Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Braddock Expedition

View on Wikipedia| Braddock Expedition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French and Indian War | |||||||

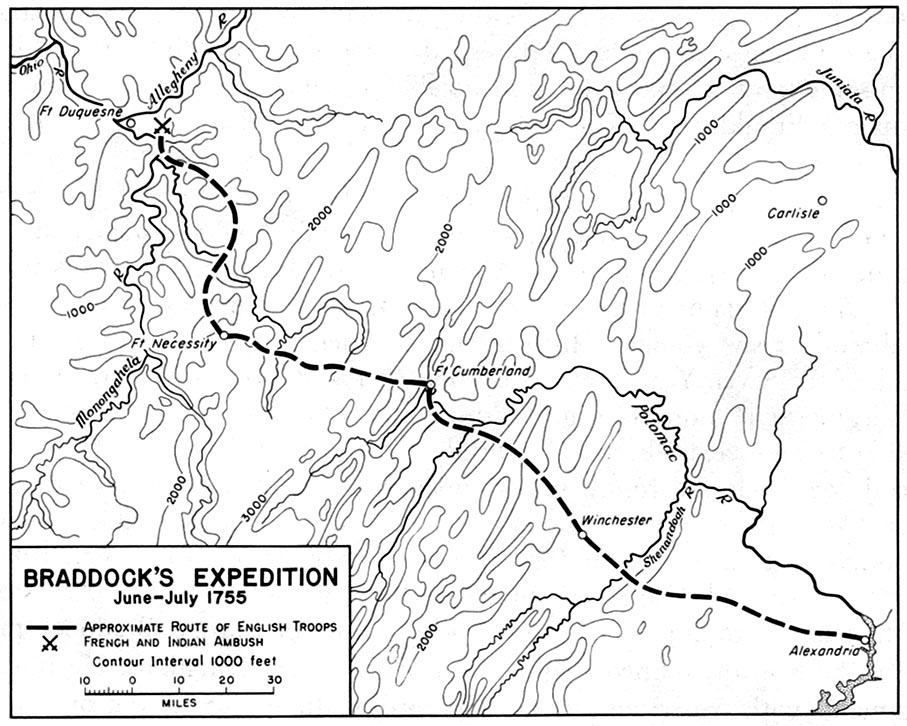

Route of the Braddock Expedition | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Native Americans | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

637 natives, 108 French marines 146 Canadian militia[1] |

2,100 regular and provincials 10 cannon[1][2][3][need quotation to verify] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

30 killed 57 wounded[1] |

500+ killed[1] 450+ wounded[4] | ||||||

| Designated | November 3, 1961[5] | ||||||

| |||||||

The Braddock Expedition, also known as Braddock's Campaign or Braddock's Defeat, was a British military expedition which attempted to capture Fort Duquesne from the French in 1755 during the French and Indian War. The expedition, named after its commander General Edward Braddock, was defeated at the Battle of the Monongahela on July 9 and forced to retreat; Braddock was killed in action along with more than 500 of his troops. It ultimately proved to be a major setback for the British in the early stages of the war, one of the most disastrous defeats suffered by British forces in the 18th century.[6]

Background

[edit]Braddock's expedition was part of a massive British offensive against the French in North America that summer. As commander-in-chief of the British Army in America, General Edward Braddock led the main thrust against the Ohio Country with a column some 2,100 strong. His command consisted of two regular line regiments, the 44th and 48th, in all 1,400 regular soldiers and 700 provincial troops from several of the Thirteen Colonies, and artillery and other support troops. With these men, Braddock expected to seize Fort Duquesne easily, and then push on to capture a series of French forts, eventually reaching Fort Niagara. George Washington, promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel of the Virginia Regiment on June 4, 1754, by Governor Robert Dinwiddie,[7] was then just 23, knew the territory and served as a volunteer aide-de-camp to General Braddock.[8] Braddock's Chief of Scouts was Lieutenant John Fraser of the Virginia Regiment. Fraser owned land at Turtle Creek, had been at Fort Necessity, and had served as Second-in-Command at Fort Prince George (replaced by Fort Duquesne by the French), at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers.

Braddock mostly failed in his attempts to recruit Native American allies from those tribes not yet allied with the French; he had but eight Mingo Indians with him led by George Croghan, serving as scouts. A number of Native Americans in the area, notably Delaware leader Shingas, remained neutral. Caught between two powerful European empires at war, the local Native Americans could not afford to be on the side of the loser. They would decide based on Braddock's success or failure.

Expedition strength

[edit]According to returns given June 8, 1755, at the encampment at Will's Creek.

- His Majesty's Troops

| Regiment | Officers present | Staff present | Sergeants present | Drummers and effectives present | Wanting to complete the establishment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 44th Foot | 33 | 5 | 30 | 790 | 280 |

| 48th Foot | 34 | 5 | 30 | 704 | 366 |

| Capt. John Rutherford's Independent Company, New York | 4 | 1 | 3 | 93 | – |

| Capt. Horatio Gates's Independent Company, New York | 4 | 1 | 3 | 93 | – |

| Detachment from South Carolina, commanded by Capt. Paul Demeré | 4 | 0 | 4 | 102 | – |

| Source:[9] |

Detachement under Capt. Robert Hind

| Military branch present | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Officers | Surgeon | Sergeants | Corporals and Bombardiers | Gunners | Matrosses | Drummer | Total |

| 7 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 18 | 32 | 1 | 70 |

| Civil branch present | |||||||

| Wagon master | Master of Horse | Commissary | Assistant Commissary | Conductors | Artificers | N/A | Total |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 12 | n/a | 22 |

| Source:[9] | |||||||

| Troop or Company | Officers present | Staff present | Sergeants present | Drummers and effectives present | Wanting to complete the establishment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capt. Robert Stewart's Virginia Light Horse | 3 | 0 | 2 | 33 | – |

| Capt. George Mercer's Virginia Artificers | 3 | 0 | 3 | 42 | 11 |

| Capt. William Polson's Virginia Artificers | 3 | 0 | 3 | 50 | 3 |

| Capt. Adam Stevens's Virginia Rangers | 3 | 3 | 3 | 53 | – |

| Capt. Peter Hogg's Virginia Rangers | 3 | 0 | 3 | 42 | 11 |

| Capt. Thomas Waggoner's Virginia Rangers | 3 | 0 | 3 | 53 | – |

| Capt. Thomas Cocke's Virginia Rangers | 3 | 0 | 3 | 47 | 6 |

| Capt. William Perronée's Virginia Rangers | 3 | 0 | 3 | 52 | 1 |

| Capt. John Dagworthy's Maryland Rangers | 3 | 0 | 3 | 53 | – |

| Capt. Edward Brice Dobb's North Carolina Company | 3 | 0 | 3 | 72 | 28 |

| Source:[9] |

Expedition

[edit]

Setting out from Fort Cumberland in Maryland on May 29, 1755, the expedition faced an enormous logistical challenge: moving a large body of men with equipment, provisions, and (most importantly, for attacking the forts) heavy cannons, across the densely wooded Allegheny Mountains and into western Pennsylvania, a journey of about 110 miles (180 km). Braddock had received important assistance from Benjamin Franklin, who helped procure wagons and supplies for the expedition. Among the wagoners were two young men who would later become legends of American history: Daniel Boone and Daniel Morgan. Other members of the expedition included Ensign William Crawford and Charles Scott. Among the officers of the expedition were Thomas Gage, Charles Lee, future American president George Washington, and Horatio Gates.

