Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Land Ordinance of 1785

View on WikipediaThe Land Ordinance of 1785 was adopted by the United States Congress of the Confederation on May 20, 1785. It set up a standardized system whereby settlers could purchase title to farmland in the undeveloped west. Congress at the time did not have the power to raise revenue by direct taxation, so land sales provided an important revenue stream. The Ordinance set up a survey system that eventually covered over three-quarters of the area of the continental United States.[1]

The earlier Land Ordinance of 1784 was a resolution written by Thomas Jefferson calling for Congress to take action. The land west of the Appalachian Mountains, north of the Ohio River and east of the Mississippi River was to be divided into ten separate states.[2] However, the 1784 resolution did not define the mechanism by which the land would become states, or how the territories would be governed or settled before they became states. The Ordinance of 1785 put the 1784 resolution in operation by providing a mechanism for selling and settling the land,[3] while the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 addressed political needs.

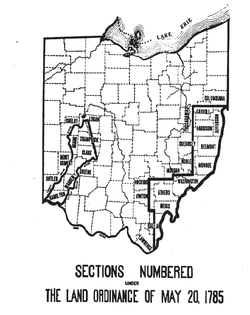

The 1785 ordinance laid the foundations of land policy until passage of the Homestead Act of 1862. The Land Ordinance established the basis for the Public Land Survey System. The initial surveying was performed by Thomas Hutchins. After he died in 1789, responsibility for surveying was transferred to the Surveyor General. Land was to be systematically surveyed into square townships, 6 mi (9.7 km) on a side, each divided into thirty-six sections of 1 sq mi (2.6 km2) or 640 acres (260 ha). These sections could then be subdivided for re-sale by settlers and land speculators.[4]

The ordinance was also significant for establishing a mechanism for funding public education. Section 16 in each township was reserved for the maintenance of public schools. Many schools today are still located in section sixteen of their respective townships,[citation needed] although a great many of the school sections were sold to raise money for public education. In later States, section 36 of each township was also designated as a "school section".[4][5][6]

The Point of Beginning for the 1785 survey was where Ohio (as the easternmost part of the Northwest Territory), Pennsylvania and Virginia (now West Virginia) met, on the north shore of the Ohio River near East Liverpool, Ohio. There is a historical marker just north of the site, at the state line where Ohio State Route 39 becomes Pennsylvania Route 68.

History

[edit]The Confederation Congress appointed a committee consisting of the following men:

- Thomas Jefferson (Virginia)

- Hugh Williamson (North Carolina)

- David Howell (Rhode Island)

- Elbridge Gerry (Massachusetts)

- Jacob Read (South Carolina)

On May 7, 1784, the people reported "An ordinance for ascertaining the mode of locating and disposing of lands in the western territories, and for other purposes therein mentioned." The ordinance required the land be divided into "hundreds of ten geographical miles square, each mile containing 6086 and 4-10ths of a foot" and "sub-divided into lots of one mile square each, or 850 and 4-10ths of an acre",[7] numbered starting in the northwest corner, proceeding from west to east, and east to west, consecutively. After debate and amendment, the ordinance was reported to Congress April 26, 1785. It required surveyors "to divide the said territory into townships seven miles square, by lines running due north and south, and others crossing these at right angles. — The plats of the townships, respectively, shall be marked into sections of one mile square, or 640 acres." This is the first recorded use of the terms "township" and "section."[8]

