Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

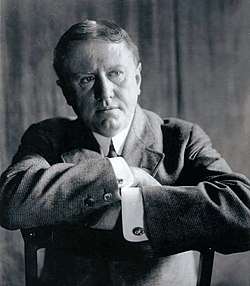

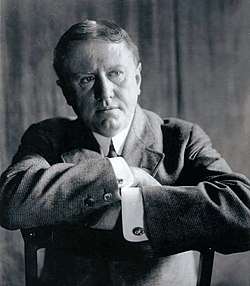

O. Henry

View on Wikipedia

William Sydney Porter (September 11, 1862 – June 5, 1910), better known by his pen name O. Henry, was an American writer known primarily for his short stories, though he also wrote poetry and non-fiction. His works include "The Gift of the Magi", "The Duplicity of Hargraves", and "The Ransom of Red Chief", as well as the novel Cabbages and Kings. Porter's stories are known for their naturalist observations, witty narration, and surprise endings.

Key Information

Born in Greensboro, North Carolina, Porter worked at his uncle's pharmacy after finishing school and became a licensed pharmacist at age 19. In March 1882, he moved to Texas, where he initially lived on a ranch, and later settled in Austin, where he met his first wife, Athol Estes. While working as a drafter for the Texas General Land Office, Porter began developing characters for his short stories. He later worked for the First National Bank of Austin, while also publishing a weekly periodical, The Rolling Stone.

In 1895, he was charged with embezzlement stemming from an audit of the bank. Before the trial, he fled to Honduras, where he began writing Cabbages and Kings (in which he coined the term "banana republic"). Porter surrendered to U.S. authorities when he learned his wife was dying from tuberculosis, and he cared for her until her death in July 1897. He began his five-year prison sentence in March 1898 at the Ohio Penitentiary, where he served as a night druggist. While imprisoned, Porter published 14 stories under various pseudonyms, one being O. Henry.

Released from prison early for good behavior, Porter moved to Pittsburgh to be with his daughter Margaret before relocating to New York City, where he wrote 381 short stories. He married Sarah (Sallie) Lindsey Coleman in 1907; she left him two years later. Porter died on June 5, 1910, after years of deteriorating health. Porter's legacy includes the O. Henry Award, an annual prize awarded to outstanding short stories.

Biography

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

Early life

[edit]William Sidney Porter was born on September 11, 1862, in Greensboro, North Carolina, during the American Civil War. He changed the spelling of his middle name to Sydney in 1898. His parents were Algernon Sidney Porter (1825–88), a physician, and Mary Jane Virginia Swaim Porter (1833–65). William's parents had married on April 20, 1858. When William was three, his mother died after giving birth to her third child, and he and his father moved into the home of his paternal grandmother. As a child, Porter was always reading, everything from classics to dime novels; his favorite works were Lane's translation of One Thousand and One Nights and Burton's The Anatomy of Melancholy.[2]

Porter graduated from his aunt Evelina Maria Porter's elementary school in 1876. He then enrolled at the Lindsey Street High School. His aunt continued to tutor him until he was 15. In 1879, he started working in his uncle's drugstore in Greensboro, and on August 30, 1881, at the age of 19, Porter was licensed as a pharmacist. At the drugstore, he also showed his natural artistic talents by sketching the townsfolk.

Life in Texas

[edit]

Porter traveled along with James K. Hall to Texas in March 1882, hoping that a change of air would help alleviate a persistent cough he had developed. He took up residence on the sheep ranch of Richard Hall, James Hall's son, in La Salle County and helped out as a shepherd, ranch hand, cook, and baby-sitter. While on the ranch, he learned bits of Spanish and German from the mix of indigenous and immigrant ranch hands. He also spent time reading classic works of literature.

Porter's health did improve. He traveled with Richard to Austin, Texas, in 1884, where he decided to remain and was welcomed into the home of Richard's friends, Joseph Harrell, and his wife. Porter resided with the Harrells for three years. He went to work briefly for the Morley Brothers Drug Company as a pharmacist. Porter then moved on to work for the Harrell Cigar Store located in the Driskill Hotel. He also began writing as a sideline and wrote many of his early stories in the Harrell house.

As a young bachelor, Porter led an active social life in Austin. He was known for his wit, story-telling, and musical talents. He played both the guitar and mandolin. He sang in the choir at St. David's Episcopal Church and became a member of the "Hill City Quartette", a group of young men who sang at gatherings and serenaded young women of the town.

Porter met and began courting Athol Estes, 17 years old and from a wealthy family. Historians believe Porter met Athol at the laying of the cornerstone of the Texas State Capitol on March 2, 1885. Her mother objected to the match because Athol was ill, suffering from tuberculosis. On July 1, 1887, Porter eloped with Athol and they were married in the parlor of the home of the Reverend R. K. Smoot, pastor of the Central Presbyterian Church, where the Estes family attended church. The couple continued to participate in musical and theater groups, and Athol encouraged her husband to pursue his writing. Athol gave birth to a son in 1888, who died hours after birth, and then a daughter Margaret Worth Porter in September 1889.

Porter's friend Richard Hall became Texas Land Commissioner and offered Porter a job. Porter started as a draftsman at the Texas General Land Office (GLO) on January 12, 1887, at a salary of $100 a month, drawing maps from surveys and field notes. The salary was enough to support his family, but he continued his contributions to magazines and newspapers. In the GLO building, he began developing characters and plots for such stories as "Georgia's Ruling" (1900), and "Buried Treasure" (1908). The castle-like building he worked in was woven into some of his tales such as "Bexar Scrip No. 2692" (1894). His job at the GLO was a political appointment by Hall. Hall ran for governor in the election of 1890 but lost. Porter resigned on January 21, 1891, the day after the new governor, Jim Hogg, was sworn in.

The same year, Porter began working at the First National Bank of Austin as a teller and bookkeeper at the same salary he had made at the GLO. The bank was operated informally, and Porter was apparently careless in keeping his books and may have embezzled funds. In 1894, he was accused by the bank of embezzlement and lost his job but was not indicted at the time.

He then worked full-time on his humorous weekly called The Rolling Stone, which he started while working at the bank. The Rolling Stone featured satire on life, people, and politics and included Porter's short stories and sketches. Although eventually reaching a top circulation of 1,500, The Rolling Stone failed in April 1895 because the paper never provided an adequate income. However, his writing and drawings had caught the attention of the editor at the Houston Post.

Porter and his family moved to Houston in 1895, where he started writing for the Post. His salary was only $25 a month, but it rose steadily as his popularity increased. Porter gathered ideas for his column by loitering in hotel lobbies and observing and talking to people there. This was a technique he used throughout his writing career.

While he was in Houston, federal auditors audited the First National Bank of Austin and found the embezzlement shortages that led to his firing. A federal indictment followed, and he was arrested on charges of embezzlement.

Flight and return

[edit]

After his arrest, Porter's father-in-law posted his bail. He was due to stand trial on July 7, 1896, but the day before, as he was changing trains to get to the courthouse, he got scared. He fled, first to New Orleans and later to Honduras, with which the United States had no extradition treaty at that time. Porter lived in Honduras for six months, until January 1897. There he became friends with Al Jennings, a notorious train robber, who later wrote a book about their friendship.[3] He holed up in a Trujillo hotel, where he wrote Cabbages and Kings, which notably coined the term "banana republic".[4] Porter had sent Athol and Margaret back to Austin to live with Athol's parents. Unfortunately, Athol became too ill to meet Porter in Honduras as he had planned. When he learned that his wife was dying, Porter returned to Austin in February 1897 and surrendered to the court, pending trial. Athol Estes Porter died from tuberculosis (then known as consumption) on July 25, 1897.

Porter had little to say in his own defense at his trial and was found guilty on February 17, 1898, of embezzling $854.08. He was sentenced to five years in prison and imprisoned on March 25, 1898, at the Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus, Ohio. Porter was a licensed pharmacist and was able to work in the prison hospital as the night druggist. He was given his own room in the hospital wing, and there is no record that he actually spent time in the cell block of the prison. He had 14 stories published under various pseudonyms while he was in prison but was becoming best known as "O. Henry", a pseudonym that first appeared over the story "Whistling Dick's Christmas Stocking" in the December 1899 issue of McClure's Magazine. A friend of his in New Orleans would forward his stories to publishers so that they had no idea that the writer was imprisoned.

Porter was released on July 24, 1901, for good behavior after serving three years. He reunited with his daughter Margaret, now age 11, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where Athol's parents had moved after Porter's conviction.

Later life

[edit]Porter's most prolific writing period started in 1902, when he moved to New York City to be near his publishers. While there, he wrote 381 short stories. He wrote a story a week for over a year for the New York World Sunday Magazine. His wit, characterization, and plot twists were adored by his readers but often panned by critics.

