Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Neuroscience

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Biology |

|---|

|

Neuroscience is the scientific study of the nervous system (the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nervous system), its functions, and its disorders.[1][2][3] It is a multidisciplinary science that combines physiology, anatomy, molecular biology, developmental biology, cytology, psychology, physics, computer science, chemistry, medicine, statistics, and mathematical modeling to understand the fundamental and emergent properties of neurons, glia, and neural circuits.[4][5][6][7][8] The understanding of the biological basis of learning, memory, behavior, perception, and consciousness has been described by Eric Kandel as the "epic challenge" of the biological sciences.[9]

The scope of neuroscience has broadened over time to include different approaches used to study the nervous system at different scales. The techniques used by neuroscientists have expanded enormously, from molecular and cellular studies of individual neurons to imaging of sensory, motor, and cognitive tasks in the brain.

History

[edit]

The earliest study of the nervous system dates to ancient Egypt. Trepanation, the surgical practice of either drilling or scraping a hole into the skull for the purpose of curing head injuries or mental disorders, or relieving cranial pressure, was first recorded during the Neolithic period. Manuscripts dating to 1700 BC indicate that the Egyptians had some knowledge about symptoms of brain damage.[10]

Early views on the function of the brain regarded it to be a "cranial stuffing" of sorts. In Egypt, from the late Middle Kingdom onwards, the brain was regularly removed in preparation for mummification. It was believed at the time that the heart was the seat of intelligence. According to Herodotus, the first step of mummification was to "take a crooked piece of iron, and with it draw out the brain through the nostrils, thus getting rid of a portion, while the skull is cleared of the rest by rinsing with drugs."[11]

The view that the heart was the source of consciousness was not challenged until the time of the Greek physician Hippocrates. He believed that the brain was not only involved with sensation—since most specialized organs (e.g., eyes, ears, tongue) are located in the head near the brain—but was also the seat of intelligence.[12] Plato also speculated that the brain was the seat of the rational part of the soul.[13] Aristotle, however, believed the heart was the center of intelligence and that the brain regulated the amount of heat from the heart.[14] This view was generally accepted until the Roman physician Galen, a follower of Hippocrates and physician to Roman gladiators, observed that his patients lost their mental faculties when they had sustained damage to their brains.[15]

Abulcasis, Averroes, Avicenna, Avenzoar, and Maimonides, active in the Medieval Muslim world, described a number of medical problems related to the brain. In Renaissance Europe, Vesalius (1514–1564), René Descartes (1596–1650), Thomas Willis (1621–1675) and Jan Swammerdam (1637–1680) also made several contributions to neuroscience.

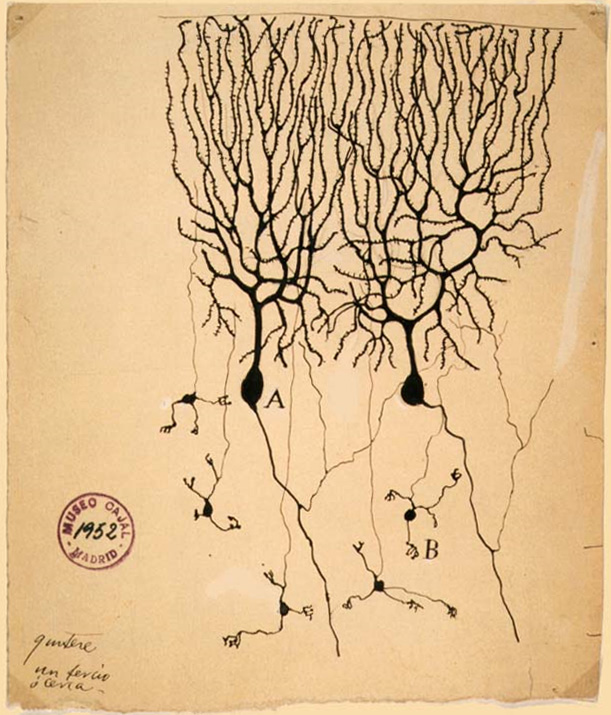

Luigi Galvani's pioneering work in the late 1700s set the stage for studying the electrical excitability of muscles and neurons. In 1843 Emil du Bois-Reymond demonstrated the electrical nature of the nerve signal,[16] whose speed Hermann von Helmholtz proceeded to measure,[17] and in 1875 Richard Caton found electrical phenomena in the cerebral hemispheres of rabbits and monkeys.[18] Adolf Beck published in 1890 similar observations of spontaneous electrical activity of the brain of rabbits and dogs.[19] Studies of the brain became more sophisticated after the invention of the microscope and the development of a staining procedure by Camillo Golgi during the late 1890s. The procedure used a silver chromate salt to reveal the intricate structures of individual neurons. His technique was used by Santiago Ramón y Cajal and led to the formation of the neuron doctrine, the hypothesis that the functional unit of the brain is the neuron.[20] Golgi and Ramón y Cajal shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1906 for their extensive observations, descriptions, and categorizations of neurons throughout the brain.

In parallel with this research, in 1815 Jean Pierre Flourens induced localized lesions of the brain in living animals to observe their effects on motricity, sensibility and behavior. Work with brain-damaged patients by Marc Dax in 1836 and Paul Broca in 1865 suggested that certain regions of the brain were responsible for certain functions. At the time, these findings were seen as a confirmation of Franz Joseph Gall's theory that language was localized and that certain psychological functions were localized in specific areas of the cerebral cortex.[21][22] The localization of function hypothesis was supported by observations of epileptic patients conducted by John Hughlings Jackson, who correctly inferred the organization of the motor cortex by watching the progression of seizures through the body. Carl Wernicke further developed the theory of the specialization of specific brain structures in language comprehension and production. Modern research through neuroimaging techniques, still uses the Brodmann cerebral cytoarchitectonic map (referring to the study of cell structure) anatomical definitions from this era in continuing to show that distinct areas of the cortex are activated in the execution of specific tasks.[23]

During the 20th century, neuroscience began to be recognized as a distinct academic discipline in its own right, rather than as studies of the nervous system within other disciplines. Eric Kandel and collaborators have cited David Rioch, Francis O. Schmitt, and Stephen Kuffler as having played critical roles in establishing the field.[24] Rioch originated the integration of basic anatomical and physiological research with clinical psychiatry at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, starting in the 1950s. During the same period, Schmitt established a neuroscience research program within the Biology Department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, bringing together biology, chemistry, physics, and mathematics. The first freestanding neuroscience department (then called Psychobiology) was founded in 1964 at the University of California, Irvine by James L. McGaugh.[25] This was followed by the Department of Neurobiology at Harvard Medical School, which was founded in 1966 by Stephen Kuffler.[26]

In the process of treating epilepsy, Wilder Penfield produced maps of the location of various functions (motor, sensory, memory, vision) in the brain.[27][28] He summarized his findings in a 1950 book called The Cerebral Cortex of Man.[29] Wilder Penfield and his co-investigators Edwin Boldrey and Theodore Rasmussen are considered to be the originators of the cortical homunculus.[30]

The understanding of neurons and of nervous system function became increasingly precise and molecular during the 20th century. For example, in 1952, Alan Lloyd Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley presented a mathematical model for the transmission of electrical signals in neurons of the giant axon of a squid, which they called "action potentials", and how they are initiated and propagated, known as the Hodgkin–Huxley model. In 1961–1962, Richard FitzHugh and J. Nagumo simplified Hodgkin–Huxley, in what is called the FitzHugh–Nagumo model. In 1962, Bernard Katz modeled neurotransmission across the space between neurons known as synapses. Beginning in 1966, Eric Kandel and collaborators examined biochemical changes in neurons associated with learning and memory storage in Aplysia. In 1981 Catherine Morris and Harold Lecar combined these models in the Morris–Lecar model. Such increasingly quantitative work gave rise to numerous biological neuron models and models of neural computation.

