Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

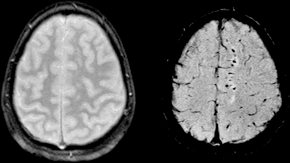

Diffuse axonal injury

View on Wikipedia| Diffuse axonal injury | |

|---|---|

| |

| Two MRI images of a patient with diffuse axonal injury resulting from trauma, at 1.5 tesla field strength. Left: conventional gradient recalled echo (GRE). Right: Susceptibility weighted image (SWI). | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Diffuse axonal injury (DAI) is a brain injury in which scattered lesions occur over a widespread area in white matter tracts as well as grey matter.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] DAI is one of the most common and devastating types of traumatic brain injury[8] and is a major cause of unconsciousness and persistent vegetative state after severe head trauma.[9] It occurs in about half of all cases of severe head trauma and may be the primary damage that occurs in concussion. The outcome is frequently coma, with over 90% of patients with severe DAI never regaining consciousness.[9] Those who awaken from the coma often remain significantly impaired.[10]

DAI can occur across the spectrum of traumatic brain injury (TBI) severity, wherein the burden of injury increases from mild to severe.[11][12] Concussion may be a milder type of diffuse axonal injury.[12][13]

Mechanism

[edit]DAI is the result of traumatic shearing forces that occur when the head is rapidly accelerated or decelerated, as may occur in car accidents, falls, and assaults.[14] Vehicle accidents are the most frequent cause of DAI; it can also occur as the result of child abuse[15] such as in shaken baby syndrome.[16]

Immediate disconnection of axons may be observed in severe brain injury, but the major damage of DAI is delayed secondary axon disconnections, slowly developed over an extended time course.[2] Tracts of axons, which appear white due to myelination, are referred to as white matter. Lesions in both grey and white matter are found in postmortem brains in CT and MRI exams.[9]

Besides mechanical breakage of the axonal cytoskeleton, DAI pathology also includes secondary physiological changes, such as interrupted axonal transport, progressive swellings known as axonal varicosities, and degeneration.[17] Recent studies have linked these changes to twisting and misalignment of broken axon microtubules, as well as tau protein and amyloid precursor protein (APP) deposition.[17][18]

Characteristics

[edit]Lesions typically are found in the white matter of brains injured by DAI; these lesions vary in size from about 1–15 mm and are distributed in a characteristic pattern.[9] DAI most commonly affects white matter in areas including the brain stem, the corpus callosum, and the cerebral hemispheres.

The lobes of the brain most likely to be injured are the frontal and temporal lobes.[19] Other common locations for DAI include the white matter in the cerebral cortex, the superior cerebral peduncles,[16] basal ganglia, thalamus, and deep hemispheric nuclei.[clarification needed][20] These areas may be more easily damaged because of the difference in density between them and the other regions of the brain.[20]

Histological characteristics

[edit]DAI is characterized by axonal separation, in which the axon is torn at the site of stretch and the part distal to the tear degrades by a process known as Wallerian degeneration. While it was once thought that the main cause of axonal separation was tearing due to mechanical forces during the trauma event, it is now understood that axons are not typically torn upon impact; rather, secondary biochemical cascades, which occur in response to the primary injury (which occurs as the result of mechanical forces at the moment of trauma) and take place hours to days after the initial injury, are largely responsible for the damage to axons.[21][22][23]

Though the processes involved in secondary brain injury are still poorly understood, it is now accepted that stretching of axons during injury causes physical disruption to and proteolytic degradation of the cytoskeleton.[24] It also opens sodium channels in the axolemma, which causes voltage-gated calcium channels to open and Ca2+ to flow into the cell.[24] The intracellular presence of Ca2+ triggers several different pathways, including activating phospholipases and proteolytic enzymes damaging mitochondria and the cytoskeleton, and activating secondary messengers, which can lead to separation of the axon and death of the cell.[21]

Cytoskeleton disruption

[edit]

Axons are normally elastic, but when rapidly stretched they become brittle, and the axonal cytoskeleton can be broken. Misalignment of cytoskeletal elements after stretch injury can lead to tearing of the axon and death of the neuron. Axonal transport continues up to the point of the break in the cytoskeleton, but no further, leading to a buildup of transport products and local swelling at that point.[25] When this swelling becomes large enough, it can tear the axon at the site of the cytoskeleton break, causing it to draw back toward the cell body and form a bulb.[11] This bulb is called a "retraction ball", the histological hallmark of diffuse axonal injury.[9]

When the axon is torn, Wallerian degeneration, in which the part of the axon distal to the break degrades, takes place within one to two days after injury.[26] The axolemma disintegrates,[26] myelin breaks down and begins to detach from the cell in an anterograde direction (from the body of the cell toward the end of the axon),[27] and nearby cells begin phagocytic activity, engulfing the cellular debris.[28]

Calcium influx

[edit]While sometimes only the cytoskeleton is disturbed, frequently disruption of the axolemma occurs as well, causing the influx of Ca2+ ions into the cell and unleashing a variety of degradational processes.[26][29] An increase in Ca2+ and Na+ levels and a drop in K+ levels are found within the axon immediately after injury.[21][26] Possible routes of Ca2+ entry include sodium channels, pores formed in the membrane during stretch, and failure of ATP-dependent transporters due to mechanical blockage or lack of available metabolic energy.[21] High levels of intracellular Ca2+, the major cause of post-injury cell damage,[30] destroy mitochondria,[11] and trigger phospholipases and proteolytic enzymes that damage Na+ channels and degrade or alter the cytoskeleton and the axoplasm.[31][26] Excess Ca2+ can also lead to damage to the blood–brain barrier and swelling of the brain.[30]

One of the proteins activated by the presence of calcium in the cell is calpain, a Ca2+-dependent non-lysosomal protease.[31] About 15 minutes to half an hour after the onset of injury, a process called calpain-mediated spectrin proteolysis, or CMSP, begins to occur.[32] Calpain breaks down a molecule called spectrin, which holds the membrane onto the cytoskeleton, causing the formation of blebs and the breakdown of the cytoskeleton and the membrane, and ultimately the death of the cell.[31][32] Other molecules that can be degraded by calpains are microtubule subunits, microtubule-associated proteins, and neurofilaments.[31]

Generally occurring one to six hours into the process of post-stretch injury, the presence of calcium in the cell initiates the caspase cascade, a process in cell injury that usually leads to apoptosis, or "programmed cell death".[32]

Mitochondria, dendrites, and parts of the cytoskeleton damaged in the injury have a limited ability to heal and regenerate, a process which occurs over two or more weeks.[33] After the injury, astrocytes can shrink, causing parts of the brain to atrophy.[9]

