Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Moksha language

View on Wikipedia| Moksha | |

|---|---|

| Mokshan[1] | |

| мокшень кяль mokšəń käĺ | |

| Pronunciation | ['mɔkʃənʲ kælʲ] |

| Native to | Russia |

| Region | European Russia |

| Ethnicity | 253,000 Mokshas (2010 census) |

Native speakers | 23,000 (2020 census)[2] |

| Cyrillic | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Mordovia (Russia) |

| Regulated by | Mordovian Research Institute of Language, Literature, History and Economics |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | mdf |

| ISO 639-3 | mdf |

| Glottolog | moks1248 |

| ELP | Moksha |

| |

Moksha is classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger. | |

Moksha (мокшень кяль, mokšəń käĺ, pronounced ['mɔkʃənʲ kælʲ]) is a Mordvinic language of the Uralic family, spoken by Mokshas, with around 130,000 native speakers in 2010. Moksha is the majority language in the western part of Mordovia.[5] Its closest relative is the Erzya language, with which it is not mutually intelligible. Moksha is also possibly closely related to the extinct Meshcherian and Muromian languages.[6]

History

[edit]Cherapkin's Inscription

[edit]There is very little historical evidence of the use of Moksha from the distant past. One notable exception are inscriptions on so-called mordovka silver coins issued under Golden Horde rulers around the 14th century. The evidence of usage of the language (written with the Cyrillic script) comes from the 16th century.[7][8]

МОЛИ

moli

Моли

АНСИ

ansi

аньцек

ОКАНП

okan

окань

ЄЛКИ

pelki

пяли

(Inscription, Old Moksha)

(Transcription)

(Interpretation, Moksha)

Goes only for half gold

Indo-Iranian Influence

[edit]| Indo-Iranian forms | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| D–V | |||

| Indo-Iranian form | Declining stem | Meaning | Moksha derivatives |

| داس | Persian: dâs | "sickle" | тарваз /'tɑrvɑs/ "sickle"[9] |

| 𐬠𐬀𐬖𐬀 | Avestan: baγa | "God" | паваз /'pɑvɑs/ "God"[10] |

| ऊधर् | Sanskrit: ū́dhar | "udder" | одар /'odɑr/ "udder"[10] |

| वज्र | Sanskrit: vajra | "God's weapon" | узерь /'uzʲərʲ/ "axe"[11] |

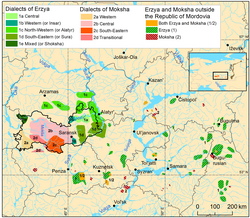

Dialects

[edit]

The Moksha language is divided into three dialects:

- Central group (M-I)

- Western group (M-II)

- South-Eastern group (M-III)

The dialects may be divided with another principle depending on their vowel system:

- ä-dialect: Proto-Moksha *ä /æ/ is retained: śeĺmä /sʲelʲmæ/ "eye", t́äĺmä /tʲælʲmæ/ "broom", ĺäj /lʲæj/ "river".

- e-dialect: Proto-Moksha *ä is raised and merged with *e: śeĺme /sʲelʲme/ "eye", t́eĺme /tʲelʲme/ "broom", ĺej /lʲej/ "river". The South-Eastern group belongs to the e-dialect

- i-dialect: Proto-Moksha *ä is raised to /e/, while Proto-Moksha *e is raised to /i/ and merged with *i: śiĺme /sʲilʲme/ "eye", t́eĺme /tʲelʲme/ "broom", ĺej /lʲej/ "river".

The standard literary Moksha language is based on the central group with ä (particularly the dialect of Krasnoslobodsk).

Sociolinguistics

[edit]Official status

[edit]

Moksha is one of the three official languages in Mordovia (the others being Erzya and Russian). The right to one's own language is guaranteed by the Constitution of the Mordovia Republic.[12] The republican law of Mordovia N 19-3 issued in 1998[13] declares Moksha one of its state languages and regulates its usage in various spheres: in state bodies such as Mordovian Parliament, official documents and seals, education, mass-media, information about goods, geographical names, road signs. However, the actual usage of Moksha and Erzya is rather limited.

Revitalisation efforts in Mordovia

[edit]Policies regarding the revival of the Moksha and Erzya languages in Mordovia started in the late 1990s, when the Language, and Education Laws were accepted. From the early 2000s on, the policy goal has been to create a unified Mordvin standard language despite differences between Erzya and Moksha.[14]

However, there have been no executive programmes for the implementation of the Language Law. Only about a third of Mordvin students had access to Mordvin language learning, the rest of whom are educated through Russian. Moksha has been used as the medium of instruction in some rural schools, but the number of students attending those schools is in rapid decline. In 2004, Mordovian authorities attempted to introduce compulsory study of the Mordvin/Moksha as one of the Republic's official languages, but this attempt failed in the aftermath of the 2007 education reform in Russia.

Phonology

[edit]Vowels

[edit]There are eight vowels with limited allophony and reduction of unstressed vowels. Moksha has lost the original Uralic system of vowel harmony but maintains consonant-vowel harmony (palatalized consonants go with front vowels, non-palatalized with non-front).

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i ⟨и⟩ |

ɨ ⟨ы⟩ |

u ⟨у, ю⟩ |

| Mid | e ⟨е, э⟩ |

ə ⟨а, о, е⟩ |

o ⟨о⟩ |

| Open | æ ⟨я, э, е⟩ |

ɑ ⟨а⟩ |

There are some restrictions for the occurrence of vowels within a word:[15]

- [ɨ] is an allophone of the phoneme /i/ after phonemically non-palatalized ("hard") consonants.[16]

- /e/ does not occur after non-palatalized consonants, only after their palatalized ("soft") counterparts.

- /a/ and /æ/ do not fully contrast after phonemically palatalized or non-palatalized consonants.[clarification needed]

- Similar to /e/, /æ/ does not occur after non-palatalized consonants either, only after their palatalized counterparts.

- After palatalized consonants, /æ/ occurs at the end of words, and when followed by another palatalized consonant.

- /a/ after palatalized consonants occurs only before non-palatalized consonants, i.e. in the environment /CʲaC/.

- The mid vowels' occurrence varies by the position within the word:

- In native words, /e, o/ are rare in the second syllable, but common in borrowings from e.g. Russian.

- /e, o/ are never found in the third and following syllables, where only /ə/ occurs.

- /e/ at the end of words is only found in one-syllable words (e.g. ве /ve/ "night", пе /pe/ "end"). In longer words, word-final ⟨е⟩ always stands for /æ/ (e.g. веле /velʲæ/ "village", пильге /pilʲɡæ/ "foot, leg").[17]

Unstressed /ɑ/ and /æ/ are slightly reduced and shortened [ɑ̆] and [æ̆] respectively.

Consonants

[edit]There are 33 consonants in Moksha.

| Labial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | palat. | |||||||||||

| Nasal | m ⟨м⟩ |

n ⟨н⟩ |

nʲ ⟨нь⟩ |

|||||||||

| Stop | p ⟨п⟩ |

b ⟨б⟩ |

t ⟨т⟩ |

d ⟨д⟩ |

tʲ ⟨ть⟩ |

dʲ ⟨дь⟩ |

k ⟨к⟩ |

ɡ ⟨г⟩ | ||||

| Affricate | ts ⟨ц⟩ |

tsʲ ⟨ць⟩ |

tɕ ⟨ч⟩ |

|||||||||

| Fricative | f ⟨ф⟩ |

v ⟨в⟩ |

s ⟨с⟩ |

z ⟨з⟩ |

sʲ ⟨сь⟩ |

zʲ ⟨зь⟩ |

ʂ~ʃ ⟨ш⟩ |

ʐ~ʒ ⟨ж⟩ |

ç ⟨йх⟩ |

x ⟨х⟩ |

||

| Approximant | l̥ ⟨лх⟩ |

l ⟨л⟩ |

l̥ʲ ⟨льх⟩ |

lʲ ⟨ль⟩ |

j ⟨й⟩ |

|||||||

| Trill | r̥ ⟨рх⟩ |

r ⟨р⟩ |

r̥ʲ ⟨рьх⟩ |

rʲ ⟨рь⟩ |

||||||||

/ç/ is realized as a sibilant [ɕ] before the plural suffix /-t⁽ʲ⁾/ in south-east dialects.[18]

Palatalization, characteristic of Uralic languages, is contrastive only for dental consonants, which can be either "soft" or " hard". In Moksha Cyrillic alphabet the palatalization is designated like in Russian: either by a "soft sign" ⟨ь⟩ after a "soft" consonant or by writing "soft" vowels ⟨е, ё, и, ю, я⟩ after a "soft" consonant. In scientific transliteration the acute accent or apostrophe are used.

All other consonants have palatalized allophones before the front vowels /æ, i, e/ as well. The alveolo-palatal affricate /tɕ/ lacks non-palatalized counterpart, while postalveolar fricatives /ʂ~ʃ, ʐ~ʒ/ lack palatalized counterparts.

Devoicing

[edit]Unusually for a Uralic language, there is also a series of voiceless liquid consonants: /l̥ , l̥ʲ, r̥ , r̥ʲ/ ⟨ʀ, ʀ́, ʟ, ʟ́⟩. These have arisen from Proto-Mordvinic consonant clusters of a sonorant followed by a voiceless stop or affricate: *p, *t, *tʲ, *ts⁽ʲ⁾, *k.

