Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

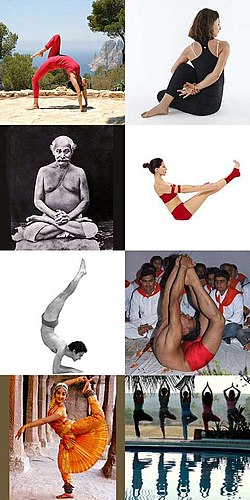

Asana

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

An āsana (Sanskrit: आसन) is a body posture, originally and still a general term for a sitting meditation pose,[1] and later extended in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise, to any type of position, adding reclining, standing, inverted, twisting, and balancing poses. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali define "asana" as "[a position that] is steady and comfortable".[2] Patanjali mentions the ability to sit for extended periods as one of the eight limbs of his system.[2] Asanas are also called yoga poses or yoga postures in English.

The 10th or 11th century Goraksha Sataka and the 15th century Hatha Yoga Pradipika identify 84 asanas; the 17th century Hatha Ratnavali provides a different list of 84 asanas, describing some of them. In the 20th century, Indian nationalism favoured physical culture in response to colonialism. In that environment, pioneers such as Yogendra, Kuvalayananda, and Krishnamacharya taught a new system of asanas (incorporating systems of exercise as well as traditional hatha yoga). Among Krishnamacharya's pupils were influential Indian yoga teachers including Pattabhi Jois, founder of Ashtanga (vinyasa) yoga, and B.K.S. Iyengar, founder of Iyengar yoga. Together they described hundreds more asanas, revived the popularity of yoga, and brought it to the Western world. Many more asanas have been devised since Iyengar's 1966 Light on Yoga which described some 200 asanas. Hundreds more were illustrated by Dharma Mittra.

Asanas were claimed to provide both spiritual and physical benefits in medieval hatha yoga texts. More recently, studies have provided evidence that they improve flexibility, strength, and balance; to reduce stress and conditions related to it; and specifically to alleviate some diseases such as asthma[3][4] and diabetes.[5]

Asanas have appeared in culture for many centuries. Religious Indian art depicts figures of the Buddha, Jain tirthankaras, and Shiva in lotus position and other meditation seats, and in the "royal ease" position, lalitasana. With the popularity of yoga as exercise, asanas feature commonly in novels and films, and sometimes also in advertising.

History

[edit]Ancient times

[edit]

The central figure in the Pashupati seal from the Indus Valley Civilization of c. 2500 BC was identified by Sir John Marshall in 1931 as a prototype of the god Shiva, recognised by being three-faced; in a yoga position as the Mahayogin, the god of yoga; having four animals as Pashupati, the Lord of Beasts; with deer beneath the throne, as in medieval depictions of Shiva; having a three-part headdress recalling Shiva's trident; and possibly being ithyphallic, again like Shiva.[6] If correct, this would be the oldest record of an asana. However, with no proof anywhere of an Indus Valley origin for Shiva, with multiple competing interpretations of the Pashupati seal and no obvious way of deciding between these, there is no reliable evidence that it is actually a yoga pose that is depicted in the seal.[7][8][9][10][11]

Asanas originated in India. In his Yoga Sutras, Patanjali (c. 2nd to 4th century CE) describes asana practice as the third of the eight limbs (Sanskrit: अष्टाङ्ग, aṣṭāṅga, from अष्ट् aṣṭ, eight, and अङ्ग aṅga, limb) of classical, or raja yoga.[12] The word asana, in use in English since the 19th century, is from Sanskrit: आसन āsana "sitting down" (from आस् ās "to sit down"), a sitting posture, a meditation seat.[13][14]

The eight limbs are, in order, the yamas (codes of social conduct), niyamas (self-observances), asanas (postures), pranayama (breath work), pratyahara (sense withdrawal or non-attachment), dharana (concentration), dhyana (meditation), and samadhi (realization of the true Self or Atman, and unity with Brahman, ultimate reality).[15] Asanas, along with the breathing exercises of pranayama, are the physical movements of hatha yoga and of modern yoga.[16][17] Patanjali describes asanas as a "steady and comfortable posture",[18] referring to the seated postures used for pranayama and for meditation, where meditation is the path to samadhi, transpersonal self-realization.[19][20]

The Yoga Sutras do not mention a single asana by name, merely specifying the characteristics of a good asana:[21]

स्थिरसुखमासनम् ॥४६॥

sthira sukham āsanam

Asana means a steady and comfortable posture. Yoga Sutras 2:46

The Sutras are embedded in the Bhasya commentary, which scholars suggest may also be by Patanjali;[22] it names 12 seated meditation asanas including Padmasana, Virasana, Bhadrasana, and Svastikasana.[23]

Medieval texts

[edit]The 10th–11th century Vimanarcanakalpa is the first manuscript to describe a non-seated asana, in the form of Mayurasana (peacock) – a balancing pose. Such poses appear, according to the scholar James Mallinson, to have been created outside Shaivism, the home of the Nath yoga tradition, and to have been associated with asceticism; they were later adopted by the Nath yogins.[24][25]

The Goraksha Sataka (10–11th century), or Goraksha Paddhathi, an early hatha yogic text, describes the origin of the 84 classic asanas said to have been revealed by the Hindu deity Lord Shiva.[26] Observing that there are as many postures as there are beings and asserting that there are 84 lakh[b] or 8,400,000[27] species in all, the text states that Lord Shiva fashioned an asana for each lakh, thus giving 84 in all, although it mentions and describes only two in detail: Siddhasana and Padmasana.[26] The number 84 is symbolic rather than literal, indicating completeness and sacredness.[c][28]

The Hatha Yoga Pradipika (15th century) specifies that of these 84, the first four are important, namely the seated poses Siddhasana, Padmasana, Bhadrasana and Simhasana.[30]

The pillars of the 16th century Achyutaraya temple at Hampi are decorated with numerous relief statues of yogins in asanas including Siddhasana balanced on a stick, Chakrasana, Yogapattasana which requires the use of a strap, and a hand-standing inverted pose with a stick, as well as several unidentified poses.[31]

By the 17th century, asanas became an important component of Hatha yoga practice, and more non-seated poses appear.[32] The Hatha Ratnavali by Srinivasa (17th century)[33][34] is one of the few texts to attempt an actual listing of 84 asanas,[e] although 4 out of its list cannot be translated from the Sanskrit, and at least 11[f] are merely mentioned without any description, their appearance known from other texts.[34]

The Gheranda Samhita (late 17th century) again asserts that Shiva taught 84 lakh of asanas, out of which 84 are preeminent, and "32 are useful in the world of mortals."[g][35] The yoga teacher and scholar Mark Singleton notes from study of the primary texts that "asana was rarely, if ever, the primary feature of the significant yoga traditions in India."[36] The scholar Norman Sjoman comments that a continuous tradition running all the way back to the medieval yoga texts cannot be traced, either in the practice of asanas or in a history of scholarship.[37]

Modern pioneers

[edit]

From the 1850s onwards, a culture of physical exercise developed in India to counter the colonial stereotype of supposed "degeneracy" of Indians compared to the British,[40][41] a belief reinforced by then-current ideas of Lamarckism and eugenics.[42][43] This culture was taken up from the 1880s to the early 20th century by Indian nationalists such as Tiruka, who taught exercises and unarmed combat techniques under the guise of yoga.[44][45] Meanwhile, proponents of Indian physical culture like K. V. Iyer consciously combined "hata yoga" [sic] with bodybuilding in his Bangalore gymnasium.[46][47]

