Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

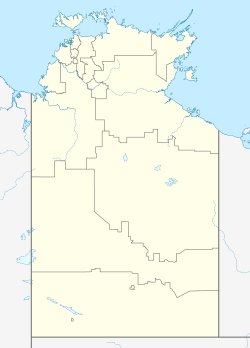

Papunya

View on Wikipedia

Papunya (Pintupi-Luritja: Warumpi)[4] is a small Indigenous Australian community roughly 240 kilometres (150 mi) northwest of Alice Springs (Mparntwe) in the Northern Territory, Australia. It is known as an important centre for Contemporary Indigenous Australian art, in particular the style created by the Papunya Tula artists in the 1970s, referred to colloquially as dot painting. Its population in 2016 was 404.

Key Information

History

[edit]Pintupi and Luritja people were forced off their traditional country in the 1930s and moved into Hermannsburg (Ntaria) and Haasts Bluff, where there were government ration depots. There were often tragic confrontations between these people, with their nomadic hunter-gathering lifestyle, and the cattlemen who were moving into the country and over-using the limited water supplies of the region for their cattle.[citation needed]

The Australian Government built a water bore and some basic housing at Papunya in the 1950s to provide room for the increasing populations of people in the already-established Aboriginal communities and reserves. The community grew to over a thousand people in the early 1970s and was plagued by poor living conditions, health problems, and tensions between various tribal and linguistic groups. These festering problems led many people, especially the Pintupi, to move further west closer to their traditional country. After settling in a series of outstations, with little or no support from the government, the new community of Kintore was established about 250 kilometres (160 mi)west of Papunya in the early 1980s.[citation needed]

The term "Finke River Mission" was initially an alternative name for the mission at Hermannsburg, but this name was later often used to include the settlements at Haasts Bluff, Areyonga and, later, Papunya. It now refers to all Lutheran missionary activity in Central Australia since the first mission was established at Hermannsburg in 1877.[5][6][7]

Description and demographics

[edit]It is now home to a number of displaced Aboriginal people, mainly from the Pintupi and Luritja groups. At the 2016 Australian census, Papunya had a population of 404.[3]

The predominant religion at Papunya is Lutheranism, with 310 members, or 78.7% of the population, based on the 2016 census.[3]

It is the closest town to the Australian continental pole of inaccessibility. Papunya is on restricted Aboriginal land and requires a permit to enter or travel through.[citation needed]

Warumpi Band were an Australian country and Aboriginal rock group which formed in Papunya.[citation needed]

Art

[edit]Papunya Tula

[edit]During the 1970s a striking new art style emerged in Papunya, which by the 1980s began to attract national and then international attention as a significant Indigenous art movement, colloquially known as dot painting. Leading exponents of the style, who belonged to the Papunya Tula art cooperative founded in Papunya in 1972, included Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, Billy Stockman Tjapaltjarri, Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, Turkey Tolson Tjupurrula, and Pansy Napangardi.[8] The company now operates out of Alice Springs,[9] and covers an enormous area, extending into Western Australia, 700 kilometres (430 mi) west of Alice Springs.[10]

Papunya Tjupi Arts

[edit]Papunya Tjupi Arts, a community-based, 100% Aboriginal-owned arts organisation, commenced in 2007,[11] and as of March 2021[update] hosts around 150 artists, many of whose works are featured in exhibitions and galleries around the world.[12] In 2009, Michael Nelson Tjakamarra (Kumantje Jagamara) became the artist leader at the arts centre.[13]

Artists include Doris Bush Nungarrayi, Maureen Poulson, Charlotte Phillipus Napurrula, Tilau Nangala, Mona Nangala, Nellie Nangala, Carbiene McDonald Tjangala, Martha McDonald Napaltjarri, Candy Nelson Nakamarra, Dennis Nelson Tjakamarra, Narlie Nelson Nakamarra, Isobel Major Nampatjimpa, Isobel Gorey, Mary Roberts, Beyula Putungka Napanangka, Watson Corby among others.[14]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Papunya (suburb and locality)". Australian Census 2021 QuickStats. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Papunya (suburb and locality)". Australian Census 2021.

- ^ a b c Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Papunya (L) (Urban Centre/Locality)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ "Papunya | MacDonnell Council".

