Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

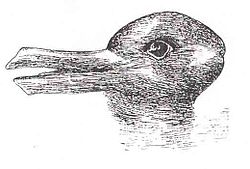

Ambiguous image

View on Wikipedia

Ambiguous images or reversible figures are visual forms that create ambiguity by exploiting graphical similarities and other properties of visual system interpretation between two or more distinct image forms. These are famous for inducing the phenomenon of multistable perception. Multistable perception is the occurrence of an image being able to provide multiple, although stable, perceptions.

One of the earliest examples of this type is the rabbit–duck illusion, first published in Fliegende Blätter, a German humor magazine.[1] Other classic examples are the Rubin vase,[2] and the "My Wife and My Mother-in-Law" drawing, the latter dating from a German postcard of 1888.

Ambiguous images are important to the field of psychology because they are often research tools used in experiments.[3] There is varying evidence on whether ambiguous images can be represented mentally,[4] but a majority of research has theorized that mental images cannot be ambiguous.[5]

Identifying and resolving ambiguous images

[edit]

Middle vision is the stage in visual processing that combines all the basic features in the scene into distinct, recognizable object groups. This stage of vision comes before high-level vision (understanding the scene) and after early vision (determining the basic features of an image). When perceiving and recognizing images, mid-level vision comes into use when we need to classify the object we are seeing quickly. Whether perceived or actual, Negative space will play a role here.

Higher-level vision is used when the object classified must now be recognized as a specific member of its group. For example, through mid-level vision we perceive a face, then through high-level vision we recognize a face of a familiar person. Mid-level vision and high-level vision are crucial for understanding a reality that is filled with ambiguous perceptual inputs.[6]

Perceiving the image in mid-level vision

[edit]

When we see an image, the first thing we do is attempt to organize all the parts of the scene into different groups.[8] To do this, one of the most basic methods used is finding the edges. Edges can include obvious perceptions such as the edge of a house, and can include other perceptions that the brain needs to process deeper, such as the edges of a person's facial features. When finding edges, the brain's visual system detects a point on the image with a sharp contrast of lighting. Being able to detect the location of the edge of an object aids in recognizing the object. In ambiguous images, detecting edges still seems natural to the person perceiving the image. However, the brain undergoes deeper processing to resolve the ambiguity. For example, consider an image that involves an opposite change in magnitude of luminance between the object and the background (e.g. From the top, the background shifts from black to white, and the object shifts from white to black). The opposing gradients will eventually come to a point where there is an equal degree of luminance of the object and the background. At this point, there is no edge to be perceived. To counter this, the visual system connects the image as a whole rather than a set of edges, allowing one to see an object rather than edges and non-edges. Although there is no complete image to be seen, the brain is able to accomplish this because of its understanding of the physical world and real incidents of ambiguous lighting.[6]

In ambiguous images, an illusion is often produced from illusory contours. An illusory contour is a perceived contour without the presence of a physical gradient. In examples where a white shape appears to occlude black objects on a white background, the white shape appears to be brighter than the background, and the edges of this shape produce the illusory contours.[9] These illusory contours are processed by the brain in a similar way as real contours.[8] The visual system accomplishes this by making inferences beyond the information that is presented in much the same way as the luminance gradient.

Gestalt grouping rules

[edit]

In mid-level vision, the visual system utilizes a set of heuristic methods, called Gestalt grouping rules, to quickly identify a basic perception of an object that helps to resolve an ambiguity.[3] This allows perception to be fast and easy by observing patterns and familiar images rather than a slow process of identifying each part of a group. This aids in resolving ambiguous images because the visual system will accept small variations in the pattern and still perceive the pattern as a whole. The Gestalt grouping rules are the result of the experience of the visual system. Once a pattern is perceived frequently, it is stored in memory and can be perceived again easily without the requirement of examining the entire object again.[6] For example, when looking at a chess board, we perceive a checker pattern and not a set of alternating black and white squares.

Good continuation

[edit]The principle of good continuation provides the visual system a basis for identifying continuing edges. This means that when a set of lines is perceived, there is a tendency for a line to continue in one direction. This allows the visual system to identify the edges of a complex image by identifying points where lines cross. For example, two lines crossed in an "X" shape will be perceived as two lines travelling diagonally rather than two lines changing direction to form "V" shapes opposite to each other. An example of an ambiguous image would be two curving lines intersecting at a point. This junction would be perceived the same way as the "X", where the intersection is seen as the lines crossing rather than turning away from each other. Illusions of good continuation are often used by magicians to trick audiences.[10]

Similarity

[edit]The rule of similarity states that images that are similar to each other can be grouped together as being the same type of object or part of the same object. Therefore, the more similar two images or objects are, the more likely it will be that they can be grouped together. For example, two squares among many circles will be grouped together. They can vary in similarity of colour, size, orientation and other properties, but will ultimately be grouped together with varying degrees of membership.[6]

Proximity, common region, and connectedness

[edit]

The grouping property of proximity (Gestalt) is the spatial distance between two objects. The closer two objects are, the more likely they belong to the same group. This perception can be ambiguous without the person perceiving it as ambiguous. For example, two objects with varying distances and orientations from the viewer may appear to be proximal to each other, while a third object may be closer to one of the other objects but appear farther.