Diagnosis

[edit]

DAI is difficult to detect since it does not show up well on CT scans or with other macroscopic imaging techniques, though it shows up microscopically.[9] However, there are characteristics typical of DAI that may or may not show up on a CT scan. Diffuse injury has more microscopic injury than macroscopic injury and is difficult to detect with CT and MRI, but its presence can be inferred when small bleeds are visible in the corpus callosum or the cerebral cortex.[34] MRI is more useful than CT for detecting characteristics of diffuse axonal injury in the subacute and chronic time frames.[35] Newer studies such as Diffusion Tensor Imaging are able to demonstrate the degree of white matter fiber tract injury even when the standard MRI is negative. Since axonal damage in DAI is largely a result of secondary biochemical cascades, it has a delayed onset, so a person with DAI who initially appears well may deteriorate later. Thus injury is frequently more severe than is realized, and medical professionals should suspect DAI in any patients whose CT scans appear normal but who have symptoms like unconsciousness.[9]

MRI is more sensitive than CT scans, but is still liable to false negatives because DAI is identified by looking for signs of edema, which may not always be present.[33]

DAI is classified into grades based on severity of the injury. In Grade I, widespread axonal damage is present but no focal abnormalities are seen. In Grade II, damage found in Grade I is present in addition to focal abnormalities, especially in the corpus callosum. Grade III damage encompasses both Grades I and II plus rostral brain stem injury and often tears in the tissue.[36]

Treatment

[edit]DAI currently lacks specific treatment beyond that for any type of head injury, which includes stabilizing the patient and trying to limit increases in intracranial pressure (ICP).[citation needed]

History

[edit]The idea of DAI first came about as a result of studies by Sabina Strich on lesions of the white matter of individuals who had sustained head trauma years before.[37] Strich first proposed the idea in 1956, calling it diffuse degeneration of white matter; however, the more concise term "diffuse axonal injury" came to be preferred.[38] Strich was researching the relationship between dementia and head trauma[37] and asserted in 1956 that DAI played an integral role in the eventual development of dementia due to head trauma.[15] The term DAI was introduced in the early 1980s.[39]

Notable examples

[edit]- Top Gear presenter Richard Hammond sustained a DAI as a result of the Vampire dragster crash in 2006.[40]

- Champ Car World Series driver Roberto Guerrero suffered a DAI as a result of a crash during testing at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 1987.[41]

- Formula 1 driver Jules Bianchi suffered a DAI as a result of an accident at the 2014 Japanese Grand Prix[42] and died without regaining consciousness 9 months later.[43]

- Actor and audiobook narrator Frank Muller, who read Stephen King's The Dark Tower, suffered a DAI in 2001 due to a motorcycle accident. He died in 2008.[44]

- NASCAR driver Adam Petty, grandson of seven time Cup Series champion Richard Petty, sustained a diffuse axonal injury secondary to a fatal basilar skull fracture in May 2000 at New Hampshire Motor Speedway during practice for the upcoming race.[45]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Strich SJ (August 1956). "Diffuse degeneration of the cerebral white matter in severe dementia following head injury". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 19 (3): 163–85. doi:10.1136/jnnp.19.3.163. PMC 497203. PMID 13357957.

- ^ a b Povlishock JT, Becker DP, Cheng CL, Vaughan GW (May 1983). "Axonal change in minor head injury". Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 42 (3): 225–42. doi:10.1097/00005072-198305000-00002. PMID 6188807. S2CID 24260379.

- ^ Adams JH (March 1982). "Diffuse axonal injury in non-missile head injury". Injury. 13 (5): 444–5. doi:10.1016/0020-1383(82)90105-X. PMID 7085064.

- ^ Christman CW, Grady MS, Walker SA, Holloway KL, Povlishock JT (April 1994). "Ultrastructural studies of diffuse axonal injury in humans". Journal of Neurotrauma. 11 (2): 173–86. doi:10.1089/neu.1994.11.173. PMID 7523685.

- ^ Povlishock JT, Christman CW (August 1995). "The pathobiology of traumatically induced axonal injury in animals and humans: a review of current thoughts". Journal of Neurotrauma. 12 (4): 555–64. doi:10.1089/neu.1995.12.555. PMID 8683606.

- ^ Vascak M, Jin X, Jacobs KM, Povlishock JT (May 2018). "Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Induces Structural and Functional Disconnection of Local Neocortical Inhibitory Networks via Parvalbumin Interneuron Diffuse Axonal Injury". Cerebral Cortex. 28 (5): 1625–1644. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhx058. PMC 5907353. PMID 28334184.

- ^ Smith DH, Hicks R, Povlishock JT (March 2013). "Therapy development for diffuse axonal injury". Journal of Neurotrauma. 30 (5): 307–23. doi:10.1089/neu.2012.2825. PMC 3627407. PMID 23252624.

- ^ Povlishock JT, Katz DI (January 2005). "Update of neuropathology and neurological recovery after traumatic brain injury". The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 20 (1): 76–94. doi:10.1097/00001199-200501000-00008. PMID 15668572. S2CID 1094129.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wasserman J. and Koenigsberg R.A. (2007). Diffuse axonal injury. Emedicine.com. Retrieved on 2008-01-26.

- ^ Vinas F.C. and Pilitsis J. (2006). Penetrating head trauma. Emedicine.com. Retrieved on 2008-01-14.

- ^ a b c Smith DH, Meaney DF (December 2000). "Axonal damage in traumatic brain injury". The Neuroscientist. 6 (6): 483–95. doi:10.1177/107385840000600611. S2CID 86550146.

- ^ a b Blumbergs PC, Scott G, Manavis J, Wainwright H, Simpson DA, McLean AJ (August 1995). "Topography of axonal injury as defined by amyloid precursor protein and the sector scoring method in mild and severe closed head injury". Journal of Neurotrauma. 12 (4): 565–72. doi:10.1089/neu.1995.12.565. PMID 8683607.

- ^ Bazarian JJ, Blyth B, Cimpello L (February 2006). "Bench to bedside: evidence for brain injury after concussion--looking beyond the computed tomography scan". Academic Emergency Medicine. 13 (2): 199–214. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2005.07.031. PMID 16436787.

- ^ Gennarelli TA (1993). "Mechanisms of brain injury". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 11 (Suppl 1): 5–11. PMID 8445204.

- ^ a b Hardman JM, Manoukian A (May 2002). "Pathology of head trauma". Neuroimaging Clinics of North America. 12 (2): 175–87, vii. doi:10.1016/S1052-5149(02)00009-6. PMID 12391630.