Porter married again in 1907 to childhood sweetheart Sarah (Sallie) Lindsey Coleman, whom he met again after revisiting his native state of North Carolina. Coleman was herself a writer and wrote a romanticized and fictionalized version of their correspondence and courtship in her novella Wind of Destiny.[5]

Death

[edit]Porter was a heavy drinker, and by 1908, his markedly deteriorating health affected his writing. In 1909, Sarah left him, and he died on June 5, 1910, of cirrhosis of the liver, complications of diabetes, and an enlarged heart. According to one account, he died of cerebral hemorrhage.[6]

After funeral services in New York City, he was buried in the Riverside Cemetery in Asheville, North Carolina.[7] His daughter Margaret Worth Porter had a short writing career from 1913 to 1916. She married cartoonist Oscar Cesare of New York in 1916; they were divorced four years later. She died of tuberculosis in 1927 and was buried next to her father.

According to the cemetery, as of 2023, people have been leaving $1.87 in change (the amount of Della's savings at the beginning of "The Gift of the Magi") on Porter's grave for at least 30 years. The cemetery says the money is given to area libraries.[8]

Stories

[edit]

Most of Porter's stories are set in his own time, the early 20th century. He had an obvious affection for New York City, which he called "Bagdad-on-the-Subway",[9] and many of his stories are set there, while others are set in small towns or in other cities. They frequently feature working class characters, such as policemen and waitresses, as well as criminals and social outcasts. In his day he was called the American answer to French naturalist Guy de Maupassant, whose work was similarly concerned with the struggles of common people and often had twist endings.

Cabbages and Kings was his first collection of stories, followed by The Four Million. The second collection opens with a reference to Ward McAllister's claim that there were "...only 'Four Hundred' people in New York City who were really worth noticing. But a wiser man has arisen—the census taker—and his larger estimate of human interest has been preferred in marking out the field of these little stories of the Four Million."

His final work was "Dream", a short story intended for the magazine The Cosmopolitan. It was never completed.[10]

Among his most famous stories are:

- "The Gift of the Magi" is about a young couple, Jim and Della, who are short of money but desperately want to buy each other Christmas gifts. Unbeknownst to Jim, Della sells her most valuable possession, her beautiful hair, in order to buy a platinum fob chain for Jim's watch; while unbeknownst to Della, Jim sells his own most valuable possession, his watch, to buy jeweled combs for Della's hair. The essential premise of this story has been copied, re-worked, parodied, and otherwise re-told countless times in the century since it was written.

- "The Ransom of Red Chief" in which two men kidnap a boy of ten years old to ransom him. The boy turns out to be so spoiled and obnoxious that the desperate men ultimately pay the boy's father $250 to take him back.

- "The Cop and the Anthem" about a New York City hobo named Soapy who sets out to get arrested so that he can be a guest of the city jail instead of sleeping out in the cold winter. Despite his best efforts at committing petty theft, vandalism, disorderly conduct, and "flirting" with a young prostitute, Soapy fails to draw the attention of the police. Dejected, he stops in front of a church, where an organ anthem inspires him to clean up his life; however, he is charged with loitering, and sentenced to three months in prison.

- "A Retrieved Reformation" tells the tale of safecracker Jimmy Valentine, a man recently freed from prison. He goes to a town bank to case it before he robs it. As he walks to the door, he catches the eye of the banker's beautiful daughter. They immediately fall in love and Valentine decides to give up his criminal career. He moves into the town, taking up the identity of Ralph Spencer, a shoemaker. Just as he is about to leave to deliver his specialized tools to an old associate, a lawman who recognizes him arrives at the bank. Jimmy and his fiancée and her family are at the bank, inspecting a new safe when a child accidentally gets locked inside the airtight vault. Knowing it will seal his fate, Valentine opens the safe to rescue the child. However, much to Valentine's surprise, the lawman denies recognizing him and lets him go.

- "The Duplicity of Hargraves" tells the story of the Talbots, a father and daughter from the Old South, newly poor after the Civil War, who move to Washington, DC. An actor, Hargraves, offers Mr. Talbot money, which he is too proud to accept. But when Talbot is approached by an old man, a former slave who gives him money to settle an old family debt, he accepts it. It is later revealed that Hargraves secretly portrayed the slave.

- "The Caballero's Way" in which Porter's most famous character, the Cisco Kid, is introduced. It was first published in 1907 in the July issue of Everybody's Magazine and collected in the book Heart of the West that same year. In later film and TV depictions, the Kid would be portrayed as a dashing adventurer, perhaps skirting the edges of the law, but primarily on the side of the angels. In the original short story, the only story by Porter to feature the character, the Kid is a murderous, ruthless border desperado, whose trail is dogged by a heroic Texas Ranger.

Pen name

[edit]Porter used a number of pen names (including "O. Henry" or "Olivier Henry") in the early part of his writing career; other names included S.H. Peters, James L. Bliss, T.B. Dowd, and Howard Clark.[11] Nevertheless, the name "O. Henry" seemed to garner the most attention from editors and the public, and was used exclusively by Porter for his writing by about 1902. He gave various explanations for the origin of his pen name.[12] In 1909, he gave an interview to The New York Times, in which he gave an account of it:

It was during these New Orleans days that I adopted my pen name of O. Henry. I said to a friend: "I'm going to send out some stuff. I don't know if it amounts to much, so I want to get a literary alias. Help me pick out a good one." He suggested that we get a newspaper and pick a name from the first list of notables that we found in it. In the society columns we found the account of a fashionable ball. "Here we have our notables," said he. We looked down the list and my eye lighted on the name Henry, "That'll do for a last name," said I. "Now for a first name. I want something short. None of your three-syllable names for me." "Why don't you use a plain initial letter, then?" asked my friend. "Good," said I, "O is about the easiest letter written, and O it is."

A newspaper once wrote and asked me what the O stands for. I replied, "O stands for Olivier, the French for Oliver." And several of my stories accordingly appeared in that paper under the name Olivier Henry.[13]

William Trevor writes in the introduction to The World of O. Henry: Roads of Destiny and Other Stories (Hodder & Stoughton, 1973) that "there was a prison guard named Orrin Henry" in the Ohio State Penitentiary "whom William Sydney Porter ... immortalised as O. Henry".

According to J. F. Clarke, it is from the name of the French pharmacist Etienne Ossian Henry, whose name is in the U.S. Dispensary which Porter used working in the prison pharmacy.[14]

Writer and scholar Guy Davenport offers his own hypothesis: "The pseudonym that he began to write under in prison is constructed from the first two letters of Ohio and the second and last two of penitentiary."[12]

Legacy

[edit]The O. Henry Award is an annual prize named after Porter and given to outstanding short stories.

A film was made in 1952 featuring five stories, called O. Henry's Full House. The episode garnering the most critical acclaim[15] was "The Cop and the Anthem" starring Charles Laughton and Marilyn Monroe. The other stories are "The Clarion Call", "The Last Leaf", "The Ransom of Red Chief", and "The Gift of the Magi".

Strictly Business is a 1962 Soviet comedy film, directed by Leonid Gaidai, based on three short stories by O. Henry: "The Roads We Take", "Makes the Whole World Kin", and "The Ransom of Red Chief". The premiere of the film was timed to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the birth of the writer. Henry was particularly popular in Russia in the 1920s, and was described by the critic Deming Brown in 1953 as "remain[ing] a minor classic in Russia".[16] In 1962, the Soviet Postal Service issued a stamp commemorating O. Henry's 100th birthday.

A 1957 television series, The O. Henry Playhouse, was syndicated in 39 episodes to 188 markets.[17] Actor Thomas Mitchell portrayed O. Henry in each episode as he interacted with his characters or related his latest story to his publisher or a friend.[18]

The 1986 Indian anthology television series Katha Sagar adapted several of Henry's short stories as episodes including "The Last Leaf".

An opera in one long act, The Furnished Room, with music by Daniel Steven Crafts and libretto by Richard Kuss, is based on O. Henry's story of the same name.

The O. Henry House and O. Henry Hall, both in Austin, Texas, are named for him. O. Henry Hall, now owned by the Texas State University System, previously served as the federal courthouse in which O. Henry was convicted of embezzlement. The O. Henry House has been the site of the O. Henry Pun-Off, an annual spoken word competition inspired by Porter's love of language, since 1978. (Dr. Samuel E. Gideon, a historical architect and professor at the University of Texas at Austin, was a strong advocate for the saving of the O. Henry House in Austin.)

Several schools are named for Porter: William Sydney Porter Elementary in Greensboro, North Carolina,[19] O. Henry Elementary in Garland, Texas, the O. Henry School (I.S. 70) in New York City,[20] and O. Henry Middle School in Austin, Texas.[21]

The O. Henry Hotel in Greensboro is also named for Porter, as is US 29, which is O. Henry Boulevard.

