Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

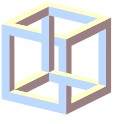

Impossible cube

View on Wikipedia

The impossible cube or irrational cube is an impossible object invented by M.C. Escher for his 1958 print Belvedere. It is a two-dimensional figure that superficially resembles a perspective drawing of a three-dimensional cube, with its features drawn inconsistently from the way they would appear in an actual cube.

Usage in art

[edit]In Escher's Belvedere a man seated at the foot of a building holds an impossible cube. A drawing of the related Necker cube (with its crossings circled) lies at his feet, while the building itself shares some of the same impossible features as the cube.[1][2] Another Escher print, Man with Cuboid, shows the same man and impossible cube, without the Necker cube drawing.[3] In Escher's version, the beams in the top half of the drawing are drawn as if viewed from above, with a crossing consistent with that point of view, while the beams in the bottom half are drawn as if viewed from below, again with a crossing consistent with that point of view.[4] This internal consistency of the top and bottom halves of the drawing is a reflection of the impossible tower that forms the main subject of Escher's print, whose interlaced pillars again look consistent if one views only a single floor at a time.[5]

Other artists than Escher, including Jos De Mey, have also made artworks featuring an impossible cube.[3] A doctored photograph purporting to be of an impossible cube was published in the June 1966 issue of Scientific American, where it was called a "Freemish crate".[6][7] An impossible cube has also been featured on an Austrian postage stamp, honoring the 10th Congress of the Austrian Mathematical Society in Innsbruck in 1981.[8] The Austrian stamp shows Escher's version, but some of these alternative versions draw all beams with a single viewpoint from above, reversing one or both of the crossings of the Necker cube from the way the beams of a standard cube would cross with that viewpoint.[9]

Explanation

[edit]

The impossible cube draws upon the ambiguity present in a Necker cube illustration, in which a cube is drawn with its edges as line segments, and can be interpreted as being in either of two different three-dimensional orientations.

The apparent solidity of the beams gives the impossible cube greater visual ambiguity than the Necker cube, which is less likely to be perceived as an impossible object. The illusion plays on the human eye's interpretation of two-dimensional pictures as three-dimensional objects. It is possible for three-dimensional objects to have the visual appearance of the impossible cube when seen from certain angles, either by making carefully placed cuts in the supposedly solid beams or by using forced perspective, but human experience with right-angled objects makes the impossible appearance seem more likely than the reality.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ernst, Bruno (2003), "Selection is Distortion", in Schattschneider, D.; Emmer, M. (eds.), M. C. Escher's Legacy: A Centennial Celebration, Berlin: Springer, pp. 5–16, ISBN 3-540-42458-X

- ^ Barrow, John D. (1999), Impossibility: The Limits of Science and the Science of Limits, Oxford University Press, p. 14, ISBN 0-19-513082-0

- ^ a b De Mey, Jos (2003), "Painting After M. C. Escher", in Schattschneider, D.; Emmer, M. (eds.), M. C. Escher's Legacy: A Centennial Celebration, Springer, pp. 130–141

- ^ Escher, Maurits Cornelis (2000), M. C. Escher: The Graphic Work, Cologne: Taschen, p. 15, ISBN 3-8228-5864-1

- ^ Prickett, Stephen (December 1972), "Dante, Beatrice, and M. C. Escher: Disconfirmation as a metaphor", Journal of European Studies, 2 (4): 333–354, doi:10.1177/004724417200200401; see p. 347

- ^ a b Smith, Nancy E. (1984), "A new angle on the freemish crate", Perception, 13 (2): 153–154, doi:10.1068/p130153, PMID 6504675

- ^ Cochran, C. F. (June 1966), "Letters", Scientific American, 214 (6): 8, Bibcode:1966SciAm.214f...8., doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0666-8, JSTOR 24930957

- ^ Wilson, Robin J. (2001), Stamping Through Mathematics, Springer, p. 102, ISBN 0-387-98949-8

- ^ Thro, E. Broydrick (December 1983), "Distinguishing two classes of impossible objects", Perception, 12 (6), SAGE Publications: 733–751, doi:10.1068/p120733, PMID 6678416; see pp. 742–743