Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

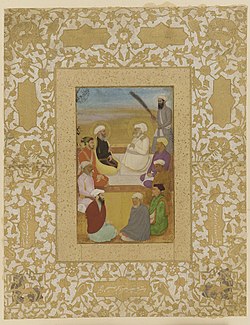

Mian Mir

View on WikipediaThis article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (June 2024) |

Mian Mir or Miyan Mir (c. 1550 – 22 August 1635), was a Sufi Muslim saint who resided in Lahore, in the neighborhood now known as Dharampura.

Key Information

He was a direct descendant of Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab and belonged to the Qadiri order of Sufism. He is famous for being a spiritual instructor of Dara Shikoh, the eldest son of Mughal emperor Shah Jahan.[1][2][3] He is identified as the founder of the Mian Khel branch of the Qadiri order. His younger sister Bibi Jamal Khatun was a disciple of his and a notable Sufi saint in her own right.[1][4][5]

Mian Mir and Emperor Jahangir

[edit]

Mian Mir migrated to and settled in Lahore at the age of 25.[1] He was a friend of God-loving people and he would shun worldly, selfish men, greedy Emirs and ambitious Nawabs who ran after faqirs to get their blessings. To stop such people from coming to see him, Mian Mir posted his mureeds (disciples) at the gate of his house.[6]

Once, Jahangir, the Mughal emperor, with all his retinue came to pay homage to the great faqir. He came with all the pomp and show that befitted an emperor. Mian Mir's sentinels however, stopped the emperor at the gate and requested him to wait until their master had given permission to enter. Jahangir felt slighted. No one had ever dared delay or question his entry to any place in his kingdom. Yet he controlled his temper and composed himself. He waited for permission. After a while, he was ushered into Mian Mir's presence. Unable to hide his wounded vanity, Jahangir, as soon as he entered, told Mian Mir in Persian: Ba dar-e-darvis darbane naa-bayd ("On the doorstep of a faqir, there should be no sentry"). The reply from Mian Mir was, "Babayd keh sage dunia na ayad" (So that selfish men may not enter).[7]

The emperor was embarrassed and asked for forgiveness. Then, with folded hands, Jahangir requested Mian Mir to pray for the success of the campaign which he intended to launch for the conquest of the Deccan. Meanwhile, a poor man entered and, bowing his head to Mian Mir, made an offering of a rupee before him. The Sufi asked the devotee to pick up the rupee and give it to the poorest, neediest person in the audience. The devotee went from one dervish to another but none accepted the rupee. The devotee returned to Mian Mir with the rupee saying: "Master, none of the dervishes will accept the rupee. None is in need, it seems."[7]

"Go and give this rupee to him," said the faqir, pointing to Jahangir. "He is the poorest and most needy of the lot. Not content with a big kingdom, he covets the kingdom of the Deccan. For that, he has come all the way from Delhi to beg. His hunger is like a fire that burns all the more furiously with more wood. It has made him needy, greedy and grim. Go and give the rupee to him."[7]

Mian Mir and Sikhism

[edit]

According to Sikh tradition, the Sikh guru, Guru Arjan Dev, met Mian Mir during their stay in Lahore.[1] This tradition does not appear in the early Sikh literature, and is first mentioned in the 18th and 19th century chronicles.[8]

Legend about foundation of Harmandir Sahib

[edit]According to the Tawarikh-i-Punjab (1848), written by Ghulam Muhayy-ud-Din alias Bute Shah, Mian Mir laid the foundation of the Sikh shrine Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple), at the request of Guru Arjan Dev.[9][10] This is also mentioned in several European sources, beginning with The Punjab Notes and Queries.[11] Even the Report Sri Darbar Sahib (1929), published by the Harmandir Sahib temple authorities, have endorsed this account.[12]

However, this legend is not reported in other historic texts.[13][14] Sakinat al-aulia, a 17th-century biography of Mian Mir compiled by Dara Shikoh, does not mention this account.

Death and legacy

[edit]

After having lived a long life of piety and virtuosity, Mian Mir died on 11 August 1635 at age 84 to 85.[1]

His funeral oration was read by Mughal prince Dara Shikoh, who was a highly devoted disciple of the Saint.[1] There is a hospital named after him in his hometown Lahore, called Mian Mir Hospital.[15]

Tomb

[edit]

He was buried at a place which was about a mile from Lahore near Alamganj, that is at the south-east of the city. Mian Mir's spiritual successor was Mullah Shah Badakhshi.[1] Mian Mir's Mazar (Mausoleum) still attracts hundreds of devotees each day and he is revered by many Sikhs as well as Muslims. The tomb's architecture still remains quite intact to this day. His death anniversary ('Urs' in Urdu language) is observed there by his devotees every year.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g "Profile of Mian Mir". Story of Pakistan website. 4 January 2006. Archived from the original on 5 July 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Hanif, N. (2000). Biographical Encyclopaedia of Sufis: South Asia. Sarup & Sons, New Delhi. ISBN 8176250872. pp. 205–209.

- ^ Larson, Gerald J.; Jacobsen, Knut A. (2005). Theory and practice of yoga: essays in honour of Gerald James Larson (Print). Leiden Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 307, 315. ISBN 9789004147577.

- ^ Rizvi, Saiyid Athar Abbas (1983). A History of Sufism in India. Vol. 2. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 481. ISBN 81-215-0038-9.

- ^ Ernst, Carl W. (1997). The Shambhala Guide to Sufism. Boston: Shambhala. p. 67. ISBN 9781570621802.

- ^ A Sufi, a Sikh and their message of love – A journey from Lahore to Amritsar Dawn newspaper, Updated 20 May 2017, Retrieved 1 December 2023

- ^ a b c KJS Ahluwalia (31 May 2016). "Who was the emperor? Jahangir or Mian Mir?". The Economic Times. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Pashaura Singh (2006). Life and Work of Guru Arjan: History, Memory, and Biography in the Sikh Tradition. Oxford University Press. pp. 126–128. ISBN 978-0-19-908780-8.

- ^ Surindar Singh Kohli. The Sikh and Sikhism. Atlantic. p. 68.

- ^ J.R. Puri and T.R. Shangari. "The life of Bulleh Shah (also talks about Mian Mir laying the foundation of Harmandir Sahib)". Academy of the Punjab in North America website (APNA). Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Madanjit Kaur (1983). The Golden Temple: Past and Present. Department of Guru Nanak Studies, Guru Nanak Dev University Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 9780836413250.

- ^ Pardeep Singh Arshi (1989). The Golden Temple: history, art, and architecture. Harman. p. 10. ISBN 978-81-85151-25-0.

- ^ Louis E. Fenech; W. H. McLeod (2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-4422-3601-1.

- ^ T. N. Madan (2009). Modern Myths, Locked Minds: Secularism and Fundamentalism in India. Oxford University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-19-806510-4.

- ^ Mayor Lahore pays visit to Mian Mir Hospital lahorenews.tv website, Published 19 April 2017, Retrieved 1 December 2023

- ^ Death anniversary of Mian Mir observed in Lahore The Nation newspaper, Published 20 December 2015, Retrieved 1 December 2023

.jpg/250px-Painting_of_the_Sufi_saint_Mian_Mir,_commissioned_by_Dara_Shikoh,_ca.1635_(detail).jpg)

.jpg)