Singleton notes that poses close to Parighasana, Parsvottanasana, Navasana and others were described in Niels Bukh's 1924 Danish text Grundgymnastik eller primitiv gymnastik[38] (known in English as Primary Gymnastics).[36] These in turn were derived from a 19th-century Scandinavian tradition of gymnastics dating back to Pehr Ling, and "found their way to India" by the early 20th century.[36][48]

Yoga asanas were brought to America in 1919 by Yogendra, sometimes called "the Father of the Modern Yoga Renaissance", his system influenced by the physical culture of Max Müller.[49]

In 1924, Swami Kuvalayananda founded the Kaivalyadhama Health and Yoga Research Center in Maharashtra.[50] He combined asanas with Indian systems of exercise and modern European gymnastics, having according to the scholar Joseph Alter a "profound" effect on the evolution of yoga.[51]

In 1925, Paramahansa Yogananda, having moved from India to America, set up the Self-Realization Fellowship in Los Angeles, and taught yoga, including asanas, breathing, chanting and meditation, to tens of thousands of Americans, as described in his 1946 Autobiography of a Yogi.[52][53]

Tirumalai Krishnamacharya (1888–1989) studied under Kuvalayananda in the 1930s, creating "a marriage of hatha yoga, wrestling exercises, and modern Western gymnastic movement, and unlike anything seen before in the yoga tradition."[36] Sjoman argues that Krishnamacharya drew on the Vyayama Dipika[54] gymnastic exercise manual to create the Mysore Palace system of yoga.[55] Singleton argues that Krishnamacharya was familiar with the gymnastics culture of his time, which was influenced by Scandinavian gymnastics; his experimentation with asanas and innovative use of gymnastic jumping between poses may well explain, Singleton suggests, the resemblances between modern standing asanas and Scandinavian gymnastics.[36] Krishnamacharya, known as the father of modern yoga, had among his pupils people who became influential yoga teachers themselves: the Russian Eugenie V. Peterson, known as Indra Devi; Pattabhi Jois, who founded Ashtanga (vinyasa) yoga in 1948; B.K.S. Iyengar, his brother-in-law, who founded Iyengar Yoga; T.K.V. Desikachar, his son, who continued his Viniyoga tradition; Srivatsa Ramaswami; and A. G. Mohan, co-founder of Svastha Yoga & Ayurveda.[56][57] Together they revived the popularity of yoga and brought it to the Western world.[58][59]

In 1960, Vishnudevananda Saraswati, in the Sivananda yoga school, published a compilation of sixty-six basic postures and 136 variations of those postures in The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga.[60]

In 1966, Iyengar published Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika, illustrated with some 600 photographs of Iyengar demonstrating around 200 asanas; it systematised the physical practice of asanas. It became a bestseller, selling three million copies, and was translated into some 17 languages.[61]

In 1984, Dharma Mittra compiled a list of about 1,300 asanas and their variations, derived from ancient and modern sources, illustrating them with photographs of himself in each posture; the Dharma Yoga website suggests that he created some 300 of these.[62][63][64]

Origins of the asanas

[edit]

The asanas have been created at different times, a few being ancient, some being medieval, and a growing number recent.[65][66][67] Some that appear traditional, such as Virabhadrasana I (Warrior Pose I), are relatively recent: that pose was probably devised by Krishnamacharya around 1940, and it was popularised by his pupil, Iyengar.[68] A pose that is certainly younger than that is Parivritta Parsvakonasana (Revolved Side Angle Pose): it was not in the first edition of Pattabhi Jois's Yoga Mala in 1962.[69] Viparita Virabhadrasana (Reversed Warrior Pose) is still more recent, and may have been created after 2000.[69] Several poses that are now commonly practised, such as Dog Pose and standing asanas including Trikonasana (triangle pose), first appeared in the 20th century,[70] as did the sequence of asanas, Surya Namaskar (Salute to the Sun). A different sun salutation, the Aditya Hridayam, is certainly ancient, as it is described in the "Yuddha Kaanda" Canto 107 of the Ramayana.[71] Surya Namaskar in its modern form was created by the Raja of Aundh, Bhawanrao Shriniwasrao Pant Pratinidhi;[72][73][74] K. Pattabhi Jois defined the variant forms Surya Namaskar A and B for Ashtanga Yoga, possibly derived from Krishnamacharya.[75] Surya Namaskar can be seen as "a modern, physical culture-oriented rendition" of the simple ancient practice of prostrating oneself to the sun.[76]

In 1966, Iyengar's classic Light on Yoga was able to describe some 200 asanas,[77] consisting of about 50 main poses with their variations.[78] Sjoman observes that whereas many traditional asanas are named for objects (like Vrikshasana, tree pose), legendary figures (like Matsyendrasana, the sage Matsyendra's pose), or animals (like Kurmasana, tortoise pose), "an overwhelming eighty-three"[78] of Iyengar's asanas have names that simply describe the body's position (like Utthita Parsvakonasana, "Extended Side Angle Pose"); these are, he suggests, the ones "that have been developed later".[78] A name following this pattern is Shatkonasana, "Six Triangles Pose", described in 2015.[79] Mittra illustrated 908 poses and variations in his 1984 Master Yoga Chart, and many more have been created since then.[77][79] The number of asanas has thus grown increasingly rapidly with time, as summarised in the table.

Sjoman notes that the names of asanas have been used "promiscuous[ly]", in a tradition of "amalgamation and borrowing" over the centuries, making their history difficult to trace.[80] The presence of matching names is not proof of continuity, since the same name may mean a different pose, and a pose may have been known by multiple names at different times.[80] The estimates here are therefore based on actual descriptions of the asanas.

| No. of asanas | Sanskrit | Transliteration | English | Author | Date | Evidence supplied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | गोरक्ष शतक | Goraksha Shataka | Goraksha's Century | Gorakshanatha | 10th-11th century | Describes Siddhasana, Padmasana;[81][82] 84 claimed[c] |

| 4 | शिव संहिता | Shiva Samhita | Shiva's Compendium | - | 15th century | 4 seated asanas described, 84 claimed; 11 mudras[83] |

| 15 | हठ योग प्रदीपिका | Hatha Yoga Pradipika | A Small Light on Hatha Yoga | Svami Svatmarama | 15th century | 15 asanas described,[83] 4 (Siddhasana, Padmasana, Bhadrasana and Simhasana) named as important[30] |

| 32 | घेरंड संहिता | Gheranda Samhita | Gheranda's Collection | Gheranda | 17th century | Descriptions of 32 seated, backbend, twist, balancing and inverted asanas, 25 mudras[35][83] |

| 52 | हठ रत्नावली | Hatha Ratnavali | A Treatise On Hatha Yoga | Srinivasa | 17th century | 52 asanas described, out of 84 named[h][33][34] |

| 84 | जोग प्रदीपिका | Joga Pradipika | A Small Light on Yoga | Ramanandi Jayatarama | 1830 | 84 asanas and 24 mudras in rare illustrated edition of 18th century text[84] |

| 37 | योग सोपान | Yoga Sopana | Stairway to Yoga | Yogi Ghamande | 1905 | Describes and illustrates 37 asanas, 6 mudras, 5 bandhas[84] |

| c. 200 | योग दीपिका | Yoga Dipika | Light on Yoga | B. K. S. Iyengar | 1966 | Descriptions and photographs of each asana[85] |

| 908 | — | — | Master Yoga Chart | Dharma Mittra | 1984 | Photographs of each asana[86] |

The graph shows the rapid growth in number of asanas in the 20th century.

