Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pakistan Rangers

View on Wikipedia

| Pakistan Rangers پاکستان رینجرز | |

|---|---|

| Common name | Rangers |

| Abbreviation | PR |

| Motto | Ever ready[1] |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | 1942 (as Sindh Rifles) |

| Employees | 40,730[2] |

| Annual budget | Rs. 25.95 billion (2020)[3] |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Federal agency (Operations jurisdiction) | Pakistan |

| Operations jurisdiction | Punjab Rangers in Punjab and Sindh Rangers in Sindh, Pakistan |

| Size | 317,164 km² (134,041 sq mi) |

| Population | 185,748,932 |

| Legal jurisdiction | Sindh Punjab Islamabad Capital Territory |

| Governing body | Ministry of Interior |

| Constituting instrument |

|

| General nature | |

| Specialist jurisdictions |

|

| Operational structure | |

| Headquarters |

|

| Agency executives |

|

| Parent agency | Civil Armed Forces |

| Website | |

| pakistanrangerssindh pakistanrangers | |

The Pakistan Rangers (Urdu: پاکستان رینجرز) are a pair of paramilitary federal law enforcement corps' in Pakistan. The two corps are the Punjab Rangers (operating in Punjab province with headquarters in Lahore) and the Sindh Rangers (operating in Sindh province with headquarters in Karachi). There is a third corps headquarters in Islamabad but it is only for units transferred from the other corps for duties in the federal capital. They are both part of the Civil Armed Forces.

The corps' operate administratively under the Pakistan Army but under separate command structures and wear distinctly different uniforms. However, they are usually commanded by officers on secondment from the Pakistan Army. Their primary purpose is to secure and defend the approximately 2,200 km (1,400 mi) long mutually recognised India–Pakistan border. This border does not include the heavily militarized Line of Control (LoC) in the Kashmir conflict, where the Pakistani province of Punjab adjoins Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir. Consequently, the LoC is not managed by the paramilitary Punjab Rangers, but by the Pakistan Army. They are also often involved in major internal and external security operations with the regular Pakistani military and provide assistance to provincial police forces to maintain law and order against crime, terrorism and unrest. In addition, the Punjab Rangers, together with the Indian Border Security Force, participate in an elaborate flag lowering ceremony at the Wagah−Attari border crossing east of Lahore.

As part of the paramilitary Civil Armed Forces, the Rangers can be transferred to full operational control of the Pakistan Army in wartime and whenever Article 245 of the Constitution of Pakistan is invoked to provide "military aid to civil power". An example of this is the Sindh Rangers deployment in Karachi to tackle rising crime and terrorism. Although these deployments are officially temporary because the provincial and federal governments have to allocate policing powers to the corps, they have in effect become permanent because of repeated renewal of those powers.

In July 2025, a tragic incident in Karachi's SITE-A Area drew attention to the deteriorating morale and working conditions within the Pakistan Rangers. A clash between a Rangers personnel and a police officer escalated into a deadly shootout, resulting in the death of Police Constable Waseem Akhtar and serious injuries to a Rangers official, Nauman, who was deployed with the 34 Wing. Nauman, reportedly under extreme stress, remains unconscious in hospital care.

Observers and law enforcement sources noted that the altercation reflected deeper systemic issues, including poor mental health support, low wages, and inadequate living conditions faced by paramilitary personnel. The incident reignited public debate over the lack of institutional reforms and the psychological toll on frontline forces operating in high-pressure urban deployment.[5]

History

[edit]

The origins of the Pakistan Rangers go back to 1942, when the British government established a special unit in Sindh known as the Sindh Police Rifles (SPR) which was commanded by British Indian Army officers. The force was established to fight the rebellious groups in sindh as the British government was engaged in World War II. Headquarters of this force was established in Miani Lines Pacca Barrack, Hyderabad Cantonment.

After the independence of Pakistan in 1947, the name of the force was changed from "Sindh Police Rifles" to "Sindh Police Rangers" and the protection of eastern boundaries with India was allotted to various temporary forces, such as the Punjab Border Police Force, Bahawalpur State Police, Khairpur State Police and Sindh Police Rangers.

Because the Rangers were neither correctly structured nor outfitted for a specific duty, on 7 October 1958 they were restructured and renamed to the West Pakistan Rangers.[4] In 1972, following the independence of East Pakistan and Legal Framework Order No. 1970 by the Government of Pakistan, the force was officially renamed from the West Pakistan Rangers to the Pakistan Rangers and put under control of the Ministry of Defence with its headquarters at Lahore.

In 1974, the organization became part of the Civil Armed Forces under the Pakistani Ministry of Interior, where it has remained since.

In late 1989, due to growing riots and the worsening situation of law and order in the province of Sindh, a new force was raised for a strategic anti-dacoit operation. The paramilitary force operated under the name of the Mehran Force and consisted of the then-existing Sindh Rangers, three battalions of the Pakistan Army (including the Northern Scouts). The Mehran Force was under the direct command of the Director-General (DG) of the Pakistan Rangers with its nucleus headquarters at the Jinnah Courts in Karachi.

Following these series of events, the federal government decided to substantially increase the strength of the Pakistan Rangers and raise a separate, dedicated headquarters for them in the province of Sindh. On 1 July 1995 the Pakistan Rangers were bifurcated into two distinct forces, the Pakistan Rangers – Punjab (Punjab Rangers) and Pakistan Rangers – Sindh (Sindh Rangers). Consequently, the Mehran Force and other Pakistani paramilitary units operating in the province of Sindh were merged with and began to operate under the Sindh Rangers.[6]

Wartime responsibilities

[edit]

The West Pakistan Rangers fought alongside the Pakistan Army in several conflicts, namely the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 and the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971.[7] After the war in 1971 and subsequent independence of Bangladesh, the force was federalized under the Ministry of Defence as the Pakistan Rangers and shortly afterwards in 1974, it was made a component of the Civil Armed Forces (CAF) under the Ministry of Interior. Since then, the Pakistan Rangers are primarily responsible for guarding the border with neighbouring India during times of peace and war.