- ^ a b Smith D. and Greenwald B. 2003.Management and staging of traumatic brain injury. Emedicine.com. Retrieved through web archive on 17 January 2008.

- ^ a b Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH (August 2013). "Axonal pathology in traumatic brain injury". Experimental Neurology. Special Issue: Axonal degeneration. 246: 35–43. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.01.013. PMC 3979341. PMID 22285252.

- ^ Tang-Schomer MD, Patel AR, Baas PW, Smith DH (May 2010). "Mechanical breaking of microtubules in axons during dynamic stretch injury underlies delayed elasticity, microtubule disassembly, and axon degeneration". FASEB Journal. 24 (5): 1401–10. doi:10.1096/fj.09-142844. PMC 2879950. PMID 20019243.

- ^ Boon R, de Montfor GJ (2002). "Brain injury". Learning Discoveries Psychological Services. Archived from the original on 2006-09-03. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- ^ a b Singh J, Stock A (September 25, 2006). "Head Trauma". Emedicine.com. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ a b c d Wolf JA, Stys PK, Lusardi T, Meaney D, Smith DH (2001). "Traumatic axonal injury induces calcium influx modulated by tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium channels". Journal of Neuroscience. 21 (6): 1923–1930. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01923.2001. PMC 6762603. PMID 11245677.

- ^ Arundine M, Aarts M, Lau A, Tymianski M (September 2004). "Vulnerability of central neurons to secondary insults after in vitro mechanical stretch". Journal of Neuroscience. 24 (37): 8106–23. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1362-04.2004. PMC 6729801. PMID 15371512.

- ^ a b Mouzon B, Chaytow H, Crynen G, Bachmeier C, Stewart J, Mullan M, Stewart W, Crawford F (December 2012). "Repetitive mild traumatic brain injury in a mouse model produces learning and memory deficits accompanied by histological changes" (PDF). Journal of Neurotrauma. 29 (18): 2761–2173. doi:10.1089/neu.2012.2498. PMID 22900595.

- ^ a b Iwata A, Stys PK, Wolf JA, Chen XH, Taylor AG, Meaney DF, Smith DH (2004). "Traumatic axonal injury induces proteolytic cleavage of the voltage-gated sodium channels modulated by tetrodotoxin and protease inhibitors". The Journal of Neuroscience. 24 (19): 4605–4613. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0515-03.2004. PMC 6729402. PMID 15140932.

- ^ Staal JA, Dickson TC, Chung RS, Vickers JC (2007). "Cyclosporin-A treatment attenuates delayed cytoskeletal alterations and secondary axotomy following mild axonal stretch injury". Developmental Neurobiology. 67 (14): 1831–1842. doi:10.1002/dneu.20552. PMID 17702000. S2CID 19415197.

- ^ a b c d e LoPachin RM, Lehning EJ (1997). "Mechanism of calcium entry during axon injury and degeneration". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 143 (2): 233–244. Bibcode:1997ToxAP.143..233L. doi:10.1006/taap.1997.8106. PMID 9144441.

- ^ Cowie RJ, Stanton GB (2005). "Axoplasmic transport and neuronal responses to injury". Howard University College of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2005-10-29. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ Hughes PM, Wells GM, Perry VH, Brown MC, Miller KM (2002). "Comparison of matrix metalloproteinase expression during wallerian degeneration in the central and peripheral nervous systems". Neuroscience. 113 (2): 273–287. doi:10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00183-5. PMID 12127085. S2CID 37213275.

- ^ Povlishock JT, Pettus EH (1996). "Traumatically Induced Axonal Damage: Evidence for Enduring Changes in Axolemmal Permeability with Associated Cytoskeletal Change". Mechanisms of Secondary Brain Damage in Cerebral Ischemia and Trauma. Vol. 66. pp. 81–86. doi:10.1007/978-3-7091-9465-2_15. ISBN 978-3-7091-9467-6. PMID 8780803.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b Zhou F, Xiang Z, Feng WX, Zhen LX (2001). "Neuronal free Ca2+ and BBB permeability and ultrastructure in head injury with secondary insult". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 8 (6): 561–563. doi:10.1054/jocn.2001.0980. PMID 11683606. S2CID 43789581.

- ^ a b c d Castillo MR, Babson JR (1998). "Ca2+-dependent mechanisms of cell injury in cultured cortical neurons". Neuroscience. 86 (4): 1133–1144. doi:10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00070-0. PMID 9697120. S2CID 54228571.

- ^ a b c Büki A, Okonkwo DO, Wang KK, Povlishock JT (April 2000). "Cytochrome c release and caspase activation in traumatic axonal injury". primary. The Journal of Neuroscience. 20 (8): 2825–34. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02825.2000. PMC 6772193. PMID 10751434.

- ^ a b Corbo J, Tripathi P (2004). "Delayed presentation of diffuse axonal injury: A case report". Trauma. 44 (1): 57–60. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.11.010. PMID 15226709.

- ^ Crooks CY, Zumsteg JM, Bell KR (November 2007). "Traumatic brain injury: a review of practice management and recent advances". Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America. 18 (4): 681–710, vi. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2007.06.005. PMID 17967360.

- ^ Maas AI, Stocchetti N, Bullock R (August 2008). "Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in adults". The Lancet. Neurology. 7 (8): 728–41. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70164-9. PMID 18635021. S2CID 14071224.

- ^ Lees-Haley PR, Green P, Rohling ML, Fox DD, Allen LM (August 2003). "The lesion(s) in traumatic brain injury: implications for clinical neuropsychology". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 18 (6): 585–94. doi:10.1016/S0887-6177(02)00155-5. PMID 14591433.

- ^ a b Pearce JM (2007). "Observations on concussion. A review". European Neurology. 59 (3–4): 113–9. doi:10.1159/000111872. PMID 18057896. S2CID 10245120.

- ^ Gennarelli GA, Graham DI (2005). "Neuropathology". In Silver JM, McAllister TW, Yudofsky SC (eds.). Textbook Of Traumatic Brain Injury. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-58562-105-7. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- ^ Granacher RP (2007). Traumatic Brain Injury: Methods for Clinical & Forensic Neuropsychiatric Assessment, Second Edition. Boca Raton: CRC. pp. 26–32. ISBN 978-0-8493-8138-6. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

- ^ "Hammond's next six months unclear". September 29, 2006 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "The story of Roberto Guerrero and why to keep every faith in Bianchi's recovery". October 8, 2014.

