Shì | Â-muòng-chê | Ē-mn̂g-chhī |

| Putian city | 莆田市 | Pútián Shì | Può-dièng-chê | Phô͘-chhân-chhī |

| Sanming city | 三明市 | Sānmíng Shì | Săng-mìng-chê | Sam-bêng-chhī |

| Quanzhou city | 泉州市 | Quánzhōu Shì | Ciòng-ciŭ-chê | Choân-chiu-chhī |

| Zhangzhou city | 漳州市 | Zhāngzhōu Shì | Ciŏng-ciŭ-chê | Chiang-chiu-chhī |

| Nanping city | 南平市 | Nánpíng Shì | Nàng-bìng-chê | Lâm-pêng-chhī |

| Longyan city | 龙岩市 | Lóngyán Shì | Lṳ̀ng-ngàng-chê | Lêng-nâ-chhī |

| Ningde city | 宁德市 | Níngdé Shì | Nìng-dáik-chê | Lêng-tek-chhī |

All of the prefecture-level cities except Nanping, Sanming, and Longyan are found along the coast.

These nine prefecture-level cities are subdivided into 84 county-level divisions (31 districts, 11 county-level cities, and 42 counties). Those are in turn divided into 1,102 township-level divisions (653 towns, 233 townships, 19 ethnic townships, and 195 subdistricts).

The People's Republic of China claims five of the six townships of Kinmen County, Republic of China (Taiwan) as a county of the prefecture-level city of Quanzhou.[42][43][44]

The PRC claims Wuqiu Township, Kinmen County, Republic of China (Taiwan) as part of Xiuyu District of the prefecture-level city of Putian.

Finally, the PRC claims Lienchiang County (Matsu Islands), Republic of China (Taiwan) as a township of its Lianjiang County, which is part of the prefecture-level city of Fuzhou.

Together, these three groups of islands make up the Republic of China's Fujian province.

Urban areas

[edit]| Population by urban areas of prefecture & county cities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Cities | 2020 Urban area[45] | 2010 Urban area[46] | 2020 City proper |

| 1 | Xiamen | 4,617,251 | 3,119,110 | 5,163,970 |

| 2 | Fuzhou[i] | 3,723,454 | 2,824,414[ii] | 8,291,268 |

| 3 | Putian | 1,539,389 | 1,107,199 | 3,210,714 |

| 4 | Quanzhou[iii] | 1,469,157 | 1,154,731 | 8,782,285 |

| 5 | Jinjiang | 1,416,151 | 1,172,827 | see Quanzhou |

| 6 | Nan'an | 936,897 | 718,516 | see Quanzhou |

| 7 | Longyan | 886,281 | 460,086[iv] | 2,723,637 |

| 8 | Zhangzhou | 845,286 | 614,700 | 5,054,328 |

| 9 | Fuqing | 744,774 | 470,824 | see Fuzhou |

| 10 | Shishi | 589,902 | 469,969 | see Quanzhou |

| 11 | Longhai | 584,371 | 422,993 | see Zhangzhou |

| 12 | Nanping | 537,472 | 301,370[v] | 2,680,645 |

| 13 | Ningde | 425,499 | 252,497 | 3,146,789 |

| 14 | Fu'an | 397,068 | 326,019 | see Ningde |

| 15 | Sanming | 378,423 | 328,766 | 2,486,450 |

| 16 | Fuding | 351,341 | 266,779 | see Ningde |

| 17 | Yong'an | 248,425 | 213,732 | see Sanming |

| 18 | Jian'ou | 226,100 | 192,557 | see Nanping |

| 19 | Shaowu | 217,836 | 183,457 | see Nanping |

| 20 | Wuyishan | 159,308 | 122,801 | see Nanping |

| 21 | Zhangping | 147462 | 113,739 | see Longyan |

| — | Changle | see Fuzhou | 278,007[ii] | see Fuzhou |

| — | Jianyang | see Nanping | 150,756[v] | see Nanping |

- ^ Does not include Beigan Township, Dongyin Township, Juguang Township, & Nangan Township (controlled by ROC) in the city proper count.

- ^ a b New district established after 2010 census: Changle (Changle CLC). The new district not included in the urban area count of the pre-expanded city.

- ^ Does not include Kinmen County (controlled by ROC) in the city proper count.

- ^ New district established after 2010 census: Yongding (Yongding County). The new district not included in the urban area count of the pre-expanded city.

- ^ a b New district established after 2010 census: Jianyang (Jianyang CLC). The new district not included in the urban area count of the pre-expanded city.

Most populous cities in Fujian

Source: China Urban Construction Statistical Yearbook 2018 Urban Population and Urban Temporary Population[47] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Pop. | Rank | Pop. | ||||||