The Pakistan Rangers have participated in military exercises with the Pakistan Army's Special Service Group (SSG) and also assisted with military operations in the past since their revitalization and rebuilding after the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. The first such participation was in 1973, when they operated under the command of the SSG to raid the Iraqi embassy in Islamabad alongside local police. In 1992, the Sindh Rangers saw an extensive deployment throughout Karachi to keep peace in the city in support of the Government of Sindh. The Sindh Provincial Police and Pakistan Rangers were involved in Operation Blue Fox against the MQM with direction from the Pakistan Army. Due to their close association with the military, the Rangers also saw combat against regular Indian troops during the Kargil War of 1999 in Kashmir. In 2007, the Pakistan Rangers alongside regular Pakistani soldiers and SSG commandos participated in Operation Silence against Taliban forces in Islamabad. The conflict started when, after 18 months of tensions between government authorities and Islamist militants, Taliban militants attacked the Punjab Rangers guarding the nearby Ministry of Environment building and set it ablaze. Immediately following this event, they proceeded to attack a nearby Pakistani healthcare centre, kidnapping an abundance of Chinese nurses, and subsequently locked themselves inside the Red Mosque with hostages.[8] Two years later, in 2009, the Rangers once again participated in a special military operation in Lahore alongside the SSG, when twelve terrorists operating for the Taliban attacked the Manawan Police Academy in Lahore. The operation ended with eight militants killed and four captured.[9] Later that year, the Government of Pakistan deployed the Punjab Rangers to secure the outskirts of Islamabad when the Taliban had taken over the Buner, Lower Dir, Swat and Shangla districts. Following these incidents, the Rangers participated in the Pakistan Army's Operation Black Thunderstorm.[10]

Role

[edit]

Aside from the primary objective of guarding the border with India, the Rangers are also responsible for maintaining internal security in Pakistan and serve as a major law enforcement organization in the country. Despite this, they do not possess the power to make arrests like the regular police with the exception of when the state temporarily sanctions them with such an authority in times of extreme crisis. Their primary objective as an internal security force is to prevent and suppress crime by taking preventive security measures, cracking down on criminals and thwarting organized crime with the use of major force. All suspects apprehended by the Rangers during a crackdown are later handed over to police for further investigation and possible prosecution when the chaos is brought under control. The same privileges are also temporarily granted by the government to other security organizations such as the Frontier Corps for the same reasons.

The Rangers are also tasked with securing important monuments and guarding national assets in all major cities, including Islamabad.

In the past, they have also served as prison guards for high-profile terrorists until they were withdrawn from such duties.[11]

The Rangers have notably contributed towards maintaining law and order in Islamabad, Karachi and Lahore in major crises. Due to the developing internal instability in Pakistan, the Rangers have become an extremely necessary force to maintain order throughout the provinces of Sindh and Punjab.

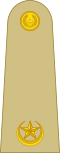

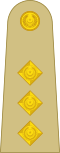

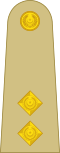

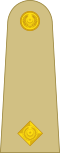

Ranks

[edit]| Rank group | General / flag officers | Senior officers | Junior officers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistan Rangers |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Director general ڈائریکٹر جنرل |

Senior superintendent of the Rangers سینئر سپرنٹنڈنٹ۔ |

Superintendent of the Rangers سپرنٹنڈنٹ |

Deputy superintendent of the Rangers ڈپٹی سپرنٹنڈنٹ۔ |

Inspector انسپکٹر |

Direct Entry Sub inspector ڈائریکٹ انٹری سب انسپکٹر۔ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank group | Junior commissioned officers | Non commissioned officer | Enlisted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistan Rangers |

|

|

|

No insignia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Senior inspector سینئر انسپکٹر۔ |

Inspector انسپکٹر |

Sub inspector سب انسپکٹر۔ |

Havildar حوالدار۔ |

Naik نائیک۔ |

Lance Naik لانس نائیک۔ |

Sepoy سپاہی۔ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gallery

[edit]-

Pakistani Rangers guarding the Tomb of Muhammad Iqbal in Iqbal Park, Lahore

-

Baba Chamliyal Mela at the Indo-Pakistani International Border, near Jammu.

-

Indian BSF personnel and Pakistani Rangers during the Wagah-Attari border ceremony.

-

A Pakistani Ranger in ceremonial dress.

-

A Pakistani Ranger standing by in ceremonial dress.

-

A Pakistani Ranger during the Wagah-Attari border ceremony.

-

Pakistani Rangers at the Wagah-Attari border crossing.

-

Punjab Rangers near the Indo-Pakistani border with G3 battle rifles.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Sandhu, Ijaz (6 September 2021). "Valiant Punjab Rangers in 65 War". The Nation. Archived from the original on 29 December 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ Waseem, Zoha (2022). "5: The other brother. A contested policing partnership.". Insecure Guardians: Enforcement, Encounters and Everyday Policing in Postcolonial Karachi. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-768873-1. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ "Federal Budget 2020–2021: Details of demands for grants and appropriations" (PDF). National Assembly of Pakistan. p. 2531. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ a b Pakistan Rangers Ordinance, 1959. Punjab Laws Online (Ordinance XIV). 1959. Archived from the original on 15 July 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ "Cop killed, Rangers man hurt in Karachi gunfight over 'personal dispute'". www.geo.tv. Retrieved 12 July 2025.

- ^ Pejek, Igor. Ljubic, Jovana (ed.). "Pakistan Rangers" (PDF). Strelok Analysis. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2017.

- ^ "Pakistan Army Rangers (Punjab)". Pakistan Army. Inter Services Public Relations. 2009. Archived from the original on 24 August 2010.

- ^ "102 killed in Lal Masjid operation, Sherpao". Geo TV. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ "How Pakistan academy attack started". BBC News. 30 March 2009.

- ^ Roggio, Bill (24 April 2009). "Rangers deployed to secure Islamabad outskirts". The Long War Journal. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ Asghar, Mohammad (17 December 2015). "Punjab withdraws Rangers from guard duties". Dawn.