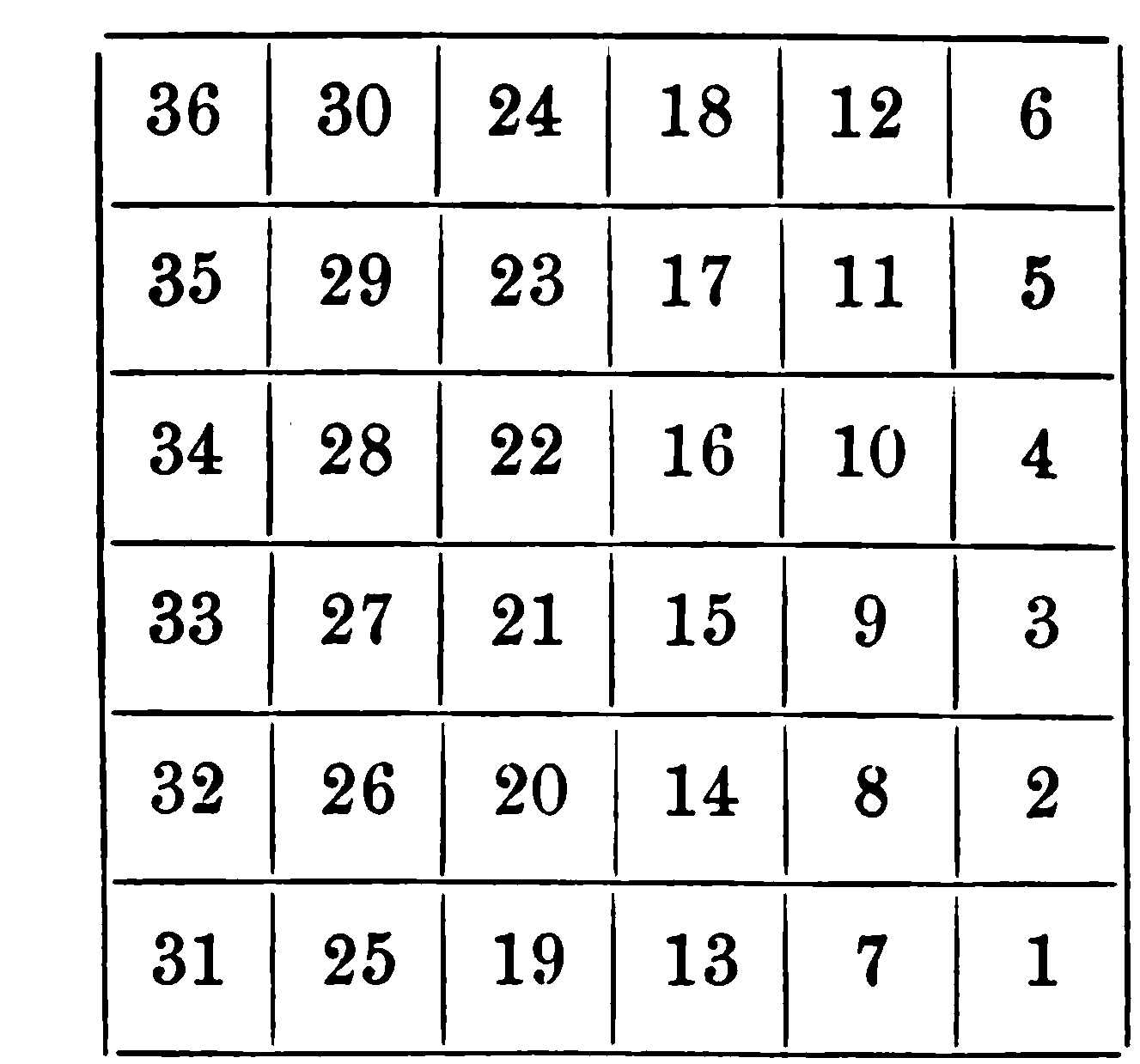

On May 3, 1785, William Grayson of Virginia made a motion seconded by James Monroe to change "seven miles square" to "six miles square." The ordinance was passed on May 20, 1785. The sections were to be numbered starting at 1 in the southeast and running south to north in each tier to 36 in the northwest. The surveys were to be performed under the direction of the Geographer of the United States (Thomas Hutchins).[8] The Seven Ranges, the privately surveyed Symmes Purchase, and, with some modification, the privately surveyed Ohio Company of Associates, all of the Ohio Lands were the surveys completed with this section numbering.[9]

The Act of May 18, 1796,[10] provided for the appointment of a surveyor-general to replace the office of Geographer of the United States, and that "sections shall be numbered, respectively, beginning with number one in the northeast section, and proceeding west and east alternately, through the township, with progressive numbers till the thirty-sixth be completed." All subsequent surveys were completed with this boustrophedonical section numbering system, except the United States Military District of the Ohio Lands which had five mile (8 km) square townships as provided by the Act of June 1, 1796,[11] and amended by the Act of March 1, 1800.[8][12]

Howe and others give Thomas Hutchins credit for conceiving the rectangular system of lots of one square mile in 1764 while a captain in the Sixtieth, or, Royal American, Regiment, and engineer to the expedition under Col. Henry Bouquet to the forks of the Muskingum, in what is now Coshocton County, Ohio. It formed part of his plan for military colonies north of the Ohio, as a protection against Indians. The law of 1785 embraced most of the new system.[13] Treat, on the other hand, notes that tiers of townships were familiar in New England, and insisted on by the New England legislators.[14]