As a result of the increasing interest about the nervous system, several prominent neuroscience organizations have been formed to provide a forum to all neuroscientists during the 20th century. For example, the International Brain Research Organization was founded in 1961,[31] the International Society for Neurochemistry in 1963,[32] the European Brain and Behaviour Society in 1968,[33] and the Society for Neuroscience in 1969.[34] Recently, the application of neuroscience research results has also given rise to applied disciplines as neuroeconomics,[35] neuroeducation,[36] neuroethics,[37] and neurolaw.[38]

Over time, brain research has gone through philosophical, experimental, and theoretical phases, with work on neural implants and brain simulation predicted to be important in the future.[39]

Modern neuroscience

[edit]

The scientific study of the nervous system increased significantly during the second half of the twentieth century, principally due to advances in molecular biology, electrophysiology, and computational neuroscience. This has allowed neuroscientists to study the nervous system in all its aspects: how it is structured, how it works, how it develops, how it malfunctions, and how it can be changed.

For example, it has become possible to understand, in much detail, the complex processes occurring within a single neuron. Neurons are cells specialized for communication. They are able to communicate with neurons and other cell types through specialized junctions called synapses, at which electrical or electrochemical signals can be transmitted from one cell to another. Many neurons extrude a long thin filament of axoplasm called an axon, which may extend to distant parts of the body and are capable of rapidly carrying electrical signals, influencing the activity of other neurons, muscles, or glands at their termination points. A nervous system emerges from the assemblage of neurons that are connected to each other in neural circuits, and networks.

The vertebrate nervous system can be split into two parts: the central nervous system (defined as the brain and spinal cord), and the peripheral nervous system. In many species—including all vertebrates—the nervous system is the most complex organ system in the body, with most of the complexity residing in the brain. The human brain alone contains around one hundred billion neurons and one hundred trillion synapses; it consists of thousands of distinguishable substructures, connected to each other in synaptic networks whose intricacies have only begun to be unraveled. At least one out of three of the approximately 20,000 genes belonging to the human genome is expressed mainly in the brain.[40]

Due to the high degree of plasticity of the human brain, the structure of its synapses and their resulting functions change throughout life.[41]

Making sense of the nervous system's dynamic complexity is a formidable research challenge. Ultimately, neuroscientists would like to understand every aspect of the nervous system, including how it works, how it develops, how it malfunctions, and how it can be altered or repaired. Analysis of the nervous system is therefore performed at multiple levels, ranging from the molecular and cellular levels to the systems and cognitive levels. The specific topics that form the main focus of research change over time, driven by an ever-expanding base of knowledge and the availability of increasingly sophisticated technical methods. Improvements in technology have been the primary drivers of progress. Developments in electron microscopy, computer science, electronics, functional neuroimaging, and genetics and genomics have all been major drivers of progress.

Advances in the classification of brain cells have been enabled by electrophysiological recording, single-cell genetic sequencing, and high-quality microscopy, which have combined into a single method pipeline called patch-sequencing in which all three methods are simultaneously applied using miniature tools.[42] The efficiency of this method and the large amounts of data that is generated has allowed researchers to make some general conclusions about cell types; for example that the human and mouse brain have different versions of fundamentally the same cell types.[43]

Molecular and cellular neuroscience

[edit]

Basic questions addressed in molecular neuroscience include the mechanisms by which neurons express and respond to molecular signals and how axons form complex connectivity patterns. At this level, tools from molecular biology and genetics are used to understand how neurons develop and how genetic changes affect biological functions.[44] The morphology, molecular identity, and physiological characteristics of neurons and how they relate to different types of behavior are also of considerable interest.[45]

Questions addressed in cellular neuroscience include the mechanisms of how neurons process signals physiologically and electrochemically. These questions include how signals are processed by neurites and somas and how neurotransmitters and electrical signals are used to process information in a neuron. Neurites are thin extensions from a neuronal cell body, consisting of dendrites (specialized to receive synaptic inputs from other neurons) and axons (specialized to conduct nerve impulses called action potentials). Somas are the cell bodies of the neurons and contain the nucleus.[46]

Another major area of cellular neuroscience is the investigation of the development of the nervous system.[47] Questions include the patterning and regionalization of the nervous system, axonal and dendritic development, trophic interactions, synapse formation and the implication of fractones in neural stem cells,[48][49] differentiation of neurons and glia (neurogenesis and gliogenesis), and neuronal migration.[50]

Computational neurogenetic modeling is concerned with the development of dynamic neuronal models for modeling brain functions with respect to genes and dynamic interactions between genes, on the cellular level (Computational Neurogenetic Modeling (CNGM) can also be used to model neural systems).[51]

Neural circuits and systems

[edit]

Systems neuroscience research centers on the structural and functional architecture of the developing human brain, and the functions of large-scale brain networks, or functionally-connected systems within the brain. Alongside brain development, systems neuroscience also focuses on how the structure and function of the brain enables or restricts the processing of sensory information, using learned mental models of the world, to motivate behavior.

Questions in systems neuroscience include how neural circuits are formed and used anatomically and physiologically to produce functions such as reflexes, multisensory integration, motor coordination, circadian rhythms, emotional responses, learning, and memory.[52] In other words, this area of research studies how connections are made and morphed in the brain, and the effect it has on human sensation, movement, attention, inhibitory control, decision-making, reasoning, memory formation, reward, and emotion regulation.[53]

Specific areas of interest for the field include observations of how the structure of neural circuits effect skill acquisition, how specialized regions of the brain develop and change (neuroplasticity), and the development of brain atlases, or wiring diagrams of individual developing brains.[54]

The related fields of neuroethology and neuropsychology address the question of how neural substrates underlie specific animal and human behaviors.[55] Neuroendocrinology and psychoneuroimmunology examine interactions between the nervous system and the endocrine and immune systems, respectively.[56] Despite many advancements, the way that networks of neurons perform complex cognitive processes and behaviors is still poorly understood.[57]

Cognitive and behavioral neuroscience

[edit]Cognitive neuroscience addresses the questions of how psychological functions are produced by neural circuitry. The emergence of powerful new measurement techniques such as neuroimaging (e.g., fMRI, PET, SPECT), EEG, MEG, electrophysiology, optogenetics and human genetic analysis combined with sophisticated experimental techniques from cognitive psychology allows neuroscientists and psychologists to address abstract questions such as how cognition and emotion are mapped to specific neural substrates. Although many studies hold a reductionist stance looking for the neurobiological basis of cognitive phenomena, recent research shows that there is an interplay between neuroscientific findings and conceptual research, soliciting and integrating both perspectives. For example, neuroscience research on empathy solicited an interdisciplinary debate involving philosophy, psychology and psychopathology.[58] Moreover, the neuroscientific identification of multiple memory systems related to different brain areas has challenged the idea of memory as a literal reproduction of the past, supporting a view of memory as a generative, constructive and dynamic process.[59]

Neuroscience is also allied with the social and behavioral sciences, as well as with nascent interdisciplinary fields. Examples of such alliances include neuroeconomics, decision theory, social neuroscience, and neuromarketing to address complex questions about interactions of the brain with its environment. A study into consumer responses for example uses EEG to investigate neural correlates associated with narrative transportation into stories about energy efficiency.[60]

Computational neuroscience

[edit]Questions in computational neuroscience can span a wide range of levels of traditional analysis, such as development, structure, and cognitive functions of the brain. Research in this field utilizes mathematical models, theoretical analysis, and computer simulation to describe and verify biologically plausible neurons and nervous systems. For example, biological neuron models are mathematical descriptions of spiking neurons which can be used to describe both the behavior of single neurons as well as the dynamics of neural networks. Computational neuroscience is often referred to as theoretical neuroscience.

