Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

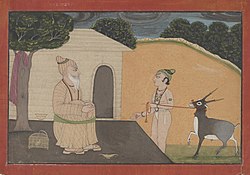

Guru (/ˈɡuːruː/ Sanskrit: गुरु; IAST: guru) is a Sanskrit term for a "mentor, guide, expert, or master" of certain knowledge or field.[1] In pan-Indian traditions, a guru is more than a teacher: traditionally, the guru is a reverential figure to the disciple (or shisya in Sanskrit, literally seeker [of knowledge or truth]) or student, with the guru serving as a "counsellor, who helps mould values, shares experiential knowledge as much as literal knowledge, an exemplar in life, an inspirational source and who helps in the spiritual evolution of a student".[2] Whatever language it is written in, Judith Simmer-Brown says that a tantric spiritual text is often codified in an obscure twilight language so that it cannot be understood by anyone without the verbal explanation of a qualified teacher, the guru.[3] A guru is also one's spiritual guide, who helps one to discover the same potentialities that the guru has already realized.[4]

The oldest references to the concept of guru are found in the earliest Vedic texts of Hinduism.[2] The guru, and gurukula – a school run by guru, were an established tradition in India by the 1st millennium BCE, and these helped compose and transmit the various Vedas, the Upanishads, texts of various schools of Hindu philosophy, and post-Vedic Shastras ranging from spiritual knowledge to various arts so also specific science and technology.[2][5][6] By about mid 1st millennium CE, archaeological and epigraphical evidence suggest numerous larger institutions of gurus existed in India, some near Hindu temples, where guru-shishya tradition helped preserve, create and transmit various fields of knowledge.[6] These gurus led broad ranges of studies including Hindu scriptures, Buddhist texts, grammar, philosophy, martial arts, music and painting.[6][7]

The tradition of the guru is also found in Jainism, referring to a spiritual preceptor, a role typically served by a Jain ascetic.[8][9] In Sikhism, the guru tradition has played a key role since its founding in the 15th century, its founder is referred to as Guru Nanak, and its scripture as Guru Granth Sahib.[10][11] The guru concept has thrived in Vajrayāna Buddhism, where the tantric guru is considered a figure to worship and whose instructions should never be violated.[12][13]

Definition and etymology

[edit]The word guru (Sanskrit: गुरु), a noun, connotes "teacher" in Sanskrit, but in ancient Indian traditions it has contextual meanings with significance beyond what teacher means in English.[2] The guru is more than someone who teaches a specific type of knowledge, and included in the term's scope is someone who is also a "counselor, a sort of parent of mind (Citta) and Self (Atman), who helps mold values (Yamas and Niyamas) and experiential knowledge as much as specific knowledge, an exemplar in life, an inspirational source and who reveals the meaning of life."[2] The word has the same meaning in other languages derived from or borrowing words from Sanskrit, such as Hindi, Marathi, Punjabi, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Odia, Bengali, Gujarati and Nepali. The Malayalam term Acharyan or Asan is derived from the Sanskrit word Acharya.

As a noun the word means the imparter of knowledge (jñāna; also Pali: ñāna). As an adjective, it means 'heavy,' or 'weighty,' in the sense of "heavy with knowledge,"[Note 1] heavy with spiritual wisdom,[15] "heavy with spiritual weight,"[16] "heavy with the good qualities of scriptures and realization,"[17] or "heavy with a wealth of knowledge."[18] The word has its roots in the Sanskrit gri (to invoke, or to praise), and may have a connection to the word gur, meaning 'to raise, lift up, or to make an effort'.[19]

Sanskrit guru is cognate with Latin gravis 'heavy; grave, weighty, serious'[20] and Greek βαρύς barus 'heavy'. All three derive from the Proto-Indo-European root *gʷerə-, specifically from the zero-grade form *gʷr̥ə-.[21]

Darkness and light

[edit]गुशब्दस्त्वन्धकारः स्यात् रुशब्दस्तन्निरोधकः ।

अन्धकारनिरोधित्वात् गुरुरित्यभिधीयते ॥ १६॥

The syllable gu means darkness, the syllable ru, he who dispels them,

Because of the power to dispel darkness, the guru is thus named.

— Advayataraka Upanishad (100 BCE–300 CE), Verse 16.[22][23]

A popular etymological theory considers the term "guru" to be based on the syllables gu (गु) and ru (रु), which it claims stands for darkness and "light that dispels it", respectively.[Note 2] The guru is seen as the one who "dispels the darkness of ignorance."[Note 3][Note 4][26]

Reender Kranenborg disagrees, stating that darkness and light have nothing to do with the word guru. He describes this as a folk etymology.[Note 5]

Joel Mlecko states, "Gu means ignorance, and Ru means dispeller," with guru meaning the one who "dispels ignorance, all kinds of ignorance", ranging from spiritual to skills such as dancing, music, sports and others.[2] Karen Pechilis states that, in the popular parlance, the "dispeller of darkness, one who points the way" definition for guru is common in the Indian tradition.[28]

In Western Esotericism and the Science of Religion, Pierre Riffard makes a distinction between "occult" and "scientific" etymologies, citing as an example of the former the etymology of 'guru' in which the derivation is presented as gu ("darkness") and ru ('to push away'); the latter he exemplifies by "guru" with the meaning of 'heavy.'[29]

In Hinduism

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

The Guru is an ancient and central figure in the traditions of Hinduism.[2] Ultimate liberation or moksha and inner perfection is considered achievable in Hinduism with the help of a guru.[2] The Guru can also serve as a teacher of skills, a counselor, one who helps in the realization of one's Self (Atma), who instills values and experiential knowledge, an exemplar, an inspiration and one who helps guide a student's (śiṣya) spiritual development.[2] At a social and religious level, the Guru helps continue the religion and Hindu way of life.[2] Guru thus has a historic, reverential and an important role in the Hindu culture.[2]

Scriptures

[edit]The word Guru is mentioned in the earliest layer of Vedic texts. The hymn 4.5.6 of Rigveda describes the guru as, "the source and inspirer of the knowledge of the Self, the essence of reality," for one who seeks.[30]

In chapter 4.4 within the Chandogya Upanishad, a guru is described as one whom one attains knowledge that matters, the insights that lead to Self-knowledge.[31] Verse 1.2.8 of the Katha Upanisad declares the guru "as indispensable to the acquisition of knowledge."[31] In chapter 3 of Taittiriya Upanishad, human knowledge is described as that which connects the teacher and the student through the medium of exposition, just like a child is the connecting link between the father and the mother through the medium of procreation.[32][33] In the Taittiriya Upanishad, the guru then urges a student to "struggle, discover and experience the Truth, which is the source, stay and end of the universe."[31]

The ancient tradition of reverence for the guru in Hindu scriptures is apparent in 6.23 of the Shvetashvatara Upanishad, which equates the need of reverence and devotion for guru to be the same as for god,[34][35]

The Bhagavad Gita also exemplifies the importance of a guru within Hinduism. Arjuna when faced with the realization of having to wage war with his kin is paralyzed with grief and remorse. Overwhelmed he lays down his weapons and refuses to fight. Despite his intellectual prowess and skill in warfare he finds himself lacking in Dharmic (moral) clarity. At this moment he turns to Krishna for guidance and in essence seeks Krishna as his guru. This interaction exemplifies the importance within the Hindu tradition for a disciple to seek guidance from an experienced spiritual guru.[40] Additionally, other references to the role of a guru in the Bhagavad Gita include verse 4.34 - those who know their subject well are eager for good students, and the student can learn from such a guru through reverence, service, effort and the process of inquiry.[41][42]

Capabilities, role and methods for helping a student

[edit]

The 8th century Hindu text Upadesasahasri of the Advaita Vedanta philosopher Adi Shankara discusses the role of the guru in assessing and guiding students.[43][44] In Chapter 1, he states that teacher is the pilot as the student walks in the journey of knowledge, he is the raft as the student rows. The text describes the need, role and characteristics of a teacher,[45] as follows,

When the teacher finds from signs that knowledge has not been grasped or has been wrongly grasped by the student, he should remove the causes of non-comprehension in the student. This includes the student's past and present knowledge, want of previous knowledge of what constitutes subjects of discrimination and rules of reasoning, behavior such as unrestrained conduct and speech, courting popularity, vanity of his parentage, ethical flaws that are means contrary to those causes. The teacher must enjoin means in the student that are enjoined by the Śruti and Smrti, such as avoidance of anger, Yamas consisting of Ahimsa and others, also the rules of conduct that are not inconsistent with knowledge. He [teacher] should also thoroughly impress upon the student qualities like humility, which are the means to knowledge.

The teacher is one who is endowed with the power of furnishing arguments pro and con, of understanding questions [of the student], and remembers them. The teacher possesses tranquility, self-control, compassion and a desire to help others, who is versed in the Śruti texts (Vedas, Upanishads), and unattached to pleasures here and hereafter, knows the subject and is established in that knowledge. He is never a transgressor of the rules of conduct, devoid of weaknesses such as ostentation, pride, deceit, cunning, jugglery, jealousy, falsehood, egotism and attachment. The teacher's sole aim is to help others and a desire to impart the knowledge.

