Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Plasma cell

View on Wikipedia| Plasma cell | |

|---|---|

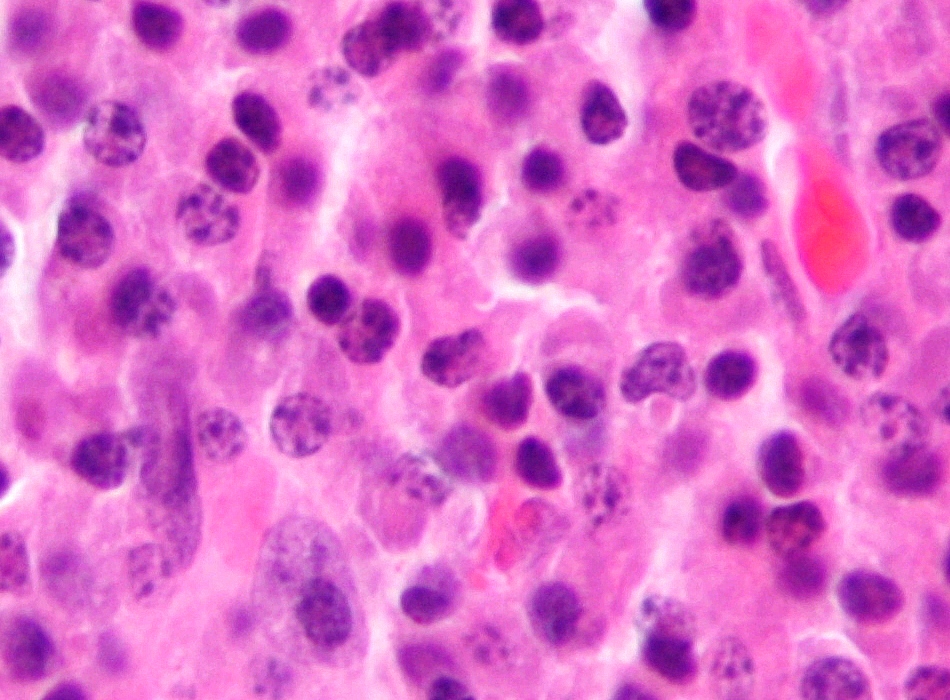

Micrograph of malignant plasma cells (plasmacytoma), many displaying characteristic "clockface nuclei", also seen in normal plasma cells. H&E stain. | |

Micrograph of a plasma cell with distinct clear perinuclear region of the cytoplasm, which contains large numbers of Golgi bodies. | |

| Details | |

| System | Lymphatic system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | plasmocytus |

| MeSH | D010950 |

| TH | H2.00.03.0.01006 |

| FMA | 70574 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

Plasma cells, also called plasma B cells or effector B cells, are white blood cells that originate in the lymphoid organs as B cells[1] and secrete large quantities of proteins called antibodies in response to being presented with specific substances called antigens. These antibodies are transported from the plasma cells by the blood plasma and the lymphatic system to the site of the target antigen (foreign substance), where they initiate its neutralization or destruction. B cells differentiate into plasma cells that produce antibody molecules closely modeled after the receptors of the precursor B cell.[2]

Structure

[edit]

Plasma cells are large lymphocytes with abundant cytoplasm and a characteristic appearance on light microscopy. They have basophilic cytoplasm and an eccentric nucleus with heterochromatin in a characteristic cartwheel or clock face arrangement. Their cytoplasm also contains a pale zone that on electron microscopy contains an extensive Golgi apparatus and centrioles. Abundant rough endoplasmic reticulum combined with a well-developed Golgi apparatus makes plasma cells well-suited for secreting immunoglobulins.[3] Other organelles in a plasma cell include ribosomes, lysosomes, mitochondria, and the plasma membrane.[citation needed]

Surface antigens

[edit]Terminally differentiated plasma cells express relatively few surface antigens, and do not express common pan-B cell markers, such as CD19 and CD20. Instead, plasma cells are identified through flow cytometry by their additional expression of CD138, CD78, and the Interleukin-6 receptor. In humans, CD27 is a good marker for plasma cells; naïve B cells are CD27−, memory B-cells are CD27+ and plasma cells are CD27++.[4]