External links

[edit]| External video | |

|---|---|

Pakistan Rangers

View on GrokipediaHistory

Formation and Early Development

The precursors to the Pakistan Rangers originated in British colonial border security units designed to patrol frontier regions vulnerable to smuggling, tribal incursions, and wartime threats. In 1942, amid World War II, the British administration formed the Sindh Police Rifles as a specialized paramilitary detachment in Sindh province to safeguard the southwestern border against potential Axis incursions and local unrest.[9] After Pakistan's partition from India in 1947, the inherited colonial forces underwent reorganization to address the security imperatives of the newly independent state's elongated and contested border with India. The Sindh Police Rifles were redesignated as the Sindh Rangers in 1949, expanding their mandate to include anti-smuggling operations and prevention of cross-border infiltration along the arid and riverine terrains.[10] In Punjab, analogous units such as the Sutlej Rangers emerged to secure the fluid, water-divided boundaries along rivers like the Sutlej, incorporating elements of pre-partition border police to counter immediate post-partition refugee movements and territorial disputes. These provincial formations operated semi-autonomously, relying on local recruitment and limited federal oversight, but faced challenges from resource shortages and the lack of unified doctrine. The push for centralization intensified in the mid-1950s as West Pakistan's government sought to streamline border defense amid rising Indo-Pakistani tensions. This led to the merger of provincial ranger units into the West Pakistan Rangers in 1958, laying the groundwork for a standardized force. The process culminated in the Pakistan Rangers Ordinance of 1959, which legally established the Pakistan Rangers as a federal paramilitary entity responsible for border patrolling, order maintenance, and rapid response to trans-border threats, effectively replacing fragmented provincial border police with a cohesive structure under interior ministry control. [11] Initial deployments emphasized fortification of vulnerable sectors, training in counter-infiltration tactics, and coordination with the Pakistan Army, marking the transition from ad hoc colonial legacies to a professionalized national asset.Post-Independence Expansion and Reforms

Following the partition of British India and Pakistan's independence on August 14, 1947, the paramilitary units responsible for border security, inherited from colonial structures, underwent immediate adaptation to serve the new state's defense needs along its eastern frontiers with India. The Sindh Police Rangers, established in 1942 as the Sindh Police Rifles to counter dacoity and border threats, were renamed Sindh Police Rangers and assigned primary responsibility for patrolling Sindh's borders, with an emphasis on preventing smuggling, infiltration, and maintaining order in vulnerable riverine and coastal areas. Similarly, in Punjab, legacy forces such as the Punjab Border Police and scouts units like the Sutlej Rangers were repurposed for frontier defense, drawing on their pre-partition roles in securing the Punjab's canal colonies and desert fringes against tribal incursions. These provincial forces faced challenges including manpower shortages, outdated equipment, and fragmented command structures amid the 1948 Indo-Pakistani War and subsequent border skirmishes, prompting calls for consolidation to enhance coordination and response capabilities. Under the martial law regime imposed by General Muhammad Ayub Khan on October 7, 1958, the disparate ranger elements were restructured into a unified West Pakistan Rangers, integrating units from Punjab and Sindh to form a more centralized paramilitary body equipped for systematic border surveillance and rapid deployment. This reform addressed operational inefficiencies by standardizing training, logistics, and intelligence-sharing, while expanding recruitment to bolster personnel strength for covering the extensive Indo-Pakistani border. The reorganization received statutory backing through the Pakistan Rangers Ordinance of 1959 (Ordinance No. XIV), which formally constituted the force under federal oversight, granting it powers to maintain security, patrol borders, and assist civil authorities in preserving order within designated areas.[3] The ordinance emphasized the Rangers' role in protecting national integrity against external threats, reflecting a strategic shift toward a professionalized, federally controlled entity capable of supporting the regular army without full militarization. Subsequent administrative tweaks in the early 1960s further refined command hierarchies, incorporating seconded army officers for leadership to improve discipline and tactical proficiency.Wartime and Post-9/11 Evolution

During the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, the Punjab Rangers served as the primary force confronting initial Indian incursions along multiple border sectors, including the Lahore front, where they absorbed heavy artillery barrages and infantry assaults before regular army reinforcements arrived.[12] Units such as those under Major Ilam defended key positions amid intense shelling, marking the Rangers' transition from routine border patrolling to active combat support alongside the Pakistan Army.[13] In the Rann of Kutch theater, Indus Rangers posts at locations like Mara and Kanjarkot repelled probing Indian patrols, highlighting their role in early warning and localized defense operations.[14] In the 1971 Indo-Pakistani War, Rangers contingents augmented regular forces on the western front, participating in defensive actions against Indian advances while maintaining border integrity amid divided national commitments.[15] Their involvement underscored a pattern of integration with military operations during existential threats, though deployments were constrained by the conflict's focus on the eastern theater and logistical dilutions with other paramilitary elements.[16] Post-September 11, 2001, the Rangers' mandate evolved amid Pakistan's confrontation with resurgent domestic militancy, particularly as spillover from Afghanistan intensified internal threats from groups like Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). Sindh Rangers, previously focused on border and urban policing, expanded into sustained counter-terrorism efforts, with approximately 7,000 personnel deployed in Karachi by 2011 to combat target killings, extortion, and extremist networks.[17] This shift culminated in the 2013 launch of targeted operations under the paramilitary's command, which dismantled criminal-terror syndicates, recovered arms caches, and reduced Karachi's violence ranking from among the world's most dangerous cities, enabling normalized civilian activity.[18][19] Punjab Rangers, meanwhile, retained primacy in eastern border security but contributed to national counter-militancy through intelligence-sharing and rapid response frameworks, reflecting a broader adaptation to hybrid threats prioritizing internal stability over purely external defense.[20]Organization and Structure

Command Hierarchy and Leadership

The Pakistan Rangers maintain a paramilitary command structure closely integrated with the Pakistan Army, with senior leadership drawn from army officers on deputation to ensure operational alignment and military discipline. Administratively, the force falls under the Ministry of the Interior, but command authority is exercised by Director-Generals (DGs) appointed by the Pakistan Army, typically requiring clearance from the Chief of Army Staff.[21][22] The Rangers are divided into two autonomous branches—Punjab Rangers and Sindh Rangers—each headed by a separate DG holding the rank of Major General, who oversees all strategic, tactical, and administrative decisions within their jurisdiction.[23][22] Beneath the DG, the hierarchy consists of sector headquarters, each commanded by a Brigadier or equivalent senior officer responsible for regional operations along borders or in urban areas. Sectors are further subdivided into wings—typically four per sector—led by Lieutenant Colonels or Majors, which manage companies of 100-150 personnel for patrolling, rapid response, and security enforcement. This tiered structure facilitates decentralized execution while maintaining centralized policy direction from the DG's headquarters, with Punjab Rangers based in Lahore and Sindh Rangers in Karachi.[9][22] Officer appointments emphasize army secondment, with ranks mirroring Pakistan Army equivalents up to Colonel, fostering interoperability during joint operations; enlisted personnel, however, are recruited directly into Rangers-specific roles with parallel non-commissioned structures. Leadership rotations occur periodically, often every two years, to prevent entrenchment and align with army career progressions, as evidenced by recent transitions such as the November 2024 appointment of Major General Muhammad Shamraiz as DG Sindh Rangers.[24][23] This model underscores the Rangers' dual civilian-military character, prioritizing border defense and internal stability under army-influenced command despite formal interior ministry oversight.[21]Punjab Rangers Command