— Adi Shankara, Upadesha Sahasri 1.6[48]

Adi Shankara presents a series of examples wherein he asserts that the best way to guide a student is not to give immediate answers, but posit dialogue-driven questions that enable the student to discover and understand the answer.[49]

Reverence and Guru-Bhakti

[edit]Reverence for the guru is a fundamental principle in Hinduism, as illustrated in the Guru Gita by the following shloka [50]

गुरु ब्रह्मा गुरु विष्णु गुरु देवो महेश्वरः।

गुरु साक्षात् परम ब्रह्म तस्मै श्री गुरुवे नमः।

Transliteration: Guru Brahma, Guru Vishnu, Guru Devo Maheshwara, Guru Sakshat Parabrahma, Tasmai Shri Gurave Namah.

Meaning: This shloka praises the Guru, identifying them as the creator (Brahma), the preserver (Vishnu), and the destroyer (Shiva), ultimately recognizing the Guru as the supreme reality.

— Guru Gita Shloka 22

Other notable examples of devotion to the guru within Hinduism include the religious festival of Guru Purnima.[51][52]

Gurukula and the guru-shishya tradition

[edit]

Traditionally, the Guru would live a simple married life, and accept shishya (student, Sanskrit: शिष्य) where he lived. A person would begin a life of study in the Gurukula (the household of the Guru). The process of acceptance included proffering firewood and sometimes a gift to the guru, signifying that the student wants to live with, work and help the guru in maintaining the gurukul, and as an expression of a desire for education in return over several years.[35][53] At the Gurukul, the working student would study the basic traditional vedic sciences and various practical skills-oriented shastras[54] along with the religious texts contained within the Vedas and Upanishads.[5][55][56] The education stage of a youth with a guru was referred to as Brahmacharya, and in some parts of India this followed the Upanayana or Vidyarambha rites of passage.[57][58][59]

The gurukul would be a hut in a forest, or it was, in some cases, a monastery, called a matha or ashram or sampradaya in different parts of India.[7][60][61] Each ashram had a lineage of gurus, who would study and focus on certain schools of Hindu philosophy or trade,[54][55] also known as the guru-shishya parampara (teacher-student tradition).[5] This guru-driven tradition included arts such as sculpture, poetry and music.[62][63]

Inscriptions from 4th century CE suggest the existence of gurukuls around Hindu temples, called Ghatikas or Mathas, where the Vedas were studied.[64] In south India, 9th century Vedic schools attached to Hindu temples were called Calai or Salai, and these provided free boarding and lodging to students and scholars.[65] Archaeological and epigraphical evidence suggests that ancient and medieval era gurukuls near Hindu temples offered wide range of studies, ranging from Hindu scriptures to Buddhist texts, grammar, philosophy, martial arts, music and painting.[6][7]

The guru-shishya parampara, occurs where knowledge is passed down through succeeding generations. It is the traditional, residential form of education, where the Shishya remains and learns with his Guru as a family member.[66][67][68]

Gender and caste

[edit]The Hindu texts offer a conflicting view of whether access to guru and education was limited to men and to certain varna (castes).[69][70] The Vedas and the Upanishads never mention any restrictions based either on gender or varna.[69] The Yajurveda and Atharvaveda texts state that knowledge is for everyone, and offer examples of women and people from all segments of society who are guru and participated in vedic studies.[69][71] The Upanishads assert that one's birth does not determine one's eligibility for spiritual knowledge, only one's effort and sincerity matters.[70]

The early Dharma-sutras and Dharma-sastras, such as Paraskara Grhyasutra, Gautama Smriti and Yajnavalkya smriti, state all four varnas are eligible to all fields of knowledge while verses of Manusmriti state that Vedic study is available only to men of three varnas, unavailable to Shudra and women.[69][70][Note 6] Kramrisch, Scharfe, and Mookerji state that the guru tradition and availability of education extended to all segments of ancient and medieval society.[63][74][75] Lise McKean states the guru concept has been prevalent over the range of class and caste backgrounds, and the disciples a guru attracts come from both genders and a range of classes and castes.[76] During the bhakti movement of Hinduism, which started in about mid 1st millennium CE, the gurus included women and members of all varna.[77][78][79]

Attributes

[edit]The Advayataraka Upanishad states that the true teacher is a master in the field of knowledge, is well-versed in the Vedas, is free from envy, knows yoga, lives the simple life of a yogi, and has realized the knowledge of the Atman (Self).[80] Some scriptures and gurus have warned against false teachers, and have recommended that the spiritual seeker test the guru before accepting him. Swami Vivekananda said that there are many incompetent gurus, and that a true guru should understand the spirit of the scriptures, have a pure character and be free from sin, and should be selfless, without desire for money and fame.[81]

According to the Indologist Georg Feuerstein, in some traditions of Hinduism, when one reaches the state of Self-knowledge, one's own Self becomes the guru.[80] In Tantra, states Feuerstein, the guru is the "ferry who leads one across the ocean of existence."[82] A true guru guides and counsels a student's spiritual development because, states Yoga-Bija, endless logic and grammar leads to confusion, and not contentment.[82] However, various Hindu texts caution prudence and diligence in finding the right guru, and avoiding the wrong ones.[83] For example, in Kula-Arnava text states the following guidance:

Gurus are as numerous as lamps in every house. But, O-Goddess, difficult to find is a guru who lights up everything like a sun.

Gurus who are proficient in the Vedas, textbooks and so on are numerous. But, O Goddess, difficult to find is a guru who is proficient in the supreme Truth.

Gurus who rob their disciples of their wealth are numerous. But, O Goddess, difficult to find is a guru who removes the disciples' suffering.

Numerous here on earth are those who are intent on social class, stage of life and family. But he who is devoid of all concerns is a guru difficult to find.

An intelligent man should choose a guru by whom supreme Bliss is attained, and only such a guru and none other.

— Kula-Arnava, 13.104 - 13.110, Translated by Georg Feuerstein[83]

A true guru is, asserts Kula-Arnava, one who lives the simple virtuous life he preaches, is stable and firm in his knowledge, master yogi with the knowledge of Self (Atma Gyaan) and Brahman (ultimate reality).[83] The guru is one who initiates, transmits, guides, illuminates, debates and corrects a student in the journey of knowledge and of self-realization.[84] The attribute of the successful guru is to help make the disciple into another guru, one who transcends him, and becomes a guru unto himself, driven by inner spirituality and principles.[84]

In modern Hinduism

[edit]In modern neo-Hinduism, Kranenborg states guru may refer to entirely different concepts, such as a spiritual advisor, or someone who performs traditional rituals outside a temple, or an enlightened master in the field of tantra or yoga or eastern arts who derives his authority from his experience, or a reference by a group of devotees of a sect to someone considered a god-like Avatar by the sect.[27]

The tradition of reverence for guru continues in several denominations within modern Hinduism, but rather than being considered as a prophet, the guru is seen as a person who points the way to spirituality, oneness of being, and meaning in life.[85][86][88]

In Buddhism

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

In some forms of Buddhism, states Rita Gross, the concept of Guru is of supreme importance.[89] Guru is called as Garu in Pali. The Guru is the teacher, who teaches the spiritual and religious knowledge. Guru can be anyone who teach this knowledge and not generally need to be Acariya or Upajjhaya. Guru can also be a personal teacher. Buddha is called as Lokagaru, meaning "the teacher of the world".

In Vajrayana Buddhism's Tantric teachings, the rituals require the guidance of a guru.[12] The guru is considered essential and to the Buddhist devotee, the guru is the "enlightened teacher and ritual master", states Stephen Berkwitz.[12] The guru is known as the vajra guru (literally "diamond guru").[90] Initiations or ritual empowerments are necessary before the student is permitted to practice a particular tantra, in Vajrayana Buddhist sects found in Tibet and South Asia.[12] The tantras state that the guru is equivalent to Buddha, states Berkwitz, and is a figure to worship and whose instructions should never be violated.[12][13][91]

The guru is the Buddha, the guru is the Dhamma, and the guru is the Sangha. The guru is the glorious Vajradhara, in this life only the guru is the means [to awakening]. Therefore, someone wishing to attain the state of Buddhahood should please the guru.