Public education

[edit]Support for public schooling was established in the Land Ordinance through school lands[15] which granted Section 16 (one square mile) of every township to be used for public education: "There shall be reserved the Lot No. 16, of every township, for the maintenance of public schools within said township."[16][17] Section 16 was located near the center of the township. (For states surveyed under the federal rectangular system, survey townships and civil townships usually have the same boundaries, but there are many exceptions.)[18] Section 36 was also subsequently added as a school section in western states. The various states and counties ignored, altered or amended this provision in their own ways, but the general (intended) effect was a guarantee that local schools would have an income and that the community schoolhouses would be centrally located for all children.[citation needed]

The School Lands are part of the Ohio Lands,[18] comprising land grants in Ohio from the United States federal government for public schools. According to the Official Ohio Lands Book,[18] "by 1920, 73,155,075 acres of public land had been given by the federal government to the public land states in support of public schooling."

In the Land Ordinance of 1785 provision was also made by land grant for higher education (the College Lands).[citation needed]

Layout of townships

[edit]Each western township contained thirty-six square miles of land, planned as a square measuring six miles on each side, which was further subdivided into thirty-six lots, each lot containing one square mile of land. The mathematical precision of the planning was the concerted effort of surveyors. Each township contained dedicated space for public education and other government uses, as five of the thirty-six lots were reserved for government or public purposes. The thirty-six lots of each township were numbered accordingly on each township's survey. The centermost land of each township corresponded to lot numbers 15, 16, 21 and 22 on the township survey, with lot number 16 dedicated specifically to public education. As the Land Ordinance of 1785 stated: "There shall be reserved the lot No. 16, of every township, for the maintenance of public schools within the said township."[19]

Knepper notes: "Sections number 8, 11, 26, and 29 in every township were reserved for future sale by the federal government when, it was hoped, they would bring higher prices because of developed land around them. Congress also reserved one third part of all gold, silver, lead, and copper mines to its own use, a bit of wishful thinking as regards Ohio lands."[20] The ordinance also said "That three townships adjacent to Lake Erie be reserved, to be hereafter disposed of by Congress, for the use of the officers, men, and others, refugees from Canada, and the refugees from Nova Scotia, who are or may be entitled to grants of land under resolutions of Congress now existing." This was not possible, as the area next to Lake Erie was property of Connecticut, so the Canadians had to wait until the establishment of the Refugee Tract in 1798.[21]

The ordinance determined that some townships should be sold entire, and other townships should be sold by lots. It was specified that this would be done in such a way that all townships contiguous to one sold entire would be sold by lots, and vice versa. The same applied to the fractional parts of the townships.[22]

Influence

[edit]Many historians recognize the influences of the colonial experience in the land ordinances of the 1780s.[23][24] The committees that formulated these ordinances were inspired by the individual colonial experiences of the states that they represented. The committees attempted to implement the best practices of such states to solve the task at hand.[25] The surveyed townships of the Land Ordinance of 1785, writes historian Jonathan Hughes, "represented an amalgam of the colonial experience and ideals."[26] Two geographically and ideologically distinct colonial land systems were competing at such time in history – the New England system and the Southern system.[25] While the primary influence on the Land Ordinance of 1785 was the New England land system of the colonial era, marked by its emphasis on community development and systematic planning, the exceedingly individualistic Southern land system also played a role.[citation needed]

Even though Jefferson's committee had a Southern majority, it recommended the New England survey system.[27] The highly planned and surveyed western townships established in the Land Ordinance of 1785, were heavily influenced by the New England settlements of the colonial era, particularly the land grant provisions of the Ordinances which dedicated land towards public education and other government uses. In colonial times, New England settlements contained dedicated public space for schools and churches, which often held a central role in the community. For instance, the 1751 royal charter for Marlboro Vermont provides: "one Shear [share] for the First Settled Minister one Shear for the benefit of the School forever."[28] By the time the Land Ordinance of 1785 was enacted, the New England states had used land grants for over a century to support public education and build new schools. The clause in the Land Ordinance of 1785 which dedicated "Lot Number 16" of each western township for public education reflected this regional New England experience.[29]

In addition, the use of surveyors to precisely chart out the new townships in the westward expansion was directly influenced by the New England land system, which similarly relied on surveyors and local committees to clearly delineate property boundaries. Defined property boundary lines and an established land title system, provided colonials with a sense of security in their land ownership, by minimizing the likelihood of ownership or boundary disputes. This was an important consideration in the Land Ordinance of 1785. One of the primary purposes of the Ordinance was to raise funds for the increasingly insolvent government. Providing land speculators security in their purchases encouraged additional demand for the western lands. In addition, the organized and communal nature of the western settlements, allowed the government to reserve a number of well-defined plots of land for future government development. Since the rest of the township would have been developed by the time the government decided to develop such reserved lands, there was an already built-in assurance of land value appreciation for the reserved lands. This had the effect of increasing the value of government assets without much further investment by the government.[citation needed]

