Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance

View on Wikipedia| Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Benign monoclonal gammopathy, monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance, monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance,[1] unknown or uncertain may be substituted for undetermined |

| |

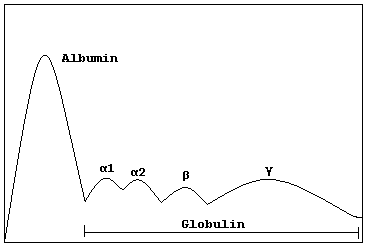

| Schematic representation of a normal protein electrophoresis gel. A small spike would be present in the gamma (γ) band in MGUS | |

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) is a plasma cell dyscrasia in which plasma cells or other types of antibody-producing cells secrete a myeloma protein, i.e. an abnormal antibody, into the blood; this abnormal protein is usually found during standard laboratory blood or urine tests. MGUS resembles multiple myeloma and similar diseases, but the levels of antibodies are lower,[2] the number of plasma cells (white blood cells that secrete antibodies) in the bone marrow is lower, and it rarely has symptoms or major problems. However, since MGUS can progress to multiple myeloma, with a rate ranging from 0.5% to 1.5% per year depending on the risk category, yearly monitoring is recommended.

The progression from MGUS to multiple myeloma usually involves several steps. In rare cases, it may also be related with a slowly progressive symmetric distal sensorimotor neuropathy.[3]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]People with monoclonal gammopathy generally do not experience signs or symptoms.[1] Some people may experience a rash or nerve problems, such as numbness or tingling.[1] MGUS is usually detected by chance when the patient has a blood test for another condition or as part of standard screening.[1]

Pathophysiology

[edit]Pathologically, the lesion in MGUS is in fact very similar to that in multiple myeloma. There is a predominance of clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow with an abnormal immunophenotype (CD38+ CD56+ CD19−) mixed in with cells of a normal phenotype (CD38+ CD56− CD19+);[4][5] in MGUS, on average more than 3% of the clonal plasma cells have the normal phenotype, whereas in multiple myeloma, less than 3% of the cells have the normal phenotype.[6]

Diagnosis

[edit]MGUS is a common, age-related medical condition characterized by an accumulation of bone marrow plasma cells derived from a single abnormal clone. Patients may be diagnosed with MGUS if they fulfill the following four criteria:[7]

- A monoclonal paraprotein band less than 30 g/L (< 3g/dL);

- Plasma cells less than 10% on bone marrow examination;

- No evidence of bone lesions, anemia, hypercalcemia, or chronic kidney disease related to the paraprotein, and

- No evidence of another B-cell proliferative disorder.

Differential diagnosis

[edit]Several other illnesses can present with a monoclonal gammopathy, and the monoclonal protein may be the first discovery before a formal diagnosis is made:

- Multiple myeloma

- Smouldering multiple myeloma

- Waldenström macroglobulinemia

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, particularly Splenic marginal zone lymphoma[8] and Lymphoplasmocytic lymphoma

- Connective tissue disease such as lupus[9]

- Immunosuppression following organ transplantation

- Guillain–Barré syndrome[10]

- Tempi syndrome[11]

- POEMS[12]

- Hepatitis C

- AIDS

Management

[edit]MGUS occurs in over 3 percent of the White population over the age of 50, and is typically detected as an incidental finding when patients undergo a protein electrophoresis as part of an evaluation for a wide variety of clinical symptoms and disorders (e.g., peripheral neuropathy, vasculitis, hemolytic anemia, skin rashes, hypercalcemia, or elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate). Although patients with MGUS have sometimes been reported to have peripheral neuropathy, a debilitating condition which causes bizarre sensory problems to painful sensory problems,[13] no treatment is indicated.[citation needed]

The protein electrophoresis test should be repeated annually, and if there is any concern for a rise in the level of monoclonal protein, then prompt referral to a hematologist is required. The hematologist, when first evaluating a case of MGUS, will usually perform a skeletal survey (X-rays of the proximal skeleton), check the blood for hypercalcemia and deterioration in renal function, check the urine for Bence Jones protein and perform a bone marrow biopsy. If none of these tests are abnormal, a patient with MGUS is followed up once every 6 months to a year with a blood test (serum protein electrophoresis).[citation needed]

Prognosis

[edit]At the Mayo Clinic, MGUS transformed into multiple myeloma or similar lymphoproliferative disorders at the rate of about 0.5–2% a year depending on risk category. However, because they were elderly, most patients with MGUS died of something else and did not go on to develop multiple myeloma. When this was taken into account, only 11.2% developed lymphoproliferative disorders.[14]

Kyle et al. studied the prevalence of myeloma in the population as a whole (not clinic patients) in Olmsted County, Minnesota. They found that the prevalence of MGUS was 3.2% in people above 50, with a slight male predominance (4.0% vs. 2.7%). Prevalence increased with age: of people over 70 up to 5.3% had MGUS, while in the over-85 age group the prevalence was 7.5%. In the majority of cases (63.5%), the paraprotein level was <1 g/dL, while only a very small group had levels over 2 g/dL.[15]

A study of monoclonal protein levels conducted in Ghana showed a prevalence of MGUS of approximately 5.9% in African men over the age of 50.[16]

In 2009, prospective data demonstrated that all or almost all cases of multiple myeloma are preceded by MGUS.[17]

In addition to multiple myeloma, MGUS may also progress to Waldenström's macroglobulinemia or primary amyloidosis.[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Kaushansky, Kenneth (2016). Williams Hematology. United States: McGraw Hill. pp. 1723–1727. ISBN 9780071833011.