Purposes

[edit]Spiritual

[edit]

The asanas of hatha yoga originally had a spiritual purpose within Hinduism, the attainment of samadhi, a state of meditative consciousness.[87] The scholar of religion Andrea Jain notes that medieval Hatha Yoga was shared among yoga traditions, from Shaivite Naths to Vaishnavas, Jains and Sufis; in her view, its aims too varied, including spiritual goals involving the "tantric manipulation of the subtle body", and at a more physical level, destroying poisons.[88] Singleton describes Hatha Yoga's purpose as "the transmutation of the human body into a vessel immune from mortal decay", citing the Gheranda Samhita's metaphor of an earthenware pot that requires the fire of yoga to make it serviceable.[89] Mallinson and Singleton note that the purposes of asana practice were, until around the fourteenth century, firstly to form a stable platform for pranayama, mantra repetition (japa), and meditation, practices that in turn had spiritual goals; and secondly to stop the accumulation of karma and instead acquire ascetic power, tapas, something that conferred "supernatural abilities". Hatha Yoga added the ability to cure diseases to this list.[90] Not all Hindu scriptures agreed that asanas were beneficial. The 10th century Garuda Purana stated that "the techniques of posture do not promote yoga. Though called essentials, they all retard one's progress," while early yogis often practised extreme austerities (tapas) to overcome what they saw as the obstacle of the body in the way of liberation.[91]

The yoga scholar and practitioner Theos Bernard, in his 1944 Hatha Yoga: The Report of a Personal Experience, stated that he was "prescribed ... a group of asanas[i] calculated to bring a rich supply of blood to the brain and to various parts of the spinal cord .. [and] a series of reconditioning asanas to stretch, bend, and twist the spinal cord" followed when he was strong enough by the meditation asanas.[93] Bernard named the purpose of Hatha Yoga as "to gain control of the breath" to enable pranayama to work, something that in his view required thorough use of the six purifications.[94]

Asanas work in different ways from conventional physical exercises, according to Satyananda Saraswati "placing the physical body in positions that cultivate awareness, relaxation and concentration".[95] Leslie Kaminoff writes in Yoga Anatomy that from one point of view, "all of asana practice can be viewed as a methodical way of freeing up the spine, limbs, and breathing so that the yogi can spend extended periods of time in a seated position."[96]

Iyengar observed that the practice of asanas "brings steadiness, health, and lightness of limb. A steady and pleasant posture produces mental equilibrium and prevents fickleness of mind." He adds that they bring agility, balance, endurance, and "great vitality", developing the body to a "fine physique which is strong and elastic without being muscle-bound". But, Iyengar states, their real importance is the way they train the mind, "conquer[ing]" the body and making it "a fit vehicle for the spirit".[97]

| Asana | Level |

|---|---|

| Vishnu's Couch, Salute to the Sun |

Gods |

| Virabhadra, Matsyendra |

Heroes, sages |

| Dog | Mammals |

| Pigeon | Birds |

| Cobra | Reptiles |

| Fish, Frog |

Aquatic animals |

| Locust | Invertebrates |

| Tree | Plants |

| Mountain | Inanimate |

Iyengar saw it as significant that asanas are named after plants, insects, fish and amphibians, reptiles, birds, and quadrupeds; as well as "legendary heroes", sages, and avatars of Hindu gods, in his view "illustrating spiritual evolution".[98] For instance, the lion pose, Simhasana, recalls the myth of Narasimha, half man, half lion, and an avatar of Vishnu, as told in the Bhagavata Purana.[99] The message is, Iyengar explains, that while performing asanas, the yogi takes the form of different creatures, from the lowest to the highest, not despising any "for he knows that throughout the whole gamut of creation ... there breathes the same Universal Spirit." Through mastery of the asanas, Iyengar states, dualities like gain and loss, or fame and shame disappear.[98]

Sjoman argues that the concept of stretching in yoga can be looked at through one of Patanjali's Yoga Sutras, 2.47, which says that [asanas are achieved] by loosening (śaithilya) the effort (prayatna) and meditating on the endless (ananta). Sjoman points out that this physical loosening is to do with the mind's letting go of restrictions, allowing the natural state of "unhindered perfect balance" to emerge; he notes that one can only relax through effort, "as only a muscle that is worked is able to relax (that is, there is a distinction between dormancy and relaxation)."[100] Thus asanas had a spiritual purpose, serving to explore the conscious and unconscious mind.[101]

Heinz Grill considers the soul in our human existence to be a central link between the manifest body and the unmanifest spirit. Therefore it should not be the sense-attached, bodily-involved consciousness that motivates yoga practice, but spiritual thoughts. According to Grill, this path from above to below is essential, because “the soul lives in the receptivity of giving and not in the receptivity of earthly taking.”[102]

Exercise

[edit]Since the mid-20th century, asanas have been used, especially in the Western world, as physical exercise.[103] In this context, their "overtly Hindu" purpose is masked but its "ecstatic ... transcendent ... possibly subversive" elements remain.[104] That context has led to a division of opinion among Christians, some asserting that it is acceptable as long as they are aware of yoga's origins, others stating that hatha yoga's purpose is inherently Hindu, making Christian yoga an evident contradiction[105][106] or indeed "diametrically opposed to Christianity".[107] A similar debate has taken place in a Muslim context; under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, yoga, formerly banned as a Hindu practice, has been legalised in Saudi Arabia,[108] while mainly-Hindu Bali has held a yoga competition in defiance of a ruling by Indonesia's Muslim Ulema Council.[109]

In a secular context, the journalists Nell Frizzell and Reni Eddo-Lodge have debated (in The Guardian) whether Western yoga classes represent "cultural appropriation". In Frizzell's view, yoga has become a new entity, a long way from the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, and while some practitioners are culturally insensitive, others treat it with more respect. Eddo-Lodge agrees that Western yoga is far from Patanjali, but argues that the changes cannot be undone, whether people use it "as a holier-than-thou tool, as a tactic to balance out excessive drug use, or practised similarly to its origins with the spirituality that comes with it".[110]

From a Hindu perspective, the practice of asanas in the Western world as physical exercise is sometimes seen as yoga that has lost its way. In 2012, the Hindu American Foundation ran a "Take Back Yoga" campaign to emphasise yoga's roots in Hinduism.[111]

For women

[edit]

In the West, yoga is practiced mainly by women. For example, in Britain in the 1970s, women formed between 70 and 90 percent of most yoga classes, as well as most of the yoga teachers. It has been suggested that yoga was seen as a support for women in the face of male-dominated medicine, offering an alternative approach for chronic medical conditions, as well as to beauty and ageing, and it offered a way of meeting other women.[113] Singleton notes that women in yoga are in the tradition of Mollie Bagot Stack's 1930 League of Health and Beauty, influenced by Stack's visit to India in 1912 when she learnt some asanas, and in turn of Genevieve Stebbins's Harmonic Gymnastics.[112]

Effects

[edit]Asanas have, or are claimed to have, multiple effects on the body, both beneficial and harmful. These include the conscious usage of groups of muscles,[114] effects on health,[115] and possible injury especially in the presence of known contraindications.[116]

Muscle usage

[edit]A 2014 study indicated that different asanas activated particular groups of muscles, varying with the skill of the practitioners, from beginner to instructor. The eleven asanas in the Surya Namaskar sequences A and B (of Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga) were performed by beginners, advanced practitioners and instructors. The activation of 14 groups of muscles was measured with electrodes on the skin over the muscles. Among the findings, beginners used pectoral muscles more than instructors, whereas instructors used deltoid muscles more than other practitioners, as well as the vastus medialis (which stabilises the knee). The yoga instructor Grace Bullock writes that such patterns of activation suggest that asana practice increases awareness of the body and the patterns in which muscles are engaged, making exercise more beneficial and safer.[114][117]

