Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Gogaji

View on Wikipedia

| Goga Ji | |

|---|---|

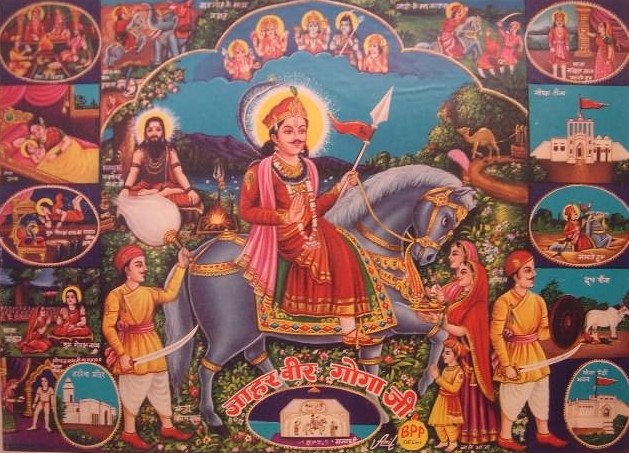

Depiction of Gogaji Maharaj riding his blue horse | |

| Other names | Jaharpeer Chauhan Jaharveer Chauhan |

| Major cult center | Rajasthan, Punjab Region, parts of Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu, Gujarat |

| Abode | Dadrewa Gogamedi |

| Weapon | Spear |

| Mount | Blue horse |

| Festivals | Goga Navami (observed on the ninth day of the Krishna Paksha (waning phase of the moon) in the Hindu month of Bhadrapada) |

| Genealogy | |

| Born | 1003 AD Dadrewa, Churu district, Rajasthan |

| Died | Gogamedi, Hanumangarh district, Rajasthan |

| Parents |

|

Gogaji, also known as Raja Jaharveer Singh Chauhan or Jahirpeer and Bagad Wala, is a folk Hindu deity in the northern India.[1] He is worshipped in the northern states of India especially in Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Uttarakhand, Punjab region, , Jammu and Gujarat.[2] He is a chauhan warrior-hero of the region, venerated as a saint and a protector against snake bites. Although there are references to him in the folklore of Rajasthan, little historical knowledge of Gugga Rana exists other than that he ruled the small kingdom of Dadrewa (in present day Rajasthan) and was a contemporary of Prithviraj Chauhan.[3][4]

Etymology

[edit]According to legend, Gogaji was born in Chauhan clan of Rajputs to the great Chauhan Maharaja Jewar Singh and Rani Bachhal Devi and were rulers of this area during that period – around 900 AD. His desandants adopted the name Bachhil Rajputs after name of Gogaji’s mother.[5][6]

According to one belief, Goga was born with the blessings of Guru Gorakhnath, who gave 'Gugal' fruit (Commiphora wightii) to Goga's mother Bachhal which was used to name him. Another belief is that he was called Goga because of his remarkable service to cows. (Gou in Sanskrit)[7]

Accounts

[edit]

Recorded accounts on Goga vary considerably.[8] The sources do not agree on the time period or who his contemporaries were but he can be placed as living anywhere between the 11th and 14th centuries.[8] According to James Tod, Goga was the chief of the Jangaldesh region and lived during the time of Mahmud of Ghazni in the 10th–11th centuries and was from Bhatinda, who fought with the invader on the bank of the Sutlej.[8] Dashrath Sharma, using Jain sources, such as the Shrawak-Viatudi-Atichar, and the Kyamkhan Rasau, sources from the 15th century, also placed Goga as a contemporary of Mahmud of Ghazni.[8] Pemaram agreed with Sharma and also places him in the same period after evaluating the poetical accounts Gogaji Pirra Chand, Gugapedi, and Gogaji Chauhan ri Nisani.[8] R. C. Temple places him at the time period of Mahmud of Ghazni.[8] William Crooke believed Goga lived in the 13th century and was killed fighting against Firoj Shah of Delhi at the end of the century.[8] Another account states that Goga fought again Ruknuddin Firuz Shah, Sultan of Delhi.[8] Yet another account posits that Goga was a contemporary of Firuz Tughlaq (1351–1388) and fought against Abu Baquer.[8] Most Rajasthani scholars agree with Tod's assessment of placing Goga in the same period of Mahmud of Ghazni century.[8]

According to Chander Shekha, Goga was the Chauhan chief of the region of Dadarewa (present-day Churu district, Rajasthan).[8] He was likely one of the local rulers of northwestern Rajasthan who opposed invaders, similar to Prithviraj Chauhan and Hammirdev, and warred with other north Indian rulers.[8] According to Bankidas, Goga was born to a father named Wacchag while his mother was named Jeevaraj.[8] In western U.P., there is a unique Bijnor version of Goga, which claims he was the son of Prithviraj Chauhan during the Ghurid invasions of the 12th century.[8]

