Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Newborn screening

View on Wikipedia

| Newborn screening | |

|---|---|

| |

| MeSH | D015997 |

| MedlinePlus | 007257 |

Newborn screening (NBS) is a public health program of screening in infants shortly after birth for conditions that are treatable, but not clinically evident in the newborn period. The goal is to identify infants at risk for these conditions early enough to confirm the diagnosis and provide intervention that will alter the clinical course of the disease and prevent or ameliorate the clinical manifestations. NBS started with the discovery that the amino acid disorder phenylketonuria (PKU) could be treated by dietary adjustment, and that early intervention was required for the best outcome. Infants with PKU appear normal at birth, but are unable to metabolize the essential amino acid phenylalanine, resulting in irreversible intellectual disability. In the 1960s, Robert Guthrie developed a simple method using a bacterial inhibition assay that could detect high levels of phenylalanine in blood shortly after a baby was born. Guthrie also pioneered the collection of blood on filter paper which could be easily transported, recognizing the need for a simple system if the screening was going to be done on a large scale. Newborn screening around the world is still done using similar filter paper. NBS was first introduced as a public health program in the United States in the early 1960s, and has expanded to countries around the world.

Screening programs are often run by state or national governing bodies with the goal of screening all infants born in the jurisdiction for a defined panel of treatable disorders. The number of diseases screened for is set by each jurisdiction, and can vary greatly. Most NBS tests are done by measuring metabolites or enzyme activity in whole blood samples collected on filter paper. Bedside tests for hearing loss using automated auditory brainstem response and congenital heart defects using pulse oximetry are included in some NBS programs. Infants who screen positive undergo further testing to determine if they are truly affected with a disease or if the test result was a false positive. Follow-up testing is typically coordinated between geneticists and the infant's pediatrician or primary care physician.

History

[edit]Robert Guthrie is given much of the credit for pioneering the earliest screening for phenylketonuria in the late 1960s using a bacterial inhibition assay (BIA) to measure phenylalanine levels in blood samples obtained by pricking a newborn baby's heel on the second day of life on filter paper.[1] Congenital hypothyroidism was the second disease widely added in the 1970s.[2] Guthrie and colleagues also developed bacterial inhibition assays for the detection of maple syrup urine disease and classic galactosemia.[3] The development of tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) screening in the early 1990s led to a large expansion of potentially detectable congenital metabolic diseases that can be identified by characteristic patterns of amino acids and acylcarnitines.[4] In many regions, Guthrie's BIA has been replaced by MS/MS profiles, however the filter paper he developed is still used worldwide, and has allowed for the screening of millions of infants around the world each year.[5]

In the United States, the American College of Medical Genetics recommended a uniform panel of diseases that all infants born in every state should be screened for. They also developed an evidence-based review process for the addition of conditions in the future. The implementation of this panel across the United States meant all babies born would be screened for the same number of conditions. This recommendation is not binding for individual states, and some states may screen for disorders that are not included on this list of recommended disorders. Prior to this, babies born in different states had received different levels of screening. On April 24, 2008, President George W. Bush signed into law the Newborn Screening Saves Lives Act of 2007. This act was enacted to increase awareness among parents, health professionals, and the public on testing newborns to identify certain disorders. It also sought to improve, expand, and enhance current newborn screening programs at the state level.[citation needed]

Inclusion of disorders

[edit]Newborn screening programs initially used screening criteria based largely on criteria established by JMG Wilson and F. Jungner in 1968.[6] Although not specifically about newborn population screening programs, their publication, Principles and practice of screening for disease proposed ten criteria that screening programs should meet before being used as a public health measure. Newborn screening programs are administered in each jurisdiction, with additions and removals from the panel typically reviewed by a panel of experts. The four criteria from the publication that were relied upon when making decisions for early newborn screening programs were: [citation needed]

- having an acceptable treatment protocol in place that changes the outcome for patients diagnosed early with the disease

- an understanding of the condition's natural history

- an understanding about who will be treated as a patient

- a screening test that is reliable for both affected and unaffected patients and is acceptable to the public[7]

As diagnostic techniques have progressed, debates have arisen as to how screening programs should adapt. Tandem mass spectrometry has greatly expanded the potential number of diseases that can be detected, even without satisfying all of the other criteria used for making screening decisions.[7][8] Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a disease that has been added to screening programs in several jurisdictions around the world, despite the lack of evidence as to whether early detection improves the clinical outcome for a patient.[7]

Targeted disorders

[edit]Newborn screening is intended as a public health program to identify infants with treatable conditions before they present clinically, or suffer irreversible damage. Phenylketonuria (PKU) was the first disorder targeted for newborn screening, being implemented in a small number of hospitals and quickly expanding across the United States and the rest of the world.[9] After the success of newborn screening for PKU (39 infants were identified and treated in the first two years of screening, with no false negative results), Guthrie and others looked for other disorders that could be identified and treated in infants, eventually developing bacterial inhibition assays to identify classic galactosemia and maple syrup urine disease.[9][10]

Newborn screening has expanded since the introduction of PKU testing in the 1960s, but can vary greatly between countries. In 2011, the United States screened for 54 conditions, Germany for 12, the United Kingdom for 2 (PKU and medium chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MCADD)), while France and Hong Kong only screened for one condition (PKU and congenital hypothyroidism, respectively).[11] The conditions included in newborn screening programs around the world vary greatly, based on the legal requirements for screening programs, prevalence of certain diseases within a population, political pressure, and the availability of resources for both testing and follow-up of identified patients.[citation needed]

Congenital Disorders of Amino Acid Metabolism

[edit]Newborn screening originated with an amino acid disorder, phenylketonuria (PKU), which can be easily treated by dietary modifications, but causes severe Intellectual disability if not identified and treated early. Robert Guthrie introduced the newborn screening test for PKU in the early 1960s.[12] With the knowledge that PKU could be detected before symptoms were evident, and treatment initiated, screening was quickly adopted around the world. Ireland was the first country in the world to introduce a nationwide screening programme in February 1966,[13] Austria started screening the same year[14] and England in 1968.[15]

Other congenital disorders of amino acid metabolism tested for on the newborn screening include Tyrosinemia and Maple Syrup Urine Disorder.[citation needed]

Fatty acid oxidation disorders

[edit]With the advent of tandem mass spectrometry as a screening tool, several fatty acid oxidation disorders were targeted for inclusion in newborn screening programs. Medium chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MCADD), which had been implicated in several cases of sudden infant death syndrome[16][17][18] was one of the first conditions targeted for inclusion. MCADD was the first condition added when the United Kingdom expanded their screening program from PKU only.[11] Population based studies in Germany, the United States and Australia put the combined incidence of fatty acid oxidation disorders at 1:9300 among Caucasians. The United States screens for all known fatty acid oxidation disorders, either as primary or secondary targets, while other countries screen for a subset of these.[19]

The introduction of screening for fatty acid oxidation disorders has been shown to have reduced morbidity and mortality associated with the conditions, particularly MCADD. An Australian study found a 74% reduction in episodes of severe metabolic decompensation or death among individuals identified by newborn screening as having MCADD versus those who presented clinically prior to screening. Studies in the Netherlands and United Kingdom found improvements in outcome at a reduced cost when infants were identified before presenting clinically.[19]

Newborn screening programs have also expanded the information base available about some rare conditions. Prior to its inclusion in newborn screening, short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (SCADD) was thought to be life-threatening. Most patients identified via newborn screening as having this enzyme deficiency were asymptomatic, to the extent that SCADD was removed from screening panels in a number of regions. Without the cohort of patients identified by newborn screening, this clinical phenotype would likely not have been identified.[19]

