Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dynamics (music)

View on Wikipedia

In music, the dynamics of a piece are the variation in loudness between notes or phrases. Dynamics are indicated by specific musical notation, often in some detail. However, dynamics markings require interpretation by the performer depending on the musical context: a specific marking may correspond to a different volume between pieces or even sections of one piece. The execution of dynamics also extends beyond loudness to include changes in timbre and sometimes tempo rubato.

Purpose and interpretation

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2023) |

Dynamics are one of the expressive elements of music. Used effectively, dynamics help musicians sustain variety and interest in a musical performance, and communicate a particular emotional state or feeling.

Dynamic markings are always relative.[1] p (piano - "soft") never indicates a precise level of loudness; it merely indicates that music in a passage so marked should be considerably quieter than f (forte - "loud"). There are many factors affecting the interpretation of a dynamic marking. For instance, the middle of a musical phrase will normally be played louder than the beginning or end, to ensure the phrase is properly shaped, even where a passage is marked p throughout. Similarly, in multi-part music, some voices will naturally be played louder than others, for instance, to emphasize the melody and the bass line, even if a whole passage is marked at one dynamic level. Some instruments are naturally louder than others – for instance, a tuba playing mezzo-piano will likely be louder than a guitar playing forte, while a high-pitched instrument like the piccolo playing in its upper register can sound loud even when its actual decibel level is lower than that of other instruments.

Dynamic markings

[edit]| Name | Letters | Level |

|---|---|---|

fortissississimo

|

ffff | as loud and strong as possible |

fortississimo

|

fff | very, very loud |

fortissimo

|

ff | very loud |

forte

|

f | loud |

mezzo-forte

|

mf | moderately loud |

mezzo-piano

|

mp | moderately quiet |

piano

|

p | quiet |

pianissimo

|

pp | very quiet |

pianississimo

|

ppp | very very quiet |

The two basic dynamic indications in music are:

More subtle degrees of loudness or softness are indicated by:

- mp, standing for mezzo-piano, meaning "moderately quiet"

- mf, standing for mezzo-forte, meaning "moderately loud"[6]

- più p, standing for più piano and meaning "quieter"

- più f, standing for più forte and meaning "louder"

Use of up to four consecutive fs or three consecutive ps is also common:

- pp, standing for pianissimo and meaning "very quiet"

- ff, standing for fortissimo and meaning "very loud"

- ppp ("triple piano"), standing for pianississimo or piano pianissimo and meaning "very very quiet"

- fff ("triple forte"), standing for fortississimo or forte fortissimo and meaning "very very loud"

- ffff, standing for fortissississimo and meaning "as loud and strong as possible"

There are additional special markings that are not very common:

- sfz or sf, standing for sforzando and meaning "suddenly very loud", which only applies to a given beat

- rfz or rf, standing for rinforzando and meaning "reinforced", which refers to a sudden increase in volume that only applies to a given phrase

- n or ø, standing for niente and meaning "nothing", which refers to silence; generally used in combination with other markings for special effect

Changes

[edit]

Three Italian words are used to show gradual changes in volume:

- crescendo (abbreviated cresc.) translates as "increasing" (literally "growing")

- decrescendo (abbreviated to decresc.) translates as "decreasing"

- diminuendo (abbreviated dim.) translates as "diminishing"

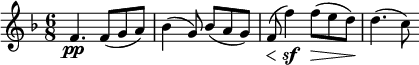

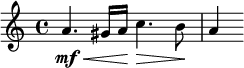

Dynamic changes can be indicated by angled symbols. A crescendo symbol consists of two lines that open to the right (![]() ); a decrescendo symbol starts open on the left and closes toward the right (

); a decrescendo symbol starts open on the left and closes toward the right (![]() ). These symbols are sometimes referred to as hairpins or wedges.[7] The following notation indicates music starting moderately strong, then becoming gradually stronger and then gradually quieter:

). These symbols are sometimes referred to as hairpins or wedges.[7] The following notation indicates music starting moderately strong, then becoming gradually stronger and then gradually quieter:

Hairpins are typically positioned below the staff (or between the two staves in a grand staff), though they may appear above, especially in vocal music or when a single performer plays multiple melody lines. They denote dynamic changes over a short duration (up to a few bars), whereas cresc., decresc., and dim. signify more gradual changes. Word directions can be extended with dashes to indicate the temporal span of the change, which can extend across multiple pages. The term morendo ("dying") may also denote a gradual reduction in both dynamics and tempo.

For pronounced dynamic shifts, cresc. molto and dim. molto are commonly used, with molto meaning "much". Conversely, poco cresc. and poco dim. indicate gentler changes, with "poco" translating to a little, or alternatively poco a poco meaning "little by little".