Braddock's Road

[edit]The expedition progressed slowly because Braddock considered making a road to Fort Duquesne a priority in order to effectively supply the position he expected to capture and hold at the Forks of the Ohio, and because of a shortage of healthy draft animals. In some cases, the column was only able to progress at a rate of two miles (about 3 km) a day, creating Braddock's Road — an important legacy of the march — as they went. To speed up movement, Braddock split his men into a "flying column" of about 1,300 men which he commanded, and, lagging far behind, a supply column of 800 men with most of the baggage, commanded by Colonel Thomas Dunbar. They passed the ruins of Fort Necessity along the way, where the French and Canadians had defeated Washington the previous summer. Small French and Native American war bands skirmished with Braddock's men during the march.

Meanwhile, at Fort Duquesne, the French garrison consisted of only about 250 French marines and Canadian militia, with about 640 Native American allies camped outside the fort. The Native Americans were from a variety of tribes long associated with the French, including Ottawas, Ojibwas, and Potawatomis. Claude-Pierre Pécaudy de Contrecœur, the Canadian commander, received reports from Native American scouting parties that the British were on their way to besiege the fort. He realised he could not withstand Braddock's cannon, and decided to launch a preemptive strike, an ambush of Braddock's army as he crossed the Monongahela River. The Native American allies were initially reluctant to attack such a large British force, but the French field commander Daniel Liénard de Beaujeu, who dressed himself in full war regalia complete with war paint, convinced them to follow his lead.

Battle of the Monongahela

[edit]

By July 8, 1755, the Braddock force was on the land owned by the Chief Scout, Lieutenant John Fraser. That evening, the Native Americans sent delegates to the British to request a conference. Braddock chose Washington and Fraser as his emissaries. The Native Americans asked the British to halt their advance, claiming that the French could be persuaded to peacefully leave Fort Duquesne. Both Washington and Fraser recommended that Braddock approve the plan, but he demurred.

On July 9, 1755, Braddock's men crossed the Monongahela without opposition, about 10 miles (16 km) south of Fort Duquesne. The advance guard of 300 grenadiers and colonials, accompanied by two cannon, and commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Gage began to move ahead. Washington tried to warn Braddock of the flaws in his plan — such as pointing out that the French and the Native Americans fought differently than the open-field style used by the British -- but his efforts were ignored: Braddock insisted that his troops fight as "gentlemen". Then, unexpectedly, Gage's advance guard came upon Beaujeu's party of French and Native Americans, who were hurrying to the river, behind schedule and too late to prepare an ambush.

In the skirmish that followed between Gage's soldiers and the French, Beaujeu was among those killed by the first volley of musket fire by the grenadiers. Although some 100 French Canadians fled back to the fort and the noise of the cannon held the Native Americans off, Beaujeu's death did not have a negative effect on French morale. Jean-Daniel Dumas, a French officer, rallied the rest of the French and their Native American allies. The battle, known as the Battle of the Monongahela, or the Battle of the Wilderness, or just Braddock's Defeat, was officially begun. Braddock's force was approximately 1,400 men. The British faced a French and Native American force estimated to number between 300 and 900. The battle, frequently described as an ambush, was actually a meeting engagement, where two forces clash at an unexpected time and place. The quick and effective response of the French and Native Americans — despite the early loss of their commander — led many of Braddock's men to believe they had been ambushed. However, French battle reports state that while an ambush had been planned, the sudden arrival of the British forced a direct confrontation.

After an exchange of fire, Gage's advance group fell back. In the narrow confines of the road, they collided with the main body of Braddock's force, which had advanced rapidly when the shots were heard. The entire column dissolved in disorder as the Canadian militiamen and Native Americans enveloped them and began firing from the dense woods on both sides. At this time, the French marines began advancing from the road and blocked any attempt by the British to move forward.

Following Braddock's example, the officers kept trying to form their men into standard battle lines so they could fire in formation - a strategy that did little but make the soldiers easy targets. The artillery teams tried to provide covering fire, but there was no space to load the pieces properly and the artillerymen had no protection from enemy sharpshooters. The provincial troops accompanying the British eventually broke ranks and ran into the woods to engage the French; confused by what they thought were enemy reinforcements, panicking British regulars started mistakenly firing on the provincials. After several hours of intense combat, Braddock was fatally shot off his horse, and effective resistance collapsed. Washington, although he had no official position in the chain of command, was able to impose and maintain some order. He formed a rear guard, which allowed the remnants of the force to disengage. This earned him the sobriquet Hero of the Monongahela, by which he was toasted, and established his fame for some time to come.

We marched to that place, without any considerable loss, having only now and then a straggler picked up by the French and scouting Indians. When we came there, we were attacked by a party of French and Indians, whose number, I am persuaded, did not exceed three hundred men; while ours consisted of about one thousand three hundred well-armed troops, chiefly regular soldiers, who were struck with such a panic that they behaved with more cowardice than it is possible to conceive. The officers behaved gallantly, in order to encourage their men, for which they suffered greatly, there being near sixty killed and wounded; a large proportion of the number we had.

— George Washington, July 18, 1755, letter to his mother.[10]

Aftermath

[edit]

By sunset, the surviving British forces were retreating back down the road they had built. Braddock died of his wounds during the long retreat, on July 13, and is buried within the Fort Necessity parklands. Of the approximately 1,300 men Braddock had led into battle, 456 were killed and 422 wounded. Commissioned officers were prime targets and suffered greatly: out of 86 officers, 26 were killed and 37 wounded. Of the 50 or so women that accompanied the British column as maids and cooks, only 4 survived. The French and Canadians reported 8 killed and 4 wounded; their Native American allies lost 15 killed and 12 wounded.