Worship

[edit]He developed into becoming one of the earliest folk-deities in western Rajasthan and preceded Pabuji and Ramdevj.[8] Worship of Goga can be traced to the early 15th century, as a Jain source known as the Sravukavratadi-atichar warns against his worship and other folk-deities by shravaks.[8] The cult of Goga had many shrines, known as thans, with the principal one (gugaji ri medi) being located at Dadarewa, where a celebration dedicated to Goga is held on Bhadrapada (August-September).[8] Another shrine is located at Gogamedi and there are further ones across Marwar.[8] His shrines are associated with the Khejari tree in Marwar.[8]

As a folk-deity, he is worshipped in many forms, such as a snake-god, a cow-protector, a Muslim pir, and as a Nathpandhi Jogi.[8] The Gogaji ra Rasawvala, written in the later part of the 16th century by Vithu Meha, depict Goga as a protector of cows with his relatives Arjan and Sarjan, with him feuding with these relatives over land.[8] Goga developed as a snake-god as the western region of Rajasthan is inhabited by many snakes, with pastoralist and agricultural people fearing being bitten and poisoned by them or their livestock.[8] Thus, Goga came to be seen as a protector against snakes, whose name was chanted by these people to protect against snakes.[8] Depictions of Goga often include snakes in his company, some even depict Goga as a snake.[8] There are religiously syncretic interpretations of Goga, with him being viewed as a Muslim pir or a Nathpanthi Jogi.[8] In the jogi accounts, he is associated with Gorakhnath.[8] Certain Rajputs who converted to Islam, known as Gogawats, viewed him as Zahra Pir, seeing Goga as their ancestor.[8] The cult of Goga and similar saints, such as Ramdevji, had followers from both Hindu and Muslim backgrounds, with them also being connected to Ismailism.[8] Whilst initially Goga was a figure associated with the downtrodden sections of society, namely pastoralists and peasants, after the 18th century his image underwent a process of Rajputization and his legacy was adopted by the ruling-classes, reimagining him as a Rajput hero.[8] He became one of the panch peer quintet.[8] His image also underwent Hinduization until he went from a folk-hero to a Hindu deity that is worshipped across caste and communal lines, especially by lower-castes.[8] Goga had a mount named Javadia, which also became venerated and many horses kept in the places he is worshipped are named after this famous horse.[8] Outside of Rajasthan, Goga is worshipped in Punjab, the Gangetic Plains (western Uttar Pradesh), and Madhya Pradesh.[8] The cult of Goga was prevalent in 19th century Punjab, where he was particular worshipped as a snake-god by Muslims, Hindus, and Sikhs alike.[8]

Kingdom

[edit]Goga had a kingdom called Bagad Dedga that spanned over to Hansi near Hisar in Haryana.[9] It is believed that Goga lived during the 12th Century AD[10] In the past, the river Sutlej flowed through the district of Bathinda in present-day Punjab in India.[11] The capital was at Dadrewa near Ganganagar.

Legends

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2025) |

Family

[edit]Goga (Hindi: गोगा) (Rajasthani: (Gugo) गुग्गो) was born in c. 900 AD to queen Bachchal (the daughter of a ruler, Kanwarpala who in 1173 AD ruled over Sirsa in present-day Haryana) and king Zewar belonging to Chauhan family in the village name Dadrewa in Churu district of Rajasthan.[12] The earliest parts of Goga's life were spent in the village of Dadrewa, situated on Hissar—Bikaner highway in Sadulpur tehsil of Churu district in Rajasthan. According to other legends, his father was Vachha Chauhan, the Raja of Jangal Desh, which stretched from the Sutlej to Haryana.[13]

Birth

[edit]When Bachal was worshipping Gorakhnath, her twin-sister decided to usurp the blessings from the Gorakhnath. In the middle of the night, she wore her sister's clothes and deceived Gorakhnath into giving her the blessing fruit. When Bachal realised it, she rushed to Gorakhnath and said that she had not received anything. To this, Gorakhnath replied that he had already given his blessings and said that her sister was attempting to deceive her. After repeated requests by Bachal, Gorakhnath relented and gave her two Gugal candies. She distributed these candies to ladies having no child, including the 'blue mare' who was pregnant at that time. When the Guru gave the blessing to Bachal, he foretold that her son would become very powerful and would rule over the other two sons of their aunt, Kachal.

Marriage

[edit]1)Goga was married to Kelam de who was daughter of Buda singh ji rathore King of kolu,Rajasthan.