— Guhyasanaya Sadhanamala 28, 12th-century[12]

There are Four Kinds of Lama (Guru) or spiritual teacher[92] (Tib. lama nampa shyi) in Tibetan Buddhism:

- gangzak gyüpé lama — the individual teacher who is the holder of the lineage

- gyalwa ka yi lama — the teacher which is the word of the buddhas

- nangwa da yi lama — the symbolic teacher of all appearances

- rigpa dön gyi lama — the absolute teacher, which is rigpa, the true nature of mind

In various Buddhist traditions, there are equivalent words for guru, which include Shastri (teacher), Kalyana Mitra (friendly guide, Pali: Kalyāṇa-mittatā), Acarya (master), and Vajra-Acarya (hierophant).[93] The guru is literally understood as "weighty", states Alex Wayman, and it refers to the Buddhist tendency to increase the weight of canons and scriptures with their spiritual studies.[93] In Mahayana Buddhism, a term for Buddha is Bhaisajya guru, which refers to "medicine guru", or "a doctor who cures suffering with the medicine of his teachings".[94][95]

In Jainism

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

Guru is the spiritual preceptor in Jainism, and typically a role served by Jain ascetics.[8][9] The guru is one of three fundamental tattva (categories), the other two being dharma (teachings) and deva (divinity).[96] The guru-tattva is what leads a lay person to the other two tattva.[96] In some communities of the Śvētāmbara sect of Jainism, a traditional system of guru-disciple lineage exists.[97]

The guru is revered in Jainism ritually with Guru-vandan or Guru-upashti, where respect and offerings are made to the guru, and the guru sprinkles a small amount of vaskep (a scented powder mixture of sandalwood, saffron, and camphor) on the devotee's head with a mantra or blessings.[98]

In Sikhism

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Sikhism |

|---|

|

In Sikhism, seeking a Guru (Gurmukhi: ਗੁਰੂ gurū) is of the utmost importance,[99] Guru Nanak writes in Ang (ਅੰਗ):751 (੫੧ of the Guru Granth Sahib:

ਗਾਫਲ ਗਿਆਨ ਵਿਹੂਣਿਆ ਗੁਰ ਬਿਨੁ ਗਿਆਨੁ ਨ ਭਾਲਿ ਜੀਉ ॥ O foolish mind, without seeking a Guru, loving devotion with the Almighty is not possible.

Guru Amar Das, the third Sikh Guru, says knowledge will have no foundation without a Guru.[100]

The Guru is the source of all knowledge which is Almighty. In Chaupai Sahib, Guru Gobind Singh states about who is the Guru:[101]

ਜਵਨ ਕਾਲ ਜੋਗੀ ਸ਼ਿਵ ਕੀਯੋ ॥ ਬੇਦ ਰਾਜ ਬ੍ਰਹਮਾ ਜੂ ਥੀਯੋ ॥

ਜਵਨ ਕਾਲ ਸਭ ਲੋਕ ਸਵਾਰਾ ॥ ਨਮਸ਼ਕਾਰ ਹੈ ਤਾਹਿ ਹਮਾਰਾ ॥੩੮੪॥

ਜਵਨ ਕਾਲ ਸਭ ਜਗਤ ਬਨਾਯੋ॥ ਦੇਵ ਦੈਤ ਜੱਛਨ ਉਪਜਾਯੋ ॥

ਆਦਿ ਅੰਤਿ ਏਕੈ ਅਵਤਾਰਾ॥ ਸੋਈ ਗੁਰੂ ਸਮਝਿਯਹੁ ਹਮਾਰਾ ॥੩੮੫॥

The Temporal Lord, who created Shiva, the Yogi; who created Brahma, the Master of the Vedas;

The Temporal Lord who fashioned the entire world; I salute the same Lord.

The Temporal Lord, who created the whole world; who created angels, demons and yakshas;

He is the only one form the beginning to the end; I consider Him only my Guru.

The Sikh gurus were fundamental to the Sikh religion, however the concept in Sikhism differs from other usages. The Punjabi word Sikh derives from the Sanskrit word shishya, or disciple and is all about the relationship between the teacher and a student.[102] The concept of Guru in Sikhism stands on two pillars i.e. Miri-Piri (ਮੀਰੀ-ਪੀਰੀ). 'Piri' means spiritual authority and 'Miri' means temporal authority.[103] Traditionally, the concept of Guru is considered central in Sikhism, and its main scripture is prefixed as a Guru, called Guru Granth Sahib, the words therein called Gurbani.[11]

In Western culture

[edit]As an alternative to established religions in the West, some people in Europe and the US looked to spiritual guides and gurus from India and other countries. Gurus from many denominations traveled to Western Europe and the US and established followings.

In particular during the 1960s and 1970s many gurus acquired groups of young followers in Western Europe and the US. According to the American sociologist David G. Bromley this was partially due to the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1965 which permitted Asian gurus entrance to the US.[104] According to the Dutch Indologist Albertina Nugteren, the repeal was only one of several factors and a minor one compared with the two most important causes for the surge of all things 'Eastern': the post-war cross-cultural mobility and the general dissatisfaction with established Western values.[105]

In the Western world, the term is sometimes used in a derogatory way to refer to individuals who have allegedly exploited their followers' naiveté, particularly in certain cults or groups in the fields of hippie, new religious movements, self-help, and tantra.[106] It is also employed more generally for wellness gurus focused on alternative medicine.

According to the professor in sociology Stephen A. Kent at the University of Alberta and Kranenborg (1974), one of the reasons why in the 1970s young people including hippies turned to gurus was because they found that drugs had opened for them the existence of the transcendental or because they wanted to get high without drugs.[107][108] According to Kent, another reason why this happened so often in the US then, was because some anti-Vietnam War protesters and political activists became worn out or disillusioned of the possibilities to change society through political means, and as an alternative turned to religious means.[108] One example of such group was the Hare Krishna movement (ISKCON) founded by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada in 1966, many of whose followers voluntarily accepted the demanding lifestyle of bhakti yoga on a full-time basis, in stark contrast to much of the popular culture of the time.[Note 7]

Some gurus and the groups they lead attract opposition from the Anti-Cult Movement.[110] According to Kranenborg (1984), Jesus Christ fits the Hindu definition and characteristics of a guru.[111]

Environmental activists are sometimes called "gurus" or "prophets" for embodying a moral or spiritual authority and gathering followers. Examples of environmental gurus are John Muir, Henry David Thoreau, Aldo Leopold, George Perkins Marsh, and David Attenborough. Abidin et al. wrote that environmental gurus "merge the boundaries" between spiritual and scientific authority.[112]

Viewpoints

[edit]Gurus and the Guru-shishya tradition have been criticized and assessed by secular scholars, theologians, anti-cultists, skeptics, and religious philosophers.

Jiddu Krishnamurti, groomed to be a world spiritual teacher by the leadership of the Theosophical Society in the early part of the 20th century, publicly renounced this role in 1929 while also denouncing the concept of gurus, spiritual leaders, and teachers, advocating instead the unmediated and direct investigation of reality.[113]

U. G. Krishnamurti, [no relation to Jiddu], sometimes characterized as a spiritual anarchist, denied both the value of gurus and the existence of any related worthwhile teaching.[114]

Dr. David C. Lane proposes a checklist consisting of seven points to assess gurus in his book, Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical. One of his points is that spiritual teachers should have high standards of moral conduct and that followers of gurus should interpret the behavior of a spiritual teacher by following Ockham's razor and by using common sense, and, should not naively use mystical explanations unnecessarily to explain immoral behavior. Another point Lane makes is that the bigger the claim a guru makes, such as the claim to be God, the bigger the chance is that the guru is unreliable. Dr. Lane's fifth point is that self-proclaimed gurus are likely to be more unreliable than gurus with a legitimate lineage.[115]

Highlighting what he sees as the difficulty in understanding the guru from Eastern tradition in Western society, Indologist Georg Feuerstein writes in the chapter Understanding the Guru in his book The Deeper Dimension of Yoga: Theory and practice: "The traditional role of the guru, or spiritual teacher, is not widely understood in the West, even by those professing to practice Yoga or some other Eastern tradition entailing discipleship. [...] Spiritual teachers, by their very nature, swim against the stream of conventional values and pursuits. They are not interested in acquiring and accumulating material wealth or in competing in the marketplace, or in pleasing egos. They are not even about morality. Typically, their message is of a radical nature, asking that we live consciously, inspect our motives, transcend our egoic passions, overcome our intellectual blindness, live peacefully with our fellow humans, and, finally, realize the deepest core of human nature, the Spirit. For those wishing to devote their time and energy to the pursuit of conventional life, this kind of message is revolutionary, subversive, and profoundly disturbing".[116] In his Encyclopedic Dictionary of Yoga (1990), Dr. Feuerstein writes that the importation of yoga to the West has raised questions as to the appropriateness of spiritual discipleship and the legitimacy of spiritual authority.[80]

A British professor of psychiatry, Anthony Storr, states in his book, Feet of Clay: A Study of Gurus, that he confines the word guru (translated by him as "revered teacher") to persons who have "special knowledge" who tell, referring to their special knowledge, how other people should lead their lives. He argues that gurus share common character traits (e.g. being loners) and that some suffer from a mild form of schizophrenia. He argues that gurus who are authoritarian, paranoid, eloquent, or who interfere in the private lives of their followers are the ones who are more likely to be unreliable and dangerous. Storr also refers to Eileen Barker's checklist to recognize false gurus. He contends that some so-called gurus claim special spiritual insights based on personal revelation, offering new ways of spiritual development and paths to salvation. Storr's criticism of gurus includes the possible risk that a guru may exploit his or her followers due to the authority that he or she may have over them, though Storr does acknowledge the existence of morally superior teachers who refrain from doing so. He holds the view that the idiosyncratic belief systems that some gurus promote were developed during a period of psychosis to make sense of their own minds and perceptions, and that these belief systems persist after the psychosis has gone. Storr notes that gurus generalize their experience to all people. Some of them believe that all humanity should accept their vision, while others teach that when the end of the world comes, only their followers will be saved, and the rest of the people will remain unredeemed. According to him, this ″apparently arrogant assumption″ is closely related and other characteristics of various gurus. Storr applies the term "guru" to figures as diverse as Jesus, Muhammad, Buddha, Gurdjieff, Rudolf Steiner, Carl Jung, Sigmund Freud, Jim Jones and David Koresh.[117]