The surface antigen CD138 (syndecan-1) is expressed at high levels.[5]

Another important surface antigen is CD319 (SLAMF7). This antigen is expressed at high levels on normal human plasma cells. It is also expressed on malignant plasma cells in multiple myeloma. Compared with CD138, which disappears rapidly ex vivo, the expression of CD319 is considerably more stable.[6]

Development

[edit]After leaving the bone marrow, the B cell acts as an antigen-presenting cell (APC) and internalizes offending antigens, which are taken up by the B cell through receptor-mediated endocytosis and processed. Pieces of the antigen (which are now known as antigenic peptides) are loaded onto MHC II molecules, and presented on its extracellular surface to CD4+ T cells (sometimes called T helper cells). These T cells bind to the MHC II-antigen molecule and cause activation of the B cell. This is a type of safeguard to the system, similar to a two-factor authentication method. First, the B cells must encounter a foreign antigen and are then required to be activated by T helper cells before they differentiate into specific cells.[7]

Upon stimulation by a T cell, which usually occurs in germinal centers of secondary lymphoid organs such as the spleen and lymph nodes, the activated B cell begins to differentiate into more specialized cells. Germinal center B cells may differentiate into memory B cells or plasma cells. Most of these B cells will become plasmablasts (or "immature plasma cells"), and eventually plasma cells, and begin producing large volumes of antibodies. Some B cells will undergo a process known as affinity maturation.[8] This process favors, by selection for the ability to bind antigen with higher affinity, the activation and growth of B cell clones able to secrete antibodies of higher affinity for the antigen.[9]

Immature plasma cells

[edit]

The most immature blood cell that is considered of plasma cell lineage is the plasmablast.[10] Plasmablasts secrete more antibodies than B cells, but less than plasma cells.[11] They divide rapidly and are still capable of internalizing antigens and presenting them to T cells.[11] A cell may stay in this state for several days, and then either die or irrevocably differentiate into a mature, fully differentiated plasma cell.[11] Differentiation of mature B cells into plasma cells is dependent upon the transcription factors Blimp-1/PRDM1, BCL6, and IRF4.[9]

Function

[edit]Unlike their precursors, plasma cells cannot switch antibody classes, cannot act as antigen-presenting cells because they no longer display MHC-II, and do not take up antigen because they no longer display significant quantities of immunoglobulin on the cell surface.[11] However, continued exposure to antigen through those low levels of immunoglobulin is important, as it partly determines the cell's lifespan.[11]

The lifespan, class of antibodies produced, and the location that the plasma cell moves to also depends on signals, such as cytokines, received from the T cell during differentiation.[12] Differentiation through a T cell-independent antigen stimulation (stimulation of a B cell that does not require the involvement of a T cell) can happen anywhere in the body[8] and results in short-lived cells that secrete IgM antibodies.[12] The T cell-dependent processes are subdivided into primary and secondary responses: a primary response (meaning that the T cell is present at the time of initial contact by the B cell with the antigen) produces short-lived cells that remain in the extramedullary regions of lymph nodes; a secondary response produces longer-lived cells that produce IgG and IgA, and frequently travel to the bone marrow.[12] For example, plasma cells will likely secrete IgG3 antibodies if they matured in the presence of the cytokine interferon-gamma. Since B cell maturation also involves somatic hypermutation (a process completed before differentiation into a plasma cell), these antibodies frequently have a very high affinity for their antigen.[citation needed]

Plasma cells can only produce a single kind of antibody in a single class of immunoglobulin. In other words, every B cell is specific to a single antigen, but each cell can produce several thousand matching antibodies per second.[13] This prolific production of antibodies is an integral part of the humoral immune response.[citation needed]

Long-lived plasma cells

[edit]The current findings suggest that after the process of affinity maturation in germinal centers, plasma cells develop into one of two types of cells: short-lived plasma cells (SLPC) or long-lived plasma cells (LLPC). LLPC mainly reside in the bone marrow for a long period of time and secrete antibodies, thus providing long-term protection. LLPC can maintain antibody production for decades or even for the lifetime of an individual,[14][15] and, unlike B cells, LLPC do not need antigen restimulation to generate antibodies. Human LLPC population can be identified as CD19– CD38hi CD138+ cells.[16]