Endocrinopathies

[edit]The most commonly included disorders of the endocrine system are congenital hypothyroidism (CH) and congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH).[20] Testing for both disorders can be done using blood samples collected on the standard newborn screening card. Screening for CH is done by measuring thyroxin (T4), thyrotropin (TSH) or a combination of both analytes. Elevated 17α-hydroxyprogesterone (17α-OHP) is the primary marker used when screening for CAH, most commonly done using enzyme-linked immunosorbant assays, with many programs using a second tier tandem mass spectrometry test to reduce the number of false positive results.[20] Careful analysis of screening results for CAH may also identify cases of congenital adrenal hypoplasia, which presents with extremely low levels of 17α-OHP.[20] When the immunoassay method is utilized as a screening method for quantifying 17α-OHP in dried blood spots, it exhibits a significant rate of false positive results. As per the clinical practice guideline issued by the Endocrine Society in 2018, employing LC-MS/MS to measure 17α-OHP and other adrenal steroid hormones (such as 21-deoxycortisol and androstenedione) is recommended as a supplementary screening approach to enhance the accuracy of positive predictions.[21]

CH was added to many newborn screening programs in the 1970s, often as the second condition included after PKU. The most common cause of CH is dysgenesis of the thyroid gland After many years of newborn screening, the incidence of CH worldwide had been estimated at 1:3600 births, with no obvious increases in specific ethnic groups. Recent data from certain regions have shown an increase, with New York reporting an incidence of 1:1700. Reasons for the apparent increase in incidence have been studied, but no explanation has been found.[20]

Classic CAH, the disorder targeted by newborn screening programs, is caused by a deficiency of the enzyme steroid 21-hydroxylase and comes in two forms – simple virilizing and a salt-wasting form. The incidence of CAH can vary greatly between populations. The highest reported incidence rates are among the Yupic Eskimos of Alaska (1:280) and on the French island of Réunion (1:2100).[20]

Hemoglobinopathies

[edit]

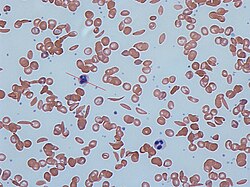

Any condition that results in the production of abnormal hemoglobin is included under the broad category of hemoglobinopathies. Worldwide, it is estimated that 7% of the population may carry a hemoglobinopathy with clinical significance.[22] The most well known condition in this group is sickle cell disease.[22] Newborn screening for a large number of hemoglobinopathies is done by detecting abnormal patterns using isoelectric focusing, which can detect many different types of abnormal hemoglobins.[22] In the United States, newborn screening for sickle cell disease was recommended for all infants in 1987, however it was not implemented in all 50 states until 2006.[22]

Early identification of individuals with sickle cell disease and other hemoglobinopathies allows treatment to be initiated in a timely fashion. Penicillin has been used in children with sickle cell disease, and blood transfusions are used for patients identified with severe thalassemia.[22]

Organic acidemias

[edit]Most jurisdictions did not start screening for any of the organic acidemias before tandem mass spectrometry significantly expanded the list of disorders detectable by newborn screening. Quebec has run a voluntary second-tier screening program since 1971 using urine samples collected at three weeks of age to screen for an expanded list of organic acidemias using a thin layer chromatography method.[23] Newborn screening using tandem mass spectrometry can detect several organic acidemias, including propionic acidemia, methylmalonic acidemia and isovaleric acidemia.[citation needed]

Cystic fibrosis

[edit]Cystic fibrosis (CF) was first added to newborn screening programs in New Zealand and regions of Australia in 1981, by measuring immunoreactive trypsinogen (IRT) in dried blood spots.[24] After the CFTR gene was identified, Australia introduced a two tier testing program to reduce the number of false positives. Samples with an elevated IRT value were then analyzed with molecular methods to identify the presence of disease causing mutations before being reported back to parents and health care providers.[25] CF is included in the core panel of conditions recommended for inclusion in all 50 states, Texas was the last state to implement their screening program for CF in 2010.[26] Alberta was the first Canadian province to implement CF screening in 2007.[27] Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Prince Edward Island do not include CF in their screening programs.[28] The United Kingdom as well as many European Union countries screen for CF as well.[28] Switzerland is one of the latest countries to add CF to their newborn screening menu, doing so in January 2011.[24]

Urea cycle disorders

[edit]Disorders of the distal urea cycle, such as citrullinemia, argininosuccinic aciduria and argininemia are included in newborn screening programs in many jurisdictions that using tandem mass spectrometry to identify key amino acids. Proximal urea cycle defects, such as ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency and carbamoyl phosphate synthetase deficiency are not included in newborn screening panels because they are not reliably detected using current technology, and also because severely affected infants will present with clinical symptoms before newborn screening results are available. Some regions claim to screen for HHH syndrome (hyperammonemia, hyperornithinemia, homocitrullinuria) based on the detection of elevated ornithine levels in the newborn screening dried blood spot, but other sources have shown that affected individuals do not have elevated ornithine at birth.[29]

Lysosomal storage disorders

[edit]Lysosomal storage disorders are not included in newborn screening programs with high frequency. As a group, they are heterogenous, with screening only being feasible for a small fraction of the approximately 40 identified disorders. The arguments for their inclusion in newborn screening programs center around the advantage of early treatment (when treatment is available), avoiding a diagnostic odyssey for families and providing information for family planning to couples who have an affected child.[30] The arguments against including these disorders, as a group or individually center around the difficulties with reliably identifying individuals who will be affected with a severe form of the disorder, the relatively unproven nature of the treatment methods, and the high cost / high risk associated with some treatment options.[30]

New York State started a pilot study to screen for Krabbe disease in 2006, largely due to the efforts of Jim Kelly, whose son, Hunter, was affected with the disease.[31] A pilot screening program for four lysosomal storage diseases (Gaucher disease, Pompe disease, Fabry disease and Niemann-Pick disease was undertaken using anonymised dried blood spots was completed in Austria in 2010. Their data showed an increased incidence from what was expected in the population, and also a number of late onset forms of disease, which are not typically the target for newborn screening programs.[32]

Hearing loss

[edit]Undiagnosed hearing loss in a child can have serious effects on many developmental areas, including language, social interactions, emotions, cognitive ability, academic performance and vocational skills, any combination of which can have negative impacts on the quality of life.[33] The serious impacts of a late diagnosis, combined with the high incidence (estimated at 1 - 3 per 1000 live births, and as high as 4% for neonatal intensive care unit patients) have been the driving forces behind screening programs designed to identify infants with hearing loss as early as possible. Early identification allows these patients and their families to access the necessary resources to help them maximize their developmental outcomes.[33]

Newborn hearing testing is done at the bedside using transiently evoked otoacoustic emissions, automated auditory brainstem responses, or a combination of both techniques. Hearing screening programs have found the initial testing to cost between $10.20 and $23.37 per baby, depending on the technology used.[33] As these are screening tests only, false positive results will occur. False positive results could be due to user error, a fussy baby, environmental noise in the testing room, or fluid or congestion in the outer/middle ear of the baby. A review of hearing screening programs found varied initial referral rates (screen positive results) from 0.6% to 16.7%. The highest overall incidence of hearing loss detection was 0.517%.[33] A significant proportion of screen positive infants were lost to follow-up before a diagnosis could be confirmed or ruled out in all screening programs.[33]

Congenital heart defects

[edit]In some cases, critical congenital heart defects (CCHD) are not identified by prenatal ultrasound or postnatal physical examination. Pulse oximetry has been recently added as a bedside screening test for CCHD[34] at 24 to 48 hours after birth. However, not all heart problems can be detected by this method, which relies only on blood oxygen levels.