- ^ "Jules Bianchi: Family confirms Formula One driver sustained traumatic brain injury in Japanese GP crash". Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ^ "F1 driver Jules Bianchi dies from crash injuries". BBC Sport. BBC. 2015-07-18. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ "Frank Muller, The Fight of his Life". 2006. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- ^ Macur, Juliet (September 16, 2000). "NASCAR's Limited Search For Answers". Washington Post.

External links

[edit]- Diffuse Axonal Injury MRI and CT Images

Diffuse axonal injury

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and types

Diffuse axonal injury (DAI) is a severe form of traumatic brain injury (TBI) characterized by widespread damage to the axons within the brain's white matter, resulting from shearing forces caused by rapid acceleration or deceleration of the head. This injury leads to scattered microscopic lesions in both white and gray matter across multiple brain regions, disrupting neural connectivity without a primary focal impact site.[8][9] Unlike focal traumatic brain injuries such as contusions or intracerebral hemorrhages, which involve localized bleeding or tissue destruction, DAI is inherently diffuse, affecting axons in the cerebral hemispheres, corpus callosum, brainstem, and sometimes cerebellum, often leading to immediate unconsciousness or prolonged coma.[8] As a subset of TBI, DAI commonly occurs in high-speed motor vehicle accidents or falls, emphasizing its association with diffuse rather than concentrated brain trauma.[10] DAI is classified into three grades based on the Adams grading system, which assesses the anatomical extent of axonal damage and correlates with clinical severity. Grade I involves histological evidence of axonal injury primarily in the white matter of the cerebral hemispheres, corpus callosum, and brainstem, typically without coma or with only brief loss of consciousness. Grade II includes the features of Grade I plus a focal lesion in the corpus callosum, associated with a decreased level of consciousness lasting more than 6 hours. Grade III encompasses Grades I and II with an additional focal lesion in the dorsolateral quadrant of the rostral brainstem, resulting in coma exceeding 24 hours and high mortality rates.[9][8][10]Epidemiology and risk factors

Diffuse axonal injury (DAI) is a major contributor to traumatic brain injury (TBI) morbidity and mortality worldwide, accounting for approximately 40-50% of severe TBI cases. Globally, over 50 million individuals sustain a TBI annually, with DAI elements present in a significant proportion, particularly in high-energy trauma scenarios. In the United States, recent estimates indicate approximately 2.5 million TBIs occur each year, with DAI accounting for 40-50% of severe cases.[1][11][1][12] Demographically, DAI predominantly affects young adults aged 15-24 and individuals over 65, reflecting peak TBI incidence patterns in these groups due to risk exposure. Males are affected at a higher rate than females, with a ratio of approximately 2:1, and up to 81% of severe DAI cases occurring in men, attributed to greater involvement in high-risk activities. Incidence is disproportionately elevated in low- and middle-income countries, where road traffic accidents drive a nearly threefold higher TBI burden compared to high-income settings.[1][1][13] Key risk factors for DAI include high-speed motor vehicle crashes, which account for 60-70% of cases, followed by falls, assaults, and sports-related injuries. Biomechanical forces such as rapid head rotation or deceleration during these events are critical precipitants. Comorbidities like alcohol use disorder and prior TBIs further increase susceptibility by impairing recovery and heightening vulnerability to subsequent injuries.[1][14][15] Mortality from DAI ranges from 20-30% in the acute phase, rising to up to 50% in severe cases, though pediatric patients exhibit lower rates (around 13%) compared to adults (18%). A 2025 meta-analysis of severe TBI with DAI reported a pooled mortality of 16% (95% CI: 0.07-0.30), reflecting improvements in trauma care and survival rates over recent decades, yet persistent high disability among survivors underscores the condition's impact.[1][16][17]Pathophysiology

Primary injury mechanisms

Diffuse axonal injury (DAI) primarily arises from biomechanical forces generated during rapid head acceleration and deceleration, particularly rotational movements that cause differential motion between the brain and skull. These forces induce shear, tensile, and compressive strains on neural tissues, leading to widespread axonal disruption without direct impact. In high-speed events such as motor vehicle crashes, rotational accelerations exceeding 10,000 rad/s² generate inertial loading that deforms the brain parenchyma, stretching axons beyond their elastic limits.[18] Seminal primate studies demonstrated that coronal plane accelerations produce DAI and coma, while sagittal accelerations result in milder concussion, highlighting the directional sensitivity of these injuries.[19] Long white matter tracts are particularly vulnerable due to their orientation and the brain's heterogeneous structure, with injury concentrating at gray-white matter junctions, the corpus callosum, brainstem, and subcortical regions. At these sites, axons experience peak strains of 20-50% during trauma, surpassing the tissue-level threshold of approximately 21% for morphological damage, often at strain rates greater than 100/s. Such high-rate stretching compromises axolemma integrity, increasing permeability and initiating immediate mechanical failure through cytoskeletal disruption.[20] [21] The initial cellular response involves rapid axonal retraction, forming characteristic retraction balls within 12-24 hours as neurofilaments accumulate distally. This process triggers the onset of Wallerian degeneration, where disconnected axonal segments undergo progressive breakdown. Strain threshold models qualitatively predict injury based on these mechanical parameters, emphasizing that exceeding elastic limits leads to irreversible disconnection rather than simple stretching.[22] [1] Disruption of ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) tracts in the brainstem contributes to immediate loss of consciousness, as these pathways are sheared during rotational trauma, impairing arousal mechanisms and resulting in coma.[19]Secondary injury processes

Following the primary mechanical damage to axons in diffuse axonal injury (DAI), secondary injury processes unfold over hours to days, involving biochemical cascades that exacerbate neuronal damage. A key initiator is the influx of calcium ions (Ca²⁺) through compromised axolemmal membranes, triggered by stretch-induced ion channel dysregulation. This uncontrolled Ca²⁺ entry leads to excitotoxicity, where excessive glutamate release further amplifies Ca²⁺ overload via NMDA receptor activation, creating a vicious cycle. Activated Ca²⁺-dependent enzymes, such as calpains and phospholipases, degrade cytoskeletal proteins, while mitochondrial calcium uptake impairs energy production and generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), promoting oxidative stress and cell death.[23][24] Cytoskeletal disruption constitutes a central feature of these secondary processes, as proteolytic cleavage by calpains targets neurofilaments and microtubules, leading to their disassembly and loss of structural integrity. This enzymatic degradation, compounded by caspase activation in apoptotic pathways, results in axonal beading and varicosities observable in animal models of DAI. Additionally, hyperphosphorylation of tau protein disrupts microtubule stability, further hindering intracellular scaffolding and contributing to the progressive axonal retraction seen in secondary axotomy. These changes impair the axon's ability to maintain its elongated morphology, setting the stage for irreversible degeneration.[25][26] The inflammatory response amplifies secondary injury through rapid microglial activation at sites of axonal damage, where resident immune cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). These mediators recruit peripheral leukocytes, exacerbate blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability via matrix metalloproteinase upregulation, and promote edema formation. Oligodendrocytes and neurons undergo apoptosis in response to this cytokine storm and ROS, leading to demyelination and white matter loss; studies in rodent models demonstrate that blocking IL-1β reduces apoptotic cell death and improves outcomes in DAI.[27] Axonal transport impairment emerges as a downstream consequence, with halted anterograde and retrograde trafficking due to microtubule depolymerization and motor protein dysfunction (e.g., kinesin and dynein). Accumulation of organelles and proteins proximal to injury sites causes axonal swelling, while distal segments undergo Wallerian-like degeneration over days to weeks. This transport failure, evidenced by reduced beta-amyloid precursor protein immunoreactivity in human DAI cases, perpetuates energy deficits and synaptic disconnection, contributing to long-term cognitive deficits.[26][28]Clinical presentation