Claimed benefits

[edit]Medieval hatha yoga texts make a variety of claims for the benefits brought by the asanas, both spiritual and physical. The Hatha Yoga Pradipika (HYP) states that asanas in general, described as the first auxiliary of hatha yoga, give "steadiness, good health, and lightness of limb." (HYP 1.17)[118] Specific asanas, it claims, bring additional benefits; for example, Matsyendrasana awakens Kundalini and makes the semen steady; (HYP 1.27) Paschimottanasana "stokes up the digestive fire, slims the belly and gives good health"; (HYP 1.29) Shavasana "takes away fatigue and relaxes the mind"; (HYP 1.32) Siddhasana "bursts open the door to liberation"; (HYP 1.35) while Padmasana "destroys all diseases" (HYP 1.47) and if done together with retention of the breath in pranayama confers liberation. (HYP 1.44–49)[119] These claims lie within a tradition across all forms of yoga that practitioners can gain supernatural powers, but with ambivalence about their usefulness, since they may obstruct progress towards liberation.[120] Hemachandra's Yogashastra (1.8–9) lists the magical powers, which include healing, the destruction of poisons, the ability to become as small as an atom or to go wherever one wishes, invisibility, and shape-shifting.[121]

The asanas have been popularised in the Western world by claims about their health benefits, attained not by medieval hatha yoga magic but by the physical and psychological effects of exercise and stretching on the body.[122] The history of such claims was reviewed by William J. Broad in his 2012 book The Science of Yoga. Broad argues that while the health claims for yoga began as Hindu nationalist posturing, it turns out that there is ironically[115] "a wealth of real benefits".[115]

Physically, the practice of asanas has been claimed to improve flexibility, strength, and balance; to alleviate stress and anxiety, and to reduce the symptoms of lower back pain.[3][4] Claims have been made about beneficial effects on specific conditions such as asthma,[3][4] chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,[3][4] and diabetes.[5] There is evidence that practice of asanas improves birth outcomes[4] and physical health and quality of life measures in the elderly,[4] and reduces sleep disturbances[3] and hypertension.[123][124] Iyengar yoga is effective at least in the short term for both neck pain and low back pain.[125]

Contra-indications

[edit]The National Institutes of Health notes that yoga is generally safe "when performed properly", though people with some health conditions, older people, and pregnant woman may need to seek advice. For example, people with glaucoma are advised not to practise inverted postures.[126] The Yoga Journal provides separate lists of asanas that it states are "inadvisable" and should be avoided or modified for each of the following medical conditions: asthma; back injury; carpal tunnel syndrome; diarrhoea; headache; heart problems; high blood pressure; insomnia; knee injury; low blood pressure; menstruation; neck injury; pregnancy; and shoulder injury.[116]

The practice of asanas has sometimes been advised against during pregnancy, but that advice has been contested by a 2015 study which found no ill-effects from any of 26 asanas investigated. The study examined the effects of the set of asanas on 25 healthy women who were between 35 and 37 weeks pregnant. The authors noted that apart from their experimental findings, they had been unable to find any scientific evidence that supported the previously published concerns, and that on the contrary there was evidence including from systematic review that yoga was suitable for pregnant women, with a variety of possible benefits.[127][128]

Common practices

[edit]

In the Yoga Sutras, the only rule Patanjali suggests for practicing asana is that it be "steady and comfortable".[2] The body is held poised with the practitioner experiencing no discomfort. When control of the body is mastered, practitioners are believed to free themselves from dualities such as heat and cold, hunger and satiety, or joy and grief.[129] This is the first step toward relieving suffering by letting go of attachment.[130]

Traditional and modern guidance

[edit]Different schools of yoga, such as Iyengar and The Yoga Institute, agree that asanas are best practised with a rested body on an empty stomach, after having a bath.[131][132] From the point of view of sports medicine, asanas function as active stretches, helping to protect muscles from injury; these need to be performed equally on both sides, the stronger side first if used for physical rehabilitation.[133]

Surya Namaskar

[edit]

Surya Namaskar, the Salute to the Sun, commonly practiced in most forms of modern yoga, links up to twelve asanas in a dynamically expressed yoga series. A full round consists of two sets of the series, the second set moving the opposing leg first. The asanas include Adho Mukha Svanasana (downward dog), the others differing from tradition to tradition with for instance a choice of Urdhva Mukha Svanasana (upward dog) or Bhujangasana (cobra) for one pose in the sequence.[135] Schools, too, differ in their approaches to the sequence; for example, in Iyengar Yoga, variations such as inserting Maricyasana I and Pascimottanasana are suggested.[136]

Styles

[edit]In the Western world, asanas are taught in differing styles by the various schools of yoga. Some poses like Trikonasana are common to many of them, but not always performed in the same way. Some independently documented approaches are described below.[137][138]

Iyengar Yoga "emphasises precision and alignment",[139] and prioritises correct movement over quantity, i.e. moving a little in the right direction is preferred to moving more but in a wrong direction. Postures are held for a relatively long period compared to other schools of yoga; this allows the muscles to relax and lengthen, and encourages awareness in the pose. Props including belts, blocks and blankets are freely used to assist students in correct working in the asanas.[139][138] Beginners are introduced early on to standing poses, executed with careful attention to detail. For example, in Trikonasana, the feet are often jumped apart to a wide stance, the forward foot is turned out, and the centre of the forward heel is exactly aligned with the centre of the arch of the other foot.[137]

Sivananda Yoga practices the asanas, hatha yoga, as part of raja yoga, with the goal of enabling practitioners ""to sit in meditation for a long time".[137] There is little emphasis on the detail of individual poses; teachers rely on the basic instructions given in the books by Sivananda and Swami Vishnu-devananda.[137] In Trikonasana, the top arm may be stretched forward parallel to the floor rather than straight up.[137] Sivananda Yoga identifies a group of 12 asanas as basic.[140] These are not necessarily the easiest poses, nor those that every class would include.[141] Trikonasana is the last of the 12, whereas in other schools it is one of the first and used to loosen the hips in preparation for other poses.[137]

In Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga, poses are executed differently from Iyengar Yoga. "Vinyasa" means flowing, and the poses are executed relatively rapidly, flowing continuously from one asana to the next using defined transitional movements.[137][138] The asanas are grouped into six series, one Primary, one Intermediate, and four Advanced. Practice begins and ends with the chanting of mantras, followed by multiple cycles of the Sun Salutation, which "forms the foundation of Ashtanga Yoga practice", and then one of the series.[142][143] Ashtanga Vinyasa practice emphasises aspects of yoga other than asanas, including drishti (focus points), bandhas (energy locks), and pranayama.[137]

Kripalu Yoga uses teachers from other asana traditions, focussing on mindfulness rather than using effort in the poses. Teachers may say "allow your arms to float up" rather than "bring up your arms".[137] The goal is to use the asanas "as a path of transformation."[137] The approach is in three stages: firstly instruction in body alignment and awareness of the breath during the pose; secondly, holding the pose long enough to observe "unconscious patterns of tension in the body-mind";[137] and thirdly, through "deep concentration and total surrender", allowing oneself "to be moved by prana".[137] In Trikonasana, the teacher may direct pupils' attention to pressing down with the outer edge of the back foot, lifting the arch of the foot, and then experimenting with "micro-movements", exploring where energy moves and how it feels.[137]

In Bikram Yoga, as developed by Bikram Choudhury, there is a fixed sequence of 26 poses,[138] in which Trikonasana is ninth, its task to focus on opening the hips. The Bikram version of Trikonasana is a different pose (Parsvakonasana) from that in Iyengar Yoga.[137] The position of the feet is seen as critically important, along with proper breathing and the distribution of weight: about 30% on the back foot, 70% on the front foot.[137]

Apart from the brands, many independent teachers, for example in Britain, offer an unbranded "hatha yoga".[112]

Types

[edit]Asanas can be classified in different ways, which may overlap: for example, by the position of the head and feet (standing, sitting, reclining, inverted), by whether balancing is required, or by the effect on the spine (forward bend, backbend, twist), giving a set of asana types agreed by most authors.[144][145][146] Mittra uses his own categories such as "Floor & Supine Poses".[62] Darren Rhodes and others add "Core strength",[147][148][149] while Yogapedia and Yoga Journal also add "Hip-opening" to that set.[150][151] The table shows an example of each of these types of asana, with the title and approximate date of the earliest document describing (not only naming) that asana.