The long-term survival of LLPC are dependent on a specific environment in the bone marrow, the plasma cell survival niche.[17] Removal of an LLPC from its survival niche results in its rapid death. A survival niche can only support limited number of LLPC, thus the niche's environment must protect its LLPC cells but be able to accept new arrivals.[18][19] The plasma cell survival niche is defined by a combination of cellular and molecular factors and though it has yet to be properly defined, molecules such as IL-5, IL-6, TNF-α, stromal cell-derived factor-1α and signalling via CD44 have been shown to play a role in the survival of LLPC.[20] LLPC can also be found, to a lesser degree, in gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), where they produce IgA antibodies and contribute to mucosal immunity. Recent findings suggest that plasma cells in the gut do not necessarily need to be generated de novo from active B cells but there are also long-lived PC, suggesting the existence of a similar survival niche.[21] Tissue specific niches that allow for the survival of LLPC have been also described in nasal-associated lymphoid tissues (NALT), human tonsillar lymphoid tissues and human mucosa or mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues (MALT).[22][23][24][25]

Originally it was thought that the continuous production of antibodies is a result of constant replenishment of short-lived plasma cells by memory B cell re-stimulation. Recent findings, however, show that some PC are truly long-lived. The absence of antigens and the depletion of B cells does not appear to have an effect on the production of high-affinity antibodies by the LLPC. Prolonged depletion of B cells (with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody treatment that affects B cells but not PC) also did not affect antibody titres.[26][27][28] LLPC secrete high levels of IgG independently of B cells. LLPC in bone marrow are the main source of circulating IgG in humans.[29] Even though IgA production is traditionally associated with mucosal sites, some plasma cells in bone marrow also produce IgA.[30] LLPC in bone marrow have been observed producing IgM.[31]

Clinical significance

[edit]Plasmacytoma, multiple myeloma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, heavy chain disease, and plasma cell leukemia are cancers of the plasma cells.[32] Multiple myeloma is frequently identified because malignant plasma cells continue producing an antibody, which can be detected as a paraprotein. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) is a plasma cell dyscrasia characterized by the secretion of a myeloma protein into the blood and may lead to multiple myeloma.[33]

Common variable immunodeficiency is thought to be due to a problem in the differentiation from lymphocytes to plasma cells. The result is a low serum antibody level and risk of infections.[citation needed]

Primary amyloidosis (AL) is caused by the deposition of excess immunoglobulin light chains which are secreted from plasma cells.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hall, John E.; Hall, Michael E. (2020). "Resistance of the Body to Infection : II. Immunity and Allergy". Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology E-Book: Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology (14th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 459–470. ISBN 978-0-323-64003-9. OCLC 1159243083.

- ^ "Plasma cell - biology". britannica.com.

- ^ "Plasma Cell - LabCE.com, Laboratory Continuing Education". www.labce.com. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ Bona C, Bonilla FA, Soohoo M (1996). "5". Textbook of Immunology (2 ed.). CRC Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-3-7186-0596-5.

- ^ Rawstron, Andy C. (2006). "Immunophenotyping of Plasma Cells". Current Protocols in Cytometry. 36: Unit6.23. doi:10.1002/0471142956.cy0623s36. PMID 18770841.

- ^ Frigyesi I, Adolfsson J, Ali M, Christophersen MK, Johnsson E, Turesson I, et al. (February 2014). "Robust isolation of malignant plasma cells in multiple myeloma". Blood. 123 (9): 1336–40. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-09-529800. PMID 24385542.

- ^ Hoffbrand, A. V. (2011). "Chapter 9 White Cells: Lymphocytes". Essential haematology. P. A. H. Moss, J. E. Pettit (6th ed.). Malden, Mass.: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-29397-3. OCLC 768731797.

- ^ a b Neuberger MS, Honjo T, Alt FW (2004). Molecular biology of B cells. Amsterdam: Elsevier. pp. 189–191. ISBN 0-12-053641-2.