Before certain inflectional and derivational endings, devoicing continues to exist as a phonological process in Moksha. This affects all other voiced consonants as well, including the nasal consonants and semivowels. No voiceless nasals are however found in Moksha: the devoicing of nasals produces voiceless oral stops. Altogether the following devoicing processes apply:

| Plain | b | m | d | n | dʲ | nʲ | ɡ | l | lʲ | r | rʲ | v | z | zʲ | ʒ | j |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Devoiced | p | t | tʲ | k | l̥ | l̥ʲ | r̥ | r̥ʲ | f | s | sʲ | ʃ | ç | |||

For example, before the nominative plural /-t⁽ʲ⁾/:

- кал /kal/ "fish" – калхт /kal̥t/ "fish"

- лем /lʲem/ "name" – лепть /lʲeptʲ/ "names"

- марь /marʲ/ "apple" – марьхть /mar̥ʲtʲ/ "apples"

Devoicing is, however, morphological rather than phonological, due to the loss of earlier voiceless stops from some consonant clusters, and due to the creation of new consonant clusters of voiced liquid + voiceless stop. Compare the following oppositions:

- калне /kalnʲæ/ "little fish" – калхне /kal̥nʲæ/ (< *kal-tʲ-nʲæ) "these fish"

- марьне /marʲnʲæ/ "my apples" – марьхне /mar̥ʲnʲæ/ ( < *marʲ-tʲ-nʲæ) "these apples"

- кундайне /kunˈdajnʲæ/ "I caught it" – кундайхне /kunˈdaçnʲæ/ ( < *kunˈdaj-tʲ-nʲæ) "these catchers"

Stress

[edit]Non-high vowels are inherently longer than high vowels /i, u, ə/ and tend to draw the stress. If a high vowel appears in the first syllable which follow the syllable with non-high vowels (especially /a/ and /æ/), then the stress moves to that second or third syllable. If all the vowels of a word are either non-high or high, then the stress falls on the first syllable.[19]

Stressed vowels are longer than unstressed ones in the same position like in Russian. Unstressed vowels undergo some degree of vowel reduction.

Writing systems

[edit]

Moksha has been written using Cyrillic with spelling rules identical to those of Russian since the 18th century. As a consequence of that, the vowels /e, ɛ, ə/ are not differentiated in a straightforward way.[20] However, they can be (more or less) predicted from Moksha phonotactics. The 1993 spelling reform defines that /ə/ in the first (either stressed or unstressed) syllable must be written with the "hard" sign ⟨ъ⟩ (e.g. мъ́рдсемс mə́rdśəms "to return", formerly мрдсемс). The version of the Moksha Cyrillic alphabet used in 1924-1927 had several extra letters, either digraphs or single letters with diacritics.[21] Although the use of the Latin script for Moksha was officially approved by the CIK VCKNA (General Executive Committee of the All Union New Alphabet Central Committee) on June 25, 1932, it was never implemented.

| Cyr | Аа | Бб | Вв | Гг | Дд | Ее | Ёё | Жж | Зз | Ии | Йй | Кк | Лл | Мм | Нн | Оо | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | a | b | v | ɡ | d | ʲe, | je, | ʲɛ, | ʲə | ʲo, | jo | ʒ | z | i | j | k | l | m | n | o, | ə |

| ScTr | a | b | v | g | d | ˊe, | je, | ˊä, | ˊə | ˊo, | jo | ž | z | i | j | k | l | m | n | o, | ə |

| Cyr | Пп | Рр | Сс | Тт | Уу | Фф | Хх | Цц | Чч | Шш | Щщ | Ъъ | Ыы | Ьь | Ээ | Юю | Яя | ||||

| IPA | p | r | s | t | u | f | x | ts | tɕ | ʃ | ɕtɕ | ə | ɨ | ʲ | e, | ɛ | ʲu, | ju | ʲa, | æ, | ja |

| ScTr | p | r | s | t | u | f | χ | c | č | š | šč | ə | i͔ | ˊ | e, | ä | ˊu, | ju | ˊa, | ˊä, | ja |

| IPA | a | ʲa | ja | ɛ | ʲɛ | b | v | ɡ | d | dʲ | e | ʲe | je | ʲə | ʲo | jo | ʒ | z | zʲ | i | ɨ | j | k | l | lʲ | l̥ | l̥ʲ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyr | а | я | я | э | я, | е | б | в | г | д | дь | э | е | е | е | ё | ё | ж | з | зь | и | ы | й | к | л | ль | лх | льх |

| ScTr | a | ˊa | ja | ä | ˊä | b | v | g | d | d́ | e | ˊe | je | ˊə | ˊo | jo | ž | z | ź | i | i͔ | j | k | l | ľ | ʟ | ʟ́ | |

| IPA | m | n | o | p | r | rʲ | r̥ | r̥ʲ | s | sʲ | t | tʲ | u | ʲu | ju | f | x | ts | tsʲ | tɕ | ʃ | ɕtɕ | ə | |||||

| Cyr | м | н | о | п | р | рь | рх | рьх | с | сь | т | ть | у | ю | ю | ф | х | ц | ць | ч | ш | щ | о, | ъ,* | a,* | и* | ||

| ScTr | m | n | o | p | r | ŕ | ʀ | ʀ́ | s | ś | t | t́ | u | ˊu | ju | f | χ | c | ć | č | š | šč | ə | |||||

Grammar

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding missing information. (July 2014) |

Morphosyntax

[edit]Like other Uralic languages, Moksha is an agglutinating language with elaborate systems of case-marking and conjugation, postpositions, no grammatical gender, and no articles.[22]

Case

[edit]Moksha has 13 productive cases, many of which are primarily locative cases. Locative cases in Moksha express ideas that Indo-European languages such as English normally code by prepositions (in, at, towards, on, etc.).

However, also similarly to Indo-European prepositions, many of the uses of locative cases convey ideas other than simple motion or location. These include such expressions of time (e.g. on the table/Monday, in Europe/a few hours, by the river/the end of the summer, etc. ), purpose (to China/keep things simple), or beneficiary relations. Some of the functions of Moksha cases are listed below:

- Nominative, used for subjects, predicatives and for other grammatical functions.

- Genitive, used to code possession.

- Allative, used to express the motion onto a point.

- Elative, used to code motion out of a place.

- Inessive, used to code a stationary state, in a place.

- Ablative, used to code motion away from a point or a point of origin.

- Illative, used to code motion into a place.

- Translative, used to express a change into a state.

- Prolative, used to express the idea of "by way" or "via" an action or instrument.

- Lative, used to code motion towards a place.

There is controversy about the status of the three remaining cases in Moksha. Some researchers see the following three cases as borderline derivational affixes.

- Comparative, used to express a likeness to something.

- Caritive (or abessive), used to code the absence of something.

- Causal, used to express that an entity is the cause of something else.

| Case function | Case Name[22] | Suffix | Vowel stem | Plain consonant stem | Palatalized consonant stem | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [ˈmodɑ] | land | [kut] | house | [velʲ] | town | |||

| Grammatical | Nominative | -Ø | [ˈmodɑ] | a land | [kud] | a house | [ˈvelʲæ] | a town |

| Genitive | [nʲ] | [ˈmodɑnʲ] | of a land, a land's | [ˈkudʲənʲ] | of a house, a house's | [ˈvelʲənʲ] | of a town, a town's | |

| Locative | Allative | [nʲdʲi] | [ˈmodɑnʲdʲi] | onto a land | [ˈkudənʲdʲi] | onto a house | [ˈvelʲənʲdʲi] | onto a town |

| Elative | [stɑ] | [ˈmodɑstɑ] | out of a land | [kutˈstɑ] | out of a house | [ˈvelʲəstɑ] | out of a town | |

| Inessive | [sɑ] | [ˈmodɑsɑ] | in a land | [kutˈsɑ] | in a house | [ˈvelʲəsɑ] | in a town | |

| Ablative | [dɑ, tɑ] | [ˈmodɑdɑ] | from a land | [kutˈtɑ] | from the house | [ˈvelʲədɑ] | from the town | |

| Illative | [s] | [ˈmodɑs] | into a land | [kuts] | into a house | [ˈvelʲəs] | into a town | |

| Prolative | [vɑ, ɡɑ] | [ˈmodɑvɑ] | through/alongside a land | [kudˈɡɑ] | through/alongside a house | [ˈvelʲəvɑ] | through/alongside a town | |

| Lative | [v, u, i] | [ˈmodɑv] | towards a land | [ˈkudu] | towards a house | [ˈvelʲi] | towards a town | |

| Other | Translative | [ks] | [ˈmodɑks] | becoming/as a land | [ˈkudəks] | becoming/as a house | [ˈvelʲəks] | becoming a town, as a town |

| Comparative | [ʃkɑ] | [ˈmodɑʃkɑ] | size of a land, land size | [kudəʃˈkɑ] | size of a house, house size | [ˈvelʲəʃkɑ] | size of a town, town size | |

| Caritive | [ftəmɑ] | [ˈmodɑftəmɑ] | without a land, landless | [kutftəˈmɑ] | without a house, houseless | [ˈvelʲəftəma] | without a town, townless | |

| Causal | [ŋksɑ] | [ˈmodɑŋksɑ] | because of a land | [kudəŋkˈsɑ] | because of a house | [ˈvelʲəŋksɑ] | because of a town | |

Relationships between locative cases

[edit]As in other Uralic languages, locative cases in Moksha can be classified according to three criteria: the spatial position (interior, surface, or exterior), the motion status (stationary or moving), and within the latter, the direction of the movement (approaching or departing). The table below shows these relationships schematically:

| Spatial Position | Motion Status | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stationary | Moving | ||

| Approaching | Departing | ||

| Interior | inessive (in)