The Punjab Rangers Command, headquartered in Lahore, serves as the operational headquarters for the Pakistan Rangers' activities in Punjab province. It is responsible for securing the province's eastern international border with India, which spans critical sectors including the Wagah-Attari crossing. The command operates under the Ministry of Interior and coordinates with the Pakistan Army for defense-related tasks.[25] Leadership of the Punjab Rangers Command is vested in the Director General, a Major General seconded from the Pakistan Army. Major General Muhammad Atif bin Akram assumed the role on 25 November 2023 and continues to lead as of early 2025, overseeing strategic operations, personnel deployment, and inter-agency coordination. The Director General reports to the federal government and manages a force engaged in both routine patrols and high-profile ceremonial duties.[26][27] The command's structure includes regional wings and battalions deployed across border sectors and urban centers in Punjab, such as Lahore, where Rangers provide internal security and guard key sites like the Tomb of Allama Iqbal. Responsibilities encompass border vigilance to counter infiltration and smuggling, assistance to civil authorities in maintaining law and order, and participation in national events like the Wagah border ceremony, which symbolizes military discipline and bilateral protocol. Personnel, numbering in the tens of thousands for the Rangers overall with a significant portion under Punjab Command, undergo specialized training for paramilitary roles.[28][29]Sindh Rangers Command

The Sindh Rangers Command, formally known as Pakistan Rangers (Sindh), operates as the provincial wing of the Pakistan Rangers paramilitary force, tasked with maintaining internal security, border patrol, and counter-terrorism duties primarily within Sindh province. Established through the bifurcation of the unified Pakistan Rangers on July 1, 1995, it absorbed pre-existing units such as the Mehran Force to address localized security needs in Sindh, evolving from the original Sindh Police Rifles formed in 1942 under British colonial administration.[9][30] The command's headquarters are located at the Jinnah Courts Building on Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road in Karachi, opposite the Pearl Continental Hotel, serving as the central hub for operations across the province.[31][32] Leadership of the Sindh Rangers Command is vested in a Director-General (DG) holding the rank of Major General, typically seconded from the Pakistan Army, ensuring alignment with federal military oversight. As of November 2024, Major General Muhammad Shamraiz assumed the role following a change-of-command ceremony, succeeding Major General Azhar Waqas who had served since 2022; the DG reports to the Ministry of Interior and coordinates with provincial authorities under constitutional provisions like Article 147 for law enforcement assistance.[33][34][35] The command's structure includes multiple wings and sectors, with a focus on rapid-response units for urban hotspots, though exact personnel figures remain classified; deployments emphasize Karachi, where significant forces are concentrated to combat organized crime and militancy.[23] In terms of operational mandate, the Sindh Rangers prioritize suppressing terrorism, extortion rackets, and ethnic-political violence in Sindh's urban centers, particularly Karachi, which has historically faced high levels of target killings and gang warfare. A pivotal effort was the Karachi Operation launched on September 5, 2013, following federal directives amid escalating violence, involving joint raids with police to dismantle militant hideouts, arrest operatives from groups like Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan affiliates, and seize illegal weapons; this initiative extended to other Sindh districts by July 2016, yielding a reported decline in violent incidents and improved city safety rankings.[18][36][37] The command also maintains vigilance along Sindh's border with India, conducting patrols and anti-smuggling operations, while specialized units like the Anti-Terrorism Wing handle high-risk interventions in Karachi's volatile neighborhoods.[38] Provincial governments have periodically extended the Rangers' special powers under the Anti-Terrorism Act, enabling direct action against criminals without prior police involvement, as renewed in 2018 and beyond to sustain gains against resurgence threats.[39]Ranks, Insignia, and Personnel Composition

The Pakistan Rangers employ a hierarchical rank structure influenced by the Pakistan Army for senior leadership, with paramilitary-specific designations for mid- and lower-level positions. The Director General of each command—Punjab and Sindh—is appointed from the Pakistan Army and holds the rank of Major General, overseeing operations through seconded senior officers such as Additional Directors General (typically Brigadiers).[24] Mid-level ranks include Superintendent of Rangers, Deputy Superintendent, and Chief Inspector, while junior commissioned ranks feature Senior Inspector, Inspector, and Sub Inspector, often filled via direct entry or promotion from enlisted personnel.[24] Enlisted ranks mirror Pakistan Army non-commissioned officers, comprising Havildar (Sergeant equivalent), Naik (Corporal), Lance Naik, and Ranger (Sepoy or private), with promotions based on service, training, and performance evaluations tied to Basic Pay Scale (BPS) grades ranging from BPS-5 for recruits to BPS-17 for Sub Inspectors.[40] Insignia for senior officers align with Pakistan Army patterns, using stars, crossed swords, and wreaths on shoulder epaulettes, but junior and enlisted ranks incorporate distinct Rangers badges, such as a crescent moon and star emblem on dark green or maroon backgrounds for shoulder slides and arm patches.[24] These designs emphasize paramilitary identity while maintaining interoperability with army units during joint operations. Personnel composition totals approximately 44,000 as of 2014, with Punjab Rangers numbering 19,865 and Sindh Rangers 24,247, primarily enlisted ranks supplemented by army deputation for command roles; recent recruitment drives include limited positions for female Rangers in general duty and clerical capacities.[2][41] The force draws recruits from provincial quotas, prioritizing physical fitness and loyalty, with training emphasizing border patrol and urban security over conventional warfare.| Rank Category | Key Ranks | BPS Grade (Approximate) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Senior Officers (Deputed) | Director General (Major General), Additional DG (Brigadier) | BPS-22+ | From Pakistan Army; oversee commands.[24] |

| Mid/Junior Officers | Superintendent, Deputy Superintendent, Senior Inspector, Inspector, Sub Inspector | BPS-17 to BPS-14 | Direct entry or promotion; handle field operations.[40] |

| Enlisted/NCO | Havildar, Naik, Lance Naik, Ranger | BPS-8 to BPS-5 | Core personnel for patrols and security duties.[40] |