Asheville, North Carolina, where Porter is buried, has O. Henry Avenue, the location of the Asheville Citizen-Times building.[22]

On September 11, 2012, the United States Postal Service issued a stamp commemorating the 150th anniversary of O. Henry's birth.[23]

On November 23, 2011, Barack Obama quoted O. Henry while granting pardons to two turkeys named "Liberty" and "Peace".[24] In response, political science professor P. S. Ruckman Jr. and Texas attorney Scott Henson filed a formal application for a posthumous pardon in September 2012, the same month that the U.S. Postal Service issued its O. Henry stamp.[25] Previous attempts were made to obtain such a pardon for Porter in the administrations of Woodrow Wilson, Dwight Eisenhower, and Ronald Reagan,[26] but no one had ever bothered to file a formal application.[27] Ruckman and Henson argued that Porter deserved a pardon because (1) he was a law-abiding citizen prior to his conviction; (2) his offense was minor; (3) he had an exemplary prison record; (4) his post-prison life clearly indicated rehabilitation; (5) he would have been an excellent candidate for clemency in his time, had he but applied for pardon; (6) by today's standards, he remains an excellent candidate for clemency; and (7) his pardon would be a well-deserved symbolic gesture and more.[25] The pardon remains ungranted.

In 2021 the Library of America included O. Henry in their list by publishing a collection of 101 of his stories, edited by Ben Yagoda.[28]

Bibliography

[edit]Stories

[edit]Collections:

- Cabbages and Kings (1904), novel consisting of linked stories. Collection of 19 short stories:

- "The Proem: By the Carpenter", "'Fox-in-the-Morning'", "The Lotus and the Bottle", "Smith", "Caught", "Cupid's Exile Number Two", "The Phonograph and the Graft", "Money Maze", "The Admiral", "The Flag Paramount", "The Shamrock and the Palm", "The Remnants of the Code", "Shoes", "Ships", "Masters of Arts", "Dicky", "Rouge et Noir", "Two Recalls", "The Vitagraphoscope"

- The Four Million (1906), collection of 25 short stories:

- "Tobin's Palm", "The Gift of the Magi", "A Cosmopolite in a Cafe", "Between Rounds", "The Skylight Room", "A Service of Love", "The Coming-Out of Maggie", "Man About Town", "The Cop and the Anthem", "An Adjustment of Nature", "Memoirs of a Yellow Dog", "The Love-Philtre of Ikey Schoenstein", "Mammon and the Archer", "Springtime à la Carte", "The Green Door", "From the Cabby's Seat", "An Unfinished Story", "The Caliph, Cupid and the Clock", "Sisters of the Golden Circle", "The Romance of a Busy Broker", "After Twenty Years", "Lost on Dress Parade", "By Courier", "The Furnished Room", "The Brief Debut of Tildy"

- The Trimmed Lamp (1907), collection of 25 short stories:

- "The Trimmed Lamp", "A Madison Square Arabian Night", "The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball", "The Pendulum", "Two Thanksgiving Day Gentlemen", "The Assessor of Success", "The Buyer from Cactus City", "The Badge of Policeman O'Roon", "Brickdust Row" (made into the 1918 film, Everybody's Girl), "The Making of a New Yorker", "Vanity and Some Sables", "The Social Triangle", "The Purple Dress", "The Foreign Policy of Company 99", "The Lost Blend", "A Harlem Tragedy", "'The Guilty Party'", "A Midsummer Knight's Dream", "According to Their Lights", "The Last Leaf", "The Count and the Wedding Guest", "The Country of Elusion", "The Ferry of Unfulfilment", "The Tale of a Tainted Tenner", "Elsie in New York"

- Heart of the West (1907), collection of 19 short stories:

- "Hearts and Crosses", "The Ransom of Mack", "Telemachus, Friend", "The Handbook of Hymen", "The Pimienta Pancakes", "Seats of the Haughty", "Hygeia at the Solito", "An Afternoon Miracle", "The Higher Abdication", "Cupid à la Carte", "The Caballero's Way", "The Sphinx Apple", "The Missing Chord", "A Call Loan", "The Princess and the Puma", "The Indian Summer of Dry Valley Johnson", "Christmas by Injunction", "A Chaparral Prince", "The Reformation of Calliope"

- The Gentle Grafter (1908), collection of 14 short stories:

- "The Octopus Marooned", "Jeff Peters as a Personal Magnet", "Modern Rural Sports", "The Chair of Philanthromathematics", "The Hand That Riles the World", "The Exact Science of Matrimony", "A Midsummer Masquerade", "Shearing the Wolf", "Innocents of Broadway", "Conscience in Art", "The Man Higher Up", "A Tempered Wind", "Hostages to Momus", "The Ethics of Pig"

- The Voice of the City (1908), collection of 25 short stories:

- "The Voice of the City", "The Complete Life of John Hopkins", "A Lickpenny Lover", "Dougherty's Eye-opener", "'Little Speck in Garnered Fruit'", "The Harbinger", "While the Auto Waits", "A Comedy in Rubber", "One Thousand Dollars", "The Defeat of the City", "The Shocks of Doom", "The Plutonian Fire", "Nemesis and the Candy Man", "Squaring the Circle", "Roses, Ruses and Romance", "The City of Dreadful Night", "The Easter of the Soul", "The Fool-killer", "Transients in Arcadia", "The Rathskeller and the Rose", "The Clarion Call", "Extradited from Bohemia", "A Philistine in Bohemia", "From Each According to His Ability", "The Memento"

- Roads of Destiny (1909), collection of 22 short stories:

- "Roads of Destiny", "The Guardian of the Accolade", "The Discounters of Money", "The Enchanted Profile", "Next to Reading Matter", "Art and the Bronco", "Phoebe", "A Double-dyed Deceiver", "The Passing of Black Eagle", "A Retrieved Reformation", "Cherchez la Femme", "Friends in San Rosario", "The Fourth in Salvador", "The Emancipation of Billy", "The Enchanted Kiss", "A Departmental Case", "The Renaissance at Charleroi", "On Behalf of the Management", "Whistling Dick's Christmas Stocking", "The Halberdier of the Little Rheinschloss", "Two Renegades", "The Lonesome Road"

- Options (1909), collection of 16 short stories:

- "'The Rose of Dixie'", "The Third Ingredient", "The Hiding of Black Bill", "Schools and Schools", "Thimble, Thimble", "Supply and Demand", "Buried Treasure", "To Him Who Waits", "He Also Serves", "The Moment of Victory", "The Head-hunter", "No Story", "The Higher Pragmatism", "Best-seller", "Rus in Urbe", "A Poor Rule"

- The Two Women (1910), collection of 2 short stories:

- "A Fog in Santone", "Blind Man's Holiday"

- Strictly Business (1910), collection of 23 short stories:

- "Strictly Business", "The Gold That Glittered", "Babes in the Jungle", "The Day Resurgent", "The Fifth Wheel", "The Poet and the Peasant", "The Robe of Peace", "The Girl and the Graft", "The Call of the Tame", "The Unknown Quantity", "The Thing's the Play", "A Ramble in Aphasia", "A Municipal Report", "Psyche and the Pskyscraper", "A Bird of Bagdad", "Compliments of the Season", "A Night in New Arabia", "The Girl and the Habit", "Proof of the Pudding", "Past One at Rooney's", "The Venturers", "The Duel", "'What You Want'"

- Whirligigs (1910), collection of 24 short stories:

- "The World and the Door", "The Theory and the Hound", "The Hypotheses of Failure", "Calloway's Code", "A Matter of Mean Elevation", "Girl", "Sociology in Serge and Straw", "The Ransom of Red Chief", "The Marry Month of May", "A Technical Error", "Suite Homes and Their Romance", "The Whirligig of Life", "A Sacrifice Hit", "The Roads We Take", "A Blackjack Bargainer", "The Song and the Sergeant", "One Dollar's Worth", "A Newspaper Story", "Tommy's Burglar", "A Chaparral Christmas Gift", "A Little Local Colour", "Georgia's Ruling", "Blind Man's Holiday", "Madame Bo-Peep of the Ranches"

- Sixes and Sevens (1911), collection of 25 short stories:

- "The Last of the Troubadours", "The Sleuths", "Witches' Loaves", "The Pride of the Cities", "Holding Up a Train", "Ulysses and the Dogman", "The Champion of the Weather", "Makes the Whole World Kin", "At Arms with Morpheus", "A Ghost of a Chance", "Jimmy Hayes and Muriel", "The Door of Unrest", "The Duplicity of Hargraves", "Let Me Feel Your Pulse", "October and June", "The Church with an Overshot-Wheel", "New York by Camp Fire Light", "The Adventures of Shamrock Jolnes", "The Lady Higher Up", "The Greater Coney", "Law and Order", "Transformation of Martin Burney", "The Caliph and the Cad", "The Diamond of Kali", "The Day We Celebrate"

- Rolling Stones (1912), collection of

- 23 short stories: "The Dream", "A Ruler of Men", "The Atavism of John Tom Little Bear", "Helping the Other Fellow", "The Marionettes", "The Marquis and Miss Sally", "A Fog in Santone", "The Friendly Call", "A Dinner at ———", "Sound and Fury" (1903), "Tictocq", "Tracked to Doom", "A Snapshot at the President", "An Unfinished Christmas Story", "The Unprofitable Servant", "Aristocracy Versus Hash", "The Prisoner of Zembla", "A Strange Story", "Fickle Fortune, or How Gladys Hustled", "An Apology", "Lord Oakhurst's Curse", "Bexar Scrip No. 2692.", "Queries and Answers"