Rob Preece, a psychotherapist and a practicing Buddhist, writes in The Noble Imperfection that while the teacher/disciple relationship can be an invaluable and fruitful experience, the process of relating to spiritual teachers also has its hazards. He writes that these potential hazards are the result of naiveté amongst Westerners as to the nature of the guru/devotee relationship, as well as a consequence of a lack of understanding on the part of Eastern teachers as to the nature of Western psychology. Preece introduces the notion of transference to explain the manner in which the guru/disciple relationship develops from a more Western psychological perspective. He writes: "In its simplest sense transference occurs when unconsciously a person endows another with an attribute that actually is projected from within themselves." In developing this concept, Preece writes that, when we transfer an inner quality onto another person, we may be giving that person a power over us as a consequence of the projection, carrying the potential for great insight and inspiration, but also the potential for great danger: "In giving this power over to someone else they have a certain hold and influence over us it is hard to resist, while we become enthralled or spellbound by the power of the archetype".[118]

The psychiatrist Alexander Deutsch performed a long-term observation of a small cult, called The Family (not to be confused with Family International), founded by an American guru called Baba or Jeff in New York in 1972, who showed increasingly schizophrenic behavior. Deutsch observed that this man's mostly Jewish followers interpreted the guru's pathological mood swings as expressions of different Hindu deities and interpreted his behavior as holy madness, and his cruel deeds as punishments that they had earned. After the guru dissolved the cult in 1976, his mental condition was confirmed by Jeff's retrospective accounts to an author.[119][120]

Jan van der Lans (1933–2002), a professor of the psychology of religion at the Catholic University of Nijmegen, wrote, in a book commissioned by the Netherlands-based Catholic Study Center for Mental Health, about followers of gurus and the potential dangers that exist when personal contact between the guru and the disciple is absent, such as an increased chance of idealization of the guru by the student (myth making and deification), and an increase of the chance of false mysticism. He further argues that the deification of a guru is a traditional element of Eastern spirituality but, when detached from the Eastern cultural element and copied by Westerners, the distinction between the person who is the guru and that which he symbolizes is often lost, resulting in the relationship between the guru and disciple degenerating into a boundless, uncritical personality cult.[Note 8]

In their 1993 book, The Guru Papers, authors Diana Alstad and Joel Kramer reject the guru-disciple tradition because of what they see as its structural defects. These defects include the authoritarian control of the guru over the disciple, which is in their view increased by the guru's encouragement of surrender to him. Alstad and Kramer assert that gurus are likely to be hypocrites because, in order to attract and maintain followers, gurus must present themselves as purer than and superior to ordinary people and other gurus.[123]

According to the journalist Sacha Kester, in a 2003 article in the Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant, finding a guru is a precarious matter, pointing to the many holy men in India and the case of Sathya Sai Baba whom Kester considers a swindler. In this article he also quotes the book Karma Cola describing that in this book a German economist tells author Gita Mehta, "It is my opinion that quality control has to be introduced for gurus. Many of my friends have become crazy in India". She describes a comment by Suranya Chakraverti who said that some Westerners do not believe in spirituality and ridicule a true guru. Other westerners, Chakraverti said, on the other hand believe in spirituality but tend to put faith in a guru who is a swindler.[124]

See also

[edit]- Lineage

- Lifestyle

- Others

Bibliography

[edit]- Amanda Lucia (2022), The contemporary guru field. Religion Compass.

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Guru: a spiritual master; one who is heavy with knowledge of the Absolute and who removes nescience with the light of the divine."[14]

- ^ "[...] the term is a combination of the two words gu(darkness) and ru (light), so together they mean 'divine light that dispels all darkness.'" [...] "Guru is the light that disperses the darkness of ignorance."[24]

- ^ "The etymological derivation of the word guru is in this verse from Guru Gita: 'The root gu stands for darkness; ru for its removal. The removal of the darkness of ignorance in the heart is indicated by the word "guru'" (Note: Guru Gita is a spiritual text in the Markandeya Purana, in the form of a dialog between Siva and Parvati on the nature of the guru and the guru/disciple relationship.) [...] the meanings of gu and ru can also be traced to the Panini-sutras gu samvarane and ru himsane, indicating concealment and its annulment."[25]

- ^ "Guru: remover of darkness, bestower of light'"[25]

- ^ Dutch original: "a. De goeroe als geestelijk raadsman Als we naar het verschijnsel goeroe in India kijken, kunnen we constateren dat er op zijn minst vier vormen van goeroeschap te onderscheiden zijn. De eerste vorm is die van de 'geestelijk raadsman'. Voordat we dit verder uitwerken eerst iets over de etymologie. Het woord goeroe komt uit het Sanskriet, wordt geschreven als 'guru' en betekent 'zwaar zijn', 'gewichtig zijn', vooral in figuurlijk opzicht. Zo krijgt het begrip 'guru' de betekenis van 'groot', 'geweldig' of 'belangrijk', en iets verdergaand krijgt het aspecten van 'eerbiedwaardig' en 'vererenswaardig'. Al vrij snel word dit toegepast op de 'geestelijk leraar'. In allerlei populaire literatuur, ook in India zelf, wordt het woord 'guru' uiteengelegd in 'gu' en 'ru', als omschrijvingen voor licht en duister; de goeroe is dan degene die zijn leerling uit het materiële duister overbrengt naar het geestelijk licht. Misschien doe een goeroe dat ook inderdaad, maar het heeft niets met de betekenis van het woord te maken, het is volksetymologie."

English translation "a. The guru as spiritual adviser: If we look at the phenomenon of gurus in India then we can see that there are at least four forms of guruship that can be distinguished. The first form is that of the "spiritual adviser." Before we will elaborate on this, first something about the etymology. The word guru comes from Sanskrit, is written as 'guru' and connotes philosophically 'being heavy' or 'being weighty'. In that way, the concept of guru gets the meaning of 'big', 'great', or 'important' and somewhat further it also gets aspects of 'respectable' and 'honorable'. Soon it is applied to the 'spiritual adviser'. In various popular literature, in India herself too, the word 'guru' is explained in the parts 'gu' and 'ru', as descriptions for light and darkness: the guru is then the person who bring the student from the material darkness into the spiritual light. A guru may indeed do that, but it has nothing to do with the meaning of the word, it is folk etymology."[27] - ^ Patrick Olivelle notes the modern doubts about the reliability of Manusmriti manuscripts. He writes, "Manusmriti was the first Indian legal text introduced to the western world through the translation of Sir William Jones in 1794. (...) This was based on the Calcutta manuscript with the commentary of Kulluka. It was Kulluka's version that has been assumed to be the original [vulgate version] and translated repeatedly from Jone (1794) and Doniger (1991). The belief in the authenticity of Kulluka's text was openly articulated by Burnell. This is far from the truth. Indeed, one of the great surprises of my editorial work has been to discover how few of the over 50 manuscripts that I collated actually follow the vulgate in key readings."[72]

Sinha writes, in case of Manusmriti, that "certain verses discouraged, but others allowed women to read Vedic scriptures."[73] - ^ "Devotees don't have such an easy time. They who choose to live in the temples – now a very small minority -chant the Hare Krishna mantra 1,728 time a day. […] Those living in an ashram – far fewer than in the 1970s – have to get up at 4am for worship. All members have to give up meat, fish and eggs; alcohol, tobacco, drugs, tea and coffee; gambling, sports, games and novels; and sex except for procreation with marriage […] It's a demanding lifestyle. Outsiders may wonder why people join."[109]

- ^ "Wat Van der Lans hier signaleert, is het gevaar dat de goeroe een instantie van absolute overgave en totale overdracht wordt. De leerling krijgt de gelegenheid om zijn grootheidsfantasieën op de goeroe te projecteren, zonder dat de goeroe daartegen als kritische instantie kan optreden. Het lijkt er zelfs vaak eerder op dat de goeroe in woord, beeld en geschrift juist geneigd is deze onkritische houding te stimuleren. Dit geldt zeker ook voor goeroe Maharaji, maar het heeft zich -gewild en ongewild ook voorgedaan bij Anandamurti en Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. [..] De vergoddelijking van de goeroe is 'een traditioneel element in de Oosterse spiritualiteit, maar, losgemaakt, uit dit cultuurmilieu en overgenomen door Westerse mensen, gaat het onderscheid vaak verloren tussen de persoon van de goeroe en dat wat hij symboliseert en verwordt tot een kritiekloze persoonlijkheidsverheerlijking' (Van der Lans 1981b, 108)"[121][122]

References

[edit]- ^ Pertz, Stefan (2013). The Guru in smiti - Critical Perspectives on Management. GRIN Verlag. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-3638749251.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Mlecko, Joel D. (1982). "The Guru in Hindu Tradition". Numen. 29 (1). Brill: 33–61. doi:10.1163/156852782x00132. ISSN 0029-5973. JSTOR 3269931.