Colonel Dunbar, with the reserves and rear supply units, took command when the survivors reached his position. He ordered that excess supplies and cannons should be destroyed before withdrawing, burning about 150 wagons on the spot. Ironically, at this point the defeated, demoralized and disorganised British forces still outnumbered their opponents. The French and Native Americans did not pursue; they were far too busy looting dead bodies and collecting scalps. The French commander, Dumas, realized Braddock's army was utterly defeated. Yet, to avoid upsetting his men, he did not attempt any further pursuit.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Borneman, Walter R. (2007). The French and Indian War. Rutgers. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-06-076185-1.

French: 28 killed 28 wounded, Indian: 11 killed 29 wounded

- ^ History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, Duncan, Major Francis, London, 1879, Vol. 1, p. 58, Fifty Royal Artillerymen, 4 brass 12 pounders, 6 brass 6 pounders, 21 civil attendants, 10 servants and six "necessary women".

- ^ John Mack Faragher, Daniel Boone, the Life and Legend of an American Pioneer, Henry Holt and Company LLC, 1992, ISBN 0-8050-3007-7, p. 38.

- ^ Frank A. Cassell. "The Braddock Expedition of 1755: Catastrophe in the Wilderness". Archived from the original on December 31, 2010. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ "PHMC Historical Markers Search". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original (Searchable database) on March 21, 2016. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^

Faragher, John Mack (1993) [1992]. "Curiosity is Natural: 1734 to 1755". Daniel Boone: The Life and Legend of an American Pioneer. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 38. ISBN 978-1429997065. Retrieved March 18, 2022.

The Battle of the Monongahela [...] was one of the bloodiest and most disastrous British defeats of the eighteenth century.

- ^ Longmore, The Invention of George Washington, University of Virginia Press, 1999, p. 20

- ^ Some accounts state that Washington commanded the regiment on the Braddock Expedition, but this is incorrect. Washington did command the Virginia Regiment before and after the expedition. As a volunteer aide-de-camp, Washington essentially served as an unpaid and unranked gentleman consultant, with little real authority, but much inside access.

- ^ a b c Pargellis, Stanley (1936). Military Affairs in North America 1748–1765. The American Historical Association, pp. 86–91.

- ^ Similarly, Washington's report to Governor Dinwiddie. Charles H. Ambler, George Washington and the West, University of North Carolina Press, 1936, pp. 107–109.

Further reading

[edit]- Chartrand, Rene. Monongahela, 1754–1755: Washington's Defeat, Braddock's Disaster. United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-84176-683-6.

- Jennings, Francis. Empire of Fortune: Crowns, Colonies, and Tribes in the Seven Years War in America. New York: Norton, 1988. ISBN 0-393-30640-2.

- Kopperman, Paul E. Braddock at the Monongahela. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1973. ISBN 0-8229-5819-8.

- O'Meara, Walter. Guns at the Forks. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1965. ISBN 0-8229-5309-9.

- Preston, David L. The Battle of the Monongahela and the Road to Revolution (2015)

- Russell, Peter. "Redcoats in the Wilderness: British Officers and Irregular Warfare in Europe and America, 1740 to 1760", The William and Mary Quarterly (1978) 35#4 pp. 629–652 in JSTOR

External links

[edit]Braddock Expedition

View on GrokipediaHistorical Context

Origins of the French and Indian War

The origins of the French and Indian War lay in competing imperial claims to the Ohio River Valley, a region rich in fur trade potential and strategic for linking French possessions from Canada to Louisiana. Both Great Britain and France asserted sovereignty over this territory following the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748, which ended King George's War without resolving border ambiguities. French authorities viewed British colonial expansion westward as a direct threat to their trade networks with Native American tribes, prompting expeditions to reassert control; in 1749, Pierre-Joseph Céloron de Blainville led a force to bury lead plates claiming the valley for France and to warn British traders to withdraw.[4] By 1753, France constructed a chain of forts including Presqu'ile, Le Boeuf, and Machault to secure the area and facilitate military presence.[5] British interests, driven by colonial land speculators and governors seeking to expand settlement and commerce, intensified the rivalry. The Ohio Company of Virginia, chartered in 1748 and granted 200,000 acres by King George II in 1749, aimed to establish trading posts and settlements in the valley, with Virginia Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie serving as a key proponent and treasurer.[6][7] In response to French fort-building, Dinwiddie dispatched Major George Washington in 1753 to deliver a demand for French withdrawal, which was rebuffed as the French cited prior explorations and alliances with indigenous groups like the Huron and Algonquin.[8] These actions reflected Britain's imperative to counter French encirclement of its Atlantic colonies, as the Ohio Valley offered vital access to western interior resources.[9] Tensions escalated into open conflict in 1754 when Washington, on a second mission with a small force and allied Mingo leader Tanacharison, ambushed a French detachment led by Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville at Jumonville Glen on May 28, resulting in Jumonville's death amid disputed circumstances of whether it was an assassination or legitimate combat against an encroaching party.[10][11] The French retaliated by besieging Washington's improvised Fort Necessity, forcing his surrender on July 3, 1754, under terms admitting responsibility for Jumonville's "assassination."[12] These skirmishes marked the war's ignition in North America, drawing in Native allies on both sides and prompting Britain to dispatch regular troops, while France reinforced its positions, transforming local frontier clashes into a broader imperial struggle.[13][9]British Strategic Imperatives Against French Expansion

French forces advanced into the Ohio River Valley starting in 1753, constructing forts from Lake Erie southward to assert control over the region and block British westward expansion, culminating in the establishment of Fort Duquesne at the strategic Forks of the Ohio (modern Pittsburgh) in mid-1754 after destroying a British outpost there on April 17.[14] This encroachment violated British charters granting Virginia territory to the "South Sea" and threatened colonial land speculations by groups like the Ohio Company, which held 200,000 acres in the area for settlement and fur trade.[15] British traders had increasingly competed with French commerce among Native American tribes since the 1740s, but French forts enabled raids that disrupted these routes and allied tribes against British interests.[16] Following Lieutenant Colonel George Washington's surrender at Fort Necessity on July 3, 1754, after earlier clashes including the Jumonville Glen skirmish, Virginia Governor Robert Dinwiddie appealed to London for military aid to expel the French.[14] The British cabinet, led by Prime Minister Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle, responded by authorizing a multi-pronged offensive in 1755 to reclaim North American territories, with Major General Edward Braddock tasked specifically to capture Fort Duquesne and dismantle the chain of French forts in the Ohio Valley.[1] This expedition, departing from Alexandria, Virginia, in April 1755 with approximately 2,400 troops, aimed to secure the frontier against French-inspired Native American attacks that had already killed or captured hundreds of British settlers and traders.[1] The imperatives extended beyond immediate defense to imperial rivalry: controlling the Ohio Valley would open trans-Appalachian trade and settlement, neutralize French influence over key tribes like the Delaware and Shawnee, and prevent France from dominating the continent's interior waterways linking to the Mississippi.[16] Braddock's instructions emphasized diplomatic overtures to Native groups, promising restoration of their lands from French encroachments to secure alliances or neutrality, reflecting Britain's recognition that military success required indigenous support in irregular frontier warfare.[16] Failure to act risked ceding the region entirely, as French reinforcements bolstered Fort Duquesne amid escalating tensions.[14]Planning and Forces