When a baby tests positive, urgent subsequent examination, such as echocardiography, is undergone to determine the cause of low oxygen levels. Babies diagnosed with CCHD are then seen by cardiologists.[citation needed]

Severe combined immunodeficiency

[edit]Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) caused by T-cell deficiency is a disorder that was recently added to newborn screening programs in some regions of the United States. Wisconsin was the first state to add SCID to their mandatory screening panel in 2008, and it was recommended for inclusion in all states' panels in 2010. Since December 2018 all US states perform SCID screening.[35] As the first country in Europe, Norway started nationwide SCID screening January 2018.[36][37] Identification of infants with SCID is done by detecting T-cell receptor excision circles (TRECs) using real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). TRECs are decreased in infants affected with SCID.[38]

SCID has not been added to newborn screening in a wide scale for several reasons. It requires technology that is not currently used in most newborn screening labs, as PCR is not used for any other assays included in screening programs. Follow-up and treatment of affected infants also requires skilled immunologists, which may not be available in all regions. Treatment for SCID is a stem cell transplant, which cannot be done in all centers.[38]

Other conditions

[edit]Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is an X-linked disorder caused by defective production of dystrophin. Many jurisdictions around the world have screened for, or attempted to screen for DMD using elevated levels of creatine kinase measured in dried blood spots. Because universal newborn screening for DMD has not been undertaken, affected individuals often have a significant delay in diagnosis. As treatment options for DMD become more and more effective, interest in adding a newborn screening test increases. At various times since 1978, DMD has been included (often as a pilot study on a small subset of the population) in newborn screening programs in Edinburgh, Germany, Canada, France, Wales, Cyprus, Belgium and the United States. In 2012, Belgium was the only country that continued to screen for DMD using creatine kinase levels.[39]

As treatments improve, newborn screening becomes a possibility for disorders that could benefit from early intervention, but none was previously available. Adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), a peroxisomal disease that has a variable clinical presentation is one of the disorders that has become a target for those seeking to identify patients early. ALD can present in several different forms, some of which do not present until adulthood, making it a difficult choice for countries to add to screening programs. The most successful treatment option is a stem cell transplant, a procedure that carries a significant risk.[40]

Techniques

[edit]Sample collection

[edit]Newborn screening tests are most commonly done from whole blood samples collected on specially designed filter paper, originally designed by Robert Guthrie. The filter paper is often attached to a form containing required information about the infant and parents. This includes date and time of birth, date and time of sample collection, the infant's weight and gestational age. The form will also have information about whether the baby has had a blood transfusion and any additional nutrition the baby may have received (total parenteral nutrition). Most newborn screening cards also include contact information for the infant's physician in cases where follow up screening or treatment is needed. The Canadian province of Quebec performs newborn screening on whole blood samples collected as in most other jurisdictions, and also runs a voluntary urine screening program where parents collect a sample at 21 days of age and submit it to a provincial laboratory for an additional panel of conditions.[41][23]

Newborn screening samples are collected from the infant between 24 hours and 7 days after birth, and it is recommended that the infant has fed at least once. Individual jurisdictions will often have more specific requirements, with some states accepting samples collected at 12 hours, and others recommending to wait until 48 hours of life or later. Each laboratory will have its own criteria on when a sample is acceptable, or if another would need to be collected. Samples can be collected at the hospital, or by midwives. Samples are transported daily to the laboratory responsible for testing. In the United States and Canada, newborn screening is mandatory, with an option for parents to opt out of the screening in writing if they desire. In many regions, NBS is mandatory, with an option for parents to opt out in writing if they choose not to have their infant screened.[42] In most of Europe, newborn screening is done with the consent of the parents. Proponents of mandatory screening claim that the test is for the benefit of the child, and that parents should not be able to opt out on their behalf. In regions that favour informed consent for the procedure, they report no increase in costs, no decrease in the number of children screened and no cases of included diseases in children who did not undergo screening.[43]

Laboratory testing

[edit]Because newborn screening programs test for a number of conditions, a number of laboratorial methodologies are used, as well as bedside testing for hearing loss using evoked auditory potentials[33] and congenital heart defects using pulse oximetry.[34] In the early 1960s Newborn screening started out using simple bacterial inhibition assays to screen for a single disorder, starting with phenylketonuria.[12] With this testing methodology, newborn screening required one test to detect one condition. As mass spectrometry became more widely available, the technology allowed rapid determination of a number of acylcarnitines and amino acids from a single dried blood spot. This increased the number of conditions that could be detected by newborn screening. Enzyme assays are used to screen for galactosemia and biotinidase deficiency. Immunoassays measure thyroid hormones for the diagnosis of congenital hypothyroidism and 17α-hydroxyprogesterone for the diagnosis of congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Molecular techniques are used for the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis and severe combined immunodeficiency.[citation needed]

As of 2023, numerous initiatives using next generation sequencing (NGS) have been announced worldwide including the Genomic Uniform-screening Against Rare Diseases in All Newborns (GUARDIAN study), BeginNGS and Early Check in the USA, BabyScreen+ in Australia, Generation Study by Genomics England,[44] and Screen4Care,[45] Baby Detect in Belgium[46] and PERIGENOMED in France.[47] In a 2023 survey of 14 European newborn screening programs, there was one pan-European research study with 2 pilot trials planned in Germany (NEW_LIVES)[48] and Italy, the others included three initiatives in Italy, three in the Netherlands, two in Spain, one in Belgium, one in England, one in Germany, one in Greece[49] and one in France. Of the 14 initiatives, 11 selected a single NGS approach for their studies: 6 initiatives planned to use only whole genome sequencing (WGS) as a first-tier test for NBS, including one also testing parents using whole exome sequencing (WES) to facilitate filtering variants, 3 initiatives use classical NGS gene panels, 2 initiatives will be using WES and 2 initiatives will use a mixed approach: one comparing WES and Whole genome sequencing (WGS) and one comparing WES, WGS, and classical NGS. gene panels.[47]

Reporting results

[edit]The goal is to report the results within a short period of time. If screens are normal, a paper report is sent to the submitting hospital and parents rarely hear about it. If an abnormality is detected, employees of the agency, usually nurses, begin to try to reach the physician, hospital, and/or nursery by telephone. They are persistent until they can arrange an evaluation of the infant by an appropriate specialist physician (depending on the disease). The specialist will attempt to confirm the diagnosis by repeating the tests by a different method or laboratory, or by performing other corroboratory or disproving tests. The confirmatory test varies depending on the positive results on the initial screen. Confirmatory testing can include analyte specific assays to confirm any elevations detected, functional studies to determine enzyme activity, and genetic testing to identify disease-causing mutations. In some cases, a positive newborn screen can also trigger testing on other family members, such as siblings who did not undergo newborn screening for the same condition or the baby's mother, as some maternal conditions can be identified through results on the baby's newborn screen. Depending on the likelihood of the diagnosis and the risk of delay, the specialist will initiate treatment and provide information to the family. Performance of the program is reviewed regularly and strenuous efforts are made to maintain a system that catches every infant with these diagnoses. Guidelines for newborn screening and follow up have been published by the American Academy of Pediatrics[50] and the American College of Medical Genetics.[51]

Laboratory performance

[edit]Newborn screening programs participate in quality control programs as in any other laboratory, with some notable exceptions. Much of the success of newborn screening programs is dependent on the filter paper used for the collection of the samples. Initial studies using Robert Guthrie's test for PKU reported high false positive rates that were attributed to a poorly selected type of filter paper.[52] This source of variation has been eliminated in most newborn screening programs through standardization of approved sources of filter paper for use in newborn screening programs. In most regions, the newborn screening card (which contains demographic information as well as attached filter paper for blood collection) is supplied by the organization carrying out the testing, to remove variations from this source.[52]

Society and culture

[edit]Controversy

[edit]Newborn screening tests have become a subject of political controversy in the last decade[clarification needed]. Lawsuits, media attention, and advocacy groups have surfaced a number of different, and possibly countervailing, positions on the use of screening tests. Some have asked for government mandates to widen the extent of the screening to find detectable and treatable birth defects. Others have opposed mandatory screening concerned that effective follow-up and treatment may not be available, or that false positive screening tests may cause harm to infants and their families. Others have learned that government agencies were often secretly storing the results in databases for future genetic research, often without consent of the parents nor limits on how the data could be used in the future [citation needed]. In the UK a campaign called the Newborn Screening Collaborative, 17 small rare disease organisations including Genetic Alliance UK, have joined together to raise awareness surrounding this issue and promote the positives of early diagnosis.[citation needed]