- ^ Agarwal, A; Ghobrial, IM (1 March 2013). "Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smoldering multiple myeloma: a review of the current understanding of epidemiology, biology, risk stratification, and management of myeloma precursor disease". Clinical Cancer Research. 19 (5): 985–94. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2922. PMC 3593941. PMID 23224402.

- ^ Kahn S. N.; Riches P. G.; Kohn J. (1980). "Paraproteinaemia in neurological disease: incidence, associations, and classification of monoclonal immunoglobulins". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 33 (7): 617–621. doi:10.1136/jcp.33.7.617. PMC 1146171. PMID 6253529.

- ^ Zhan F, Hardin J, Kordsmeier B, Bumm K, Zheng M, Tian E, Sanderson R, Yang Y, Wilson C, Zangari M, Anaissie E, Morris C, Muwalla F, van Rhee F, Fassas A, Crowley J, Tricot G, Barlogie B, Shaughnessy J (2002). "Global gene expression profiling of multiple myeloma, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, and normal bone marrow plasma cells". Blood. 99 (5): 1745–1757. doi:10.1182/blood.V99.5.1745. PMID 11861292.

- ^ Magrangeas F, Nasser V, Avet-Loiseau H, Loriod B, Decaux O, Granjeaud S, Bertucci F, Birnbaum D, Nguyen C, Harousseau J, Bataille R, Houlgatte R, Minvielle S (2003). "Gene expression profiling of multiple myeloma reveals molecular portraits in relation to the pathogenesis of the disease". Blood. 101 (12): 4998–5006. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-11-3385. PMID 12623842.

- ^ Ocqueteau M, Orfao A, Almeida J, Bladé J, González M, García-Sanz R, López-Berges C, Moro M, Hernández J, Escribano L, Caballero D, Rozman M, San Miguel J (1998). "Immunophenotypic characterization of plasma cells from monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance patients. Implications for the differential diagnosis between MGUS and multiple myeloma". Am J Pathol. 152 (6): 1655–65. PMC 1858455. PMID 9626070.

- ^ International Myeloma Working Group (2003). "Criteria for the classification of monoclonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma and related disorders: a report of the International Myeloma Working Group". Br J Haematol. 121 (5): 749–757. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04355.x. PMID 12780789. S2CID 3195084.

- ^ Murakami H, Irisawa H, Saitoh T, Matsushima T, Tamura J, Sawamura M, Karasawa M, Hosomura Y, Kojima M (1997). "Immunological abnormalities in splenic marginal zone cell lymphoma". Am. J. Hematol. 56 (3): 173–178. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8652(199711)56:3<173::AID-AJH7>3.0.CO;2-V. PMID 9371530.

- ^ Larking-Pettigrew M, Ranich T, Kelly R (1999). "Rapid onset monoclonal gammopathy in cutaneous lupus erythematosus: interference with complement C3 and C4 measurement". Immunol. Invest. 28 (4): 269–276. doi:10.3109/08820139909060861. PMID 10454004.

- ^ Czaplinski A, Steck A (2004). "Immune mediated neuropathies--an update on therapeutic strategies". J. Neurol. 251 (2): 127–137. doi:10.1007/s00415-004-0323-5. PMID 14991345. S2CID 13218864.

- ^ Sykes, David B.; Schroyens, Wilfried; O'Connell, Casey (2011). "TEMPI Syndrome – A Novel Multisystem Disease". N Engl J Med. 365 (5): 475–477. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1106670. PMID 21812700. S2CID 35990145.

- ^ a b Go, Ronald S.; Rajkumar, S. Vincent (2018-01-11). "How I manage monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance". Blood. 131 (2): 163–173. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-09-807560. ISSN 0006-4971. PMC 5757684. PMID 29183887.

- ^ Nobile-Orazio E.; et al. (June 1992). "Peripheral neuropathy in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: prevalence and immunopathogenetic studies". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 85 (6): 383–390. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.1992.tb06033.x. PMID 1379409. S2CID 30788715.

- ^ Bladé J (2006). "Clinical practice. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance". N Engl J Med. 355 (26): 2765–2770. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp052790. PMID 17192542.

- ^ Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, Larson DR, Plevak MF, Offord JR, Dispenzieri A, Katzmann JA, Melton LJ 3rd (28 December 2006). "Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance". N Engl J Med. 354 (13): 1362–1369. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa054494. PMID 16571879.