British Government Directives and Resources

In response to escalating French fortifications in the Ohio Valley following the 1754 defeat of British colonial forces at Fort Necessity, the British government appointed Colonel Edward Braddock to the rank of major general and commander-in-chief of all forces in North America on 24 September 1754, upon recommendation from the Duke of Cumberland, captain-general of the British Army.[17] His explicit directives, issued by the Secretary at War and aligned with the broader 1755 campaign strategy coordinated by the Duke of Cumberland, required him to assemble forces in Virginia, march westward from Wills Creek through Maryland and Pennsylvania to capture Fort Duquesne—the strategic French fort at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers—and subsequently proceed against forts such as Niagara, Crown Point, and Beauséjour, without discretionary deviation from these sequential objectives.[17][18] To execute these orders, the government committed two regular infantry regiments from the Irish establishment: the 44th Regiment of Foot under Colonel Sir Peter Halkett and the 48th Regiment of Foot under Colonel Thomas Dunbar, each with roughly 500-600 rank-and-file upon embarkation in early 1755, supplemented by detachments of grenadiers, light infantry, and seamen for engineering tasks.[19][17] These units, approved in a memorandum by the Duke of Cumberland on 16 November 1754, were transported from Cork, Ireland, arriving in Virginia by late February and March 1755, marking the first major deployment of British regulars to the American interior.[18] Artillery and technical support included a train of six 12-pounder cannons, four 6-pounder guns, two howitzers, and several mortars, manned by a company of the Royal Artillery under Captain Robert Orme and engineers led by Captain Robert Lewis, all shipped from Britain to ensure European-style siege capabilities against the wooden fort.[1] Initial funding totaled approximately £50,000 from the War Office, advanced in part via a £10,000 loan negotiated by Braddock with London merchant John Hanbury of Thomlinson & Hanbury, the crown's primary fiscal agents for North American military remittances; colonies were directed to reimburse through a centralized quota system, with contributions such as £6,000 each from Maryland and North Carolina, and £5,000 from New York, though enforcement relied on royal governors exerting pressure on reluctant assemblies.[17][20] Logistical directives emphasized colonial provisioning of wagons, horses, and draft animals—up to 459 wagons and 2,700 horses ultimately procured, largely through Virginia's efforts under Governor Robert Dinwiddie—while prohibiting trade with French territories and mandating coordination with provincial militias, though Braddock's instructions underscored reliance on regular discipline over irregular colonial tactics.[17][1] This resource allocation reflected Britain's shift toward direct imperial intervention, prioritizing professional forces to counter French and Native American alliances, but presupposed robust colonial subsidy that proved uneven due to intercolonial disputes and pacifist influences in assemblies like Pennsylvania's.[17]Composition and Strength of the Expedition

The Braddock Expedition assembled at Fort Cumberland in May 1755 with a total strength of approximately 2,400 men, comprising British regulars, colonial provincials, artillery specialists, and minimal Native American scouts. This force represented Britain's primary offensive thrust in the Ohio Country theater of the French and Indian War, emphasizing conventional European linear tactics adapted—imperfectly—to frontier conditions. Logistical support included a train of wagons, packhorses, and artillery pieces, though shortages in draft animals hampered mobility from the outset.[1][3] The infantry core consisted of two understrength British regiments reinforced by drafts from other units: the 44th Regiment of Foot, commanded by Colonel Sir Peter Halkett, and the 48th Regiment of Foot, under Colonel Thomas Dunbar, totaling around 1,400 rank-and-file soldiers organized into ten companies each. These regulars, shipped from Ireland and Gibraltar, formed the expedition's disciplined backbone but lacked experience in irregular woodland warfare. Provincial troops supplemented the force with roughly 600–700 men from Virginia (including ranger and carpenter companies for scouting and engineering), Maryland, North Carolina, New York, and South Carolina independent companies, providing local knowledge but varying in training and reliability.[21][22][3]| Component | Approximate Strength | Details |

|---|---|---|

| British Regular Infantry (44th & 48th Foot) | 1,400 men | 700 per regiment; ten companies each, focused on musket volleys and bayonet charges.[21][22] |

| Colonial Provincials | 600–700 men | Virginia rangers (~250), carpenters (~100), horse (~28); plus companies from MD (80), NC (84), NY, SC; tasked with scouting, labor, and augmentation.[21][22] |

| Artillery & Engineers | ~60–100 men | Royal Artillery detachment with 27 cannon (including 6 × 12-pounders, 6 × 6-pounders, 4 howitzers); no formal engineers, relying on provincial carpenters.[3][22] |

| Support (Sailors, Officers, etc.) | ~50–100 men | 30–35 Royal Navy sailors for gun handling; aides like George Washington; minimal Indian allies (fewer than 10).[21][1] |

Leadership Structure

General Edward Braddock's Background and Approach

Edward Braddock was born in January 1695 in Perthshire, Scotland, to a major general in the Coldstream Guards.[2] At age 15 in 1710, he received an ensign's commission in his father's regiment, beginning a 45-year military career marked by steady promotions through European service.[23] [1] By 1716, he had advanced to lieutenant, and he commanded troops during the Siege of Bergen op Zoom in 1747, earning recognition for valor.[2] Further promotions followed, to colonel in 1745 and major general in 1754, reflecting his adherence to conventional British army discipline honed in continental warfare.[24] In late 1754, following George Washington's defeat at Fort Necessity, Braddock was appointed commander-in-chief of British forces in North America and tasked with capturing French-held Fort Duquesne in the Ohio Valley as part of a coordinated 1755 offensive.[1] Arriving in Virginia in February 1755, he assembled approximately 2,400 troops, including two regular infantry regiments, colonial recruits, and a small contingent of Native American allies, at Fort Cumberland.[24] [1] His approach emphasized European linear tactics, with forces advancing in formal columns protected by wagons and heavy artillery, while engineering a widened road through the Allegheny Mountains for supply lines.[2] To accelerate the final push, Braddock divided his army into a "flying column" of about 1,300 lighter-equipped men, leaving the bulk to guard provisions, a decision predicated on intelligence suggesting the fort was weakly defended.[23] [2] Braddock's rigid adherence to regular army protocols clashed with frontier realities and colonial suggestions for adaptation, such as lighter transport and greater use of scouts or Native auxiliaries, which he largely dismissed in favor of disciplined formations vulnerable to ambush.[2] As aide-de-camp, Washington urged reconnaissance and irregular tactics suited to wooded terrain, but Braddock prioritized maintaining order among raw recruits unaccustomed to parade-ground precision amid wilderness hardships.[1] This conventional strategy, effective in open European fields but ill-suited to guerrilla warfare employed by French and Indian forces, underscored Braddock's underestimation of the expedition's logistical and tactical demands.[23]Colonial Officers and George Washington's Role