- 12 poems:

- "The Pewee", "Nothing to say", "The Murderer"

- Some Postscripts: "Two Portraits", "A Contribution", "The Old Farm", "Vanity", "The Lullaby Boy", "Chanson de Bohême", "Hard to Forget", "Drop a Tear in This Slot", "Tamales"

- letters: "Some Letters"

- Waifs and Strays (1917), collection of 12 short stories:

- "The Red Roses of Tonia", "Round The Circle", "The Rubber Plant's Story", "Out of Nazareth", "Confessions of a Humorist", "The Sparrows in Madison Square", "Hearts and Hands", "The Cactus", "The Detective Detector", "The Dog and the Playlet", "A Little Talk About Mobs", "The Snow Man"

- O. Henryana (1920), collection of 7 short stories:

- "The Crucible", "A Lunar Episode", "Three Paragraphs", "Bulger's Friend", "A Professional Secret", "The Elusive Tenderloin", "The Struggle of the Outliers"

- Postscripts (1923), collection of 103 short stories, 26 poems and 4 articles:

- "The Sensitive Colonel Jay", "Taking No Chances", "A Matter of Loyalty", "The Other Side of It", "Journalistically Impossible", "The Power of Reputation", "The Distraction of Grief", "A Sporting Interest", "Had A Use for It", "The Old Landmark", "A Personal Insult", "Toddlekins" (poem), "Reconciliation", "Buying a Piano", "Too Late", "Nothing to say" (poem), "'Goin Home fur Christmas'" (poem), "Just a Little Damp", "Her Mysterious Charm", "Convinced", "His Dilemma", "Something for Baby" (poem), "Some Day", "A Green Hand", "A Righteous Outburst", "Getting at the Facts", "Just for a Change" (poem), "Too Wise", "A Fatal Error", "Prompt" (poem), "An Opportunity Declined", "Correcting a Great Injustice", "A Startling Demonstration", "Leap Year Advice" (article), "After Supper", "His Only Opportunity", "Getting Acquainted", "Answers to Inquiries" (article), "City Peril", "Hush Money", "Relieved", "No Time to Lose", "A Villainous Trick", "A Forced March" (poem), "Book Review" (article), "A Conditional Pardon", "Inconsistency" (poem), "Bill Nye", "To a Portrait" (poem), "A Guarded Secret", "A Pastel", "Jim" (poem), "Board and Ancestors", "An X-Ray Fable", "A Universal Favorite", "Spring" (poem), "The Sporting Editor on Culture", "A Question of Direction", "The Old Farm" (poem), "Willing to Compromise", "Ridiculous", "Guessed Everything Else", "The Prisoner of Zembla", "Lucky Either Way", "The Bad Man", "Slight Mistake", "Delayed", "A Good Story Spoiled", "Revenge", "No Help for It", "Riley's Luck" (poem), "Not So Much a Tam Fool", "A Guess-Proof Mystery Story", "Futility" (poem), "Wounded Veteran", "Her Ruse", "Why Conductors Are Morose", "The Pewee" (poem), "'Only to Lie-'" (poem), "The Sunday Excursionist", "Decoration Day", "Charge of the White Brigade" (poem), "An Inspiration", "Coming To Him", "His Pension", "Winner", "Hungry Henry's Ruse", "A Proof Of Love" (poem), "One Consolation", "An Unsuccessful Experiment", "Superlatrives" (poem), "By Easy Stages", "Even Worse", "The Shock", "The Cynic", "Speaking of Big Winds", "An Original Idea", "Calculations", "A Valedictory", "Solemn Thoughts", "Explaining It", "Her Failing", "A Disagreement", "An E for a Knee" (poem), "The Unconquerable" (poem), "An Expensive Veracity", "Grounds for Uneasiness", "It Covers Errors" (poem), "Recognition", "His Doubt", "A Cheering Thought", "What It Was", "Vanity" (poem), "Identified", "The Apple", "How It Started", "How Red Conlin Told the Widow", "Why He Hesitated", "Turkish Questions" (poem), "Somebody Lied", "Marvelous", "The Confession of a Murderer", "Get Off the Earth" (poem), "The Stranger's Appeal", "The Good Boy", "The Colonel's Romance", "A Narrow Escape", "A Year's Supply", "Eugene Field" (poem), "Slightly Mixed", "Knew What Was Needed", "Some Ancient News Notes" (article), "A Sure Method"

- O. Henry Encore (1939), collection of 27 short stories, 7 sketches and 10 poems:

- Part one. Stories: "A Night Errant", "In Mezzotint", "The Dissipated Jeweller", "How Willie Saved Father", "The Mirage on the Frio", "Sufficient Provocation", "The Bruised Reed", "Paderewski's Hair", "A Mystery of Many Centuries", "A Strange Case", "Simmons' Saturday Night", "An Unknown Romance", "Jack the Giant Killer", "The Pint Flask", "An Odd Character", "A Houston Romance", "The Legend of San Jacinto", "Binkley's Practical School of Journalism", "A New Microbe", "Vereton Villa", "Whisky Did It", "Nothing New Under the Sun", "Led Astray", "A Story for Men", "How She Got in the Swim", "The Barber Talks", "Barber Shop Adventure"

- Part two. Sketches: "Did You See the Circus", "Thanksgiving Remarks", "When the Train Comes in", "Christmas Eve", "New Year's Eve and Now it Came to Houston", "'Watchman, What of the Night?'", "Newspaper Poets"

- Part three. Newspaper Poetry: "Topical Verse", "Cap Jessamines", "The Cricket", "My Broncho", "The Modern Venus", "Celestial Sounds", "The Snow", "Her Choice", "'Little Things, but Ain't They Whizzers?'", "Last Fall of the Alamo"

Uncollected short stories:

- "Tictocq, the Great French Detective" (1894)

- "Tictocq, the Great French Detective; or, A Soubrette's Diamonds" (1894)

- "A Blow All 'Round" (1895)

- "A Chicago Proposal" (1895)

- "A Fishy Story" (1895)

- "A Foretaste" (1895)

- "A Literal Caution" (1895)

- "A Philadelphia Diagnosis" (1895)

- "A Thousand Dollar Poem, was what the Literary Judgment of the Business Manager Lost for the Paper" (1895)

- "All Right" (1895)

- "And Put Up a Dime" (1895)

- "Arrived" (1895)

- "As Her Share" (1895)

- "Ballad of the Passionate Eye" (1895)

- "Cheaper in Quantities" (1895)

- "Didn't Want Him Back" (1895)

- "Do You Know?" (1895)

- "Enlarging His Field" (1895)

- "Entirely Successful" (1895)

- "Extremes Met" (1895)

- "False to His Colors" (1895)

- "Family Pride" (1895)

- "He Was Behind With His Board" (1895)

- "Her Reckoning" (1895)

- "His Last Chance" (1895)

- "Making the Most of It" (1895)

- "Might Be" (1895)

- "Military or Millinery?" (1895)

- "No Chestnuts Were Served" (1895)

- "No Earlier" (1895)

- "Not Hers" (1895)

- "Not Official Statistics, However" (1895)

- "Palmistry" (1895)

- "Prodigality" (1895)

- "Professional, But Doubtful" (1895)

- "Prudent Precautions" (1895)

- "Same Thing" (1895)

- "Self Conceit" (1895)

- "Silver Question Settled" (1895)

- "Sunday Journalism, Memoranda of the Sabbath Editor of the New York Daily for Next Sunday's Contents" (1895)

- "The Fate It Deserved" (1895)

- "The Man at the Window" (1895)

- "The Modern Kind" (1895)

- "The New Hero" (1895)

- "The Odor Located" (1895)

- "The Teacher Taught" (1895)

- "The White Feather" (1895)

- "Uncle Sam's Wind" (1895)

- "Whole Handfuls" (1895)

- "Will She Fight as She Jokes? Here Are Some Translations of Recent Spanish Humour" (1895)

- "Yellow Specials, Latest Style of News Write Ups adopted by the sulphur-hued journals" (1895)

- "A Tragedy" (1896, as The Postman)

- "At an Auction" (1896)

- "Telegram" (1896)

- "His Courier" (1902)

- "The Flag" (1902)

- "The Guardian of the Scutcheon" (1903, as Olivier Henry)

- "The Lotus and the Cockleburrs" (1903)

- "The Point of the Story" (1903, as Sydney Porter)

- "The Quest of Soapy" (1908)

- "A Christmas Pi" (1909, as O. H-nry)

- "Adventures in Neurasthenia" (1910)

- "Last Story" (1910)

Poems

[edit]Uncollected poems:

- "Already Provided" (1895)

- "Archery" (1895)

- "At Cockcrow" (1895)

- "Honeymoon Vapourings" (1895)

- "Never, Until Now" (1895)

- "Ornamental" (1895)

- "The Imported Brand" (1895)

- "The Morning glory" (1895)

- "The White Violet" (1895)

- "To Her" (XRay) Photograph" (1895)

- "Unseeing" (1895)

- "Promptings" (1899)

- "Sunset in the Far North" (1901)

- "The Captive" (1901)

- "Uncaptured Joy" (1901)

- "April" (1903)

- "Auto Bugle Song" (1903)

- "June" (1903)

- "Remorse" (1903)

- "Spring in the City" (1903)

- "To a Gibson Girl" (1903)

- "Two Chapters" (1903)

- "A Floral Valentine" (1905)

Non-fiction

[edit]- Later Definitions (1895)

- The Reporter's Private Lexicon (1903)

- Letter 1883 (1912)

- Letters 1884, 1885 (1912)

- Letters 1905 (1914)

- Letters from Prison to his Daughter Margaret (1916)

- Letter 1901 (1917)

- Letters (1921)

- Letters to Lithopolis: from O. Henry to Mabel Wagnalls (1922)

- Letters (1923)

- Letter (1928)

- Letters 1906, 1909 (1931)

- Letters, etc. of 1883 (1931)

References

[edit]- ^ "The Marquis and Miss Sally", Everybody's Magazine, vol 8, issue 6, June 1903, appeared under the byline "Oliver Henry"

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). . Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company.