Increasing mandatory tests in California

[edit]Many rare diseases have not historically been tested for or testing that has been available has not been mandatory. One such disease is glutaric acidemia type I, a neurometabolic disease present in approximately 1 out of every 100,000 live births.[53] A short-term California testing pilot project in 2003 and 2004 demonstrated the cost of forgoing rare disease testing on newborns. While both Zachary Wyvill and Zachary Black were both born with the same disease during the pilot program, Wyvill's birth hospital tested only for four state-mandated diseases while Black was born at a hospital participating in the pilot program. Wyvill's disease went undetected for over six months during which irreversible damage occurred but Black's disease was treated with diet and vitamin supplements.[54] Both sets of parents became advocates for expanded neonatal testing and testified in favor of expanding tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) testing of newborns for rare diseases. By August, 2004, the California state budget law had passed requiring the use of tandem mass spectroscopy to test for more than 30 genetic illnesses and provided funding.[55] California now mandates newborn screening for all infants and tests for 80 congenital and genetic disorders.[56]

Government budgetary limitations

[edit]Instituting MS/MS screening often requires a sizable up front expenditure. When states choose to run their own programs the initial costs for equipment, training and new staff can be significant. Moreover, MS/MS gives only the screening result and not the confirmatory result. The same has to be further done by higher technologies or procedure like GC/MS[clarification needed], Enzyme Assays or DNA Tests. This in effect adds more cost burden and makes physicians lose precious time.[according to whom?] To avoid at least a portion of the up front costs, some states such as Mississippi have chosen to contract with private labs for expanded screening. Others have chosen to form Regional Partnerships sharing both costs and resources.[citation needed]

But for many states, screening has become an integrated part of the department of health which can not or will not be easily replaced. Thus the initial expenditures can be difficult for states with tight budgets to justify. Screening fees have also increased in recent years as health care costs rise and as more states add MS/MS screening to their programs. (See Report of Summation of Fees Charged for Newborn Screening, 2001–2005) Dollars spent for these programs may reduce resources available to other potentially lifesaving programs. It was recommended[by whom?] in 2006 that one disorder, Short Chain Acyl-coenzyme A Dehydrogenase Deficiency, or SCAD, be eliminated from screening programs, due to a "spurious association between SCAD and symptoms.[57] However, other[when?] studies suggested that perhaps expanded screening is cost effective (see ACMG report page 94-95[dead link] and articles published in Pediatrics[58]'.[59] Advocates are quick to point out studies such as these when trying to convince state legislatures to mandate expanded screening.[citation needed]

Decreasing mandatory tests

[edit]Expanded newborn screening is also opposed by among some health care providers, who are concerned that effective follow-up and treatment may not be available, that false positive screening tests may cause harm, and issues of informed consent.[60] A recent study by Genetic Alliance and partners suggests that communication between health care providers and parents may be key in minimizing the potential harm when a false positive test occurs. The results from this study also reveal that parents found newborn screening to be a beneficial and necessary tool to prevent treatable diseases.[61] To address the false positive issue, researchers from the University of Maryland, Baltimore and Genetic Alliance established a check-list to assist health care providers communicate with parents about a screen-positive result.[62]

Secret genetic research

[edit]Controversy has also erupted in some countries over collection and storage of blood or DNA samples by government agencies during the routine newborn blood screen.[citation needed]

In the United States, it was revealed that Texas had collected and stored blood and DNA samples on millions of newborns without the parents' knowledge or consent. These samples were then used by the state for genetic experiments and to set up a database to catalog all of the samples/newborns. As of December 2009[update], samples obtained without parents' consent between 2002 and 2009 were slated to be destroyed following the settlement of "a lawsuit filed by parents against the Texas Department of Health Services and Texas A&M; for secretly storing and doing research on newborn blood samples."[63]

A similar legal case was filed against the State of Minnesota. Over 1 million newborn bloodspot samples were destroyed in 2011 "when the state's Supreme Court found that storage and use of blood spots beyond newborn screening panels was in violation of the state's genetic privacy laws.".[citation needed] Nearly US$1 million was required to be paid by the state for the attorney's fees of the 21 families who advanced the lawsuit. An advocacy group that has taken a position against research on newborn blood screening data without parental consent is the Citizens' Council for Health Freedom, who take the position that newborn health screening for "a specific set of newborn genetic conditions" is a very different matter than storing the data or those DNA samples indefinitely to "use them for genetic research without parental knowledge or consent."[citation needed]

Bioethics

[edit]As additional tests are discussed for addition to the panels, issues arise. Many question whether the expanded testing still falls under the requirements necessary to justify the additional tests.[64] Many of the new diseases being tested for are rare and have no known treatment, while some of the diseases need not be treated until later in life.[64] This raises more issues, such as: if there is no available treatment for the disease should we test for it at all? And if we do, what do we tell the families of those with children bearing one of the untreatable diseases?[65] Studies show that the rarer the disease is and the more diseases being tested for, the more likely the tests are to produce false-positives.[66] This is an issue because the newborn period is a crucial time for the parents to bond with the child, and it has been noted that ten percent of parents whose children were diagnosed with a false-positive still worried that their child was fragile and/or sickly even though they were not, potentially preventing the parent-child bond forming as it would have otherwise.[65] As a result, some parents may begin to opt out of having their newborns screened. Many parents are also concerned about what happens with their infant's blood samples after screening. The samples were originally taken to test for preventable diseases, but with the advance in genomic sequencing technologies many samples are being kept for DNA identification and research,[64][65] increasing the possibility that more children will be opted out of newborn screening from parents who see the kept samples as a form of research done on their child.[64]

See also

[edit]- Euphenics – American molecular biologist (1925–2008)

- Prenatal testing – Testing for diseases or conditions in a fetus

References

[edit]- ^ Clague A, Thomas A (January 2002). "Neonatal biochemical screening for disease". Clinica Chimica Acta; International Journal of Clinical Chemistry. 315 (1–2): 99–110. doi:10.1016/S0009-8981(01)00716-1. PMID 11728413.

- ^ Klein AH, Agustin AV, Foley TP (July 1974). "Successful laboratory screening for congenital hypothyroidism". Lancet. 2 (7872): 77–79. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(74)91637-7. PMID 4137217.

- ^ Koch J (1997). Robert Guthrie: The PKU Story. Hope Publishing House. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-0-932727-91-6.

- ^ Chace DH, Kalas TA, Naylor EW (November 2003). "Use of tandem mass spectrometry for multianalyte screening of dried blood specimens from newborns". Clinical Chemistry. 49 (11): 1797–1817. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2003.022178. PMID 14578311.

- ^ Chace DH, Hannon WH (March 2016). "Filter Paper as a Blood Sample Collection Device for Newborn Screening". Clinical Chemistry. 62 (3): 423–425. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2015.252007. PMID 26797689.

- ^ Wilson JM, Jungner YG (October 1968). "[Principles and practice of mass screening for disease]". Boletin de la Oficina Sanitaria Panamericana. Pan American Sanitary Bureau. 65 (4): 281–393. PMID 4234760.

- ^ a b c Ross LF (April 2006). "Screening for conditions that do not meet the Wilson and Jungner criteria: the case of Duchenne muscular dystrophy". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 140 (8): 914–922. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.31165. PMID 16528755. S2CID 24612331.

- ^ Pollitt RJ (June 2009). "Newborn blood spot screening: new opportunities, old problems". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 32 (3): 395–399. doi:10.1007/s10545-009-9962-0. PMID 19412659. S2CID 41563580.

- ^ a b Gonzalez J, Willis MA (2009). "Robert Guthrie, MD, PhD: Clinical Chemistry/Microbiology". Laboratory Medicine. 40 (12): 748–749. doi:10.1309/LMD48N6BNZSXIPVH.

- ^ Koch J (1997). Robert Guthrie: The PKU Story. Hope Publishing House. p. x. ISBN 978-0-932727-91-6.

- ^ a b Lindner M, Gramer G, Haege G, Fang-Hoffmann J, Schwab KO, Tacke U, et al. (June 2011). "Efficacy and outcome of expanded newborn screening for metabolic diseases--report of 10 years from South-West Germany". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 6 44. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-6-44. PMC 3141366. PMID 21689452.

- ^ a b Mitchell JJ, Trakadis YJ, Scriver CR (August 2011). "Phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency". Genetics in Medicine. 13 (8): 697–707. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182141b48. PMID 21555948. S2CID 25921607.