The Braddock Expedition augmented its British regular infantry with approximately 500 provincial troops, primarily rangers and scouts from Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina, organized into independent companies suited for frontier operations.[1] These colonial forces were commanded by provincial officers with prior experience in the Virginia Regiment or local militia, including Lieutenant Colonel Adam Stephen, who led elements of the Virginia contingent, and Captain Andrew Lewis, both of whom had participated in earlier Ohio Valley campaigns and emphasized irregular tactics adapted to wooded terrain.[21] Subordinate to British command, these officers focused on reconnaissance and supply protection, though tensions arose from Braddock's preference for conventional discipline over colonial methods, leading to underutilization of their expertise in ambush avoidance and Native alliances.[2] George Washington, then 23 years old and a former lieutenant colonel in the Virginia Regiment, volunteered as an unpaid aide-de-camp to Braddock to preserve his autonomy and avoid conflicts over rank precedence with regular army officers.[25] Appointed following correspondence with Braddock's secretary Robert Orme, Washington's role leveraged his familiarity with the region from the 1754 engagements at Jumonville Glen and Fort Necessity, where he had scouted French positions and endured surrender.[20] His duties included transcribing orders in the expedition's orderly book from February to June 1755, dispatching couriers with instructions—such as procuring funds and wagons—and advocating for flankers and scouts to counter guerrilla threats, advice rooted in observed French and Indian ambushes but frequently dismissed in favor of rigid column formations.[26] [27] Despite contracting dysentery during the advance, Washington continued active service, positioning him to assume ad hoc leadership after Braddock's wounding on July 9.[28]The March to Fort Duquesne

Engineering Braddock's Road

The construction of Braddock's Road commenced on May 30, 1755, with an advance party of approximately 100 pioneers under engineers such as Harry Gordon and Patrick Mackellar, tasked with clearing a path from Fort Cumberland, Maryland, toward Fort Duquesne.[29][18] This effort involved felling trees with axes along an existing Indian trail known as Nemacolin's Path, grading the soil to create a 12-foot-wide roadway suitable for wagons and artillery, and navigating six major Allegheny Mountain ridges.[30] The total distance spanned nearly 125 miles of dense forest, steep ascents, ravines, swamps, and unbridged streams, where fording or temporary causeways were necessary.[31][30] Pioneers and fatigue parties of soldiers, supplemented by 30 seamen from Commodore Keppel's fleet for hauling heavy equipment, employed rudimentary techniques including straight-line surveying where terrain permitted, with detours around impassable sections like the Narrows pass.[30][18] Cuts were excavated up to 10 feet deep in rocky areas, and progress averaged 2 to 3 miles per day initially, hampered by the destruction of wagons on slopes such as Wills Mountain and the need to repair tools amid limited supplies.[30] By late June, the main force had advanced to Little Meadows, about 20 miles from the start, after several days of intensive labor that revealed the limitations of European road-building methods in American wilderness.[30] Further engineering adaptations included reconnaissance for alternate routes and the use of packhorses for lighter loads ahead of wagons, though the road's incompleteness—reaching only to the Monongahela River crossing by July 9—underscored the expedition's logistical strain.[30][31] This military road represented an unprecedented feat for its era, facilitating artillery transport over rugged terrain but at the cost of slowed momentum and exposed vulnerabilities.[18]Logistical Challenges and Terrain Adaptation

The Braddock Expedition encountered profound logistical difficulties in conveying a conventional European army across the Appalachian wilderness, necessitating the construction of a 12-foot-wide wagon road spanning approximately 110 miles from Fort Cumberland, Maryland, to Fort Duquesne through dense forests, steep mountain ridges, swamps, creeks, and rivers.[16][32] The terrain proved exceptionally demanding, with initial progress limited to about 20 miles in the first 10 days as engineer pioneers cleared paths, felled trees, bridged waterways, and filled marshy depressions, all while hauling heavy artillery—including six 12-pounder cannons, four 6-pounders, two howitzers, and mortars—along with siege supplies and provisions for over 2,000 men.[32][22] Particular obstacles included near-perpendicular descents such as that of Big Savage Mountain, which demolished numerous supply wagons and exacerbated equipment losses.[16] The reliance on a narrow preexisting Indian trail, ill-suited for large-scale wagon transport, compounded delays, as did the absence of intermediate supply depots, forcing the column to carry all necessities forward without secure rearward lines.[32] Colonial support fell short, with Virginia unable to provide adequate wagons, draft animals, and provisions, leading to overburdened horses that frequently broke down or perished.[22] To address the glacial pace—often no more than 1-2 miles per day initially—Braddock implemented a partial adaptation by dividing the force around June 18, 1755, at Little Meadows, detaching a flying column of roughly 1,400 light infantry, artillery, and officers with reduced baggage, substituting packhorses for wagons to accelerate the advance toward the objective.[32][33] This maneuver, advised in part by George Washington, who served as a volunteer aide and advocated for frontier-adjusted methods, enabled the vanguard to cover the final 40 miles more swiftly but left the trailing 900-man rear guard and supply train exposed and underprotected.[16][34] Further strains arose from environmental factors, including summer heat, contaminated water sources, and the physical exhaustion of troops unaccustomed to such labors, resulting in widespread illness and diminished combat readiness. Inadequate reconnaissance, limited to just eight scouts, hindered anticipation of terrain hazards and enemy movements, underscoring a broader failure to integrate local knowledge into logistical planning.[32] While the road-building effort represented a engineering feat that later facilitated western expansion, Braddock's rigid adherence to linear supply doctrines ill-adapted to the irregular frontier environment ultimately undermined the expedition's sustainability.[16][32]

