Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Parantaka I

View on Wikipedia

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

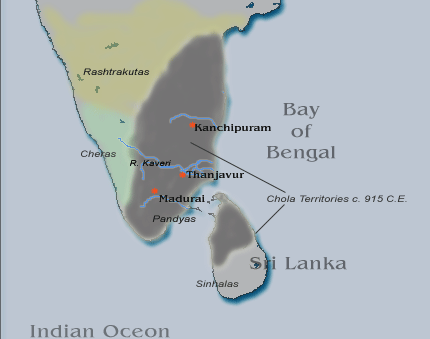

Parantaka Chola I (Tamil: பராந்தக சோழன்; 873–955) was the Chola emperor from 907 until his death in 955. During his 48-year long reign, he annexed the Pandyas by defeating Rajasimhan II, and in the Deccan won the Battle of Vallala against Rashtrakutas in 911.[2][3] The best part of his reign was marked by increasing success and prosperity.

Key Information

Invasion of the Pandya kingdom

[edit]Parantaka I continued the expansion started by his father, and invaded the Pandya kingdom in 915. He captured the Pandyan capital Madurai and assumed the title Madurain-konda (Capturer of Madurai). The Pandyan ruler Maravarman Rajasinha II sought the help of Kassapa V of Anuradhapura, who sent an army to his aid. Parantaka defeated the combined army at the Battle of Vellore, a decisive victory for the Cholas,[4] but this victory was narrow.[5]At the battle of Vellur, during the first attempt, Cholas defeated Pandyan army and slained the Lankan army. According to the Chronicles,[specify] Ceylon troops made the second attempt in this most of the Ceylonese troops have caught a plague and caused the death of most of the troops including the commander this causes the remaining Ceylonese troops to be recalled by King Kassapa V. This second attempt was not mentioned in Chola sources.[6] Then Pandya king fled into exile in Sri Lanka and Parantaka I completed his conquest of the entire Pandya country.[7][8]

Parantaka spent many years in the newly conquered country reducing it to subjugation, and when he felt he had at last achieved his aim, he wanted to celebrate his victory by a coronation in Madurai in which he was to invest himself with the insignia of Pandyan monarchy.[citation needed] However he was failed in this attempt by the Pandyan king, who had carried them away and left them in the safe custody of the Lankan king.[citation needed]

Lankan Expedition

[edit]Towards the end of his reign, Parantaka tried to capture Pandya regalia back by invading Lanka, although the Colas were victorious in battle and conquered the northern provinces, but failed to take them.[9][10][11][12][13] Now at that this time the Senapati here (in Ceylon) was absent in a rebellious border province. The king had him fetched and sent him forth to begin the war. The Senapati set forth, delivered battle and fell in the fight. Thereupon the king (Udaya) took the crown and the rest and betook himself to Rohana. The chola troops marched but finding no way of entering Rohana, they turned and betook themselves from here to their own country but Chola troops made off with other booties allegedly there was a counter invasion by Ceylon and they were able to recover the loot but this is not mentioned by the Cholas.[13][14][15] Mahavamsa also records that the Lankan king Udaya IV took the Pandya crown and the jewels and hid himself in the Rohana hills. After his exploits in the Pandya country and in Lanka, he took the title of Maduraiyum Eelamum Konda Parakesarivarman – Parakesarivarman who conquered Madurai and Sri Lanka.

War against the Rashtrakutas

[edit]Aditya I had two sons namely Parantaka I and Kannara Deva. The eldest son was Parantaka, born to a Chera wife; the youngest son was Kannara Devan, born to a Rashtrakuta wife. After the death of Aditya I, Rashtrakuta king Krishna II tried to exert his influence in the Chola country by placing his grandson Kannara Deva on the throne. But in 907 CE, Parantaka became the king. Disappointed by this, Krishna II invaded the Chola country. On Rashtrakuta side, prince Indra III lead the battle, while the Chola side was led by King Parantaka and Prince Rajaditya. In the year 911, in the Battle of Vallala,[2][16] a large number of Rashtrakuta soldiers died and their army began to weaken. Krishna II withdrew and his forces retreated. The Cholas advanced further and attacked the Rashtrakutas and chased away from their territory. Eventually the Cholas defeated the Rashtrakutas. Parantaka Chola's early series of victories would also includes this Rashtrakuta War.