- ^ Landgren O, Katzmann JA, Hsing AW, Pfeiffer RM, Kyle RA, Yeboah ED, Biritwum RB, Tettey Y, Adjei AA, Larson DR, Dispenzieri A, Melton LJ 3rd, Goldin LR, McMaster ML, Caporaso NE, Rajkumar SV (Dec 2007). "Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance among men in Ghana". Mayo Clin Proc. 82 (12): 1468–1473. doi:10.4065/82.12.1468. PMID 18053453.

- ^ Landgren O, Kyle RA, Pfeiffer RM, Katzmann JA, Caporaso NE, Hayes RB, Dispenzieri A, Kumar S, Clark RJ, Baris D, Hoover R, Rajkumar SV (28 May 2009). "Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) consistently precedes multiple myeloma: a prospective study". Blood. 113 (22): 5412–7. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-12-194241. PMC 2689042. PMID 19179464.

Further reading

[edit]- Agarwal, A; Ghobrial, IM (1 March 2013). "Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smoldering multiple myeloma: a review of the current understanding of epidemiology, biology, risk stratification, and management of myeloma precursor disease". Clinical Cancer Research. 19 (5): 985–94. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2922. PMC 3593941. PMID 23224402.

- Weiss, BM; Kuehl, WM (Apr 2010). "Advances in understanding monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance as a precursor of multiple myeloma". Expert Review of Hematology. 3 (2): 165–74. doi:10.1586/ehm.10.13. PMC 2869099. PMID 20473362.

- Pérez-Persona, E; Vidriales, MB; Mateo, G; García-Sanz, R; Mateos, MV; de Coca, AG; Galende, J; Martín-Nuñez, G; Alonso, JM; de Las Heras, N; Hernández, JM; Martín, A; López-Berges, C; Orfao, A; San Miguel, JF (Oct 1, 2007). "New criteria to identify risk of progression in monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance and smoldering multiple myeloma based on multiparameter flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow plasma cells". Blood. 110 (7): 2586–92. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-05-088443. hdl:10366/154361. PMID 17576818.

- Barlogie, B; van Rhee, F; Shaughnessy JD Jr; Epstein, J; Yaccoby, S; Pineda-Roman, M; Hollmig, K; Alsayed, Y; Hoering, A; Szymonifka, J; Anaissie, E; Petty, N; Kumar, NS; Srivastava, G; Jenkins, B; Crowley, J; Zeldis, JB (Oct 15, 2008). "Seven-year median time to progression with thalidomide for smoldering myeloma: partial response identifies subset requiring earlier salvage therapy for symptomatic disease". Blood. 112 (8): 3122–5. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-06-164228. PMC 2569167. PMID 18669874.

- Rossi, F; Petrucci, MT; Guffanti, A; Marcheselli, L; Rossi, D; Callea, V; Vincenzo, F; De Muro, M; Baraldi, A; Villani, O; Musto, P; Bacigalupo, A; Gaidano, G; Avvisati, G; Goldaniga, M; Depaoli, L; Baldini, L (Jul 1, 2009). "Proposal and validation of prognostic scoring systems for IgG and IgA monoclonal gammopathies of undetermined significance". Clinical Cancer Research. 15 (13): 4439–45. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3150. PMID 19509142.

- Golombick, T; Diamond, TH; Badmaev, V; Manoharan, A; Ramakrishna, R (Sep 15, 2009). "The potential role of curcumin in patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undefined significance--its effect on paraproteinemia and the urinary N-telopeptide of type I collagen bone turnover marker". Clinical Cancer Research. 15 (18): 5917–22. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2217. PMID 19737963.

- Rajkumar, SV (Sep 15, 2009). "Prevention of progression in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance". Clinical Cancer Research. 15 (18): 5606–8. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1575. PMC 2759099. PMID 19737944.

- Berenson, JR; Anderson, KC; Audell, RA; Boccia, RV; Coleman, M; Dimopoulos, MA; Drake, MT; Fonseca, R; Harousseau, JL; Joshua, D; Lonial, S; Niesvizky, R; Palumbo, A; Roodman, GD; San-Miguel, JF; Singhal, S; Weber, DM; Zangari, M; Wirtschafter, E; Yellin, O; Kyle, RA (Jul 2010). "Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a consensus statement". British Journal of Haematology. 150 (1): 28–38. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08207.x. PMID 20507313. S2CID 19093884.

- Kyle, RA; Durie, BG; Rajkumar, SV; Landgren, O; Blade, J; Merlini, G; Kröger, N; Einsele, H; Vesole, DH; Dimopoulos, M; San Miguel, J; Avet-Loiseau, H; Hajek, R; Chen, WM; Anderson, KC; Ludwig, H; Sonneveld, P; Pavlovsky, S; Palumbo, A; Richardson, PG; Barlogie, B; Greipp, P; Vescio, R; Turesson, I; Westin, J; Boccadoro, M; International Myeloma Working, Group (Jun 2010). "Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma: IMWG consensus perspectives risk factors for progression and guidelines for monitoring and management". Leukemia. 24 (6): 1121–7. doi:10.1038/leu.2010.60. PMC 7020664. PMID 20410922.