Roles and Responsibilities

Border Security and Defense

The Pakistan Rangers, particularly the Punjab Rangers Command, serve as the primary paramilitary force responsible for securing Pakistan's eastern border with India, which extends over approximately 2,000 kilometers from the Rann of Kutch to the international boundary in Jammu. Established under the Pakistan Rangers Ordinance of 1959, their core functions include protecting persons and property in border areas, preventing smuggling of arms, ammunition, and other contraband, and countering illegal crossings and infiltrations by hostile elements.[29][4] These duties involve routine patrolling of border posts, deployment of checkpoints, and rapid response to incursions, acting as the first line of defense against potential invasions or terrorist activities originating from across the border.[21] In peacetime, the Rangers maintain vigilance through foot and vehicle patrols, often equipped with small arms like G3 rifles, and collaborate with the Pakistan Army for reinforced security in sensitive sectors. A prominent aspect of their border duties is participation in the daily flag-lowering ceremony at the Wagah-Attari crossing near Lahore, where Punjab Rangers personnel perform synchronized drills opposite India's [Border Security Force](/page/Border Security Force), symbolizing mutual military discipline while deterring unauthorized movements. This ritual, conducted since 1959, underscores their role in ceremonial deterrence and public displays of resolve.[42] During heightened tensions, such as ceasefire violations, Rangers have engaged in retaliatory firing along the Line of Control and international border, as reported in multiple incidents involving cross-border exchanges.[43] Historically, the Rangers have contributed to defense during major conflicts, including the 1965 and 1971 Indo-Pakistani Wars, where units reinforced army positions and repelled advances in key sectors like Lahore, demonstrating their integration into broader military operations while retaining paramilitary status. Their effectiveness in border defense relies on a personnel strength of around 50,000 for the Punjab command, trained in anti-infiltration tactics and supported by intelligence from national agencies. Despite expansions into internal security, border guarding remains their foundational mandate, with ongoing adaptations to threats like drone incursions and narcotics trafficking.[21][44]Internal Law Enforcement and Urban Security

The Pakistan Rangers, particularly the Sindh Rangers, conduct internal law enforcement operations in urban centers such as Karachi, supplementing provincial police in addressing organized crime, ethnic violence, and low-level terrorism. These efforts involve joint patrols, intelligence-led arrests, and targeted interventions against gangs, extortion rackets, and militant cells operating within city limits.[45][46] In response to escalating urban unrest, the federal government deployed Sindh Rangers for a major operation in Karachi on September 6, 2013, granting them enhanced powers under Section 5 of the Anti-Terrorism Act, 1997, to perform police functions including warrantless arrests, searches, and preventive detentions for up to 90 days. This operation, extended multiple times, resulted in the neutralization of over 1,000 criminals and militants by 2017, significantly reducing homicide rates from 2,367 in 2013 to 483 in 2016.[47][2] Powers under this framework were renewed periodically, including a 90-day extension on April 5, 2019, allowing continued urban policing amid persistent threats from groups like the Muttahida Qaumi Movement's armed factions and Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan affiliates. In Punjab, Rangers support urban security by deploying for crisis response in Lahore and guarding key infrastructure during high-risk events, though their role remains secondary to border duties.[48] As of October 12, 2025, Rangers and Sindh police formalized strategies for intensified joint operations targeting extortion, targeted killings, illegal arms displays, and terrorism, incorporating enhanced checkpoints and intelligence sharing to bolster urban stability. These activities align with Pakistan's National Internal Security Policy, emphasizing paramilitary-police coordination to counter urban militancy without supplanting civilian law enforcement.[49][2]Counter-Terrorism and Militancy Suppression

The Pakistan Rangers, as a paramilitary force, contribute to counter-terrorism by conducting intelligence-led operations, securing urban hotspots vulnerable to militant infiltration, and supporting law enforcement against terrorist financing and logistics networks. In Sindh province, particularly Karachi, Rangers units have targeted urban militancy linked to groups such as Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) affiliates and sectarian outfits, focusing on disrupting extortion rackets that fund insurgent activities.[45] Their mandate includes rapid response to terrorist threats, with personnel authorized under the Anti-Terrorism Act 1997 to exercise arrest, search, and seizure powers to preempt attacks. Amendments to the Anti-Terrorism Act in 2014 expanded Rangers' detention authority, allowing holds of up to 90 days for terrorism suspects without judicial oversight, enabling sustained pressure on militant cells embedded in criminal syndicates. This has facilitated operations against hybrid threats where militancy intersects with organized crime, such as target killings and bombings in densely populated areas. In Punjab, Rangers maintain specialized training facilities, including assault courses and urban combat simulations, to prepare for anti-terrorist scenarios, though their primary focus remains border security with secondary support for provincial counter-militancy efforts.[50] Rangers' involvement extends to joint actions with police and intelligence agencies under Pakistan's National Internal Security Policy, which coordinates paramilitary assets for intelligence sharing and operational integration against domestic extremism. Deployments have included reinforcement following high-profile attacks, such as clearing militant remnants from airports and public spaces, emphasizing their role in post-incident stabilization to prevent resurgence. These efforts prioritize empirical threat assessment over political considerations, though operational efficacy depends on inter-agency coordination amid persistent militant adaptability.[2][51]Major Operations and Engagements

Karachi Anti-Crime and Anti-Terrorism Campaigns

The Sindh Rangers were deployed to Karachi on September 5, 2013, at the request of the Sindh provincial government, initiating a targeted paramilitary operation to address escalating urban violence, including targeted killings, extortion, gang warfare, and terrorist activities linked to groups such as Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) affiliates and local criminal syndicates.[18] This deployment empowered the Rangers with police-like authority under the Anti-Terrorism Act, allowing intelligence-led raids, arrests, and encounters to dismantle networks in high-crime areas like Lyari, Orangi Town, and Malir. The operation focused on neutralizing operatives involved in over 2,000 annual targeted killings prior to 2013, which had crippled the city's economy and security.[52] Key phases included Operation Lyari, launched in 2013 against drug lords and militants like Uzair Baloch's gang, which controlled narcotics trafficking and used urban terrain for hit-and-run tactics, resulting in the capture of high-value targets and seizure of heavy weapons caches.[53] Rangers conducted over 10,000 intelligence-based operations by mid-2016, leading to 6,500 arrests, among them 1,236 designated terrorists and 848 professional target killers, alongside the elimination of approximately 500 criminals in verified encounters. These actions disrupted TTP urban cells responsible for bombings and assassinations, with recovered arms including AK-47s, grenades, and IED components.[54] The campaigns yielded measurable reductions in violence: targeted killings dropped by 91 percent and terrorism incidents by 72 percent in 2016 compared to peak pre-operation levels, restoring partial stability to Karachi's 20 million residents and enabling economic recovery in affected districts.[55] By 2023, marking a decade of sustained presence, the Rangers had conducted thousands of additional patrols and joint checkpoints with police, contributing to a broader decline in overall homicides from 2,500 in 2013 to under 500 annually in recent years, though sporadic flare-ups persisted due to underlying ethnic and sectarian tensions.[18] Empirical data from security briefings attribute this suppression to Rangers' rapid response capabilities and disruption of financing through extortion busts exceeding millions in recovered funds.[56]Indo-Pak Border Incidents and Responses