- GS = Goraksha Sataka, 10th century

- HY = Hemacandra's Yogasastra, 11th century

- VS = Vasishtha Samhita, 13th century

- HYP = Hatha Yoga Pradipika, 15th century

- JP = Joga Pradipika, 18th century

- ST = Sritattvanidhi, 19th century

- TK = Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, 20th century

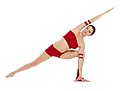

| Type | Described | Date | Example | English | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standing | TK | 20th C. | Parsvakonasana | Side angle |  |

| Sitting Meditation |

GS 1:10–12 | 10th–11th C. | Siddhasana | Accomplished |  |

| Reclining | HYP 1:34 | 15th C. | Shavasana | Corpse | |

| Inverted | HY | 11th C. | Sirsasana | Yoga headstand |

|

| Balancing | VS | 13th C. | Kukkutasana | Cockerel |  |

| Forward bend | HYP 1:30 | 15th C. | Paschimottanasana | Seated Forward Bend | |

| Backbend | HYP 1:27 | 15th C. | Dhanurasana | Bow |  |

| Twisting | HYP 1.28–29 | 15th C. | Ardha Matsyendrasana |

Half Lord of the Fishes |

|

| Hip-opening | HYP 1:20 | 15th C. | Gomukhasana | Cow Face |  |

| Core strength | ST | 19th C. | Navasana | Boat |  |

In culture

[edit]In religious art

[edit]

Religious Indian art makes use of a variety of seated asanas for figures of Buddha, Shiva, and other gods and religious figures. Most are meditation seats, especially the lotus position, Padmasana, but Lalitasana and its "royal ease" variant are not.[152][153] Jain tirthankaras are often shown seated in the meditation asanas Siddhasana and Padmasana.[154][155]

In literature

[edit]The actress Mariel Hemingway's 2002 autobiography Finding My Balance: A Memoir with Yoga describes how she used yoga to recover balance in her life after a dysfunctional upbringing: among other things, her grandfather, the novelist Ernest Hemingway, killed himself shortly before she was born, and her sister Margaux killed herself with a drug overdose. Each chapter is titled after an asana, the first being "Mountain Pose, or Tadasana", the posture of standing in balance. Other chapters are titled after poses including Trikonasana, Virabhadrasana, Janusirsasana, Ustrasana, Sarvangasana, and finally Garudasana, in each case with some life lesson related to the pose. For example, Garudasana, "a balancing posture with the arms and legs intricately intertwined ... requires some flexibility, a lot of trust, and most of all, balance"; the chapter recounts how she, her husband and her daughters all came close to drowning in canoes off Kauai, Hawaii.[156][157]

Among yoga novels is the author and yoga teacher Edward Vilga's 2014 Downward Dog, named for Adho Mukha Svanasana, which paints a humorously unflattering picture of a man of the world who decides to become a private yoga teacher in New York society.[158][159] Ian Fleming's 1964 novel You Only Live Twice has the action hero James Bond visiting Japan, where he "assiduously practised sitting in the lotus position."[160] The critic Lisa M. Dresner notes that Bond is mirroring Fleming's own struggles with the pose.[161]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Paśupati, "Lord of beasts", is a name of the later Hindu god Shiva.

- ^ A lakh is 100,000

- ^ a b 84's symbolism may derive from its astrological and numerological properties: it is the product of 7, the number of planets in astrology, and 12, the number of signs of the zodiac, while in numerology, 7 is the sum of 3 and 4, and 12 is the product, i.e. 84 is (3+4)×(3×4).[28]

- ^ The posture has the left arm supporting the body and the left leg behind the neck, as in Chakorasana, and Omkarasana, but with the right arm bent, not supporting the body.

- ^ The Hatha Ratnavali's list of 84 asanas is

- "Siddhasana, Bhadrasana, Vajrasana, Simhasana, Silpasana,

- four types of Padmasana, such as Bandha, Kara, Samputita and Suddha;

- six types of Mayurasana such as Danda, Parsva, Sahaja, Bandha, Pinda, Ekapada;

- Bhairavasana, Kamadahana, Panipatra, Karmuka, Svastikasana, Gomukhasana, Virasana, Mandukasana, Markata, Matsyendrasana, Parsvamatsyendrasana, Baddhamatsyendrasana, Niralambanasana, Candrasana, Kanthava, Ekapadaka, Phanindra, Pascimottanasana, Sayitapascimatana, Citrakarani, Yoganidrasana, Vidhunana, Padapidana, Hamsa, Nabhitala, Akasa, Utpadatala, Nabhllasitapadaka, Vrischikasana, Cakrasana, Utphalaka, Uttanakurma, Kurmasana, Baddhakurma, Narjava, Kabandha, Gorakshasana, Angusthasana, Mustika, Brahmaprasadita;

- five Kukkutas such as Pahcaculikukkuta, Ekapadakakukkuta, Akarita, Bandhacull and Parsvakukkuta;

- Ardhanarisvara, Bakasana, Dharavaha, Candrakanta, Sudhasara, Vyaghrasana, Rajasana, Indrani, Sarabhasana, Ratnasana, Citrapitha, Baddhapaksi, Isvarasana, Vicitranalina, Kanta, Suddhapaksi, Sumandraka, Caurangi, Krauncasana, Drdhasana, Khagasana, Brahmasana, Nagapitha and lastly Savasana."

- ^ The 11 are Karmukasana, Hamsasana, Cakrasana, Kurmasana, Citrapitha, Goraksasana, Angusthasana, Vyaghrasana, Sara(la)bhasana, Krauncasana, Drdhasana.

- ^ The 32 "useful" asanas of the Gheranda Samhita are: Siddhasana, Padmasana, Bhadrasana, Muktasana, Vajrasana, Svastikasana, Simhasana, Gomukhasana, Virasana, Dhanurasana, Mritasana, Guptasana, Matsyasana, Matsyendrasana, Gorakshanasana, Paschimottanasana, Utkatasana, Sankatasana, Mayurasana, Kukkutasana, Kurmasana, Uttanakurmakasana, Uttana Mandukasana, Vrikshasana, Mandukasana, Garudasana, Vrishasana, Shalabhasana, Makarasana, Ushtrasana, Bhujangasana, and Yogasana.[35]

- ^ 84 names of asanas are listed; not all can now be identified.

- ^ Bernard's book contains 37 photographs of himself performing asanas and mudras.[92]

References

[edit]- ^ Verse 46, chapter II, "Patanjali Yoga sutras" by Swami Prabhavananda, published by the Sri Ramakrishna Math ISBN 978-81-7120-221-8 p. 111

- ^ a b c Patanjali Yoga sutras, Book II:29, 46

- ^ a b c d e Ross, A.; Thomas, S. (January 2010). "The health benefits of yoga and exercise: a review of comparison studies". Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 16 (1): 3–12. doi:10.1089/acm.2009.0044. PMID 20105062. S2CID 14130906.

- ^ a b c d e f Hayes, M.; Chase, S. (March 2010). "Prescribing Yoga". Primary Care. 37 (1): 31–47. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2009.09.009. PMID 20188996.