- ^ Simmer-Brown, Judith (2002). Dakini's Warm Breath: The Feminine Principle in Tibetan Buddhism. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambhala Publications. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-57062-920-4.

- ^ "Guru". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2013.

- ^ a b c Tamara Sears (2014), Worldly Gurus and Spiritual Kings: Architecture and Asceticism in Medieval India, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0300198447, pages 12-23, 27-28, 73-75, 187-230

- ^ a b c d Hartmut Scharfe (2002), "From Temple schools to Universities", in Education in Ancient India: Handbook of Oriental Studies, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-9004125568, page 176-182

- ^ a b c George Michell (1988), The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to Its Meaning and Forms, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226532301, pages 58-60

- ^ a b Jeffery D Long (2009), Jainism: An Introduction, IB Tauris, ISBN 978-1845116262, pages 110, 196

- ^ a b Christopher Partridge (2013), Introduction to World Religions, Augsburg Fortress, ISBN 978-0800699703, page 252

- ^ William Owen Cole (1982), The Guru in Sikhism, Darton Longman & Todd, ISBN 9780232515091, pages 1-4

- ^ a b HS Singha & Satwant Kaur, Sikhism, A Complete Introduction, Hemkunt Press, ISBN 81-7010-245-6, pages 21-29, 54-55

- ^ a b c d e f Stephen Berkwitz (2009), South Asian Buddhism: A Survey, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415452496, pages 130-133

- ^ a b William Johnston (2013), Encyclopedia of Monasticism, Routledge, ISBN 978-1579580902, page 371

- ^ Tirtha Goswami Maharaj, A Taste of Transcendence, (2002) p. 161, Mandala Press. ISBN 1-886069-71-9.

- ^ Lipner, Julius J.,Their Religious Beliefs and Practices p.192, Routledge (UK), ISBN 0-415-05181-9

- ^ Cornille, C. The Guru in Indian Catholicism (1991) p.207. Peeters Publishers ISBN 90-6831-309-6

- ^ Hopkins, Jeffrey Reflections on Reality (2002) p. 72. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21120-0

- ^ Varene, Jean. Yoga and the Hindu Tradition (1977). p.226. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-85116-8

- ^ Lowitz, Leza A. (2004). Sacred Sanskrit Words. Stone Bridge Press. p. 85. 1-880-6568-76.

- ^ Barnhart, Robert K. (1988). The Barnhart Dictionary of Etymology. H.W. Wilson Co. p. 447. ISBN 978-0-8242-0745-8.

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.). Houghton Mifflin. 2000. p. 2031. ISBN 978-0-395-82517-4.

- ^ Advayataraka Upanishad with Commentaries Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, Verse 16, Sanskrit

- ^ G Feuerstein (1989), Yoga, Tarcher, ISBN 978-0874775259, pages 240-243

- ^ Murray, Thomas R. Moral Development Theories - Secular and Religious: A Comparative Study. (1997). p. 231. Greenwood Press.

- ^ a b Grimes, John. A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English. (1996) p.133. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-3067-7

- ^ Krishnamurti, J. The Awakening of Intelligence. (1987) p.139. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-064834-1

- ^ a b Kranenborg, Reender (Dutch language) Neohindoeïstische bewegingen in Nederland : een encyclopedisch overzicht page 50 (En: Neo-Hindu movements in the Netherlands, published by Kampen Kok cop. (2002) ISBN 90-435-0493-9 Kranenborg, Reender (Dutch language) Neohindoeïstische bewegingen in Nederland : een encyclopedisch overzicht (En: Neo-Hindu movements in the Netherlands, published by Kampen Kok cop. (2002) ISBN 90-435-0493-9 page 50

- ^ Karen Pechilis (2004), The Graceful Guru, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195145373, pages 25-26

- ^ Riffard, Pierre A. in Western Esotericism and the Science of Religion Faivre A. & Hanegraaff W. (Eds.) Peeters Publishers( 1988), ISBN 90-429-0630-8

- ^ Sanskrit original: इदं मे अग्ने कियते पावकामिनते गुरुं भारं न मन्म । बृहद्दधाथ धृषता गभीरं यह्वं पृष्ठं प्रयसा सप्तधातु ॥६॥ – Rigveda 4.5.6 Wikisource

English Translation: Joel Mlecko (1982), The Guru in Hindu Tradition Numen, Volume 29, Fasc. 1, page 35 - ^ a b c English Translation: Joel Mlecko (1982), The Guru in Hindu Tradition Numen, Volume 29, Fasc. 1, pages 35-36

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 222-223

- ^ Taittiriya Upanishad SS Sastri (Translator), The Aitereya and Taittiriya Upanishad, pages 65-67

- ^ Robert Hume (1921), Shvetashvatara Upanishad 6.23, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, page 411

- ^ a b Joel Mlecko (1982), The Guru in Hindu Tradition Numen, Volume 29, Fasc. 1, page 37

- ^ Shvetashvatara Upanishad 6.23 Wikisource

- ^ Paul Carus, The Monist at Google Books, pages 514-515

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 326

- ^ Max Muller, Shvetashvatara Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part II, Oxford University Press, page 267

- ^ Eknath, Easwaran, ed. (2007). The Bhagavad Gita. The classics of Indian spirituality (2nd ed.). Tomales, CA: Nilgiri Press. pp. Chapter 2. ISBN 978-1-58638-019-9.

- ^ Christopher Key Chapple (Editor) and Winthrop Sargeant (Translator), The Bhagavad Gita: Twenty-fifth–Anniversary Edition, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-1438428420, page 234

- ^ Jeaneane D. Fowler (2012), The Bhagavad Gita, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1845193461, page 87

- ^ Śaṅkarācārya; Sengaku Mayeda (1979). A Thousand Teachings: The Upadeśasāhasrī of Śaṅkara. SUNY Press. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-0-7914-0944-2. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ^ Knut A. Jacobsen (1 January 2008). Theory and Practice of Yoga : 'Essays in Honour of Gerald James Larson. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-81-208-3232-9. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ^ Śaṅkarācārya; Sengaku Mayeda (2006). A Thousand Teachings: The Upadeśasāhasrī of Śaṅkara. SUNY Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-8120827714.

- ^ Sanskrit: शिष्यस्य ज्ञानग्रहणं च लिन्गैर्बुद्ध्वा तदग्रहणहेतूनधर्म लौकिकप्रमादनित्यानित्य(वस्तु) विवेकविषयासञ्जातदृढपूर्वश्रुतत्व-लोक-चिन्तावेक्षण-जात्याद्यभिमानादींस्तत्प्रतिपक्षैः श्रुतिस्मृतिविहितैरपनयेदक्रोधादिभिरहिंसादिभिश्च यमैर्ज्ञानाविरुद्धैश्च नियमैः ॥ ४॥ अमानित्वादिगुणं च ज्ञानोपायं सम्यग् ग्राहयेत् ॥ ५॥ Source;

English Translation 1: S Jagadananda (Translator, 1949), Upadeshasahasri, Vedanta Press, ISBN 978-8171200597, pages 3-4; OCLC 218363449

English Translation 2: Śaṅkarācārya; Sengaku Mayeda (2006). A Thousand Teachings: The Upadeśasāhasrī of Śaṅkara. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-8120827714. - ^ Karl Potter (2008), Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies Vol. III, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120803107, pages 218-219

- ^ S Jagadananda (Translator, 1949), Upadeshasahasri, Vedanta Press, ISBN 978-8171200597, page 5; OCLC 218363449

English Translation 2: Śaṅkarācārya; Sengaku Mayeda (2006). A Thousand Teachings: The Upadeśasāhasrī of Śaṅkara. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-8120827714. - ^ Sanskrit: Upadesha sahasri;

English Translation: S Jagadananda (Translator, 1949), Upadeshasahasri, Vedanta Press, ISBN 978-8171200597, prose section, page 43; OCLC 218363449 - ^ Griffin, Mark (2011). Shri Guru Gita (2nd ed.). Hard Light Center of Awakening. ISBN 978-0-975902-07-3.

- ^ "Guru Purnima: Know the date, origin, theme and significance; all you need to know". The Indian Express. 2024-07-20. Retrieved 2024-10-13.

- ^ "Guru Purnima 2024: Date, Auspicious Times, And Traditional Prasad Recipe". NDTV.com. Retrieved 2024-10-13.