Objects occupying a common region on the image appear to already be members of the same group. This can include unique spatial location, such as two objects occupying a distinct region of space outside of their group's own. Objects can have close proximity but appear as though part of a distinct group through various visual aids such as a threshold of colours separating the two objects.

Additionally, objects can be visually connected in ways such as drawing a line going from each object. These similar but hierarchical rules suggest that some Gestalt rules can override other rules.[6]

≥°==Texture segmentation and figure-ground assignments== The visual system can also aid itself in resolving ambiguities by detecting the pattern of texture in an image. This is accomplished by using many of the Gestalt principles. The texture can provide information that helps to distinguish whole objects, and the changing texture in an image reveals which distinct objects may be part of the same group. Texture segmentation rules often both cooperate and compete with each other, and examining the texture can yield information about the layers of the image, disambiguating the background, foreground, and the object.[11]

Size and surroundedness

[edit]When a region of texture completely surrounds another region of texture, it is likely the background. Additionally, the smaller regions of texture in an image are likely the figure.[6]

Parallelism and symmetry

[edit]Parallelism is another way to disambiguate the figure of an image. The orientation of the contours of different textures in an image can determine which objects are grouped together. Generally, parallel contours suggest membership to the same object or group of objects. Similarly, symmetry of the contours can also define the figure of an image.[6]

Extremal edges and relative motion

[edit]

An extremal edge is a change in texture that suggests an object is in front of or behind another object. This can be due to a shading effect on the edges of one region of texture, giving the appearance of depth. Some extremal edge effects can overwhelm the segmentations of surroundedness or size. The edges perceived can also aid in distinguishing objects by examining the change in texture against an edge due to motion.[6]

Using ambiguous images to hide in the real world: camouflage

[edit]In nature, camouflage is used by organisms to escape predators. This is achieved through creating an ambiguity of texture segmentation by imitating the surrounding environment. Without being able to perceive noticeable differences in texture and position, a predator will be unable to see their prey.[6]

Occlusion

[edit]Many ambiguous images are produced through some occlusion, wherein an object's texture suddenly stops. An occlusion is the visual perception of one object being behind or in front of another object, providing information about the order of the layers of texture.[6] The illusion of occlusion is apparent in the effect of illusory contours, where occlusion is perceived despite being non-existent. Here, an ambiguous image is perceived to be an instance of occlusion. When an object is occluded, the visual system only has information about the parts of the object that can be seen, so the rest of the processing must be done deeper and must involve memory.

Accidental viewpoints

[edit]An accidental viewpoint is a single visual position that produces an ambiguous image. The accidental viewpoint does not provide enough information to distinguish what the object is.[12] Often, this image is perceived incorrectly and produces an illusion that differs from reality. For example, an image may be split in half, with the top half being enlarged and placed further away from the perceiver in space. This image will be perceived as one complete image from only a single viewpoint in space, rather than the reality of two separate halves of an object, creating an optical illusion. Street artists often use tricks of point-of-view to create two-dimensional scenes on the ground that appear three-dimensional.

Recognizing an object through high-level vision

[edit]

Figures drawn in a way that avoids depth cues may become ambiguous. Classic examples of this phenomenon are the Necker cube,[6] and the rhombille tiling (viewed as an isometric drawing of cubes).

To go further than just perceiving the object is to recognize the object. Recognizing an object plays a crucial role in resolving ambiguous images, and relies heavily on memory and prior knowledge. To recognize an object, the visual system detects familiar components of it, and compares the perceptual representation of it with a representation of the object stored in memory.[8] This can be done using various templates of an object, such as "dog" to represent dogs in general. The template method is not always successful because members of a group may significantly differ visually from each other, and may look much different if viewed from different angles. To counter the problem of viewpoint, the visual system detects familiar components of an object in 3-dimensional space. If the components of an object perceived are in the same position and orientation of an object in memory, recognition is possible.[6] Research has shown that people that are more creative in their imagery are better able to resolve ambiguous images. This may be due to their ability to quickly identify patterns in the image.[13] When making a mental representation of an ambiguous image, in the same way as normal images, each part is defined and then put onto the mental representation. The more complex the scene is, the longer it takes to process and add to the representation.[14]

Using memory and recent experience

[edit]Our memory has a large impact on resolving an ambiguous image, as it helps the visual system to identify and recognize objects without having to analyze and categorize them repeatedly. Without memory and prior knowledge, an image with several groups of similar objects will be difficult to perceive. Any object can have an ambiguous representation and can be mistakenly categorized into the wrong groups without sufficient memory recognition of an object. This finding suggests that prior experience is necessary for proper perception.[15] Studies have been done with the use of Greebles to show the role of memory in object recognition.[6] The act of priming the participant with an exposure to a similar visual stimulus also has a large effect on the ease of resolving an ambiguity.[15]