- ^ a b Alexander G. K.; Taylor, A. G.; Innes, K. E.; Kulbok, P.; Selfe, T. K. (2008). "Contextualizing the effects of yoga therapy on diabetes management: a review of the social determinants of physical activity". Fam Community Health. 31 (3): 228–239. doi:10.1097/01.FCH.0000324480.40459.20. PMC 2720829. PMID 18552604.

- ^ McEvilley 1981.

- ^ Singleton 2010, p. 25.

- ^ Doniger 2011, pp. 485–508.

- ^ Samuel 2017, p. 8.

- ^ Shearer 2020, p. 18.

- ^ Srinivasan 1984, pp. 77–89.

- ^ Feuerstein, Georg; Wilber, Ken (2002). "The Wheel of Yoga". The Yoga Tradition. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. pp. 108ff. ISBN 978-81-208-1923-8.

- ^ Monier-Williams, Monier (1899). "Asana". A Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Oxford Clarendon Press. p. 159.

- ^ "Asana". Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ Humphrey, Naomi (1987). Meditation: The Inner Way. HarperCollins (Aquarian Press). pp. 112–113. ISBN 0-85030-508-X.

- ^ Markil, Nina; Geithner, Christina A.; Penhollow, Tina M. (2010). "Hatha Yoga". ACSM's Health & Fitness Journal. 14 (5): 19–24. doi:10.1249/fit.0b013e3181ed5af2. S2CID 78930751.

- ^ Joshi, K. S. (January 1965). "On the Meaning of Yoga". Philosophy East and West. 15 (1): 53–64. doi:10.2307/1397408. JSTOR 1397408.

Hatha-yoga purports, through physical postures and breathing exercises, to bring about a psycho-physiologically integrative adjustment of human behavior.

- ^ Patanjali. Yoga Sutras. p. 2.47.

- ^ Patañjali; Āraṇya, Hariharānanda (trans.) (1983). Yoga philosophy of Patañjali: containing his Yoga aphorisms with Vyasa's commentary in Sanskrit and a translation with annotations including many suggestions for the practice of Yoga. State University of New York Press. pp. 252–253. ISBN 978-0-87395-728-1. OCLC 9622445.

- ^ Desmarais, Michele Marie (2008). Changing Minds : Mind, Consciousness and Identity in Patanjali's Yoga-Sutra. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-8120833364.

- ^ Patanjali. Yoga Sutras. p. Book 2:46.

- ^ Maas, Philipp A. (2006). Samādhipāda. Das erste Kapitel des Pātañjalayogaśāstra zum ersten Mal kritisch ediert [Samādhipāda: The First Chapter of the Pātañjalayogaśāstra for the First Time Critically Edited] (in German). Aachen: Shaker.

- ^ Āraṇya, Hariharānanda (1983). Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali. State University of New York Press. p. 228 and footnotes. ISBN 978-0873957281.

- ^ Mallinson, James (9 December 2011). "A Response to Mark Singleton's Yoga Body by James Mallinson". Retrieved 4 January 2019. revised from American Academy of Religions conference, San Francisco, 19 November 2011.

- ^ Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 100–101.

- ^ a b Goraksha-Paddhati. Archived from the original on 2011-09-03. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ Singh, T. D.; Hinduism and Science

- ^ a b Rosen, Richard (2017). Yoga FAQ: Almost Everything You Need to Know about Yoga-from Asanas to Yamas. Shambhala. pp. 171–. ISBN 978-0-8348-4057-7.

this number has symbolic significance. S. Dasgupta, in Obscure Religious Cults (1946), cites numerous instances of variations on eighty-four in Indian literature that stress its 'purely mystical nature'; ... Gudrun Bühnemann, in her comprehensive Eighty-Four Asanas in Yoga, notes that the number 'signifies completeness, and in some cases, sacredness. ... John Campbell Oman, in The Mystics, Ascetics, and Saints of India (1905) ... seven ... classical planets in Indian astrology ... and twelve, the number of signs of the zodiac. ... Matthew Kapstein gives .. a numerological point of view ... 3+4=7 ... 3x4=12 ...

- ^ Suresh, K. M. (1998). Sculptural Art of Hampi. Directorate of Archaeology and Museums. pp. 190–195.

- ^ a b Chapter 1, 'On Asanas', Hatha Yoga Pradipika

- ^ "Hampi". The Hatha Yoga Project | School of Oriental and Asiatic Studies. 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

This is a selection of images of yogis from 16th-century temple pillars at Hampi, Karnataka, the erstwhile Vijayanagar. The photographs were taken by Dr Mallinson and Dr Bevilacqua in March 2016.

- ^ Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 91, 114–119.

- ^ a b The Yoga Institute (Santacruz East Bombay India) (1988). Cyclopaedia Yoga. The Yoga Institute. p. 32.

- ^ a b c Mallinson, James (2004). The Gheranda Samhita: the original Sanskrit and an English translation. YogaVidya. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-0-9716466-3-6.

- ^ a b c d e Singleton, Mark (4 February 2011). "The Ancient & Modern Roots of Yoga". Yoga Journal.

- ^ Sjoman 1999, p. 40.

- ^ a b Bukh 1924.

- ^ Singleton 2010, p. 200.

- ^ Singleton 2010, pp. 95–97.

- ^ Rosselli, J. (February 1980). "The Self-Image of Effeteness: Physical Education and Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Bengal". Past & Present (86): 121–148. doi:10.1093/past/86.1.121. JSTOR 650742. PMID 11615074.

- ^ Singleton 2010, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Kevles, Daniel (1995). In the name of eugenics : genetics and the uses of human heredity. Harvard University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-674-44557-4. OCLC 32430452.

- ^ Singleton 2010, pp. 98–106.

- ^ Tiruka (Sri Raghavendra Swami) (1977). Suryanamaskara. Malladhihalli: Sarvodaya Mudranalaya, Anathasevashrama Trust. p. v. OCLC 20519100.

- ^ Singleton 2010, pp. 122–129.

- ^ Iyer, K. V. (1930). Muscle Cult: A Pro-Em to My System. Bangalore: Hercules Gymnasium and Correspondence School of Physical Culture. pp. 41–42. OCLC 37973753.

- ^ Singleton 2010, pp. 84–88.

- ^ Mishra, Debashree (3 July 2016). "Once Upon A Time: From 1918, this Yoga institute has been teaching generations, creating history". Mumbai: Indian Express.

- ^ Wathen, Grace (1 July 2011). "Kaivalyadhama & Yoga Postures". LiveStrong. Archived from the original on 12 November 2011.

- ^ Alter 2004, p. 31.

- ^ Yogananda, Paramahansa (1971) [1946]. Autobiography of a Yogi. Self-Realization Fellowship. ISBN 978-0-87612-079-8. OCLC 220261.

- ^ Singleton 2010, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Bharadwaj 1896.

- ^ Sjoman 1999, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Iyengar, B. K. S. (2006). Light on Life: The Yoga Journey to Wholeness, Inner Peace, and Ultimate Freedom. Rodale. pp. xvi–xx. ISBN 978-1-59486-524-4.

- ^ Mohan, A. G. (2010). Krishnamacharya: His Life and Teachings. Shambhala. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-59030-800-4.

- ^ Pages Ruiz, Fernando (28 August 2007). "Krishnamacharya's Legacy: Modern Yoga's Inventor". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ Singleton 2010, pp. 175–210.

- ^ Vishnu-devananda 1988.

- ^ Stukin, Stacie (10 October 2005). "Yogis gather around the guru". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ a b Mittra 2003.

- ^ "Yoga.com". Yoga.com. 27 February 2005. Archived from the original on 6 September 2010. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- ^ "About Sri Dharma Mittra". Dharma Yoga. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

Over 300 of these now-popular posture variations were created by Sri Dharma, though he will always say they only came through Divine intuition.