Battle of the Monongahela

Final Approach and French-Indian Forces

Following the division of the expedition into a flying column earlier in June to accelerate the advance, Major General Edward Braddock led approximately 1,400 British regulars, colonial provincials, and support personnel toward Fort Duquesne along the rudimentary road cut through the wilderness. By early July 1755, the column had reached a point roughly 10 miles from the fort. On the morning of July 9, to shorten the route and avoid a bend in the Monongahela River, the troops forded the river to the east bank, marched about two miles parallel to it, then recrossed to the west bank before resuming the westward advance in a long, compact linear formation typical of European battlefield tactics.[22] The vanguard, consisting of light infantry under Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Gage, screened the main body, which included artillery pieces, grenadiers, and the bulk of the infantry, with wagons and baggage in the rear; the march proceeded with drums beating and colors flying, reflecting confidence in the proximity to the objective and underestimation of immediate threats.[3] At Fort Duquesne, Captain Daniel Liénard de Beaujeu, the senior French officer, received intelligence of the British approach from Native American scouts and coureurs de bois operating in the vicinity. With limited time, Beaujeu hastily rallied available garrison elements and allied warriors, who had been gathered through diplomatic overtures and promises of plunder, and marched out around 9 a.m. to intercept the expedition before it could invest the fort.[3] The opposing force comprised roughly 200 to 300 French colonial regulars from the Troupes de la Marine, Canadian militia, and coureurs de bois, supplemented by a larger contingent of Native American allies totaling 300 to 600 warriors drawn primarily from the Delaware, Shawnee, Mingo, Ottawa, Miami, Huron, and other tribes who had aligned with the French against British expansion.[22] [3] Overall strength estimates for the combined French-Indian command varied between 600 and 900, reflecting uncertainties in warrior turnout and historical accounts, but emphasizing the irregular, mobile nature of the force suited to woodland ambush tactics rather than open-field engagement.[22] [3] Beaujeu personally led the column, adopting Native war paint to symbolize resolve and integration with his allies, positioning the warriors to exploit the dense forest cover along the British line of march.[3]Tactics Employed and Sequence of Events

On July 9, 1755, Braddock's flying column of approximately 1,400 British regulars, provincials, and artillery pieces advanced in a narrow, extended formation along the recently cleared road, with a vanguard under Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Gage, followed by light infantry, wagons, and the main body containing Braddock himself.[33] The British employed conventional European tactics suited to open-field engagements, marching in disciplined columns designed for mutual support and volley fire, but lacking advanced skirmishers or flankers to scout the dense woods, a precaution Braddock had previously used successfully against smaller ambushes but omitted here due to overconfidence in the enemy's weakness.[33] Artillery, limited to a few 6-pounder guns with grapeshot, was positioned centrally but proved ineffective against dispersed assailants.[33] The opposing force, numbering about 855 under Captain Daniel Liénard de Beaujeu—comprising 72 French regulars, 146 Canadian militiamen, and 637 Native American warriors—adopted irregular guerrilla tactics, concealing themselves in the underbrush on both flanks of the anticipated British path rather than a fixed river-crossing ambush, exploiting the terrain's ravines and trees for cover and mobility.[33] Warriors, primarily from tribes allied with the French such as the Ottawa and Ojibwa, spread in a loose, enveloping half-moon formation, withholding fire to draw the British into the kill zone while using war cries to disorient and target officers preferentially, a method honed in woodland warfare that contrasted sharply with the British preference for massed ranks.[33] Beaujeu, dressed in Native garb to blend in, led the initial rush to engage the vanguard directly.[3] The sequence commenced around 1:00 p.m., shortly after the column completed its second crossing of the Monongahela River at noon to bypass rugged terrain, when Gage's vanguard encountered the French line and fired a volley, killing Beaujeu almost immediately and prompting the Native warriors to unleash flanking fire from concealed positions.[33] British troops, confined to the road's confines, attempted to deploy into linear firing lines for disciplined volleys, but the suppressive fire from elevated woods—exploiting the column's vulnerability without room to maneuver—caused rapid disorder, with officers falling at disproportionate rates (26 of 48 provincial officers and 86 of 1,000 regulars becoming casualties).[33] Braddock, rallying personally by riding forward under heavy fire, reinforced the center with reserves and urged adherence to rank-and-file tactics, briefly stabilizing parts of the line with artillery blasts, yet the lack of adaptation to the ambush's irregular nature led to panic as provincials like those under Washington sought cover in ditches while regulars huddled or broke.[3][33] As casualties mounted—exacerbated by the attackers' reloading from behind trees and tomahawk charges into gaps—Braddock ordered a retreat around 2:00 p.m., but a bullet struck him in the lung and arm while mounting his horse, transferring effective command amid the rout to aides and Washington, who organized a rear guard.[33] The survivors fled chaotically back across the Monongahela, pursued by warriors who scalped the fallen and plundered wagons, inflicting 456 killed and 422 wounded on the British side against minimal French-Indian losses (estimated at 3-30 killed).[33] This tactical mismatch, rooted in the British insistence on open-order discipline against an enemy leveraging concealment and hit-and-run envelopment, precipitated the expedition's collapse.[3]Defeat and Retreat

Braddock's Wounding and Loss of Command

During the intense fighting of the Battle of the Monongahela on July 9, 1755, General Edward Braddock remained prominently exposed on horseback at the center of the British column, directing operations amid the French and Native American ambush.[35] He demonstrated tenacity as four or five horses were successively shot from under him, yet he persisted in combat until struck by musket fire.[2] A bullet eventually penetrated Braddock's right arm and pierced his lung, with additional wounds reported to his abdomen, rendering him incapable of continued leadership.[35] [2] Conscious but gravely injured, Braddock was carried from the field after approximately three hours of battle, which had commenced around 1:00 p.m., marking the effective collapse of organized British resistance.[1] With Braddock incapacitated, formal command devolved to subordinate officers, including Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Gage and others, though chaos ensued due to heavy officer casualties—26 killed and 36 wounded out of 96.[36] George Washington, serving as a volunteer aide-de-camp without official rank in the chain of command, assumed de facto responsibility for rallying the disorganized troops and initiating the retreat, pleading with Braddock to withdraw to higher ground before the general's wounding sealed the decision.[37] This transition highlighted the expedition's tactical disarray, as Braddock's European-style formations proved vulnerable to irregular warfare, contributing to the rout.[38]Rally and Withdrawal Under Washington