The New England land system, while the primary influence on the great land ordinances of the 1780s, was not the only land system influence. The Southern land system, marked by individualism and personal initiative, also helped shape the ordinance. While the New England land system was premised on community-based development, the Southern land system was premised on individual frontiersman appropriating undeveloped land to call their own. The Southern pioneer claimed property and the local surveyor would demarcate it for him. The system did not protect people from competing claims or set up an orderly chain of title. The process was called 'indiscriminate location". This system encouraged individuals to amass large plantations instead of settling into dense communal development. This system was supported by the use of slave labor.[30] Perhaps the committee's resistance against indiscriminate location and support for limited and disciplined land settlement was an implicit attempt to create a structural barrier to developing a plantation economy that was dependent on slave labor. The committee could have been attempting to effectively eradicate slavery in the West after Jefferson failed to outlaw it in the Land Ordinance of 1784.[citation needed]

While the Land Ordinance of 1785 created a New England style land system, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 determined how the townships would be administered. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787, like the Land Ordinance of 1785, was inspired by the New England colonial settlements, and manifested this influence by further encouraging the worship of religion and the spread of education. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 stated, "Religion, morality, and knowledge being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged."[31] However, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 also contained Southern characteristics of municipal governance. The Southern influence can be felt in the Western townships in that once the federal land was dedicated to the particular township, the township was relatively free of the influence of the federal government, and the local municipality was left to govern itself. This manifested itself in public education as well. Once the land was dedicated, the actual development of the public schools was the responsibility of the local township or the particular state.[32] Although the great Ordinances of the 1780s set the framework for a national system of schools by dedicating land across the West, the devolved development and administration by the state and local government led to unique results.[33]

Motives

[edit]Retaining central land in each township ensured that these lands would create value for the federal government and the safety of the people. Instead of disbursing funds to the new states to create public education systems, dedicating a central lot in each township provided the new townships with the means to develop educational institutions without any transfer of funds. This was a practical and necessary way to achieve the committee's goal in a pre-Constitution America. Aside from raising funds for a financially struggling government, the westward expansion outlined in the Land Ordinances of the 1780s also provided a framework for spreading democratic ideals. Jefferson proposed an article in the Ordinance that would have outlawed slavery in the new states after the year 1800. However he could not amass enough votes to pass the anti-slavery article. Later Jefferson did succeed, however, in ensuring public funding of education by dedicating land to education in the Land Ordinance of 1785. Public education was an ideal already developed in the New England colonial settlements. New Englanders provided for public education in their land grants due to a belief that public education could be used to further unite the young nation and spread democratic ideals.[29]

The systematic and highly organized westward settlements, with their local governments and central square dedicated towards public education, were a concerted effort to inspire civic duty and participation in the democratic process. Usher relates this initiative to "the Supreme Court in Cooper v. Roberts (1855), 'plant in the heart of every community the same sentiments of grateful reverence for the wisdom, forecast, and magnanimous statesmanship of those who framed the institutions of these new States."[34] The westward expansion therefore was not only a tool for raising much needed funds, but also a tool in a grand socializing experiment to inoculate the settlers to democratic ideals. The hope was that the unique planning of each township with a public school centrally located, coupled with the obligation of each township's local citizens to take part in the civic process of governing the township, teaching and building the schools, and maintaining order, would instill the democratic ideals crucial to the nation's success.

Criticism

[edit]The economist Murray Rothbard wrote a critical review of George B. DeHuszar and Thomas Hulbert Stevenson, ' A History of the American Republic, 2 vols ' in which he states that the authors failed to realise that the handing over of western lands to the federal government resulted in huge unearned property to the federal government's unearned "public domain":

The Ordinance of 1785 was a dictatorial intrusion into the western region, which set too high a minimum land sale and price, thus restricting settlement, and also enforced rectangular surveying, thus forcing the purchase of submarginal land within an otherwise good “rectangle,” instead of conforming, as in the Southern methods of surveying, to the natural topography of the land in question. In colonial days, unowned land was free to all settlers, and this represented a sharp change in the direction of étatist restriction of land settlement and increasing government revenue from land. DeHuszar shows no sign of realizing this significance of the ordinance. Furthermore, the Ordinance of 1785 foisted public schools upon each township in the region, thus taking the first step toward public schools and toward federal dictation over education. None of this seems to impress DeHuszar or dampen his enthusiasm for the ordinance.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Carstensen, Vernon (1987). "Patterns on the American Land". Journal of Federalism. 18 (4): 31–39.