- ^ Koch J (1997). Robert Guthrie--the PKU story : crusade against mental retardation. Pasadena, Calif.: Hope Pub. House. pp. 65–66. ISBN 0-932727-91-3. OCLC 36352725.

- ^ Kasper DC, Ratschmann R, Metz TF, Mechtler TP, Möslinger D, Konstantopoulou V, et al. (November 2010). "The national Austrian newborn screening program - eight years experience with mass spectrometry. past, present, and future goals". Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. 122 (21–22): 607–613. doi:10.1007/s00508-010-1457-3. PMID 20938748. S2CID 27643449.

- ^ Komrower GM, Sardharwalla IB, Fowler B, Bridge C (September 1979). "The Manchester regional screening programme: a 10-year exercise in patient and family care". British Medical Journal. 2 (6191): 635–638. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.6191.635. PMC 1596331. PMID 497752.

- ^ Yang Z, Lantz PE, Ibdah JA (December 2007). "Post-mortem analysis for two prevalent beta-oxidation mutations in sudden infant death". Pediatrics International. 49 (6): 883–887. doi:10.1111/j.1442-200X.2007.02478.x. PMID 18045290. S2CID 25455710.

- ^ Korman SH, Gutman A, Brooks R, Sinnathamby T, Gregersen N, Andresen BS (June 2004). "Homozygosity for a severe novel medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) mutation IVS3-1G > C that leads to introduction of a premature termination codon by complete missplicing of the MCAD mRNA and is associated with phenotypic diversity ranging from sudden neonatal death to asymptomatic status". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 82 (2): 121–129. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.03.002. PMID 15171999.

- ^ Gregersen N, Winter V, Jensen PK, Holmskov A, Kølvraa S, Andresen BS, et al. (January 1995). "Prenatal diagnosis of medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) deficiency in a family with a previous fatal case of sudden unexpected death in childhood". Prenatal Diagnosis. 15 (1): 82–86. doi:10.1002/pd.1970150118. PMID 7740006. S2CID 24295134.

- ^ a b c Lindner M, Hoffmann GF, Matern D (October 2010). "Newborn screening for disorders of fatty-acid oxidation: experience and recommendations from an expert meeting". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 33 (5): 521–526. doi:10.1007/s10545-010-9076-8. PMID 20373143. S2CID 1794910.

- ^ a b c d e Pass KA, Neto EC (December 2009). "Update: newborn screening for endocrinopathies". Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 38 (4): 827–837. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2009.08.005. PMID 19944295.

- ^ Mu D, Sun D, Qian X, Ma X, Qiu L, Cheng X, et al. (January 2024). "Steroid profiling in adrenal disease". Clinica Chimica Acta; International Journal of Clinical Chemistry. 553 117749. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2023.117749. PMID 38169194. S2CID 266721414.

- ^ a b c d e Benson JM, Therrell BL (April 2010). "History and current status of newborn screening for hemoglobinopathies". Seminars in Perinatology. 34 (2): 134–144. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2009.12.006. PMID 20207263.

- ^ a b "Newborn urine screening". Government of Quebec. Archived from the original on 2012-01-14. Retrieved 2012-08-16.

- ^ a b Barben J, Gallati S, Fingerhut R, Schoeni MH, Baumgartner MR, Torresani T (July 2012). "Retrospective analysis of stored dried blood spots from children with cystic fibrosis and matched controls to assess the performance of a proposed newborn screening protocol in Switzerland". Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. 11 (4): 332–336. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2012.01.001. PMID 22300503.

- ^ Sobczyńska-Tomaszewska A, Ołtarzewski M, Czerska K, Wertheim-Tysarowska K, Sands D, Walkowiak J, et al. (April 2013). "Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis: Polish 4 years' experience with CFTR sequencing strategy". European Journal of Human Genetics. 21 (4): 391–396. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2012.180. PMC 3598320. PMID 22892530.

- ^ Wagener JS, Zemanick ET, Sontag MK (June 2012). "Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 24 (3): 329–335. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e328353489a. PMID 22491493. S2CID 44562190.

- ^ Lilley M, Christian S, Hume S, Scott P, Montgomery M, Semple L, et al. (November 2010). "Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis in Alberta: Two years of experience". Paediatrics & Child Health. 15 (9): 590–594. doi:10.1093/pch/15.9.590. PMC 3009566. PMID 22043142.

- ^ a b "Cystic Fibrosis Canada Calls for CF Newborn Screening in Every Province—Early CF Detection Saves Lives". Cystic Fibrosis Canada. 2012-07-26. Archived from the original on 2013-10-14. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ Sokoro AA, Lepage J, Antonishyn N, McDonald R, Rockman-Greenberg C, Irvine J, et al. (December 2010). "Diagnosis and high incidence of hyperornithinemia-hyperammonemia-homocitrullinemia (HHH) syndrome in northern Saskatchewan". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 33 (Suppl 3): S275 – S281. doi:10.1007/s10545-010-9148-9. PMID 20574716. S2CID 955463.

- ^ a b Marsden D, Levy H (July 2010). "Newborn screening of lysosomal storage disorders". Clinical Chemistry. 56 (7): 1071–1079. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2009.141622. PMID 20489136.

- ^ Osorio S (2011-07-28). "Jim Kelly and Hunter's Hope families push for universal newborn screening". WBFO 88.7, Buffalo's NPR News Station.

- ^ Mechtler TP, Stary S, Metz TF, De Jesús VR, Greber-Platzer S, Pollak A, et al. (January 2012). "Neonatal screening for lysosomal storage disorders: feasibility and incidence from a nationwide study in Austria". Lancet. 379 (9813): 335–341. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61266-X. PMID 22133539. S2CID 23650785.

- ^ a b c d e f Papacharalampous GX, Nikolopoulos TP, Davilis DI, Xenellis IE, Korres SG (October 2011). "Universal newborn hearing screening, a revolutionary diagnosis of deafness: real benefits and limitations". European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 268 (10): 1399–1406. doi:10.1007/s00405-011-1672-1. PMID 21698417. S2CID 20647009.

- ^ a b Thangaratinam S, Brown K, Zamora J, Khan KS, Ewer AK (June 2012). "Pulse oximetry screening for critical congenital heart defects in asymptomatic newborn babies: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet. 379 (9835): 2459–2464. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60107-X. PMID 22554860. S2CID 19949842.

- ^ "All 50 States Now Screening Newborns for Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) | Immune Deficiency Foundation". primaryimmune.org. Archived from the original on 2019-09-05. Retrieved 2023-05-29.

- ^ "Norske barn blir de første i Europa som screenes for immunsvikt". 13 October 2017.

- ^ Puck JM (July 2018). "Lessons for Sequencing from the Addition of Severe Combined Immunodeficiency to Newborn Screening Panels". The Hastings Center Report. 48 (Suppl 2): S7 – S9. doi:10.1002/hast.875. PMC 6886663. PMID 30133735.

- ^ a b Chase NM, Verbsky JW, Routes JM (December 2010). "Newborn screening for T-cell deficiency". Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 10 (6): 521–525. doi:10.1097/ACI.0b013e32833fd6fe. PMID 20864885. S2CID 13506398.

- ^ "Newborn screening for DMD shows promise as an international model". Nationwide Children's Hospital. 2012-03-19. Archived from the original on 2015-10-15. Retrieved 2012-08-24.

- ^ Raymond GV, Jones RO, Moser AB (2007). "Newborn screening for adrenoleukodystrophy: implications for therapy". Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy. 11 (6): 381–384. doi:10.1007/BF03256261. PMID 18078355. S2CID 21323198.

- ^ "Newborn blood screening". Government of Quebec. Retrieved 2012-08-16.

- ^ Carmichael M (July 2011). "Newborn screening: a spot of trouble". Nature. 475 (7355): 156–158. doi:10.1038/475156a. PMID 21753828.

- ^ Nicholls SG (May 2012). "Proceduralisation, choice and parental reflections on decisions to accept newborn bloodspot screening". Journal of Medical Ethics. 38 (5): 299–303. doi:10.1136/medethics-2011-100040. PMID 22186830. S2CID 207009929.