The Pakistan Rangers, particularly the Punjab Rangers, are deployed along the international border sectors opposite Indian states of Punjab, Rajasthan, and Gujarat, where they routinely monitor and respond to activities by the Indian Border Security Force (BSF). Their responses to border incidents include retaliatory firing during ceasefire violations and coordination for detainee exchanges.[57] In cases of inadvertent crossings amid heightened tensions, Pakistan Rangers have detained intruding personnel. On April 23, 2025, following the Pahalgam terror attack in Kashmir, BSF Constable Purnam Kumar Shaw crossed into Pakistani territory in Punjab sector and was apprehended by Rangers; he was returned to India on May 14, 2025, via a reciprocal exchange at the Wagah-Attari border post, where India handed over detained Pakistani Ranger Muhammadullah.[58][59] This exchange, confirmed by officials from both sides, exemplified de-escalation protocols despite ongoing accusations of violations.[60] Ceasefire violations along the international border have prompted direct engagements. On February 14, 2024, Pakistan Rangers opened unprovoked fire on BSF posts in Jammu's R S Pura area at approximately 5:50 PM, eliciting a retaliatory response from BSF troops that continued into the night.[61][62] Similar incidents, such as the May 2025 firing by Rangers on BSF positions, have been reported as triggers for Indian counteractions, though Pakistani sources attribute such exchanges to defensive measures against perceived aggression.[63] During the 2014–2015 border skirmishes, Rangers participated in heightened alert postures and flag meetings with BSF counterparts, leading to bilateral agreements for joint probes into violations and enhanced security measures to curb cross-border firing. These protocols aimed to reduce unprovoked attacks, which both forces accused the other of initiating, with over 200 violations recorded in that period by Indian assessments. Rangers' involvement underscored their role in maintaining border integrity through both kinetic responses and diplomatic channels at sector headquarters.Assistance in National Crises and Insurgencies

Pakistan Rangers have contributed to relief and rescue operations during major natural disasters, particularly floods impacting Punjab and Sindh provinces, where their operational mandates align with affected regions. During the 2010 floods in Sindh, Sindh Rangers established a dedicated flood relief center to coordinate assistance amid widespread inundation that displaced millions.[64] In 2022, amid nationwide flooding that affected over 33 million people and caused damages exceeding $30 billion, Punjab Rangers personnel executed emergency rescues, maintained coordination with other agencies, and prepared for expanded relief activities in vulnerable areas.[65] Rangers have also responded to localized crises, such as the 2014 Chenab River floods in Sialkot district, where units under Punjab Rangers command deployed to establish relief centers, set up medical camps, and support evacuation efforts in over 300 declared calamity-hit villages.[66] Similar support was provided during Cyclone Biparjoy in 2023, with Sindh Rangers aiding evacuations and rescue operations along the coastal belt.[67] These deployments leverage Rangers' rapid mobilization capabilities, including personnel trained in urban and rural search-and-rescue, though primary disaster response remains coordinated by the National Disaster Management Authority and Pakistan Army. Regarding insurgencies, Pakistan Rangers' involvement has been ancillary, focused on bolstering internal security rather than frontline combat, which is predominantly handled by the Pakistan Army and Frontier Corps in theaters like Swat Valley and Balochistan. No major documented deployments of Rangers to core insurgency zones such as Balochistan's separatist conflicts or the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan operations in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa have occurred, reflecting their statutory emphasis on eastern border defense and urban law enforcement. Their paramilitary structure enables ad-hoc support for maintaining order in peripherally affected areas during heightened militancy, but empirical records indicate limited direct engagement in sustained counter-insurgency campaigns.[68]Training, Equipment, and Capabilities

Recruitment and Training Regimens

Recruitment into the Pakistan Rangers, comprising the Punjab and Sindh wings, occurs through periodic open advertisements published in national newspapers and on official channels, targeting Pakistani citizens for various ranks such as sepoy, havildar, and sub-inspector.[69] Eligibility criteria emphasize physical fitness and basic education: candidates must be male (with limited female roles in some administrative capacities), aged 18 to 30 years (with potential relaxations up to 5 years for certain categories), hold at least a matriculation certificate for general duty positions, and meet minimum physical standards including a height of 5 feet 6 inches, chest girth of 32-33 inches with 1.5-2 inches expansion, and weight proportionate to BMI.[70] [69] The selection process begins with registration at designated recruitment centers during announced drives, followed by initial anthropometric screening for height, weight, and BMI compliance. Qualified applicants then undergo rigorous physical fitness tests, typically including a 2.4 km run completed within specified times (e.g., under 12 minutes for general ranks), push-ups (minimum 15-20), sit-ups (20-30), and chin-ups or pull-ups to assess endurance and strength. Successful candidates proceed to written examinations covering general knowledge, mathematics, English, and Pakistan studies, followed by interviews evaluating motivation and suitability, and final medical examinations to rule out disabilities or chronic conditions.[71] [72] Merit-based selection adheres to provincial quotas, prioritizing taller and fitter applicants where standards allow flexibility.[69] Upon selection, recruits enter basic training regimens at dedicated facilities, such as the Rangers Training Centre and School in Karachi for Sindh Rangers or equivalent centers for Punjab Rangers, lasting approximately 6 months for foundational courses. The program emphasizes physical hardening through daily regimens of running, obstacle courses, and endurance marches; precision drill for discipline and ceremonial duties; weapons handling with small arms like G3 rifles; and tactical instruction in border patrolling, crowd control, and counter-insurgency basics tailored to the Rangers' paramilitary role. Advanced modules may include anti-smuggling operations and urban security simulations, culminating in passing-out parades that certify operational readiness, as seen in the 27th Basic Recruits Training Course completion by 966 personnel in 2019.[73] [74] Specialized training for higher ranks extends this foundation with leadership and intelligence components, ensuring alignment with federal directives under the Interior Ministry.[75]Armaments, Vehicles, and Technological Assets