[-sɑ] |

illative (into)

[-s] |

elative (out of)

[stɑ] |

| Surface | N/A | allative (onto)

[nʲdʲi] |

ablative (from)

[dɑ, tɑ] |

| Exterior | prolative (by)

[vɑ, gɑ] |

lative (towards)

[v, u, i] |

N/A |

Pronouns

[edit]| Case | Singular | Plural | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | Third | First | Second | Third | |

| nominative | [mon] | [ton] | [son] | [minʲ] | [tʲinʲ] | [sʲinʲ] |

| genitive | [monʲ] | [tonʲ] | [sonʲ] | |||

| allative | [monʲdʲəjnʲæ, tʲejnæ] | [ˈtonʲdʲəjtʲ, tʲəjtʲ] | [ˈsonʲdʲəjzɑ, ˈtʲejnzɑ] | [minʲdʲəjnʲek] | [tinʲdʲəjnʲtʲ] | [sʲinʲdʲəst] |

| ablative | [ˈmonʲdʲədən] | [ˈtonʲdʲədət] | [ˈsonʲdʲədənzɑ] | [minʲdʲənk] | [minʲdʲədent] | [sʲinʲdʲədəst] |

Common expressions

[edit]| Moksha | Romanization | English |

|---|---|---|

| Да | Da | Yes |

| Пара | Pára | Good |

| Стане | Stáne | Right |

| Аф | Af | Not |

| Аш | Aš | No |

| Шумбра́т! | Šumbrát! | Hello! (addressing one person) |

| Шумбра́тада! | Šumbrátada! | Hello! (addressing more than one person) |

| Сюкпря! | Sjuk prjá! | Thanks! (lit.: Bow) |

| Ульхть шумбра́! | Ulht šumbrá! | Bless you! |

| У́леда шумбра́т! | Úleda šumbrát! | Bless you (to many)! |

| Ванфтт пря́цень! | Vanft prjátsen | Take care! |

| Ванфтк пря́цень! | Vanftk prjátsen! | Be careful! |

| Ко́да э́рят? | Kóda érjat? | How do you do? |

| Ко́да те́фне? | Kóda téfne? | How are your things getting on? |

| Лац! | Lac! | Fine! |

| Це́бярьста! | Cébjarsta! | Great! |

| Ня́емозонк! | Njájemozonk! | Good bye! (lit.: See you later) |

| Ва́ндыс! | Vándis! | See you tomorrow! |

| Шумбра́ста па́чкодемс! | Šumbrásta páčkodems! | Have a good trip/flight! |

| Па́ра а́зан - ле́здоманкса! - се́мбонкса! |

Pára ázan - lézdomanksa! - sémbonksa! |

Thank you - for help/assistance! - for everything! |

| Аш ме́зенкса! | Aš mézenksa! | Not at all! |

| Про́стямак! | Prо́stjamak! | I'm sorry! |

| Про́стямасть! | Prо́stjamast! | I'm sorry (to many)! |

| Тят кяжия́кшне! | Tját kjažijákšne! | I didn't mean to hurt you! |

| Ужя́ль! | Užjál! | It's a pity! |

| Ко́да тонь ле́мце? | Kóda ton lémce? | What is your name? |

| Монь ле́мозе ... | Mon lémoze ... | My name is ... |

| Мъзя́ра тейть ки́зa? | Mzjára téjt kíza? | How old are you? |

| Мъзя́ра те́йнза ки́за? | Mzjára téinza kíza? | How old is he (she)? |

| Те́йне ... ки́зот. | Téjne ... kízot. | I'm ... years old. |

| Те́йнза ... ки́зот. | Téjnza ... kízot. | He (she) is ... years old. |

| Мя́рьгат сува́мс? | Mjárgat suváms? | May I come in? |

| Мя́рьгат о́замс? | Mjárgat о́zams? | May I have a seat? |

| О́зак. | Ózak. | Take a seat. |

| О́зада. | Ózada. | Take a seat (to many). |

| Учт аф ла́мос. | Učt af lámos. | Please wait a little. |

| Мярьк та́ргамс? | Mjárk tárgams? | May I have a smoke? |

| Та́ргак. | Tárgak. | [You may] smoke. |

| Та́ргада. | Tárgada. | [You may] smoke (to many). |

| Аф, э́няльдян, тят та́рга. | Af, énjaldjan, tját tárga. | Please, don't smoke. |

| Ко́рхтак аф ла́мода ся́да ка́йгиста (сяда валомня). | Kórtak af lámoda sjáda kájgista (sjáda valо́mne). | Please speak a bit louder (lower). |

| Азк ни́нге весть. | Azk nínge vest. | Repeat one more time. |

| Га́йфтть те́йне. | Gájft téjne. | Call me. |

| Га́йфтеда те́йне. | Gájfteda téjne. | Call me (to many). |

| Га́йфтть те́йне ся́да ме́ле. | Gájft téjne sjáda méle. | Call me later. |

| Сува́к. | Suvák. | Come in. |

| Сува́да. | Suváda. | Come in (to many). |

| Ётак. | Jо́tak. | Enter. |

| Ётада. | Jо́tada. | Enter (to many). |

| Ша́чема ши́цень ма́рхта! | Šáčema šícen márhta! | Happy Birthday! |

| А́рьсян тейть па́ваз! | Ársjan téjt pávaz! | I wish you happiness! |

| А́рьсян тейть о́цю сатфкст! | Ársjan téjt ótsju satfkst! | I wish you great success! |

| Тонь шумбраши́цень и́нкса! | Ton šumbrašícen ínksa! | Your health! |

| О́чижи ма́рхта | Óčiži márhta! | Happy Easter! |

| Од Ки́за ма́рхта! | Od Kíza márhta! | Happy New Year! |

| Ро́штува ма́рхта! | Róštuva márhta! | Happy Christmas! |

| То́ньге ста́не! | Tónge stáne! | Same to you! |

Media

[edit]Use in literature

[edit]Before 1917 about 100 books and pamphlets mostly of religious character were published. More than 200 manuscripts including at least 50 wordlists were not printed. In the 19th century the Russian Orthodox Missionary Society in Kazan published Moksha primers and elementary textbooks of the Russian language for the Mokshas. Among them were two fascicles with samples of Moksha folk poetry. The great native scholar Makar Evsevyev collected Moksha folk songs published in one volume in 1897. Early in the Soviet period, social and political literature predominated among published works. Printing of Moksha language books was all done in Moscow until the establishment of the Mordvinian national district in 1928. Official conferences in 1928 and 1935 decreed the northwest dialect to be the basis for the literary language.

Use in education

[edit]The first few Moksha schools were established in the 19th century by Russian Christian missionaries. Since 1973, Moksha has been allowed to be used as the language of instruction for the first three grades of elementary school in rural areas, and as an elective subject.[23] Classes in universities in Mordovia are in Russian, but the philological faculties of Mordovian State University and Mordovian State Pedagogical Institute offer a teacher course of Moksha.[24][25] Mordovian State University also offers a course in Moksha for other humanitarian and some technical specialities.[25] According to annual statistics from the Russian Ministry of Education for 2014-2015, there were 48 Moksha-medium schools (all in rural areas) where 644 students were taught, and 202 schools (152 in rural areas) where Moksha was studied as a subject by 15,783 students (5,412 in rural areas).[26] Since 2010, the study of Moksha in Mordovian schools is not compulsory, but can be chosen only by parents.[27]

References

[edit]- ^ Moksha language at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ "Итоги Всероссийской переписи населения 2020 года. Таблица 6. Население по родному языку" [Results of the All-Russian population census 2020. Table 6. population according to native language.]. rosstat.gov.ru. Retrieved 2023-01-03.

- ^ Rantanen, Timo; Tolvanen, Harri; Roose, Meeli; Ylikoski, Jussi; Vesakoski, Outi (2022-06-08). "Best practices for spatial language data harmonization, sharing and map creation—A case study of Uralic". PLOS ONE. 17 (6) e0269648. Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1769648R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0269648. PMC 9176854. PMID 35675367.

- ^ Rantanen, Timo, Vesakoski, Outi, Ylikoski, Jussi, & Tolvanen, Harri. (2021). Geographical database of the Uralic languages (v1.0) [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4784188

- ^ [1] Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Janse, Mark; Sijmen Tol; Vincent Hendriks (2000). Language Death and Language Maintenance. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. A108. ISBN 978-90-272-4752-0.

- ^ Зайковский Б. В. «К вопросу о мордовках» Труды Нижне-Волжского областного научного общества краеведения. Вып. 36, часть 1. Саратов, 1929 г

- ^ Вячеслав Юрьевич Заварюхин. Памятники нумизматики и бонистики в региональном историко-культурном процессе, автореферат диссертации, 2006

- ^ Vershinin 2009, p. 431

- ^ a b Vershinin 2005, p. 307

- ^ Vershinin 2005

- ^ (in Russian) Статья 12. Конституция Республики Мордовия = Article 12. Constitution of the Republic of Mordovia

- ^ (in Russian) Закон «О государственных языках Республики Мордовия»

- ^ Zamyatin, Konstantin (2022-03-24), "Language policy in Russia: The Uralic languages", The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages, Oxford University Press, pp. 79–90, doi:10.1093/oso/9780198767664.003.0005, ISBN 978-0-19-876766-4, retrieved 2022-10-18

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Feoktistov 1993, p. 182.

- ^ Feoktistov 1966, p. 200.