| 1 | Xiamen | 3,499,800 | 11 | Nan'an | 318,000 | ||||

| 2 | Fuzhou | 3,007,100 | 12 | Ningde | 282,200 | ||||

| 3 | Quanzhou | 1,365,000 | 13 | Sanming | 241,200 | ||||

| 4 | Putian | 771,000 | 14 | Longhai | 219,400 | ||||

| 5 | Zhangzhou | 528,800 | 15 | Fuding | 178,000 | ||||

| 6 | Longyan | 456,300 | 16 | Yong'an | 175,100 | ||||

| 7 | Fuqing | 361,100 | 17 | Fu'an | 169,200 | ||||

| 8 | Nanping | 356,600 | 18 | Jian'ou | 142,100 | ||||

| 9 | Shishi | 355,800 | 19 | Zhangping | 129,300 | ||||

| 10 | Jinjiang | 335,000 | 20 | Shaowu | 122,800 | ||||

Politics

[edit]List of provincial-level leaders

[edit]CCP Party Secretaries

[edit]- Zhang Dingcheng (张鼎丞): 1949–1954

- Ye Fei (叶飞): 1954–1958

- Jiang Yizhen (江一真): 1958–1970

- Han Xianchu (韩先楚): 1971–1973

- Liao Zhigao (廖志高): 1974–1982

- Xiang Nan (项南): 1982–1986

- Chen Guangyi (陈光毅): 1986–1993

- Jia Qinglin (贾庆林): 1993–1996

- Chen Mingyi (陈明义): 1996–2000

- Song Defu (宋德福): 2000–2004

- Lu Zhangong (卢展工): 2004–2009

- Sun Chunlan (孙春兰): 2009–2012

- You Quan (尤权): 2012–2017

- Yu Weiguo (于伟国): 2017–2020

- Yin Li (尹力): 2020–2022

- Zhou Zuyi (周祖翼): 2022–present

Chairpersons of Fujian People's Congress

[edit]- Liao Zhigao (廖志高): 1979–1982

- Hu Hong (胡宏): 1982–1985

- Cheng Xu (程序): 1985–1993

- Chen Guangyi (陈光毅): 1993–1994

- Jia Qinglin (贾庆林): 1994–1998

- Yuan Qitong (袁启彤): 1998–2002

- Song Defu (宋德福): 2002–2005

- Lu Zhangong (卢展工): 2005–2010

- Sun Chunlan (孙春兰): 2010–2013

- You Quan (尤权): 2013–2018

- Yu Weiguo (于伟国): 2018–2021

- Yin Li (尹力): 2021–2023

- Zhou Zuyi (周祖翼): 2023–present

Governors

[edit]- Zhang Dingcheng (张鼎丞): 1949–1954

- Ye Fei (叶飞): 1954–1959

- Jiang Yizhen (江一真): 1959

- Wu Hongxiang (伍洪祥): acting: 1960–1962

- Jiang Yizhen (江一真): 1962

- Wei Jinshui (魏金水): 1962–1967

- Han Xianchu (韩先楚): 1967–1973

- Liao Zhigao (廖志高): 1974–1979

- Ma Xingyuan (马兴元): 1979–1983

- Hu Ping (胡平): 1983–1987

- Wang Zhaoguo (王兆国): 1987–1990

- Jia Qinglin (贾庆林): 1990–1994

- Chen Mingyi (陈明义): 1994–1996

- He Guoqiang (贺国强): 1996–1999

- Xi Jinping (习近平): 1999–2002

- Lu Zhangong (卢展工): 2002–2004

- Huang Xiaojing (黄小晶): 2004–2011

- Su Shulin (苏树林): 2011–2015

- Yu Weiguo (于伟国): 2015–2018

- Tang Dengjie (唐登杰): 2018–2020

- Wang Ning (王宁): 2020–2021

- Zhao Long (赵龙): 2021–present

Economy

[edit]

Fujian is one of the more affluent provinces in China, with many industries spanning tea production, clothing, and sports manufacturers such as Anta, 361 Degrees, Xtep, Peak Sport Products and Septwolves. Fujian was one of the first provinces in China authorized by the central government to receive foreign investments.[48]: 148 Many foreign firms have operations in Fujian. They include Boeing, Dell, GE, Kodak, Nokia, Siemens, Swire, TDK, and Panasonic.[49] Within Fujian, the city of Xiamen was one of China's first special economic zones ("SEZs").[48]: 158

In 2022, Fujian's GDP was CN¥5.31 trillion (US$790 billion in nominal), ranking 8th in GDP nationwide and appearing in the world's top 20 largest sub-national economies.[6] Along with its coastal neighbours Zhejiang and Guangdong, Fujian's GDP per capita is above the national average, at CN¥126,829 (US$18,856 in nominal), the second highest GDP per capita of all Chinese provinces after Jiangsu.[6] The primary, secondary and tertiary economy respectively contributed to ¥307 billion ($45.7 billion), ¥2.51 trillion ($372.8 billion), and ¥2.50 trillion ($371 billion) to Fujian's economy.[6]

| Historical GDP of Fujian Province for 1952 –present (SNA2008)[50] (purchasing power parity of Chinese Yuan, as Int'l.dollar based on IMF WEO October 2017[51]) | |||||||||

| year | GDP | GDP per capita (GDPpc) based on mid-year population |

Reference index | ||||||

| GDP in millions | real growth (%) |

GDPpc | exchange rate 1 foreign currency to CNY | ||||||

| CNY | USD | PPP (Int'l$.) |

CNY | USD | PPP (Int'l$.) |

USD 1 | Int'l$. 1 (PPP) | ||

| 2016 | 2,881,060 | 433,744 | 822,948 | 8.4 | 74,707 | 11,247 | 21,339 | 6.6423 | 3.5009 |

| 2015 | 2,623,920 | 421,283 | 739,237 | 9.0 | 68,645 | 11,021 | 19,339 | 6.2284 | 3.5495 |

| 2014 | 2,429,260 | 395,465 | 684,221 | 9.9 | 64,097 | 10,434 | 18,053 | 6.1428 | 3.5504 |

| 2013 | 2,207,780 | 356,485 | 617,233 | 11.0 | 58,702 | 9,478 | 16,411 | 6.1932 | 3.5769 |

| 2012 | 1,988,380 | 314,991 | 559,981 | 11.4 | 53,250 | 8,436 | 14,997 | 6.3125 | 3.5508 |

| 2011 | 1,770,380 | 274,104 | 505,029 | 12.3 | 47,764 | 7,395 | 13,625 | 6.4588 | 3.5055 |

| 2010 | 1,484,580 | 219,304 | 448,432 | 13.9 | 40,320 | 5,956 | 12,179 | 6.7695 | 3.3106 |

| 2009 | 1,232,420 | 180,416 | 390,315 | 12.3 | 33,677 | 4,930 | 10,666 | 6.8310 | 3.1575 |

| 2008 | 1,088,940 | 156,793 | 342,779 | 13.0 | 29,938 | 4,311 | 9,424 | 6.9451 | 3.1768 |

| 2007 | 930,190 | 122,329 | 308,531 | 15.2 | 25,730 | 3,384 | 8,534 | 7.6040 | 3.0149 |

| 2006 | 762,740 | 95,680 | 265,052 | 14.8 | 21,226 | 2,663 | 7,376 | 7.9718 | 2.8777 |

| 2005 | 658,860 | 80,430 | 230,451 | 11.6 | 18,448 | 2,252 | 6,453 | 8.1917 | 2.8590 |

| 2000 | 376,454 | 45,474 | 138,438 | 9.3 | 11,194 | 1,352 | 4,117 | 8.2784 | 2.7193 |

| 1990 | 52,228 | 10,919 | 30,675 | 7.5 | 1,763 | 369 | 1,035 | 4.7832 | 1.7026 |

| 1980 | 8,706 | 5,810 | 5,821 | 18.4 | 348 | 232 | 233 | 1.4984 | 1.4955 |

| 1978 | 6,637 | 4,268 | 17.8 | 273 | 176 | 1.5550 | |||

| 1970 | 3,470 | 1,410 | 9.9 | 173 | 70 | 2.4618 | |||

| 1962 | 2,212 | 899 | 98.6 | 137 | 56 | 2.4618 | |||

| 1957 | 2,203 | 846 | 6.7 | 154 | 59 | 2.6040 | |||

| 1952 | 1,273 | 573 | 23.3 | 102 | 46 | 2.2227 | |||

In terms of agricultural land, Fujian is hilly and farmland is sparse. Rice is the main crop, supplemented by sweet potatoes and wheat and barley.[52] Cash crops include sugar cane and rapeseed. Fujian leads the provinces of China in longan production, and is also a major producer of lychees and tea. Seafood is another important product, with shellfish production especially prominent.

Because of its geographic location with Taiwan, Fujian has been considered the battlefield frontline in a potential war between mainland China and Taiwan. Hence, it received much less investment from the Chinese central government and developed much slower than the rest of China before 1978. Since 1978, when China opened to the world, Fujian has received significant investment from overseas Fujianese around the world, Taiwanese and foreign investment.

Minnan Golden Triangle, which includes Xiamen, Quanzhou, and Zhangzhou, accounts for 40 percent of the GDP of Fujian province.