- ^ McCormick, Richard P. (January 1993). "The 'Ordinance' of 1784?". William and Mary Quarterly. 50 (1): 112–122.

- ^ "An ordinance for ascertaining the mode of disposing of Lands in the Western Territory". Journal of Continental Congress. 28: 375. May 20, 1785 – via Library of Congress.

- ^ a b White, C. Albert (1983), A History of the Rectangular Survey System, Bureau of Land Management[page needed]

- ^ Williamson & Donaldson 1880, p. 226.

- ^ The Oregon Territory Act (August 14, 1848) 9 Stat. 323 initiated practice of setting aside section 36 for schools: Section 20 "And be it further enacted, That when the lands in the said Territory shall be surveyed under the direction of the Government of the United States, preparatory to bringing the same into market, sections numbered sixteen and thirty-six in each township in said Territory shall be, and the same is hereby, reserved for the purpose of being applied to schools in said Territory, and in the States and Territories hereafter to be erected out of the same."

- ^ "An ordinance for ascertaining the mode of locating and disposing of lands in the western territory". Journal of Continental Congress. 27: 446. May 28, 1784 – via Library of Congress.

- ^ a b c Higgins 1887, pp. 33–34, 78–82.

- ^ Peters 1918 : 58

- ^ 1 Stat. 464 – Text of Act of May 18, 1796 Library of Congress

- ^ 1 Stat. 490 – Text of Act of June 1, 1796 Library of Congress

- ^ 2 Stat. 14 – Text of Act of March 1, 1800 Library of Congress

- ^ Howe 1907 : 134

- ^ Treat 1910, pp. 179–182.

- ^ A compilation of laws, treaties, resolutions, and ordinances: of the general and state governments, which relate to lands in the state of Ohio; including the laws adopted by the governor and judges; the laws of the territorial legislature; and the laws of this state, to the years 1815-16. G. Nashee, State Printer. 1825. pp. 534. page 17.

- ^ "Ohio Lands: A Short History Part 5". Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ John Kilbourne (1907). "The Public Lands of Ohio". In Henry Howe (ed.). Historical Collections of Ohio ... an Encyclopedia of the State. Vol. 1 (The Ohio Centennial ed.). The State of Ohio. School lands, page 132. (Volume 1 originally published in 1847 as Historical Collections of Ohio.)

- ^ a b c George W. Knepper. "The Land Ordinance of 1785" (PDF). The Official Ohio Lands Book. Retrieved 10 March 2011. page 56.

- ^ "PublicEducationInLandGrantsSGrenbaum - AmLegalHist - TWiki".

- ^ Knepper 2002 : 9

- ^ Knepper 2002 : 51

- ^ United States; King, Rufus; Johnson, William Samuel; Continental Congress Broadside Collection (Library of Congress), eds. (1785). An ordinance for ascertaining the mode of disposing of lands in the Western Territory: Be it ordained by the United States in Congress assembled, that the territory ceded by individual states to the United States, which has been purchased of the Indian inhabitants, shall be disposed of in the following manner. [New York: s.n.

- ^ Treat 1910.

- ^ Hughes, Jonathan (1987). "The Great Land Ordinances: Colonial America's Thumbprint on History" (PDF). In Klingaman, David C.; Vedder, Richard K. (eds.). Essays on the Economy of the Old Northwest. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-0875-9. Retrieved 15 March 2013 – via Minnesota Legal History Project.

- ^ a b Treat 1910, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Hughes 1987, p. 11.

- ^ Treat 1910, p. 26.

- ^ Hughes 1987, p. 13.

- ^ a b Carleton, David (2002). Landmark Congressional Laws on Education. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-313-31335-6.

- ^ Treat 1910, p. 25.

- ^ The Northwest Ordinance of 1787, Article 3, retrieved 15 March 2013

- ^ Usher, Alexandra (April 2011), Public Schools in the Original Federal Land Grant Program (PDF), The Center on Education Policy, p. 8

- ^ Usher 2011, p. 8.

- ^ Usher 2011, p. 7.

- ^ Rothbard, Murray (2010). Strictly Confidential: The Private Volker Fund Memos of Murray N. Rothbard (PDF). Mises Institute. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-933550-80-0.