Signs and symptoms

Diffuse axonal injury (DAI) typically presents with an immediate and profound alteration in consciousness following the traumatic event. The hallmark acute symptom is loss of consciousness or coma lasting at least 6 hours, often with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of less than 8, observed in approximately 70-72% of severe cases. This coma arises from widespread disruption of axonal connections in the cerebral white matter, leading to depressed arousal systems. Accompanying features may include post-traumatic amnesia, which commonly persists for days to weeks, reflecting impaired memory formation during the recovery phase. Additionally, transient autonomic instability, such as hypertension, and abnormal posturing like decerebrate rigidity can occur due to brainstem involvement in moderate to severe injuries. Upon partial recovery from coma, patients often exhibit a range of neurological deficits stemming from the diffuse nature of the axonal shearing. Motor impairments are frequent, including hemiparesis or unilateral weakness, ataxia affecting coordination, and spasticity from upper motor neuron damage. Sensory disturbances, such as loss of sensation in affected limbs, and cranial nerve palsies—potentially causing facial weakness or oculomotor dysfunction—may also manifest, depending on the regions of axonal damage. Cognitively, survivors frequently experience confusion, disorientation, and attentional deficits immediately upon regaining awareness, contributing to a confusional state that complicates initial assessment. In those who survive the acute phase, persistent symptoms can significantly impact quality of life and vary with injury severity. Common ongoing complaints include chronic headaches, dizziness, and profound fatigue, which may endure for months or longer as secondary effects of disrupted neural networks. These symptoms are more pronounced in higher-grade injuries; for instance, grade III DAI with brainstem lesions often results in severe motor restrictions, potentially resembling locked-in syndrome characterized by quadriplegia and preserved consciousness. The overall time course involves evolution from coma lasting hours to days, transitioning to focal deficits over weeks, with roughly 50% of patients demonstrating incomplete recovery and residual impairments at long-term follow-up.Grading and classification

Diffuse axonal injury (DAI) is graded primarily through pathological and imaging-based systems that categorize severity based on the extent and location of axonal damage, which informs prognosis and guides management. These classifications evolved from postmortem examinations to advanced in vivo techniques, facilitating earlier intervention in clinical settings.[1] The Adams grading system, introduced in 1989 but building on earlier pathological observations, divides DAI into three grades according to the anatomical distribution of microscopic axonal injury observed histologically. Grade I involves histological evidence of axonal damage in the white matter of the cerebral hemispheres, corpus callosum, brainstem, and cerebellum, typically associated with brief loss of consciousness. Grade II includes Grade I features plus a focal lesion in the corpus callosum, correlating with coma lasting more than 6 hours. Grade III encompasses Grade II plus focal lesions in the rostral brainstem, often linked to prolonged coma and higher mortality. In a series of 434 fatal non-missile head injuries, DAI was identified in 122 cases, with distributions of 10 Grade I, 29 Grade II, and 83 Grade III, highlighting the prevalence of severe forms.[1][29][9] The Gennarelli classification, developed in the early 1980s from primate models of head acceleration injury, laid the foundation for human DAI grading by emphasizing clinical and pathological features such as coma duration and axonal disruption severity. It similarly uses three grades, with Grade I showing mild, widespread axonal injury without focal lesions (0% mortality in model correlations), Grade II involving additional corpus callosum damage, and Grade III featuring brainstem involvement (up to 50% mortality). This system correlates injury grade with neurological outcomes, where higher grades predict increased dependence and death rates in translated human studies.[1][19][30] MRI-based grading extends traditional systems by visualizing lesions in vivo, often adapting the Adams framework to include lobar white matter, corpus callosum, and brainstem involvement, with added focus on hemorrhagic components for prognostic refinement. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), a key MRI modality, quantifies axonal integrity through metrics like fractional anisotropy, revealing subtle diffuse damage not apparent on conventional MRI and improving grade assignment for milder cases. An extended anatomical grading using MRI identifies poor long-term outcomes when lesions involve the substantia nigra and mesencephalic tegmentum, enhancing specificity over CT alone.[1][31][32] Recent 2025 advancements incorporate AI-assisted classification, leveraging machine learning on MRI and DTI data to detect subtle DAI patterns with mean accuracies around 68% and sensitivities up to 80%, aiding in automated severity stratification for timely management. These models integrate multimodal data to refine grading beyond manual assessment, particularly for heterogeneous traumatic brain injuries.[33][34] Despite their utility, DAI grading systems face limitations, including overlap with other traumatic brain injury subtypes like contusions, which can confound classification, and a historical reliance on postmortem pathology that has shifted toward in vivo imaging for broader applicability. Ongoing refinements address these challenges to better align grades with functional outcomes.[1][31]Diagnosis