2)Rani Siriyal

Other

[edit]Another story is that Arjan and Sarjan were against Goga and was a part of conspiracy with king Anangpal Tomar of Delhi. King Anganpal attacked bagad region with Arjan and Sarjan. Both of them were killed by Goga. Goga spared the king after his miserere. In a quarrel about land he killed his two brothers on which account he drew upon himself the anger of his mother.[12]

Celebration and fairs

[edit]The history of Goga falls within folk religion and therefore his followers include people from all faiths. Goga is popular as a Devta who protects his followers from snakes and other evils. He has been deified as a snake demigod and is a prominent figure among those who follow the Nāga cult in what is now Rajasthan and since the seventeenth century has been worshipped in the Western Himalayas also, possibly as a consequence of migration there from Rajasthan.[14]

He is particularly popular among those engaged in agrarian pursuits, for whom the fear of snakebite is common. Although a Hindu, he has many Muslim devotees and is chiefly considered to be a saint (pir) who had the power to cure the effects of poison (jahar).[15]

He was reputed to be a disciple of Guru Gorakhnath. According to Muslim oral tradition prevalent in Punjab, he learnt the way of entering and leaving solid earth by a Muslim Pir Hazi Rattan of Bathinda.[16][17] Goga is also believed to have lived for some time in Bathinda.[18]

The cult is prevalent in Rajasthan and other states of northern India, including Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh and the north western districts of Uttar Pradesh. His followers can also be found in Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh. He also has a number of followers in the Jammu district of J&K state.

Rajasthan

[edit]His shrine, referred as madi (shortened colloquial term for Samādhi), consists of a one-room building with a minaret on each corner and a Hindu grave inside, marked by a Nishan (a symbol or sign), which is made up of a long bamboo with peacock plumes, a coconut, some colored threads and some handpankhas with a blue flag on the top.

Worship of Goga starts in Bhaadra month of Hindu calendar. On the 9th of Bhadra, the people worship his symbol, a black snake painted on a wall. Worshippers take a fly-flap, known as chhari, round the village. Devotees pay their respect to it and offer churma. The Savayians sing devotional songs known as ‘Pir ke Solle’ in his honour to the accompaniment of deroos. Beating of deroos is the exclusive privilege of the Savayian community; others may sing, dance or offer charhawa. It is believed that the spirit of Gugga temporarily takes abode in the devotee dancer who lashes himself with a bunch of iron chains. People also open their rakhis on this day(bhadra krishna paksh navmi) and offer them to him. They also offer sweet puri (a type of sweet chappati) and other sweets and take his blessing.

Grand fairs are held at samadhi sathal Gogamedi. Gogamedi is 359 km from Jaipur, in Hanumangarh district of Rajasthan. It is believed that Goga went into samādhi at Gogamedi. Thousands of devotees gather to pay homage at this memorial annually in the month of Bhadrapada during the Goga fair, which lasts for three days. The fair is held from the ninth day of the dark half of Bhadrapada (Goga Navami) to the eleventh day of the dark half of the same month. People sing and dance to the beats of drums with multicoloured flags called nishans in their hands. The songs and bhajans on the life history of Gogaji are recited accompanied by music played with traditional instruments like Damru, Chimta, etc. At his birthplace Dadrewa, the fair goes on over a month. Devotees from far eastern places of Dadrewa start arriving from the beginning of the auspicious month of Bhaadra. These devotees are commonly known as purbia (those who belong to east). It is a common sight to see people with snakes lying around their necks. According to a folklore in and around his birthplace Dadrewa it is believed that if someone picks up even a stick from johra (a barren land which has a sacred pond in Dadrewa), it would turn into a snake. Devotees of Gogaji worship him when they get a snake bite and apply sacred ash (bhabhoot) on the bite as an immediate remedy.

Himachal Pradesh

[edit]In Thaneek Pura, Himachal Pradesh, a very large scale festival and fair is organized on Gugga Navami. The tale of Gugga Ji is recited, from Raksha Bandhan to Gugga Naumi, by the followers who visit every house in the region. These followers while singing the tales of Gugga Ji carry a Chhat (a wooden umbrella) and people offer them grains and other stuff. They bring all the collected offerings to the temple and then the grand festival of Gugga Navami is celebrated for three days. Apart from various pujas and rituals, the wrestling competition (Mall or Dangal) is organized for three days where participants from all over the region compete. The annual three-day fair is also a part of these festivities where people come and enjoy great food, and shop for decorative items, handicrafts, clothes, cosmetics, household goods, and toys for children.