- ^ Feoktistov 1966, p. 200–201.

- ^ Feoktistov 1966, p. 220.

- ^ Raun 1988, p. 100.

- ^ Raun 1988, p. 97.

- ^ Omniglot.com page on the Moksha language

- ^ a b c (in Finnish) Bartens, Raija (1999). Mordvalaiskielten rakenne ja kehitys. Helsinki: Suomalais-ugrilaisen Seura. ISBN 952-5150-22-4. OCLC 41513429.

- ^ Kreindler, Isabelle T. (January–March 1985). "The Mordvinians: A doomed Soviet nationality?". Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique. 26 (1): 43–62. doi:10.3406/cmr.1985.2030.

- ^ (in Russian) Кафедра мокшанского языка Archived 2015-06-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b (in Russian) Исполняется 15 лет со дня принятия Закона РМ «О государственных языках Республики Мордовия» Archived 2015-06-14 at the Wayback Machine // Известия Мордовии. 12.04.2013.

- ^ "Статистическая информация 2014. Общее образование". Archived from the original on 2018-08-09. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ (in Russian) Прокуратура борется с нарушением законодательства об образовании = The Prosecutor of Mordovia prevents violations against the educational law. 02 February 2010.

Bibliography

[edit]- Aasmäe, Niina; Lippus, Pärtel; Pajusalu, Karl; Salveste, Nele; Zirnask, Tatjana; Viitso, Tiit-Rein (2013). Moksha prosody. Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran toimituksia. Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. ISBN 978-952-5667-47-9. Retrieved 2014-07-24.

- Feoktistov, Aleksandr; Saarinen, Sirkka (2005). Mokšamordvan murteet [Dialects of Moksha Mordvin]. Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran toimituksia (in Finnish). Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. ISBN 952-5150-86-0.

- Juhász, Jenő (1961). Moksa-Mordvin szójegyzék (in Hungarian). Budapest.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Paasonen, Heikki (1990–1999). Kahla, Martti (ed.). Mordwinisches Wörterbuch. Helsinki.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Raun, Alo (1988). "The Mordvin Language". In Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Uralic Languages: Description, History and Foreign Influences. BRILL. pp. 96–110. ISBN 90-04-07741-3.

- Kuznetsov, Stefan (1912), Russkaya istoricheskaya geografiya. Mordva (in Russian), Book on Demand Ltd, ISBN 5-518-06684-8

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Belyakov, Andrey (2013-03-12), Invisible Men in Russian Army in 16th century. Russian Army During the Reign of Ivan the Terrible. Materials of Academic Discussion Dedicated To 455th Anniversary of Beginning of the Livonian War. Part I. Is.2 (in Russian), Saint-Petersburg

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Fedorov-Davydov G.A.; Tsirkin A.V. (1966), Novye dannye ob Ityakovskom gorodishche v Temnikovskom r-ne Mordovskoy ASSR [New Data on the Ityakovskoe Settlement in the Temnikov District of the Mordovian ASSR]. Issledovaniya po arkheologii i etnografii Mordovskoy ASSR: Trudy Mordovskogo IYaLIE [Studies in Archaeology and Ethnography of the Mordovian ASSR: Proceedings of the Mordovian Scientific-Research Institute of Language, Literature and History] Is. 30 (in Russian), Saransk

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Filjushkin, Alexander (2008). Ivan the Terrible: A Military History. Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-84832-504-3.

- Geraklitov, Aleksandr (2011). Selected Works. Vol. 1. Mordovsky belyak (in Russian). Mordovia Republic Humanities Research Institute. ISBN 978-5-900029-78-8.

- Zaikovsky, Bogdan (1929), Back To Mordovkas' Problem (in Russian), Saratov: Nizhne-Volzhskaya Oblast scientific and historical society review

- Serebrenikov, B.A.; Feoktistov, A.P.; Polyakov, O.Y., eds. (1998) [First published 1998]. Moksha-Russian Dictionary (in Russian). Digora. ISBN 5-200-02012-3.

- Semenkovich, Vladimir (1913). Geloni and Mordva: Historical Geography Of Upper Don And Oka Materials and Research (in Russian). Yeltsin President Library.

- Orbelli, Iosif (1982). Folklore And Traditions of Moks (in Russian). Nauka.

- Popov, M.M. (2005), Seliksa Mordvas (PDF) (in Russian), Saransk: Republic of Mordovia Government Research Institute of Humanities

- Akhmetyanov, Rifkat (1981). Common Spiritual Culture Vocabulary Of Middle Volga Peoples (in Russian). Nauka.

- Setälä, Eemil; Smirnov, Ivan (1898). East Finns. Ivan Smirnov's Historical And Ethnographical Essays (in Russian). Sankt Peterburg: Yeltsin President Library.

- Melnikov, Pavel (1879). In The Mountains (in Russian).

- Stetsyuk, Valentin (2022). "Ancient Greeks And Italics In Ukraine And Russia".

- Fyodorova, Marina (1976). Slavs, Mordvins And Antes (in Russian). Voronezhg: Voronezh University Publishing.

- Palchan Israel (2018). The Khazar story: The Tail of Two Languages: Russian Hebrew and the Khazar story. ISBN 978-978-965-908-1. Retrieved 2022-04-16.

- Belinsky, Vladimir (2007). Moxel Country (in Russian). Smolensk: Posokh. ISBN 978-966-7601-91-1.

- Mierow, Charles Christopher, ed. (1915), The Gothic History of Jordanes, Princeton, Univ. Press

- Minorsky, Vladimir (1952), The Alān Capital *Magas and the Mongol Campaign, Cambridge University Press, JSTOR 608675

- Minorsky, Vladimir; al-ʿĀlam, Ḥudūd (1952), Ḥudūd al-ʿĀlam. The regions of the world: a Persian geography, 372 A.H./982 A.D para 52. The Alān Capital *Magas and the Mongol Campaign, Cambridge University Press

- Fournet, Arnaud (2008), Le vocabulaire Mordve de Witsen. Une forme ancienne du dialecte Zubu-Mokša. Études finno-ougriennes, tome 40

- Beekes, R.S.P.; Beekfirst2=L.V. (2010). Etymological Dictionary of Greek. Vols. 1 & 2.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- In Russian

- Аитов Г. Новый алфавит – великая революция на Востоке. К межрайонным и краевой конференции по вопросам нового алфавита. — Саратов: Нижневолжское краевое издательство, 1932.

- Ермушкин Г. И. Ареальные исследования по восточным финно-угорским языкам = Areal research in East Fenno-Ugric languages. — М., 1984.

- Поляков О. Е. Учимся говорить по-мокшански. — Саранск: Мордовское книжное издательство, 1995.

- Феоктистов А. П. Мордовские языки // Языки народов СССР. — Т.3: Финно-угроские и самодийские языки — М., 1966. — С. 172–220.

- Феоктистов А. П. Мордовские языки // Основы финно-угорского языкознания. — М., 1975. — С. 248–345.

- Феоктистов А. П. Мордовские языки // Языки мира: уральские языки. — М., 1993. — С. 174–208.

- Cherapkin, Iosif (1933). Moksha-Mordvin - Russian Dictionary. Саранск.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Vershinin, Valery (2009). Mordvinic (Erzya and Moksha languages) Etymological Dictionary (in Russian). Vol. 4. Yoshkar Ola.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Vershinin, Valery (2005). Mordvinic (Erzya and Moksha languages) Etymological Dictionary (in Russian). Vol. 3. Yoshkar Ola.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- In Moksha

- Девяткина, Татьяна (2002). Мокшэрзянь мифологиясь [Tatyana Devyatkina. Moksha-Erzya mythology] (in Moksha). Tartu: University of Tartu. ISBN 9985-867-24-6.

- Alyoshkin A. (1988). "Siyan Karks [Silver Belt]". Moksha (in Moksha). 6.

Footnotes

[edit]External links

[edit] Media related to Moksha language at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Moksha language at Wikimedia Commons

- Mokshen Pravda newspaper

- Moksha – Finnish/English dictionary (robust finite-state, open-source)

- Periodicals, textbooks and manuscripts in Moksha language in National Library of Finland

Moksha language

View on GrokipediaMoksha (Mokšen' kel') is a Mordvinic language of the Uralic family, spoken mainly by the Moksha people in the western Republic of Mordovia and surrounding regions of Russia.[1][2] With around 150,000 native speakers, primarily adults, the language faces endangerment as younger generations increasingly shift to Russian, limiting its transmission.[1][3] Moksha employs a Cyrillic orthography, reformed in the late 20th century, and developed a distinct literary standard in the 1920s separate from its close relative Erzya, despite partial mutual intelligibility between the two.[2][1] As a co-official language in Mordovia alongside Russian, it appears in education, media, and signage, though proficiency has declined amid broader linguistic assimilation trends in Russia.[2][1] Defining characteristics include agglutinative morphology and vowel harmony, hallmarks of Uralic languages, supporting a rich oral and written tradition among Moksha communities.[1]

Classification and relations

Linguistic affiliation

The Moksha language belongs to the Mordvinic branch of the Uralic language family.[4] Together with Erzya, it constitutes the Mordvinic languages, which were historically classified as dialects of a single Mordvin language but are now recognized as distinct, though closely related, languages with limited mutual intelligibility.[1] The Mordvinic subgroup is positioned within the Volga-Finnic or Mordvinic division of the Finno-Ugric languages, a major branch of the Uralic phylum that encompasses approximately 40 living languages spoken across northern Eurasia, from Scandinavia to Siberia.[5] This affiliation is supported by comparative linguistics, including shared phonological features such as vowel harmony and agglutinative morphology, as well as lexical cognates traceable to Proto-Uralic roots.[6] Moksha's closest relatives within Mordvinic are certain Erzya dialects, particularly Shoksha, exhibiting higher lexical similarity than with standard Erzya varieties.[4] The Uralic family's internal structure places Mordvinic alongside Mari and Permic languages in the eastern Finno-Ugric continuum, distinct from the western Finnic branch represented by Finnish and Estonian.[5]