Clinical assessment

Clinical assessment of diffuse axonal injury (DAI) begins with a detailed history taking to identify the mechanism of injury and initial neurological status. High-energy rotational or acceleration-deceleration forces, such as those from motor vehicle collisions or falls from height, are classic precipitants, often resulting in immediate and prolonged loss of consciousness without a lucid interval.[1] The duration of unconsciousness is a key indicator; coma exceeding 6 hours strongly suggests DAI, particularly when accompanied by post-traumatic amnesia.[35] Amnesia is evaluated using tools like the Galveston Orientation and Amnesia Test (GOAT), which assesses orientation to person, place, and time, as well as recall of events before and after the injury, helping to quantify the extent of cognitive disruption.[36] The physical examination focuses on rapid evaluation of consciousness, brainstem function, and systemic stability to gauge injury severity and detect complications. The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is central, with scores of 8 or less indicating severe DAI in most cases, reflecting profound impairment in eye opening, verbal response, and motor obedience.[1] Pupillary responses are scrutinized for asymmetry or fixed dilation, as anisocoria occurs in about one-third of patients and signals potential brainstem involvement.[1] Motor and sensory testing reveals decorticate or decerebrate posturing in severe cases, though focal deficits are uncommon; dysautonomia, manifesting as tachycardia, hypertension, or hyperthermia, may also be evident.[1] Signs of raised intracranial pressure (ICP), such as Cushing's triad—hypertension with bradycardia and irregular respirations—warrant immediate attention, as they indicate evolving secondary injury.[37] In the intensive care unit (ICU), serial monitoring is essential to track neurological evolution and exclude concurrent injuries. Vital signs and full neurological examinations, including GCS and pupillary checks, are performed every 1 to 4 hours, allowing detection of delayed deterioration such as worsening coma or new focal signs.[38] A comprehensive trauma survey ensures identification and exclusion of other traumatic brain injuries or extracranial insults, like skull fractures or spinal injuries, which could confound the DAI presentation.[38] Diagnosing DAI clinically presents significant challenges due to its subtle nature, often lacking visible external trauma or focal mass effects. Reliance on high clinical suspicion is critical in comatose patients following high-velocity impacts, where the absence of overt signs can delay recognition and intervention.[1]Neuroimaging techniques

Computed tomography (CT) scanning serves as the initial neuroimaging modality for evaluating suspected diffuse axonal injury (DAI), primarily screening for associated hemorrhages, edema, or mass effect in acute traumatic brain injury. However, CT has limited sensitivity for detecting DAI, identifying only approximately 10-20% of lesions, particularly non-hemorrhagic ones, and typically reveals subtle hypodensities in the white matter or small petechial hemorrhages when present.[1][39] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered the gold standard for confirming and characterizing DAI due to its superior soft tissue contrast and ability to detect both hemorrhagic and non-hemorrhagic axonal damage. Conventional MRI sequences, such as T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), highlight perilesional edema and gliosis in the acute and subacute phases, while gradient-echo sequences identify microhemorrhages as hypointense foci. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is particularly useful in the hyperacute stage to detect cytotoxic edema from acute ischemia, appearing as hyperintense areas with corresponding low apparent diffusion coefficient values.[40][41][1] Advanced MRI techniques provide quantitative assessment of microstructural axonal disruption. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) measures fractional anisotropy (FA) to evaluate white matter integrity, where reduced FA values indicate axonal damage and correlate with the extent of shearing injury. Susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) enhances detection of hemosiderin deposits from microhemorrhages, demonstrating up to six times greater sensitivity than conventional gradient-echo sequences for hemorrhagic DAI lesions. Positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) assess metabolic activity and cerebral blood flow alterations secondary to axonal injury, revealing hypometabolism in affected regions, though their routine use remains limited to research settings due to availability and cost.[42][40][43] As of 2025, ultra-high-field 7T MRI has emerged as an advancement for DAI evaluation, offering enhanced resolution for microstructural details and improved visualization of traumatic microbleeds through optimized SWI, potentially aiding in earlier and more precise lesion characterization compared to standard 3T systems. Characteristic DAI findings across modalities include multifocal lesions at gray-white matter junctions, the corpus callosum (especially the splenium), and brainstem structures like the dorsolateral midbrain and superior cerebellar peduncles. Lesion evolution progresses from hyperacute DWI restriction and T2 hyperintensity (edema) in the first days, to hypointense microhemorrhages on SWI or gradient echo in the subacute phase, and eventual T2/FLAIR hyperintensities representing chronic gliosis or atrophy.[44][45][41]Management

Acute interventions

Initial management of diffuse axonal injury (DAI) prioritizes airway protection and hemodynamic stabilization to prevent secondary brain insults. Patients with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 8 or less require endotracheal intubation to secure the airway, as they are at high risk of aspiration and inadequate ventilation.[46] Fluid resuscitation is initiated to maintain euvolemia, with vasopressors such as norepinephrine used if hypotension persists, targeting a mean arterial pressure (MAP) above 70 mmHg.[1] Cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) is optimized at 60-70 mmHg through a combination of adequate MAP and intracranial pressure (ICP) control, as lower values increase the risk of cerebral ischemia.[47] ICP management is critical in severe DAI cases, particularly those with GCS less than 8, where invasive monitoring via an external ventricular drain or intraparenchymal sensor is recommended after neurosurgical consultation.[1] Tiered interventions begin with mild hyperventilation to achieve a PaCO2 of 35-40 mmHg, avoiding profound hypocapnia that could cause vasoconstriction.[48] Osmotherapy with mannitol (0.25-1 g/kg) or hypertonic saline (e.g., 3% NaCl bolus) is employed to reduce ICP, with serum osmolality monitored to prevent complications like renal failure.[49] For refractory ICP exceeding 20-22 mmHg, barbiturate coma using pentobarbital is induced to suppress metabolic demand, and decompressive craniectomy may be considered in cases of severe TBI with refractory ICP and evidence of mass effect, though its utility in purely diffuse injuries such as DAI is limited based on clinical trials.[50][51] Seizure prophylaxis is routinely administered in the acute phase to mitigate the risk of early posttraumatic seizures, which occur in up to 25% of severe TBI cases including DAI.[52] Either phenytoin (loading dose 15-20 mg/kg IV, maintenance 5 mg/kg/day) or levetiracetam (loading 20-60 mg/kg IV, maintenance 1000-3000 mg/day) is initiated upon admission and continued for 7 days, as both agents demonstrate comparable efficacy in preventing early seizures without clear superiority.[53] Continuous EEG monitoring is advised for patients with altered mental status to detect non-convulsive status epilepticus, which can exacerbate secondary injury. Neuroprotective strategies emphasize avoiding hypoxia (target SpO2 >94%) and hypotension, which independently worsen outcomes in DAI by promoting ischemia and excitotoxicity.[1] Therapeutic hypothermia, targeting core temperatures of 32-34°C for 48-72 hours, has been investigated for its potential to reduce metabolic rate and inflammation, but evidence remains mixed as of 2025, with randomized trials showing no consistent mortality benefit and risks of complications like coagulopathy.[54] Current guidelines do not recommend routine use outside of clinical trials.[55]Rehabilitation and support