- ^ "Newborn Genomes Programme". Genomics England. nd. Retrieved 2024-03-20.

- ^ "Screen4Care". screen4care.eu. Retrieved 2024-03-20.

- ^ "Baby Detect – Improve the newborn screening!". nd. Retrieved 2024-03-20.

- ^ a b Bros-Facer V, Taylor S, Patch C (2023-10-07). "Next-generation sequencing-based newborn screening initiatives in Europe: an overview". Rare Disease and Orphan Drugs Journal. 2 (4). doi:10.20517/rdodj.2023.26.

- ^ Universitätsklinikum Heidelberg (nd). "NEW_LIVES: Genomic Newborn Screening Programs". www.klinikum.uni-heidelberg.de. Retrieved 2024-03-20.

- ^ "Αρχική First steps". First Steps. Retrieved 2024-03-20.

- ^ American Academy of Pediatrics Newborn Screening Authoring Committee (January 2008). "Newborn screening expands: recommendations for pediatricians and medical homes--implications for the system". Pediatrics. 121 (1): 192–217. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-3021. PMID 18166575.

- ^ "ACMG NBS ACT Sheets". American College of Medical Genetics. Retrieved 2012-08-12.

- ^ a b De Jesús VR, Mei JV, Bell CJ, Hannon WH (April 2010). "Improving and assuring newborn screening laboratory quality worldwide: 30-year experience at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention". Seminars in Perinatology. 34 (2): 125–133. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2009.12.003. PMID 20207262.

- ^ Hoffmann G. "Glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency". Orphanet. The portal for rare diseases and orphan drugs. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ Waldholz M (17 June 2004). "Testing Fate: A Drop of Blood Saves One Baby; Another Falls Ill". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ Lynch A. "State to expand testing of newborns for genetic ills". San Jose Mercury News. No. 4 August 2004.

- ^ "Newborn Screening Program (NBS)". California Department of Public Health. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ Waisbren SE (August 2006). "Newborn screening for metabolic disorders". JAMA. 296 (8): 993–995. doi:10.1001/jama.296.8.993. PMID 16926360.

- ^ Schulze A, Lindner M, Kohlmüller D, Olgemöller K, Mayatepek E, Hoffmann GF (June 2003). "Expanded newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism by electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry: results, outcome, and implications". Pediatrics. 111 (6 Pt 1): 1399–1406. doi:10.1542/peds.111.6.1399. PMID 12777559.

- ^ Schoen EJ, Baker JC, Colby CJ, To TT (October 2002). "Cost-benefit analysis of universal tandem mass spectrometry for newborn screening". Pediatrics. 110 (4): 781–786. doi:10.1542/peds.110.4.781. PMID 12359795.

- ^ "Financial, Ethical, Legal, and Social Issues". Archived from the original on 2006-01-27. Retrieved 2006-01-24.

- ^ Schmidt JL, Castellanos-Brown K, Childress S, Bonhomme N, Oktay JS, Terry SF, et al. (January 2012). "The impact of false-positive newborn screening results on families: a qualitative study". Genetics in Medicine. 14 (1): 76–80. doi:10.1038/gim.2011.5. PMID 22237434.

- ^ "Checklist for communicating with parents about an out-of-range newborn screen result". Baby's First Test. Retrieved 2012-02-07.

- ^ Nanci Wilson (23 December 2009). "Newborn DNA samples to be destroyed". Austin News. Archived from the original on 24 December 2009. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d Goldenberg AJ, Sharp RR (February 2012). "The ethical hazards and programmatic challenges of genomic newborn screening". JAMA. 307 (5): 461–462. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.68. PMC 3868436. PMID 22298675.

- ^ a b c Clayton EW (2003). Newborn Genetic Screening. Contemporary Issues in Bioethics: Thomas Wadsworth. pp. 248–251. ISBN 978-0-495-00673-2.

- ^ Tarini BA, Christakis DA, Welch HG (August 2006). "State newborn screening in the tandem mass spectrometry era: more tests, more false-positive results". Pediatrics. 118 (2): 448–456. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-2026. PMID 16882794. S2CID 28070141.

Newborn screening

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and Early Implementation

Newborn screening originated with efforts to detect phenylketonuria (PKU), a genetic metabolic disorder causing intellectual disability if untreated due to the accumulation of phenylalanine from impaired metabolism. PKU was first identified in 1934 by Norwegian biochemist Asbjørn Følling, who linked elevated phenylalanine levels in urine to mental retardation in affected children. Dietary management restricting phenylalanine intake was demonstrated to prevent neurological damage in the 1950s, establishing the rationale for early detection before symptoms appear, as newborns are asymptomatic at birth.[12] In 1960, American microbiologist Robert Guthrie developed the first viable mass screening test for PKU, known as the Guthrie bacterial inhibition assay, which detects elevated phenylketonuria levels using dried blood spots collected via heel prick from infants. This method required only a small sample volume, enabling simple, cost-effective population-wide testing without specialized equipment beyond basic lab incubation. Guthrie's innovation was spurred by his niece's PKU diagnosis and the urgent need for scalable screening to implement timely dietary interventions, averting irreversible brain damage. The test's efficacy was validated through early trials, including those supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) in the early 1960s.[13][14][15][16] Early implementation began in 1963 when Massachusetts enacted the first U.S. state law mandating PKU screening for all newborns, marking the advent of systematic public health newborn screening programs. By 1965, 32 states had passed similar legislation, with most requiring universal testing shortly after birth, typically between 24 and 48 hours. This swift adoption reflected accumulating evidence from pilot programs showing that early identification allowed for effective treatment, dramatically reducing incidence of severe cognitive impairment in PKU cases. Initial challenges included logistical hurdles in sample collection and processing, as well as debates over mandatory versus voluntary screening, but empirical success in preventing disabilities drove widespread acceptance.[17][4][18]Expansion and Standardization in the United States

The expansion of newborn screening in the United States beyond phenylketonuria (PKU) began in the late 1960s and accelerated through the 1970s, incorporating conditions such as congenital hypothyroidism (mandated in many states by 1978) and galactosemia.[5] By the mid-1970s, PKU screening had achieved near-universal coverage, with 43 states enacting mandates and testing approximately 90% of newborns, culminating in all 50 states requiring it by 1985.[17][19] Sickle cell disease screening followed in the 1980s, with the first state mandates appearing around 1983, driven by evidence of early intervention benefits in affected populations.[5] Technological advancements, particularly the adoption of tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) in the 1990s, enabled multiplexed analysis of dried blood spots for multiple amino acid, organic acid, and fatty acid oxidation disorders simultaneously, expanding panels from fewer than 10 conditions to over 20 in adopting states.[5] Texas became the first state to mandate MS/MS-based screening in 1998, and by the early 2000s, most programs had integrated it, allowing detection of up to 40 or more disorders; for instance, New York expanded to 31 conditions using MS/MS in 2004.[20][21] This shift addressed prior limitations of single-analyte tests, increasing efficiency while maintaining specificity, though it raised concerns about false positives requiring follow-up diagnostics.[22] Standardization efforts gained momentum in the 2000s amid variability, with states screening for as few as 4 or as many as 50 conditions by 2005.[16] The American College of Medical Genetics issued a 2005 report recommending a core uniform panel of 29 conditions based on analytic validity, clinical utility, and public health impact, influencing state adoptions.[22] The Newborn Screening Saves Lives Act, signed into law on April 24, 2008, authorized federal grants for infrastructure, laboratory quality assurance, and education, while formalizing the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children (ACHDNC) to evaluate and recommend additions to the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP).[23][5] The RUSP, initially endorsed by ACHDNC in 2005 with 29 core conditions, was officially adopted by the Department of Health and Human Services in 2010 and has since expanded to 35 core and 26 secondary conditions as of 2021, incorporating disorders like severe combined immunodeficiency (added 2010) and spinal muscular atrophy (added 2018) following pilot data on treatability.[24][25] By April 2011, all states screened for at least 26 core RUSP conditions, and as of 2023, every state tests for a minimum of 31, though implementation remains state-determined without federal mandates.[16] This framework promotes harmonization through evidence-based criteria, yet disparities persist due to state funding and policy choices, with ongoing reauthorizations of the Act in 2014, 2019, and proposed for 2025 to sustain federal oversight.[26][27]International Developments and Harmonization Efforts