Following General Edward Braddock's mortal wounding by musket fire during the Battle of the Monongahela on July 9, 1755, George Washington, then a 23-year-old aide-de-camp and colonel in the Virginia Regiment, assumed de facto leadership of the shattered advance column amid widespread panic. With British casualties exceeding 900 out of roughly 1,459 engaged—comprising about 500 killed and 500 wounded—troops fled in disorder along the recently cut road, abandoning equipment and the wounded.[35] [36] Washington, having already lost two horses and sustained four bullet holes through his coat without injury, rallied approximately 200 men to form a rudimentary rear guard capable of covering the withdrawal, though insufficient for offensive action.[35] Washington prioritized evacuating Braddock, who had been struck in the arm and lung, arranging for him to be transported on an improvised litter fashioned from a horse's saddle while French and Native American forces looted the battlefield rather than mounting an immediate pursuit, likely due to their own 90 casualties and tactical restraint.[35] [36] Exhausted after over 12 hours on horseback amid the fray, Washington nonetheless rode several miles rearward to Colonel Thomas Dunbar's baggage train encampment, approximately 7 miles from the engagement site, to urge reinforcement and organize supplies for the survivors' retreat.[35] This effort halted the immediate rout, enabling the column to consolidate briefly before resuming the march back along Braddock's Road toward the main supply base. The withdrawal proceeded in stages under Washington's oversight until formal command devolved to Dunbar on July 11 upon reaching his position, where the combined force numbered several hundred able-bodied survivors alongside hundreds of wounded.[35] Braddock, delirious and declining, died on July 13 near the Great Savage Mountain; Washington supervised his burial in the middle of the road, with troops ordered to trample the grave to obscure it from potential desecration by pursuers.[35] To lighten the load and deter enemy tracking, excess wagons and stores were burned, facilitating a grueling 60-mile trek marked by desertions, supply shortages, and the challenges of transporting the wounded over rugged terrain without effective medical support.[39] The remnants arrived at Fort Cumberland between July 17 and 19, 1755, having evaded total destruction despite the expedition's collapse; Washington's decisive actions in rallying disciplined elements and coordinating the initial phases preserved a core force, though the retreat underscored the regulars' vulnerability to irregular tactics and poor adaptation to frontier conditions.[36] [39] In his July 18 letter to his brother, Washington attributed the survival of key personnel to providence amid "all human probability" against them, reflecting on the "scandalous" disorder that claimed most field officers.[40]Immediate Aftermath

Casualties and Battlefield Recovery

The British force suffered devastating losses at the Battle of the Monongahela on July 9, 1755, with approximately 977 casualties out of 1,459 engaged, including 63 of 89 officers killed or wounded.[35] This represented over two-thirds of the column, with 456 killed and 520 wounded among regulars and provincials combined.[22] In contrast, French and Native American forces incurred far lighter losses, estimated at fewer than 30 killed overall, with French reports citing 23 dead and 16 wounded across allied combatants.[22][41] Battlefield recovery proved chaotic and incomplete amid the rout. Survivors, numbering around 500 effectives, retreated approximately 10 miles eastward that afternoon under covering fire, prioritizing the evacuation of as many wounded as wagons and manpower allowed, though many succumbed en route from blood loss or exposure.[1] The dead, including most officers, were largely abandoned on the field, where Native warriors scalped and mutilated hundreds of bodies in accordance with frontier customs, exacerbating the psychological toll on British morale.[38] French forces under Captain Liénard de Beaujeu (killed early) and subsequent commander Daniel Liévault de Coulon de Villiers returned to the site on July 12 to survey and partially bury remains, motivated partly by sanitary concerns near Fort Duquesne.[3] Major General Edward Braddock, mortally wounded by multiple musket balls during the action, lingered until July 13 before succumbing near Great Meadows.[42] Washington, acting in an advisory capacity, supervised Braddock's burial in the middle of Braddock's Road to conceal the site from potential Native desecration; troops then marched wagons over the grave to erase traces, a tactic that succeeded until bones were rediscovered during road repairs in 1804 and reinterred with honors.[36][42] No systematic recovery of other British dead occurred immediately, leaving the battlefield a grim testament to the expedition's failure until later colonial efforts.[38]Frontier Repercussions and Indian Raids

The defeat at the Battle of the Monongahela on July 9, 1755, exposed the British colonial frontiers to immediate vulnerability, as the routed expedition withdrew eastward without securing the Ohio Country or providing defensive garrisons. French commanders at Fort Duquesne exploited this vacuum, encouraging allied Native American warriors—primarily Delaware, Shawnee, and Mingo—to disperse from the battlefield and initiate raids on unprotected settlements. These actions stemmed from the tribes' perception of British weakness, reinforced by the expedition's failure to dislodge French influence, which in turn strengthened Native alliances with New France through promises of trade goods, ammunition, and territorial autonomy.[1][31] Raids proliferated across Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Maryland in the ensuing months, targeting farms, villages, and supply lines with tactics emphasizing ambush and scalping to terrorize colonists. Warriors returned to Fort Duquesne laden with prisoners and scalps, further incentivizing participation; attacks extended deep into settled areas, reaching within 50 miles of Philadelphia by late 1755. In Pennsylvania alone, the frontier descended into widespread insecurity, with settlers abandoning outlying homes and congregating in makeshift defenses, as provincial authorities struggled to muster adequate rangers amid proprietary disputes. Virginia's backcountry faced similar incursions, prompting Colonel George Washington to organize local militias for patrols, though chronic shortages of men and supplies limited effectiveness.[22][43][3] The raids inflicted heavy tolls, with hundreds of colonists killed, wounded, or captured in 1755–1756, exacerbating economic disruption through livestock theft and crop destruction. Specific incidents, such as the October 16, 1755, assault on Penn's Creek in central Pennsylvania—where Delaware warriors under Shingas killed at least 26 settlers and abducted over 100—illustrated the scale of penetration and the inadequacy of scattered colonial responses. These operations not only avenged prior encroachments but also aimed to deter further British expansion, sustaining French strategic pressure without committing regular troops. Colonial governors, including Virginia's Robert Dinwiddie and Pennsylvania's Robert Hunter Morris, petitioned for imperial reinforcements, leading to the eventual construction of frontier fort chains, though initial delays amplified panic and depopulation.[22][44]Legacy and Assessments