Punjab

[edit]

Goga is known as Gugga in the Punjab who has a significant following. Although Gugga is a deity of Hinduism, he is revered by many Sikhs in the Punjab also. Many Punjabi villages have a shrine dedicated to Gugga Jaharveer known as Medi. A fair is organised annually in many parts of punjab like the village of Hariana in Hoshiarpur district and the village of Chhapar (known as the Chhapar Mela). Gugga's legacy in Punjab can be seen in towns such as Bareta Mandi, which is situated at a distance of 51 km from Mansa in Punjab. "The town is predominantly inhabited by Chauhans who trace their origin from Gugga, ‘Lord of Snakes’. It is said that nobody has ever died here on account of snakebite because of the blessings of Gugga."[19]

In the Punjab region, it is traditional to offer sweet Vermicelli to the shrines of Gugga Ji[20] and sweet fried bread or mathya (Punjabi: ਮੱਥੀਆ). He is worshiped in the month of Bhadon especially on the ninth day of that month. Gugga is meant to protect against snake bites and he is venerated in shrines known as marris. The shrines do not conform to any religion and can range from antholes to structures that resemble a Sikh Gurdwara or a Mosque. When worshipping Gugga, people bring vermicelli (sewai) as offerings and also leave them in places where snakes reside.[16] People perform a devotional dance while dancing on the legendary songs of bravery sung in his praise.[21]

On the day of Gugga Naumi, when offering the sweet dish, songs are sung which include:

ਪੱਲੇ ਮੇਰੇ ਮਥੀਆਂ

ਨੀ ਮੈਂ ਗੁੱਗਾ ਮਨਾਓੁਣ ਚੱਲੀਆਂ

ਨੀ ਮੈਂ ਬਾਰੀ ਗੁੱਗਾ ਜੀ

[20]

Palle mere mathyaa

ni mein Guggaji di puja karn challyaa

ni mein bari Gugga ji

Translation

I have got mathya

I am going to worship Gugga ji

Oh Gugga ji

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ayyappappanikkar (1997). Medieval Indian Literature: Surveys and selections. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-0365-5.

- ^ Experts, EduGorilla Prep. Rajasthan PTET 2024 : Pre-Teacher Education Test (Pre B.Ed Entrance Exam) | 10 Full Mock Tests (2500+ Solved MCQs). EduGorilla Community Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-93-5880-564-2.

- ^ Hāṇḍā, Omacanda (2004). Naga Cults and Traditions in the Western Himalaya. New Delhi: Indus Publishing. p. 330. ISBN 9788173871610. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ^ "Watch: Devotees dance with snakes at Jahar Veer Gogaji fair in Rajasthan's Churu". India Today. 9 September 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2024. “ In Churu, Rajasthan, the traditional Jaharveer Gogaji fair came alive, drawing devoted crowds who displayed their reverence by dancing with snakes. This festival holds significant importance in Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Punjab, and Rajasthan. Gogaji, revered as a peer by both Hindus and Muslims, is seen as a guardian of children. Numerous legends surround his divine birth and his reputed ability to heal snakebite victims.”

- ^ "History". Jai Guga Jahar Veer. 5 December 2014. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

- ^ Kumar, Satendra (21 September 2022). Popular Democracy and the Politics of Caste: Rise of the Other Backward Classes in India. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-68431-5.

- ^ Dalmia, Vasudha; Stietencron, H. von (31 October 1995). Representing Hinduism: The Construction of Religious Traditions and National Identity. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-0-8039-9195-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Shekha, Chander (2022). "A historical and legendary profile of Gogaji, a popular folk deity of medieval Rajasthan" (PDF). International Journal of Applied Research. 8 (12): 141–145.

- ^ Rajasthan [district Gazetteers].: Ganganagar (1972) [1]

- ^ [2] Gupta, Jugal Kishore: History of Sirsa Town

- ^ "Welcome to the official website of the Municipal Corporation Bathinda". Mcbathinda.com. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ a b Sir Henry Miers Elliot; John Beames (1869). Memoirs on the History, Folk-lore, and Distribution of the Races of the North Western Provinces of India: Being an Amplified Edition of the Original Supplemental Glossary of Indian Terms. Trübner & Company. pp. 256–.

- ^ Census of India, 1961: India, Volume 1, Issue 4; Volume 1, Issue 19

- ^ Naga Cults and Traditions in the Western Himalaya: Omacanda Hāṇḍā

- ^ Hāṇḍā, Omacanda (2004). Naga Cults and Traditions in the Western Himalaya. New Delhi: Indus Publishing. pp. 317–320, 330. ISBN 9788173871610. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ^ a b Bhatti, H.S Folk Religion Change and Continuity Rawat Publications

- ^ Shivam Vij 18/01/2013

- ^ James Todd (1920) Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan: Or The Central and Western Rajput States of India, Volume 2 [3]

- ^ "Punjab Revenue". Punjabrevenue.nic.in. 13 April 1992. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ a b Alop ho riha Punjabi virsa – bhag dooja by Harkesh Singh Kehal Unistar Book PVT Ltd ISBN 978-93-5017-532-3

- ^ "Journal of Punjab Studies – Center for Sikh and Punjab Studies – UC Santa Barbara". www.global.ucsb.edu. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

Bibliography

[edit]- Briggs, George Weston (1 January 2001). Gorakhnāth and the Kānphaṭa Yogīs. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 192. ISBN 978-81-208-0564-4. Retrieved 11 January 2011.