References and further reading

[edit]- Higgins, Jerome S. (1887). Subdivisions of the Public Lands, Described and Illustrated, with Diagrams and Maps. Higgins & Co.

- Howe, Henry (1907). Historical Collections of Ohio, The Ohio Centennial Edition. Vol. 1. The State of Ohio. ISBN 9781404753761.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Knepper, George W (2002). The Official Ohio Lands Book (PDF). State of Ohio.

- Peters, William E (1918). Ohio Lands and Their Subdivision. W.E. Peters. p. 58.

- Treat, Payson Jackson (1910). The National Land System 1785–1820. E.B. Treat and Co. p. 179.

- Williamson, James Alexander; Donaldson, Thomas (1880). The Public Domain. Its History, with Statistics. Government Printing Office. p. 226.

- Johnson, Hildegard Binder. Order upon the Land: The U.S. Rectangular Land Survey and the Upper Mississippi Country (1977)

- Geib, George W.. "The Land Ordinance of 1785: A Bicentennial Review," Indiana Magazine of History, March 1985, Vol. 81 Issue 1, pp 1–13

External links

[edit]Land Ordinance of 1785

View on GrokipediaHistorical Context and Enactment

Origins in Post-Revolutionary Land Claims

The resolution of conflicting state claims to western territories following the Revolutionary War formed the foundational impetus for federal land policy under the Articles of Confederation. Colonial charters had granted expansive western claims to states such as Virginia, New York, and Massachusetts, extending to the Mississippi River, but these overlapped and excluded landless states like Maryland, which withheld ratification of the Articles until claimant states agreed to cede lands to Congress for disposal as a common national resource to service war debts.[7][8] New York acted first, executing a deed of cession on March 1, 1781, transferring its claims north of Pennsylvania and south of the Great Lakes to federal control.[9] This paved the way for Maryland's ratification on February 2, 1781, completing the Confederation and shifting focus to securing further cessions.[10] Virginia's claim, the largest encompassing the Northwest Territory north of the Ohio River, proved pivotal; after initial reluctance and conditional offers in 1781, its General Assembly enacted a cession on December 20, 1783—excluding reserved military bounty lands totaling about 4.2 million acres—which Congress formally accepted on March 1, 1784.[11][12] Subsequent cessions from Massachusetts in 1785 and Connecticut in 1786 completed the transfers, vesting Congress with title to approximately 236 million acres of public domain by 1786.[7] These acquisitions transformed the western lands from disputed state assets into a federal endowment, but unmanaged settlement risked anarchy, speculation fraud, and Indian conflicts, compelling Congress to devise structured administration rather than ad hoc sales.[13] The post-cession vacuum in policy—exacerbated by the failure of the 1784 Ordinance's vague division into ten districts without surveying mechanisms—necessitated the 1785 Ordinance's emphasis on rectangular surveys prior to auction, directly applied to Virginia's ceded territory to ensure orderly expansion and revenue, yielding initial sales proceeds of $1,200 from the first Ohio survey tract in 1787.[14][15] This approach reflected causal priorities of fiscal solvency, with land sales projected to fund 60-70% of Confederation debts, while preempting private encroachments that had plagued earlier colonial grants.[16]Legislative Process and Key Figures

The Confederation Congress, operating under the Articles of Confederation, initiated the legislative process for the Land Ordinance of 1785 to address the urgent need for revenue from western lands ceded by states, building on the inconclusive Ordinance of 1784 which had outlined territorial division but lacked a practical surveying mechanism.[17] In March 1785, amid fiscal pressures from war debts exceeding $40 million, Congress appointed a three-member committee—William Grayson of Virginia, Rufus King of Massachusetts, and William Ellery of Rhode Island—to devise a systematic approach to land surveys facilitating orderly sales.[18] Grayson, serving as committee chair, led the drafting, with the group reporting its plan on April 12, 1785, proposing a grid-based system of six-mile-square townships subdivided into 640-acre sections to enable precise auctions and minimize disputes over irregular boundaries seen in eastern states.[18] Debates ensued over minimum lot sizes (initially one township, later reduced to sections), pricing at one dollar per acre, and reservations like the sixteenth section for public schools, reflecting compromises between revenue maximization and settlement incentives. The measure underwent two revisions, with the third draft incorporating these changes to balance federal authority against state interests.[19] The ordinance passed unanimously on May 20, 1785, marking a pivotal assertion of national control over public domain lands northwest of the Ohio River.[3] Key figures included Grayson, whose report shaped the core surveying framework; King, who advocated for structured expansion to prevent speculative chaos; and Ellery, contributing to provisions ensuring surveyed lands preceded settlement. Their work embodied first-principles prioritization of geometric efficiency for causal scalability in land administration, overriding haphazard claims that had fueled colonial conflicts.[18]Core Provisions and Survey System

