Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

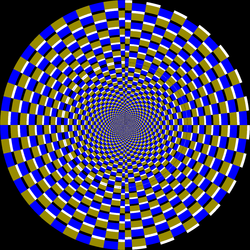

Peripheral drift illusion

View on Wikipedia

The peripheral drift illusion (PDI) refers to a motion illusion generated by the presentation of a sawtooth luminance grating in the visual periphery. This illusion was first described by Faubert and Herbert (1999), although a similar effect called the "escalator illusion" was reported by Fraser and Wilcox (1979). A variant of the PDI was created by Kitaoka Akiyoshi and Ashida (2003) who took the continuous sawtooth luminance change, and reversed the intermediate greys. Kitaoka has created numerous variants of the PDI, and one called "rotating snakes" has become very popular. The latter demonstration has kindled great interest in the PDI.

The illusion is easily seen when fixating off to the side of it, and then blinking as fast as possible. Most observers can see the illusion easily when reading text with the illusion figure in the periphery. The motion of such illusions is consistently perceived in a dark-to-light direction.

Two papers have been published examining the neural mechanisms involved in seeing the PDI (Backus & Oruç, 2005; Conway et al., 2005). Faubert and Herbert (1999) suggested the illusion was based on temporal differences in luminance processing producing a signal that tricks the motion system. Both of the articles from 2005 are broadly consistent with those ideas, although contrast appears to be an important factor (Backus & Oruç, 2005).

Rotating snakes

[edit]

Rotating snakes is an optical illusion developed by Professor Akiyoshi Kitaoka in 2003.[1] A type of peripheral drift illusion, the "snakes" consist of several bands of color which resemble coiled serpents. Although the image is static, the snakes appear to be moving in circles. The speed of perceived motion depends on the frequency of microsaccadic eye movements (Alexander & Martinez-Conde, 2019).

Gallery

[edit]-

Illusion similar to Primrose Field by Kitaoka Akiyoshi

-

A peripheral drift illusion by Paul Nasca

-

A peripheral drift illusion by Paul Nasca

-

Combination of a Café wall illusion and a horizontal peripheral drift illusion

-

A peripheral drift illusion giving a throbbing effect

References

[edit]Inline citations

[edit]General references

[edit]- Alexander, R. G., Martinez-Conde, S. (2019). Fixational eye movements. Eye Movement Research. Springer, Cham, 104–106, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-20085-5_3.

- Backus, B. T., Oruç, İ. (2005). Illusory motion from change over time in the response to contrast and luminance. Journal of Vision, 5(11), 1055–1069, [1], doi:10.1167/5.11.10.

- Conway, B. R., Kitaoka, A., Yazdanbakhsh, A., Pack, C. C., Livingstone, M. S. (2005). Neural basis for a powerful static motion illusion. Journal of Neuroscience, 25, 5651–5656.

- Faubert, J., Herbert, A. M. (1999). The peripheral drift illusion: A motion illusion in the visual periphery. Perception, 28, 617–622.

- Fraser, A., Wilcox, K. J. (1979). Perception of illusory movement. Nature, 281, 565–566.

- Kitaoka. A., Ashida. H. (2003). Phenomenal characteristics of the peripheral drift illusion. Journal of Vision, 15, 261–262.

External links

[edit]- Rotating snakes at Akiyoshi's illusion pages

- Rotating rings at Sarcone's optical illusion pattern page

- These patterns move, but it’s an illusion Archived 2013-09-01 at archive.today by Smithsonian Research Lab

- Does your pet see Peripheral drift? a slideshow designed for testing on animals