Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

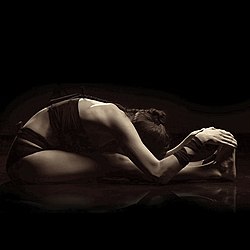

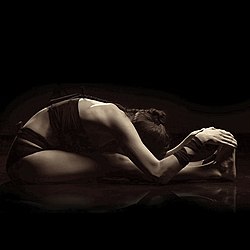

Paschimottanasana

View on Wikipedia

Pashchimottanasana (Sanskrit: पश्चिमोत्तानासन, romanized: paścimottānāsana), Seated Forward Bend,[1] or Intense Dorsal Stretch[2] is a seated forward-bending asana in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise. Janusirsasana is a variant with one knee bent out to the side; Upavishthakonasana has the legs straight and wide apart.

Etymology and origins

[edit]

The name Paschimottanasana comes from three Sanskrit words. Paschima (पश्चिम, paścima) has the surface meaning of "West" or "the back of the body".[3] In terms of the subtle body (as in the Yogabīja), it means the central energy channel, the sushumna nadi, which runs the length of the backbone.[4] Uttana (उत्तान, uttāna) means "intense stretch" or "straight" or "extended".[5] Asana (आसन, āsana) meaning "posture" or "seat".[6] The pose is described in the 15th-century Hatha Yoga Pradipika, chapter 1, verses 28-29.

The name Dandasana (Sanskrit: दण्डासन; IAST: daṇḍāsana) is from Sanskrit दण्ड daṇḍa meaning "stick" or "staff".[7] The pose is not found in the medieval hatha yoga texts. The 19th century Sritattvanidhi uses the name Dandasana for a different pose, the body held straight, supported by a rope. The yoga scholar Norman Sjoman notes, however, that the traditional Indian Vyayama gymnastic exercises include a set of movements called "dands", similar to Surya Namaskar and to the vinyasas used in modern yoga.[8]

The name Janusirsasana (Sanskrit: जानु शीर्षासन; IAST: jānu śīrṣāsana) comes from the Sanskrit जानु (jānu) meaning "knee" and शीर्ष (śīrṣa) meaning "head".[9] The pose is a modern one, first seen in the 20th century. It is described in Krishnamacharya's 1934 Yoga Makaranda,[10] and in the works of his pupils, B. K. S. Iyengar's 1966 Light on Yoga[11] and Pattabhi Jois's Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga.[12][9]

The name Upavishthakonasana (Sanskrit: उपविष्टकोणासन); IAST: upaviṣṭa koṇāsana) is from the Sanskrit उपविष्ट (upaviṣṭa) meaning "open" and कोण (koṇa) meaning "angle".[13] It is not found in medieval hatha yoga, but is described in Light on Yoga.[14] It is independently described under a different name, Hastapadasana ("Hand-to-Foot Pose"[a]) in Swami Vishnudevananda's 1960 Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga, suggesting an older origin.[15]

Description

[edit]Paschimottanasana is entered from Dandasana (seated Staff pose) by bending forward from the hips without straining and grasping the feet or lower legs. A strap may be placed around the feet and grasped in the hands if the back is stiff. The head may be rested on a folded blanket or bolster, which may be raised on a small stool if necessary.[16][17] People who have difficulty bending their backs should exercise caution when performing this asana.[18]

Variations

[edit]Dandasana or "Staff pose" has the legs extended along the floor and the body straight upright, with the palms or fingertips on the ground.[19] People who cannot sit on the floor like this can sit on a folded blanket.[20]

Janusirsasana or "Head to knee pose" has one leg extended with toes pointing upward, and the other leg bent with knee pointing away from the straight leg and the sole of the foot in by the groin. The torso folds straight forwards over the extended leg.[11][21]

Urdhva Mukha Paschimottanasana, also called Ubhaya Padangusthasana, is a balancing form of the pose, legs and hands pointing upwards.[22][23]

Parivritta Paschimottanasana is the reversed or twisted form of the pose, the body twisted to one side and the hands reversed, so that if the body is turned to the left, the right hand grasps the left foot, the right elbow is over the left knee, and the left hand grasps the right foot.[24]

Trianga Mukhaikapada Paschimottanasana has one leg bent as in Virasana.[25]

Wide-Legged Forward Bend (Prone Paschimottanasana) Open your legs wider than hip-width apart and fold forward. This variation targets the inner thighs while still stretching the back.[26]

Baddha Padma Paschimottanasana[27] has one leg crossed over the other as in Padmasana.[28]