Sudden dynamic changes are often indicated by prefixing or suffixing subito (meaning "suddenly") to the new dynamic notation. Subito piano (abbreviated as sub. p or p sub.) ("suddenly soft") implies a quick, almost abrupt reduction in volume to around the p range, often employed to subvert listener expectations, signaling a more intimate expression. Likewise, subito can mark sudden increases in volume, as in sub. f or f sub.) ("suddenly loud").

Accented notes are generally marked with an accent sign > placed above or below the note, emphasizing the attack relative to the prevailing dynamics. A sharper and briefer emphasis is denoted with a marcato mark ^ above the note. If a specific emphasis is required, variations of forzando/forzato, or fortepiano can be used.

forzando/forzato signifies a forceful accent, abbreviated as fz. To enhance the effect, subito often precedes it as sfz (subito forzato/forzando, sforzando/sforzato). The interpretation and execution of these markings are at the performer's discretion, with forzato/forzando typically seen as a variation of marcato and subito forzando/forzato as a marcato with added tenuto.[8]

The fortepiano notation fp denotes a forte followed immediately by piano. Contrastingly, pf abbreviates poco forte, translating to "a little loud", but according to Brahms, implies a forte character with a piano sound, although rarely used due to potential confusion with pianoforte.[9]

Messa di voce is a singing technique and musical ornament on a single pitch while executing a crescendo and diminuendo.

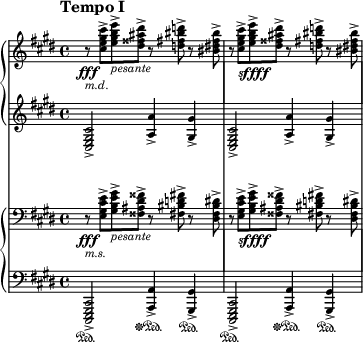

Extreme dynamic markings

[edit]

While the typical range of dynamic markings is from ppp to ffff, some pieces use additional markings of further emphasis. Extreme dynamic markings imply either a very large dynamic range or very small differences of loudness within a normal range. This kind of usage is most common in orchestral works from the late 1800s onward. Generally, these markings are supported by the orchestration of the work, with heavy forte passages brought to life by having many loud instruments like brass and percussion playing at once.

- In Holst's The Planets, ffff occurs twice in "Mars" and once in "Uranus", often punctuated by organ.[10]

- In Stravinsky's The Firebird Suite, ffff is marked for the strings and woodwinds at the end of the Finale.

- Tchaikovsky marks a bassoon solo pppppp (6 ps) in his Pathétique Symphony[11] and uses ffff in passages of his 1812 Overture[12] and his Fifth Symphony.[13][14]

- The baritone passage "Era la notte" from Verdi's opera Otello uses pppp, though the same spot is marked ppp in the full score.[15]

- Sergei Rachmaninoff uses sffff in his Prelude in C♯, Op. 3 No. 2.[16]

- Gustav Mahler, in the third movement of his Seventh Symphony, gives the celli and basses a marking of fffff (5 fs), along with a footnote directing 'pluck so hard that the strings hit the wood'.[a][17]

- On the other extreme, Carl Nielsen, in the second movement of his Fifth Symphony, marked a passage for woodwinds a diminuendo to ppppp (5 ps).[18]΄

- Brian Ferneyhough, in his Lemma-Icon-Epigram, uses ffffff (6 fs).[19]

- Giuseppe Verdi, in Scene 5 (Act II from his opera Otello), uses ppppppp (7 ps).[20]

- György Ligeti uses extreme dynamics in his music: the Cello Concerto begins with a passage marked pppppppp (8 ps),[21] in his Piano Études Étude No. 9 (Vertige) ends with a diminuendo to pppppppp (8 ps),[22] while Étude No. 13 (L'Escalier du Diable) contains a passage marked ffffff (6 fs) that progresses to a ffffffff (8 fs)[23] and his opera Le Grand Macabre has ffffffffff (10 fs) with a stroke of the hammer.

History

[edit]On Music, one of the Moralia attributed to the philosopher Plutarch in the first century AD, suggests that ancient Greek musical performance included dynamic transitions – though dynamics receive far less attention in the text than does rhythm or harmony.

The Renaissance composer Giovanni Gabrieli was one of the first to indicate dynamics in music notation. However, much of the use of dynamics in early Baroque music remained implicit and was achieved through a practice called raddoppio ("doubling") and later ripieno ("filling"), which consisted of creating a contrast between a small number of elements and then a larger number of elements (usually in a ratio of 2:1 or more) to increase the mass of sound. This practice was pivotal to the structuring of instrumental forms such as the concerto grosso and the solo concerto, where a few or one instrument, supported by harmonic basso continuo instruments (organ, lute, theorbo, harpsichord, lirone, and low register strings, such as cello or viola da gamba, often used together) variously alternate or join to create greater contrasts. This practice is usually called terraced dynamics, i.e. the alternation of piano and forte.