Neuroscience and medicine

[edit]Clinical neuroscience

[edit]Neurology, psychiatry, neurosurgery, psychosurgery, anesthesiology and pain medicine, neuropathology, neuroradiology, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, clinical neurophysiology, addiction medicine, and sleep medicine are some medical specialties that specifically address the diseases of the nervous system. These terms also refer to clinical disciplines involving diagnosis and treatment of these diseases.[61]

Neurology works with diseases of the central and peripheral nervous systems, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and stroke, and their medical treatment. Psychiatry focuses on affective, behavioral, cognitive, and perceptual disorders. Anesthesiology focuses on perception of pain, and pharmacologic alteration of consciousness. Neuropathology focuses upon the classification and underlying pathogenic mechanisms of central and peripheral nervous system and muscle diseases, with an emphasis on morphologic, microscopic, and chemically observable alterations. Neurosurgery and psychosurgery work primarily with surgical treatment of diseases of the central and peripheral nervous systems.[62]

Neuroscience underlies the development of various neurotherapy methods to treat diseases of the nervous system.[63][64][65]

Translational research

[edit]

Recently, the boundaries between various specialties have blurred, as they are all influenced by basic research in neuroscience. For example, brain imaging enables objective biological insight into mental illnesses, which can lead to faster diagnosis, more accurate prognosis, and improved monitoring of patient progress over time.[66]

Integrative neuroscience describes the effort to combine models and information from multiple levels of research to develop a coherent model of the nervous system. For example, brain imaging coupled with physiological numerical models and theories of fundamental mechanisms may shed light on psychiatric disorders.[67]

Another important area of translational research is brain–computer interfaces (BCIs), or machines that are able to communicate and influence the brain. They are currently being researched for their potential to repair neural systems and restore certain cognitive functions.[68] However, some ethical considerations have to be dealt with before they are accepted.[69][70]

Major branches

[edit]Modern neuroscience education and research activities can be very roughly categorized into the following major branches, based on the subject and scale of the system in examination as well as distinct experimental or curricular approaches. Individual neuroscientists, however, often work on questions that span several distinct subfields.

| Branch | Description |

|---|---|

| Affective neuroscience | Affective neuroscience is the study of the neural mechanisms involved in emotion, typically through experimentation on animal models.[71] |

| Behavioral neuroscience | Behavioral neuroscience (also known as biological psychology, physiological psychology, biopsychology, or psychobiology) is the application of the principles of biology to the study of genetic, physiological, and developmental mechanisms of behavior in humans and non-human animals.[72] |

| Cellular neuroscience | Cellular neuroscience is the study of neurons at a cellular level including morphology and physiological properties.[73] |

| Clinical neuroscience | The scientific study of the biological mechanisms that underlie the disorders and diseases of the nervous system.[74] |

| Cognitive neuroscience | Cognitive neuroscience is the study of the biological mechanisms underlying cognition.[74] |

| Computational neuroscience | Computational neuroscience is the theoretical study of the nervous system.[75] |

| Cultural neuroscience | Cultural neuroscience is the study of how cultural values, practices and beliefs shape and are shaped by the mind, brain and genes across multiple timescales.[76] |

| Developmental neuroscience | Developmental neuroscience studies the processes that generate, shape, and reshape the nervous system and seeks to describe the cellular basis of neural development to address underlying mechanisms.[77] |

| Evolutionary neuroscience | Evolutionary neuroscience studies the evolution of nervous systems.[78] |

| Molecular neuroscience | Molecular neuroscience studies the nervous system with molecular biology, molecular genetics, protein chemistry, and related methodologies.[79] |

| Nanoneuroscience | An interdisciplinary field that integrates nanotechnology and neuroscience.[80] |

| Neural engineering | Neural engineering uses engineering techniques to interact with, understand, repair, replace, or enhance neural systems.[81] |

| Neuroanatomy | Neuroanatomy is the study of the anatomy of nervous systems.[82] |

| Neurochemistry | Neurochemistry is the study of how neurochemicals interact and influence the function of neurons.[83] |

| Neuroethology | Neuroethology is the study of the neural basis of non-human animals behavior. |

| Neurogastronomy | Neurogastronomy is the study of flavor and how it affects sensation, cognition, and memory.[84] |

| Neurogenetics | Neurogenetics is the study of the genetical basis of the development and function of the nervous system.[85] |

| Neuroimaging | Neuroimaging includes the use of various techniques to either directly or indirectly image the structure and function of the brain.[86] |

| Neuroimmunology | Neuroimmunology is concerned with the interactions between the nervous and the immune system.[87] |

| Neuroinformatics | Neuroinformatics is a discipline within bioinformatics that conducts the organization of neuroscience data and application of computational models and analytical tools.[88] |

| Neurolinguistics | Neurolinguistics is the study of the neural mechanisms in the human brain that control the comprehension, production, and acquisition of language.[89][74] |

| Neuro-ophthalmology | Neuro-ophthalmology is an academically oriented subspecialty that merges the fields of neurology and ophthalmology, often dealing with complex systemic diseases that have manifestations in the visual system. |

| Neurophysics | Neurophysics is the branch of biophysics dealing with the development and use of physical methods to gain information about the nervous system.[90] |

| Neurophysiology | Neurophysiology is the study of the structure and function of the nervous system, generally using physiological techniques that include measurement and stimulation with electrodes or optically with ion- or voltage-sensitive dyes or light-sensitive channels.[91] |

| Neuropsychology | Neuropsychology is a discipline that resides under the umbrellas of both psychology and neuroscience, and is involved in activities in the arenas of both basic science and applied science. In psychology, it is most closely associated with biopsychology, clinical psychology, cognitive psychology, and developmental psychology. In neuroscience, it is most closely associated with the cognitive, behavioral, social, and affective neuroscience areas. In the applied and medical domain, it is related to neurology and psychiatry.[92] |

| Neuropsychopharmacology | Neuropsychopharmacology, an interdisciplinary science related to psychopharmacology and fundamental neuroscience, is the study of the neural mechanisms that drugs act upon to influence behavior.[93] |

| Optogenetics | Optogenetics is a biological technique to control the activity of neurons or other cell types with light. |

| Paleoneurobiology | Paleoneurobiology is a field that combines techniques used in paleontology and archeology to study brain evolution, especially that of the human brain.[94] |

| Social neuroscience | Social neuroscience is an interdisciplinary field devoted to understanding how biological systems implement social processes and behavior, and to using biological concepts and methods to inform and refine theories of social processes and behavior.[95] |

| Systems neuroscience | Systems neuroscience is the study of the function of neural circuits and systems.[96] |

Careers in neuroscience

[edit]The career options for neuroscience graduates vary widely depending on the level of education. At the bachelor’s level, graduates often enter laboratory research, healthcare support, biotechnology, or science communication, though some pursue broader fields such as policy or nonprofit work. With a master’s degree, training may prepare individuals for applied health professions (e.g., occupational therapy, medicine -neurology, psychiatry, neuroimaging-, genetic counseling), research management, or public health. An advanced degree (PhD or equivalent) is usually required for independent research or university teaching. Source:[97]