Disorders in perception

[edit]Prosopagnosia is a disorder that causes a person to be unable to identify faces. The visual system undergoes mid-level vision and identifies a face, but high-level vision fails to identify who the face belongs to. In this case, the visual system identifies an ambiguous object, a face, but is unable to resolve the ambiguity using memory, leaving the affected unable to determine who they are seeing.[6]

In media

[edit]From 1903 to 1905 Gustave Verbeek wrote his comic series The Upside Downs of Little Lady Lovekins and Old Man Muffaroo. These comics were made in such a way that one could read the 6-panel comic, flip the book and keep reading. He made 64 such comics in total. In 2012 a remake of a selection of the comics was made by Marcus Ivarsson in the book 'In Uppåner med Lilla Lisen & Gamle Muppen'. (ISBN 978-91-7089-524-1)

The use of the ambiguous image phenomena can be seen in select works of M.C. Escher and Salvador Dalí. The children's book, Round Trip, by Ann Jonas used ambiguous images in the illustrations, where the reader could read the book front to back normally at first, and then flip it upside down to continue the story and see the pictures in a new perspective.[16]

Gallery

[edit]-

Reversible Head with Basket of Fruit, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, 1590

-

French caricature of Napoleon III, 1870

-

Comics The Upside Downs of Little Lady Lovekins and Old Man Muffaroo - At the house of the writing pig by Gustave Verbeek containing ambigram sentences, 1904

-

Drawing of reversible female face by Rex Whistler, with ambigram ¡OHO!. 180° rotational symmetry. The face of a young woman changes into a grandmother. Published in 1946.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Fliegende Blätter Oct. 23, 1892, p. 147

- ^ Parkkonen, L.; Andersson, J.; Hämäläinen, M.; Hari, R. (2008). "Early visual brain areas reflect the percept of an ambiguous scene". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (51): 20500–20504. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10520500P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810966105. PMC 2602606. PMID 19074267.

- ^ a b Wimmer, M.; Doherty, M. (2011). "The development of ambiguous figure perception: Vi. conception and perception of ambiguous figures". Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 76 (1): 87–104. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5834.2011.00595.x.

- ^ Mast, F.W.; Kosslyn, S.M. (2002). "Visual mental images can be ambiguous: Insights from individual differences in spatial transformation abilities". Cognition. 86 (1): 57–70. doi:10.1016/S0010-0277(02)00137-3. PMID 12208651. S2CID 37046301.

- ^ Chambers, D.; Reisberg, D. (1985). "Can mental images be ambiguous?". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 11 (3): 317–328. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.11.3.317. S2CID 197655523.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Wolfe, J., Kluender, K., & Levi, D. (2009). Sensation and perception. (2 ed.). Sunderland: Sinauer Associates.[page needed]

- ^ Postic, Guillaume; Ghouzam, Yassine; Chebrek, Romain; Gelly, Jean-Christophe (2017). "An ambiguity principle for assigning protein structural domains". Science Advances. 3 (1) e1600552. Bibcode:2017SciA....3E0552P. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1600552. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 5235333. PMID 28097215.

- ^ a b c Halko, Mark Anthony (2008). Illusory contour and surface completion mechanisms in human visual cortex (Thesis). ProQuest 621754807.

- ^ Bradley, D.R.; Dumais, S.T. (1975). "Ambiguous cognitive contours". Nature. 257 (5527): 582–584. Bibcode:1975Natur.257..582B. doi:10.1038/257582a0. PMID 1165783. S2CID 4295897.

- ^ Bamhart, A.S. (2010). "The exploitation of gestalt principles by magicians". Perception. 39 (9): 1286–1289. doi:10.1068/p6766. PMID 21125955. S2CID 8016846.

- ^ Tang, Xiangyu (2005). A model for figure-ground segmentation by self-organized cue integration (Thesis). University of Southern California Digital Library (USC.DL). doi:10.25549/usctheses-c16-597264. ProQuest 621577763.

- ^ Koning, A.; van Lier, R. (2006). "No symmetry advantage when object matching involves accidental viewpoints". Psychological Research. 70 (1): 52–58. doi:10.1007/s00426-004-0191-8. hdl:2066/55694. PMID 15480756. S2CID 35284032.

- ^ Riquelme, H (2002). "Can people creative in imagery interpret ambiguous figures faster than people less creative in imagery?". The Journal of Creative Behavior. 36 (2): 105–116. doi:10.1002/j.2162-6057.2002.tb01059.x.

- ^ Kosslyn, S.M.; Reiser, B.J.; Farah, M.J.; Fliegel, S.L. (1983). "Generating visual images: Units and relations". Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 112 (2): 278–303. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.112.2.278. PMID 6223974.

- ^ a b Daelli, V.; van Rijsbergen, N.J.; Treves, A. (2010). "How recent experience affects the perception of ambiguous objects". Brain Research. 1322: 81–91. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2010.01.060. PMID 20122901. S2CID 45388116.

- ^ Higgins, Carter (29 May 2013). "Round Trip – Design Of The Picture Book". Design of the Picture Book. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

.svg/232px-My_Wife_and_My_Mother-In-Law_(Hill).svg.png)

.svg/1449px-My_Wife_and_My_Mother-In-Law_(Hill).svg.png)