Comparison with Erzya and other Mordvinic languages

Moksha and Erzya constitute the primary branches of the Mordvinic languages within the Finno-Ugric family, diverging sufficiently to render them not mutually intelligible, with Russian often serving as an interlingual medium among speakers.[7][8] Lexical overlap between the two, excluding 20th-century loanwords, falls below 50%, underscoring substantial divergence in core vocabulary.[9] Differences manifest across phonology, morphology, lexicon, and syntax, though both retain agglutinative structures typical of Uralic languages, including extensive case systems and vowel harmony.[8] Phonologically, Moksha preserves a distinction between the vowels /ɛ/ and /e/, whereas Erzya has merged them into a single /e/.[10] In unstressed syllables, Erzya exhibits pronounced vowel reduction, contrasting with Moksha's relative stability.[10] Moksha features a fuller set of eight vowels, including long and short variants, while Erzya shows more palatalization in consonants and distinct stress patterns tied to vowel quality.[11] External influences contribute: Moksha bears stronger Turkic substrate effects, evident in certain consonant clusters and loan integrations, compared to Erzya's heavier Russian overlay from prolonged northern exposure.[1] Grammatically, both languages employ nominative-accusative alignment with 12-15 cases, but Moksha diverges in possessive constructions and verb conjugation paradigms, featuring unique converb forms absent or altered in Erzya.[8] Clause constituent order in Moksha favors subject-object-verb more rigidly than Erzya's flexible SOV/SVO variations, as evidenced by distributional analyses of main constituents.[12] Lexically, Moksha retains more archaic Finno-Ugric roots alongside Turkic borrowings (e.g., for agriculture and administration), while Erzya incorporates Russian terms for modern concepts, amplifying divergence.[1] Beyond Erzya, other Mordvinic varieties are largely dialectal extensions rather than distinct languages; Shoksha, for instance, represents a transitional Moksha dialect with Erzya-like traits in eastern Mordovia, but lacks independent status due to high intelligibility with standard Moksha.[8] Extinct forms like Muroma show proto-Mordvinic affinities but offer limited comparative data, primarily through toponyms and substrate influences.[13] Overall, Moksha's western orientation fosters conservatism in phonology relative to Erzya's innovative reductions, reflecting geographic and contact histories.[10]Historical development

Origins and early records

The Moksha language descends from Proto-Mordvinic, the common ancestor of the Mordvinic branch within the Finno-Ugric languages of the Uralic family. The disintegration of Late Proto-Mordvin into Erzya and Moksha dialects occurred approximately during the first millennium CE, with Moksha developing in the western and southern regions of the historical Mordvin territory, influenced by geographic separation and early interactions with neighboring Turkic and Iranian groups.[14] This divergence is inferred from comparative linguistic reconstruction, including shared innovations in phonology and morphology, such as Moksha's retention of distinctions in mid vowels (/ɛ/ vs. /e/) absent in Erzya, alongside evidence of substrate influences from pre-Mordvinic populations in the Volga region.[13] Historical records of Moksha prior to the modern era are extremely limited, as the language remained primarily oral, lacking an indigenous writing system amid the Finno-Ugric peoples' pre-Christian traditions. The earliest attestations consist of isolated words and phrases documented by Russian and European scholars in the 18th century, often for ethnographic or missionary purposes, using adaptations of the Cyrillic alphabet.[2] These fragmentary records, including lexical lists compiled by figures such as Philip Johann von Strahlenberg, reflect initial efforts to transcribe Moksha phonology but do not constitute connected texts.[11] The first substantial written works in Moksha emerged in the mid-19th century, driven by Orthodox missionary activities under the Il'minskii system, which aimed to promote literacy in native languages for religious instruction. A catechism, prepared by missionary scholars, was published in 1861 as the inaugural printed book, marking the onset of a rudimentary literary tradition.[1] Earlier manuscript attempts, such as religious primers from the late 18th century, exist but were not widely disseminated until folk song collections and grammars appeared in the 1890s, providing the first glimpses of Moksha's poetic and vernacular forms. No pre-18th-century inscriptions or texts in Moksha have been identified, underscoring the language's late entry into written documentation compared to Indo-European neighbors.[2]Standardization and Soviet-era policies

Standardization efforts for the Moksha language began in earnest during the early Soviet period, aligning with the korenizatsiya policy that promoted the development of written forms for minority languages to foster literacy and cultural autonomy. The first Moksha primer appeared in 1924 using the Cyrillic alphabet, following an earlier Erzya primer in 1921, though the Moksha version was critiqued for inadequacies in coverage and orthographic consistency.[15] Between 1924 and 1927, additional letters—either digraphs or diacritic-modified characters—were incorporated into the Cyrillic script to better represent Moksha phonemes.[2] A brief experiment with Latinization occurred in 1932, when a Latin-based alphabet was officially approved for Moksha, reflecting broader Soviet initiatives to unify non-Slavic scripts under a Latin model for ideological alignment with international proletarian movements. However, this script was never widely adopted and saw limited practical use.[2] Conferences in 1928 and 1935 established the northwest dialect as the basis for the literary standard, prioritizing it for its relative uniformity and speaker base. By 1933, an official standardized written language was codified, firmly based on the Cyrillic alphabet, which had been in use since the 18th century but now received systematic orthographic rules akin to Russian conventions for loanwords and proper names.[5][2] Soviet language policy shifted dramatically in the late 1930s amid Stalinist purges and collectivization, targeting Moksha intellectuals and suppressing native-language publishing and education beyond rudimentary levels. This repression relegated Moksha to informal domains, with public life, media, and schooling increasingly dominated by Russian from the 1950s onward, limiting its instruction to the first grades in rural areas.[5] Soviet planners had initially sought a single codified norm for each ethnic language to support socialist modernization, but enforcement favored Russification, contributing to a decline in Moksha literary output and institutional support by the mid-20th century.[15]External linguistic influences

The Moksha language, as part of the Mordvinic branch of Uralic languages, exhibits substrate influences from Baltic languages, with loanwords documented since the 19th century, including terms for cultural and environmental concepts adapted into Moksha phonology and morphology.[16] These borrowings reflect prehistoric contacts in the Volga region, where Baltic-speaking groups interacted with proto-Mordvinic speakers prior to the 1st millennium CE.[16] Turkic languages, particularly Volga Bulgar and later Tatar, have contributed over 190 lexical items to Moksha vocabulary, often via intermediary Russian transmission, alongside non-lexical effects such as phonological adaptations in syllable structure and potential calques in nominal compounding.[17] These influences date to medieval interactions following the Mongol invasions of the 13th century, when Turkic nomads dominated the Middle Volga area, leading to integrations in domains like agriculture, administration, and trade; examples include Turkic-derived words for tools and governance retained in Moksha dialects.[17] Russian, as the dominant contact language since the 16th-century Muscovite expansion into Mordovia, exerts the most pervasive modern influence, shifting underlying word order from SOV to SVO in contemporary usage and introducing systematic consonant palatalization before front vowels, absent in core Uralic patterns.[18] This is evidenced in widespread Russian loanwords comprising up to 20-30% of Moksha lexicon in urban speakers, particularly numerals (e.g., Russian dva influencing Moksha counting in bilingual contexts) and administrative terms, accelerated by Soviet Russification policies from the 1920s onward that promoted code-switching and lexical borrowing.[18][19] Phonologically, Russian borrowings introduce mid vowels /e, o/ into non-initial syllables, contrasting with native Moksha restrictions.[11]Geographic and dialectal variation

Speaker distribution and demographics

The Moksha language is primarily spoken in the western and southern districts of the Republic of Mordovia, Russia, where ethnic Moksha communities form a significant portion of the population, as well as in adjacent regions including Penza Oblast, Saratov Oblast, Ryazan Oblast, and Nizhny Novgorod Oblast. Smaller communities exist in urban areas such as Saransk, the republic's capital, and scattered settlements across the Volga River basin. Outside Russia, negligible numbers of speakers are found among Mordvin diaspora in Kazakhstan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan, though these groups are predominantly Erzya-speaking. Moksha constitutes the majority language in certain rural western Mordovian locales but is a minority overall within the republic's Mordvinic-speaking population, with only about one-third of speakers residing there.[5] Estimates place the number of native Moksha speakers at approximately 150,000, mainly ethnic Moksha individuals who represent roughly one-third of the broader Mordvin ethnic group. According to the 2021 Russian census, the total Mordvin population stood at 484,450, of whom 52% reported proficiency in a Mordvinic language (Erzya or Moksha), indicating around 252,000 combined speakers amid ongoing decline. Moksha speaker numbers have decreased due to urbanization, intermarriage, and generational language shift toward Russian, with the language classified as endangered and limited transmission to youth. Rural elderly demographics predominate among fluent speakers, while urban and younger cohorts exhibit high bilingualism and reduced daily use.[20][21]Major dialects and subdialects