- ^ Ludo Rocher (2003), The Dharmaśāstas, in The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism (Editor: Gavin Flood), Blackwell Publishing Oxford, ISBN 0-631-21535-2, page 102-104

- ^ a b Stella Kramrisch (1958), Traditions of the Indian Craftsman, The Journal of American Folklore, Volume 71, Number 281, Traditional India: Structure and Change (Jul. - Sep., 1958), pages 224-230

- ^ a b Samuel Parker (1987), Artistic practice and education in India: A historical overview, Journal of Aesthetic Education, pages 123-141

- ^ Misra, R. N. (2011), Silpis in Ancient India: Beyond their Ascribed Locus in Ancient Society, Social Scientist, Vol. 39, No. 7/8, pages 43-54

- ^ Mary McGee (2007), Samskara, in The Hindu World (Editors: Mittal and Thursby), Routledge, ISBN 978-0415772273, pages 332-356;

Kathy Jackson (2005), Rituals and Patterns in Children's Lives, University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 978-0299208301, page 46 - ^ PV Kane, Samskara, Chapter VII, History of Dharmasastras, Vol II, Part I, Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, pages 268-287

- ^ V Narayanan (Editors: Harold Coward and Philip Cook, 1997), Religious Dimensions of Child and Family Life, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, ISBN 978-1550581041, page 67

- ^ Gavin Flood (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521438780, pages 133-135

- ^ Hartmut Scharfe (2002), From Temple schools to Universities, in Education in Ancient India: Handbook of Oriental Studies, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-9004125568, pages 173-174

- ^ Winand Callewaert and Mukunda Lāṭh (1989), The Hindi Songs of Namdev, Peeters Publishers, ISBN 978-906831-107-5, pages 57-59

- ^ a b Stella Kramrisch (1994), Exploring India's Sacred Art (Editor: Barbara Miller), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120812086, pages 59-66

- ^ Hartmut Scharfe (2002), "From Temple schools to Universities", in Education in Ancient India: Handbook of Oriental Studies, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-9004125568, pages 169-171

- ^ Hartmut Scharfe (2002), "From Temple schools to Universities", in Education in Ancient India: Handbook of Oriental Studies, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-9004125568, page 175

- ^ William Pinch (2012), Warrior Ascetics and Indian Empires, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107406377, pages 37-38, 141-144, 110-117

William Pinch, Peasants and Monks in British India, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0520200616, pages 57-78 - ^ Sunil Kothari and Avinash Pasricha (2001), Kuchipudi, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-8170173595, pages 155-170 and chapter on dance-arts related Guru parampara

- ^ SS Kumar (2010), Bhakti - the Yoga of Love, LIT Verlag, ISBN 978-3643501301, pages 50-51

- ^ a b c d Kotha Satchidanda Murthy (1993), Vedic Hermeneutics, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120811058, pages 14-17

- ^ a b c Arvind Sharma (2000), Classical Hindu Thought: An Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195644418, pages 147-158

- ^ D Chand, Yajurveda, Verses 26.2-26.3, Osmania University, page 270

- ^ Patrick Olivelle (2004), Manu's Code of Law, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195171464, pages 353-354, 356-382

- ^ J Sinha (2014), Psycho-Social Analysis of the Indian Mindset, Springer Academic, ISBN 978-8132218036, page 5

- ^ Hartmut Scharfe (2007), Education in Ancient India: Handbook of Oriental Studies, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-9004125568, pages 75-79, 102-103, 197-198, 263-276

- ^ Radha Mookerji (2011), Ancient Indian Education: Brahmanical and Buddhist, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120804234, pages 174-175, 270-271

- ^ Lise McKean (1996), Divine Enterprise: Gurus and the Hindu Nationalist Movement, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226560106, pages 14-22, 57-58

- ^ John Stratton Hawley (2015), A Storm of Songs: India and the Idea of the Bhakti Movement, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0674187467, pages 304-310

- ^ Richard Kieckhefer and George Bond (1990), Sainthood: Its Manifestations in World Religions, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0520071896, pages 116-122

- ^ Sheldon Pollock (2009), The Language of the Gods in the World of Men, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0520260030, pages 423-431

- ^ a b c Feuerstein, Georg Dr. Encyclopedic dictionary of yoga Published by Paragon House 1st edition (1990) ISBN 1-55778-244-X

- ^ Vivekananda, Swami (1982). Karma-Yoga and Bhakti-Yoga. Oxford: Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center. ISBN 9780911206227.

- ^ a b Georg Feuerstein (1998), Tantra: The Path of Ecstasy, Shambhala Publications, ISBN 978-1570623042, pages 85-87

- ^ a b c Georg Feuerstein (1998), Tantra: The Path of Ecstasy, Shambhala Publications, ISBN 978-1570623042, pages 91-94

- ^ a b Georg Feuerstein (2011), The Deeper Dimension of Yoga: Theory and Practice, Shambhala Publications, ISBN 978-1570629358, pages 127-131

- ^ Ranade, Ramchandra Dattatraya Mysticism in India: The Poet-Saints of Maharashtra, pp.392, SUNY Press, 1983. ISBN 0-87395-669-9

- ^ Mills, James H. and Sen, Satadru (Eds.), Confronting the Body: The Politics of Physicality in Colonial and Post-Colonial India, pp.23, Anthem Press (2004), ISBN 1-84331-032-5

- ^ Poewe, Karla O.; Hexham, Irving (1997). New religions as global cultures: making the human sacred. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. p. 106. ISBN 0-8133-2508-0.

- ^ "Gurus are not prophets who declare the will of God and appeal to propositions found in a Scripture. Rather, they are said to be greater than God because they lead to God. Gurus have shared the essence of the Absolute and experienced the oneness of being, which endows them with divine powers and the ability to master people and things in this world."[87]

- ^ Rita Gross (1993), Buddhism After Patriarchy, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0791414033, page 253

- ^ Strong, John S. (1995). The experience of Buddhism: sources and interpretations. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Pub. Co. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-534-19164-1.

- ^ Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche (2007), Losing the Clouds, Gaining the Sky: Buddhism and the Natural Mind (Editor: Doris Wolter), Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-0861713592, pages 72-76

- ^ "Lama". Rigpa Wiki. Retrieved 2012-12-26.

- ^ a b Alex Wayman (1997), Untying the Knots in Buddhism: Selected Essays, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120813212, pages 206, 205-219

- ^ Alex Wayman (1997), Untying the Knots in Buddhism: Selected Essays, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120813212, pages 208-209

- ^ Paul Williams (1989), Mahāyāna Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415025379, pages 247-249

- ^ a b John Cort (2011), Jains in the World : Religious Values and Ideology in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199796649, page 100

- ^ Peter Fl Gel and Peter Flügel (2006), Studies in Jaina History and Culture, Routledge, ISBN 978-1134235520, pages 249-250

- ^ John Cort (2011), Jains in the World : Religious Values and Ideology in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199796649, pages 111-115

- ^ "iGurbani - Shabad". www.igurbani.com. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ^ "iGurbani - Shabad". www.igurbani.com. p. 650. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ^ Translation 1: Sri Dasam Granth Sahib Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, Verses 384-385, page 22; Translation 2

- ^ Geoffrey Parrinder (1971), World Religions: From Ancient History to the Present, Hamlyn Publishing, page 254, ISBN 978-0-87196-129-7

- ^ E. Marty, Martin; Appleby R. Scott (1996). Fundamentalisms and the State: Remaking Polities, Economies, and Militance. University of Chicago Press. pp. 278. ISBN 978-0226508849.

- ^ Bromley, David G., Ph.D. & Anson Shupe, Ph.D., Public Reaction against New Religious Movements article that appeared in Cults and new religious movements: a report of the Committee on Psychiatry and Religion of the American Psychiatric Association, edited by Marc Galanter, M.D., (1989) ISBN 0-89042-212-5

- ^ Nugteren, Albertina (Tineke) Dr. (Associate professor in the phenomenology and history of Indian religions at the faculty of theology at the university of Tilburg) "Tantric Influences in Western Esotericism", article that appeared at a 1997 CESNUR conference and that was published in the book New Religions in a Postmodern World edited by Mikael Rothstein and Reender Kranenborg RENNER Studies in New religions Aarhus University press, (2003) ISBN 87-7288-748-6

- ^ Gressett, Michael J. (November 2006). Forsthoefel, Thomas A.; Humes, Cynthia Ann (eds.). "Gurus in America". The Journal of Asian Studies. 65 (4). Albany: State University of New York Press: 842–844. doi:10.1017/S0021911806001872.

- ^ Kranenborg, Reender (Dutch language) Zelfverwerkelijking: oosterse religies binnen een westerse subkultuur (En: Self-realization: eastern religions in a Western Sub-culture, published by Kampen Kok (1974)

- ^ a b Kent, Stephen A. Dr. From slogans to mantras: social protest and religious conversion in the late Vietnam war era Syracuse University press ISBN 0-8156-2923-0 (2001)

- ^ Barrett, D. V. The New Believers - A survey of sects, cults and alternative religions 2001 UK, Cassell & Co. ISBN 0-304-35592-5 entry ISKCON page 287,288

- ^ "Anti-Cult Movement | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2020-09-08.