Legacy

[edit]At the height of his success, Parantaka's dominions comprised almost the whole of the Tamil country right up to Nellore in Andhra Pradesh. It is clear from other Chola grants that Parantaka I was a great militarist who had made extensive conquests. He may have had it recorded, but those records are lost to us. He is known to have defeated the kings of the Deccan kingdoms by 912, and temporarily completed the conquests started by his father Aditya. Later in 949, Rashtrakuta king Krishna III waged war against Cholas, so Parantaka sent an army under his son Rajaditya. Subsequently, the Cholas were defeated, and crown prince Rajaditya was killed on the battlefield while upon an elephant.[17]

Civic and religious contributions

[edit]Although Parantaka I was engaged for the greater part of his long reign in warlike operations, yet he was not unmindful of the victories of peace. The internal administration of his country was a matter in which he took a keen interest. He laid out the rules for the conduct of the village assemblies in an inscription. The village institutions of South India, of course, date from a much earlier period than that of Parantaka I, but he introduced many salutary reforms for the proper administration of local self-Government.[citation needed]

The copper-plate inscriptions detail Parantaka I's promotion of agricultural prosperity by the digging of numerous canals all over the country.[citation needed]

He also utilised the spoils of war to donate to numerous temple charities. He is reported to have covered the Chidambaram Siva Temple with a golden roof.[citation needed] He was a devout Saiva (follower of Siva) in religion.[citation needed]

Personal life

[edit]From his inscriptions we can gather a few details about Parantaka's personal life. He had many wives, of whom no fewer than eleven appear in the inscriptions. He was religious but secular and encouraged various faiths. We find various members of his family building temples and regularly making donations to various shrines across the kingdom. Kotanta Rama, incidental with Rajaditya, was the eldest son of Parantaka I. There is an inscription of him from Tiruvorriyur making a donation for some lamps during the 30th year of his father.[18] Besides him he had several other sons; Arikulakesari, Gandaraditya and Uttamasili.

Parankata had the Chera Perumals as his close allies and the relationship was further strengthened by two marriages. The king is assumed to have married two distinct Chera princesses (the mothers of his two sons, Rajaditya and Arinjaya).[19][20]

A member of the retinue of pillaiyar (prince) Rajadittadeva gave a gift to the Vishnu temple at Tirunavalur/Tirumanallur in the 32nd year of Parantaka I.[21] Tirunavalur was also known as "Rajadittapuram" after Rajaditya.[22] It is assumed that a large number of warriors from the aristocratic families of the Chera kingdom were part of the contingent of this Chera-Chola prince.[23] In the 39th year of Parantaka I, his daughter-in-law, Mahadevadigal, a queen of Rajaditya and the daughter of Lataraja donated a lamp to the temple of Rajadityesvara for the merit of her brother.[24] He had at least two daughters: Viramadevi and Anupama. Uttamasili does not appear to have lived long enough to succeed to the Chola throne.

He bore numerous epithets such as Viranarayana, Virakirti, Vira-Chola, Vikrama-Chola, Irumadi-Sola (Chola with two crowns alluding to the Chola and the Pandya kingdoms), Devendran (lord of the gods), Chakravartin (the emperor), Panditavatsalan (fond of learned men), Kunjaramallan (the wrestler with elephants) and Surachulamani (the crest jewel of the heroes).[citation needed]

Parantaka I died in 955. His second son Gandaraditya succeeded him.

Inscriptions

[edit]

The following is an inscription of Parantaka I from Tiruvorriyur. It is important as it shows that his dominions included regions beyond Thondaimandalam:

..record of the Chola king Maduraikonda Parakesarivarman(Parantaka) dated in his 34th year. Records gift of lamp to the temple of Tiruvorriyur Mahadeva by Maran Parameswaran alias Sembiyan Soliyavarayan of Sirukulattur in Poyyurkurram, a sub-division of Tenkarai-nadu. Refers to a military officer who destroyed Sitpuli and destroyed Nellore.[25]

Here we have his son Arinjaya making a donation. Once again it is from Tiruvorriyur:

On the eleventh slab. Records in the 30th year of Maduraikonda Parakesarivarman(Parantaka) dated in his 30th year, gift of gold for a lamp by Arindigai-perumanar, son of Chola-Perumanadigal (i.e Parantaka), to the god Siva at Adhigrama.[26]

We also have several inscriptions of his son Rajaditya from Tirunavalur. One such inscription is the following from the temple of Rajadityesvara in Tirunavalur. The temple was also called Tiruttondîsvaram:[27]

A record in the 29th year of the Chola king Maduraikonda Parakesarivarman. Records gift of 20 sheep for offerings and of two lamps to the shrines of Rajadityesvara and Agastyesvara by a servant of Rajadityadeva.[28]

Chola-Chera Perumal relations (c. 9th-10th centuries CE)

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ S. R. Balasubrahmanyam. Volume 1 of Early Chola Art, S. R. Balasubrahmanyam. Asia publ. house, 1966. p. 165.