- ^ a b Merino Tejero, Elena; Lashgari, Danial; García-Valiente, Rodrigo; Gao, Xuefeng; Crauste, Fabien; Robert, Philippe A.; Meyer-Hermann, Michael; Martínez, María Rodríguez; van Ham, S. Marieke; Guikema, Jeroen E. J.; Hoefsloot, Huub; van Kampen, Antoine H. C. (2020). "Multiscale Modeling of Germinal Center Recapitulates the Temporal Transition From Memory B Cells to Plasma Cells Differentiation as Regulated by Antigen Affinity-Based Tfh Cell Help". Frontiers in Immunology. 11 620716. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.620716. PMC 7892951. PMID 33613551.

- ^ Glader B, Greer JG, Foerster J, Rodgers GC, Paraskevas F (2008). Wintrobe's Clinical Hematology, 2-Vol. Set. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 347. ISBN 978-0-7817-6507-7.

- ^ a b c d e Walport M, Murphy K, Janeway C, Travers PJ (2008). Janeway's immunobiology. New York: Garland Science. pp. 387–388. ISBN 978-0-8153-4123-9.

- ^ a b c Caligaris-Cappio F, Ferrarini M (1997). Human B Cell Populations (Chemical Immunology). Vol. 67. S. Karger AG (Switzerland). pp. 103–104. ISBN 3-8055-6460-0.

- ^ Kierszenbaum AL (2002). Histology and cell biology: an introduction to pathology. St. Louis: Mosby. p. 275. ISBN 0-323-01639-1.

- ^ Slifka MK, Matloubian M, Ahmed R (March 1995). "Bone marrow is a major site of long-term antibody production after acute viral infection". Journal of Virology. 69 (3): 1895–902. doi:10.1128/jvi.69.3.1895-1902.1995. PMC 188803. PMID 7853531.

- ^ Radbruch, Andreas; Muehlinghaus, Gwendolin; Luger, Elke O.; Inamine, Ayako; Smith, Kenneth G. C.; Dörner, Thomas; Hiepe, Falk (October 2006). "Competence and competition: the challenge of becoming a long-lived plasma cell". Nature Reviews Immunology. 6 (10): 741–750. doi:10.1038/nri1886. PMID 16977339.

- ^ Halliley JL, Tipton CM, Liesveld J, Rosenberg AF, Darce J, Gregoretti IV, et al. (July 2015). "Long-Lived Plasma Cells Are Contained within the CD19(-)CD38(hi)CD138(+) Subset in Human Bone Marrow". Immunity. 43 (1): 132–45. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.016. PMC 4680845. PMID 26187412.

- ^ Manz RA, Radbruch A (April 2002). "Plasma cells for a lifetime?". European Journal of Immunology. 32 (4): 923–7. doi:10.1002/1521-4141(200204)32:4<923::aid-immu923>3.0.co;2-1. PMID 11920557.

- ^ Nguyen, Doan C.; Joyner, Chester J.; Sanz, Iñaki; Lee, F. Eun-Hyung (2019-09-11). "Factors Affecting Early Antibody Secreting Cell Maturation Into Long-Lived Plasma Cells". Frontiers in Immunology. 10 2138. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02138. PMC 6749102. PMID 31572364.

- ^ Tangye, Stuart G. (December 2011). "Staying alive: regulation of plasma cell survival". Trends in Immunology. 32 (12): 595–602. doi:10.1016/j.it.2011.09.001. PMID 22001488.

- ^ Cassese G, Arce S, Hauser AE, Lehnert K, Moewes B, Mostarac M, et al. (August 2003). "Plasma cell survival is mediated by synergistic effects of cytokines and adhesion-dependent signals". Journal of Immunology. 171 (4): 1684–90. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1684. PMID 12902466.

- ^ Lemke A, Kraft M, Roth K, Riedel R, Lammerding D, Hauser AE (January 2016). "Long-lived plasma cells are generated in mucosal immune responses and contribute to the bone marrow plasma cell pool in mice". Mucosal Immunology. 9 (1): 83–97. doi:10.1038/mi.2015.38. PMID 25943272.