- ^ "Biography: O. Henry". North Carolina History. Archived from the original on March 10, 2014. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

- ^ Chapman, Peter (2008). Bananas: How the United Fruit Company Shaped the World. Cannongate, New York. pp. 68–69, 108.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Current-Garcia, Eugene (1993). O. Henry: A Study of the Short Fiction (First ed.). New York City: Twayne Publishers, Macmillan Publishing Co. p. 123. ISBN 0-8057-0859-6.

- ^ Brown CT (October 1967). "O. Henry the pharmacist". Mil Med. 132 (10): 823–825. doi:10.1093/milmed/132.10.823. PMID 4965475.

- ^ Darty, Joshua (2018). Asheville's Riverside Cemetery. Arcadia. ISBN 9781467128193.

- ^ Boyle, John (November 30, 2023). "Answer Man: What happens to coins on O. Henry's gravesite in Riverside Cemetery? Any hope for dangerous Riverside Drive interchange?". Asheville Watchdog. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ Henry, O. "A Madison Square Arabian Night," from The Trimmed Lamp: "Oh, I know what to do when I see victuals coming toward me in little old Bagdad-on-the-Subway. I strike the asphalt three times with my forehead and get ready to spiel yarns for my supper. I claim descent from the late Tommy Tucker, who was forced to hand out vocal harmony for his pre-digested wheaterina and spoopju." The Trimmed Lamp Archived September 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Project Gutenberg text

- ^ Henry, O. "Dream". Read Book Online website. Archived from the original on October 19, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ "Porter, William Sydney (O. Henry)". Ncpedia.org.

- ^ a b Guy Davenport, The Hunter Gracchus and Other Papers on Literature and Art, Washington, D.C.: Counterpoint, 1996.

- ^ "'O. Henry' on Himself, Life, and Other Things" (PDF), New York Times, April 4, 1909, p. SM9.

- ^ Joseph F. Clarke (1977). Pseudonyms. BCA. p. 83.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (October 17, 1952). "The Screen in Review; Four O. Henry Short Stories Offered in Fox Movie at Trans-Lux 52d Street Archived November 17, 2017, at the Wayback Machine". New York Times. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ^ Brown, Deming (October 1953). "O. Henry in Russia". The Russian Review. 12 (4): 253–258. doi:10.2307/125957. JSTOR 125957. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ The Billboard, May 13, 1957.

- ^ "Celebrating The O. Henry Playhouse". ohenryplayhouse.com. Archived from the original on December 19, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

- ^ Arnett, Ethel Stephens (1973). For Whom Our Public Schools Were Named, Greensboro, North Carolina. Piedmont Press. p. 245.

- ^ "The toughest job in education". New York Times. April 13, 1986.

- ^ "O. Henry Middle School, Austin, TX". Archive.austinisd.org. Archived from the original on October 4, 2011. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ Burgess, Joel (October 31, 2023). "Halloween in haunted Asheville?: DIY tour of the city's ghost sites". Asheville Citizen-Times.

- ^ "Celebrating Master Storyteller O. Henry's 150th Birthday Anniversary". U.S. Postal Service. About.usps.com. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ Mark Memmot, "Obama Quotes O. Henry on 'Purely American' Nature of Thanksgiving", The Two-Way, NPR.org. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ^ a b Jim Schlosser, "Please Mr. President, Pardon O. Henry Archived September 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine", O. Henry Magazine, October 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ^ "Presidential Pardons: Few from Obama, and None for O. Henry". Go.bloomberg.com. February 21, 2013. Archived from the original on June 26, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ Edith Evan Asbury, "For O. Henry, a Hometown Festival", The New York Times, April 13, 1985. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ^ "O. Henry: 101 Stories Edited by Ben Yagoda". Library of America. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Smith, C. Alphonso (November 1916). "The Strange Case of Sydney Porter and 'O. Henry'". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XXXIII (1): 54–64. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

External links

[edit]- Works by O. Henry in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by O. Henry at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about O. Henry at the Internet Archive

- Works by O. Henry at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- O. Henry Museum

- Biography and Works at LiteratureCollection.com (archived)

- "His Writers' Workshop? A Prison Cell", John J. Miller, The Wall Street Journal, June 8, 2010

- O. Henry at IMDb

- Portal to Texas History, The University of North Texas Libraries

- O. Henry Collection

- Partial Bibliography in "O. Henry (William Sydney Porter) Resource Guide".

- Catalogue

- O. Henry at Library of Congress, with 235 library catalog records

O. Henry

View on GrokipediaBiography

Early Life

William Sydney Porter, later known by his pen name O. Henry, was born on September 11, 1862, in Greensboro, North Carolina, to Dr. Algernon Sidney Porter, a physician of English and Dutch ancestry, and Mary Jane Virginia Swaim Porter.[1][2] The family belonged to the middle class, with some affluence connected to Porter's great-uncle, Jonathan Worth, who served as governor of North Carolina from 1865 to 1868.[1][5] Porter was the middle child of three sons; his father was known as an inventor and occasional drinker, while the household provided a stable though modest environment.[6] Porter's early childhood was marked by tragedy when his mother died of tuberculosis in 1865, at age three.[6][7] Following her death, he and his brother were raised primarily by their paternal grandmother, a self-trained doctor, and their aunt, Evelina (Lina) Porter, in Aunt Lina's home.[2][6] Under his aunt's influence, Porter received private tutoring and developed a deep love for stories, poetry, and language, fostering his lifelong passion for literature.[8] His formal education was brief, limited to attendance at a local school and his aunt's private instruction until age fifteen.[1][5] At that point, Porter left school to apprentice as a clerk and pharmacist in his uncle Clark Porter's drugstore in Greensboro, where he honed skills in compounding prescriptions and eventually earned his pharmacist's license in 1881.[2][5] During this period, he pursued personal interests in drawing—sketching local townspeople—and writing, alongside avid reading that shaped his creative inclinations.[2][6] In 1882, facing his own respiratory health issues possibly linked to tuberculosis exposure, Porter accepted a position as a draftsman for the Texas-Mexican Railway, marking his initial step into broader professional opportunities beyond Greensboro.[2][5]Texas Period

In 1882, at the age of 19, William Sydney Porter relocated to Texas seeking relief from a persistent cough exacerbated by his smoking habit and the damp climate of North Carolina; he initially worked as a ranch hand on a sheep ranch in La Salle County owned by cattleman Richard Hall, son of his uncle's friend Dr. James Hall. By 1884, Porter had moved to Austin, where he lived as a boarder with the family of county clerk Joseph Harrell and took up a series of jobs to support himself, including pharmacist at Morley's Drug Store—leveraging his prior licensing from his uncle's pharmacy in Greensboro—bookkeeper, clerk at a hardware store, and draftsman at the Texas General Land Office from 1887 to 1891, where he sketched maps and handled surveying records. In 1891, he joined the First National Bank of Austin as a teller and bookkeeper, earning a salary of $100 per month, a position that provided stability but also exposed him to the financial pressures of the growing city.[2][9][3] On July 5, 1887, Porter eloped with 17-year-old Athol Estes, the daughter of a prosperous Austin merchant, marrying in a small ceremony at Flower Hill despite initial family opposition due to Porter's modest background and uncertain prospects; the couple settled into a rented cottage on East Fifth Street, where Athol's artistic interests and encouragement fostered Porter's creative side. Their first child, a son, was born in 1888 but died in infancy, a tragedy compounded by Athol's diagnosis with tuberculosis shortly after; in 1889, daughter Margaret Worth Porter was born on September 30, bringing joy amid ongoing hardships, as the family navigated financial strains from Porter's irregular income and Athol's medical needs, often relying on her parents' occasional support. Porter doted on Margaret, incorporating fatherly themes into his later works, while the couple's life reflected the era's challenges for young families in a booming but unequal frontier city.[2][9][3] Porter's early creative pursuits in Austin blossomed through his involvement in the local arts scene; he played mandolin in the Teco Club orchestra, a group of young professionals who performed at social events, and sang baritone with the Hill City Quartette at weddings, festivals, and picnics, honing his ear for dialogue and humor drawn from everyday Texan life. His writing began as sketches and cartoons, including illustrations for J. W. Wilbarger's Indian Depredations in Texas in 1889, and evolved into contributions for local outlets under pseudonyms like Olivier Henry, a variation he later explained as the French form of Oliver. In 1894, seeking an outlet for his satirical bent, Porter purchased a failing press and revived a short-lived weekly called the Iconoclast before renaming it The Rolling Stone, a humor publication featuring his witty columns, poems, and stories that lampooned Austin society and reached a circulation of about 1,000 in a city of 11,000 residents, though it folded after a year due to poor sales.[2][9][10] By the mid-1890s, Porter's growing interest in short fiction was evident in his Rolling Stone pieces and freelance submissions to the Houston Post, where he wrote a regular column from 1895 to 1896 under the byline "O. Henry," an early iteration of his famous pen name possibly derived from a mishearing of "Oh, Henry" during a catcall or a reference to the Ohio State Penitentiary (though the latter connection emerged later). These efforts showcased his knack for ironic observations of Southwestern characters—cowboys, tramps, and clerks—foreshadowing the twist endings of his mature style, with initial stories gaining notice in national magazines like McClure's by 1899, just as suspicions arose over financial discrepancies at the bank where shortfalls in accounts led to embezzlement allegations against him.[2][9][3]Legal Troubles and Imprisonment