- ^ Kranenborg, Reender (Dutch language) Een nieuw licht op de kerk? Bijdragen van nieuwe religieuze bewegingen voor de kerk van vandaag (En: A new perspective on the church? Contributions of new religious movements for today's church), the Hague Boekencentrum (1984) ISBN 90-239-0809-0 pp 93-99

- ^ Abidin, Crystal; Brockington, Dan; Goodman, Michael K.; Mostafanezhad, Mary; Richey, Lisa Ann (2020-10-17). "The Tropes of Celebrity Environmentalism" (PDF). Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 45 (1): 387–410. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012320-081703. ISSN 1543-5938.

- ^ Jiddu, Krishnamurti (September 1929). "The Dissolution of the Order of the Star: A Statement by J. Krishnamurti". International Star Bulletin 2 [Volumes not numbered in original] (2) [Issues renumbered starting August 1929]: 28-34. (Eerde: Star Publishing Trust). OCLC 34693176. J.Krishnamurti Online. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ Uppaluri Gopala (U. G.) Krishnamurti (2002) (Revised ed.) [Originally published 1982. Goa, India: Dinesh Vaghela Cemetile]. The Mystique of Enlightenment: The Radical Ideas of U.G. Krishnamurti. Arms, Rodney ed. Sentient Publications. Paperback. p. 2. ISBN 0-9710786-1-0. Wikisource. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ Lane, David C. (1994). "Chapter 12: The Spiritual Crucible". Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical. Garland Pub. ISBN 978-0815312758. Archived from the original on 2009-10-27.

- ^ Feuerstein, Georg Dr. The Deeper Dimension of Yoga: Theory and Practice, Shambhala Publications, released on (2003) ISBN 1-57062-928-5

- ^ Storr, Anthony (1996). Feet of Clay; Saints, Sinners, and Madmen: A Study of Gurus. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-684-82818-9.

- ^ Preece, Rob, "The teacher-student relationship" in The Noble Imperfection: The challenge of individuation in Buddhist life, Mudras Publications

- ^ Deutsch, Alexander M.D. Observations on a sidewalk ashram Archive Gen. Psychiatry 32 (1975) 2, 166-175

- ^ Deutsch, Alexander M.D. Tenacity of Attachment to a cult leader: a psychiatric perspective American Journal of Psychiatry 137 (1980) 12, 1569-1573.

- ^ Lans, Jan van der Dr. (Dutch language) Volgelingen van de goeroe: Hedendaagse religieuze bewegingen in Nederland Archived 2005-01-14 at the Wayback Machine, written upon request for the KSGV Archived 2005-02-08 at the Wayback Machine published by Ambo, Baarn, 1981 ISBN 90-263-0521-4

- ^ Schnabel, Paul Dr. (Dutch language) Between stigma and charisma: new religious movements and mental health Erasmus university Rotterdam, Faculty of Medicine, Ph.D. thesis, ISBN 90-6001-746-3 (Deventer, Van Loghum Slaterus, 1982) Chapter V, page 142

- ^ Kramer, Joel, and Diana Alstad The guru papers: masks of authoritarian power (1993) ISBN 1-883319-00-5

- ^ Kester, Sacha "Ticket naar Nirvana"/"Ticket to Nirvana", article in the Dutch Newspaper De Volkskrant 7 January 2003

Further reading

[edit]- Barth, F. (1990). "The Guru and the Conjurer: Transactions in Knowledge and the Shaping of Culture in Southeast Asia and Melanesia". Man. 25 (4): 640–653. doi:10.2307/2803658. JSTOR 2803658.

- Brown, Mick (1998). The Spiritual Tourist. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 1-58234-034-X.

- Copeman, Jacob; Ikegame, Aya (2012). The Guru in South Asia: New Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-51019-6.

- Forsthoefel, Thomas; Humes, Cynthia Ann, eds. (2005). Gurus in America. Albany, New York: SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-6573-8.

- Hara, M. (1979). "Hindu Concepts of Teacher Sanskrit Guru and Ācārya". In Nagatomi, M.; et al. (eds.). Sanskrit and Indian Studies. Studies of Classical India. Vol. 2. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 93–118. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-8941-2_6. ISBN 978-94-009-8943-6.

- Padoux, André (2013). "The Tantric Guru". In White, David Gordon (ed.). Tantra in Practice. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1778-4.

- Pechelis, Karen (2004). The Graceful Guru: Hindu Female Gurus in India and the United States. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514537-3.

- van der Braak, André (2003). Enlightenment Blues: My Years with an American Guru. Monkfish Book Publishing. ISBN 0-9726357-1-8.

- Wayman, Alex (1987). "The Guru in Buddhism". Studia Missionalia. 36. Universita Gregoriana Roma: 195–214.

External links

[edit]- Guru choice and spiritual seeking in contemporary India, M Warrier (2003), International Journal of Hindu Studies, Volume 7, Issue 1–3, pages 31–54

- Guru-shishya relationship in Indian culture: The possibility of a creative resilient framework, MK Raina (2002), Journal: Psychology & Developing Societies

- Mentors in Indian mythology - Guru and Gurukul system, P. Nachimuthu (2006), Management and Labor Studies

- Scandals in emerging Western Buddhism - Gurus, Sandra Bell (2002), Durham University

- The Guru as Pastoral Counselor, Raymond Williams (1986), Journal of Pastoral Care Counseling

- The Tradition of Female Gurus Archived 2016-04-07 at the Wayback Machine, Catherine Clémentin-Ojha (1985)

- The Guru in Hindu Tradition, J Mlecko (1982), Numen journal

Etymology and Definition

Linguistic Origins

The term "guru" originates from Sanskrit, where it is derived from the roots "gu," signifying darkness or ignorance, and "ru," denoting the remover or dispeller, thus connoting one who eliminates ignorance.[8] This etymological interpretation, while rooted in traditional explanations, reflects the word's evolution from a descriptor of weighty importance to a revered guide. The actual linguistic root traces to "gṛ" or "gur," meaning heavy or weighty, implying something or someone of substantial significance, as documented in classical Sanskrit lexicons.[9] The word first appears in ancient Vedic texts, composed around 1500 BCE, marking its early attestation in Indo-Aryan literature. Earliest textual evidence of "guru" is found in the Rigveda, the oldest Vedic hymn collection, where it denotes a heavy or burdensome entity, as in hymn 4.5.6, and evolves to signify a teacher or preceptor by the time of the Upanishads (circa 800–500 BCE), later Vedic layers emphasizing instructional roles.[10] In these contexts, "guru" refers to a venerable figure imparting knowledge, distinct from mere pedagogy, underscoring its foundational role in Sanskrit's semantic field for authority and wisdom. The term spread from Sanskrit to other Indian languages as a loanword, retaining its core meaning with minor phonetic adaptations. In Hindi and Punjabi, it remains "guru," directly borrowed for teacher or spiritual guide, while in Tamil, it appears as "kuru" or "guru," integrated into Dravidian contexts via cultural exchange.[11] This dissemination occurred through the pervasive influence of Sanskrit on Indo-Aryan languages like Hindi and Punjabi, and on Dravidian ones like Tamil, facilitated by religious and literary transmissions over millennia. In English, "guru" entered via British colonial transliterations in the 17th–19th centuries, initially denoting Indian spiritual teachers before broadening to expert connotations. Beyond the subcontinent, "guru" influenced Persian during the Mughal era (16th–19th centuries), where it was transliterated as "goru" to denote an elder or master, adapting to avoid mispronunciation as "garī." This variant appears in Persian chronicles documenting interactions with Indian traditions, highlighting cross-cultural linguistic borrowing under Mughal rule.Symbolic Meanings

The term "guru" embodies deep symbolic significance in Indian philosophical traditions, foremost as the dispeller of darkness, metaphorically representing the enlightenment that eradicates ignorance, or avidya, and leads to profound self-awareness.[12][13] This core symbolism underscores the guru's function in transforming the seeker's inner world from obscurity to clarity, much like a beacon guiding through existential shadows.[14] In Vedantic philosophy, the guru is intrinsically linked to jyoti, the eternal light of divine consciousness, symbolizing the embodiment of supreme wisdom that reveals the unity of the self with the ultimate reality.[15] This association portrays the guru not merely as a teacher but as the radiant source of vidya (knowledge), illuminating the subtle veils of illusion (maya) that obscure true perception.[16] Extending beyond literal guidance, the guru serves as a metaphorical bridge spanning the human and divine realms in broader Indian thought, enabling the transcendence of worldly limitations toward spiritual union and inner divinity.[17] This bridge-like role highlights the guru's capacity to harmonize the mundane with the transcendent, fostering a pathway for devotees to access higher states of being.[18] Cultural icons further enrich this symbolism, such as the guru's staff (danda), which denotes spiritual authority, discipline, and the unyielding power of awakened consciousness to uphold dharma.[19] Complementing it, the guru's seat (asana) signifies purity, stability, and elevated moral stature, serving as a sacred emblem of grounded enlightenment and the foundation for profound contemplation.[20]The Guru in Hinduism