Rectangular Survey Framework

The Rectangular Survey Framework, authorized by the Land Ordinance of 1785 enacted on May 20, 1785, introduced a systematic rectangular grid for subdividing public domain lands in the western territories, primarily the Northwest Territory ceded to the United States following the Revolutionary War.[20] This approach diverged from traditional metes-and-bounds surveying by imposing a uniform coordinate system of north-south meridians and east-west parallels intersected at right angles, enabling precise measurement and allocation of land parcels before settlement or sale.[20] The framework mandated that qualified surveyors, under the direction of a Geographer appointed by Congress, divide the territory into townships six miles square using chains for linear measurement and compasses aligned to true meridians.[3] Initial lines originated from a designated point on the Ohio River due north of Pennsylvania's western boundary, with the first north-south line extending from there and perpendicular east-west lines forming the grid's foundational structure.[21] Each township encompassed 23,040 acres, subdivided into 36 sections of one square mile each, equivalent to 640 acres, with boundaries marked by posts, mounds, or bearing trees and recorded in detailed field notes including topography, soil, and landmarks.[20] Sections were further divisible into quarter-sections of 160 acres via lines connecting midpoints of section sides, promoting equitable distribution for auction sales.[20] The system prioritized exterior township boundaries in initial surveys, deferring internal section lines until necessary, to expedite platting and revenue generation while minimizing fieldwork errors through double chaining and corrections limited to three chains per mile.[20] Thomas Hutchins, the first Geographer of the United States, oversaw early implementation, commencing fieldwork on September 30, 1785, in the Seven Ranges along the Ohio River.[20] This grid-based methodology ensured land titles were based on fixed, verifiable coordinates rather than variable natural features, reducing disputes and facilitating national expansion under federal control.[1] Subsequent refinements, such as correction lines every 24 to 60 miles to account for Earth's curvature and guide meridians for alignment, built upon the 1785 foundation but were not part of the original ordinance.[20] By standardizing divisions, the framework supported minimum pricing at one dollar per acre for whole sections, with lot 16 in each township reserved for public schools, embedding provisions for education within the survey design.[3]Township and Section Division

The Land Ordinance of 1785 mandated that surveyed lands be organized into townships measuring six miles by six miles, yielding an area of 36 square miles per township.[5] Each township was subdivided into 36 sections, with each section comprising one square mile or 640 acres, to standardize land parcels for auction and settlement.[5][22] Sections within a township were numbered in a systematic vertical pattern, commencing with section 1 at the southeast corner and extending northward to section 6 at the northeast corner along the easternmost tier.[22][23] The adjacent tier to the west followed suit, numbering from section 7 at its southern end to section 12 at the northern end, with this south-to-north progression continuing westward across six tiers until section 36 at the northwest corner.[22][24] This columnar numbering scheme, distinct from later horizontal boustrophedon adaptations, supported orderly demarcation during initial surveys like those of the Seven Ranges in Ohio.[22][25] Certain sections received specific reservations to promote public welfare and future allocations. Section 16 in every township was designated for the maintenance of public schools within that township. Sections 8, 11, 26, and 29 were reserved for disposal by the United States Congress, typically intended for religious societies or other public purposes as determined later. These provisions embedded educational and communal priorities into the grid system from its inception.[5]Sales Mechanisms and Pricing

The Land Ordinance of 1785 established a system for selling public lands in the Northwest Territory through public auctions, or vendues, conducted by commissioners appointed from the loan offices of the states. These auctions required advance notice of two to six months, disseminated via postings at county courthouses and advertisements in newspapers within the commissioners' states of residence. Lands were offered starting with the townships nearest the Ohio or Pennsylvania borders, progressing westward, with sales prioritized for surveyed areas to generate revenue for the federal government.[3][14] Sales units consisted of entire townships, fractional townships, or individual sections of 640 acres, with the minimum tract size being one section when subdivided. In the first range of townships, sales alternated between entire townships and lots (sections), with subsequent ranges following similar patterns to balance large-scale and smaller purchases. A fixed administrative fee of $36 applied per township, prorated for fractions or lots, payable at the time of sale. Failure to complete payment resulted in resale at the next auction, with the defaulting purchaser liable for any shortfall.[3][14] Pricing was set at a statutory minimum of one dollar per acre, prohibiting sales below this threshold to ensure fiscal returns while allowing competitive bidding to potentially exceed it. This minimum applied uniformly across offered units, reflecting the Confederation Congress's aim to value land based on its surveyed quality without speculative undercutting.[3][14] Payments were accepted in specie, loan-office certificates adjusted to specie value via the depreciation scale, or certificates for liquidated United States debts including accrued interest, facilitating participation by holders of revolutionary war securities. This mechanism aimed to absorb outstanding federal obligations but limited accessibility for small farmers lacking cash or certificates, contributing to initially low sales volumes despite the structured process.[3][14]Implementation and Administration