In 1895, an audit of the First National Bank of Austin revealed accounting discrepancies totaling between $1,000 and $1,800 during William Sydney Porter's tenure as a teller and bookkeeper, prompting federal investigation.[11] Although the exact cause—whether intentional embezzlement or sloppy record-keeping—remains debated among historians, Porter was indicted on February 10, 1896, for embezzling approximately $854 from the bank.[12] To evade the impending trial, Porter fled Austin in July 1896, traveling first to New Orleans before boarding a steamer to Honduras, a Central American "banana republic" with no extradition treaty with the United States; this episode later inspired his novel Cabbages and Kings.[13] Porter's time in Honduras was brief and arduous, marked by poverty and isolation, but he returned to Texas by late 1896 or early 1897 upon receiving word of his wife Athol's worsening tuberculosis.[12] Athol, who had been diagnosed with the terminal illness, died on July 25, 1897, leaving Porter to care for their young daughter Margaret, who was placed under the guardianship of family members during the ensuing legal proceedings.[11] With little defense presented at his trial in early 1898—amid personal grief and financial desperation—Porter was convicted on March 25, 1898, of embezzlement and sentenced to five years in a federal penitentiary.[13] Porter entered the Ohio State Penitentiary in Columbus on April 21, 1898, where he was assigned as a night druggist in the prison hospital, a role that afforded him daytime hours for reading and writing.[14] During his incarceration, he composed approximately 15 short stories, sketches, and humorous pieces, submitting them anonymously to magazines like McClure's and Ainslee's for publication; these early works, written under various pseudonyms, marked the beginning of his serious literary output and helped support his family.[12] For good behavior, Porter served only three years and was released on July 24, 1901.[13]New York Years

Upon his release on parole from the Ohio State Penitentiary on July 24, 1901, after serving three years and three months of a five-year sentence for embezzlement, William Sydney Porter, writing under the pseudonym O. Henry, sought to distance himself from the scandal surrounding his conviction in Texas. He briefly reunited with his young daughter Margaret in Pittsburgh before relocating to New York City in the spring of 1902, where he aimed to reinvent himself amid the anonymity of the bustling metropolis and draw inspiration from its diverse populace.[12][15] Over the next eight years, Porter resided in a series of modest apartments across Manhattan, including locations in Greenwich Village, Chelsea, and Harlem, such as 55 Irving Place near Gramercy Park and 28 West 26th Street.[16] In New York, Porter's productivity soared as he adopted a nomadic routine, often composing his stories late into the night in saloons, parks, and boarding house dining rooms like the Caledonia on West 26th Street or Pete's Tavern on Irving Place, where he observed the city's eclectic characters for material. From 1903 to 1906, he supplied the New York World Sunday Magazine with one short story per week, contributing to a total output of over 300 stories during his lifetime, the majority penned in this period under the O. Henry name.[16][17] His earnings fluctuated wildly; initial advances and sales at rates up to 25 cents per word brought brief financial comfort, but reckless spending on drink and failed ventures, including a collaborative theatrical production with Franklin P. Adams that never reached Broadway, led to mounting debts and reliance on editorial loans.[16][18] On November 27, 1907, Porter married his childhood sweetheart, Sara "Sallie" Lindsey Coleman, in Asheville, North Carolina, partly in an effort to curb his alcoholism and stabilize his life; the couple briefly relocated to Long Island before returning to the city. However, the union strained under Porter's persistent drinking and Coleman's own health problems, culminating in an amicable separation by 1909, after which she returned south.[19] His health, already compromised by years of heavy alcohol consumption, deteriorated rapidly from cirrhosis of the liver and diabetes, prompting repeated but unsuccessful attempts at sobriety and a trip to Texas in 1909 for recovery amid his declining output and isolation.[1][19]Death

In the final months of his life, William Sydney Porter, known by his pen name O. Henry, suffered from worsening health complications stemming from chronic alcoholism, diabetes, and cirrhosis of the liver.[20] On June 3, 1910, he collapsed suddenly in New York City and was rushed to the New York Polyclinic Hospital on East Thirty-fourth Street, where he received treatment for these conditions without undergoing surgery.[21] These ailments represented the culmination of health struggles that had persisted from his earlier years of heavy drinking and personal hardships.[2] Porter died two days later, on June 5, 1910, at the age of 47, succumbing to cirrhosis of the liver, diabetes, and an enlarged heart.[20] His second wife, Sara Lindsey Coleman Porter, was in Asheville, North Carolina, at the time and arrived too late to be at his bedside.[21] Funeral services were held on June 7, 1910, at the Episcopal Church of the Transfiguration in New York City, often called the "Little Church Around the Corner," officiated by Rev. Dr. George C. Houghton.[21] His body was then transported to Asheville, North Carolina, for burial in Riverside Cemetery, where he was interred beside the grave of his first wife, Athol Estes Porter.[20] At the time of his death, Porter left behind significant financial difficulties, including substantial debts that burdened his estate and complicated arrangements for his daughter, Margaret Worth Porter, who was 20 years old.[18] Margaret, Porter's only surviving child from his first marriage, was placed under the care of family friends and later pursued a brief writing career before marrying cartoonist Oscar Cesare in 1916 and, after their divorce, Alec J. Sartin in 1927 shortly before her death.[2][22][19] Immediate tributes from literary circles highlighted Porter's renown under his pseudonym, with contemporary accounts describing him as "one of the best short story writers in America" known primarily as O. Henry, a name that had eclipsed his real identity in public recognition.[21]Literary Career

Adoption of the Pen Name

Following his release from the Ohio State Penitentiary in 1901, William Sydney Porter settled in New York City and continued his professional authorship under the pen name "O. Henry," with the pseudonym's first use appearing in the published story "Whistling Dick's Christmas Stocking" in McClure's Magazine in December 1899, during his imprisonment. During his imprisonment from 1898 to 1901, Porter had composed stories under various aliases, including "Oliver Henry," but shifted to "O. Henry" for his emerging literary identity. The adoption marked a deliberate evolution as he sought to establish a distinct persona amid his post-prison career start.[2][23] The exact origins of the "O. Henry" pseudonym remain shrouded in uncertainty, with several leading theories proposed by scholars and contemporaries. One prominent explanation links it to Orrin Henry, a guard at the Ohio State Penitentiary where Porter served his sentence, suggesting the name was adapted from this figure as a subtle nod to his incarceration environment.[24] Another theory attributes the pseudonym to Étienne-Ossian Henry, a 19th-century French pharmacist whose name appeared in the U.S. Dispensatory, a pharmaceutical reference book Porter consulted during his prison duties as a night druggist.[25] A third interpretation views it as a whimsical inversion of "Ohio Penitentiary," playfully encoding the site of his imprisonment through the initials "O.P." rearranged.[26] Alternative accounts, including those from Porter himself, describe the name's selection as more arbitrary. In a 1909 New York Times interview, Porter recounted choosing "Henry" at random from a society column in a New Orleans newspaper during his fugitive period there in 1896–1897, pairing it with "O." as a simple initial that he later claimed represented "Olivier," the French form of Oliver.[27] These varied explanations highlight Porter's tendency to offer evolving stories about the pseudonym, possibly to deflect curiosity about his past. The primary purpose of adopting "O. Henry" was to ensure anonymity, shielding Porter's young daughter and family from the ongoing scandal of his embezzlement conviction while granting him creative freedom to pen satirical observations on American society without direct personal association. This veil of separation proved essential as his stories gained popularity, allowing him to navigate literary circles unencumbered by his history.[2]Short Story Publications