Bachelor's Level

[edit]| Pharmaceutical Sales | Residential Counselor |

| Laboratory Technician | Regulatory Affairs Specialist |

| Psychometrist* | Medical Technician* |

| Science Writer | Clinical Research Assistant |

| Science Advocacy | Special Education Assistant |

| Nonprofit Work | Patient Care Assistant* |

| Health Educator | Orthotic and Prosthetic Technician* |

| EEG Technologist* | Lab Animal Care Technician |

| Medical and Healthcare Manager | Sales Engineer |

| Forensic Science Technician | Law Enforcement |

| Pharmacy Technician* | Natural Sciences Manager |

| Public Policy | Advertising/Marketing |

Master's Level

[edit]| Nurse Practitioner | Neuroimaging Technician |

| Physician's Assistant | Teacher |

| Genetic Counselor | Epidemiology |

| Occupational Therapist | Biostatistician |

| Orthotist/Prosthetist | Speech-Language Pathologist |

| Neural Engineer | Public Health |

Advanced Degree

[edit]| Medicine (MD, DO) | Food Scientist |

| Research Scientist | Pharmacist |

| Dentist | Veterinarian |

| Physical Therapist | Audiologist |

| Optometrist | Lawyer |

| Clinical Psychologist | Professor |

| Neuropsychologist | Chiropractor |

Neuroscience organizations

[edit]The largest professional neuroscience organization is the Society for Neuroscience (SFN), which is based in the United States but includes many members from other countries. Since its founding in 1969 the SFN has grown steadily: as of 2010 it recorded 40,290 members from 83 countries.[98] Annual meetings, held each year in a different American city, draw attendance from researchers, postdoctoral fellows, graduate students, and undergraduates, as well as educational institutions, funding agencies, publishers, and hundreds of businesses that supply products used in research.

Other major organizations devoted to neuroscience include the International Brain Research Organization (IBRO), which holds its meetings in a country from a different part of the world each year, and the Federation of European Neuroscience Societies (FENS), which holds a meeting in a different European city every two years. FENS comprises a set of 32 national-level organizations, including the British Neuroscience Association, the German Neuroscience Society (Neurowissenschaftliche Gesellschaft), and the French Société des Neurosciences.[99] The first National Honor Society in Neuroscience, Nu Rho Psi, was founded in 2006. Numerous youth neuroscience societies which support undergraduates, graduates and early career researchers also exist, such as Simply Neuroscience[100] and Project Encephalon.[101]

In 2013, the BRAIN Initiative was announced in the US. The International Brain Initiative[102] was created in 2017,[103] currently integrated by more than seven national-level brain research initiatives (US, Europe, Allen Institute, Japan, China, Australia,[104] Canada,[105] Korea,[106] and Israel[107])[108] spanning four continents.

Public education and outreach

[edit]In addition to conducting traditional research in laboratory settings, neuroscientists have also been involved in the promotion of awareness and knowledge about the nervous system among the general public and government officials. Such promotions have been done by both individual neuroscientists and large organizations. For example, individual neuroscientists have promoted neuroscience education among young students by organizing the International Brain Bee, which is an academic competition for high school or secondary school students worldwide.[109] In the United States, large organizations such as the Society for Neuroscience have promoted neuroscience education by developing a primer called Brain Facts,[110] collaborating with public school teachers to develop Neuroscience Core Concepts for K-12 teachers and students,[111] and cosponsoring a campaign with the Dana Foundation called Brain Awareness Week to increase public awareness about the progress and benefits of brain research.[112] In Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research's (CIHR) Canadian National Brain Bee is held annually at McMaster University.[113]

Neuroscience educators formed a Faculty for Undergraduate Neuroscience (FUN) in 1992 to share best practices and provide travel awards for undergraduates presenting at Society for Neuroscience meetings.[114]

Neuroscientists have also collaborated with other education experts to study and refine educational techniques to optimize learning among students, an emerging field called educational neuroscience.[115] Federal agencies in the United States, such as the National Institute of Health (NIH)[116] and National Science Foundation (NSF),[117] have also funded research that pertains to best practices in teaching and learning of neuroscience concepts.

Engineering applications of neuroscience

[edit]Neuromorphic computer chips

[edit]Neuromorphic engineering is a branch of neuroscience that deals with creating functional physical models of neurons for the purposes of useful computation[118][119]. The emergent computational properties of neuromorphic computers are fundamentally different from conventional computers in the sense that they are complex systems, and that the computational components are interrelated with no central processor.[120]

One example of such a computer is the SpiNNaker supercomputer.[121]

Sensors can also be made smart with neuromorphic technology. An example of this is the Event Camera's BrainScaleS (brain-inspired Multiscale Computation in Neuromorphic Hybrid Systems), a hybrid analog neuromorphic supercomputer located at Heidelberg University in Germany. It was developed as part of the Human Brain Project's neuromorphic computing platform and is the complement to the SpiNNaker supercomputer, which is based on digital technology. The architecture used in BrainScaleS mimics biological neurons and their connections on a physical level; additionally, since the components are made of silicon, these model neurons operate on average 864 times (24 hours of real time is 100 seconds in the machine simulation) that of their biological counterparts.[122]

Recent advances in neuromorphic microchip technology have led a group of scientists to create an artificial neuron that can replace real neurons in diseases.[123][124]

Nobel prizes related to neuroscience

[edit]| Year | Prize field | Image | Laureate | Lifetime | Country | Rationale | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1904 | Physiology |

|

Ivan Petrovich Pavlov | 1849–1936 | Russian Empire | "in recognition of his work on the physiology of digestion, through which knowledge on vital aspects of the subject has been transformed and enlarged" | [125] |

| 1906 | Physiology |

|

Camillo Golgi | 1843–1926 | Kingdom of Italy | "in recognition of their work on the structure of the nervous system" | [126] |

|

Santiago Ramón y Cajal | 1852–1934 | Restoration (Spain) | ||||

| 1911 | Physiology |

|

Allvar Gullstrand | 1862– 1930 | Sweden | "for his work on the dioptrics of the eye" | [127] |

| 1914 | Physiology |

|

Robert Bárány | 1876–1936 | Austria-Hungary | "for his work on the physiology and pathology of the vestibular apparatus" | [128] |

| 1932 | Physiology |

|

Charles Scott Sherrington | 1857–1952 | United Kingdom | "for their discoveries regarding the functions of neurons" | [129] |

|

Edgar Douglas Adrian | 1889–1977 | United Kingdom | ||||

| 1936 | Physiology |

|

Henry Hallett Dale | 1875–1968 | United Kingdom | "for their discoveries relating to chemical transmission of nerve impulses" | [130] |

|

Otto Loewi | 1873–1961 | Austria Germany | ||||

| 1938 | Physiology |

|

Corneille Jean François Heymans | 1892–1968 | Belgium | "for the discovery of the role played by the sinus and aortic mechanisms in the regulation of respiration" | [131] |

| 1944 | Physiology |

|

Joseph Erlanger | 1874–1965 | United States | "for their discoveries relating to the highly differentiated functions of single nerve fibres" | [132] |

|

Herbert Spencer Gasser | 1888–1963 | United States | ||||

| 1949 | Physiology |

|

Walter Rudolf Hess | 1881–1973 | Switzerland | "for his discovery of the functional organization of the interbrain as a coordinator of the activities of the internal organs" | [133] |

|

António Caetano Egas Moniz | 1874–1955 | Portugal | "for his discovery of the therapeutic value of leucotomy in certain psychoses" | [133] | ||

| 1955 | Chemistry |

|

Vincent du Vigneaud | 1901–1978 | United States | "for his work on biochemically important sulphur compounds, especially for the first synthesis of a polypeptide hormone" (Oxytocin) | [134] |

| 1957 | Physiology |

|

Daniel Bovet | 1907–1992 | Italy | "for his discoveries relating to synthetic compounds that inhibit the action of certain body substances, and especially their action on the vascular system and the skeletal muscles" | [135] |

| 1961 | Physiology |

|

Georg von Békésy | 1899–1972 | United States | "for his discoveries of the physical mechanism of stimulation within the cochlea" | [136] |

| 1963 | Physiology |

|

John Carew Eccles | 1903–1997 | Australia | "for their discoveries concerning the ionic mechanisms involved in excitation and inhibition in the peripheral and central portions of the nerve cell membrane" | [137] |