The International Society for Neonatal Screening (ISNS), established in the late 1980s, has facilitated global collaboration by disseminating guidelines for neonatal bloodspot screening programs and hosting international conferences to share best practices across more than 70 countries.[28][29] In 2025, ISNS renewed its general guidelines, emphasizing standardized processes for program organization, laboratory quality assurance, and follow-up care to support equitable implementation worldwide.[29] These efforts address variability in screening coverage, where high-income regions like North America and Europe screen for 20–60 conditions per program, while sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Latin America often limit to 1–5 core conditions due to infrastructural constraints.[30] The World Health Organization (WHO) has advanced international standardization through endorsements of priority screenings, recommending in 2023 universal bloodspot tests for 5–6 conditions including congenital hypothyroidism and hemoglobinopathies, linked to Sustainable Development Goal 3.2 for reducing neonatal mortality.[30] In April 2024, WHO issued implementation guidance for universal newborn screening targeting hearing loss, eye abnormalities, and hyperbilirubinemia, prioritizing integration into existing health systems with non-invasive tools, particularly in South-East Asia where coverage gaps persist.[31] These guidelines underscore evidence from cohort studies showing early detection reduces morbidity, though effectiveness hinges on treatment access, which remains uneven in low-resource settings.[31] Harmonization initiatives grapple with national disparities, as programs vary by condition panels, turnaround times, and false-positive rates; for instance, European nations screen heterogeneously for metabolic disorders despite shared public health goals.[30] In Europe, efforts since 2012 have focused on aligning processes from specimen collection to result interpretation, with EURORDIS advocating patient-driven criteria for adding conditions based on treatability and long-term outcomes rather than solely prevalence.[32][33] Global advocates, including the Association of Public Health Laboratories (APHL), support expansion in low- and middle-income countries via capacity-building partnerships, as outlined in 2023 strategies to adapt U.S.-style uniformity to local contexts without overextending unfeasible panels.[34] Challenges persist, including workforce shortages and cost barriers to genomic expansions, prompting calls for federated data platforms to benchmark outcomes and validate tests across borders.[35]Scientific Principles and Rationale

Core Criteria for Screening Conditions

The core criteria for selecting conditions suitable for newborn screening programs stem from the foundational principles established by J.M.G. Wilson and G. Jungner in their 1968 World Health Organization bulletin, which evaluate the viability of mass screening efforts based on disease characteristics, diagnostic feasibility, and intervention efficacy.[36] These 10 criteria prioritize conditions where early detection yields tangible health benefits without disproportionate harms or costs:- The condition must represent a significant public health problem, assessed by prevalence, severity, and potential for disability or mortality if untreated.[37]

- An effective treatment must exist for identified cases, altering disease progression or outcomes.[37]

- Diagnostic and treatment infrastructure must be accessible and operational at scale.[37]

- A detectable latent or presymptomatic phase must exist, allowing intervention before clinical manifestations.[37]

- A reliable screening test must be available, with high sensitivity, specificity, and acceptability to the screened population.[37]

- The test must be technically and economically viable for widespread application.[37]

- The natural history of the condition, including progression timelines, must be well-understood to inform screening intervals and thresholds.[37]

- Clear protocols must define treatment eligibility and management for screen-positive cases.[37]

- The total costs of screening, including follow-up diagnostics and false positives, must balance against overall healthcare expenditures and averted disease burdens.[37]

- Screening must operate as an ongoing public health process rather than a one-time initiative, with continuous evaluation and adjustment.[37]

Evidence-Based Justification for Newborn Screening

Newborn screening is justified by empirical evidence demonstrating that early detection of specific treatable disorders prevents severe morbidity, mortality, and developmental impairments that occur in unscreened populations. Implementation data from programs screening millions of infants annually show substantial improvements in outcomes for conditions like metabolic and endocrine disorders, where presymptomatic intervention alters disease trajectories. For instance, screening identifies approximately 3,400 U.S. infants yearly who benefit from timely treatment, reducing overall program-associated mortality and long-term healthcare costs.[1] In phenylketonuria (PKU), historical comparisons reveal that before universal screening began in the 1960s using the Guthrie bacterial inhibition assay, nearly all affected infants progressed to irreversible intellectual disability due to phenylalanine accumulation; post-screening dietary restrictions initiated within days of birth have largely eliminated such outcomes, with affected individuals achieving normal cognitive development when compliant.[41][42] Congenital hypothyroidism provides analogous evidence: newborn thyroid-stimulating hormone measurement enables levothyroxine therapy to avert cretinism and IQ deficits, with international programs confirming near-complete prevention of intellectual disability in screened cohorts compared to pre-screening eras dominated by late diagnosis.[43][42] For cystic fibrosis, controlled studies link screening-detected cases to enhanced nutritional status, accelerated lung function gains up to age 10, and postponed chronic pseudomonas infections versus symptom-based diagnosis, underscoring benefits from early enzyme replacement and monitoring.[44][45] Hemoglobinopathies such as sickle cell disease yield mortality reductions through screening-enabled penicillin prophylaxis and parental education, dropping U.S. under-3 mortality from over 10% pre-screening to under 1%, though systematic reviews note reliance on observational data rather than randomized trials.[46][47] Collectively, quality-assured programs with low false-positive follow-up losses affirm newborn screening's public health efficacy, supported by reduced disability incidence in screened versus historical unscreened groups.[42][1]Cost-Benefit Analysis from First Principles

Newborn screening programs derive their justification from the principle that early detection of treatable conditions yielding high-morbidity or mortality outcomes must generate net health and economic gains exceeding the incurred costs, accounting for disease prevalence, diagnostic accuracy, and intervention efficacy. The direct costs encompass specimen collection, laboratory analysis via methods like tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS), and confirmatory testing, typically ranging from $6 to $10 per infant for basic assays but escalating to 200 inclusive of program fees across U.S. states.[48][49][50] False-positive results, occurring in approximately 0.5-1% of screens, impose additional burdens through parental anxiety, repeat testing, and rare iatrogenic harms from unwarranted interventions.[51] Benefits accrue primarily through averted lifelong disabilities or deaths for conditions meeting Wilson-Jungner criteria, such as phenylketonuria (PKU), where untreated infants face profound intellectual impairment but dietary management initiated within weeks preserves normal cognition. For PKU screening in populations of 100,000 newborns, approximately 73 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) are gained versus no screening, with analogous gains for congenital hypothyroidism (CH).[52] Programs incorporating MS/MS for expanded metabolic disorders demonstrate benefit-cost ratios of 1:2.38 to 1:4.58 for PKU and related screens, reflecting savings from reduced institutionalization and special education needs.[53] Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) screening exemplifies high yield, yielding life-years saved at costs of 14 per infant screened, often with net economic benefits due to transplant success rates exceeding 90% when pre-symptomatic.[48][54] From causal fundamentals, net utility hinges on the differential between early treatment trajectories—yielding near-normal lifespans—and untreated paths dominated by irreversible organ damage or early mortality, discounted by low prevalence (e.g., 1:10,000-50,000 for core conditions). Aggregate U.S. evaluations of conventional panels estimate $310 per QALY saved, well below common thresholds like $50,000/QALY for cost-effectiveness.[55] However, expansions to ultra-rare disorders risk diminishing returns, as detection yields few cases amid amplified false positives, potentially eroding overall efficiency without commensurate evidence of treatment reversibility.[56] Empirical models underscore that reductions in medical expenditures are most pronounced for non-lethal but disabling disorders, where screening averts chronic care costs exceeding $1 million per case lifetime.[57]| Condition | Approximate Prevalence | QALYs Gained per 100,000 Screened | Incremental Cost per Infant |