The Moksha language features distinct dialectal variation, primarily classified into three main groups: Central (M-I), Western (M-II), and South-Eastern (M-III). These groups reflect geographic and phonetic differences within the core speech area in western Mordovia and surrounding regions. The Central dialect forms the foundation of the standard literary language, characterized by features such as preservation of certain vowel qualities and serving as a reference for standardization efforts since the Soviet era.[8] Western dialects, including the Zubu subdialect, are spoken in the western parts of Mordovia and exhibit innovations in prosody and vowel reduction, such as frequent reduction of unstressed /u/ and /i/ in initial syllables compared to other groups. South-Eastern dialects, also known as Insar dialects, demonstrate unique accentuation patterns and phonetic originality, including differences in stress placement and vowel harmony application that distinguish them from Central varieties. These dialects are predominantly found in the Insar Valley and southeastern extensions.[8][22][23] Beyond the core triad, Moksha varieties include intermediate dialects bridging the main groups and mixed forms outside Mordovia, encompassing northern, southern, south-eastern, and eastern subgroups. These peripheral dialects often show hybridization with Erzya influences or substrate effects from neighboring languages, contributing to lexical and morphological diversity, such as variations in indefinite declension patterns. South-Western dialects, for instance, display accelerated vowel shifts in unstressed positions. Overall, dialect boundaries are fluid, with subdialectal features mapped through linguo-geographic studies revealing gradual transitions rather than sharp divides.[8][24][23]Phonological features

Vowels and vowel harmony

The Moksha language features a vowel system comprising seven phonemes: /i/, /e/, /æ/, /u/, /o/, /ɑ/, and the reduced /ə/.[8] [23] The phoneme /æ/ represents a front low vowel, primarily phonemic in central and certain western dialects, while /ɑ/ is the back low counterpart; /ə/ predominates in unstressed syllables and exhibits back (/ə̠/) and front (/ə̟/) allophones conditioned by preceding consonants or vowels.[8] High vowels like /i/ show velar allophones (/i̠/) in non-initial syllables following non-palatalized alveolars.[8] Unstressed vowels undergo centralization, often reducing toward schwa, with mid vowels (/e/, /o/) largely confined to stressed initial syllables and high vowels (/i/, /u/) restricted in non-initial unstressed positions.[23]| Vowel | Front | Central | Back |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i | u | |

| Mid | e | o | |

| Low | æ | ɑ, ə |

Consonants and phonological processes

The Moksha consonant system includes 33 phonemes, distinguished primarily by voicing opposition, palatalization contrast, and a variety of manners of articulation across labial, dental-alveolar, post-alveolar, palatal, and velar places.[23] Palatalization affects most obstruents and sonorants, creating pairs such as /t/ vs. /tʲ/ and /l/ vs. /lʲ/, while velars lack palatalized counterparts.[23] Voiceless sonorants like /r̥/ and /l̥/ occur, particularly in intervocalic positions or before voiceless obstruents, and the velar fricative /x/ appears mainly in loanwords.[25] Affricates such as /t͡ʃ/, /d͡ʒ/, /t͡s/, and /d͡z/ further enrich the inventory, with palatalized variants for some.[26]| Place/Manner | Bilabial | Labiodental | Dental-Alveolar | Palatalized Alveolar | Post-Alveolar | Palatal | Velar |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops | p, b | t, d | tʲ, dʲ | k, g | |||

| Fricatives | f, v | s, z | sʲ, zʲ | ʃ, ʒ | x | ||

| Affricates | t͡s, d͡z | t͡sʲ, d͡zʲ | t͡ʃ, d͡ʒ | t͡ɕ, d͡ʑ | |||

| Nasals | m | n | nʲ | ɲ | ŋ | ||

| Laterals | l, l̥ | lʲ, l̥ʲ | |||||

| Rhotics | r, r̥ | rʲ, r̥ʲ | |||||

| Glides | j |

Stress and prosody

In Moksha, primary word stress typically falls on the first syllable, occurring in approximately 89% of tokens across analyzed speech data from central dialects.[23] Exceptions arise when the initial syllable contains a high (narrow) vowel such as /i/ or /u/, in which case stress shifts to the following syllable if it holds a low (broad) vowel like /a/ or /ä/, reflecting a preference for stressing full vowels over reduced ones.[23] [8] This pattern exhibits dialectal and idiolectal variation, with stress described as relatively free compared to fixed systems in many Uralic languages, though morphological factors like derivation or compounding can influence placement.[23] Acoustic correlates of stress include increased vowel duration in stressed syllables, averaging 160 ms compared to 140 ms in unstressed ones in disyllabic words, alongside greater formant stability and resistance to centralization.[23] Unstressed vowels often reduce to schwa [ə], particularly in non-initial positions, contributing to a prosodic structure that favors trochaic (disyllabic) feet.[23] Secondary stresses may appear on odd-numbered syllables in longer words, supporting rhythmic alternation, while fundamental frequency (F0) rises at stressed syllable onsets but primarily aligns with phrasal intonation rather than marking word-level prominence.[23] Phrasal prosody in Moksha features rising F0 contours in phrase-final positions and falling ones in sentence-final contexts, integrating word stress into broader intonational patterns.[23] Rhythm tends toward stress-timing influenced by syllable structure, with durations longer in open syllables and varying by stress position, as evidenced in empirical analyses of 1,664 tokens from eight speakers.[23] No phonemic tone or distinctive quantity contrasts lexical items, distinguishing Moksha prosody from related Erzya varieties where stress is more mobile.[23]Orthography and writing

Historical scripts and transition to Cyrillic

The Moksha language lacks evidence of pre-modern indigenous scripts, with the earliest written attestations appearing in the 18th century using adaptations of the Cyrillic alphabet for religious purposes, such as missionary translations and catechisms.[2] These initial efforts relied on the Russian Orthodox Cyrillic base, augmented sporadically to accommodate Moksha-specific sounds, though no standardized orthography existed until the 19th century. The first printed Moksha text, a catechism, was published in 1861, marking the onset of more consistent literary use within this script tradition.[1] In the 1920s, amid efforts to develop Mordvinic literary norms, the Moksha Cyrillic alphabet incorporated additional characters—such as digraphs and letters with diacritics—between 1924 and 1927 to better reflect phonological distinctions like vowel harmony and consonant clusters.[2] This period saw growing publication of Moksha materials, but Soviet nationalities policy soon introduced pressures for script reform. A Latin-based alphabet, proposed as early as 1930 and officially approved in 1932 by the Central Committee for New Alphabets, aimed to align with broader latinization campaigns for non-Slavic Soviet languages; it featured 32 letters tailored to Moksha phonemes, including digraphs for affricates and diacritics for vowels.[28] [2] The Latin script was briefly implemented for Moksha from 1932 to 1939, similar to Erzya, though with limited publications before reversion to Cyrillic. By 1939, standardization proceeded exclusively with Cyrillic, incorporating reforms to spelling and dialect base while retaining the expanded letter inventory from the 1920s; this Cyrillic system, based on the Russian model with Moksha-specific additions like Ӛ/ӛ and Ъ̈/ъ̈, has endured without further script shifts.[5] The failed Latin transition reflected pragmatic resistance to disruption in established Cyrillic literacy among Moksha speakers, many bilingual in Russian, prioritizing continuity over ideological experimentation.[2]Current orthographic conventions

The Moksha language employs the standard 33-letter Russian Cyrillic alphabet for its contemporary writing system, without unique additional characters. This orthography was formalized as part of the literary language standardization approved in 1933, building on earlier adaptations from the 1920s. Spelling conventions align closely with Russian orthographic principles to facilitate bilingualism and administrative use, particularly in the Republic of Mordovia where Moksha holds co-official status alongside Russian and Erzya.[5][29] Moksha's seven vowel phonemes—a front unrounded mid (/e/), front unrounded low (/æ/), back unrounded high central (/ɨ/), back rounded high (/u/), back rounded mid (/o/), back unrounded low (/ɑ/), and back unrounded central schwa (/ə/)—are represented by eleven graphemes: а, о, у, и, ы, э, е, ё, ю, я, ъ. Front vowels typically use е, ё, ю, я in palatal contexts, while back vowels employ а, о, у, э; the letters и and ы distinguish non-palatal high vowels, and ъ denotes the schwa. These mappings accommodate Moksha's vowel harmony and reduction patterns without digraphs or diacritics beyond standard Cyrillic.[30] Consonant representation follows Russian norms, with palatalization marked either by the soft sign (ь) after hard consonants or by selection of "soft" vowels (е, ё, ю, я, и). Moksha's 33 consonant phonemes, including affricates and fricatives like /t͡ɕ/ (written ч) and /ʃ/ (ш), use the full Russian inventory; letters щ and ъ appear primarily in Russian loanwords and proper names. Orthographic rules specify separate writing for postpositions (e.g., модать лангса "under the horse") and compound conjunctions (e.g., сяс мес "as if"), preserving morphological clarity.[30][2] A 1993 spelling reform refined these conventions to align more precisely with phonetic realizations in the central dialect basis of the literary standard, addressing inconsistencies from prior Soviet-era scripts while maintaining compatibility with Russian typography. These norms are codified in Republic of Mordovia government decree No. 422 of November 1, 2010, which endorses their use in official domains.[2]Grammatical structure