Initial Surveying Efforts

The initial surveying under the Land Ordinance of 1785 began shortly after its enactment on May 20, 1785, with Congress directing the Geographer of the United States to oversee the process prior to any land sales.[1] Thomas Hutchins, appointed to this role in 1785, led the first federal efforts to implement the rectangular survey system in the Northwest Territory, starting with the area north of the Ohio River.[5] On September 30, 1785, Hutchins established the "Point of Beginning" by driving a stake into the north bank of the Ohio River, located at approximately 40 degrees 38 minutes north latitude and about 5 degrees west of Pennsylvania's southern boundary line, near modern-day East Liverpool, Ohio.[26][27] This meridian served as the initial reference for dividing lands into townships and sections, marking the origin of the Public Land Survey System.[28] Survey teams under Hutchins commenced fieldwork in late 1785, focusing first on the "Seven Ranges"—an area comprising seven six-mile-wide strips of townships extending northward from the Ohio River between the Cuyahoga and Tuscarawas rivers in present-day northeastern Ohio.[5] Using chains, compasses, and astronomical observations for accuracy, surveyors marked township boundaries with mounds of earth and wooden posts, subdividing each 36-square-mile township into 36 one-square-mile sections numbered in a boustrophedon pattern starting from the southeast corner.[26] The work progressed eastward from the Point of Beginning, with the first range completed by early 1786 despite rudimentary tools and limited manpower—typically crews of a few deputies and axe-men.[29] By 1787, the Seven Ranges surveys were substantially finished, enabling the first public land auctions, though full precision required later adjustments due to instrumental errors and terrain variations.[5] These efforts faced significant obstacles, including seasonal flooding, dense forests, and intermittent conflicts with Native American tribes who viewed the surveys as encroachments on unceded lands, leading to occasional harassment of survey parties.[27] Hutchins documented these challenges in field journals, noting delays from weather and the need for military escorts in some areas, yet the surveys established a durable grid that minimized boundary disputes compared to irregular colonial methods.[26] The completion of the initial ranges demonstrated the feasibility of the ordinance's system, generating plats that Congress used for sales starting in 1787 at New York, though actual settlement lagged due to ongoing territorial disputes.[1] Hutchins continued directing expansions until his death in 1789, after which the Surveyor General's office assumed oversight.[5]Revenue Generation and Sales Practices

The Land Ordinance of 1785 generated federal revenue primarily through public auctions of surveyed lands in the Northwest Territory, conducted after rectangular surveys divided territories into townships and sections.[3] Commissioners from state loan offices oversaw sales of townships or fractional parts at public vendue to the highest bidder, with lands offered in a prescribed sequence of sections to facilitate orderly disposition.[3][14] Minimum bids were set at one dollar per acre, payable immediately in specie, loan-office certificates discounted to their specie value, or certificates for liquidated public debts including accrued interest, plus reimbursement for survey costs such as thirty-six dollars per township.[3] The smallest purchasable unit was one section of 640 acres or multiples thereof, excluding reserved sections for public purposes, which deterred small-scale farmers and favored land speculators capable of large investments.[3][14] Sales occurred in eastern cities like New York, with unsold portions after eighteen months returned to the Board of Treasury for reoffering.[3] Initial auctions, commencing in October 1787, produced modest revenue of approximately $176,090 from over 100,000 acres sold, though roughly one-third of that acreage was forfeited due to purchaser defaults on payments.[18] Factors limiting sales volume included the territory's remoteness, persistent Native American resistance to encroachment, lack of extended credit, and the high minimum purchase size, resulting in dominance by absentee investors rather than immediate settlers.[14][1] These practices prioritized fiscal returns over rapid population expansion, yielding limited short-term funds for the cash-strapped Confederation government amid its inability to levy direct taxes.[30] Subsequent legislation, such as the Land Act of 1796, addressed these constraints by reducing minimum lots to 320 acres and introducing four-year credit terms to enhance revenue through broader participation.[1]