- ^ "What's behind the five popular yoga poses loved by the world?". BBC. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ Mallinson & Singleton 2017, p. xxix.

- ^ Singleton 2010, p. 161.

- ^ Dowdle, Hillary (11 November 2008). "5 Experts, 1 Pose: Find New Nuances to Warrior I". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ a b Kaivalya, Alanna (28 April 2012). "How We Got Here: Where Yoga Poses Come From". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

Most recently, additions like "falling star," "reverse warrior," and "flip the dog," weren't around even 10 short years ago.

- ^ Vaughn, Amy (16 December 2013). "Early History of Asana: What Were the Original Postures & Where Did They Come From?". Elephant Journal. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ "Dityahrdayam | from the Ramayana" (PDF). Safire. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

6. Worship the sun-god, the ruler of the worlds, who is crowned with rays, who appears at the horizon, who is greeted by gods and demons, and brings light.

- ^ Singleton 2010, p. 124.

- ^ Alter, Joseph S. (2000). Gandhi's Body: Sex, Diet, and the Politics of Nationalism. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-8122-3556-2.

- ^ Pratinidhi, Pant; Morgan, L. (1938). The Ten-Point Way to Health. Surya namaskars... Edited with an introduction by Louise Morgan, etc. London: J. M. Dent. OCLC 1017424915.

- ^ "The sequence of rhythmic postures: the sun salutation". Ashtanga Yoga Institute. 20 November 2014. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ Singleton 2010, pp. 205–206.

- ^ a b McCrary, Meagan (15 July 2015). "#YJ40: 10 Poses Younger Than Yoga Journal". Yoga Journal.

- ^ a b c Sjoman 1999, p. 49.

- ^ a b Lacerda, Daniel (2015). 2,100 Asanas: The Complete Yoga Poses. Running Press. pp. 1174–1175. ISBN 978-0-316-27062-5.

- ^ a b Sjoman 1999, p. 59.

- ^ Singh, T. D. (2005). "Science and Religion: Global Perspectives, 4–8 June 2005, Philadelphia | Hinduism and Science" (PDF). Metanexus Institute.

- ^ Swami Kuvalayananda; Shukla, S. A., eds. (December 2006). Goraksha Satakam. Lonavla, India: Kaivalyadhama S. M. Y. M. Samiti. pp. 37–38. ISBN 81-89485-44-X.

- ^ a b c Singleton 2010, p. 29.

- ^ a b Singleton 2010, p. 170.

- ^ Iyengar, B. K. S. (1991) [1966]. Light on Yoga. London: Thorsons. ISBN 978-0-00-714516-4. OCLC 51315708.

- ^ Mittra, Dharma (1984). Master Chart of Yoga Poses.

- ^ Mallinson, James (2011). Knut A. Jacobsen; et al. (eds.). Haṭha Yoga in the Brill Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Vol. 3. Brill Academic. pp. 770–781. ISBN 978-90-04-27128-9.

- ^ Jain 2015, pp. 13–18.

- ^ Singleton 2010, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 92–95.

- ^ Boccio, Frank Jude (3 December 2012). "21st Century Yoga: Questioning the 'Body Beautiful': Yoga, Commercialism & Discernment". Elephant Journal.

- ^ Bernard 2007, pp. 107–137.

- ^ Bernard 2007, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Bernard 2007, p. 33.

- ^ Saraswati 1996, p. 12: "Yogasanas have often been thought of as a form of exercise. They are not exercises, but techniques which place the physical body in positions that cultivate awareness, relaxation, concentration and meditation.".

- ^ Kaminoff & Matthews 2012, p. 125.

- ^ Iyengar 1979, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b c Iyengar 1979, p. 42.

- ^ Kaivalya, Alanna (2016). Myths of the Asanas: The Stories at the Heart of the Yoga Tradition. Mandala Publishing. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-68383-023-8.

- ^ Sjoman 1999, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Sjoman 1999, p. 47.

- ^ Grill, Heinz (2005). The Soul Dimension of Yoga – A practical foundation for a path of spiritual practice (1 ed.). Lammers-Koll-Verlag. pp. 13–18. ISBN 978-3-935925-57-0.

- ^ Nanda, Meera (12 February 2011). "Not as Old as You Think". OPEN Magazine.

- ^ Syman, Stefanie (2010). The Subtle Body: The Story of Yoga in America. Macmillan. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-374-23676-2.

But many of those aspects of yoga – the ecstatic, the transcendent, the overtly Hindu, the possibly subversive, and eventually the seemingly bizarre—that you wouldn't see on the White House grounds that day and that you won't find in most yoga classes persist, right here in America.

- ^ Davis, Alexandra (1 January 2016). "Should Christians do yoga? | We asked two Christians who have tried yoga to give us their thoughts". Evangelical Alliance. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ Jain, Andrea (21 June 2017). "Can yoga be Christian?". The Conversation. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ Jones, Emily (14 November 2018). "Is Yoga Evil? See Why One Megachurch Pastor Says It's 'Diametrically Opposed to Christianity'". CBN News. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ Chopra, Anuj (30 September 2018). "Saudi Arabia embraces yoga in pivot toward 'moderation'". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ Gelling, Peter (9 March 2009). "Bali Defies Fatwa on Yoga". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ Frizzell, Nell; Eddo-Lodge, Reni (23 November 2015). "Are yoga classes just bad cultural appropriation?". The Guardian.

- ^ Adler, Margot (11 April 2012). "To Some Hindus, Modern Yoga Has Lost Its Way". NPR. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ a b c Singleton 2010, pp. 150–152.

- ^ Newcombe, Suzanne (2007). "Stretching for Health and Well-Being: Yoga and Women in Britain, 1960–1980". Asian Medicine. 3 (1): 37–63. doi:10.1163/157342107X207209. S2CID 72555878.

- ^ a b Ni, Meng; Mooney, Kiersten; Balachandran, Anoop; Richards, Luca; Harriell, Kysha; Signorile, Joseph F. (2014). "Muscle utilization patterns vary by skill levels of the practitioners across specific yoga poses (asanas)". Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 22 (4): 662–669. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2014.06.006. ISSN 0965-2299. PMID 25146071.

- ^ a b c Broad, William J. (2012). The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards. Simon and Schuster. p. 39 and whole book. ISBN 978-1-4516-4142-4.

- ^ a b "Contraindications". Yoga Journal. Archived from the original on 25 November 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ Bullock, B. Grace (2016). "Which Muscles Are You Using in Your Yoga Practice? A New Study Provides the Answers". Yoga U. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ Mallinson & Singleton 2017, p. 108.

- ^ Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 108–111.

- ^ Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 359–361.

- ^ Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 385–387.

- ^ "Yoga Health Benefits: Flexibility, Strength, Posture, and More". WebMD. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ^ Silverberg, D. S. (September 1990). "Non-pharmacological treatment of hypertension". Journal of Hypertension Supplement. 8 (4): S21–26. PMID 2258779.

- ^ Labarthe, D.; Ayala, C. (May 2002). "Nondrug interventions in hypertension prevention and control". Cardiol Clin. 20 (2): 249–263. doi:10.1016/s0733-8651(01)00003-0. PMID 12119799.

- ^ Crow, Edith Meszaros; Jeannot, Emilien; Trewhela, Alison (2015). "Effectiveness of Iyengar yoga in treating spinal (back and neck) pain: A systematic review". International Journal of Yoga. 8 (1). Medknow: 3–14. doi:10.4103/0973-6131.146046. ISSN 0973-6131. PMC 4278133. PMID 25558128.