Military Lessons on Conventional vs. Irregular Warfare

The Braddock Expedition exemplified the profound mismatch between conventional European warfare tactics and the irregular methods employed by French-allied Native American warriors in North American terrain. British regular infantry, trained for open-field battles with linear formations and massed volleys, advanced on July 9, 1755, in a tightly packed column along the Monongahela River, prioritizing supply wagons and artillery over dispersal.[33] This rigid structure, effective on European plains, proved catastrophic in dense woods, where approximately 300 French regulars and 600 Native warriors ambushed from concealed positions on elevated ground and ravines, delivering aimed fire from cover without exposing themselves to counterfire.[31] The attackers' mobility allowed them to shift flanks rapidly, exploiting the British inability to maneuver or deploy scouts effectively, resulting in over 900 British casualties from a force of about 1,400 while enemy losses numbered fewer than 30.[33][31] A critical tactical failing was Braddock's dismissal of skirmisher deployment and flank security, staples of European light infantry adapted for wooded environments, in favor of maintaining parade-ground discipline.[33] George Washington, advising as aide-de-camp, repeatedly urged the use of provincial rangers and Native scouts for reconnaissance and irregular screening, but Braddock rejected such "skulking" methods as unbecoming to redcoats.[16] Consequently, the column lacked early warning, collapsing into panic when fired upon from unseen positions, with soldiers breaking ranks to seek cover—a direct contrast to the attackers' disciplined, terrain-integrated guerrilla approach that maximized surprise and psychological terror through whoops and selective scalping.[31] This underscored the causal primacy of local adaptation: conventional firepower and drill yielded to irregular forces leveraging superior knowledge of the landscape for hit-and-run engagements.[45] The defeat prompted British military reevaluation, highlighting the need for hybrid forces blending regular discipline with irregular capabilities for frontier operations.[46] Post-1755, the British established ranger companies, such as those under Robert Rogers, trained in woodcraft, ambushes, and light infantry tactics to counter Native irregulars, marking a shift from Braddock's Eurocentric rigidity.[46][16] Washington later applied these lessons in forming his Virginia Regiment as a versatile unit for both conventional sieges and skirmishes, influencing American provincial militias' emphasis on mobility over formation.[16] Ultimately, the expedition demonstrated that in asymmetric colonial conflicts, empirical success favored forces prioritizing reconnaissance, dispersion, and environmental integration over numerical superiority or formal tactics alone.[45][46]Enduring Infrastructure: Braddock's Road and Later Campaigns

The Braddock Expedition constructed Braddock's Road, the first wagon-capable military route spanning approximately 140 miles from Fort Cumberland in Maryland across the Allegheny Mountains to the Monongahela River near Fort Duquesne.[1] Engineers under Major John St. Clair oversaw the effort, which involved felling trees, filling ravines, and bridging waterways to accommodate heavy artillery and supply wagons, completing the primary segment by early July 1755.[1] This infrastructure persisted beyond the expedition's failure, serving as a foundational artery for British and colonial military logistics in the Ohio Valley.[16] Although Brigadier General John Forbes elected in 1758 to forge a new, more northerly road from Raystown (modern Bedford, Pennsylvania) to avoid vulnerabilities exposed in Braddock's defeat, Colonel George Washington strongly advocated reusing and improving Braddock's established path for its directness and existing improvements.[47] [48] Washington's Virginia Regiment utilized repaired sections of the road during 1756–1758 frontier defense operations, including advances to support Forbes' campaign and the erection of outposts like Fort Loudoun at Winchester, Virginia.[16] The road's presence enabled sustained supply lines, contributing indirectly to Forbes' successful capture of Fort Duquesne in November 1758 and the subsequent founding of Fort Pitt.[38] Braddock's Road facilitated a strategic reorientation of warfare toward North America's interior, allowing British forces to project power beyond the Appalachian barrier.[16] In subsequent conflicts, such as Pontiac's War (1763–1766), elements of the route supported relief expeditions to Fort Pitt, including Colonel Henry Bouquet's 1764 campaign against Ohio Valley tribes.[38] During the American Revolutionary War, the road saw employment by Continental supply convoys and militia movements westward, underscoring its role in enabling trans-montane operations despite initial conventional tactics' shortcomings.[16] Over time, segments evolved into civilian thoroughfares, forming the basis for later infrastructure like the National Road, but its immediate military value lay in bridging eastern colonies to western frontiers.[49]Controversies in Blame Attribution and Tactical Realities

Historians have long attributed the Braddock Expedition's failure primarily to General Edward Braddock's insistence on conventional European linear tactics ill-suited to the North American frontier, where dense forests and ravines limited visibility and favored concealed irregular fire from French and Native American forces.[33] This view posits that Braddock's overconfidence led him to dismiss warnings, such as Benjamin Franklin's 1755 letter highlighting the vulnerability of a extended supply column to ambushes, and to underutilize colonial rangers for scouting despite their familiarity with woodland combat.[33] Consequently, on July 9, 1755, at the Battle of the Monongahela, Braddock's flying column of approximately 1,466 men advanced in tight formations along a narrow road, exposing them to enfilading fire that caused 878 casualties—456 killed and 422 wounded—while the opposing force of 855 (including 637 Native warriors) suffered only about 30 killed and 60 wounded.[33] Further blame has focused on Braddock's limited recruitment of Native allies, securing only eight scouts despite colonial offers, which deprived the expedition of essential intelligence and flanking capabilities against superior Native marksmanship and mobility.[33] Critics, including contemporaries like George Washington, noted that British regulars, unaccustomed to firing from cover, panicked under sustained volley from trees and underbrush, leading to friendly fire incidents and breakdown of discipline, as the troops' training emphasized massed volleys in open fields rather than dispersed skirmishing.[16] This tactical mismatch, compounded by the battle's evolution from a meeting engagement—rather than a premeditated ambush—into chaos over three hours, underscored the causal reality that European drill formations collapsed when unable to return coordinated fire against hidden attackers exploiting terrain advantages.[33] Recent scholarship, notably David L. Preston's analysis drawing on French, Native, and British archives, challenges the overemphasis on Braddock's personal failings by highlighting his logistical successes, such as constructing a 12-foot-wide wagon road across the Appalachians in weeks, and crediting the defeat to the tactical proficiency of French Captain Daniel Liénard de Beaujeu and Native warriors who enveloped flanks with disciplined fire.[16] Preston argues that Braddock employed vanguard flankers and scouts per standard practice, but these were outnumbered and outmaneuvered by a force leveraging superior knowledge of the landscape and rapid deployment, shifting attribution from British arrogance to the underappreciated agency and skill of adversaries who inflicted two-thirds casualties on Braddock's command.[38] Broader contingencies, including understrength regiments due to illness and poor inter-colonial coordination, further diluted blame on Braddock alone, revealing systemic British unpreparedness for frontier warfare rather than isolated command errors.[38] These debates persist, with empirical evidence from battle plans and survivor accounts affirming that while tactical adaptation was feasible, the decisive factors were the asymmetry in scouting efficacy and psychological resilience under irregular assault.[16]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Historic_Highways_of_America/Volume_4/Chapter_4