- ^ Liang, Bin; Hyland, Lisa; Hou, Sam (June 2001). "Nasal-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Is a Site of Long-Term Virus-Specific Antibody Production following Respiratory Virus Infection of Mice". Journal of Virology. 75 (11): 5416–5420. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.11.5416-5420.2001. PMC 114951. PMID 11333927.

- ^ van Laar, Jacob M.; Melchers, Marc; Teng, Y. K. Onno; van der Zouwen, Boris; Mohammadi, Rozbeh; Fischer, Randy; Margolis, Leonid; Fitzgerald, Wendy; Grivel, Jean-Charles; Breedveld, Ferdinand C.; Lipsky, Peter E. (September 2007). "Sustained Secretion of Immunoglobulin by Long-Lived Human Tonsil Plasma Cells". The American Journal of Pathology. 171 (3): 917–927. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2007.070005. PMC 1959503. PMID 17690187.

- ^ Huard, Bertrand; McKee, Thomas; Bosshard, Carine; Durual, Stéphane; Matthes, Thomas; Myit, Samir; Donze, Olivier; Frossard, Christophe; Chizzolini, Carlo; Favre, Christiane; Zubler, Rudolf (2008-07-01). "APRIL secreted by neutrophils binds to heparan sulfate proteoglycans to create plasma cell niches in human mucosa". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 118 (8): 2887–2895. doi:10.1172/JCI33760. PMC 2447926. PMID 18618015.

- ^ Lemke, A; Kraft, M; Roth, K; Riedel, R; Lammerding, D; Hauser, A E (January 2016). "Long-lived plasma cells are generated in mucosal immune responses and contribute to the bone marrow plasma cell pool in mice". Mucosal Immunology. 9 (1): 83–97. doi:10.1038/mi.2015.38. PMID 25943272.

- ^ Slifka MK, Antia R, Whitmire JK, Ahmed R (March 1998). "Humoral immunity due to long-lived plasma cells". Immunity. 8 (3): 363–72. doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80541-5. PMID 9529153.

- ^ DiLillo DJ, Hamaguchi Y, Ueda Y, Yang K, Uchida J, Haas KM, et al. (January 2008). "Maintenance of long-lived plasma cells and serological memory despite mature and memory B cell depletion during CD20 immunotherapy in mice". Journal of Immunology. 180 (1): 361–71. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.361. PMID 18097037.

- ^ Ahuja A, Anderson SM, Khalil A, Shlomchik MJ (March 2008). "Maintenance of the plasma cell pool is independent of memory B cells". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (12): 4802–7. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.4802A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800555105. PMC 2290811. PMID 18339801.

- ^ Longmire RL, McMillan R, Yelenosky R, Armstrong S, Lang JE, Craddock CG (October 1973). "In vitro splenic IgG synthesis in Hodgkin's disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 289 (15): 763–7. doi:10.1056/nejm197310112891501. PMID 4542304.

- ^ Mei HE, Yoshida T, Sime W, Hiepe F, Thiele K, Manz RA, et al. (March 2009). "Blood-borne human plasma cells in steady state are derived from mucosal immune responses". Blood. 113 (11): 2461–9. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-04-153544. PMID 18987362.

- ^ Bohannon C, Powers R, Satyabhama L, Cui A, Tipton C, Michaeli M, et al. (June 2016). "Long-lived antigen-induced IgM plasma cells demonstrate somatic mutations and contribute to long-term protection". Nature Communications. 7 (1) 11826. Bibcode:2016NatCo...711826B. doi:10.1038/ncomms11826. PMC 4899631. PMID 27270306.

- ^ "Plasma cell" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Agarwal, Amit; Ghobrial, Irene M. (2013-03-01). "Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smoldering multiple myeloma: a review of the current understanding of epidemiology, biology, risk stratification, and management of myeloma precursor disease". Clinical Cancer Research. 19 (5): 985–994. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2922. PMC 3593941. PMID 23224402.

External links

[edit]- Histology image: 21001loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- Histology at wadsworth.org