- ^ a b K.A., Nilakanta Sastri (1955). A History of South India from Prehistoric to the Fall of Vijayanagar. Oxford University Press. pp. Page=168.

- ^ Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 46–49. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- ^ Nilakanda Sastry,The Colas, pg.123

- ^ Wijetunge, Sirisaman (2016). The ancient heritage of Sri Lanka part 1 (1st ed.). Samudra Book Publications. p. 149. ISBN 978-955-680-538-3.

- ^ Nilakanda Sastry,The Colas, pg.122

- ^ Cholas I.

- ^ Historical Inscriptions Of Southern INida. BRAOU, Digital Library Of India. Kitabistam,Allahabad.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ GEIGER, WILH. "The Trustworthiness of Mahavamsa". THE Indian Historical Quarterly: 221.

- ^ Cholas I. p. 154.

- ^ Sastri, K. Nilakanta (July 1974). The Pandyan Kingdom. Ind-U. S. Incorporated. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-88253-426-8.

- ^ Pillay, Kolappa Pillay Kanakasabhapathi (1963). South India and Ceylon. University of Madras. pp. 62–63.

- ^ a b Spencer, George W. (1976). "The Politics of Plunder: The Cholas in Eleventh-Century Ceylon". The Journal of Asian Studies. 35 (3): 408–409. doi:10.2307/2053272. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 2053272.

- ^ Spencer 1976, p. 409

- ^ Cholas I. p. 148.

- ^ Early Chola Temples Parantaka I To Rajaraja I Ad 907 985.

- ^ Cholas I.

- ^ South Indian shrines: illustrated, page 56

- ^ George Spencer, 'Ties that Bound: Royal Marriage Alliance in the Chola Period', Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Asian Studies (Hong Kong: Asian Research Service, 1982), 723.

- ^ S. Swaminathan. The early Chōḷas history, art, and culture. Sharada Pub. House, 1998. p. 23.

- ^ Early Chola temples: Parantaka I to Rajaraja I, A.D. 907–985, page 64

- ^ South Indian Inscriptions: Miscellaneous inscriptions in Tamil (4 pts. in 2), page 198

- ^ Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala: Brahmin Oligarchy and Ritual Monarchy: Political and Social Conditions of Kerala Under the Cēra Perumāḷs of Makōtai (c. AD 800 - AD 1124). Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 96-100.

- ^ Epigraphia Indica and record of the Archæological Survey of India, Volume 7, page 167

- ^ South Indian shrines: illustrated, page 55

- ^ South Indian shrines: illustrated, page 57

- ^ A topographical list of inscriptions in the Tamil Nadu and Kerala states, Volume 2, page 393

- ^ A topographical list of the inscriptions of the Madras Presidency, collected till 1915, page 232

References

[edit]- Venkata Ramanappa, M. N. (1987). Outlines of South Indian History. (Rev. edn.) New Delhi: Vikram.

- Early Chola temples: to Rajaraja I, A.D. 907–985 By S. R. Balasubrahmanyam

- South Indian Inscriptions: Miscellaneous inscriptions in Tamil (4 pts. in 2) By Eugen Hultzsch, Hosakote Krishna Sastri, V. Venkayya, Archaeological Survey of India

- A topographical list of the inscriptions of the Madras Presidency, collected till 1915: with notes and references, Volume 1 By Vijayaraghava Rangacharya

- A topographical list of inscriptions in the Tamil Nadu and Kerala states, Volume 2 By T. V. Mahalingam

- Nilakanta Sastri, K. A. (1935). The CōĻas, University of Madras, Madras (Reprinted 1984).

- Nilakanta Sastri, K. A. (1955). A History of South India, OUP, New Delhi (Reprinted 2002).

- South Indian shrines: illustrated By P. V. Jagadisa Ayyar