The Pakistan Rangers, as a paramilitary force, are equipped with standard infantry small arms akin to those used by the Pakistan Army, emphasizing reliability for border patrol and urban operations. The primary battle rifle is the 7.62×51mm Heckler & Koch G3, a selective-fire weapon produced under license in Pakistan, valued for its robustness in rugged terrains.[76] This rifle remains in widespread service across Pakistani paramilitary units, including Rangers, despite ongoing transitions to newer designs like the AK-103 in regular forces.[77] Support weapons include submachine guns such as the 9mm Heckler & Koch MP5 for close-quarters engagements in internal security roles, particularly in urban settings like Karachi.[78] Light machine guns, grenades, and sniper rifles supplement the arsenal, enabling Rangers to conduct counter-terrorism raids and border defense, though specific models beyond G3 variants are not publicly detailed in official disclosures. Pistols, typically 9mm models, serve as sidearms for personnel. Vehicles employed by the Rangers prioritize mobility and protection for rapid response. Armored personnel carriers like the Mohafiz, manufactured by Heavy Industries Taxila, provide ballistic protection against 7.62mm small arms fire and shell fragments, suited for internal security and convoy escort duties.[79] In 2001, the interior ministry directed Rangers to acquire armored vehicles to enhance operational capabilities amid rising threats.[80] More recently, in 2023, Sindh Rangers sought funding for quick response force vehicles and water cannons to bolster anti-riot measures.[81] Utility vehicles and modified trucks facilitate patrols along the Indo-Pakistani border and in flood-prone areas. Technological assets remain modest, focusing on basic enhancements rather than advanced systems. Rangers utilize communication radios and possibly night-vision devices for nighttime border vigilance, but no verified reports confirm deployment of drones or sophisticated surveillance tech exclusive to the force. Operations increasingly involve coordination with Army-provided assets during crises, such as flood relief in 2025.[82]Controversies and Criticisms

Allegations of Extrajudicial Actions and Human Rights Abuses

Pakistan Rangers, particularly the Sindh Rangers deployed in Karachi, have faced repeated allegations of extrajudicial killings during anti-crime and anti-terrorism operations launched in 2013. Critics, including political parties like the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), claim that Rangers personnel conducted "fake encounters," staging shootouts to execute suspects without due process, often targeting alleged militants or political rivals. In September 2015, MQM compiled a list of 46 party members purportedly killed deliberately by paramilitary forces, including Rangers, in such actions amid escalating tensions in Karachi.[83] These claims emerged during a period of expanded Rangers authority under the Anti-Terrorism Act and special ordinances, which granted powers for arrests and searches but drew scrutiny for insufficient oversight.[84] A prominent case occurred on June 8, 2011, when video footage captured Rangers personnel shooting Sarfaraz Shah, a 20-year-old unarmed man, at point-blank range in Karachi's Jinnah Park after he pleaded for mercy; Shah died from his wounds, prompting a government inquiry but limited accountability.[85] In another incident, MQM activist Aftab Ahmad died in April 2016 while in Sindh Rangers custody following his arrest on March 11; autopsy evidence and admissions from Rangers Director General Major General Bilal Akbar indicated severe torture during 90 days of interrogation, including beatings that caused internal injuries leading to cardiac arrest.[86] [87] [88] Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International urged independent probes into both cases, citing failures in judicial oversight and patterns of custodial abuse.[86] [87] Allegations extend to enforced disappearances and torture in Sindh province, where Rangers operations against nationalist groups like Jeay Sindh Muttahida Mahaz have been linked to abductions of activists protesting resource exploitation. Reports from 2016 detail instances of Sindhi individuals detained by Rangers and subjected to physical coercion to extract confessions or suppress dissent, though convictions remain rare due to military courts' jurisdiction and evidentiary challenges.[89] In Punjab, earlier 2004 Human Rights Watch documentation implicated Rangers in the repression of farmers on military lands, including shootings and beatings during land disputes in Okara district, where at least two tenant deaths were attributed to Rangers fire.[90] These claims, often from affected communities or opposition groups with histories of militancy, highlight tensions between security imperatives in volatile areas and adherence to legal standards, with international monitors noting systemic impunity in paramilitary actions.[91]Accusations of Political Bias and Overreach

The Pakistan Rangers have faced accusations of political bias primarily during their deployment in urban counter-terrorism operations, particularly in Karachi since 2013, where critics alleged selective targeting of the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), a major ethnic-based party representing Urdu-speaking Muhajirs. Opponents, including MQM leaders, claimed the Rangers' raids and arrests disproportionately focused on MQM activists while sparing allied political groups, portraying the force as an extension of the military establishment's efforts to weaken opposition parties.[92][93] A notable incident occurred on March 11, 2015, when Rangers raided MQM's Nine Zero headquarters in Karachi, detaining senior leaders and seizing weapons, which MQM described as a politically motivated assault violating democratic norms rather than a genuine anti-terrorism action.[92][94] Further allegations of overreach emerged from MQM's attempts to organize protests against Rangers' operations. On June 8, 2016, MQM accused the Rangers of illegally preventing a planned peaceful strike in Karachi by deploying forces to block rallies, framing it as suppression of legitimate political dissent under the guise of maintaining order.[95] The party contended that such interventions exceeded the Rangers' mandate under the Anti-Terrorism Act, 1997, which authorizes paramilitary action against extremism but not routine political policing.[95] Rangers spokespersons countered by accusing MQM's London-based leadership of inciting violence and operating a militant wing involved in extortion, yet critics maintained these claims served to justify partisan enforcement.[96][94] In broader contexts, Rangers have been criticized for involvement in quelling protests perceived as anti-government, raising concerns of bias toward the ruling coalition or federal authorities. During the 2017 Faizabad sit-in by Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) protesters in Islamabad, the government assigned Rangers to "handle" the demonstrators after weeks of blockade, leading to accusations of excessive force to protect entrenched power structures.[97] More recently, in September-October 2025, Rangers were deployed en masse—up to 10,000 personnel—in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoJK) to suppress protests against the Shehbaz Sharif government over demands for autonomy and economic relief, including internet blackouts and reported firing on crowds in Muzaffarabad, which activists labeled as overreach to stifle regional political mobilization.[98][99] These actions, while defended as necessary for public order, fueled narratives of Rangers acting as a federal tool against provincial or opposition dissent, often without proportional accountability.[100]Responses to Criticisms and Contextual Defenses