|

Alan Lloyd Hodgkin | 1914–1998 | United Kingdom | ||||

|

Andrew Fielding Huxley | 1917–2012 | United Kingdom | ||||

| 1967 | Physiology |

|

Ragnar Granit | 1900–1991 | Finland Sweden |

"for their discoveries concerning the primary physiological and chemical visual processes in the eye" | [138] |

|

Haldan Keffer Hartline | 1903–1983 | United States | ||||

|

George Wald | 1906–1997 | United States | ||||

| 1970 | Physiology | Julius Axelrod | 1912–2004 | United States | "for their discoveries concerning the humoral transmittors in the nerve terminals and the mechanism for their storage, release and inactivation" | [137] | |

|

Ulf von Euler | 1905–1983 | Sweden | ||||

| Bernard Katz | 1911–2003 | United Kingdom | |||||

| 1973 | Physiology |

|

Karl von Frisch | 1886–1982 | Austria | "for their discoveries concerning organization and elicitation of individual and social behaviour patterns" | [139] |

|

Konrad Lorenz | 1903–1989 | Austria | ||||

|

Nikolaas Tinbergen | 1907–1988 | Netherlands | ||||

| 1977 | Physiology |

|

Roger Guillemin | 1924–2024 | France | "for their discoveries concerning the peptide hormone production of the brain" | [140] |

|

Andrew V. Schally | 1926–2024 | Poland | ||||

| 1981 | Physiology |

|

Roger W. Sperry | 1913–1994 | United States | "for his discoveries concerning the functional specialization of the cerebral hemispheres" | [138] |

|

David H. Hubel | 1926–2013 | Canada | "for their discoveries concerning information processing in the visual system" | [138] | ||

|

Torsten N. Wiesel | 1924– | Sweden | ||||

| 1986 | Physiology |

|

Stanley Cohen | 1922–2020 | United States | "for their discoveries of growth factors" | [141] |

|

Rita Levi-Montalcini | 1909–2012 | Italy | ||||

| 1991 | Physiology |

|

Erwin Neher | 1944– | Germany | "For their discoveries concerning the function of single ion channels in cells" | [142] |

|

Bert Sakmann | 1942– | Germany | ||||

| 1997 | Physiology |

|

Stanley B. Prusiner | 1942– | United States | "for his discovery of Prions - a new biological principle of infection" | [143] |

| 1997 | Chemistry |

|

Jens C. Skou | 1918–2018 | Denmark | "for the first discovery of an ion-transporting enzyme, Na+, K+ -ATPase" | [144] |

| 2000 | Physiology |

|

Arvid Carlsson | 1923–2018 | Sweden | "for their discoveries concerning signal transduction in the nervous system" | [145] |

|

Paul Greengard | 1925–2019 | United States | ||||

|

Eric R. Kandel | 1929– | United States | ||||

| 2003 | Chemistry |

|

Roderick MacKinnon | 1956– | United States | "for discoveries concerning channels in cell membranes [...] for structural and mechanistic studies of ion channels" | [146] |

| 2004 | Physiology |

|

Richard Axel | 1946– | United States | "for their discoveries of odorant receptors and the organization of the olfactory system" | [147] |

|

Linda B. Buck | 1947– | United States | ||||

| 2012 | Chemistry |

|

Robert Lefkowitz | 1943– | United States | "for studies of G-protein-coupled receptors"" | [148] |

|

Brian Kobilka | 1955– | United States | ||||

| 2014 | Physiology |

|

John O'Keefe | 1939– | United States United Kingdom |

"for their discoveries of place and grid cells that constitute a positioning system in the brain" | [149] |

|

May-Britt Moser | 1963– | Norway | ||||

|

Edvard I. Moser | 1962– | Norway | ||||

| 2017 | Physiology |

|

Jeffrey C. Hall | 1939– | United States | "for their discoveries of molecular mechanisms controlling the circadian rhythm" | [150] |

|

Michael Rosbash | 1944– | United States | ||||

|

Michael W. Young | 1949– | United States | ||||

| 2021 | Physiology |

|

David Julius | 1955– | United States | "for their discoveries of receptors for temperature and touch" | [151] |

|

Ardem Patapoutian | 1967– | Lebanon

United States | ||||

| 2024 | Physics |

|

John Hopfield | 1933– | United States | "for foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks" | [152] |

|

Geoffrey Hinton | 1947– | United Kingdom |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Neuroscience". Merriam-Webster Medical Dictionary. 31 March 2025.

- ^ "Key Brain Terms Glossary". Dana Foundation.

- ^ "What is neuroscience?". King's College London. School of Neuroscience.

- ^ Kandel, Eric R. (2012). Principles of Neural Science, Fifth Edition. McGraw-Hill Education. pp. I. Overall perspective. ISBN 978-0-07-139011-8.

- ^ Ayd, Frank J. Jr. (2000). Lexicon of Psychiatry, Neurology and the Neurosciences. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. p. 688. ISBN 978-0-7817-2468-5.

- ^ Shulman, Robert G. (2013). "Neuroscience: A Multidisciplinary, Multilevel Field". Brain Imaging: What it Can (and Cannot) Tell Us About Consciousness. Oxford University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-19-983872-1.

- ^ Ogawa, Hiroto; Oka, Kotaro (2013). Methods in Neuroethological Research. Springer. p. v. ISBN 978-4-431-54330-5.

- ^ Tanner, Kimberly D. (2006-01-01). "Issues in Neuroscience Education: Making Connections". CBE: Life Sciences Education. 5 (2): 85. doi:10.1187/cbe.06-04-0156. ISSN 1931-7913. PMC 1618510.

- ^ Kandel, Eric R. (2012). Principles of Neural Science, Fifth Edition. McGraw-Hill Education. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-07-139011-8.

The last frontier of the biological sciences – their ultimate challenge – is to understand the biological basis of consciousness and the mental processes by which we perceive, act, learn, and remember.

- ^ Mohamed W (2008). "The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus: Neuroscience in Ancient Egypt". IBRO History of Neuroscience. Archived from the original on 2014-07-06. Retrieved 2014-07-06.

- ^ Herodotus (2009) [440 BCE]. The Histories: Book II (Euterpe). Translated by George Rawlinson.

- ^ Breitenfeld, T.; Jurasic, M. J.; Breitenfeld, D. (September 2014). "Hippocrates: the forefather of neurology". Neurological Sciences. 35 (9): 1349–1352. doi:10.1007/s10072-014-1869-3. ISSN 1590-3478. PMID 25027011. S2CID 2002986.

- ^ Plato (2009) [360 BCE]. Timaeus. Translated by George Rawlinson.

- ^ Finger, Stanley (2001). Origins of Neuroscience: A History of Explorations into Brain Function (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 3–17. ISBN 978-0-19-514694-3.

- ^ Freemon, F. R. (23 Sep 2009). "Galen's ideas on neurological function". Journal of the History of the Neurosciences. 3 (4): 263–271. doi:10.1080/09647049409525619. ISSN 0964-704X. PMID 11618827.

- ^ Finkelstein, Gabriel (2013). Emil du Bois-Reymond: Neuroscience, Self, and Society in Nineteenth-Century Germany. Cambridge; London: The MIT Press. pp. 72–74, 89–95. ISBN 978-0-262-01950-7.

- ^ Harrison, David W. (2015). Brain Asymmetry and Neural Systems Foundations in Clinical Neuroscience and Neuropsychology. Springer International Publishing. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-3-319-13068-2.

- ^ "Caton, Richard - The electric currents of the brain". echo.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- ^ Coenen, Anton; Edward Fine; Oksana Zayachkivska (2014). "Adolf Beck: A Forgotten Pioneer In Electroencephalography". Journal of the History of the Neurosciences. 23 (3): 276–286. doi:10.1080/0964704x.2013.867600. PMID 24735457. S2CID 205664545.