- ^ "Yoga: In Depth". National Institutes of Health. October 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ Polis, Rachael L.; Gussman, Debra; Kuo, Yen-Hong (2015). "Yoga in Pregnancy". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 126 (6): 1237–1241. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001137. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 26551176. S2CID 205467344.

All 26 yoga postures were well-tolerated with no acute adverse maternal physiologic or fetal heart rate changes.

- ^ Curtis, Kathryn; Weinrib, Aliza; Katz, Joel (2012). "Systematic Review of Yoga for Pregnant Women: Current Status and Future Directions". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012: 1–13. doi:10.1155/2012/715942. ISSN 1741-427X. PMC 3424788. PMID 22927881.

- ^ "Asana | 8 Limbs of Yoga". United We Care. July 5, 2021. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ Feuerstein, Georg (2003). The Deeper Dimensions of Yoga: Theory and Practice. Shambhala Publications. ISBN 978-1-57062-935-8.

- ^ Iyengar 1979, pp. 57–60, 63.

- ^ "Yoga Asanas Do's and Don'ts for Beginners". The Yoga Institute. 9 January 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ Srinivasan, T. M. (2016). "Dynamic and static asana practices". International Journal of Yoga. 9 (1). Medknow: 1–3. doi:10.4103/0973-6131.171724. PMC 4728952. PMID 26865764.

- ^ "Surya Namaskara A & B". Ashtanga Yoga. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Easa, Leila. "How to Salute the Sun". Yoga Journal. Archived from the original on 5 April 2010. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ Mehta, Mehta & Mehta 1990, pp. 146–147.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Jones, Todd (28 August 2007). "Illustrate Different Yoga Methods with Trikonasana". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d Beirne, Geraldine (10 January 2014). "Yoga: a beginner's guide to the different styles". The Guardian.

- ^ a b "Why Iyengar Yoga?". London: Iyengar Yoga Institute. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ "12 Basic Asanas". Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Centres. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ Lidell 1983, pp. 66–67.

- ^ "Cheat Sheets for the Ashtanga yoga series". Ashtanga Yoga. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ Swenson, David (1999). Ashtanga Yoga: The Practice Manual. Ashtanga Yoga Productions. ISBN 978-1-891252-08-2.

- ^ Mehta, Mehta & Mehta 1990, pp. 188–191.

- ^ Saraswati 1996.

- ^ Moyer, Donald (28 August 2007). "Start Your Home Practice Here: The Basics of Sequencing". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

forward bending, backbending, and twisting. ...standing pose ... sitting ... inverted poses

- ^ Rhodes 2016.

- ^ "Poses". PocketYoga. 2018.

- ^ "Categories of Yoga Poses". Yoga Point. 2018.

- ^ "Yoga Poses". Yogapedia. 2018.

- ^ "Poses by Type". Yoga Journal. 2018.

- ^ "Green Tara, Seated in Pose of Royal Ease (Lalitasana), with Lotus Stalks on Right Shoulder and Hands in Gestures of Reasoning (Vitarkamudra) and Gift Conferring (Varadamudra)". Art Institute Chicago. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ "Śiva". British Museum. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

One leg is raised upon the throne in lalitasana (position of royal ease).

- ^ "Jain Svetambara Tirthankara in Meditation". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ Zimmer, Heinrich (1953) [1952]. Campbell, Joseph (ed.). Philosophies Of India. Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 209–210. ISBN 978-81-208-0739-6.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Hemingway, Mariel (2004) [2002]. Finding My Balance: A Memoir with Yoga. Simon & Schuster. pp. Chapter 1, Chapter 15, and whole book. ISBN 978-0-7432-6432-7.

- ^ Mahadevan-Dasgupta, Uma (11 August 2003). "Striking a fine balance with peace". Business Standard. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ Vilga, Edward (2013). Downward Dog: A Novel. Diversion Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62681-323-6.

- ^ McGee, Kristin (11 June 2013). "'Downward Dog'–A Funny, Sexy, Must Read Book for the Summer!". Kristin McGee. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ Fleming, Ian (1964). You Only Live Twice. pp. Chapter 1.

- ^ Dresner, Lisa M. (2016). ""Barbary Apes Wrecking a Boudoir": Reaffirmations of and Challenges to Western Masculinity in Ian Fleming's Japan Narratives". The Journal of Popular Culture. 49 (3): 627–645. doi:10.1111/jpcu.12422.

Sources

[edit]- Alter, Joseph S. (2004). Yoga in Modern India: The Body between Science and Philosophy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11874-1.

- Bernard, Theos (2007) [1944]. Hatha yoga : the report of a personal experience. Edinburgh: Harmony. ISBN 978-0-9552412-2-2. OCLC 230987898.

- Bharadwaj, S. (1896). Vyayama Dipika, Elements of Gymnastic Exercises, Indian System. Caxton Press. (no OCLC)

- Bukh, Niels (1924). Grundgymnastik eller primitiv Gymnastik. Copenhagen: Hagerup. OCLC 467899046.

- Doniger, Wendy (2011). "God's Body, or, The Lingam Made Flesh: Conflicts over the Representation of the Sexual Body of the Hindu God Shiva". Social Research. 78 (2, Part 1 (Summer 2011)): 485–508. doi:10.1353/sor.2011.0067. JSTOR 23347187. S2CID 170065724.

- Iyengar, B. K. S. (1979) [1966]. Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika. Thorsons. ISBN 978-1-85538-166-7.

- Jain, Andrea (2015). Selling Yoga : from Counterculture to Pop culture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-939024-3. OCLC 878953765.

- Kaminoff, Leslie; Matthews, Amy (2012) [2007]. Yoga Anatomy (2nd ed.). The Breath Trust. ISBN 978-1-4504-0024-4.

- Lidell, Lucy (1983). The Book of Yoga: the complete step-by-step guide. Ebury, for the Sivananda Yoga Centre. ISBN 978-0-85223-297-2. OCLC 12457963.

- Mallinson, James; Singleton, Mark (2017). Roots of Yoga. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-241-25304-5. OCLC 928480104.

- McEvilley, Thomas (1981). "An Archaeology of Yoga". RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics. 1 (1): 44–77. doi:10.1086/RESv1n1ms20166655. JSTOR 20166655. S2CID 192221643.

- Mehta, Silva; Mehta, Mira; Mehta, Shyam (1990). Yoga: The Iyengar Way. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0-86318-420-8.

- Mittra, Dharma (2003). Asanas: 608 Yoga Poses. New World Library. ISBN 978-1-57731-402-8.

- Rhodes, Darren (2016). Yoga Resource Practice Manual. Tirtha Studios. ISBN 978-0-9836883-9-6.

- Samuel, Geoffrey (2017) [2008]. The Origins of Yoga and Tantra. Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521695343.

- Saraswati, Swami Satyananda (1996). Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha (PDF). Yoga Publications Trust. ISBN 978-81-86336-14-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-08-07. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- Shearer, Alistair (2020). The Story of Yoga: From Ancient India to the Modern West. London: Hurst Publishers. ISBN 978-1-78738-192-6.

- Singleton, Mark (2010). Yoga Body : the origins of modern posture practice. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539534-1. OCLC 318191988.

- Sjoman, Norman E. (1999) [1996]. The Yoga Tradition of the Mysore Palace (2nd ed.). Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-389-2.

- Srinivasan, Doris (1984). "Unhinging Śiva from the Indus civilization". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 116 (1): 77–89. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00166134. JSTOR 25211627. S2CID 162904592.

- Vishnu-devananda, Swami (1988) [1960]. The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-517-88431-3.

External links

[edit]- Beyogi Library of Yoga Poses – an illustrated set of asanas with descriptions

- Jack Cuneo Light on Yoga Project; Archived 2021-12-16 at the Wayback Machine – a photographic record of one man's attempt to perform all Iyengar's asanas