Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

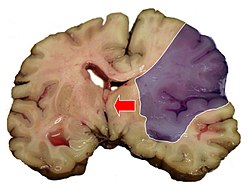

Midline shift

View on Wikipedia

Midline shift is a shift of the brain past its center line.[1] The sign may be evident on neuroimaging such as CT scanning.[1] The sign is considered ominous because it is commonly associated with a distortion of the brain stem that can cause serious dysfunction evidenced by abnormal posturing and failure of the pupils to constrict in response to light.[1] Midline shift is often associated with high intracranial pressure (ICP), which can be deadly.[1] In fact, midline shift is a measure of ICP; presence of the former is an indication of the latter.[2] Presence of midline shift is an indication for neurosurgeons to take measures to monitor and control ICP.[1] Immediate surgery may be indicated when there is a midline shift of over 5 mm.[3][4] The sign can be caused by conditions including traumatic brain injury,[1] stroke, hematoma, or birth deformity that leads to a raised intracranial pressure.

Methods of detection

[edit]

Doctors detect midline shift using a variety of methods. The most prominent measurement is done by a computed tomography (CT) scan and the CT Gold Standard is the standardized operating procedure for detecting MLS.[5] Since the midline shift is often easily visible with a CT scan, the high precision of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is not necessary, but can be used with equally adequate results.[5] Newer methods such as bedside sonography can be used with neurocritical patients who cannot undergo some scans due to their dependence on ventilators or other care apparatuses.[6] Sonography has proven satisfactory in the measurement of MLS, but is not expected to replace CT or MRI.[6] Automated measurement algorithms are used for exact recognition and precision in measurements from an initial CT scan.[7] A major benefit to using the automated recognition tools includes being able to measure even the most deformed brains because the method doesn’t depend on normal brain symmetry.[7] Also, it lessens the chance of human error by detecting MLS from an entire image set compared to selecting the single most important slice, which allows the computer to do the work that was once manually done.[7]

Structures of the midline

[edit]Three main structures are commonly investigated when measuring midline shift. The most important of these is the septum pellucidum, which is a thin and linear layer of tissue located between the right and left ventricles.[7] It is easily found on CT or MRI images due to its unique hypodensity.[7] The other two important structures of the midline include the third ventricle and the pineal gland, which are both centrally located and caudal to the septum pellucidum.[6][7] Identifying the location of these structures on a damaged brain compared to an unaffected brain is another way of categorizing the severity of the midline shift. The terms mild, moderate, and severe are associated with the extent of increasing damage.

Midline shift in diagnoses

[edit]Midline shift measurements and imaging has multiple applications. The severity of brain damage is determined by the magnitude of the change in symmetry. Another use is secondary screening to determine deviations in brain trauma at different times after a traumatic injury as well as initial shifts immediately after.[3] The severity of shift is directly proportional to the likeliness of surgery having to be performed. The degree of MLS can also be used to diagnose the pathology that caused it. The MLS measurement can be used to successfully distinguish between a variety of intracranial conditions including acute subdural hematoma,[5][7] malignant middle cerebral artery infarction,[3] epidural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, chronic subdural hematoma, infarction, intraventrical hemorrhage, a combination of these symptoms, or the absence of pertinent damage altogether.[7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Gruen P (May 2002). "Surgical management of head trauma". Neuroimaging Clinics of North America. 12 (2): 339–43. doi:10.1016/S1052-5149(02)00013-8. PMID 12391640.

- ^ Maas AI, Stocchetti N, Bullock R (August 2008). "Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in adults". Lancet Neurology. 7 (8): 728–41. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70164-9. PMID 18635021. S2CID 14071224.

- ^ a b c Po-Hsun Tu; Zhuo-Hao Liu; Chi-Cheng Chuang; Tao-Chieh Yang; Chieh-Tsai Wu; Shih-Tseng Lee (May 2012). "Postoperative midline shift as secondary screening for the long-term outcomes of surgical decompression of malignant middle cerebral artery infarcts". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 19 (5): 661–664. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2011.07.045. PMID 22377637. S2CID 22895391.

- ^ Valadka AB (2004). "Injury to the cranium". In Moore EJ, Feliciano DV, Mattox KL (eds.). Trauma. New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division. p. 389. ISBN 0-07-137069-2. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- ^ a b c Kim, Jane J.; Alisa D. Gean (January 2011). "Imaging for the diagnosis and management of traumatic brain injury". Neurotherapeutics. 8 (1): 39–53. doi:10.1007/s13311-010-0003-3. PMC 3026928. PMID 21274684.

- ^ a b c Motuel, J; Biette; Congard; Fourcade; Geeraerts (2011). "Brain midline shift assessment using bedside sonography in neurocritical care patients". Critical Care. 15 (1): 343. doi:10.1186/cc9763. PMC 3067017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Xiao, Furen; Chiang; Wong; Tsai; Huang; Liao (2011). "Automatic measurement of midline shift on deformed brains using multiresolution binary level set method and Hough transform". Computers in Biology and Medicine. 41 (9): 756–762. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2011.06.011. PMID 21722887.