Nominal system and case marking

The nominal system of Moksha features agglutinative inflection for case, number, definiteness, and possession on nouns, with suffixes typically added sequentially. Nouns distinguish singular and plural forms, where singular often employs zero marking and plural uses suffixes such as -t or -tʲ in indefinite declension.[8] Possession is expressed via personal suffixes, such as -zʲæ for first-person singular on singular nouns, which may combine with case markers.[8] Moksha employs two primary declensions: indefinite and definite. The indefinite declension marks case alone and includes up to 13 or 15 cases depending on analytical traditions, such as nominative (subject and predicate nominative), genitive (-nʲ, for possession and certain objects), dative (-nʲdʲi, indirect objects), partitive (-dɑ or -tɑ, partial objects), inessive (-sɑ, static location inside), elative (-stɑ, motion from inside), illative (-s, motion to inside), lative (-v, -u, or -i, motion toward surface), prolative (-vɑ, -gɑ, -gæ, or -kɑ, motion along or through), ablative (motion from surface), comparative (-ʃkɑ, comparison), abessive (-ftəmɑ, absence or privation), translative (-ks, change of state), and causative (-nksɑ, cause).[8] [31] Plural forms in indefinite declension are limited primarily to nominative, with other cases resorting to definite-like forms.[8] The definite declension incorporates definiteness marking, often via fused suffixes derived from historical demonstratives, and is restricted in singular to nominative (-sʲ), genitive (-tʲ), and dative, while plural extends to additional cases built on indefinite bases plus definiteness affixes like -tʲnʲæ for nominative.[8] [32] Definiteness contrasts with indefiniteness semantically, affecting object marking and reference, though traditional grammars emphasize morphological over purely referential distinctions in genitive forms.[32] Adjectives and attributive modifiers precede nouns but do not agree in case, number, or definiteness under standard conditions, reflecting a head-final noun phrase structure without obligatory concord.[33] However, nominal ellipsis triggers concord on the nearest modifier for case and other features, revealing underlying agreement potential.[31] Postpositions govern specific cases, with inflection attaching to the noun rather than the postposition.[34]Verbal conjugation and tense-aspect

Moksha verbs inflect for person and number, distinguishing between subjective and objective paradigms. The subjective paradigm agrees solely with the subject and is used with indefinite objects or adverbial expressions of duration, typically conveying imperfective aspect. In contrast, the objective paradigm agrees with both subject and a definite (genitive) object, marking perfective aspect and exhibiting syncretism in certain person combinations due to paradigm structure constraints.[8][35] The tense-aspect system features three tenses integrated with aspectual distinctions. The present tense lacks an overt marker, relying on person suffixes appended to the stem, as in mor-ɑn ("I sing") for 1SG subjective. The first past tense employs stem palatalization followed by person suffixes like -nj (e.g., morɑ-nj "I sang"), while the second past or habitual past uses -lj (e.g., morɑ-lj "I used to sing" or pluperfect contexts). Aspectual nuances arise derivatively: iterative (frequentative) actions are formed with stem-internal morphemes such as -ənd-, -n’ə-, or -s’ə-, which precede tense markers to denote repetition or habituality (e.g., a verb like paz-ənd-ɑn "I jump repeatedly"). An avertive aspect, indicating narrowly avoided events, utilizes -əkšn’ə-, polysemous with one iterative variant but distinguished semantically.[8][36]| Person | Subjective Present Example (mor- "sing") | Objective Present Example (with 1SG object) |

|---|---|---|

| 1SG | mor-ɑn | (syncretic forms vary; e.g., -sɑmɑk for 2SG>1SG) |

| 2SG | mor-ɑt | mor-sɑmɑk |

| 3SG | morɑ- | morɑ-s |

| 1PL | mor-ɑmskə | mor-ɑmskəs |

Syntactic patterns and word order

Moksha syntax features flexible constituent order, enabled by rich case marking that signals grammatical relations independently of linear position. The predominant word order in transitive declarative clauses is subject-verb-object (SVO), which serves as the unmarked structure in narrative prose, though subject-object-verb (SOV) occurs frequently, comprising up to 48.5% of orders in dialogues and 59.3% in negative clauses based on corpus analysis of 1,706 clauses.[12][8] This flexibility reflects a partial shift from the Proto-Uralic SOV base under Russian contact influence, resulting in near-equal object-verb (OV) and verb-object (VO) frequencies in some datasets.[6] Several factors condition variations in word order. Polarity drives OV preference in negatives, while pronominal or indefinite objects often precede the verb (e.g., 40-43% preverbal in narration), and objective verb conjugation—triggering agreement with definite objects—favors postverbal placement in 82% of cases.[12] Noun phrases are typically head-final, with attributive modifiers preceding the noun, and postpositional phrases follow head-final patterns; relative clauses are externally headed but exhibit head-final tendencies or inverse case attraction in left-peripheral positions.[37][8] Differential object marking employs genitive for definite or perfective objects (eliciting objective conjugation) and nominative or partitive for indefinites, reinforcing pragmatic motivations like topicality over rigid syntax.[8] Clause embedding and non-finite constructions adhere to head-initial patterns for auxiliaries and modals, with infinitive complements following in most cases (90%), though objects may precede infinitives unlike in related Erzya.[12] Copular clauses place the copula after the subject and before complements in present tense, shifting postverbally in past with bound forms; existential and possessive structures maintain similar flexibility but prioritize information structure.[8] Overall, these patterns underscore Moksha's agglutinative profile, where morphological explicitness permits discourse-driven rearrangements without ambiguity.[37]Lexicon and etymology

Core vocabulary and Uralic roots

The core vocabulary of Moksha, encompassing pronouns, numerals, body parts, and terms for natural elements, largely preserves Proto-Uralic roots, reflecting the language's deep ties to the Uralic family. This stability in basic lexicon is a hallmark of Uralic languages, with Moksha retaining features such as vowel harmony in about 80% of its inherited words, a phonological trait traceable to the protolanguage.[8] Innovations in Mordvinic, including Moksha, involve dialectal shifts and partial vowel reductions, but core items resist replacement by borrowings.[4] Pronouns exemplify this inheritance: the first-person singular mon derives from Proto-Uralic minä, paralleling Finnish minä, while the second-person singular toń stems from tinä, akin to Finnish sinä. Numerals show similar continuity, as in vet́ə "five," cognate with Finnish viisi and Northern Saami vihtta from Proto-Uralic viüle. The word for "sun" or "day," ši, traces to Proto-Uralic kećä.[8][4] Body part terms further highlight Uralic affinities. Moksha käd́ "hand; arm" corresponds to Proto-Uralic käte and Finnish käsi; veŕ "blood" to wërä and Finnish veri; ked́ "skin" to Finnic kesi; and śeĺmə "eye" to śilmä, Finnish silmä, and Northern Saami čalbmi. Terms for fauna and phenomena, such as kargə "crane," align with Finnish kurki and Saami guorgga. These cognates, documented in etymological reconstructions, affirm Moksha's phonological and lexical evolution from a shared Uralic ancestor dated to approximately 7,000–10,000 years ago.[4]| English | Moksha | Finnish | Proto-Uralic (approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hand/arm | käd́ | käsi | *käte |

| Blood | veŕ | veri | *wërä |

| Eye | śeĺmə | silmä | *śilmä |

| Five | vet́ə | viisi | *viüle |

Borrowings from Russian and other languages

The Moksha language exhibits extensive lexical borrowing from Russian, reflecting centuries of close contact, bilingualism, and administrative dominance within the Russian Federation. Modern Moksha incorporates thousands of Russian loanwords, particularly in domains such as technology, administration, and everyday culture, with integration often preserving original phonology without substitution; for instance, Russian dača ('summer house') appears as dat͡ɕa. [11] [38] Other examples include staka ('hardness') from Russian staka and bok(a) ('side') from bok, demonstrating direct adaptation into Moksha morphology. [38] [17] This influx has accelerated since the 20th century, driven by urbanization and education in Russian, resulting in Russian-dominant bilingualism among speakers and ongoing lexical expansion without altering core Uralic roots. [11] Borrowings from Turkic languages form a significant historical layer in Moksha, exceeding those in the related Erzya dialect due to prolonged interactions in the Volga-Kama region during medieval periods of Bulgar and Tatar influence. Moksha lexicon shows Turkic elements in terms related to agriculture, trade, and kinship, with Persian-mediated loans also present via Turkic intermediaries, contributing to a richer substrate than in Erzya. [39] [38] These predate heavy Russification and illustrate adaptive phonological shifts, such as vowel harmony alignments, though specific inventories remain understudied compared to Russian loans. [17] An older stratum consists of Baltic loanwords, evidencing prehistoric contacts between Proto-Mordvinic speakers and Baltic tribes along migration routes, documented since 19th-century linguistic analysis. Examples include terms for cultural or environmental concepts, integrated deeply into basic vocabulary, with cognates traceable to Proto-Baltic forms; this layer predates Turkic and Russian influences and highlights early Indo-European-Uralic interactions without implying genetic affiliation. [16] [40] Such borrowings, numbering in the dozens, underscore Moksha's role as a recipient language in multi-ethnic Eurasian dynamics, though they constitute a minor proportion relative to Uralic etyma. [39]Sociolinguistic dynamics