|---|---|---|---|

| PKU | 1:10,000-15,000 | 73 | $3-10 (MS/MS add-on) |

| SCID | 1:58,000 | Variable; life-years saved | $4-8 |

| CH | 1:2,000-4,000 | Additive to PKU | Included in core panel |

Targeted Disorders

Metabolic Disorders

Newborn screening for metabolic disorders targets inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs), genetic conditions that disrupt biochemical pathways for processing amino acids, organic acids, fatty acids, or other metabolites, often leading to accumulation of toxic substances or energy shortages that can cause acute crises, developmental delays, or sudden death if untreated.[60] These disorders are detected primarily through tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) analysis of dried blood spots collected shortly after birth, allowing multiplex screening for multiple analytes simultaneously.[61] The expansion of MS/MS in the early 2000s enabled detection of dozens of IEMs beyond initial targets like phenylketonuria (PKU), significantly broadening panels while maintaining high specificity.[62] In the United States, the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP) designates core metabolic conditions for universal screening, with all states implementing tests for key amino acidopathies, organic acidemias, urea cycle defects, and fatty acid oxidation disorders (FAODs).[24] Phenylketonuria exemplifies successful screening outcomes; caused by mutations in the PAH gene impairing phenylalanine metabolism, it affects 1 in 10,000 to 15,000 newborns in the US.[63] Untreated PKU results in hyperphenylalaninemia and severe intellectual disability, but early detection via the Guthrie bacterial inhibition assay—pioneered in the 1960s and mandated starting in Massachusetts in 1963—followed by lifelong low-phenylalanine diet, has virtually eliminated profound neurological damage in screened populations.[64][65] Long-term studies confirm that early intervention yields normal cognitive development in most cases, though challenges persist with dietary adherence into adulthood.[66] Other amino acidopathies, such as maple syrup urine disease (MSUD), involve branched-chain amino acid metabolism defects with incidence around 1:185,000 births, treatable via protein-restricted diets and emergency decompensation protocols.[67] Organic acidemias like methylmalonic acidemia (MMA) and propionic acidemia present with metabolic acidosis and hyperammonemia; screening identifies cases at 1:50,000 to 100,000 incidence, enabling prompt interventions like carnitine supplementation and dialysis, which improve survival rates from historical near-zero to over 70% in screened cohorts.[68] Urea cycle disorders, such as argininosuccinic aciduria, disrupt nitrogen clearance leading to hyperammonemia; early diagnosis facilitates ammonia scavengers and dialysis, reducing neonatal mortality from 50-75% to under 25%.[69] Fatty acid oxidation disorders, including medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) deficiency—the most common FAOD at 1:15,000 to 20,000 births—predispose to hypoketotic hypoglycemia and sudden death during fasting; NBS-guided avoidance of prolonged fasting and carnitine therapy has eliminated most fatal episodes in identified infants.[68] Overall, expanded metabolic screening has demonstrated reduced morbidity and mortality across IEMs, with cohort studies showing screened individuals achieving better neurodevelopmental and survival outcomes compared to historical unscreened cases, though false positives necessitate confirmatory testing to minimize parental anxiety.[70][66] Challenges include variant interpretations and equitable access, but evidence supports net benefits from early detection.[69]Endocrinopathies and Hemoglobinopathies

Congenital hypothyroidism (CH) is the most common newborn-screened endocrinopathy, with an incidence of approximately 1 in 2,000 to 4,000 live births in the United States.[71][72] Screening involves measuring thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels from dried blood spots collected 24-48 hours after birth using immunoassay methods.[73][74] Elevated TSH prompts confirmatory serum testing of TSH and free thyroxine (T4) levels, with treatment initiated using oral levothyroxine if confirmed.[75] Untreated CH leads to severe intellectual disability, growth retardation, and motor abnormalities due to deficient thyroid hormone production affecting brain development.[75][76] Early screening and treatment normalize neurodevelopmental outcomes, preventing these deficits in nearly all cases.[77][78] Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), primarily due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency, affects about 1 in 15,000 newborns and is included in the uniform screening panel.[73] Detection relies on elevated 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP) levels measured via immunoassay on dried blood spots, with false positives reduced by second-tier steroid profiling or genetic testing in some programs.[79][80] The salt-wasting form, comprising roughly 75% of classic cases, causes life-threatening adrenal crisis from cortisol and aldosterone deficiency, with mortality exceeding 10% if undiagnosed.[81] Prompt glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid replacement after confirmation averts crises and supports normal growth, though long-term management addresses enzyme deficiency effects.[82] Screening identifies cases before symptoms, reducing neonatal mortality, though challenges persist with preterm infants showing transient elevations.[83] Hemoglobinopathies screened include sickle cell disease (SCD) variants such as hemoglobin SS, SC, and S-β-thalassemia, with an overall U.S. incidence of about 4.9 per 10,000 births, higher in African American populations at 1 in 365 for SCD.[84][85] Analysis uses high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) or isoelectric focusing on dried blood spots to identify abnormal hemoglobin fractions like Hb S and absent/normal Hb A.[86] Positive results trigger confirmatory testing and referral to hematology for penicillin prophylaxis starting at 2 months, which reduces invasive pneumococcal infection mortality by over 80%.[87] Newborn screening has lowered under-5 mortality from SCD by enabling early interventions like hydroxyurea and transfusions, shifting median survival beyond 40 years in screened cohorts.[85][88] Carrier detection (e.g., AS trait) informs family counseling but does not alter immediate newborn care.[89] Other hemoglobinopathies, such as β-thalassemia major, may be detected if programs include extended profiling, though primary focus remains on clinically significant SCD forms due to their acute risks like vaso-occlusive crises and splenic sequestration.[86] Universal screening ensures equitable identification regardless of ancestry, with CDC-supported data tracking improving long-term surveillance.[90]Infectious and Structural Conditions

Critical congenital heart disease (CCHD) screening, implemented via pulse oximetry, detects structural heart defects present at birth that impair systemic blood flow or oxygenation, affecting approximately 2 to 3 per 1,000 live births in the United States.[91] The test measures pre- and post-ductal oxygen saturation levels typically between 24 and 48 hours after birth; a result below 95% in either extremity or a difference greater than 3% between sites prompts referral for echocardiography, with sensitivity ranging from 76% to 91% and specificity over 99%.[91] Added to the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP) in September 2011, CCHD screening became mandatory in all U.S. states by 2016, reducing undetected cases and enabling timely interventions like prostaglandin infusion or surgery, which improve survival rates from under 70% historically to over 90% with early detection.[24][92] Congenital hearing loss, screened universally using physiological methods such as otoacoustic emissions (OAE) or auditory brainstem response (ABR), identifies structural or sensorineural impairments in approximately 1 to 3 per 1,000 newborns, with structural causes including inner ear malformations or auditory canal atresia.[93] Recommended by the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing since 1990 and incorporated into the RUSP, this point-of-care screening occurs before hospital discharge or within the first month, achieving referral rates of 2-4% and enabling early amplification or cochlear implantation to mitigate language delays.[93][24] All U.S. states mandate it through Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) programs, with follow-up diagnostic audiometry confirming permanent bilateral or unilateral loss.[93] Direct newborn screening for infectious conditions remains limited in the U.S., with no congenital infections listed as core RUSP disorders, though indirect detection occurs via hearing screening for sequelae of pathogens like cytomegalovirus (CMV).[24] Congenital CMV, the most common congenital infection affecting 0.5-0.7% of U.S. births, causes hearing loss in 10-15% of cases overall and up to 50% of symptomatic infants, prompting targeted testing (e.g., urine or saliva PCR within 21 days) for those failing initial hearing screens in most states.[94][95] Universal cCMV screening, using non-invasive swabs, is mandated only in Minnesota since 2023, identifying cases for antiviral therapy like valganciclovir, which preserves hearing in 80% of treated infants per clinical trials.[96][97] Other congenital infections, such as syphilis or HIV, rely on maternal prenatal testing and risk-based newborn evaluation rather than routine universal screening, with syphilis cases rising to 3,755 reported in 2022 despite CDC guidelines for maternal retesting at 28 weeks and delivery.[98][99]Emerging Genomic and Rare Conditions