Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Merychippus

View on Wikipedia

| Merychippus Temporal range: Miocene,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeletal reconstruction of Merychippus on display at the American Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Equidae |

| Subfamily: | Equinae |

| Genus: | †Merychippus Leidy, 1856 |

| Type species | |

| †Merychippus insignis | |

| Species | |

|

Species

| |

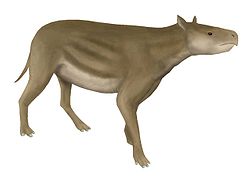

Merychippus is an extinct proto-horse of the family Equidae that was endemic to North America during the Miocene, 15.97–5.33 million years ago.[2] It had three toes on each foot and is the first horse known to have grazed.

Discovery and naming

[edit]

Merychippus was named by Joseph Leidy (1856). Numerous authors assigned the type species – Merychippus insignis – to Protohippus, but this is ignored. It was assigned to the Equidae by Leidy (1856) and Carroll (1988), and to the Equinae by MacFadden (1998) and Bravo-Cuevas and Ferrusquía-Villafranca (2006).[3][4][5] The genus name comes from Ancient Greek μηρυκασθαι (mērukasthai), meaning "to ruminate", and ἵππος (híppos), meaning "horse", but current evidence does not support Merychippus ruminating.

Description

[edit]

Merychippus lived in groups. It was about 100 cm (39 in) tall[6] and at the time it was the tallest equine to have existed. Its muzzle was longer, deeper jaw, and eyes wider apart than any other horse-like animal to date. The brain was also much larger, making it smarter and more agile. Merychippus was the first equine to have the distinctive head shape of today's horses.

The Miocene was a time of drastic change in environment, with woodlands transforming into grass plains.[7] This led to evolutionary changes in the hooves and teeth of equids. A change in surface from soft, uneven mud to hard grasslands meant there was less need for increased surface area.[7] The foot was fully supported by ligaments, and the middle toe developed into a hoof that did not have a pad on the bottom. In some Merychippus species, the side toes were larger, whereas in others, they had become smaller and only touched the ground when running. The transformation into plains also meant Merychippus began consuming more phytolith rich plants. This led to the presence of hypsodont teeth. Such teeth range from medium to intense crown height, are curved, covered in large amounts of cement, and are characteristic of grazing animals[8]

Equid size also increased, with Merychippus ranging, on average, between 71 and 100.6 kg.[9]

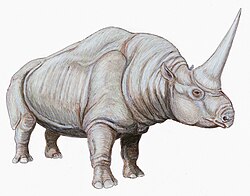

Classification

[edit]By the end of the Miocene era, Merychippus was one of the first quick grazers. It gave rise to at least 19 different species of grazers, which can be categorized into three major groups. This burst of diversification, termed an adaptive radiation, is often known as the "Merychippine radiation".[citation needed]

The first was a series of three-toed grazers known as hipparions. These were very successful and split into four genera and at least 16 species, including small and large grazers and browsers with large and elaborate facial fossae. The second was a group of smaller horses, known as protohippines, which included Protohippus and Calippus. The last was a line of "true equines" in which the side toes were smaller than those of other proto-horses. In later genera, these were lost altogether as a result of the development of side ligaments that helped stabilize the middle toe during running.

References

[edit]

- ^ "Fossilworks: Merychippus insignis". Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Fossilworks: Merychippus". Archived from the original on 13 May 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ R. L. Carroll. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York 1–698

- ^ B. J. MacFadden. 1998. Equidae. In C. M. Janis, K. M. Scott, and L. L. Jacobs (eds.), Evolution of Tertiary Mammals of North America 1:537–559

- ^ V. M. Bravo-Cuevas and I. Ferrusquía-Villafranca. 2006. Merychippus (Mammalia, Perissodactyla, Equidae) from the Middle Miocene of state of Oaxaca, southeastern Mexico. Géobios 39:771–784

- ^ Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. pp. 256–257. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- ^ a b MacFadden, B. J.. 1992. Fossil Horses: Systematics, Paleobiology, and Evolution of the Family Equidae. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- ^ Matthew, W. D.. 1926. The Evolution of the Horse: A Record and Its Interpretation. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 1:139–185.

- ^ MacFadden, B. J. 1986. Fossil horses from "Eohippus" (Hyracotherium) to Equus: scaling, Cope's Law, and the evolution of body size. Paleobiology, 12:355–369.