Fujian province will be the major economic beneficiary of the opening up of direct transport with Taiwan, which commenced on December 15, 2008. This includes direct flights from Taiwan to major Fujian cities such as Xiamen and Fuzhou. In addition, ports in Xiamen, Quanzhou, and Fuzhou will upgrade their port infrastructure for increased economic trade with Taiwan.[53][54]

Fujian is the host of China International Fair for Investment and Trade annually. It is held in Xiamen to promote foreign investment for all of China.

Economic and Technological Development Zones

[edit]

- Dongshan Economic and Technology Development Zone

- Fuzhou Economic & Technical Development Zone

- Fuzhou Free Trade Zone

- Fuzhou Hi-Tech Park

- Fuzhou Taiwan Merchant Investment Area

- Jimei Taiwan Merchant Investment Area

- Meizhou Island National Tourist Holiday Resort

- Wuyi Mountain National Tourist Holiday Resort

- Xiamen Export Processing Zone

- Xiamen Free Trade Zone

- Xiamen Haicang Economic and Technological Development Zone

- Xiamen Torch New & Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone (Chinese version)

- Xinglin Taiwan Merchant Investment Area

Demographics

[edit]

As of 1832, the province was described as having an estimated "population of fourteen millions."[56] In 2021, Fujian's population was estimated to be 41.87 million, with an urbanization rate of 69.7%.[6]

Fujianese who are legally classified as Han Chinese make up 98% of the population. Various Min Chinese speakers make up the largest subgroups classified as Han Chinese in Fujian, such as Hoklo people, Fuzhounese people, Putian people and Fuzhou Tanka.

The Hakka, a Han Chinese people with their own distinct identity, live in the central and southwestern parts of Fujian. The She, an ethnic group scattered over mountainous regions in the north, is the largest minority ethnic group of the province.[57]

Many ethnic Chinese around the world (especially in Southeast Asia) trace their ancestries to the Fujianese branches of the Hoklo and Teochew peoples. Descendants of Southern Min-speaking emigrants make up the majorities of ethnic-Chinese populations in Taiwan, Singapore, Australia, Brunei, Thailand, Indonesia, and Philippines. Eastern Min-speaking people (especially Fuzhounese people) are one of the major sources of Chinese immigrants to the United States since the 1990s.[58]

Religion

[edit]- Chinese ancestral religion (31.3%)

- Christianity (3.50%)

- Other religions or not religious people[note 3] (65.2%)

The predominant religions in Fujian are Chinese folk religions, Taoist traditions, and Chinese Buddhism. According to surveys conducted in 2007 and 2009, just over 30% of the population believes and is involved in Chinese ancestral religion; 3.5% of the population identifies as Christian.[59] The reports did not give figures for other religions; 65.19% of the population may be irreligious or involved in Chinese folk religion, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, Chinese salvationist religions, or Islam. Notably, Fujian is one of the only places in the world where Manichaeism may still be practiced.[60]

In 2010, there were reportedly just under 116,000 Muslims in Fujian.[61]

|

Culture

[edit]

Because of its mountainous nature and waves of migration from central China and assimilation of numerous foreign ethnic groups such as maritime traders in the course of history, Fujian is one of the most culturally and linguistically diverse places in China. Local dialects can become unintelligible within 10 kilometres (6.2 mi), and the regional cultures and ethnic composition can be completely different from each other as well. This is reflected in the expression that "if you drive five miles in Fujian the culture changes, and if you drive ten miles, the language does".[62] Most varieties spoken in Fujian are assigned to a broad Min category. Recent classifications subdivide Min into[63][64]

- Eastern Min (the former Northern group), including the Fuzhou dialect

- Northern Min, spoken in inland northern areas

- Pu-Xian, spoken in central coastal areas

- Central Min, spoken in the west of the province

- Shao-Jiang, spoken in the northwest

- Southern Min, including the Amoy dialect and Taiwanese

The seventh subdivision of Min, Qiong Wen, is not spoken in Fujian. Hakka, another subdivision of spoken Chinese, is spoken around Longyan by the Hakka people who live there.

As is true of other provinces, the official language in Fujian is Mandarin, which is used for communication between people of different localities,[62] although native Fujian peoples still converse in their native languages and dialects respectively.

Several regions of Fujian have their own form of Chinese opera. Min opera is popular around Fuzhou; Gaojiaxi around Jinjiang and Quanzhou; Xiangju around Zhangzhou; Fujian Nanqu throughout the south, and Puxianxi around Putian and Xianyou County.

Fujian cuisine, with an emphasis on seafood, is one of the eight great traditions of Chinese cuisine. It is composed of traditions from various regions, including Fuzhou cuisine and Min Nan cuisine. The most prestigious dish is Fotiaoqiang (literally "Buddha jumps over the wall"), a complex dish making use of many ingredients, including shark fin, sea cucumber, abalone and Shaoxing wine (a type of Chinese alcoholic beverage).

Many well-known teas originate from Fujian, including oolong, Wuyi Yancha, Lapsang souchong and Fuzhou jasmine tea. Indeed, the tea processing techniques for three major classes of tea, namely, oolong, white tea, and black tea were all developed in the province. Fujian tea ceremony is an elaborate way of preparing and serving tea. The English word "tea" is borrowed from Hokkien. Mandarin and Cantonese pronounce the word chá.

Nanyin is a popular form of music of Fujian.

Fuzhou bodiless lacquer ware, a noted type of lacquer ware, is noted for using a body of clay and/or plaster to form its shape; the body later removed. Fuzhou is also known for Shoushan stone carvings.

Tourism

[edit]

Fujian is home to several tourist attractions, including four UNESCO World Heritage Sites, one of the highest in China.

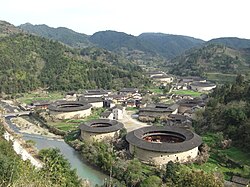

Cultural features

[edit]The Fujian Tulou are Chinese rural dwellings unique to the Hakka in southwest Fujian. These 46 buildings[65] were listed by the UNESCO as one of the World Heritage Sites in 2008.

Gulangyu Island, Xiamen, is notable for its beaches, winding lanes, and rich architecture. The island is on China's list of National Scenic Spots and is classified as a 5A tourist attraction by the China National Tourism Administration (CNTA). It was listed by the UNESCO as one of the World Heritage Site in 2017. Also in Xiamen is the South Putuo Temple.

The Guanghua Temple is a Buddhist temple in Putian. It was built in the penultimate year of the Southern Chen dynasty. Located in the northern half of the mouth of Meizhou Bay, it is about 1.8 nautical miles from the mainland and faces the Strait of Taiwan to the southeast. Covering an area of six square miles, the island is swathed in luxuriant green foliage. The coastline is indented with over 12 miles of the beach area. Another Buddhist temple, Nanshan Temple is located in Zhangzhou.

The Kaiyuan Temple is a Buddhist temple in West Street, Quanzhou, the largest in Fujian province, with an area of 78,000 square metres (840,000 square feet).[66] Although it is known as both a Hindu and Buddhist temple, on account of added Tamil-Hindu influences, the main statue in the most important hall is that of Vairocana Buddha, the main Buddha according to Huayan Buddhism.

In the capital of Fuzhou is the Yongquan Temple, a Buddhist temple built during the Tang dynasty.

The Chongwu Army Temple honors twenty-seven fallen soldiers of the People's Liberation Army who died during an attack by Nationalist forces in 1949, including five who died shielding a teenage girl during the attack.[67] The site is frequented by locals and tourists.[68]

Around Meizhou Islands is the Matsu pilgrimage.

Natural features

[edit]Mount Taimu is a mountain and a scenic resort in Fuding. It offers a grand view of mountains and sea and is famous for its natural scenery including granite caves, odd-shaped stones, cliffs, clear streams, cascading waterfalls, and cultural attractions such as ancient temples and cliff Inscriptions.

The Danxia landform in Taining was listed by the UNESCO as one of the World Heritage Sites in 2010. It is a unique type of petrographic geomorphology found in China. Danxia landform is formed from red-coloured sandstones and conglomerates of largely Cretaceous age. The landforms look very much like karst topography that forms in areas underlain by limestones, but since the rocks that form danxia are sandstones and conglomerates, they have been called "pseudo-karst" landforms. They were formed by endogenous forces (including uplift) and exogenous forces (including weathering and erosion).

The Wuyi Mountains was the first location in Fujian to be listed by UNESCO as one of the World Heritage Sites in 1999. They are a mountain range in the prefecture of Nanping and contain the highest peak in Fujian, Mount Huanggang. It is famous as a natural landscape garden and a summer resort in China.[69]

Notable individuals

[edit]The province and its diaspora abroad also have a tradition of educational achievement and have produced many important scholars, statesmen, and other notable people. These include people whose ancestral home (祖籍) is Fujian (their ancestors originated from Fujian). In addition to the below list, many notable individuals of Han Chinese descent in Taiwan, Southeast Asia, and elsewhere have ancestry that can be traced to Fujian.

Some notable individuals include (in rough chronological order):

- Han, Tang, and Song dynasties

- Baizhang Huaihai (720–814), an influential master of Chan Buddhism during the Tang dynasty

- Huangbo Xiyun (died 850), an influential master of Chan Buddhism during the Tang dynasty

- Chen Yan (849–892), Tang dynasty governor of Fujian

- Zhu Wenjin (died 945), King of Min

- Zhuo Yanming (died 945), a Buddhist monk and emperor

- Liu Congxiao (906–962), Prince of Jinjiang and Jiedushi of Qingyuan Circuit

- Chen Hongjin (914–985), Jiedushi of Pinghai Circuit

- Liu Yong (987–1053), a famous poet

- Cai Jing (1047–1126), government official and calligrapher who lived during the Northern Song dynasty

- Li Gang (1083–1140), Song dynasty politician and military leader (ancestral home is Shaowu)

- Zhu Xi (1130–1200), Confucian philosopher

- Zhen Dexiu (1178–1235), Song dynasty politician and philosopher

- Yan Yu (1191–1241), a poetry theorist and poet of the Southern Song dynasty

- Chen Wenlong (1232–1277), a scholar-general in the last years of the Southern Song dynasty

- Pu Shougeng (1250–1281), a Muslim merchant and administrator in the last years of the Southern Song dynasty

- Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties

- Chen Youding (1330–1368), Yuan dynasty military leader

- Gao Bing (1350–1423), an author and poetry theorist during Ming dynasty

- Huang Senping (14th–15th century), royal son-in-law of Sultan Muhammad Shah of Brunei

- Zhang Jing (1492–1555), Ming dynasty politician and general

- Yu Dayou (1503–1579), Ming dynasty general and martial artist

- Li Zhi (1527–1602), a philosopher, historian and writer

- Chen Di (1541–1617), Ming dynasty philologist, strategist, and traveler

- Huang Daozhou (1585–1646), Ming dynasty politician, calligrapher, and scholar

- Ingen (1592–1673), well-known Buddhist monk, poet, and calligrapher who lived during Ming dynasty

- Hong Chengchou (1593–1665), a Ming dynasty and Qing dynasty official

- Zheng Zhilong (1604–1661), an admiral, pirate leader and politician of the late Ming dynasty

- Shi Lang (1621–1696), Qing dynasty admiral

- Li Guangdi (1642–1718), Grand Secretaries of the Qing dynasty

- Koxinga (1624–1662), Ming dynasty general who expelled the Dutch from Taiwan

- Zheng Jing(1642–1681), Prince of Yanping

- Huang Shen (1687–1772), a painter during the Qing dynasty

- Lin Zexu (1785–1850), Qing dynasty scholar and official

- Chen Baochen (1848–1935), imperial preceptor of Qing dynasty

- Zhan Shi Chai (1840s–1893), entertainer as "Chang the Chinese giant"

- Huang Naishang (1849–1924), scholar, and revolutionary, discovered the town of Sibu in Sarawak, east Malaysia in 1901

- Lin Shu (1852–1924), translator, who introduced the western classics into Chinese.

- Yan Fu (1854–1921), scholar and translator

- Sa Zhenbing (1859–1952), high-ranking naval officer of Mongolian origin

- Zheng Xiaoxu (1860–1938), Prime Minister of Manchukuo

- Qiu Jin (1875–1907), revolutionary and writer

- Lin Changmin (林長民 [zh]) (1876–1925), a high-rank governor in the Beiyang Government

- Liang Hongzhi (1882–1946), President of the Executive Yuan of the Reformed Government of the Republic of China

- Yin Ju-keng (1885–1947), Chairman of the East Hebei Autonomous Government

- Lin Juemin (1887–1911), one of 72 Revolutionary Martyrs at Huanghuagang, Guangzhou

- Chen Shaokuan (1889–1969), Fleet Admiral who served as the senior commander of naval forces of the National Revolutionary Army

- Huang Jun (1890–1937), writer

- Hsien Wu (1893–1959), protein scientist

- Lin Yutang (1894–1976), writer

- Zou Taofen (1895–1944), journalist, media entrepreneur, and political activist

- Zheng Zhenduo (1898–1958), literary historian

- Lu Yin (1899–1934), writer

- 20th-21st century

- Bing Xin (1900–1999), writer

- Shu Chun Teng (1902–1970), scientist, researcher, and lecturer

- Zhang Yuzhe (1902–1986), astronomer and director of the Purple Mountain Observatory

- Hu Yepin (1903–1931), writer

- Chen Boda (1904–1989), a communist journalist, professor and political theorist

- Lin Huiyin (1904–1955), architect and writer

- Go Seigen (1914–2014), pseudonym of Go champion Wú Qīngyuán

- Lin Jiaqiao (1916-2013), a well-known mathematician

- Wang Shizhen (1916-2016), nuclear medicine physician

- Liem Sioe Liong (1916–2012), a Chinese-born Indonesian businessman of Fuqing origin, founder of Salim Group

- Zheng Min (1920–2022), a scholar and poet

- Ray Wu (1928–2008), geneticist

- Chih-Tang Sah (born 1932), well-known electronics engineer of Mongolian origin

- Chen Jingrun (1933–1996), a widely known mathematician who invented the Chen's theorem and Chen prime

- Wang Wen-hsing (born 1939), writer

- Liu Yingming (1940–2016), a mathematician and academician

- Sun Shensu (born 1943), a geochemist and Ph.D. holder from the Columbian University (ancestral home is Fuzhou)

- Chen Kaige (born 1952), film director (ancestral home is Fuzhou)

- Chen Zhangliang (born 1961), a Chinese biologist, elected as vice-governor of Guangxi in 2007

- Liu Yudong (born 1970), a professional basketball player

- Shi Zhiyong (born 1980), professional weightlifter

- Zhang Jingchu (born 1980), actress

- Lin Dan (born 1983), professional badminton player

- Jony J (born 1989), rapper and songwriter

- Xu Bin (born 1989), actor and singer

- Tian Houwei (born 1992), professional badminton player

- Oho Ou (born 1992), actor and singer

- Wang Zhelin (born 1994), professional basketball player

- Qian Kun (born 1996), singer and songwriter

- Zhang Yiming (born 1983), Internet entrepreneur, founder of ByteDance, TikTok's parent company, richest person in China as of October 2024.

- Wang Xing (born 1979), Internet entrepreneur, founder of Meituan-Dianping.

- Robin Zeng (born 1968), Tech entrepreneur, founder of Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Limited (CATL).

- Zhang Hao (born 2000), member of Korean boyband Zerobaseone.

- Tony Yang (born 1970), Chinese businessman based in Cagayan de Oro

- Alice Guo (born 1990), former mayor of Bamban, Tarlac Guō Huápíng

- Michael Yang (born 1976), Economic Adviser of President Rodrigo Duterte

Sports

[edit]Fujian includes professional sports teams in both the Chinese Basketball Association and the Chinese League One.

The representative of the province in the Chinese Basketball Association is the Fujian Sturgeons, who are based in Jinjiang, Quanzhou. The Fujian Sturgeons made their debut in the 2004–2005 season, and finished in seventh and last place in the South Division, out of the playoffs. In the 2005–2006 season, they tied for fifth, just one win away from making the playoffs.

The Xiamen Blue Lions formerly represented Fujian in the Chinese Super League, before the team's closure in 2007. Today the province is represented by Fujian Tianxin F.C., who play in the China League Two, and the Fujian Broncos.

Education and research

[edit]Fujian is considered one of China's leading provinces in education and research. As of 2023, two major cities in the province ranked in the top 45 cities in the world (Xiamen 38th and Fuzhou 45th) by scientific research output, as tracked by the Nature Index.[7]

Colleges and universities

[edit]National

[edit]- Xiamen University (founded 1921, also known as University of Amoy, "985 project", "211 project") (Xiamen)

- Huaqiao University (Quanzhou and Xiamen)

Provincial

[edit]- Fuzhou University (Fuzhou)

- Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (Fuzhou)

- Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Fuzhou)

- Fujian Medical University (Fuzhou)

- Fujian Normal University (Fuzhou)

- Fujian University of Technology (Fuzhou)

- Xiamen University (Xiamen)

- Jimei University (Xiamen)

- Xiamen University of Technology (Xiamen)

- Longyan University (Longyan)

- Minnan Normal University (Zhangzhou)

- Minjiang University (Fuzhou)

- Putian University (Putian)

- Quanzhou Normal University (Quanzhou)

- Sanming University (Sanming)

- Wuyi University (Wuyishan)

Private

[edit]- Yang-En University (Quanzhou)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ /ˌfuːdʒiˈɛn/[5] ⓘ; previously romanized as Fukien or Hokkien

- ^ a b These are the official PRC numbers as of 2022 from Fujian Provincial Statistic Bureau. Quemoy is included as a county and Matsu as a township.

- ^ If included the islands of Kinmen, Matsu and Wuqiu, claimed by the PRC but administered by the Republic of China (ROC) as part of its streamlined Fujian Province, the total area overall is 121,580 square kilometres (46,940 sq mi) in Fujian.

- ^ This may include:

- Buddhists;

- Confucians;

- Deity worshippers;

- Taoists;

- Members of folk religious sects;

- Chinese Muslims;

- And people not bound to, nor practicing any, institutional or diffuse religion.

- ^ The data was collected by the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) of 2009 and by the Chinese Spiritual Life Survey of 2007, reported and assembled by Xiuhua Wang (2015)[59] to confront the proportion of people identifying with two similar social structures: ① Christian churches, and ② the traditional Chinese religion of the lineage (i. e. people believing and worshipping ancestral deities often organised into lineage "churches" and ancestral shrines). Data for other religions with a significant presence in China (deity cults, Buddhism, Taoism, folk religious sects, Islam, et al.) was not reported by Wang.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Doing Business in China - Survey". Ministry Of Commerce - People's Republic Of China. Archived from the original on August 5, 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ "Communiqué of the Seventh National Population Census (No. 3)". National Bureau of Statistics of China. 11 May 2021. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ "zh: 2023年福建省国民经济和社会发展统计公报". fujian.gov.cn. March 14, 2024. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ "Human Development Indices (8.0)- China". Global Data Lab. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ "Fujian". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on May 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "National Data". National Bureau of Statistics of China. 1 March 2022. Archived from the original on January 9, 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Leading 200 science cities | Nature Index 2023 Science Cities | Supplements | Nature Index". www.nature.com. Retrieved 2023-11-22.

- ^ Rolett, Barry V.; Zheng, Zhuo; Yue, Yuanfu (April 2011). "Holocene sea-level change and the emergence of Neolithic seafaring in the Fuzhou Basin (Fujian, China)". Quaternary Science Reviews. 30 (7): 788–797. Bibcode:2011QSRv...30..788R. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.01.015.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Jiao, Tianlong. 2013. "The Neolithic Archaeology of Southeast China." In Underhill, Anne P., et al. A Companion to Chinese Archaeology, 599-611. Wiley-Blackwell.

- ^ a b Britannica

- ^ Fuijan. Britannica.com.

- ^ Yeung, Yue-man; Shen, Jianfa (2008). The Pan-Pearl River Delta: An Emerging Regional Economy in a Globalizing China. Chinese University Press. p. 41. ISBN 9789629963767. Archived from the original on April 18, 2022. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ Fukien. (2008). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved December 20, 2008, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/221639/Fujian Archived February 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 伊本・白图泰(著)、马金鹏(译),《伊本・白图泰游记》,宁夏人民出版社,2005年

- ^ 中国网事:千年古港福建"泉州港"被整合改名引网民争议. Xinhua News. Archived from the original on October 9, 2013. Retrieved 2014-08-17.

- ^ Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 288.

- ^ a b History of Song, vol. 483.

- ^ Xu Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 1.

- ^ Xu Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 9.

- ^ Jayne Werner; John K. Whitmore; George Dutton (21 August 2012). Sources of Vietnamese Tradition. Columbia University Press. pp. 29–. ISBN 978-0-231-51110-0. Archived from the original on August 25, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ^ Philippe Truong (2007). The Elephant and the Lotus: Vietnamese Ceramics in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. MFA Pub. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-87846-717-4. Archived from the original on January 2, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ^ Hall, Kenneth R., ed. (1 January 1955). Secondary Cities & Urban Networking in the Indian Ocean Realm, c. 1400-1800. Lexington Books. pp. 159–. ISBN 978-0-7391-3043-8. Archived from the original on September 12, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Ainslie Thomas Embree; Robin Jeanne Lewis (1988). Encyclopedia of Asian history. Scribner. p. 190. ISBN 9780684189017. Archived from the original on October 22, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ^ Alexander Woodside (1971). Vietnam and the Chinese Model: A Comparative Study of Vietnamese and Chinese Government in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 8–. ISBN 978-0-674-93721-5. Archived from the original on August 21, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ^ Geoffrey C. Gunn (1 August 2011). History Without Borders: The Making of an Asian World Region, 1000-1800. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 112–. ISBN 978-988-8083-34-3. Archived from the original on August 21, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ^ http://www.filipiknow.net/visayan-pirates-in-china/ Archived August 28, 2016, at the Wayback Machine https://archive.org/details/cu31924023289345 Archived November 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine https://archive.org/stream/cu31924023289345#page/n181/mode/2up Archived April 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine pp. 165-166. http://nightskylie.blogspot.com/2015/07/philippine-quarterly-of-culture-and.html Archived October 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Great Ming Code / Da Ming lu. University of Washington Press. September 2012. ISBN 9780295804002. Archived from the original on April 18, 2022. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ "朝鲜人笔下的十六世纪末福建面貌_江苏频道_凤凰网". Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- ^ https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/29740/1/Han_Hee_Yeon_C_201105_PhD_thesis.pdf Archived January 15, 2017, at the Wayback Machine pp. 269-271.

- ^ Chuan-chou Fu-chi (Ch.10) Year 1512

- ^ Skinner, George William; Baker, Hugh D. R. (1977). The City in late imperial China. Stanford University Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-8047-0892-0.

- ^ Seung-young Kim, "Open Door or Sphere of Influence?: The Diplomacy of the Japanese–French Entente and Fukien Question, 1905–1907." International History Review 41#1 (2019): 105-129; see also Review by Noriko Kawamura in H-DIPLO. Archived January 24, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Davidson, Helen (2023-09-13). "China unveils Taiwan economic 'integration' plan as warships conduct manoeuvres off coast". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2025-02-01.

- ^ "Forestry in Fujian Province". English.forestry.gov.cn. January 21, 2010. Archived from the original on May 3, 2012. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- ^ Guo, Jianming; Xu, Shiyang; Fan, Hailong (2017-05-05). "Neotectonic interpretations and PS-InSAR monitoring of crustal deformations in the Fujian area of China". Open Geosciences. 9 (1): 126–132. Bibcode:2017OGeo....9...10G. doi:10.1515/geo-2017-0010. ISSN 2391-5447.

- ^ "China Briefing Business Reports". Asia Briefing. 2012. Archived from the original on September 4, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2009.

- ^ a b "China Expat city Guide Dalian". China Expat. 2008. Archived from the original on February 17, 2009. Retrieved February 8, 2009.

- ^ 中华人民共和国县以上行政区划代码 (in Simplified Chinese). Ministry of Civil Affairs. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ Shenzhen Statistical Bureau. 《深圳统计年鉴2014》 (in Simplified Chinese). China Statistics Print. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved 2015-05-29.[circular reference]

- ^ Census Office of the State Council of the People's Republic of China; Population and Employment Statistics Division of the National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China (2012). 中国2010人口普查分乡、镇、街道资料 (1 ed.). Beijing: China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-6660-2.[circular reference]

- ^ Ministry of Civil Affairs (August 2014). 《中国民政统计年鉴2014》 (in Simplified Chinese). China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-7130-9.

- ^ 2018年统计用区划代码和城乡划分代码:泉州市 (in Simplified Chinese). National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China. 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

统计用区划代码 名称{...}350527000000 金门县{...}

- ^ 建治沿革 (in Simplified Chinese). Quanzhou People's Government. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

民国3年7月,金门自思明县析出置县,隶属厦门道。{...}民国22年(1933){...}12月13日,四省分别更名为闽海、延建、兴泉、龙汀。兴泉省辖莆田、仙游、晋江、南安、安溪、惠安、同安、金门、永春、德化、大田、思明十二县 ,治设晋江(今泉州市区)。{...}民国23年7月,全省设立十个行政督察区,永春、德化、惠安属第四行政督察区(专署驻仙游),晋江、南安、安溪、金门属第五行政督察区(专署驻同安)。民国24年(1935)10月,全省改为7个行政督察区、l市。惠安、晋江、南安、金门、安溪、永春、德化属第四区(专署驻同安)。民国26年4月,南安县治徙溪美。10月,日本侵略军攻陷金门岛及烈屿,金门县政府迁到大嶝乡。{...}民国27年(1938){...}8月,金门县政务由南安县兼摄。{...}民国32年(1943)9月,全省调整为8个行政督察区、2个市。第四区专署仍驻永春,下辖永春、安溪、金门、南安、晋江、惠安等九县。德化改属第六区(专署驻龙岩)。 {...}1949年8月24日,福建省人民政府(省会福州)成立。8、9月间,南安、永春、惠安、晋江、安溪相继解放。9月, 全省划为八个行政督察区。9月9日,第五行政督察专员公署成立,辖晋江、南安、同安、惠安、安溪、永春、仙游、莆田、金门(待统一)等九县。公署设晋江县城(今泉州市区)。10月9日,金门县大嶝岛、小嶝岛及角屿解放。11月24日,德化解放,归入第七行政督察区(专署驻永安县)。 1950年{...}10月17日,政务院批准德化县划归晋江区专员公署管辖;1951年1月正式接管。至此, 晋江区辖有晋江、南安、同安、安溪、永春、德化、莆田、仙游、惠安、金门(待统一)十县。{...}1955年3月12日,奉省人民委员会令,晋江区专员公署改称晋江专员公署,4月1日正式实行。同年5月,省人民政府宣布成立金门县政府。{...}1970年{...}6月18日,福建省革命委员会决定实行。于是,全区辖有泉州市及晋江、惠安、南安、同安、安溪、永春、德化、金门(待统一)八县。同年12月25日,划金门县大嶝公社归同安县管辖。{...}1992年3月6日,国务院批准,晋江撤县设市,领原晋江县行政区域,由泉州代管。1992年5月1日。晋江市人民政府成立,至此,泉州市计辖l区、2市、6县:鲤城区、石狮市、晋江市、惠安县、南安县、安溪县、永春县、德化县、金门县,(待统一)。

- ^ 泉州市历史沿革 (in Simplified Chinese). XZQH.org. 14 July 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

1949年8月至11月除金门县外各县相继解放,{...}自1949年9月起除续领原辖晋江、惠安、南安、安溪、永泰、德化、莆田、仙游、金门、同安10县外,1951年从晋江县析出城区和近郊建县级泉州市。{...}2003年末,全市总户数1715866户,总人口6626204人,其中非农业人口1696232人(均不包括金门县在内);

- ^ 国务院人口普查办公室、国家统计局人口和社会科技统计司编 (2022). 中国2020年人口普查分县资料. Beijing: China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-9772-9.

- ^ 国务院人口普查办公室、国家统计局人口和社会科技统计司编 (2012). 中国2010年人口普查分县资料. Beijing: China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-6659-6.

- ^ Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People's Republic of China(MOHURD) (2019). 中国城市建设统计年鉴2018 [China Urban Construction Statistical Yearbook 2018] (in Chinese). Beijing: China Statistic Publishing House. Archived from the original on July 18, 2020. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ a b Ang, Yuen Yuen (2016). How China Escaped the Poverty Trap. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-0020-0. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctt1zgwm1j.

- ^ Market Profiles on Chinese Cities and Provinces, http://info.hktdc.com/mktprof/china/mpfuj.htm Archived February 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ China NBS / Bulletin on Reforming Fujian's GDP Accounting and Data Release System: fj.gov.cn (23-Oct-17)[permanent dead link] (Chinese)

- ^ Purchasing power parity (PPP) for Chinese yuan is estimate according to IMF WEO (October 2017 Archived February 14, 2006, at Archive-It) data; Exchange rate of CN¥ to US$ is according to State Administration of Foreign Exchange, published on China Statistical Yearbook Archived October 20, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ ukien. (2008). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved December 20, 2008, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/221639/Fujian Archived February 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ever cuddlier". The Economist. December 18, 2008. Archived from the original on January 13, 2009. Retrieved December 20, 2008.

- ^ "China Pledges Loans to Taiwan Firms to Boost Ties (Update2)". Bloomberg. December 21, 2008. Archived from the original on July 20, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ Ruan, Jinshan (阮金山); Li, Xiuzhu (李秀珠); Lin, Kebing (林克冰); Luo, Donglian (罗冬莲); Zhou, Chen (周宸); Cai, Qinghai (蔡清海) (April 2005). 安海湾南岸滩涂养殖贝类死亡原因调查分析 [Analysis of the causes of death of farmed shellfish on the mudflats in the southern part of Anhai Bay]. 《福建水产》 [Fujian Aquaculture]. Archived from the original on December 8, 2014.

- ^ Roberts, Edmund (1837). Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 122. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- ^ "Fujian Demographics - China Maps, map of china, maps of Beijing, Shanghai, Xian, Hong Kong, Tibet". Archived from the original on February 23, 2009. Retrieved December 20, 2008.

- ^ Semple, Kirk (21 October 2009). "In Chinatown, Sound of the Future Is Mandarin". New York Times. Archived from the original on June 27, 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ a b c China General Social Survey 2009, Chinese Spiritual Life Survey (CSLS) 2007. Report by: Xiuhua Wang (2015, p. 15) Archived September 25, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dan, Jennifer Marie (2002). "Manichaeism and its Spread into China". Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ "Muslim in China, Muslim Population & Distribution & Minority in China". topchinatravel.com. Archived from the original on November 3, 2021. Retrieved 2021-08-09.

- ^ a b French, Howard W. "Uniting China to Speak Mandarin, the One Official Language: Easier Said Than Done Archived April 29, 2015, at the Wayback Machine." The New York Times. July 10, 2005. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- ^ Kurpaska, Maria (2010). Chinese Language(s): A Look Through the Prism of "The Great Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects". Walter de Gruyter. pp. 49, 52, 71. ISBN 978-3-11-021914-2.

- ^ Norman, Jerry (1988). Chinese. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.

- ^ "Fujian - My Tours Company". Retrieved 2023-10-07.

- ^ "Kaiyuan Temple". Chinaculture.org. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ Lary, Diana (2022). China's grandmothers : gender, family, and aging from late Qing to twenty-first century. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-009-06478-1. OCLC 1292532755.

- ^ Liu, Jifeng (2021-11-24). "Deifying Communist Soldiers: The Coastal Defence Culture and the Continuation of Apotheosis in Contemporary China". Asian Studies Review. 46 (4): 650–667. doi:10.1080/10357823.2021.1999904. ISSN 1035-7823. S2CID 244674139.

- ^ 陈子琰. "High-speed railway revives ancient tea road". global.chinadaily.com.cn. Archived from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved 2021-12-05.

Sources

[edit]- Economic data

External links

[edit] Fujian travel guide from Wikivoyage

Fujian travel guide from Wikivoyage- Fujian Government Website (PRC) (in Chinese)

- Fujian Provincial Government (ROC) (in Chinese)

- Complete Map of the Seven Coastal Provinces from 1821 to 1850 (in English and Chinese)

Fujian

View on GrokipediaName

Etymology and Historical Designations

The name Fujian (福建) originated in 733 AD during the Tang dynasty's Kaiyuan era, when the term was first used to designate an administrative inspectorate combining the prefectures of Fuzhou (福州) in the north and Jianzhou (建州, now Jian'ou or Nanping area) in the west, reflecting their roles as key administrative centers for governance over the region.[3] This nomenclature emphasized supervisory authority rather than etymological meanings of the characters fu (福, fortune or to support) and jian (建, to establish), which were derived directly from the place names rather than abstract administrative verbs.[3] The designation formalized the area's integration into imperial circuits, with Fujian later evolving into a circuit (lu 路) name under the Song dynasty by the 10th century.[3] Prior to this, the region bore the designation Min (闽), an abbreviation still used today, stemming from the Min River—the province's longest waterway—and ancient indigenous groups known as the Min tribes, documented as early as the Zhou dynasty (c. 1046–256 BCE) comprising seven tribal confederations inhabiting the southeastern coastal territories.[3] These tribes formed the basis for the kingdom of Minyue (闽越), a semi-autonomous state from the Warring States period (c. 475–221 BCE) through the early Han dynasty (until 110 BCE), where Min likely denoted local ethnic identities possibly linked to Austronesian-influenced groups practicing tattooing and seafaring, distinct from central Han nomenclature.[6] Under the Qin dynasty's unification in 221 BCE, the area was redesignated as Minzhong Commandery (闽中郡), marking initial Han administrative overlay on indigenous terms without fully supplanting Min.[3] Dynastic transitions preserved Fujian as the primary designation from the Song onward, with minor refinements: the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) retained it as a province-like route, while the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1912) formalized Fujian Province (sheng 省) by the late 17th century, incorporating sub-prefectures like those of Quanzhou and Zhangzhou but without substantive renaming.[3] This continuity contrasted with earlier fluid designations tied to military circuits or tribal polities, underscoring how nomenclature shifted from ethnic-geographic (Min, Minyue) to bureaucratic-imperial (Fujian) frameworks as central authority consolidated.[3]History