Pakistan Rangers officials have consistently maintained that allegations of extrajudicial actions during operations in Karachi, such as those under the 2013-ongoing targeted operations, stem from encounters with armed criminals and terrorists who resist arrest, asserting that force is used only in self-defense or when intelligence indicates imminent threats.[101] In official statements, the Rangers Sindh command emphasized that these actions are intelligence-driven and not targeted against any political, religious, or ethnic group, but rather against individuals involved in extortion, targeted killings, and terrorism linked to groups like Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan affiliates and urban militant networks.[102] Government spokespersons have echoed this, framing the Rangers' mandate under the Pakistan Rangers Ordinance of 1959 and subsequent empowerments via the Anti-Terrorism Act as legally sanctioned responses to a security vacuum where local police were infiltrated by criminal elements.[11] Contextually, the Rangers' operations in Karachi addressed a documented surge in violence, with over 3,000 fatalities annually from 2012 to 2014 due to sectarian killings, political assassinations, and gang warfare, which declined sharply post-deployment: targeted killings dropped by 70 percent and extortion by 85 percent by late 2015, with the overall crime index falling from 81.35 to 18.66 by 2020.[18] [101] [103] These outcomes, corroborated by government and independent security analyses, underscore the causal necessity of robust paramilitary intervention in a city previously described as a "no-go" zone for law enforcement, where weaker policing had enabled militant financing and safe havens.[104] Critics' reports from organizations like Human Rights Watch, while highlighting individual cases, often omit this pre-operation baseline of chaos—over 1,770 killings in 1995 alone escalating into thousands by the 2010s—and rely on unverified activist testimonies amid a landscape of politicized accusations from affected parties like the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM).[7] Regarding accusations of political bias or overreach, Rangers leadership has rejected claims of selective targeting, pointing to arrests and neutralizations across ethnic and partisan lines, including MQM workers involved in racketeering, as part of a federally directed National Action Plan against terrorism that dismantled over 7,000 criminal hideouts by 2015 without favoring any administration.[101] Interior Ministry officials have defended extensions of Rangers' powers, arguing they prevent state capture by hybrid criminal-political networks, with empirical reductions in street crime and militancy validating the approach despite procedural lapses in isolated encounters.[105] In border contexts, such as Indo-Pak incidents, Rangers actions are justified as proportionate responses to infiltration attempts, smuggling, and ceasefire violations, enabling bilateral flag meetings and personnel exchanges that have de-escalated tensions, as seen in the 2025 repatriation of cross-border troops.[60] [106] This framework aligns with the force's foundational role in maintaining frontier order against non-state threats, where restraint could exacerbate vulnerabilities exploited by groups like Lashkar-e-Taiba.[11] While international human rights bodies demand independent probes into specific deaths, Pakistani authorities counter that internal inquiries and judicial oversight suffice in a counter-insurgency setting, noting low prosecution rates for Rangers personnel reflect evidentiary challenges in militant-linked cases rather than impunity, with broader security gains—such as curtailed terrorist financing—outweighing anecdotal abuses when weighed against pre-intervention death tolls exceeding 30,000 nationwide from terrorism since 2001.[45] Such defenses prioritize causal realism: unchecked urban and border threats posed existential risks to state stability, rendering the Rangers' high-risk engagements a pragmatic bulwark, albeit one requiring ongoing accountability mechanisms to mitigate excesses.[107]Achievements and Strategic Impact

Contributions to National Security and Stability

Pakistan Rangers have played a pivotal role in securing the nation's eastern border with India, spanning over 2,000 kilometers, by conducting patrols to prevent illegal crossings, smuggling of arms and narcotics, and potential infiltrations by hostile elements. Their operations have routinely resulted in the apprehension of smugglers and seizure of contraband; for instance, in September 2025, Sindh Rangers launched a major crackdown that eradicated smuggling networks in the region, continuing efforts to dismantle such activities entirely.[108] Similarly, joint operations with customs in October 2025 recovered smuggled goods valued at over Rs10.8 million, including foreign cigarettes and betel nut, demonstrating their effectiveness in disrupting illicit trade that undermines economic stability.[109] These actions contribute to national stability by curtailing revenue losses estimated in billions annually from smuggling and reducing the flow of weapons that could fuel internal insurgencies. In urban internal security, the Rangers' deployment in Karachi under the ongoing operation, initiated in 2013, has significantly enhanced stability by targeting organized crime, political violence, and terrorism. The intervention led to a sharp decline in terrorist incidents and target killings, transforming the city's security landscape from one plagued by criminal syndicates and extremists to a more controlled environment.[110] [18] Post-2010 enhancements in their mandate allowed for proactive policing, including patrols and pickets, which quelled violent extremism and restored order in Pakistan's largest metropolis, thereby preventing broader destabilization that could spill over nationally.[9] Beyond direct enforcement, Rangers support counterterrorism efforts by assisting in the disruption of militant networks and providing rapid response capabilities, as seen in their role in foreign peacekeeping and domestic anti-terror operations. Their paramilitary structure, with approximately 50,000 personnel focused on border and internal threats, bridges gaps in regular police capacity, fostering long-term stability through sustained presence and intelligence-driven actions.[20] This multifaceted approach has empirically reduced urban violence metrics in key areas, underscoring their integral contribution to Pakistan's overall security architecture despite persistent challenges from asymmetric threats.[9]Effectiveness Metrics and Comparative Analysis

The Sindh Rangers' targeted operation in Karachi, initiated on September 5, 2013, yielded measurable reductions in violent crime through intensive intelligence-led raids and arrests. In 2016, extortion cases fell by 93% from 1,524 to 99, targeted killings by 91% from 965 to 86, kidnappings for ransom by 86%, and terrorism incidents by 72% from 57 to 16.[55] These outcomes stemmed from 1,992 operations that year, resulting in 2,847 arrests, seizure of 1,845 weapons, apprehension of 350 terrorists from banned outfits, and detention of 446 suspects linked to targeted killings, including 348 affiliated with political parties.[55] By 2017, the deployment of approximately 15,000 Rangers with expanded powers for warrantless searches correlated with zero bombings and only five kidnappings in Karachi, alongside an improvement in the city's Numbeo crime index ranking from 6th most dangerous globally in 2013 to 50th in 2017.[111]| Crime Category | 2013 Incidents | 2016 Incidents | Percentage Decrease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extortion | 1,524 | 99 | 93% |

| Targeted Killings | 965 | 86 | 91% |

| Kidnappings for Ransom | Not specified quantitatively | Not specified quantitatively | 86% |

| Terrorism Incidents | 57 | 16 | 72% |