Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

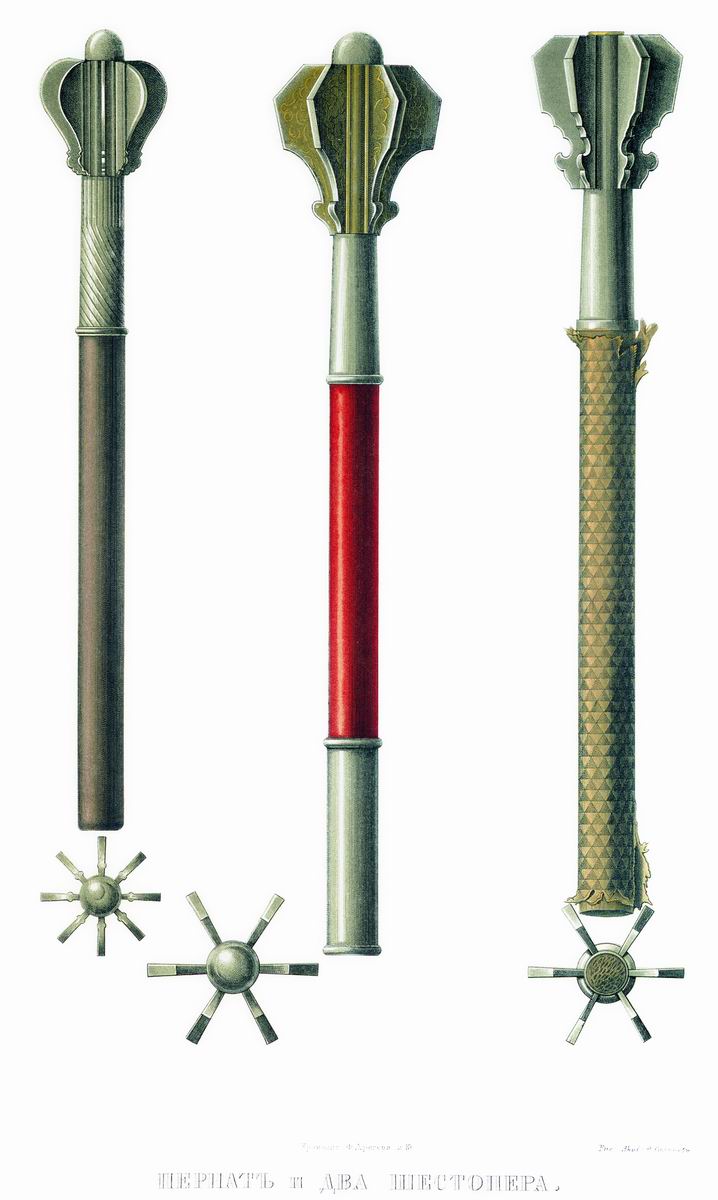

Pernach

View on Wikipedia

A pernach (Russian: перна́ч, Ukrainian: перна́ч or пірна́ч, pirnach, Polish: piernacz) is a type of flanged mace originating in the 12th century in the region of Kievan Rus' and later widely used throughout Europe. The name comes from the Slavic word перо (pero) meaning feather, referring to a type of mace resembling an arrow with feathering.

Uses against armour and mail

[edit]Among a variety of similar weapons developed in 12th-century Persian- and Turkic-dominated areas, the pernach became pre-eminent,[1] being capable of penetrating plate armour and plate mail.

Ceremonial uses

[edit]A pernach or shestoper (Russian: шестопeр, "six-feathered") was often carried as a ceremonial mace of rank by certain Eastern European military commanders, including Polish magnates, Ukrainian Cossack colonels and sotniks (cf. centurion).

Symbolic uses

[edit]In Ukraine, it symbolized the authority of polkovnyks (regional leaders or military officers)[2] unlike another mace, the bulawa, which was associated with the Hetman.

References

[edit]- ^ Caza, Shawn M. Medieval flanged maces

- ^ Pernach. Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine.