Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nefertiti

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Neferneferuaten-Nefertiti in hieroglyphs | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Neferneferuaten Nefertiti Nfr nfrw itn Nfr.t jy.tj Beautiful are the Beauties of Aten, the Beautiful one has come | ||||||||||||||

Nefertiti (/ˌnɛfərˈtiːti/;[3] c. 1370 – c. 1330 BC) was a queen of the 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, the great royal wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten. Nefertiti and her husband were known for their radical overhaul of state religious policy, in which they promoted an exclusivist and possibly even monotheistic religion, Atenism, centered on the sun disc and its direct connection to the royal household. With her husband, she reigned at what was arguably the wealthiest period of ancient Egyptian history.[4]

After her husband's death, some scholars believe that Nefertiti ruled briefly as the female pharaoh known by the throne name Neferneferuaten just before the ascension of Tutankhamun, although this identification is a matter of ongoing debate.[5][6] If Nefertiti did rule as pharaoh, her reign was marked by the fall of Amarna and the relocation of the capital back to the traditional city of Memphis after her death.[7]

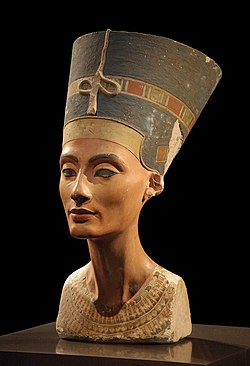

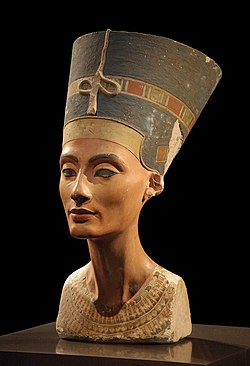

In the 20th century, Nefertiti was made famous by the discovery and display of her ancient bust, now in Berlin's Neues Museum. The bust is one of the most copied works of the art of ancient Egypt. It is attributed to the Egyptian sculptor Thutmose, and was excavated from his buried studio complex in the early 20th century.[8]

Names and titles

[edit]Nefertiti had many titles, including:

- Neferneferuaten[9] (Beautiful is the beauty of Aten) nfr-nfrw-jtn

- Hereditary Princess (iryt-p`t)

- Great of Praises (wrt-Hzwt)

- Lady of Grace (nebet-imat, nbt-jmꜣt)

- Sweet of Love (beneret-merut, bnrt-mrwt)

- Lady of The Two Lands (nebet-tawi, nbt-tꜣwj)

- Main King's Wife, his beloved (hemet-nesut-aat meretef, ḥmt-nswt-ꜥꜣt mrt.f)

- Great King's Wife, his beloved (hemet-nesut-weret meretef, ḥmt-nswt-wrt mrt.f)

- Lady of All Women (henut-hemut-nebut, ḥnwt-ḥmwt-nbwt)

- Mistress of Upper & Lower Egypt (henut-shemau-mehu, ḥnwt-šmꜣw-mḥw).[10]

While modern Egyptological pronunciation renders her name as Nefertiti, her name was the sentence nfr.t jj.tj (or Nfr.t-jy.tj[11]), meaning "the beautiful one has come", and probably contemporarily pronounced Naftita from older Nafrat-ita or perhaps Nafert-yiti.[12][13]

Family and early life

[edit]Almost nothing is known about Nefertiti's life before her marriage to Akhenaten. Scenes from the tombs of the nobles in Amarna mention that Nefertiti had a sister, named Mutbenret.[14][15][16] Further, a woman named Tey carried the title of "Nurse of the Great Royal Wife."[17] In addition, Tey's husband Ay carried the title "God's Father." Some Egyptologists believe that this title was used for a man whose daughter married the pharaoh.[18] Based on these titles, it has been proposed that Ay was in fact Nefertiti's father.[11] However, neither Ay nor Tey are explicitly referred to as Nefertiti's parents in the existing sources. At the same time, no sources exist that directly contradict Ay's fatherhood which is considered likely due to the great influence he wielded during Nefertiti's life and after her death.[11] According to another theory, Nefertiti was the daughter of Ay and a woman besides Tey, but Ay's first wife died before Nefertiti's rise to the position of queen, whereupon Ay married Tey, making her Nefertiti's stepmother. Nevertheless, this entire proposal is based on speculation and conjecture.[19]

It has also been proposed that Nefertiti was Akhenaten's full sister, though this is contradicted by her titles which do not include the title of "King's Daughter" or "King's Sister," usually used to indicate a relative of a pharaoh.[11] Another theory about her parentage that gained some support identified Nefertiti with the Mitanni princess Tadukhipa,[20] partially based on Nefertiti's name ("The Beautiful Woman has Come") which has been interpreted by some scholars as signifying a foreign origin.[11] However, Tadukhipa was already married to Akhenaten's father and there is no evidence for any reason why this woman would need to alter her name in a proposed marriage to Akhenaten, nor any hard evidence of a foreign non-Egyptian background for Nefertiti.

The exact dates when Nefertiti married Akhenaten and became the king's great royal wife are uncertain. They are known to have had at least six daughters together, including Meritaten, Meketaten, Ankhesenpaaten (later called Ankhesenamun when she married Tutankhamun), Neferneferuaten Tasherit, Neferneferure, and Setepenre.[16][20] She was once considered as a candidate for the mother of Tutankhamun, however a genetic study conducted on discovered mummies suggests that she was not.[21]

Life

[edit]Nefertiti first appears in scenes in Thebes. In the damaged tomb (TT188) of the royal butler Parennefer, the new king Amenhotep IV is accompanied by a royal woman, and this lady is thought to be an early depiction of Nefertiti. The king and queen are shown worshiping the Aten. In the tomb of the vizier Ramose, Nefertiti is shown standing behind Amenhotep IV in the Window of Appearance during the reward ceremony for the vizier.[20]

During the early years in Thebes, Akhenaten (still known as Amenhotep IV) had several temples erected at Karnak. One of the structures, the Mansion of the Benben (hwt-ben-ben), was dedicated to Nefertiti. She is depicted with her daughter Meritaten and in some scenes the princess Meketaten participates as well. From all the scenes preserved on talatat that can be dated to the first five years of Akhenaten’s reign, Nefertiti is depicted almost twice as frequently as her husband, indicating her exceptionally high visibility during this period and demonstrating her political importance. She is shown appearing behind her husband the pharaoh in offering scenes in the role of the queen supporting her husband, but she is also depicted in scenes that would have normally been the prerogative of the king. She is shown smiting the enemy, and captive enemies decorate her throne.[22]

In the fourth year of his reign, Amenhotep IV decided to move the capital to Akhetaten (modern Amarna). In his fifth year, Amenhotep IV officially changed his name to Akhenaten, and Nefertiti was henceforth known as Neferneferuaten-Nefertiti. The name change was a sign of the ever-increasing importance of the cult of the Aten. It changed Egypt's religion from a polytheistic religion to a religion which may have been better described as a monolatry (the depiction of a single god as an object for worship) or henotheism (one god, who is not the only god).[23]

The boundary stelae of years 4 and 5 mark the boundaries of the new city and suggest that the move to the new city of Akhetaten occurred around that time. The new city contained several large open-air temples dedicated to the Aten. Nefertiti and her family would have resided in the Great Royal Palace in the centre of the city and possibly at the Northern Palace as well. Nefertiti and the rest of the royal family feature prominently in the scenes at the palaces and in the tombs of the nobles. Nefertiti's steward during this time was an official named Meryre II. He would have been in charge of running her household.[5][20]

Inscriptions in the tombs of Huya and Meryre II dated to Year 12, 2nd month of Peret, Day 8 show a large foreign tribute. The people of Kharu (the north) and Kush (the south) are shown bringing gifts of gold and precious items to Akhenaten and Nefertiti. In the tomb of Meryre II, Nefertiti's steward, the royal couple is shown seated in a kiosk with their six daughters in attendance.[5][20] This is one of the last times princess Meketaten is shown alive.

Two representations of Nefertiti that were excavated by Flinders Petrie appear to show Nefertiti in the middle to later part of Akhenaten's reign 'after the exaggerated style of the early years had relaxed somewhat'.[24] One is a small piece on limestone and is a preliminary sketch of Nefertiti wearing her distinctive tall crown with carving begun around the mouth, chin, ear and tab of the crown. Another is a small inlay head (Petrie Museum Number UC103) modeled from reddish-brown quartzite that was clearly intended to fit into a larger composition.

Meketaten may have died in year 13 or 14. Nefertiti, Akhenaten, and three princesses are shown mourning her.[25] The last dated inscription naming Nefertiti and Akhenaten comes from a building inscription in the limestone quarry at Deir Abu Hinnis. It dates to year 16 of the king's reign and is also the last dated inscription naming the king.[26] Akhenaten is known to have died in his 17th year at Amarna.[27][28]

Possible reign as a Pharaoh

[edit]

Many scholars believe Nefertiti had a role elevated from that of great royal wife, and was promoted to co-regent by her husband Pharaoh Akhenaten before his death.[29] She is depicted in many archaeological sites as equal in stature to a King, smiting Egypt's enemies, riding a chariot, and worshipping the Aten in the manner of a pharaoh.[30] When Nefertiti's name disappears from historical records, it is replaced by that of a co-regent named Neferneferuaten, who became a female Pharaoh.[31] It seems likely that Nefertiti, in a similar fashion to the previous female Pharaoh Hatshepsut, assumed the kingship under the name Pharaoh Neferneferuaten after her husband's death. She was then succeeded by Tutankhamun.[26]

It seems less possible that Nefertiti disguised herself as a male and assumed the male alter ego of Smenkhkare. According to Van Der Perre, Smenkhkare is thought to be a co-regent of Akhenaten who died before Neferneferuaten assumed the kingship.[26]

If Nefertiti did rule Egypt as a Pharaoh, it has been theorized that she would have attempted damage control and may have re-instated the ancient Egyptian religion and the Amun priests. She would have raised Tutankhamun in the worship of the traditional gods.[32]

Archaeologist and Egyptologist Dr. Zahi Hawass theorized that Nefertiti returned to Thebes from Amarna to rule as a Pharaoh, based on ushabti and other feminine evidence of a female pharaoh found in Tutankhamun's tomb, as well as evidence of Nefertiti smiting Egypt's enemies which was a duty reserved to kings.[33]

Old theories about Nefertiti's career

[edit]

Pre-2012 Egyptological theories assumed that Nefertiti vanished from the historical record around Year 12 of Akhenaten's reign, with no word of her existence thereafter. The conjectured causes of her death and disappearance included injury, a plague that was sweeping through the city, and a natural cause. This theory was based on the discovery of several ushabti fragments inscribed for Nefertiti (now located in the Louvre and the Brooklyn Museum).

A previous theory that she fell into disgrace was discredited when deliberate erasures of monuments belonging to a queen of Akhenaten were shown to refer to Kiya instead.[16]

During Akhenaten's reign (and perhaps after), Nefertiti enjoyed unprecedented power. By the twelfth year of his reign, there is evidence she may have been elevated to the status of co-regent:[34] equal in status to the pharaoh, as may be depicted on the Coregency Stela.

New theories about Nefertiti's career as a Pharaoh

[edit]In 2012, the discovery of an inscription dated to Year 16, month 3 of Akhet, day 15 of the reign of Akhenaten was announced.[35]: 196–197 It was discovered within Quarry 320 in the largest wadi of the limestone quarry project at Dayr Abū Ḥinnis.[36] The five-line inscription, written in red ochre ink, mentions the presence of the "Great Royal Wife, His Beloved, Mistress of the Two Lands, Neferneferuaten Nefertiti".[35]: 197 [37] The final line of the inscription refers to ongoing building work being carried out under the authority of the king's scribe Penthu on the Small Aten Temple in Amarna.[38] The Year 16 ink inscription was translated as:

- "Regnal year 16, first month of the inundation season, day 15. May the King of Upper and Lower Egypt live, he who lives of Maat, the Lord of the Two Lands Neferkheperure Waenre, l.p.h. the Son of Re, who lives of Maat, the Lord of the Crowns Akhenaten, l.p.h., whose life span is long, living forever and ever, the King's Great Wife, his beloved, the lady of the two lands Neferneferuaten-Nefertiti, living forever and ever. Beloved of Re, the ruler of the two horizons, who rejoices in the horizon in his name of Re ///, who comes as the Aten. the /// the work of the Mansion of the Aten, under the authority of the king’s scribe Penthu, under the authority of overseer of work///."[39]

Van der Perre stresses that:

This inscription offers incontrovertible evidence that both Akhenaten and Nefertiti were still alive in the 16th year of his [Akhenaten's] reign and, more importantly, that they were still holding the same positions as at the start of their reign. This makes it necessary to rethink the final years of the Amarna Period.[40]

This means that Nefertiti was alive in the second to last year of Akhenaten's reign, and demonstrates that Akhenaten still ruled alone, with his wife by his side. Therefore, the rule of the female Amarna pharaoh known as Neferneferuaten must be placed between the death of Akhenaten and the accession of Tutankhamun. Neferneferuaten, the female pharaoh, specifically used the epithet 'Effective for her husband' in one of her cartouches,[31] which means she was either Nefertiti or her daughter Meritaten (who was married to king Smenkhkare). Moreover, unlike Meritaten, Nefertiti had already used the title "Neferneferuaten" by Year 5 of Akhenaten's reign in her own cartouches.[41]

The number of Egyptologists who today agree that the female pharaoh Neferneferuaten was Nefertiti include Chris Naunton,[42] Aidan Dodson,[43] Athena van der Perre,[44] Nozomu Kawai[45][7] and James Peter Allen since 2016 in a Göttinger Miszellen article.[46]

In his updated 2016 paper, James P. Allen now also identifies the female pharaoh as Neferneferuaten Nefertiti, and not Akhenaten's daughter who was named Neferneferuaten Tasherit (the younger) as he had previously suggested in a 2009 paper in memory of the late William J. Murnane. Allen states:

- "The evidence indicates Smenkhkare ruled only about a year at most....Smenkhkare's premature death probably no later than Akhenaten's Regnal Year 14 left only the one-to-four year old heir Tutankhuaten as putative heir....Tutankhamun must have been considered too young to be named coregent in his father's stead....To safeguard Tutankhamun's accession, Akhenaten also appointed a female coregent Ankheperure Neferneferuaten, to oversee the transition and probably to instruct him in the new religion. In 2009, I argued that this coregent was Akhenaten's fourth daughter, Neferneferuaten, both because it seemed a logical progression in his attempts to produce a son within each of his daughters as they reached puberty, and because evidence was lacking that the other Neferneferuaten, Nefertiti, was still alive in Akhenaten's final years. The Year 16 inscription noted [for the existence of Akhenaten's chief queen] at the beginning of this article solves the latter problem, and I (and my students) now think it likeliest that the coregent was in fact, Nefertiti. The arguments for this are more compelling than they are for the daughter.....Since Nefertiti was still chief queen in Regnal Year 16 [of Akhenaten], her Year 3 as pharaoh must have occurred two years after Akhenaten's death, and it was within those two years that the first steps towards reconciliation with Amun occurred. While little is known about the daughter other than her existence, Nefertiti had assumed pharaonic roles and prerogatives throughout Akhenaten’s reign, and the occasional epithet in her nomen Akhet-en-hyes “Beneficial for her husband,” both reflects a relationship that had already existed and mirrors Akhenaten's own nomen [Akh-en-Iten or 'The one who is beneficial to the Aten'],[47] which described his relationship not only with his god but also with his predecessor, the Tjehen-Aten “dazzling Aten,” Amenhotep III. Moreover, if as now seems probable, the appointment of a female coregent was intended not to ensure her own succession but that of the young Tutankhuaten, then it is far more likely that Akhenaten would have turned to the older more experienced woman who had served as his virtual co-ruler than to a young daughter who had just reached puberty barely three to six years older than the heir she was intended to safeguard.”[46]

Death and burial

[edit]If, as seems likely that Nefertiti was the female pharaoh ruler named Neferneferuaten, she outlived her husband Akhenaten and held great influence over the royal family. If this is the case, that influence and presumably Nefertiti's own life would have ended by Year 3 of Tutankhaten's reign when she died and the Boy King succeeded her. (1331 BC). In that year, Tutankhaten changed his name to Tutankhamun which is interpreted as evidence of his return to the official worship of Amun, and abandoned Amarna to return the capital to Memphis and Thebes according to Aidan Dodson.[5]

Other Egyptologists such as Athena van der Perre and Nozomu Kawai conclude that Nefertiti had an independent or sole rule and was not Tutankhamun's senior co-regent on the throne. Kawai states below:

- "The fact that a number of objects found in Tutankhamun's tomb had been made for the burial of Neferneferuaten [Nefertiti here], adapted and reinscribed for Tutankhamun's use, implies that Tutankhaten and his entourage did not want to recognize the preceding reign. Neferneferaten had assumed sole reign despite the fact that Tutankhaten, the crown prince, was the legitimate successor [to Akhenaten]. Instead of giving up her kingship to a young boy, Neferneferuaten may have wished to continue her sole rule not only because she was already reigning, but also because Tutankhaten was just a boy between five and 10 years old. Although Neferneferuaten began restoring the cults of Amun and other deities she also simultaneously maintained the cult of Aten at Amarna, resulting in a dissatisfied faction of [royal] officials [such as Ay and Horemheb] and priests who advocated a quick return to orthodoxy."[48]

Nefertiti's burial was intended to be made within the Royal Tomb as laid out in the Boundary Stelae.[49] It is possible that the unfinished annex of the Royal Tomb was intended for her use.[50] However, given that Akhenaten appears to have predeceased her it is highly unlikely she was ever buried there. One shabti is known to have been made for her.[51] The unfinished Tomb 29, which would have been of very similar dimensions to the Royal Tomb had it been finished, is the most likely candidate for a tomb begun for Nefertiti's exclusive use.[52] Given that it lacks a burial chamber, she was not interred there either.

In 1898, French archeologist Victor Loret found two female mummies among those cached inside the tomb of Amenhotep II in KV35 in the Valley of the Kings. These two mummies, known as 'The Elder Lady' and 'The Younger Lady', were identified as likely candidates of her remains.

An article in KMT magazine in 2001 suggested that the Elder Lady might be Nefertiti.[53] However, it was subsequently shown that the 'Elder Lady' is in fact Tiye, mother of Akhenaten. A lock of hair found in a coffinette bearing an inscription naming Queen Tiye proved a near perfect match to the hair of the 'Elder Lady'.[54] DNA analysis confirmed that she was the daughter of Tiye's parents Yuya and Thuya.[55]

On 9 June 2003 archaeologist Joann Fletcher, a specialist in ancient hair from the University of York in England, announced that Nefertiti's mummy may have been the Younger Lady. This theory was criticised by Zahi Hawass and several other Egyptologists.[56] In a subsequent research project led by Hawass, the mummy was put through CT scan analysis and DNA analysis. Researchers concluded that she was Tutankhamun's biological mother, an unnamed daughter of Amenhotep III and Tiye, not Nefertiti.[21]

In 2015, English archaeologist Nicholas Reeves announced that high resolution scans revealed voids behind the walls of Tutankhamun's tomb which he proposed to be the burial chamber of Nefertiti,[57][58] but subsequent radar scans showed that there are no hidden chambers.[59][60]

KV21B mummy

[edit]One of the two female mummies found in KV21 has been suggested as the body of Nefertiti. DNA analysis did not yield enough data to make a definitive identification but confirmed she was a member of the Eighteenth Dynasty royal line.[61] CT-scanning revealed she was about 45 at the time of her death; her left arm had been bent over her chest in the 'queenly' pose. The possible identification is based on her association with the mummy tentatively identified as Ankhesenamun. It is suggested that just as a mother and daughter (Tiye and the Younger Lady) were found lying together in KV35, the same was true of these mummies.[62]

Hittite letters

[edit]A document was found in the ancient Hittite capital of Hattusa which dates to the Amarna period. The document is part of the so-called Deeds of Suppiluliuma I. While laying siege to Karkemish, the Hittite ruler receives a letter from the Egyptian queen. The letter reads:[63]

My husband has died and I have no son. They say about you that you have many sons. You might give me one of your sons to become my husband. I would not wish to take one of my subjects as a husband... I am afraid.

This proposal is considered extraordinary as New Kingdom royal women never married foreign royalty.[64] Suppiluliuma I was understandably surprised and exclaimed to his courtiers:[63]

Nothing like this has happened to me in my entire life!

Understandably, he was wary, and had an envoy investigate the situation, but by so doing, he missed his chance to bring Egypt into his empire.[63] He eventually did send one of his sons, Zannanza, but the prince died, perhaps murdered, en route.[65][66]

The identity of the queen who wrote the letter is uncertain. She is called Dakhamunzu in the Hittite annals, a translation of the Egyptian title Ta hemet nesu (The King's Wife).[67][68][69] The possible candidates are Nefertiti, Meritaten,[70] and Ankhesenamun. Ankhesenamun once seemed the likeliest, since there were no candidates for the throne on the death of her husband, Tutankhamun, whereas Akhenaten had at least two legitimate successors. But this was based on the assumption of a 27-year reign for the last 18th Dynasty pharaoh, Horemheb, who is now accepted to have had a shorter reign of only 14 years. This makes the deceased Egyptian king appear to be Akhenaten instead, rather than Tutankhamun.[citation needed] Furthermore, the phrase regarding marriage to 'one of my subjects' (translated by some as 'servants') is possibly either a reference to the Grand Vizier Ay or a secondary member of the Egyptian royal family line. Since Nefertiti was depicted as being as powerful as her husband in official monuments smiting Egypt's enemies, she might be the Dakhamunzu in the Amarna correspondence, as Nicholas Reeves believes.[71]

Gallery

[edit]-

Headless bust of Akhenaten or Nefertiti. Part of a composite red quartzite statue. Intentional damage. Four pairs of early Aten cartouches. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

-

Limestone statuette of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, or Amenhotep III and Tiye,[72] and a princess. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

-

Limestone relief fragment. A princess holding sistrum behind Nefertiti, who is partially seen. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

-

Siliceous limestone fragment relief of Nefertiti. Extreme style of portrait. Reign of Akhenaten, probably early Amarna Period. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

-

Granite head statue of Nefertiti. The securing post at head apex allows for different hairstyles to adorn the head. Altes Museum, Berlin.

-

Head statue of Nefertiti, Altes Museum, Berlin.

-

Akhenaten, Nefertiti and their daughters before the Aten. Stela of Akhenaten and his family, Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

-

Nefertiti offering oil to the Aten. Brooklyn Museum.

-

Relief fragment with Nefertiti, Brooklyn Museum.

-

Akhenaten and Nefertiti. Louvre Museum, Paris.

-

Boundary stele of Amarna with Nefertiti and her daughter, princess Meketaten, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

-

Limestone relief of Nefertiti kissing one of her daughters, Brooklyn Museum.

-

Talatat with an aged Nefertiti, Brooklyn Museum.

Cultural depictions

[edit]- Nefertiti was portrayed by Geraldine Chaplin in Nefertiti and Akhenaton (1973), Mexican short film by Raul Araiza.

- Nefertiti was portrayed again by Riann Steele in Doctor Who (2012), in the episode Dinosaurs on a Spaceship.

- Nefertiti (presented as the same person as Neferneferuaten) is a key part of the archaeological topics in Jacqueline Benson's 2024 historical fantasy novel, Tomb of the Sun King.

References

[edit]- ^ "Akhenaton". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 26 May 2007.

- ^ von Beckerath, Jürgen (1997). Chronologie des Pharaonischen Ägypten. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern. p. 190.

- ^ "Nefertit". Collins Dictionary. n.d. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ Freed, R. E.; D'Auria, S.; Markowitz, Y. J. (1999). Pharaohs of the Sun: Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamen. Leiden: Museum of Fine Arts.

- ^ a b c d Dodson, Aidan (2009). Amarna Sunset: Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Ay, Horemheb, and the Egyptian Counter-Reformation (PDF). The American University in Cairo Press. pp. 36–38. ISBN 978-977-416-304-3.

- ^ Van de Perre, Athena (2014). "The Year 16 graffito of Akhenaten in Dayr Abū Ḥinnis: A contribution to the study of the later years of Nefertiti". Journal of Egyptian History. 7: 67–108. doi:10.1163/18741665-12340014.

- ^ a b Nozomu Kawai in "The Time of Tutankhamun: What the new evidence reveals in SCRIBE: The Magazine of the American Research Center in Egypt, Unlocking Tutankhamun, Spring 2022, pp.46-47

- ^ Breger, Claudia (2006). "The 'Berlin' Nefertiti Bust". In Regina Schulte (ed.). The Body of the Queen: Gender and Rule in the Courtly World, 1500–2000. Berghahn Book. p. 285. ISBN 1-84545-159-7.

- ^ Dodson, A. (2020). Nefertiti, Queen and Pharaoh of Egypt: Her Life and Afterlife. The American University in Cairo Press. p. 26.

- ^ Grajetzki, Wolfram (2005). Ancient Egyptian Queens: A Hieroglyphic Dictionary. London: Golden House Publications. ISBN 978-0-9547218-9-3.

- ^ a b c d e Dodson (2016), p. 87.

- ^ Schenkel, W. (1983). Zur Rekonstruktion der deverbalen Nominalbildung des Ägyptischen. Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz. pp. 212, 214, 247.

- ^ Allen, James P. (24 July 2014). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05364-9.

- ^ Norman De Garis Davies, The rock tombs of el-Amarna, Parts I and II: Part 1 The tomb of Meryra & Part 2 The tombs of Panehesy and Meyra II, Egypt Exploration Society (2004)

- ^ Norman De Garis Davies, The rock tombs of el-Amarna, Parts V and VI: Part 5 Smaller tombs and boundary stelae & Part 6 Tombs of Parennefer, Tutu and Ay, Egypt Exploration Society (2004)

- ^ a b c Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05128-3.

- ^ van Dijk, Jacobus (1996). "Horemheb and the Struggle for the Throne of Tutankhamun" (PDF). Bulletin of the Australian Centre for Egyptology. 7: 32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- ^ van Dijk, J. (1996). "Horemheb and the Struggle for the Throne of Tutankhamun" (PDF). Bulletin of the Australian Centre for Egyptology: 31–32. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ Dodson (2016), p. 87–88.

- ^ a b c d e Tyldesley, Joyce (1998). Nefertiti: Egypt's Sun Queen. Penguin. ISBN 0-670-86998-8.

- ^ a b Hawas, Zahi; Saleem, Sahar N. (2016). Scanning the Pharaohs: CT Imaging of the New Kingdom Royal Mummies. New York: The American University in Cairo Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-977-416-673-0.

- ^ Redford, Donald B. (1987). Akhenaten, the Heretic King. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691002170.

- ^ Montserrat, Dominic (2003). Akhenaten: History, Fantasy and Ancient Egypt. Psychology Press.

- ^ Trope, B.; Quirke, S.; Lacovara, P. (2005). Excavating Egypt. Great Discoveries from the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University. ISBN 1-928917-06-2.

- ^ Murnane, William J. (1995). Texts from the Amarna Period in Egypt. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 1-55540-966-0.

- ^ a b c van der Perre 2014.

- ^ David Aston, RADIOCARBON, WINE JARS AND NEW KINGDOM CHRONOLOGY*, Ägypten und Levante/Egypt and the Levant 22, 2012, pp.293-294

- ^ Aidan Dodson, “The Royal Tomb at Amarna Revisited” p.53 in THE JOURNAL OF THE SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF EGYPTIAN ANTIQUITIES (ed: Sarah L. Ketchley and Edmund S. Meltzer), VOLUME XLV, Toronto Canada, 2018-2019

- ^ "Nefertiti - Ancient History - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ AncientHistory (28 April 2017), Nefertiti's Odyssey - National Geographic Documentary, archived from the original on 6 November 2019, retrieved 26 October 2017

- ^ a b Brand, P. (ed.). "Under a Deep Blue Starry Sky" (PDF). Causing His Name to Live: Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane. pp. 17–21. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ AncientHistory (16 December 2014). 'Queen Nefertiti' The Most Beautiful Face of Egypt (Discovery Channel). Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ Badger Utopia (11 August 2017). Nefertiti - Mummy Queen of Mystery. Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ Reeves, Nicholas. Akhenaten: Egypt's False Prophet. p.172 Thames & Hudson. 2005. ISBN 0-500-28552-7

- ^ a b Van der Perre, Athena (2012). Seyfried, Friederike (ed.). In the Light of Amarna: 100 Years of the Nefertiti discovery. Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. ISBN 978-3-86568-848-4.

- ^ van der Perre 2014, p. 68.

- ^ van der Perre 2014, p. 73.

- ^ van der Perre 2014, p. 76.

- ^ Van der Perre, Athena (2014). "The Year 16 Graffito of Akhenaten in Dayr Abu Hinnis. A Contribution to the Study of the Later Years of Nefertiti". Journal of Egyptian History. 7 (1): 72–73. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ van der Perre 2014, p. 77.

- ^ Aidan Dodson, Nefertiti, Queen and Pharaoh of Egypt_ Her Life and Afterlife, The American University in Cairo Press (2020), p.26

- ^ January 28, 2020 Twitter/X post

- ^ in Guardian of Ancient Egypt Studies in Honor of Zahi Hawass, edited by Janice Kamrin, Miroslav Bárta, Salima Ikram, Mark Lehner & Mohamed Megahed, Prague, Charles University, Faculty of Arts, Volume 1, 2020, pp.357-365

- ^ The Year 16 graffito of Akhenaten in Dayr Abū Ḥinnis. A Contribution to the Study of the Later Years of Nefertiti, Journal of Egyptian History 7 (2014), pp.95-96

- ^ Nozomu Kawai, "Neferneferuaten from the Tomb of Tutankhamun Revisited" in Wonderful Things Essays in Honor of Nicholas Reeves, Lockwood Press, (2023), p. 121

- ^ a b James P. Allen, “The Amarna Succession Revised,” GM 249 (2016), pp.10-11

- ^ Ronald J. Leprohon, "The Great Name: Ancient Egyptian Royal Titulary", SBL Press. 2013. ISBN 978-1-58983-736-2. pp.104–105

- ^ Nozomu Kawai in "The Time of Tutankhamun: What the new evidence reveals" in SCRIBE: The Magazine of the American Research Center in Egypt, Unlocking Tutankhamun, Spring 2022, pp.46-47

- ^ Murnane, William J. (1995). Texts from the Amarna period in Egypt. United States of America: Scholars Press. p. 78. ISBN 1-55540-966-0.

- ^ Dodson, Aidan (2018). Amarna sunset : Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Ay, Horemheb, and the Egyptian counter-reformation (Revised ed.). Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-977-416-859-8.

- ^ Kemp, Barry (2014). The city of Akhenaten and Nefertiti : Amarna and its people. New York: Thames & Hudson. p. 255. ISBN 978-0-500-29120-7.

- ^ Kemp, Barry. The Amarna Royal Tombs at Amarna (PDF). p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ James, Susan E. (Summer 2001). "Who is Mummy Elder Lady?". KMT. Vol. 12, no. 2.

- ^ Harris, James E.; Wente, Edward F.; Cox, Charles F.; El Nawaway, Ibrahim; Kowalski, Charles J.; Storey, Arthur T.; Russell, William R.; Ponitz, Paul V.; Walker, Geoffrey F. (1978). "Mummy of the "Elder Lady" in the Tomb of Amenhotep II: Egyptian Museum Catalog Number 61070". Science. 200 (4346): 1149–51. Bibcode:1978Sci...200.1149H. doi:10.1126/science.349693. JSTOR 1746491. PMID 349693.

- ^ Hawass, Z.; Gad, Y. Z.; Ismail, S.; Khairat, R.; Fathalla, D.; Hasan, N.; Ahmed, A.; Elleithy, H.; Ball, M.; Gaballah, F.; Wasef, S.; Fateen, M.; Amer, H.; Gostner, P.; Selim, A.; Zink, A.; Pusch, C. M. (2010). "Ancestry and pathology in King Tutankhamun's family". JAMA. 303 (7): 638–47. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.121. PMID 20159872.

- ^ "Weekly Column - Dr. Zahi Hawass". 27 September 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- ^ Martin, Sean (11 August 2015). "Archaeologist believes hidden passageway in tomb of Tutankhamun leads to resting place of Nefertiti". International Business Times.

- ^ "Radar Scans in King Tut's Tomb Suggest Hidden Chambers". National Geographic News. 28 November 2015. Archived from the original on 30 November 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ Sambuelli, Luigi; Comina, Cesare; Catanzariti, Gianluca; Barsuglia, Filippo; Morelli, Gianfranco; Porcelli, Francesco (May 2019). "The third KV62 radar scan: Searching for hidden chambers adjacent to Tutankhamun's tomb". Journal of Cultural Heritage. 39: 8. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2019.04.001. S2CID 164859865.

- ^ Sambuelli, Luigi; Comina, Cesare; Catanzariti, Gianluca; Barsuglia, Filippo; Morelli, Gianfranco; Porcelli, Francesco (May 2019). "The third KV62 radar scan: Searching for hidden chambers adjacent to Tutankhamun's tomb". Journal of Cultural Heritage. 39: 9. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2019.04.001. S2CID 164859865.

- ^ Hawass, Zahi; Gad, Yehia Z.; Somaia, Ismail; Khairat, Rabab; Fathalla, Dina; Hasan, Naglaa; Ahmed, Amal; Elleithy, Hisham; Ball, Markus; Gaballah, Fawzi; Wasef, Sally; Fateen, Mohamed; Amer, Hany; Gostner, Paul; Selim, Ashraf; Zink, Albert; Pusch, Carsten M. (17 February 2010). "Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family". Journal of the American Medical Association. 303 (7). Chicago, Illinois: American Medical Association: 638–647. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.121. ISSN 1538-3598. PMID 20159872. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ Hawass, Zahi; Saleem, Sahar N. (2016). Scanning the Pharaohs: CT Imaging of the New Kingdom Royal Mummies. New York: American University in Cairo Press. pp. 132–142. ISBN 978-977-416-673-0.

- ^ a b c Güterbock, Hans Gustav (June 1956). "The Deeds of Suppiluliuma as Told by His Son, Mursili II (Continued)". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 10 (3): 75–98. doi:10.2307/1359312. JSTOR 1359312. S2CID 163670780.

- ^ Schulman, Alan R. (1979). "Diplomatic Marriage in the Egyptian New Kingdom". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 38 (3): 179–180. doi:10.1086/372739. JSTOR 544713. S2CID 161228521.

- ^ Güterbock, Hans Gustav (September 1956). "The Deeds of Suppiluliuma as Told by His Son, Mursili II". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 10 (4): 107–130. doi:10.2307/1359585. JSTOR 1359585. S2CID 224824543.

- ^ Amelie Kuhrt (1997). The Ancient Middle East c. 3000 – 330 BC. Vol. 1. London: Routledge. p. 254.

- ^ Lloyd, Alan B. (6 May 2010). A Companion to Ancient Egypt. John Wiley & Sons. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-4443-2006-0. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Darnell, John Coleman; Manassa, Colleen (3 August 2007). Tutankhamun's Armies: Battle and Conquest During Ancient Egypt's Late Eighteenth Dynasty. John Wiley & Sons. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-471-74358-3. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Matthews, Roger; Roemer, Cornelia, eds. (16 September 2016). Ancient Perspectives on Egypt. Routledge. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-315-43491-9. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Grajetzki, Wolfram (2000). Ancient Egyptian Queens; a hieroglyphic dictionary. London: Golden House. p. 64.

- ^ Nicholas Reeves,Tutankhamun's Mask Reconsidered BES 19 (2014), pp.523

- ^ Johnson, W. Raymond (1996). "Amenhotep III and Amarna: Some New Considerations". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 82: 76. doi:10.1177/030751339608200112. JSTOR 3822115. S2CID 193461821.

Works cited

[edit]- Dodson, Aidan (2020). Nefertiti, Queen and Pharaoh of Egypt, Her Life and Afterlife. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 9789774169908.

- Dodson, Aidan (2016) [2014]. Amarna Sunrise: Egypt from Golden Age to Age of Heresy. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 9781617975608.

- van der Perre, Athena (2014). "The Year 16 graffito of Akhenaten in Dayr Abū Ḥinnis. A Contribution to the Study of the Later Years of Nefertiti". Journal of Egyptian History. 7 (1): 67–106. doi:10.1163/18741665-12340014.

- Juan Antonio Belmonte, "Nefertiti strikes back! A comprehensive multidisciplinary approach for the end of the Amarna Period" in The Star Who Appears in Thebes. Studies in Honour of Jiro Kondo (eds: Nozomu Kawai & Benedict G. Davies), Abercrombie Press, 2022, ISBN 9781912246137

- Maria M. Kloska, The Role of Nefertiti in the Religion and the Politics of the Amarna Period, Instytut Archeologii, UAM Poznań, Vol.21 2016, pp.149-175 PDF

External links

[edit]- The Disappearance of Queen Nefertiti: Egypt’s Greatest Mystery — by historian Tamara Eidelman on YouTube

- Staatliche Museen zu Berlin: Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection Archived 2010-07-02 at the Wayback Machine

- C. Nicholas Reeves: The Burial of Nefertiti?

- Habicht M. et al: Who else might be in Pharaoh Tutankhamun's tomb (KV 62, c. 1325 BC)?

- A 3D model of a bust of Nefertiti

Nefertiti

View on GrokipediaNefertiti was the Great Royal Wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten during Egypt's 18th Dynasty in the 14th century BCE, serving as a central figure in the Amarna Period's religious and artistic transformations.[1][2] Her prominence is evidenced by extensive depictions in temple reliefs and boundary stelae at Akhetaten (modern Amarna), where she appears alongside Akhenaten in rituals honoring the Aten sun disk, suggesting a co-equal role in promoting this near-monotheistic cult that supplanted traditional polytheism.[3][4] Nefertiti bore at least six daughters with Akhenaten, including Meritaten and Ankhesenamun, though her own origins remain obscure, with no definitive records of her parentage beyond possible non-royal Mitanni ties inferred from diplomatic artifacts.[1] The queen's iconic painted limestone bust, discovered on December 6, 1912, by German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt during excavations at Amarna's sculptor workshop, exemplifies the distinctive Amarna art style with its elongated features and vivid pigmentation, now housed in Berlin's Neues Museum.[5] This artifact, alongside numerous statues and inscriptions, underscores her elevated status, as she receives offerings and smites enemies in scenes typically reserved for kings, fueling scholarly debate over whether she exercised co-regency or briefly ruled as pharaoh under names like Smenkhkare—claims supported by cartouche analyses but contested due to limited epigraphic evidence and post-Amarna damnatio memoriae.[6][4] Nefertiti vanishes from records after Akhenaten's 12th regnal year (c. 1336 BCE), her tomb unfinished and fate unknown, amid the regime's collapse and restoration of orthodox cults under Tutankhamun.[1][6]

Identity and Names

Etymology and Linguistic Analysis

The name Nefertiti represents the conventional Egyptological vocalization of the ancient Egyptian phrase nfr.t-ỉỉ.ty, literally translating to "the beautiful one has come."[7][8] This interpretation breaks down into nfr.t, the feminine nominal form of the adjective nfr signifying "beautiful," "good," or "perfect," followed by ỉỉ.ty, a feminine ending derived from the verb ỉỉ ("to come") in a perfective or stative construction denoting arrival or presence.[9] In terms of hieroglyphic writing, the name typically appears as a sequence incorporating the nfr ideogram (Gardiner sign F35, depicting a heart and trachea symbolizing beauty), suffixed with phonetic complements for t (often N35, a loaf of bread) and ỉỉ.t(y) (using signs like the reed leaf for i and cobra or hand for tj), sometimes enclosed in a cartouche to denote royal status.[10] The construction functions as a verbless nominal sentence common in Egyptian onomastics, where the adjective nfr.t serves as the subject and ỉỉ.ty as a circumstantial or participial modifier, emphasizing an auspicious arrival rather than a literal biographical event.[7] Ancient pronunciation remains conjectural due to the consonantal nature of Egyptian script, with vowels unrecorded; reconstructions approximate nafra.ti:ta or similar based on comparative Afro-Asiatic linguistics and Coptic reflexes, diverging from the modern Nefertiti (/nɛfərˈtiːti/).[11] No evidence suggests foreign linguistic origins for the name, which aligns fully with Middle Egyptian morphology and vocabulary attested from the 18th Dynasty onward.[8]Titles and Epithets in Inscriptions

Nefertiti's name appears in inscriptions from Akhenaten's reign enclosed within royal cartouches as Neferneferuaten Nefertiti, where Neferneferuaten means "beautiful are the beauties of Aten" and Nefertiti translates to "the beautiful one has come," reflecting the Amarna Period's emphasis on Aten worship.[10] This full form is attested in reliefs and stelae from sites like Karnak and Amarna, marking her elevated status alongside the pharaoh.[10] Her primary title as chief queen was ḥmt-nswt-wrt, "Great Royal Wife," frequently paired with epithets denoting affection and divine favor, such as ḥmt-nswt-wrt mryt.f, "Great Royal Wife, his beloved."[12] Additional titles in inscriptions include ỉr.yt-pꜥ.t, "Hereditary Princess," wrt-ḥz.wt, "Great of Praises," nbt-ỉm.ꜣ.t, "Lady of Grace," bnr.t-mr.wt, "Sweet of Love," and nbt-tꜣ.wy, "Lady of the Two Lands," which underscore her royal lineage, charm, and dominion over Egypt.[12] These appear in temple reliefs and boundary stelae at Akhetaten (Amarna), where her role is depicted in rituals honoring Aten.[12] In Aten-centric contexts, inscriptions adapt traditional epithets to align with monotheistic theology, portraying Nefertiti as intimately linked to the solar deity, though without explicit priestly titles like those of earlier queens.[1] Fragments from Amarna, such as those in the Petrie Museum, preserve her alongside Akhenaten's cartouches with qualifiers like "Great King's Wife" following royal epithets, evidencing her prominence in official propaganda.[13]| Title (Transliteration) | Translation | Attestation Context |

|---|---|---|

| ḥmt-nswt-wrt | Great Royal Wife | Temple reliefs, stelae at Amarna and Karnak[12] |

| ḥmt-nswt-wrt mryt.f | Great Royal Wife, his beloved | Inscriptions emphasizing personal bond with Akhenaten[12] |

| wrt-ḥz.wt | Great of Praises | Royal titulary in Amarna Period art[12] |

| nbt-ỉm.ꜣ.t | Lady of Grace | Epithet in queenly depictions[12] |

Origins and Early Life

Theories on Parentage and Social Background

The parentage of Nefertiti remains unknown from direct contemporary evidence, as no inscriptions explicitly name her parents, leaving theories reliant on indirect associations and later attestations.[2][14] The most widely accepted hypothesis identifies her as the daughter of Ay, a non-royal official who rose to vizier and eventual pharaoh, and an unnamed earlier wife distinct from his documented spouse Tey. This view stems from Tey's attested titles as "royal nurse" and "one who rears" (menit-nt-rst) for Nefertiti, implying intimate household involvement consistent with stepmotherly or maternal roles, alongside Ay's Akhmim origins and his own stela invoking Nefertiti's protection in the afterlife.[15][14] Ay's family ties to Akhmim, a provincial hub also connected to Queen Tiye's lineage, further support Nefertiti's integration into court circles through established administrative networks rather than divine royalty.[2][15] Challenges to Ay's paternity include the absence of a explicit "daughter of Ay" declaration in Amarna records and interpretations of Ay's son Nakhtmin's inscriptions suggesting an intervening wife, though these do not preclude Nefertiti's birth to a prior union.[14][8] A minority theory proposes Nefertiti as a Mitannian princess, equated with Tadukhipa (or Taduhepa), dispatched circa 1357 BCE amid Egypt-Mitanni diplomacy to secure alliances against Hittite threats, with her name nfrt-jtj ("the beautiful one has come") interpreted as denoting foreign arrival.[16][17] Proponents cite parallels in diplomatic bride exchanges, such as those involving Amenhotep III, and potential name adaptations from Hurrian elements.[16] This foreign origin lacks corroboration from iconography, which depicts Nefertiti with standard Egyptian features and no Mitannian regalia, and faces timeline discrepancies, as Tadukhipa’s documented betrothal to Amenhotep III predates Akhenaten's reign without clear transfer evidence.[8] Egyptologists like Aidan Dodson dismiss it in favor of indigenous nobility, noting the theory's reliance on speculative etymology over archaeological attestation.[8] Nefertiti's social background aligns with upwardly mobile provincial elites, evidenced by Ay's career trajectory from "overseer of horses" under Amenhotep III to key Amarna administrator, reflecting merit-based advancement in the 18th Dynasty's late phase amid religious upheavals.[15][14] Her pre-marriage obscurity and lack of royal epithets indicate non-pharaonic stock, enabling her prominence through alliance with Akhenaten rather than inherited privilege, a pattern atypical yet feasible in the Amarna court's disruption of Theban hierarchies.[2][18]Marriage to Akhenaten and Family Dynamics

Nefertiti married Amenhotep IV, who later adopted the name Akhenaten upon his accession to the throne circa 1353 BCE, though the precise date of their union remains uncertain and is believed to have occurred prior to his coronation.[2][8] Early depictions of the couple together in temple reliefs and boundary stelae from Akhetaten suggest their partnership predated the full implementation of the Atenist reforms.[19] The marriage produced six daughters, whose names and order of birth are attested in Amarna-period inscriptions and reliefs: Meritaten (born possibly before Akhenaten's reign), Meketaten, Ankhesenpaaten (later Ankhesenamun, wife of Tutankhamun), Neferneferuaten tasherit, Neferneferure, and Setepenre.[20][21] No sons are definitively attributed to Nefertiti in surviving records, with genetic analyses indicating Tutankhamun as a son of Akhenaten by another consort, likely Kiya.[3] Family dynamics are prominently illustrated in Amarna art, where Akhenaten and Nefertiti appear as a cohesive unit adoring the Aten sun disk, often with their daughters receiving life-giving rays alongside them, emphasizing a shared divine role in the new monotheistic cult.[22] Reliefs depict intimate familial scenes, such as the royal couple embracing or nursing infants, diverging from traditional pharaonic iconography to portray emotional closeness and equality in religious devotion.[18][23] This artistic emphasis on domestic harmony underscores Nefertiti's elevated status, with her titles like "Great Royal Wife" and joint appearances in smiting scenes indicating collaborative authority rather than subordination.[2]Role in the Amarna Period

Political and Administrative Influence

Nefertiti held titles that extended beyond traditional queenly roles, including "Mistress of Upper and Lower Egypt," a designation evoking pharaonic dominion over the unified realm, as attested in Karnak inscriptions.[24] Other epithets, such as "Lady of the Two Lands" and "the leading woman of all the nobles, great in the palace," underscore her elevated status within the administrative hierarchy.[18] [25] These titles, rare for non-ruling queens, suggest her involvement in symbolic aspects of governance, though direct evidence of day-to-day administration remains limited to interpretive depictions rather than explicit records of policy-making. Artistic representations from the Amarna period portray Nefertiti in politically charged poses, such as smiting enemies from a boat, a motif conventionally associated with royal military prowess and the maintenance of ma'at (cosmic order).[18] She is also shown offering to the Aten independently or alongside Akhenaten on equal terms, participating in rituals that reinforced the state's religious-political ideology.[26] Such iconography, including her frequent appearance in temple decoration programs at Karnak and the Gem-pa-Aten, indicates an unprecedented advisory or representational role in legitimizing Akhenaten's reforms.[26] The boundary stelae of Akhetaten (Amarna) further highlight her administrative prominence, featuring rock-cut statues of Nefertiti with Akhenaten and their daughters at key sites, and provisions for her burial in the royal tomb, integrating her into the foundational narrative of the new capital.[27] These monuments, erected circa 1349–1336 BCE, demarcated the sacred boundaries chosen by Akhenaten, with Nefertiti's inclusion emphasizing her as a co-pillar of the regime's spatial and ideological order.[25] While scholarly consensus views her influence as substantial in ceremonial and propagandistic spheres, debates persist on the extent of practical administrative authority, with some attributing greater agency to her religious oversight than to bureaucratic control.[18]Religious Prominence in Aten Worship

Nefertiti occupied a central position in the Aten cult, forming a divine triad with Akhenaten and the Aten, analogous to the mythological pair Shu and Tefnut emanating from Atum.[3] [4] This triad structure elevated her to semi-divine status, with artistic depictions showing the Aten's rays extending life-giving hands exclusively to the royal family, underscoring their role as sole intermediaries between the deity and humanity.[3] In boundary stelae erected around Akhetaten between regnal years 5 and 8, Nefertiti is prominently featured alongside Akhenaten in proclamations establishing the city as the exclusive center for Aten worship.[27] These stelae include rock-cut statues of the royal couple and their daughters adoring the Aten, and specify a dedicated "Sun Temple of the Great King’s Wife Nefertiti" within the planned cult complex.[27] Her burial was mandated in the eastern hills of Akhetaten, paralleling Akhenaten's own, to ensure eternal proximity to the Aten's domain.[27] Reliefs and inscriptions from Amarna temples, such as the Hut-Benben, record Nefertiti's name more frequently than Akhenaten's in certain contexts—appearing 564 times compared to his 329—and associate her with 67 offering tables versus his 3, indicating her active participation in cultic offerings.[4] She bore the title of High Priestess-Musician, described as the one who soothes the Aten with her voice and hands through sistrum-playing, and is shown performing priestly duties like sacrifices alongside her daughter Meritaten.[4] Talatat blocks depict her in ritual scenes, including smiting enemies on ceremonial barques, a motif traditionally reserved for pharaohs, further evidencing her elevated religious authority.[4] Sunshade of Re temples at Amarna, dedicated to royal women including Nefertiti, linked them to the Aten's regenerative solar powers, reinforcing female roles in sustaining the cult's cosmic order.[3] Unlike traditional Egyptian priesthoods, the Aten religion marginalized professional clergy, positioning the royal family— with Nefertiti as co-mediator—as the exclusive conduit for divine interaction.[3]Artistic Representations and Iconography

Nefertiti's artistic depictions emerged during the Amarna Period under Akhenaten's reign (circa 1353–1336 BCE), featuring a revolutionary style that departed from traditional Egyptian canon with elongated crania, narrow waists, protruding bellies, and androgynous proportions emphasizing familial intimacy and Aten worship.[22] These traits, observed in limestone reliefs and sculptures from Amarna workshops, reflect a deliberate aesthetic shift possibly tied to the royal family's idealized physiology or theological symbolism, rather than mere naturalism.[19] The most renowned representation is the painted limestone bust discovered in 1912 at Amarna's sculptor's workshop, measuring 47 cm in height and depicting Nefertiti with a slender neck, full lips, and asymmetrical eyes—the left detailed with inlaid crystal and ebony, the right unfinished or socketed for an insert.[28] Originally coated in stucco and vividly colored, with a blue crown, red upper body, and gold jewelry, the bust exemplifies workshop experimentation in portraiture, capturing subtle asymmetries like a drooping chin and slanted eyes akin to Akhenaten's features.[26] Reliefs and statues further illustrate Nefertiti in dynamic roles, such as striding figures offering to the Aten sun disk with arms raised in adoration, or smiting enemies from a boat, adopting pharaonic postures traditionally male.[3] Family scenes on house altars and tomb walls show her with Akhenaten and daughters, rays of the Aten extending hands to offer life (ankh symbols), underscoring her prominence in cultic rituals depicted on talatat blocks and stelae from circa 1350 BCE.[23] Iconographically, Nefertiti is distinguished by her tall, flat-topped blue crown—unique to her—adorned with a broad multicolored ribbon and rearing uraeus cobra signifying divine protection and royal authority, often positioned to mirror Akhenaten's khepresh crown in balanced duality.[29] This headdress, appearing in reliefs like those from Meryre's tomb, integrates with Aten cartouches and epithets, symbolizing her as the king's counterpart in monotheistic devotion, while avoiding veneration of other deities.[30] Such elements, rendered in sunk or raised relief on limestone, highlight her elevated status without equating to independent pharaonic iconography.[31]Disappearance and Theories of Later Role

Chronological Evidence from Year 12 Onward

In the 12th regnal year of Akhenaten, Nefertiti is attested in multiple inscriptions and reliefs at Amarna, including depictions of foreign tribute presentations in the tombs of officials Huya and Meryre II, dated specifically to the 2nd month of Peret, day 8, where she receives tribute alongside the king.[32] These scenes underscore her continued visibility in official records during this period of peak Amarna artistic production. Additionally, an inscription linked to the death of their daughter Meketaten, estimated to November 21 of year 12 (circa 1338 BCE), places Nefertiti in a mourning context within the royal tomb at Amarna, marking one of the last detailed familial depictions before her reduced prominence.[32] Post-year 12 attestations are sparse, with no confirmed dated inscriptions between years 13 and 15 explicitly naming or depicting Nefertiti, reflecting a potential shift in her public role or documentation practices amid ongoing Atenist reforms and administrative changes at Amarna.[33] This scarcity has fueled debates, but empirical evidence from quarry marks and undatable fragments suggests continuity in her status without firm chronological anchors until later.[34] A pivotal discovery in 2012 at the Dayr Abū Ḥinnis limestone quarry provides the latest dated evidence: a building inscription explicitly referencing Akhenaten and Nefertiti as the ruling couple in year 16, confirming her survival and retention of the title ḥmt-nṯr-wˁt nfr-nfr.w-ꜥtn (Great Royal Wife Neferneferuaten) at that stage.[35] [33] This graffito, carved in the context of resource extraction for Amarna construction, represents the highest regnal year attestation for Nefertiti and refutes earlier assumptions of her death or demotion by year 12, though it does not clarify her activities.[35] Beyond year 16, no dated inscriptions or reliefs mention Nefertiti, aligning with the onset of succession anomalies in the late Amarna period, including the emergence of figures like Smenkhkare and the transition to Tutankhamun, without direct linkage to her.[33] Wine jar dockets from years 17 and later reference Akhenaten's reign but omit Nefertiti, indicating a documentary gap rather than conclusive absence.[33] This evidentiary pattern—abundant pre-year 12, selective in year 12, minimal thereafter—highlights the limits of current archaeological data for reconstructing her final years.Hypothesis of Coregency or Succession as Pharaoh

One prominent hypothesis suggests that Nefertiti assumed the role of coregent with Akhenaten during the later years of his reign, evidenced by her unprecedented prominence in Amarna art and inscriptions where she performs actions traditionally exclusive to pharaohs, such as smiting enemies of Egypt.[36] These depictions, including reliefs showing her wielding weapons against captives from a royal barge, align with iconography typically reserved for kings, indicating a possible elevation to equal partnership in governance around regnal year 12 or later.[36] Additionally, her adoption of epithets like "Neferneferuaten," which later appears as a throne name for a ruler, supports interpretations of shared royal authority, as this title emphasizes beauty and Aten's favor in a manner echoing her queenly nomenclature.[1] A related theory proposes that Nefertiti succeeded Akhenaten as pharaoh upon his death circa 1336 BC, ruling briefly under the name Neferneferuaten before the ascension of Tutankhamun around 1332 BC.[36] This identification draws from the feminine grammatical endings and prenomen variants in inscriptions attributed to Neferneferuaten, distinguishing this figure as a female ruler distinct from the subsequent Smenkhkare, whose gender remains debated.[1] An inscription from Akhenaten's regnal year 16, discovered at Deir el-Bersha, confirms Nefertiti's survival and status as chief queen into the final phases of his rule, positioning her as a logical successor during the transitional instability following the Amarna religious reforms.[1] Proponents argue this short reign, potentially lasting one to three years, would explain the scarcity of direct attributions while accounting for continuity in Atenist iconography before the restoration of traditional cults under Tutankhamun.[36] Supporting artifacts include limestone reliefs from Amarna now in collections like the Ashmolean Museum, where Nefertiti appears with pharaonic crowns such as the double uraeus and blue war crown, symbols of dominion over Upper and Lower Egypt.[36] Titles ascribed to her, including "Mistress of the Two Lands," further imply administrative and ritual authority beyond conventional queenship, potentially reflecting a deliberate blurring of gender roles in Akhenaten's monotheistic regime.[36] While these elements form a circumstantial case, the hypothesis underscores Nefertiti's exceptional influence, challenging traditional views of Egyptian queenship and highlighting the dynastic imperatives that may have necessitated female rule amid a lack of adult male heirs.[1]Counterarguments and Alternative Explanations

Scholars have raised several objections to the hypothesis of Nefertiti assuming coregency with Akhenaten or succeeding him as pharaoh under names such as Neferneferuaten or Smenkhkare, emphasizing the scarcity of direct epigraphic or iconographic evidence linking her to full royal titulary. No inscriptions record a coronation ceremony or the adoption of traditional pharaonic epithets by Nefertiti, and her depictions alongside Akhenaten, while prominent, consistently portray her in consort roles rather than as an equal sovereign with independent administrative authority. Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley argues that Nefertiti's elevated status during Akhenaten's reign (c. 1353–1336 BCE) was unprecedented for a non-royal woman but fell short of pharaonic rule, as her influence appears tied symbolically to her husband's Atenist reforms rather than institutional power.[37] [18] Critics of the coregency theory, including James P. Allen, contend that similarities between Nefertiti's epithets (e.g., "Neferneferuaten-Nefertiti") and the throne name Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten are circumstantial and do not override the absence of overlapping reign dates or joint monuments post-year 12 of Akhenaten's rule (c. 1338 BCE). Allen differentiates Neferneferuaten as a distinct successor figure, potentially female but separate from Smenkhkare, whose male-associated depictions and brief reign (c. 1335 BCE) suggest a different individual, possibly Akhenaten's son or a Mitannian prince, rather than Nefertiti adopting androgynous regalia. The scholarly consensus views Nefertiti's religious prominence in Aten worship as innovative but not indicative of co-rule, attributing such interpretations to modern projections onto ambiguous Amarna art styles that elongated female forms to mimic Akhenaten's.[38] [18] Alternative explanations for Nefertiti's vanishing from records after year 12 prioritize her likely death over political ascension, supported by the abrupt cessation of dated attestations amid Akhenaten's continued sole rule until approximately 1336 BCE. Archaeological analyses propose natural causes, such as a plague documented in the region during the late Amarna Period, or age-related decline, given her estimated birth around 1370 BCE and multiple childbirths (at least six daughters). Others suggest disgrace or exile following a family tragedy, like the death of daughter Meketaten (c. year 10–11), which some scenes interpret as childbirth-related, potentially eroding her standing in the Aten cult's emphasis on royal vitality. No burial has been confirmed, but the unfinished Royal Tomb at Amarna (WV22) shows preparations consistent with an interrupted interment for a queen, not a pharaoh's sarcophagus. These views align with the direct succession of Tutankhamun (c. 1332–1323 BCE), Nefertiti's probable stepson, without intermediary female rule, as non-royal or female pharaohs faced legitimacy barriers in the 18th Dynasty's patriarchal norms.[39] [17] [37]Death, Mummy, and Burial Debates

Estimated Timeline and Cause of Death Theories

Nefertiti's final confirmed depictions alongside Akhenaten appear in scenes from the 12th regnal year, including boundary stelae at Akhetaten (Amarna) showing the royal family receiving tribute, dated to the second month of that year.[40] These represent her last major artistic attestations as chief queen, after which she fades from prominent royal inscriptions, coinciding with the rise of figures like Smenkhkare.[41] Akhenaten's reign, conventionally dated circa 1353–1336 BCE, places this period around 1341 BCE, with her death theorized to follow soon after, potentially by year 14, based on the absence of subsequent references in official records. A quarry graffito from year 16 of Akhenaten's reign, discovered in the wadi between Akhetaten and Hatnub, names Nefertiti explicitly as queen, indicating she survived at least four years beyond her year 12 appearances and remained active during the later phase of the reign.[42] This evidence challenges earlier assumptions of an early death, supporting theories that she lived until approximately 1338–1336 BCE, possibly transitioning to a co-regency or advisory role before Akhenaten's demise.[43] However, the graffito's interpretation remains debated, as it lacks context on her status or location, and no further attestations confirm her survival into the post-Akhenaten era. The cause of Nefertiti's death remains unknown, with no contemporary Egyptian records or archaeological evidence providing direct insight, such as autopsy details or tomb inscriptions linking to specific ailments.[13] Speculative hypotheses, drawn from the timing of family losses like the death of daughter Meketaten around years 10–12 (possibly from complications of childbirth), suggest natural causes such as illness or age-related decline, given Nefertiti's estimated age of 30–35 at disappearance; yet these lack empirical support and rely on circumstantial parallels rather than forensic data. Theories of violent ends, including assassination or ritual sacrifice tied to Atenism's collapse, appear in non-scholarly speculation but find no backing in material evidence, underscoring the limitations of indirect historical reconstruction.[45] Overall, causal attributions prioritize empirical voids over unsubstantiated narratives, with burial practices potentially obscuring further clues due to Amarna's later desecration.KV21B Mummy Analysis and DNA Evidence

The tomb KV21, located in the Valley of the Kings, was excavated in 1906 by Edward Ayrton, yielding two unidentified female mummies designated KV21A and KV21B. KV21A, measuring approximately 1.62 meters in length and estimated to be no older than 25 years at death, was analyzed via DNA in a 2010 study led by Zahi Hawass, which confirmed her as the biological mother of the two female fetuses found in Tutankhamun's tomb, implying she is likely Ankhesenamun, Tutankhamun's principal wife and daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti.[46][47] KV21B, the older mummy, exhibited partial DNA matching the mitochondrial haplotype (type K) prevalent in the 18th Dynasty royal family, including Amenhotep III, Tiye, Akhenaten, and Tutankhamun, positioning her genetically as a close relative, potentially the paternal grandmother of the fetuses or another maternal figure in the lineage.[46] Subsequent CT scans of KV21B, conducted under Hawass's direction, indicated an age at death exceeding 40 years, with skeletal and cranial features—including a prominent chin and elongated skull—deemed compatible with artistic depictions of Nefertiti, prompting Hawass to propose in 2022 that KV21B represents Nefertiti's remains.[46][48] This hypothesis relies on morphological analysis rather than conclusive genetic linkage, as Nefertiti's presumed non-royal parentage (likely daughter of the noble Ay and not a product of sibling marriage) would predict a mitochondrial DNA profile distinct from the royal haplotype observed in KV21B, raising questions about compatibility.[49][50] Further DNA sampling from KV21B and comparative analysis with presumed Akhenaten remains (KV55 mummy) were initiated by Hawass's team in 2022, aiming to verify maternity links through shared nuclear DNA with Nefertiti's attested daughters, such as Meritaten or Ankhesenamun; however, as of late 2025, no definitive results confirming Nefertiti's identity have been published, with ongoing efforts described as preliminary.[48][51] A 2021 meta-analysis of 18th Dynasty mummy identifications highlighted persistent ambiguities in such assignments, attributing challenges to degraded samples, limited reference genomes, and interpretive biases in linking morphology to historical portraits.[47] Alternative identifications for KV21B include Tiye or another royal consort, consistent with the shared mtDNA but conflicting with age estimates and burial context.[46]Tomb Searches and Recent Archaeological Claims

Archaeological efforts to locate Nefertiti's tomb have spanned over a century, beginning with excavations at Amarna in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, where rock-cut tombs of Amarna royals were identified but yielded no definitive burial for the queen.[52] The Amarna Royal Tombs Project, led by Nicholas Reeves, continued surveys in the area during the 2010s, mapping potential sites but uncovering no intact royal interment attributable to Nefertiti.[53] These searches emphasized Amarna as a likely burial locale due to its association with Akhenaten's reign, though post-Amarna royal reburials in the Valley of the Kings have complicated attributions.[54] A prominent modern hypothesis emerged in 2015 when Reeves analyzed high-resolution scans of Tutankhamun's tomb (KV62), proposing that painted walls concealed doorways to an antechamber and burial chamber originally intended for Nefertiti, with Tutankhamun's interment adapting an existing structure. Reeves cited linear anomalies in the scans, interpreted as plastered-over tomb entrances, and argued that the tomb's unusual layout—entered via what would be another burial's antechamber—supported this reconfiguration during the transition from Amarna to traditional Theban practices.[55] Initial ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys in September 2015 detected voids behind the north and west walls, fueling speculation of an undisturbed royal tomb.[56] Subsequent investigations largely refuted the hidden-chamber theory. A 2016 GPR scan by Japanese and Egyptian teams identified possible organic material in voids but confirmed no accessible chambers or doorways, with Egyptian Antiquities Minister Mamdouh el-Damaty stating the data showed no evidence of additional spaces.[57] Further thermal imaging and GPR in 2018, the third such effort, revealed natural fissures rather than man-made structures, leading researchers to conclude KV62 contained no hidden annexes.[58] Egyptologist Zahi Hawass, who has advocated for Amarna as Nefertiti's burial site based on historical continuity with Akhenaten's monuments, dismissed the KV62 claims, asserting scans demonstrated the tomb's integrity as Tutankhamun's alone.[59] Recent claims persist amid ongoing excavations. In 2022, Hawass announced investigations into a potential Nefertiti mummy from an Amarna-period context, expressing confidence in its identification pending DNA analysis, though he maintained her tomb lay in Amarna's royal wadi rather than the Valley of the Kings.[60] By late 2024, Hawass anticipated unveiling Nefertiti's mummy in 2025, alongside clarifications on Tutankhamun's death, but as of October 2025, no such confirmation has materialized, with prior CT scans disproving earlier mummy attributions.[61] Alternative theories, including a Valley of the Queens location, draw on patterns of 18th Dynasty queenly burials but lack empirical support from ground surveys.[62] These efforts highlight persistent challenges in distinguishing hyped anomalies from verifiable architecture, with non-invasive scans often yielding inconclusive or natural features misinterpreted as artificial.[63]Diplomatic Context

Amarna Letters and Hittite Correspondence

The Amarna Letters comprise approximately 382 clay tablets inscribed in Akkadian cuneiform, unearthed in 1887 at Tell el-Amarna (ancient Akhetaten), forming the primary diplomatic archive of the Egyptian New Kingdom's international relations during the late reign of Amenhotep III and the rule of Akhenaten (c. 1353–1336 BC).[64] These documents, mostly incoming missives to the pharaoh, detail exchanges with Great Kings of Babylon, Assyria, Mitanni, and vassal states in Canaan and Syria, covering topics such as royal marriages, gold shipments, military support against rebels, and border disputes.[64] The letters reveal Egypt's weakened grip on its Levantine territories amid internal religious upheavals under Akhenaten, with frequent pleas from local rulers like Abdi-Heba of Jerusalem for intervention against invaders, including Hittite-aligned forces.[65] Direct correspondence from the Hittite kingdom of Hatti is sparse in the Amarna corpus, limited to just four letters that underscore the era's cautious diplomacy between the two powers.[66] These missives, likely from Hittite kings such as Tudhaliya the Younger or early Suppiluliuma I, address routine matters like the return of fugitive laborers or messengers, but they also hint at underlying tensions as Hatti consolidated control over northern Syria, encroaching on Egyptian influence without overt conflict during Akhenaten's lifetime.[66] Indirect references to Hittite activities appear more prominently in letters from Egyptian vassals and rivals like Mitanni's Tushratta (EA 17–29), who accused Hatti of aggressive expansion and appealed for Egyptian aid, exposing the fragility of the regional balance.[64] Subsequent Hittite-Egyptian correspondence, preserved in the royal archives at Hattusa (modern Boğazköy), dates to the immediate post-Amarna transition under Suppiluliuma I (c. 1344–1322 BC) and illuminates a shift toward more direct engagement amid Egyptian instability. Key among these are reports of Hittite military campaigns in Syria, including the conquest of Egyptian-allied territories like Nuhašše and Qadesh around 1340–1330 BC, which exploited the pharaoh's apparent neglect of foreign affairs.[66] A pivotal exchange involves a letter from an Egyptian royal woman (termed dakhamunzu, or "king's wife") to Suppiluliuma, announcing the death of "Nimmureya" (likely Naphurureya, a throne name for Tutankhamun or a predecessor) without an heir and proposing marriage to a Hittite prince to secure the throne; this prompted the dispatch of Zannanza, who was assassinated en route, straining relations and contributing to later conflicts like the Battle of Kadesh.[67] Additional Hittite texts, such as prayers by Mursili II (c. 1321–1295 BC), reference Egyptian envoys bearing ominous omens and plagues transmitted via diplomatic gifts, linking the correspondence to broader causal chains of disease and retribution in Anatolia. These archives, excavated in the early 20th century, provide a Hittite perspective contrasting the Egyptocentric Amarna record, emphasizing Hatti's opportunistic gains during Egypt's dynastic turmoil.Implications for Nefertiti's Involvement

![Nefertiti in a smiting scene on a boat, symbolizing her authority in state and potentially military-diplomatic matters][float-right] The Amarna Letters, an archive of approximately 382 clay tablets documenting diplomatic exchanges during Akhenaten's reign circa 1353–1336 BCE, contain no references to Nefertiti.[68] This absence stands in contrast to the multiple mentions of her mother-in-law, Queen Tiye, who is addressed directly in letters from foreign rulers and appears to have mediated diplomatic relations.[69] Scholars interpret this omission as potentially indicating that surviving correspondence focused on established channels involving Tiye, or that documents mentioning Nefertiti were lost or excluded from the archive; it does not preclude her indirect influence through Akhenaten's policies.[69] Nefertiti's elevated status, evidenced by her unique titles such as "Lady of All Women" and depictions equating her with the pharaoh in Atenist worship, implies participation in courtly audiences and rituals that hosted foreign envoys. Reliefs portray her alongside Akhenaten receiving tribute from vassals, a motif underscoring the royal couple's joint oversight of empire maintenance amid threats from powers like the Mitanni and Hittites documented in the letters. Her prominence in such iconography suggests a symbolic, if not operational, role in projecting Egyptian hegemony, which underpinned diplomatic leverage.[4] Post-Akhenaten Hittite records from Suppiluliuma I's reign describe an Egyptian queen—unnamed and claiming widowhood without a son—requesting a Hittite prince for marriage to assume the throne, circa 1330 BCE. A hypothesis identifies this figure as Nefertiti, ruling as the female pharaoh Neferneferuaten, seeking foreign alliance to counter domestic instability after Akhenaten's death and the brief Smenkhkare interlude. This view posits her diplomatic initiative as an attempt to preserve Atenist rule or secure power transition, supported by her attested coregency evidence but challenged by chronological mismatches and the traditional attribution to Ankhesenamun after Tutankhamun's death.[70][71] The theory remains speculative, lacking explicit name confirmation, and highlights debates over Nefertiti's survival beyond year 12 of Akhenaten's reign.[70]Legacy and Historical Assessment

Key Artifacts and Their Authenticity