- ^ George, Karen; George, Gary (17 March 2017). "Finke River Mission - Glossary Term - Northern Territory". Find & Connect. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ "About". Finke River Mission. 29 October 2018. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ "Finke River Mission 135th Anniversary". Lutheran Church of Australia. Archived from the original on 24 June 2015.

- ^ Papunya Painting: The Artists Archived 25 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine, National Museum of Australia

- ^ "Contact". Papunya Tula Artists Pty. Ltd. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "History". Papunya Tula Artists Pty. Ltd. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ Sarah White (June 2013). "Art Centre: Papunya Tjupi Arts". Art Collector (64). Gadfly Media. Archived from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ "Papunya Tjupi Aboriginal Arts". tjupiarts.com.au. Papunya Tjupi Arts. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ Fairley, Gina (26 November 2020). "Vale: Michael Nelson Jagamara AM and Kunmanara Lewis". ArtsHub Australia. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "Doris Bush". tjupiarts.com.au. Papunya Tjupi Arts. Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Desart: Aboriginal art and craft centres of Central Australia. (1993) Co-ordinator Diana James DESART, Alice Springs. ISBN 0-646-15546-6

- Papunya Tula: Art of the Western Desert. (1992) Geoffrey Bardon. Tuttle Publishers. ISBN 0-86914-160-0

- Papunya Tula: Genesis and Genius. (2001) Eds. Hetti Perkins and Hannah Fink. Art Gallery of NSW in association with Papunya Tula Artists. ISBN 0-7347-6310-7.

- "Papunya Painting: Further Reading". National Museum of Australia.

External links

[edit]- Papunya Painting: Out of the Desert An online exhibition of Papunya artworks held by the National Museum of Australia. The website includes the works, biographies of the artists, installation images and a bibliography.

Papunya

View on GrokipediaPapunya is a remote Aboriginal community in Australia's Northern Territory, established in 1959 as a government settlement to house nomadic Pintupi, Luritja, and other Western Desert peoples relocated from ration depots such as Haasts Bluff.[1][2] Located approximately 240 kilometres west of Alice Springs on the Haasts Bluff Aboriginal Land Trust, it serves as a hub for speakers of Luritja, Warlpiri, and Pintupi languages.[3][4] As of the 2021 Australian Bureau of Statistics census, Papunya had a population of 438, with 88.8% identifying as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander.[5] The settlement was created under policies aimed at concentrating dispersed Indigenous groups for administrative control and assimilation into Western society, resulting in rapid population growth to over 1,400 by 1970 amid cultural clashes and social challenges.[3][6] Papunya's defining cultural achievement emerged in 1971, when schoolteacher Geoffrey Bardon collaborated with senior men to paint murals depicting traditional Dreamtime stories on school walls using acrylic paints, evolving into portable works on boards and canvases that concealed sacred elements with dot patterns.[3] This initiative birthed the Papunya Tula artists' collective in 1972, pioneering the Western Desert art movement and enabling economic independence through global sales while revitalizing cultural transmission.[7][3]

Today, Papunya remains a key center for contemporary Indigenous art production, with Papunya Tula continuing as an Aboriginal-owned enterprise, though the community grapples with ongoing issues of remoteness, health, and self-determination in land rights and governance.[7][8]

Geography and Environment

Location and Physical Features

Papunya lies approximately 240 kilometers northwest of Alice Springs in the Northern Territory of Australia, within the MacDonnell Regional Council area, on land traditionally occupied by Pintupi and Luritja peoples.[5][3] This positioning in central Australia's arid interior underscores the community's remoteness, with vast desert expanses limiting connectivity and self-sufficiency by complicating supply chains and mobility.[9] Access to Papunya occurs mainly via unsealed roads branching from the Tanami Highway, rendering travel vulnerable to seasonal flooding that frequently isolates the settlement.[10][11] Nearby settlements, such as Kintore (Walungurru) to the west along the Kintore Road, share similar desert isolation, approximately 290 kilometers distant, further emphasizing the sparse human distribution across the region.[12][13] The absence of major rivers compels reliance on groundwater extracted from bores, constraining availability in this water-scarce environment.[14] The terrain features parallel sandhills, ephemeral claypans, and infrequent rock holes, elements integral to Pintupi and Luritja Tjukurpa (Dreaming) stories that encode knowledge of survival in aridity.[15] These geological formations support minimal vegetation like spinifex and desert oaks but permit little resource extraction or agriculture due to pervasive dryness and nutrient-poor soils, reinforcing dependence on external provisioning.[16]