- ^ Guillery, R (Jun 2005). "Observations of synaptic structures: origins of the neuron doctrine and its current status". Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 360 (1458): 1281–307. doi:10.1098/rstb.2003.1459. PMC 1569502. PMID 16147523.

- ^ Greenblatt SH (1995). "Phrenology in the science and culture of the 19th century". Neurosurgery. 37 (4): 790–805. doi:10.1227/00006123-199510000-00025. PMID 8559310.

- ^ Bear MF; Connors BW; Paradiso MA (2001). Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-3944-3.

- ^ Kandel ER; Schwartz JH; Jessel TM (2000). Principles of Neural Science (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-8385-7701-1.

- ^ Cowan, W.M.; Harter, D.H.; Kandel, E.R. (2000). "The emergence of modern neuroscience: Some implications for neurology and psychiatry". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 23 (1): 345–346. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.343. PMID 10845068.

- ^ Squire, Larry R. (1996). "James L. McGaugh". The History of Neuroscience in Autobiography. Vol. 4. Washington DC: Society for Neuroscience. p. 410. ISBN 0-916110-51-6. OCLC 36433905.

- ^ "History - Department of Neurobiology". Archived from the original on 2019-09-27. Retrieved 2017-10-17.

- ^ Wilder Penfield redrew the map of the brain — by opening the heads of living patients

- ^ Kumar, R.; Yeragani, V. K. (2011). "Penfield – A great explorer of psyche-soma-neuroscience". Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 53 (3): 276–278. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.86826. PMC 3221191. PMID 22135453.

- ^ Schott, G. D. (1993). "Penfield's homunculus: A note on cerebral cartography" (PDF). Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 56 (4): 329–333. doi:10.1136/jnnp.56.4.329. PMC 1014945. PMID 8482950.

- ^ Cazala, Fadwa; Vienney, Nicolas; Stoléru, Serge (2015-03-10). "The cortical sensory representation of genitalia in women and men: a systematic review". Socioaffective Neuroscience & Psychology. 5 26428. doi:10.3402/snp.v5.26428. PMC 4357265. PMID 25766001.

- ^ "History of IBRO". International Brain Research Organization. 2010.

- ^ Portal, ISN. "The Beginning". www.neurochemistry.org. Archived from the original on 2012-04-21. Retrieved 2025-04-11.

- ^ "About EBBS". European Brain and Behaviour Society. 2009. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03.

- ^ "About SfN". Society for Neuroscience.

- ^ "How can neuroscience inform economics?" (PDF). Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences.

- ^ Zull, J. (2002). The art of changing the brain: Enriching the practice of teaching by exploring the biology of learning. Sterling, Virginia: Stylus Publishing, LLC

- ^ "What is Neuroethics?". www.neuroethicssociety.org. Archived from the original on 2019-04-05. Retrieved 2019-02-22.

- ^ Petoft, Arian (2015-01-05). "Neurolaw: A brief introduction". Iranian Journal of Neurology. 14 (1): 53–58. ISSN 2008-384X. PMC 4395810. PMID 25874060.

- ^ Fan, Xue; Markram, Henry (2019-05-07). "A Brief History of Simulation Neuroscience". Frontiers in Neuroinformatics. 13 32. doi:10.3389/fninf.2019.00032. ISSN 1662-5196. PMC 6513977. PMID 31133838.

- ^ "Brain Basics: Genes At Work In The Brain | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". www.ninds.nih.gov. Retrieved 2025-04-11.

- ^ "The Fundamentals of Mental Health and Mental Illness" (PDF). resources.saylor.org.

- ^ Lipovsek, Marcela; Bardy, Cedric; Cadwell, Cathryn R.; et al. (3 February 2021). "Patch-seq: Past, Present, and Future". The Journal of Neuroscience. 41 (5): 937–946. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1653-20.2020. PMC 7880286. PMID 33431632.

- ^ Hodge, Rebecca D.; Bakken, Trygve E.; Miller, Jeremy A.; et al. (5 September 2019). "Conserved cell types with divergent features in human versus mouse cortex". Nature. 573 (7772): 61–68. Bibcode:2019Natur.573...61H. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1506-7. PMC 6919571. PMID 31435019.

- ^ "Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience | UCSB Neuroscience | UC Santa Barbara". Neuroscience.ucsb.edu. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- ^ Byrne, John H.; Heidelberger, Ruth; Waxham, M. Neal, eds. (2014). From Molecules to Networks. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/C2011-0-07251-4. ISBN 978-0-12-397179-1.[page needed]

- ^ Flynn, Kevin C (July 2013). "The cytoskeleton and neurite initiation". BioArchitecture. 3 (4): 86–109. doi:10.4161/bioa.26259. PMC 4201609. PMID 24002528.

- ^ Alberts, Bruce; Johnson, Alexander; Lewis, Julian; Raff, Martin; Roberts, Keith; Walter, Peter (2002). "Neural Development". Molecular Biology of the Cell (4 ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ Nascimento, Marcos Assis; Sorokin, Lydia; Coelho-Sampaio, Tatiana (2018-04-18). "Fractone Bulbs Derive from Ependymal Cells and Their Laminin Composition Influence the Stem Cell Niche in the Subventricular Zone". Journal of Neuroscience. 38 (16): 3880–3889. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3064-17.2018. ISSN 0270-6474. PMC 6705924. PMID 29530987.

- ^ Mercier, Frederic (2016). "Fractones: extracellular matrix niche controlling stem cell fate and growth factor activity in the brain in health and disease". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 73 (24): 4661–4674. doi:10.1007/s00018-016-2314-y. ISSN 1420-682X. PMC 11108427. PMID 27475964. S2CID 28119663.

- ^ Mercier, Frederic; Arikawa-Hirasawa, Eri (2012). "Heparan sulfate niche for cell proliferation in the adult brain". Neuroscience Letters. 510 (2): 67–72. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2011.12.046. PMID 22230891. S2CID 27352770.

- ^ "Neuroscience Research Areas". NYU Grossman School of Medicine. NYU Langone Health Neuroscience Institute. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ Tau, Gregory Z; Peterson, Bradley S (January 2010). "Normal Development of Brain Circuits". Neuropsychopharmacology. 35 (1): 147–168. doi:10.1038/npp.2009.115. PMC 3055433. PMID 19794405.

- ^ Menon, Vinod (October 2011). "Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 15 (10): 483–506. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2011.08.003. PMID 21908230. S2CID 26653572.

- ^ Menon, Vinod (2017). "Systems neuroscience". In Hopkins, Brian; Barr, Ronald G. (eds.). Cambridge Encyclopedia of Child Development (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ Craighead, W. Edward; Nemeroff, Charles B., eds. (2004). "Neuroethology". The Concise Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology and Behavioral Science. Wiley. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ Solberg Nes, Lise; Segerstrom, Suzanne C. "Psychoneuroimmunology". In Spielberger, Charles Donald (ed.). Encyclopedia of Applied Psychology (1st ed.). Elsevier Science & Technology. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ Kaczmarek, Leonard K; Nadel, L. (2005). "Neuron Doctrine". Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science (1st ed.). Wiley. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ Aragona M, Kotzalidis GD, Puzella A. (2013) The many faces of empathy, between phenomenology and neuroscience Archived 2020-10-02 at the Wayback Machine. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 4:5-12

- ^ Ofengenden, Tzofit (2014). "Memory formation and belief" (PDF). Dialogues in Philosophy, Mental and Neuro Sciences. 7 (2): 34–44.