Prehistoric and Early Settlements

Archaeological excavations have uncovered evidence of Paleolithic human activity in Fujian dating to approximately 20,000 years ago, including a relic site near the Mulanxi River in Putian that yielded stone tools and faunal remains indicative of hunter-gatherer subsistence.[7] Further Paleolithic occupation is documented at the Longdengshan site adjacent to the Wuyi Mountains, where optically stimulated luminescence dating confirms tool-making and settlement in a subtropical forested environment around 30,000–20,000 years before present.[8] Neolithic sites proliferated along Fujian's coast from about 7,500 years ago, with the Keqiutou complex in Pingtan County representing one of the earliest, characterized by shell middens from marine foraging, pottery sherds, and pit dwellings that suggest semi-sedentary communities reliant on fishing and gathering.[9][10] The Tanshishan culture, active from roughly 5,000 to 4,300 calibrated years before present in the Fuzhou Basin, provides additional evidence of Neolithic adaptation, including cord-marked ceramics and domestic animal bones, though without indications of hierarchical social structures.[11][12] Early agriculture emerged in these coastal Neolithic contexts, with phytolith and macrofossil analyses from Keqiutou and related South China Coast sites confirming rice cultivation by at least 6,800 calibrated years before present, marking the arrival of wet-rice farming among island-oriented populations.[13] Shell middens at these locations, abundant in oyster and clam remains, reflect intensive exploitation of estuarine resources alongside incipient farming, as verified by stratigraphic and radiocarbon data from eastern Fujian coastal excavations.[14] Coastal settlements exhibit cultural affinities with proto-Austronesian groups, as the Keqiutou culture's red-slipped pottery and maritime adaptations parallel the contemporaneous Dabenkeng tradition across the Taiwan Strait, supporting models of bidirectional migration and shared seafaring technologies around 5,000–4,000 years ago.[15] These patterns indicate dispersed village-based societies with Austronesian linguistic and genetic precursors, rather than centralized polities.[16] Transitioning into the Bronze Age circa 4,000–3,000 years ago, local cultures such as Hulushan persisted with bronze artifacts and fortified villages but lacked archaeological signatures of state-level organization, including monumental architecture or widespread administrative control, consistent with tribal confederations preceding later historical kingdoms.[17]Minyue Kingdom and Early Conquests

The Kingdom of Minyue was established around 334 BCE by Wuzhu (鄣雒缯), a prince of the defeated Yue state, who fled southward and consolidated power among the indigenous Baiyue peoples in the coastal regions of present-day Fujian.[18] These Baiyue groups, distinct from the northern Huaxia (proto-Han) populations, were characterized by tribal societies with practices such as tattooing, short hairstyles, and reliance on agriculture, fishing, and metallurgy, reflecting their Austroasiatic or Tai-Kadai linguistic and cultural affiliations rather than Sino-Tibetan Han origins.[19] During the Qin dynasty's southward expansion from 221 to 214 BCE, armies under generals like Tu Sui targeted Baiyue territories, including Minyue lands, to secure resources and labor, but faced fierce guerrilla resistance in the rugged terrain, leading to incomplete control and heavy Qin casualties. Minyue maintained semi-autonomy as a peripheral kingdom, occasionally allying or clashing with neighboring states like Dong'ou. The Han dynasty initially recognized Minyue kings as vassals after 202 BCE, but tensions escalated when Minyue invaded the allied Dong'ou in 138 BCE, prompting Han interventions; a second campaign in 135 BCE addressed ongoing conflicts between the two Yue kingdoms.[20] The decisive Han conquest occurred in 110 BCE under Emperor Wu, following Minyue king Zou Yazu's execution of Han envoys and alignment with Nanyue; General Yang Pu led forces that overran the capital Ye (near Fuzhou), capturing the royal family.[20] A subsequent rebellion by Minyue elites and tribes against Han officials was crushed, resulting in the kingdom's partition into Han commanderies—Minzhong (southern Fujian), Nanye (northern Guangdong), and Dongye (coastal Zhejiang-Fujian)—with mass relocation of over 100,000 Minyue inhabitants northward to dilute resistance.[20] While Han garrisons and settlers introduced administrative structures and Confucian elites, sinicization remained partial; tribal hierarchies endured in inland highlands, local dialects and customs like drum towers and animist rituals persisted, evidenced by archaeological finds of hybrid bronze artifacts blending Yue motifs with Han styles into the Eastern Han period.[21]Imperial Dynasties: Qin to Song

The Qin dynasty incorporated the Fujian region into the empire in 222 BC by establishing Minzhong Commandery, initiating administrative control over the Minyue territories previously held by local kingdoms.[6] This colonization effort involved military campaigns against the Baiyue peoples, including forced migrations of Han Chinese settlers to bolster imperial presence and agricultural development.[22] Following the Qin's collapse, the Han dynasty reasserted control after suppressing Minyue rebellions, notably conquering the kingdom in 110 BC under Emperor Wu, which led to the division of the area into commanderies such as Dongye and Nanye.[6] During the Han period, infrastructure development included the construction of road networks to facilitate troop movements, taxation, and Han migration into the mountainous interior, promoting sinicization and economic integration with the central plains.[23] These efforts transformed Fujian from a frontier zone into a administratively structured periphery, with local elites gradually adopting Han bureaucratic norms, though resistance persisted through sporadic uprisings. By the Three Kingdoms and Jin eras, the region contributed timber, metals, and naval resources to imperial campaigns, underscoring its strategic value.[22] In the Tang dynasty (618–907), Fujian was organized as the Jiannan Circuit, with ports like Quanzhou emerging as key hubs for maritime trade, rivaling Guangzhou in volume by the late 8th century and handling exports of silk, porcelain, and tea to Southeast Asia and beyond.[24] This trade boom generated substantial fiscal revenue through customs duties, supporting Tang military expenditures, while administrative reforms emphasized coastal defense against piracy.[25] The Song dynasty (960–1279) marked Fujian's commercial zenith, with Quanzhou—known to foreigners as Zayton—becoming one of the world's largest ports, facilitating the Maritime Silk Road and amassing wealth from spices, ivory, and Arabian goods in exchange for Chinese manufactures.[26] Fiscal contributions from Fujian's trade taxes were critical to the Song's monetized economy, funding innovations in banking and currency, though high taxation rates sparked rebellions such as the Fang La uprising in 1120, which engulfed parts of Fujian and Zhejiang before suppression.[27] Despite Jurchen invasions displacing the capital southward, Fujian's ports sustained imperial revenues, integrating the province as a vital economic artery until the dynasty's end.[28]Yuan, Ming, and Qing Eras