Rehabilitation for diffuse axonal injury (DAI) survivors emphasizes a multidisciplinary approach to address the widespread neurological deficits resulting from axonal shearing, with interventions beginning as early as the intensive care unit (ICU) to optimize long-term functional recovery.[1] Multidisciplinary teams typically include physical therapists who focus on improving mobility and balance through targeted exercises, occupational therapists who assist in regaining activities of daily living such as dressing and meal preparation, and speech-language pathologists who target communication and swallowing impairments.[56] Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is integrated to manage persistent cognitive deficits like attention and memory issues, often starting in the ICU and continuing through inpatient and outpatient phases to promote neuroplasticity and adaptive strategies.[57] Pharmacological support plays a key role in enhancing arousal and addressing neuropsychiatric sequelae in DAI recovery. As of 2025, no targeted pharmacological therapies exist to directly repair axonal damage in DAI; management remains supportive with agents aimed at symptom control and recovery enhancement.[1] Stimulants such as amantadine are commonly used to accelerate functional and cognitive recovery in patients with disorders of consciousness post-TBI, with evidence from randomized trials showing improved pace of recovery during treatment.[58] Antidepressants, particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), are prescribed for mood disorders like depression, which affect up to 50% of TBI survivors, helping to mitigate emotional dysregulation without exacerbating cognitive symptoms.[59] The 2025 American College of Surgeons guidelines for TBI management underscore the importance of personalized pharmacological regimens, tailored to individual injury severity and comorbidities, to support ongoing rehabilitation efforts.[38] Assistive technologies have emerged as vital tools to facilitate motor retraining and community participation for DAI patients. Neuroprosthetics, such as functional electrical stimulation devices, aid in restoring motor function by stimulating spared neural pathways, with studies demonstrating enhanced functional outcomes in severe TBI cases including DAI.[60] Virtual reality (VR) systems provide immersive environments for motor and cognitive rehabilitation, promoting neuroplasticity through repetitive, task-specific simulations that improve balance and executive function in a controlled yet engaging manner.[61] Community reintegration programs incorporate these technologies alongside vocational training to bridge the gap between clinical rehabilitation and real-world application, helping survivors adapt to daily challenges.[62] Family and psychosocial support are essential components of DAI rehabilitation, addressing the emotional toll on both survivors and caregivers while tackling barriers to societal reintegration. Counseling services, including family therapy, help navigate the psychological adjustments required after injury, fostering resilience and reducing caregiver burden through structured support groups.[63] Legal aid for disability claims is often provided to assist with accessing benefits, given the high unemployment rate among TBI survivors—estimated at 60-80% in working-age individuals due to cognitive and physical limitations.[64] These supports emphasize holistic recovery, integrating psychosocial interventions to improve quality of life and prevent isolation in the post-acute phase.[65]Prognosis

Outcome predictors

The severity of diffuse axonal injury (DAI) is a primary determinant of outcome, with higher grades associated with increased mortality and disability. Patients with grade III DAI, characterized by brainstem involvement, exhibit mortality rates ranging from 40% to 50%, alongside a high likelihood of persistent vegetative states or severe disability among survivors.[66] Initial Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores below 5 strongly correlate with poor functional recovery, where approximately 70% of patients achieve unfavorable outcomes on the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS 1-3) at 6 months.[67] Demographic and injury-related factors further modulate prognosis in DAI. Advanced age greater than 65 years approximately doubles in-hospital mortality compared to younger adults, due to reduced physiological reserve and comorbidities.[68] Pupillary abnormalities, such as fixed or non-reactive pupils on admission, are robust indicators of worse outcomes, reflecting brainstem dysfunction and reduced odds of favorable recovery.[1] Similarly, hypotension at the scene or during initial resuscitation exacerbates secondary brain injury, significantly increasing the risk of death or severe disability.[69] Post-traumatic hypoxia is associated with worse outcomes by amplifying ischemic damage to already vulnerable axons.[70] Serum biomarkers provide objective insights into axonal integrity and predict severity in DAI. Elevated levels of S100B and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in the acute phase indicate extensive axonal damage and correlate with poorer neurological recovery, as demonstrated in recent evaluations of neural injury markers.[71] Neuron-specific enolase (NSE) levels exceeding 20 ng/mL are indicative of severe DAI and associated with higher mortality, according to meta-analyses synthesizing biomarker data from traumatic brain injury cohorts.[72] Statistical models enhance prognostic accuracy by integrating multiple variables. The IMPACT calculator, derived from large traumatic brain injury databases, combines age, admission GCS, and pupillary reactivity—along with CT findings and laboratory data—to estimate 6-month mortality and unfavorable outcomes (GOS 1-4) with good calibration in moderate to severe cases, including those with DAI.[73] As referenced earlier, DAI grading systems align with these predictions, where higher grades amplify the model's risk estimates. A 2025 study of long-term outcomes in moderate to severe DAI reported that approximately one-third of patients achieve favorable outcomes, with half showing changes over time.[74]Long-term complications

Survivors of diffuse axonal injury (DAI) often face significant neurological complications that persist long after the initial trauma. Post-traumatic epilepsy is a common issue, with studies indicating a risk of 10-20% in severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) cases involving DAI, attributed to widespread axonal disruption and resultant cortical hyperexcitability.[75] Spasticity, characterized by increased muscle tone and involuntary contractions, affects up to 50% of severe TBI survivors with DAI, leading to mobility limitations and requiring ongoing management.[76] Chronic pain syndromes, including central neuropathic pain, occur in 30-65% of TBI patients with axonal injury, stemming from altered pain processing pathways in the brain.[77] In severe cases, DAI can contribute to parkinsonism or dementia-like syndromes due to progressive axonal degeneration and tau pathology accumulation.[78] Cognitive and psychological impairments represent another major domain of long-term morbidity in DAI. Memory impairment and executive dysfunction are prevalent, affecting approximately 50% of survivors to a moderate or severe degree, as a result of disrupted frontotemporal networks and white matter integrity loss.[79] Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression have an incidence of around 40% in TBI cohorts with DAI, linked to both direct brain injury and secondary psychosocial stressors.[80] Systemic effects from DAI extend beyond the central nervous system, with pituitary damage causing hormonal disruptions in 20-50% of severe cases; growth hormone deficiency is the most frequent, followed by adrenocorticotropic hormone and gonadotropin deficits, leading to fatigue, metabolic issues, and reduced quality of life.[81] Recent 2025 research highlights DAI's role in accelerated neurodegeneration, with axonal injury predicting amyloid and tau accumulation, elevating risks for Alzheimer's-like pathology and stroke by 2-3 fold compared to non-injured populations.[82][83] Overall, these complications profoundly impact quality of life, with 30-50% of DAI survivors requiring lifelong care and exhibiting dependency in daily activities, alongside substantial socioeconomic burdens such as unemployment rates exceeding 60% and increased healthcare utilization.[84][85]History