Upavishthakonasana or "wide-angle seated forward bend"[20] has both legs straight along the ground, as wide apart as possible, with the chin and nose touching the ground.[13][14][29][30] Parsva Upavishthakonasana (to the side) has the body facing one leg, and the hands both grasping the foot of that leg, without raising the opposite hip.[31] Urdhva Upavishthakonasana (upwards) is similar to Navasana but with legs wide. It has the first and second fingers grasping the big toes, the legs wide apart, straight, and raised to around head height; the body is tilted back slightly to balance on the sitting bones. The pose can be practised with a strap around each foot if the legs cannot be straightened fully in the position; a rolled blanked can be placed behind the buttocks to assist with balancing.[32] If you have a back injury, a knee injury, or high blood pressure, avoid this asana.[33]

-

Dandasana

-

Janusirsasana

-

Upavishthakonasana

See also

[edit]- Uttanasana, a standing forward bend

Notes

[edit]- ^ Hastapadasana is otherwise a synonym of the standing Forward Bend, uttanasana.

References

[edit]- ^ "Yoga Journal - Seated Forward Bend". Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- ^ "Asanas - Forward Bending Poses". About Yoga. Archived from the original on 2010-12-16. Retrieved 2011-06-25.

- ^ Lark, Liz (15 March 2008). 1,001 Pearls of Yoga Wisdom: Take Your Practice Beyond the Mat. Chronicle Books. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-8118-6358-2. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- ^ Birch, Jason (2024). "Annotated Translation". Āsanas of the Yogacintāmaṇi: The Largest Premodern Compilation on Postural Practice. Paris and Pondicherry: École française d'Extrême-Orient and Institut français de Pondichéry. p. 163.

- ^ "Paschimottanasana". Ashtanga Yoga. Archived from the original on 2011-04-13. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- ^ Sinha, S. C. (1 June 1996). Dictionary of Philosophy. Anmol Publications. p. 18. ISBN 978-81-7041-293-9.

- ^ "Dandasana". Ashtanga Yoga. Archived from the original on 13 February 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ Sjoman 1999, pp. =44, 50, 78, 98–99.

- ^ a b "Janu Shirshasana A". Ashtanga Yoga. Retrieved 2011-04-09.

- ^ Krishnamacharya, Tirumalai (2006) [1934]. Yoga Makaranda. Translated by Ranganathan, Lakshmi; Ranganathan, Nandini. pp. 77–83.

- ^ a b Iyengar, B. K. S. (1979) [1966]. Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika. Unwin Paperbacks. pp. 148–151. ISBN 978-1855381667.

- ^ Sjoman 1999, pp. 88, 100, 102.

- ^ a b Mehta 1990, p. 65.

- ^ a b Iyengar 1979, pp. 163–165.

- ^ Sjoman 1999, p. 88.

- ^ Iyengar 1991, pp. 166–170.

- ^ Mehta 1990, p. 64.

- ^ Kapadia, Praveen (2002). Yoga Simplified (1st ed.). Hyderabad, India: Gandhi Gyan Mandir Yoga Kendra. pp. 124–125.

- ^ "Staff Pose". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ a b Rosen, Richard (28 August 2007). "Wide-Angle Seated Forward Bend". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ Saraswati, Swami Satyananda (2003). Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha. Nesma Books India. pp. 235–236. ISBN 978-81-86336-14-4.

- ^ "Urdhva-Mukha Paschimottanasana". Ashtanga Yoga. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ Iyengar 1991, p. 173.

- ^ Iyengar 1991, pp. 170–173.

- ^ Iyengar 1991, pp. 156–157.

- ^ sonu (2024-12-22). "Seated Forward Bend Pose (Paschimottanasana)". Retrieved 2025-01-26.

- ^ "Ardha Baddha Padma Paschimottanasana". Yoga Vastu. October 2020.

- ^ Iyengar 1991, pp. 153–156.

- ^ Botur, Amanda. "Wide-Angle Seated Forward Bend: Upavistha Konasana". Yoga Today. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ^ "Wide-Angle Seated Forward Bend - Upavishta Konasana". Ekhart Yoga. 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ^ "Parsva Upavistha Konasana (Side Seated Wide Angle Pose)". Yoga Vastu. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ "Upward Facing Wide-Angle Seated Pose - Urdhva Upavistha Konasana". Ekhart Yoga. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ "10 Benefits of Seated Forward Bend (paschimottanasana)". Namaste yoga school. 27 January 2023.

Sources

[edit]- Iyengar, B. K. S. (1991) [1966]. Light on Yoga. Thorsons. pp. 166–170. ISBN 978-1855381667.

- Mehta, Silva; Mehta, Mira; Mehta, Shyam (1990). Yoga: The Iyengar Way. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0863184208.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sjoman, Norman E. (1999) [1996]. The Yoga Tradition of the Mysore Palace. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-389-2.