- ^ Gordon, Ross; Ciorciari, Joseph; Van Laer, Tom (2018). "Using EEG to examine the role of attention, working memory, emotion, and imagination in narrative transportation" (PDF). European Journal of Marketing. 52: 92–117. doi:10.1108/EJM-12-2016-0881. SSRN 2892967.

- ^ "Neurologic Diseases". medlineplus.gov. National Library of Medicine (NIH). Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ "Neurosciences". A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia. Johns Creek (GA): Ebix, inc. 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ IEEE Brain (2019). "Neurotherapy: Treating Disorders by Retraining the Brain". The Future Neural Therapeutics White Paper. Retrieved 23.01.2025 from: https://brain.ieee.org/topics/neurotherapy-treating-disorders-by-retraining-the-brain/#:~:text=Neurotherapy%20trains%20a%20patient's%20brain,wave%20activity%20through%20positive%20reinforcement

- ^ International Neuromodulation Society, Retrieved 23 January 2025 from: https://www.neuromodulation.com/

- ^ Val Danilov I (2023). "The Origin of Natural Neurostimulation: A Narrative Review of Noninvasive Brain Stimulation Techniques." OBM Neurobiology 2024; 8(4): 260; https://doi:10[dead link].21926/obm.neurobiol.2404260.

- ^ Lepage M (2010). "Research at the Brain Imaging Centre". Douglas Mental Health University Institute. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012.

- ^ Gordon E (2003). "Integrative neuroscience". Neuropsychopharmacology. 28 (Suppl 1): S2-8. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300136. PMID 12827137.

- ^ Krucoff, Max O.; Rahimpour, Shervin; Slutzky, Marc W.; Edgerton, V. Reggie; Turner, Dennis A. (27 December 2016). "Enhancing Nervous System Recovery through Neurobiologics, Neural Interface Training, and Neurorehabilitation". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 10: 584. doi:10.3389/fnins.2016.00584. PMC 5186786. PMID 28082858.

- ^ Haselager, Pim; Vlek, Rutger; Hill, Jeremy; Nijboer, Femke (1 November 2009). "A note on ethical aspects of BCI". Neural Networks. 22 (9): 1352–1357. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2009.06.046. hdl:2066/77533. PMID 19616405.

- ^ Nijboer, Femke; Clausen, Jens; Allison, Brendan Z.; Haselager, Pim (2013). "The Asilomar Survey: Stakeholders' Opinions on Ethical Issues Related to Brain–Computer Interfacing". Neuroethics. 6 (3): 541–578. doi:10.1007/s12152-011-9132-6. PMC 3825606. PMID 24273623.

- ^ Panksepp J (1990). "A role for "affective neuroscience" in understanding stress: the case of separation distress circuitry". In Puglisi-Allegra S; Oliverio A (eds.). Psychobiology of Stress. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic. pp. 41–58. ISBN 978-0-7923-0682-5.

- ^ Thomas, Roger K (1993). "INTRODUCTION: A Biopsychology Festschrift in Honor of Lelon J. Peacock". Journal of General Psychology. 120 (1): 5.

- ^ "Cellular neuroscience - Latest research and news". Nature.

- ^ a b c "About Neuroscience".

- ^ "Computational neuroscience - Latest research and news". Nature.

- ^ Chiao, J.Y. & Ambady, N. (2007). Cultural neuroscience: Parsing universality and diversity across levels of analysis. In Kitayama, S. and Cohen, D. (Eds.) Handbook of Cultural Psychology, Guilford Press, New York, pp. 237–254.

- ^ "Developmental Neuroscience | Graduate Program in Neuroscience".

- ^ Eryomin A.L. (2022) Biophysics of Evolution of Intellectual Systems // Biophysics, Vol. 67, No. 2, pp. 320–326.

- ^ Longstaff, Alan; Revest, Patricia (1998). Molecular Neuroscience. Garland Science. ISBN 978-1859962503.

- ^ Pampaloni, Niccolò Paolo; Giugliano, Michele; Scaini, Denis; Ballerini, Laura; Rauti, Rossana (15 January 2019). "Advances in Nano Neuroscience: From Nanomaterials to Nanotools". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 12 953. doi:10.3389/fnins.2018.00953. PMC 6341218. PMID 30697140.

- ^ "Neural Engineering – EMBS". Archived from the original on 2022-06-19. Retrieved 2021-11-11.

- ^ Lyle, Randall R. (2011). "Neuroanatomy". Encyclopedia of Child Behavior and Development. p. 1011. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-79061-9_1946. ISBN 978-0-387-77579-1.

- ^ "Definition of NEUROCHEMISTRY". 19 May 2023.

- ^ Shepherd, Gordon M. (2013-07-16). Neurogastronomy: how the brain creates flavor and why it matters. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-15911-1. OCLC 882238865.

- ^ "Neurogenetics". 2024.

- ^ Zhang, Jue; Chen, Kun; Wang, Di; Gao, Fei; Zheng, Yijia; Yang, Mei (2020). "Editorial: Advances of Neuroimaging and Data Analysis". Frontiers in Neurology. 11 257. doi:10.3389/fneur.2020.00257. PMC 7156609. PMID 32322238.

- ^ "Neuroimmunology - Latest research and news". Nature.

- ^ "Frontiers in Neuroinformatics".

- ^ "Neurolinguistics". Archived from the original on 2022-03-03. Retrieved 2021-11-11.

- ^ "Neurophysics at the ION". 29 January 2018.

- ^ Luhmann, Heiko J. (2013). "Neurophysiology". Encyclopedia of Sciences and Religions. pp. 1497–1500. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-8265-8_779. ISBN 978-1-4020-8264-1.

- ^ Gluck, Mark A.; Mercado, Eduardo; Myers, Catherine E. (2016). Learning and Memory: From Brain to Behavior. New York/NY, USA: Worth Publishers. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-319-15405-9.

- ^ Davis, Kenneth L. (2002). Neuropsychopharmacology: an official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (Fifth ed.). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-4698-7903-1.

- ^ Bruner, Emiliano (2003). "Fossil traces of the human thought: paleoneurology and the evolution of the genus Homo" (PDF). Journal of Anthropological Sciences. 81: 29–56. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2012.

- ^ Cacioppo, John T.; Berntson, Gary G.; Decety, Jean (2010). "Social Neuroscience and ITS Relationship to Social Psychology". Social Cognition. 28 (6): 675–685. doi:10.1521/soco.2010.28.6.675. PMC 3883133. PMID 24409007.

- ^ "Systems Neuroscience".

- ^ "Careers in Neuroscience". neuronline sfn/.

- ^ "Financial and organizational highlights" (PDF). Society for Neuroscience. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 15, 2012.

- ^ "Société des Neurosciences". Neurosciences.asso.fr. 2013-01-24. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ "About Us". Simply Neuroscience. Retrieved 2021-07-14.

- ^ "About Us, Project Encephalon". Project Encephalon. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "International Brain Initiative". 2021-10-15. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ "International Brain Initiative". The Kavli Foundation. Archived from the original on 2020-02-05. Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- ^ "Australian Brain Alliance".

- ^ "Canadian Brain Research Strategy". Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ "Korea Brain Research Institute". Korea Brain Research Institute. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ "Israel Brain Technologies". Archived from the original on 2020-01-28. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ Rommelfanger, Karen S.; Jeong, Sung-Jin; Ema, Arisa; Fukushi, Tamami; Kasai, Kiyoto; Ramos, Khara M.; Salles, Arleen; Singh, Ilina; Amadio, Jordan (2018). "Neuroethics Questions to Guide Ethical Research in the International Brain Initiatives". Neuron. 100 (1): 19–36. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2018.09.021. PMID 30308169.

- ^ "About the International Brain Bee". The International Brain Bee. Archived from the original on 2013-05-10. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ "Brain Facts: A Primer on the Brain and Nervous System". Society for Neuroscience.