Scriptural Foundations

The Upanishads, as the concluding philosophical portions of the Vedic corpus, establish the guru as an indispensable guide for attaining higher knowledge and spiritual realization. A pivotal reference appears in the Mundaka Upanishad (1.2.12), where it is advised: "Let a Brahmana, after he has examined all these worlds that are gained by works, take refuge in a preceptor who is well-versed in the Vedas and is established in Brahman, in order to obtain the knowledge of the Imperishable." This verse highlights the guru's role as a beacon of eternal truth, surpassing ritualistic actions and emphasizing direct transmission of wisdom to dispel ignorance. The Bhagavad Gita further solidifies the guru's scriptural prominence, portraying them as the repository of sacred knowledge essential for self-realization. In Chapter 4, Verse 34, Krishna counsels Arjuna: "Tad viddhi praṇipātena paripraśnena sevayā / Upadekṣyanti te jñānaṁ jñāninas tattvadarśinaḥ," translating to "Learn that by humble submission, by inquiry, and by service; the wise ones who have realized the Truth will impart the knowledge to you." Here, the guru is depicted as a seer of ultimate reality (tattva-darśin), whose guidance through devotion and questioning leads the disciple beyond mere scriptural study to experiential insight. Mentions in the Puranas and Dharma Shastras elevate the guru to a divine equivalence, reinforcing their foundational status in Hindu thought. The Guru Gita, a dialogue between Shiva and Parvati within the Skanda Purana, asserts in Verse 33: "Gurur brahmā gurur viṣṇuḥ gurur devo maheśvaraḥ / Guruḥ sākṣāt paraṁ brahma tasmai śrī-gurave namaḥ," meaning "The Guru is Brahma, the Guru is Vishnu, the Guru is the great God Maheśvara; the Guru is verily the Parabrahman manifest; salutations to that revered Guru." This equates the guru with the Trimurti and ultimate reality, portraying them as the direct embodiment of divinity. Similarly, the Dharma Shastras, such as the Manusmriti (2.225), describe the guru as "superior to a thousand fathers and mothers" in conferring spiritual merit, underscoring their unparalleled reverence. This scriptural portrayal reflects an evolution from the Vedic rishis—seers who intuitively perceived cosmic truths (ṛṣi, from √dṛś "to see")—to the classical guru in post-Vedic texts, where the emphasis shifts to personalized instruction and ethical guidance. In the Vedic period, rishis like those in the Rigveda transmitted knowledge orally within ritual contexts, but by the time of the Manusmriti (circa 200 BCE–200 CE), the guru emerges as a formalized mentor in domestic and soteriological roles, bridging divine insight with human discipleship.[21]Role in Spiritual Guidance

In Hinduism, the guru serves as the essential guide on the spiritual path, with primary duties encompassing the transmission of knowledge (jnana), the cultivation of ethical conduct (dharma), and the instruction in meditation techniques to facilitate inner transformation. Through personal instruction, the guru imparts scriptural wisdom and practical insights, helping the disciple discern the illusory nature of the material world and realize the self (atman). This role is exemplified in the Bhagavad Gita, where Lord Krishna, as the archetypal guru, advises Arjuna to approach a realized teacher for enlightenment, emphasizing that true knowledge arises from humble inquiry and service to the guru.[22] A key method in the guru's guidance is diksha, the formal initiation that awakens the disciple's spiritual potential and establishes a sacred bond, often involving the bestowal of a mantra or ritual to purify the mind and begin the journey toward liberation (moksha). The guru assesses the disciple's readiness through testing their commitment and moral foundation, ensuring they are prepared for deeper practices; only then does instruction progress from foundational ethical teachings—such as truthfulness, non-violence, and righteous action as outlined in the Taittiriya Upanishad—to advanced disciplines.[23] In this text, the guru exhorts the disciple to "speak the truth, practice dharma, and devote oneself to Vedic study," laying the groundwork for ethical living as a prerequisite for higher realization.[24] The stages of guidance under the guru typically advance from basic moral education, where the focus is on instilling virtues and self-discipline, to intermediate contemplative practices like reflection (manana) on scriptural truths, and culminate in profound meditative absorption (nididhyasana) or tantric/yogic techniques that dissolve egoic identifications. This progressive approach enables the disciple to transcend personal limitations, with the guru's vigilant oversight preventing deviations and accelerating progress toward moksha by revealing the unity of the individual soul with the ultimate reality (Brahman). In Vedantic traditions, the guru's intervention is crucial for overcoming the ego (ahamkara), as self-effort alone cannot eradicate deep-seated ignorance (avidya), a principle reinforced in texts like the Chandogya Upanishad where divine grace through the guru illuminates the path to freedom.[6]Guru-Shishya Tradition

The Guru-Shishya tradition in Hinduism centers on the gurukula system, an ancient residential educational framework where the shishya, or disciple, resided in the guru's household, often in a forest ashram, and rendered personal service to the teacher in exchange for holistic knowledge encompassing the Vedas, arts, sciences, and moral values.[25] This immersive model, rooted in Vedic texts, emphasized direct transmission of wisdom through oral instruction and practical apprenticeship, fostering not only intellectual growth but also character development through daily chores and ethical discipline.[26] Prevalent from the Vedic period through the medieval era, the gurukula thrived as the primary mode of education until the 19th century, with disciples typically entering between ages 8 and 12 and remaining for 12 years or more.[27] Entry into this tradition began with initiation rites known as diksha, a sacred ceremony marking the shishya's formal acceptance under the guru, often involving rituals such as purification, oaths of celibacy during study, and a symbolic transfer of knowledge through mantras or touch.[28] The shishya pledged vows of absolute obedience, humility, and devotion, viewing the guru as a divine embodiment of knowledge, which cultivated a profound, hierarchical bond of trust and mutual respect.[29] This relationship extended lifelong, even after the disciple's departure from the gurukula, obligating ongoing reverence, service, and the propagation of the guru's lineage through parampara, ensuring the continuity of sacred teachings.[28] Historical exemplars illustrate the tradition's depth, such as the bond between Chanakya (also known as Kautilya) and Chandragupta Maurya in the 4th century BCE, where the scholar-mentor trained the young prince in statecraft, strategy, and governance, enabling the founding of the Maurya Empire.[30] Similarly, in the epic Mahabharata, Dronacharya served as the royal preceptor to the Pandavas and Kauravas, imparting martial arts and archery, with Arjuna exemplifying the ideal shishya through unwavering dedication and skill mastery under rigorous tutelage.[31] The gurukula system's decline accelerated in the 19th century under British colonial rule, particularly following the 1835 Macaulay Minute and subsequent policies that prioritized English-medium Western education, marginalizing indigenous institutions and reducing their patronage.[27] Revival efforts emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries through reformers like Swami Dayananda Saraswati, founder of the Arya Samaj in 1875, who reestablished gurukuls in ashrams to blend Vedic learning with modern subjects, followed by initiatives from Swami Shraddhanand that expanded such centers across India.[32]Reverence and Attributes

In Hinduism, the guru is venerated through guru-bhakti, a form of devotional worship that elevates the guru to the status of a divine incarnation, embodying the supreme reality and serving as a conduit for spiritual enlightenment. This reverence underscores the guru's role in dispelling ignorance, with disciples offering complete surrender and adoration akin to that reserved for deities. A prominent expression of this devotion is the Guru Purnima festival, observed on the full moon day of the Hindu month of Ashadha (typically July), where followers honor their gurus through prayers, rituals, and reflections on their teachings, commemorating the transmission of wisdom from Lord Shiva as the Adi Guru to the seven sages.[33][34] The ideal attributes of a true guru are detailed in sacred texts such as the Guru Gita, a dialogue between Lord Shiva and Parvati within the Skanda Purana, emphasizing qualities that ensure spiritual authenticity and efficacy. These include shuddhi (purity of body, mind, and actions), jnana (profound wisdom and realization of ultimate truth), karuna (compassion toward all beings), and vairagya (detachment from worldly attachments and ego). A guru embodying these traits guides disciples selflessly, fostering inner transformation without personal gain, and is recognized by their equanimity, ethical conduct, and alignment with scriptural principles.[35][36] Hindu scriptures issue strong warnings against false gurus, particularly in the Kali Yuga, an era characterized by moral decline where impostors exploit devotees for material or egoistic ends, as prophesied in texts like the Bhagavata Purana and Shiva Purana. Signs of an authentic guru include unwavering adherence to dharma, humility, and the ability to inspire genuine spiritual progress without demanding undue allegiance or wealth; conversely, those who contradict shastra, promote self-glorification, or engage in hypocrisy are deemed fraudulent.[37][38] Central to this veneration are rituals like guru puja, a ceremonial worship involving offerings of flowers, incense, and food to the guru's feet or image, symbolizing humility and receptivity to divine grace. A key practice is the washing of the guru's feet with sacred water, collected as charanamrita for disciples to partake in, signifying purification and blessings. This is often accompanied by the chanting of the revered mantra: Guru Brahma Guru Vishnu Guru Devo Maheshwara, Guru Sakshat Para Brahma Tasmai Shri Guruve Namah, which equates the guru with the Trimurti—Brahma the creator, Vishnu the preserver, Shiva the destroyer—and the ultimate Brahman, affirming the guru's transcendent essence.[39][40]Modern Developments