O. Henry, the pen name of William Sydney Porter, produced a total of 381 short stories between 1899 and 1910, most of which first appeared in popular magazines such as Ainslee's Magazine and Cosmopolitan.[28] These publications provided a platform for his rapid output, allowing him to establish a reputation for witty, concise narratives drawn from everyday life. To meet the demands of his career in New York City, O. Henry adopted a rigorous publication strategy, often writing one story per week for outlets like the New York World Sunday Magazine, where he was paid approximately $100 per story.[28][29] Many of these pieces were initially serialized in periodicals before being gathered into book collections, enabling him to sustain a livelihood through consistent, high-volume production. Among his major short story collections, Cabbages and Kings (1904) stands out as a novel-length work composed of interlinked stories set in the fictional Latin American republic of Anchuria, exploring themes of political intrigue and expatriate life.[30] The Four Million (1906) followed, featuring 25 urban tales depicting the lives of ordinary New Yorkers, countering the era's focus on high society by celebrating the city's vast, uncelebrated population.[31] Subsequent volumes included The Trimmed Lamp (1907), a set of 25 stories often centered on working women navigating city hardships; Heart of the West (1907), which drew on Western motifs with 19 tales of frontier humor and romance; and Roads of Destiny (1909), comprising 22 varied narratives touching on fate and adventure across diverse settings.[32][33][34] Several individual stories from this period achieved lasting fame. "A Retrieved Reformation" (1903), first published in Cosmopolitan, recounts the redemption of safecracker Jimmy Valentine, who reforms after falling in love and opening a shoe store.[35] "The Cop and the Anthem" (1904) follows homeless man Soapy's ironic attempts to get arrested for winter shelter in New York, only to face an unexpected arrest just as he resolves to change his life. "The Gift of the Magi" (1905), originally in the New York Sunday World, portrays a young couple's sacrificial exchange of Christmas gifts—her hair for a watch fob chain, his watch for combs—highlighting mutual devotion.[36] "The Ransom of Red Chief" (1907), appearing in The Saturday Evening Post, depicts two hapless kidnappers whose plan backfires when their young captive turns the ordeal into a boisterous adventure, leading them to pay the boy's father to take him back. While many stories were collected during O. Henry's lifetime, numerous others remained unanthologized, scattered across magazines. Posthumous compilations have since gathered these, including Sixes and Sevens (1911), Rolling Stones (1912), and Waifs and Strays (1917).[37] A significant modern effort is the 2021 Library of America edition O. Henry: 101 Stories, edited by Ben Yagoda, which selects and annotates 101 tales, incorporating previously uncollected works to provide a comprehensive view of his output.[38]Other Writings

In addition to his renowned short stories, O. Henry ventured into longer prose forms with the novel Cabbages and Kings, published in 1904. This work consists of interconnected stories set in the fictional Central American republic of Anchuria, particularly the coastal town of Coralio, where American expatriates navigate political intrigue, revolutions, and eccentric adventures amid a backdrop of tropical instability.[39] The narrative draws inspiration from O. Henry's brief exile in Honduras in 1896, during which he evaded embezzlement charges by fleeing the United States, capturing the chaotic essence of "banana republic" life through satirical portrayals of corruption and whimsy.[40] Though structured as a novel, it retains O. Henry's signature episodic style, with the title borrowed from Lewis Carroll's poem "The Walrus and the Carpenter" to evoke the absurdity of worldly affairs.[39] O. Henry also produced a modest body of poetry, estimated at around two dozen pieces, often infused with humor, sentiment, or light satire and published sporadically in magazines during his career. These verses, typically brief and accessible, explore themes of everyday life, nature, and human folly, as seen in examples like "The Pewee," a whimsical reflection on a bird's song, and "Nothing to Say," a playful commentary on silence and expression.[41] Many remained uncollected during his lifetime but appeared posthumously in volumes such as Postscripts (1923), which gathered early journalistic writings alongside poems including "The Lullaby Boy" and "Chanson de Bohême," showcasing his lyrical side amid more narrative-focused output.[42] His non-fiction contributions, primarily from his early journalistic endeavors, encompass editorials, sketches, and essays that total numerous pieces, frequently published unsigned or under pseudonyms. In the 1890s, while in Texas, O. Henry founded and edited the weekly humor newspaper *The Rolling Stone* (1894–1895), where he authored most of the content, including satirical editorials lampooning local politicians, social customs, business practices, and state institutions, as well as fictionalized sketches like mock news accounts from imaginary publications.[10] These were later compiled in the 1913 collection Rolling Stones, which includes letters, queries-and-answers columns, historical articles such as "Bexar Scrip No. 2692," and personal anecdotes drawn from his time at the paper and contributions to the Houston Post.[43] Later, during his New York years, he penned brief essays on urban life for magazines, offering observational insights into the city's rhythms, though these were less voluminous than his prose fiction. His travel impressions from Honduras, while not issued as standalone pieces, informed the vivid settings in Cabbages and Kings.[43] O. Henry's forays into drama were limited and largely unfinished, with efforts like collaborative playwriting in his later years yielding no major productions during his lifetime.Writing Style and Themes

Twist Endings and Plot Structure

O. Henry's short stories are renowned for their twist endings, which typically involve unexpected reversals that occur in the final moments, often unveiling layers of irony, pathos, or comic revelation. These conclusions transform seemingly ordinary narratives into memorable vignettes, appearing in a significant portion of his approximately 300 published tales, though not all adhere strictly to this formula. The technique draws readers into a false sense of predictability before subverting expectations, a device that contributed substantially to his commercial success in early 20th-century magazines.[44][45] Structurally, O. Henry's plots employ deceptively straightforward progression, building tension through misdirection and subtle foreshadowing that conceals the impending reversal. This approach echoes influences from detective fiction and the surprise narratives of Guy de Maupassant, whom O. Henry admired for his ironic twists, though O. Henry infused his versions with American vernacular humor and urban immediacy. The stories often unfold in a linear fashion, focusing on commonplace characters and situations to lull the audience, only for the denouement to reframe the preceding events in a poignant or humorous light.[46][47] Representative examples illustrate this mastery. In "The Gift of the Magi" (1905), a young couple's mutual sacrifices—Della selling her hair for a watch chain and Jim pawning his watch for combs—render their gifts impractical, underscoring the irony of selfless love. Similarly, "The Ransom of Red Chief" (1907) inverts a kidnapping scheme when the victim's boisterous antics terrorize the criminals, leading them to pay the father $250 to reclaim the boy, turning presumed profit into loss through comedic reversal.[45][48] Over his career, O. Henry's use of twist endings evolved from the more whimsical and adventure-laden plots of his early Texas-period stories, which often featured lighthearted escapades and coincidences, to the darker, more socially pointed conclusions in his New York tales. Later works, such as those in The Trimmed Lamp (1907), incorporated sharper critiques of urban inequality and human folly, with reversals emphasizing pathos amid economic hardship rather than pure fancy.[49][45] Critics have lauded the ingenuity of these structures for their entertainment value and narrative economy, yet contemporaries like H. L. Mencken dismissed them as contrived, faulting O. Henry's reliance on mechanical tricks over character depth and labeling his style "smoke-room and variety show smartness," where figures serve as puppets in formulaic setups. Despite such rebukes, the twist endings remain a defining element, influencing generations of short fiction writers.[46][50]Humor, Irony, and Social Observation

O. Henry's humor often relied on colloquial dialogue, puns, and exaggerated characters to capture the vibrancy of urban and Western settings, drawing from the Southwestern humor tradition that emphasized vernacular speech and playful exaggeration.[29] In stories like "The Trimmed Lamp," he employed witty banter among working-class New Yorkers to highlight everyday absurdities, such as a shopgirl's ambitious dreams clashing with harsh realities, creating a lighthearted yet pointed tone.[51] This style peppered his narratives with wordplay and arcane terms, making the ordinary seem comically extraordinary while avoiding heavy moralizing.[29] His use of irony frequently took dramatic and cosmic forms, where characters' intentions backfire in unexpected ways, underscoring fate's capricious nature. In "The Cop and the Anthem," the protagonist Soapy deliberately seeks arrest to secure winter shelter, only to be apprehended ironically when he abandons his scheme and behaves respectably, illustrating cosmic irony through the universe's cruel misalignment of effort and outcome.[52] Dramatic irony appears when readers foresee the twist before characters, as in "A Harlem Tragedy," where sarcastic undertones mock domestic violence through a husband's repentant gift-giving that sparks neighborly envy.[51] These elements often intertwined with his signature surprise endings to amplify thematic depth without overt explanation.[53] O. Henry's social observations centered on the lives of New York's "four million" ordinary citizens, subtly critiquing class divides, rampant consumerism, and the struggles of immigrant communities amid urban industrialization. In collections like The Four Million, he contrasted the elite "Four Hundred" with working-class figures such as shopgirls and laborers, portraying consumerism's hollow promises through tales of fleeting luxuries that fail to bridge social gaps.[29] Immigrant experiences, depicted in stories like "The City of the Dreadful Night," highlighted tenement diversity and ethnic prejudices, such as Italian and Irish characters navigating prejudice and opportunity in saloons and streets, without descending into didacticism.[51] His narratives reflected Progressive Era tensions, challenging social norms by humanizing the masses against elite exclusivity.[54] Influenced by Mark Twain's vernacular style and Charles Dickens' vivid character sketches, O. Henry blended folksy dialogue with detailed portraits of societal undercurrents to enrich his commentary.[29] Twain's Southwestern humor shaped his exaggerated, pun-filled depictions of American life, while Dickens' focus on urban poverty informed his empathetic yet ironic views of class and city dwellers.[55] Many of O. Henry's stories featured strong female protagonists who navigated economic hardships with resilience, alongside subtle explorations of racial dynamics. Shopgirls like Nancy in "The Trimmed Lamp" embody ambition and wit, rejecting superficial romance for self-reliance amid class barriers.[51] In "The Duplicity of Hargraves," a Black comedian outwits a prejudiced Southern gentleman, offering a nuanced nod to post-Reconstruction racial tensions through role reversal and ironic justice.Legacy