- ^ "Neuroscience Core Concepts: The Essential Principles of Neuroscience". Society for Neuroscience. Archived from the original on April 15, 2012.

- ^ "Brain Awareness Week Campaign". The Dana Foundation.

- ^ "Official CIHR Canadian National Brain Bee Website". Archived from the original on May 30, 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ "About FUN". Faculty for Undergraduate Neuroscience. Archived from the original on 2018-08-26. Retrieved 2018-08-26.

- ^ Goswami U (2004). "Neuroscience, education and special education". British Journal of Special Education. 31 (4): 175–183. doi:10.1111/j.0952-3383.2004.00352.x.

- ^ "The SEPA Program". NIH. Archived from the original on September 20, 2011. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ^ "About Education and Human Resources". NSF. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ^ Ham, Donhee; Park, Hongkun; Hwang, Sungwoo; Kim, Kinam (2021). "Neuromorphic electronics based on copying and pasting the brain". Nature Electronics. 4 (9): 635–644. doi:10.1038/s41928-021-00646-1.

- ^ Mead, Carver (1990). "Neuromorphic electronic systems". Proceedings of the IEEE. 78 (10): 1629–1636. Bibcode:1990IEEEP..78.1629M. doi:10.1109/5.58356.

- ^ Hylton, Todd. "Introduction to Neuromorphic Computing Insights and Challenges" (PDF). Brain Corporation.

- ^ Calimera, A; Macii, E; Poncino, M (July 2013). "The Human Brain Project and neuromorphic computing". Functional Neurology. 28 (3): 191–6. PMC 3812737. PMID 24139655.

- ^ "Beyond von Neumann, Neuromorphic Computing Steadily Advances". HPCwire. 2016-03-21. Retrieved 2021-10-08.

- ^ "Bionic neurons could enable implants to restore failing brain circuits | Neuroscience". The Guardian. 2019-12-03. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ "Scientists Create Artificial Neuron That Retains Electronic Memories". Interestingengineering.com. 2021-08-06. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1904". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1906". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1911". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1914". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1932". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1936". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1938". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1944". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ a b "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1949". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1955". Nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 25 December 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1957". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1961". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ a b "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1970". Nobel Foundation.

- ^ a b c "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1981". Nobel Foundation.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1973". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 19 August 2007. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1977". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1986". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1991". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1997". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 10 October 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1997". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2000". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2003". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2004". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 19 August 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2012". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 13 October 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2014". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2017". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2021". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2024". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Bear, M. F.; B. W. Connors; M. A. Paradiso (2006). Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott. ISBN 978-0-7817-6003-4.Binder, Marc D.; Hirokawa, Nobutaka; Windhorst, Uwe, eds. (2009). Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-23735-8.

- Kandel, ER; Schwartz JH; Jessell TM (2012). Principles of Neural Science (5th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-8385-7701-1.

- Squire, L. et al. (2012). Fundamental Neuroscience, 4th edition. Academic Press; ISBN 0-12-660303-0

- Byrne and Roberts (2004). From Molecules to Networks. Academic Press; ISBN 0-12-148660-5

- Sanes, Reh, Harris (2005). Development of the Nervous System, 2nd edition. Academic Press; ISBN 0-12-618621-9

- Siegel et al. (2005). Basic Neurochemistry, 7th edition. Academic Press; ISBN 0-12-088397-X

- Rieke, F. et al. (1999). Spikes: Exploring the Neural Code. The MIT Press; Reprint edition ISBN 0-262-68108-0

- section.47 Neuroscience 2nd ed. Dale Purves, George J. Augustine, David Fitzpatrick, Lawrence C. Katz, Anthony-Samuel LaMantia, James O. McNamara, S. Mark Williams. Published by Sinauer Associates, Inc., 2001.

- section.18 Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular, and Medical Aspects 6th ed. by George J. Siegel, Bernard W. Agranoff, R. Wayne Albers, Stephen K. Fisher, Michael D. Uhler, editors. Published by Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 1999.

- Andreasen, Nancy C. (March 4, 2004). Brave New Brain: Conquering Mental Illness in the Era of the Genome. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514509-0.

- Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York, Avon Books. ISBN 0-399-13894-3 (Hardcover) ISBN 0-380-72647-5 (Paperback)

- Gardner, H. (1976). The Shattered Mind: The Person After Brain Damage. New York, Vintage Books, 1976 ISBN 0-394-71946-8

- Goldstein, K. (2000). The Organism. New York, Zone Books. ISBN 0-942299-96-5 (Hardcover) ISBN 0-942299-97-3 (Paperback)

- Lauwereyns, Jan (February 2010). The Anatomy of Bias: How Neural Circuits Weigh the Options (PDF). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-12310-5.

- Subhash Kak, The Architecture of Knowledge: Quantum Mechanics, Neuroscience, Computers and Consciousness, Motilal Banarsidass, 2004, ISBN 81-87586-12-5

- Llinas R. (2001). I of the vortex: from neurons to self MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-12233-2 (Hardcover) ISBN 0-262-62163-0 (Paperback)

- Luria, A. R. (1997). The Man with a Shattered World: The History of a Brain Wound. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-224-00792-0 (Hardcover) ISBN 0-674-54625-3 (Paperback)

- Luria, A. R. (1998). The Mind of a Mnemonist: A Little Book About A Vast Memory. New York, Basic Books, Inc. ISBN 0-674-57622-5

- Medina, J. (2008). Brain Rules: 12 Principles for Surviving and Thriving at Work, Home, and School. Seattle, Pear Press. ISBN 0-9797777-0-4 (Hardcover with DVD)

- Pinker, S. (1999). How the Mind Works. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-31848-6

- Pinker, S. (2002). The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. Viking Adult. ISBN 0-670-03151-8

- Robinson, D. L. (2009). Brain, Mind and Behaviour: A New Perspective on Human Nature (2nd ed.). Dundalk, Ireland: Pontoon Publications. ISBN 978-0-9561812-0-6.

- Penrose, R., Hameroff, S. R., Kak, S., & Tao, L. (2011). Consciousness and the universe: Quantum physics, evolution, brain & mind. Cambridge, MA: Cosmology Science Publishers.

- Ramachandran, V. S. (1998). Phantoms in the Brain. New York, HarperCollins. ISBN 0-688-15247-3 (Paperback)

- Rose, S. (2006). 21st Century Brain: Explaining, Mending & Manipulating the Mind ISBN 0-09-942977-2 (Paperback)

- Sacks, O. The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. Summit Books ISBN 0-671-55471-9 (Hardcover) ISBN 0-06-097079-0 (Paperback)

- Sacks, O. (1990). Awakenings. New York, Vintage Books. (See also Oliver Sacks) ISBN 0-671-64834-9 (Hardcover) ISBN 0-06-097368-4 (Paperback)

- Encyclopedia:Neuroscience Archived 2020-02-22 at the Wayback Machine Scholarpedia Expert articles

- Sternberg, E. (2007) Are You a Machine? The Brain, the Mind and What it Means to be Human. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books.

- Churchland, P. S. (2011) Braintrust: What Neuroscience Tells Us about Morality Archived 2020-11-12 at the Wayback Machine. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-13703-X

- Selvin, Paul (2014). "Hot Topics presentation: New Small Quantum Dots for Neuroscience". SPIE Newsroom. doi:10.1117/2.3201403.17.

External links

[edit]- Neuroscience on In Our Time at the BBC

- Neuroscience Information Framework (NIF)

- American Society for Neurochemistry

- British Neuroscience Association (BNA)

- Federation of European Neuroscience Societies

- Neuroscience Online (electronic neuroscience textbook)

- HHMI Neuroscience lecture series - Making Your Mind: Molecules, Motion, and Memory Archived 2013-06-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Société des Neurosciences

- Neuroscience For Kids