Vitality and speaker trends

The Moksha language is spoken by an estimated 150,000 people, primarily ethnic Mokshas residing in the Republic of Mordovia and adjacent regions of Russia's Volga Federal District.[20] This figure reflects native proficiency data from linguistic surveys, though official Russian census reporting aggregates Mordvinic languages (Erzya and Moksha) without consistent separation, with total Mordvin language claimants numbering around 350,000–450,000 as of the 2010 census.[1] Vitality assessments classify Moksha as endangered, with intergenerational transmission weakening as younger speakers increasingly adopt Russian as their primary language in home and community settings.[3] Ethnologue notes that while adults in ethnic communities continue first-language use, not all youth do so, contributing to a vitality score indicating institutional and educational limitations.[3] UNESCO deems it "definitely endangered," citing risks from assimilation pressures and bilingualism favoring the dominant Russian language.[41] Historical trends show sharp declines in acquisition: between the early 1970s and late 1980s, the number of children enrolled in Mordvin-language schooling fell from 77,000 to 24,000, a pattern persisting amid post-Soviet policy shifts that have not reversed broader speaker erosion. Recent Russian censuses proxy further decline through ethnic self-identification, with Moksha-specific identifiers dropping to 11,801 in 2021 from higher prior benchmarks, amid overall Mordvin population reductions of nearly 35% since 2010.[5] Activists report even faster language loss than census data suggest, driven by urbanization, media dominance of Russian, and inconsistent native-language education in Mordovia.[42] Despite co-official status in Mordovia, daily use remains confined to rural elderly cohorts, with urban youth exhibiting passive bilingualism at best.[8]Language use in domains and bilingualism

Moksha speakers exhibit near-universal bilingualism with Russian, as virtually all proficient Moksha users are fluent in Russian, often acquired through formal education and daily interactions. This bilingualism is asymmetric, with Russian functioning as the high-prestige language in most public and institutional contexts, while Moksha occupies a subordinate role primarily in private and informal spheres.[6][43] In domestic and rural village settings, Moksha remains the primary medium for everyday communication, especially among elderly speakers in Mordovia's western regions. However, its use is declining, with younger generations showing reduced proficiency and limited transmission to children. Formal domains such as education, administration, commerce, and media are overwhelmingly Russian-dominated, where Moksha is rarely employed outside occasional cultural or heritage contexts. This pattern reflects a classic case of unequal diglossia, despite Moksha's designation as a state language alongside Russian and Erzya in the Republic of Mordovia's 1995 constitution and subsequent 1998 legislation regulating its application in state bodies.[6][33][44] Code-switching between Moksha and Russian is prevalent among bilingual speakers, manifesting in insertions of Russian nouns or verbs into Moksha sentences (accounting for approximately 54% of switches) and alternations at clause boundaries (46%). Such practices, observed in corpora from Mordovian villages collected between 2013 and 2016, indicate linguistic convergence influenced by Russian dominance. Proficiency surveys reveal that only about 40% of ethnic Moksha identify as speakers, with around 2,000 active users in select Mordovian communities of roughly 5,000 ethnic Moksha, underscoring the language's vulnerability in intergenerational use.[6]

Policy frameworks in Russia and Mordovia

The policy framework governing the Moksha language operates within Russia's federal structure, where the 1993 Constitution (Article 68) establishes Russian as the state language nationwide while permitting federal subjects like republics to designate additional official languages. The Federal Law "On Languages of the Peoples of the Russian Federation" (No. 1801-1, adopted April 25, 1991, with subsequent amendments) mandates the preservation, development, and use of minority languages in designated territories, including Mordvinic languages such as Moksha, through measures like education, media, and administrative support. However, 2018 amendments to federal education legislation (Federal Law No. 273-FZ) shifted native language instruction from compulsory to elective status in non-mother-tongue schools, reducing mandatory hours and prioritizing Russian proficiency, which has impacted Moksha's institutional presence.[45] In the Republic of Mordovia, the 1995 Constitution explicitly recognizes Russian, Erzya, and Moksha as co-official state languages, requiring their equivalence in public administration, judicial proceedings, and cultural activities. This trilingual status is reinforced by republican legislation, including Law No. 19-3 of 1998, which outlines Moksha's application in state institutions, documentation, and services, aiming to ensure parity with Russian in official domains. Educational policies mandate Moksha instruction in primary and secondary schools within Moksha-speaking districts, with state-funded programs for teacher training and curriculum development, though enrollment has declined due to voluntary opt-outs and Russian-dominant bilingualism.[5][46][47] Implementation challenges persist, as Russian remains the dominant language of instruction and governance, with Moksha often relegated to supplementary roles; for instance, while dictation events and cultural initiatives by the Ministry of Culture promote literacy, systemic assimilation pressures and underfunding limit vitality. Critics, including ethnic advocacy groups, argue that federal centralization erodes republican autonomy, favoring a unified "Mordvin" identity over distinct Moksha recognition, though official frameworks maintain separate standardization for Erzya and Moksha orthographies and lexicons.[48][49]Cultural and institutional roles

Literature and literary figures

Moksha literature developed primarily during the Soviet period, with written works emerging after the 1917 Revolution amid literacy campaigns and orthographic standardization efforts that transitioned from Latin to Cyrillic scripts in the 1930s. Early publications focused on poetry depicting rural life, collectivization, and social transformation, often aligned with socialist realism. Folklore traditions, including epic songs and riddles, provided foundational oral elements, but original prose and drama gained prominence only post-1920s.[50][51] Prominent early poets included Maksim Afanas'evich Byabin (also known as Baban), who began publishing verse in the late 1920s and contributed to anthologies such as Vaseny askolks (1932), featuring poems on themes like tractor drivers and village hardships. Byabin, a teacher by training, documented Mikhail Bakhtin's 1937 lectures on Shakespeare in Saransk, reflecting his engagement with broader literary discourse. Grigory Il'ich Elmeev (1906–1941) debuted in 1932 with poetry emphasizing labor and nature, though his career was curtailed by wartime conditions. Fedor Durnov also rose in the 1930s, contributing to the nascent poetic canon amid purges that affected many Mordvin writers.[52][53] Post-World War II figures expanded prose and drama. Fyodor Semenovich Atyanin (1910–1975), a Union of Writers member and honored cultural worker, produced novels and stories on wartime and postwar themes. Ilya Maksimovich Devin (born 1922) authored works exploring ethnic identity and daily struggles. In drama, Grigory Pinyasov gained recognition for Mekoltses' Karguzhsta ("The Last of the Kargushas"), addressing historical clan leaders. Later writers like Anatoly Tyapaev depicted mid-20th-century village life in novellas such as Izvilistymi tropami ("Winding Paths"). Despite institutional support through Mordovian publishing houses, production remains limited, with ongoing challenges in distribution and readership amid Russian dominance.[54][55]Media, education, and transmission efforts

Moksha-language media in the Republic of Mordovia encompasses print, radio, and television outlets, though usage remains limited amid Russian dominance. Newspapers such as Mokshen Pravda publish regularly in Moksha, with four such titles reported as of 2019.[47][56] Radio broadcasts, including programs on stations like Vaygel, feature Moksha content often interspersed with Russian code-switching, focusing primarily on cultural and literary topics rather than daily life issues. Television programming in Moksha exists but garners low viewership, attributed to speakers' insufficient language proficiency and disinterest in available content.[57] In education, Moksha serves mainly as a subject in primary grades within Mordovian schools, with its role as a medium of instruction having declined since the late 1950s due to Russification policies.[5] Pre-1990s data indicate around 200 schools used Moksha or Erzya for instruction and 275 for subject teaching, but reforms shifted emphasis toward Russian. Revitalization initiatives from the late 1990s onward, including Mordovia's 1995 constitution designating Moksha as a state language alongside Russian and Erzya, have aimed to expand its curricular presence.[58] In December 2021, three pilot classes in Saransk introduced multilingual instruction using Moksha, Russian, and English, as part of broader efforts to integrate minority languages into schooling.[59] Transmission efforts focus on policy-driven promotion and community events to sustain intergenerational use, countering assimilation trends. State programs since the 1990s have supported electronic media development in Moksha to enhance accessibility.[59] Annual open dictations in Moksha, organized by Mordovia's Ministry of Culture, test and encourage literacy among participants, with results publicized to foster public engagement.[48] Despite these measures, surveys indicate persistent challenges, including low media consumption due to language attrition and preference for Russian sources.[60]Debates and challenges

Revitalization initiatives and outcomes

![Trilingual street sign in Saransk showing multilingual policy efforts][float-right] The Republic of Mordovia has implemented various policies to support Moksha language use since the late 1990s, including its designation as one of three official languages alongside Russian and Erzya in the republic's constitution, which mandates governmental measures for its development and preservation.[61] A national program for the preservation and promotion of Mordvin languages, encompassing Moksha, was adopted around 2020, focusing on cultural support and reliable implementation mechanisms.[62] Educational initiatives include the continuation of Moksha as a language of instruction in some rural schools and the launch of three pilot classes using Moksha and Erzya as primary instructional languages in 2021, aimed at enhancing immersion and transmission to younger generations.[63][59] Media and cultural efforts form another pillar, with programs on national television broadcasting in Moksha and Erzya as of 2020, alongside the promotion of electronic media content in these languages to expand digital presence.[64] Cultural activities, such as annual open dictations in Moksha conducted by the Ministry of Culture, seek to foster literacy and public engagement, with results publicized to gauge proficiency levels.[48] Despite these measures, revitalization outcomes remain limited, as evidenced by persistent declines in speaker numbers; census data indicate a sharp drop in self-reported Mordvin language proficiency from 614,260 in 2002 to 392,941 in 2010, reflecting broader assimilation trends where Russian dominates daily and institutional domains. Evaluations of Finno-Ugric republic policies, including Mordovia's, highlight implementation gaps, such as insufficient executive programs for language laws and inadequate expansion into urban education and administration, constraining reversal of endangerment.[65] Russian's pervasive role in urbanization and intergenerational transmission continues to erode Moksha vitality, underscoring the challenges of policy efficacy amid centralized Russification pressures.Assimilation pressures and policy critiques