Influence on Literature

O. Henry's innovative approach to the short story, particularly his mastery of surprise endings and concise plotting, significantly shaped the modern form, leading to the establishment of the O. Henry Prize in 1919 as an annual award for outstanding short fiction in his honor.[56] This prestigious recognition, administered by organizations like PEN America, has since highlighted exceptional work by emerging and established authors, perpetuating O. Henry's emphasis on narrative economy and unexpected twists as hallmarks of the genre.[56] His influence extended to later writers, including Roald Dahl, whose adult short stories drew on O. Henry's skillful plotting and ironic reversals, as seen in Dahl's collections of macabre tales with similar structural surprises.[57] Similarly, Irwin Shaw's early short fiction, frequently anthologized in O. Henry Prize collections, reflected the master's focus on urban vignettes and moral ambiguities, contributing to Shaw's rise as a prominent mid-20th-century storyteller.[58] In the realm of American literature, O. Henry bridged 19th-century romanticism and 20th-century modernism through his contributions to urban realism, portraying the lives of anonymous city dwellers in New York with vivid, unromanticized detail.[45] Stories like those in The Four Million depicted the everyday struggles of immigrants, laborers, and the working poor amid the metropolis's bustle, emphasizing social observation over heroic individualism and thus paving the way for later realist writers who explored modernity's alienation.[15] This focus on the "little people" of urban America humanized the anonymous masses, influencing the genre's shift toward psychological depth and social commentary in the interwar period.[45] O. Henry's work achieved substantial international reach, with his stories translated into dozens of languages and adapted globally to reflect local contexts. In the Soviet Union during the 1960s, several film adaptations repurposed his narratives as critiques of capitalism, such as the 1962 comedy "Strictly Business," which combined three O. Henry tales to satirize American greed and exploitation under a socialist lens.[59] These adaptations, including "Kings and Cabbage" (1965), highlighted themes of inequality in ways that aligned with Soviet ideology, broadening O. Henry's appeal beyond Western audiences.[59] Scholarly assessments of O. Henry's legacy reveal a trajectory of early acclaim followed by decline and partial revival. His immense popularity in the early 20th century, driven by accessible humor and sentimentality, waned by the 1930s as critics dismissed his work for excessive melodrama and formulaic twists, viewing it as outdated amid rising modernism.[60] However, postmodern literary analysis has revived interest in his irony and subversion of expectations, interpreting his endings as critiques of bourgeois illusions rather than mere tricks.[44] O. Henry's educational legacy endures through the widespread anthologization of his stories in school curricula around the world since the 1920s, fostering appreciation for concise narrative craft among young readers.[61] Classics like "The Gift of the Magi" remain staples in English language arts programs, teaching themes of sacrifice and irony while introducing students to American literary traditions.[62] This ongoing inclusion underscores his role in shaping global literacy efforts. The 2025 edition of the O. Henry Prize collection, featuring winners such as works by Chika Unigwe and Dave Eggers, further evidences his enduring impact on contemporary short fiction.[63]Awards, Adaptations, and Recent Recognition

The O. Henry Award, established in 1918 by the Society of Arts and Sciences in New York to commemorate the legacy of William Sydney Porter shortly after his death, recognizes exceptional short fiction and has been presented annually since 1919. Early selections were compiled by the Society, with collections later published by Doubleday beginning in the mid-20th century, and since 2009, the award has operated in partnership with PEN America, publishing the PEN/O. Henry Prize Stories anthology each year.[64][65][66] Several memorials preserve Porter's life and work. The O. Henry House in Austin, Texas—his residence from 1884 to 1894—was relocated and restored by the city in 1934, opening as a museum that displays period furnishings and manuscripts. In Greensboro, North Carolina, his birthplace, a trio of bronze sculptures depicting O. Henry, his dog, and an open book of stories was dedicated in 2014 as part of the city's public art collection. The annual O. Henry Pun-Off World Championships, launched in 1978 at the Austin museum, draw thousands for punning contests inspired by his humorous style and hold the Guinness World Record as the longest-running pun competition.[67][68][69] O. Henry's tales have inspired numerous adaptations across film, television, and theater. The 1952 anthology film O. Henry's Full House, produced by 20th Century Fox, dramatized five of his New York-era stories, including "The Cop and the Anthem" and "The Gift of the Magi," with segments directed by Henry Koster, Henry Hathaway, and others, narrated by John Steinbeck. In the 1980s, television productions included a 1980 adaptation of "The Gift of the Magi" as a short film and an episode of the CBS Library anthology series featuring "The Chaparral Prince" in 1982. Stage versions encompass Broadway-area musicals like the 1985 off-Broadway production Gifts of the Magi, which blended two O. Henry stories into a holiday revue with book and lyrics by Mark St. Germain. More recently, graphic novel editions emerged in the 2010s, such as the 2010 Graphic Classics Volume 19: Christmas Classics, which illustrated "The Gift of the Magi" and other seasonal tales by artists including Lisa K. Weber and Mort Todd.[70][71][72][73][74] Post-2000 recognition has revitalized interest in O. Henry's oeuvre. The Library of America issued O. Henry: 101 Stories in 2021, edited by Ben Yagoda, compiling a broad selection with annotations to highlight his stylistic range and cultural context. The 2010 centennial of his death prompted exhibitions at institutions like the Greensboro History Museum, featuring artifacts from his life. The University of Virginia Library has digitized portions of its O. Henry papers from the Doubleday archives since around 2015, making manuscripts and correspondence accessible online. Scholarly works include David Stuart's 1987 biography O. Henry: A Biography of William Sydney Porter, which examines his personal struggles including alcoholism, echoed in 2020s analyses that apply feminist perspectives to themes of gender, addiction, and social marginality in his narratives.[38][75][76][77]Bibliography

Short Story Collections

O. Henry's short stories initially appeared in magazines such as McClure's Magazine and Ainslee's Magazine starting in the early 1900s, with his first professionally published work, "Whistling Dick's Christmas Stocking," appearing in December 1899.[24] These early publications laid the groundwork for his debut collection, Cabbages and Kings (1904), published by McClure, Phillips & Co., which comprises 14 interlinked stories set in the fictional Central American republic of Anchuria, drawing from his time in Honduras.[78][30] O. Henry's productivity peaked between 1906 and 1910, during which he released several anthologies through publishers like McClure and Doubleday, Page & Co., often grouping stories thematically around urban life, the American West, or adventure. The Four Million (1906), his breakthrough collection of 25 tales depicting everyday New Yorkers, includes renowned pieces such as "The Gift of the Magi" and "The Cop and the Anthem."[78][79] The Trimmed Lamp (1907) follows with 25 stories exploring New York City's social dynamics and aspirations.[78][32] That same year, Heart of the West (1907) gathered 14 Western-themed stories inspired by his Texas experiences.[78][24] Subsequent volumes included The Gentle Grafter (1908), featuring tales of clever con artists; Roads of Destiny (1909), with 15 adventure narratives spanning various locales; Options (1909), containing 16 stories set in the American South; Strictly Business (1910), a set of 29 urban sketches; and Whirligigs (1910), compiling 23 diverse stories.[78][24] Following O. Henry's death in 1910, posthumous collections continued to assemble his unpublished and previously scattered works. Sixes and Sevens (1911), published by Doubleday, Page & Co., brought together additional stories from his final years.[78] Rolling Stones (1913), issued by Harper & Brothers, includes short stories alongside personal letters and sketches.[78] Waifs and Strays (1917), from Doubleday, Page & Co., collects remaining unanthologized pieces.[78] Later compilations, such as The Complete Works of O. Henry in the 1920s and beyond, gathered his stories into comprehensive editions.[24] Thematically, O. Henry's collections often cluster around urban realism, as in The Four Million and Strictly Business; Western frontiers, exemplified by Heart of the West; and international intrigue, like the tales in Cabbages and Kings and Roads of Destiny.[78] In 2021, the Library of America published 101 Stories, a selective anthology edited by Ben Yagoda, drawing from all periods of his career with annotations for context.[38]Poems and Non-Fiction