Early discoveries

Early observations of pathological changes in the brain's white matter following head trauma laid the groundwork for later identification of diffuse axonal injury (DAI), though the specific term was not yet in use. In the 1940s, Cyril B. Courville conducted detailed histological examinations of brains from fatal head injuries, noting widespread alterations in white matter, including fiber degeneration and reactive gliosis, often associated with commotio cerebri in non-penetrating trauma cases. These findings highlighted diffuse damage beyond focal contusions but were limited to postmortem analysis and did not yet emphasize axonal shearing as the primary mechanism. Key advancements came in the mid-1950s through autopsy studies of non-missile head injuries, which revealed microscopic tears in axons. Richard Lindenberg and Else Freytag analyzed cases of blunt force trauma, identifying linear hemorrhages and disruptions in the corpus callosum and subcortical white matter, termed "gliding contusions," where mechanical shearing caused axonal retraction balls and fiber breaks without gross external wounds. Their work, based on over 100 autopsies, demonstrated that such injuries occurred in acceleration-deceleration scenarios, common in civilian accidents, and were responsible for coma and persistent deficits independent of vascular rupture. In 1956, Sabina J. Strich provided further evidence in a series of five autopsied cases, describing diffuse degeneration of the cerebral white matter leading to severe dementia and neurological impairments months to years post-injury. Strich linked these outcomes to primary shearing of axons at the gray-white matter interface in patients who had experienced closed-head concussions, observing Marchi-positive degeneration and retraction bulbs as hallmarks of widespread axonal disruption. Her observations underscored the role of rotational forces in producing these lesions, distinguishing them from ischemic or vascular damage. Early terminology for these injuries often encompassed "diffuse vascular injury" due to accompanying petechial hemorrhages along axonal tracts, but evolving autopsy evidence shifted emphasis to the axonal component as the dominant pathology. Diagnosis remained confined to histopathological examination, as antemortem imaging was unavailable, limiting clinical recognition. These discoveries were contextualized by increases in forensic pathology studies following World War II, driven by rising road traffic accidents.Evolution of understanding

The understanding of diffuse axonal injury (DAI) evolved significantly from the mid-20th century onward, shifting from postmortem observations to advanced in vivo diagnostics and therapeutic explorations. In the 1970s and 1980s, early animal models laid the groundwork by demonstrating axotomy as a key pathological feature, with foundational work by researchers like John T. Povlishock using fluid percussion and impact acceleration models in rodents and primates to reveal primary axolemmal disruptions and secondary cytoskeletal changes leading to axonal disconnection. This built on earlier histological insights into axonal degeneration, emphasizing shear-strain-induced damage without gross focal lesions. By the 1980s, Thomas A. Gennarelli's pivotal 1982 primate studies using non-impact rotational acceleration models confirmed DAI as a distinct entity causing traumatic coma, coining the term "diffuse axonal injury" and establishing its role in prolonged unconsciousness through widespread white matter shearing. These experiments introduced an initial grading framework correlating injury severity with acceleration direction and magnitude, grading I for subcortical lesions, II for corpus callosum involvement, and III for brainstem extension, which became a cornerstone for prognostic assessment. The 1990s and 2000s marked a diagnostic revolution with the advent of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), enabling non-invasive detection of DAI previously reliant on autopsy. Early MRI studies in the 1990s identified hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted sequences in white matter tracts, but DTI, introduced clinically around 2000, quantified microstructural damage via fractional anisotropy reductions, as demonstrated in Arfanakis et al.'s 2002 study of mild TBI patients showing decreased anisotropy in corpus callosum and internal capsules within 24 hours post-injury. Concurrently, biomechanical modeling advanced through finite element analysis of head impacts, simulating strain thresholds for axotomy (e.g., >15-25% strain) and validating animal data against human cadaveric responses, which refined injury tolerance criteria and informed crash safety standards. These tools shifted focus from fatal outcomes to subtle, diffuse pathologies in survivors. From the 2010s to 2025, research emphasized biomarkers, neuroprotection, and computational prognostics, reflecting a paradigm transition from viewing DAI as invariably fatal to recognizing axonal plasticity and long-term sequelae like chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Serum ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) emerged as a key biomarker for axonal injury, with levels rising within hours of TBI and correlating with DAI severity on imaging, as shown in multiple cohort studies where UCH-L1 elevations predicted poor outcomes independent of CT findings. Neuroprotective trials, such as those testing therapeutic hypothermia, largely failed to improve outcomes; for instance, randomized controlled trials in severe TBI patients with DAI components reported no reduction in mortality or disability despite cooling to 32-34°C, highlighting challenges in timing and secondary injury mitigation. Artificial intelligence integration in neuroimaging advanced prognostic accuracy, with machine learning models analyzing DTI and CT data to predict 6-month functional independence (e.g., Glasgow Outcome Scale) with >85% sensitivity by detecting subtle white matter disruptions missed by clinicians. Recent classification advancements, such as the 2023 American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine (ACRM) diagnostic criteria for mild traumatic brain injury refining assessment of subtle axonal damage and the 2024 American College of Surgeons (ACS) best practice guidelines emphasizing multidisciplinary rehabilitation for TBI, supported multimodal assessment for personalized care. This era underscored brain plasticity, with evidence from longitudinal studies showing partial axonal sprouting in mild DAI cases and links to CTE via repetitive shearing promoting tau pathology, prompting a reevaluation of DAI as a chronic, modifiable condition rather than an acute death sentence.Notable cases

Several high-profile individuals have suffered diffuse axonal injury (DAI) from traumatic incidents, highlighting the condition's severity. In 2006, British television presenter Richard Hammond sustained a DAI during a high-speed crash while filming Top Gear, when a jet-powered car he was driving at approximately 300 mph (480 km/h) rolled over; he was in a coma for two weeks and underwent extensive rehabilitation.[86] Colombian racing driver Roberto Guerrero experienced severe DAI in September 1987 during tire testing at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, where his car hit the wall and a detached tire struck his helmet, causing his brain to bounce within the skull; he remained in a coma for several days but remarkably returned to racing the following year.[87] French Formula One driver Jules Bianchi suffered a fatal DAI in October 2014 after crashing into a recovery vehicle during the Japanese Grand Prix at Suzuka Circuit due to aquaplaning on a wet track; he remained in a coma until his death in July 2015.[88]References

- https://www.wikem.org/wiki/Moderate-to-severe_traumatic_brain_injury