Later baroque musicians, such as Antonio Vivaldi, tended to use more varied dynamics. J.S. Bach used some dynamic terms, including forte, piano, più piano, and pianissimo (although written out as full words), and in some cases it may be that ppp was considered to mean pianissimo in this period. In 1752, Johann Joachim Quantz wrote that "Light and shade must be constantly introduced ... by the incessant interchange of loud and soft."[24] In addition to this, the harpsichord in fact becomes louder or softer depending on the thickness of the musical texture (four notes are louder than two).

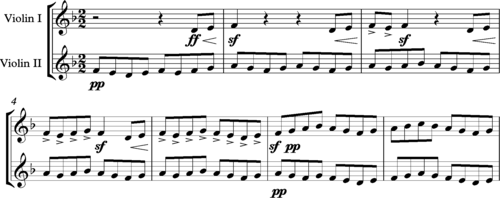

In the Romantic period, composers greatly expanded the vocabulary for describing dynamic changes in their scores. Where Haydn and Mozart specified six levels (pp to ff), Beethoven used also ppp and fff (the latter less frequently), and Brahms used a range of terms to describe the dynamics he wanted. In the slow movement of Brahms's trio for violin, horn and piano (Opus 40), he uses the expressions ppp, molto piano, and quasi niente to express different qualities of quiet. Many Romantic and later composers added più p and più f, making for a total of ten levels between ppp and fff.

An example of how effective contrasting dynamics can be may be found in the overture to Smetana’s opera The Bartered Bride. The fast scurrying quavers played pianissimo by the second violins form a sharply differentiated background to the incisive thematic statement played fortissimo by the firsts.

Interpretation by notation programs

[edit]

In some music notation programs, there are default MIDI key velocity values associated with these indications, but more sophisticated programs allow users to change these as needed. These defaults are listed in the following table for some applications, including Apple's Logic Pro 9 (2009–2013), Avid's Sibelius 5 (2007–2009), musescore.org's MuseScore 3.0 (2019), MakeMusic's Finale 26 (2018-2021), and Musitek's SmartScore X2 Pro (2016) and 64 Pro. (2021). MIDI specifies the range of key velocities as an integer between 0 and 127:

| Symbols | ppppp | pppp | ppp | pp | p | mp | mf | f | ff | fff | ffff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logic Pro 9 dynamics[25] | 16 | 32 | 48 | 64 | 80 | 96 | 112 | 127 | |||

| Sibelius 5 dynamics[26] | 20 | 39 | 61 | 71 | 84 | 98 | 113 | 127 | |||

| MuseScore 3.0 dynamics[27][failed verification] | 5 | 10 | 16 | 33 | 49 | 64 | 80 | 96 | 112 | 126 | 127 |

| MakeMusic Finale dynamics[28] | 10 | 23 | 36 | 49 | 62 | 75 | 88 | 101 | 114 | 127 | |

| SmartScore X2 dynamics[29] | 29 | 38 | 46 | 55 | 63 | 72 | 80 | 89 | 97 | 106 | |

| SmartScore 64 dynamics[30] | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 | 110 | 120 |

The velocity effect on volume depends on the particular instrument. For instance, a grand piano has a much greater volume range than a recorder.

Relation to audio dynamics

[edit]The introduction of modern recording techniques has provided alternative ways to control the dynamics of music. Dynamic range compression is used to control the dynamic range of a recording, or a single instrument. This can affect loudness variations, both at the micro-[31] and macro scale.[32] In many contexts, the meaning of the term dynamics is therefore not immediately clear. To distinguish between the different aspects of dynamics, the term performed dynamics can be used to refer to the aspects of music dynamics that is controlled exclusively by the performer.[33]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ So stark anreißen, daß die Saiten an das Holz anschlagen.

References

[edit]- ^ Thiemel, Matthias. "Dynamics". Grove Music Online (subscriber-only access). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ Read, Gardner (1969/1979). Music Notation: A Manual of Modern Practice, p.250. 2nd edition. Crescendo Publishing, part of Taplinger Publishing. ISBN 0-8008-5453-5.

- ^ a b Randel, Don Michael (2003). The Harvard Dictionary of Music (4th ed.). Cambridge, MA, US: Harvard University Press Reference Library.

- ^ "Piano". Virginia Tech Multimedia Music Dictionary. Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ^ "Forte". Virginia Tech Multimedia Music Dictionary. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ^ "Dynamics". Virginia Tech Multimedia Music Dictionary. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ^ Kennedy, Michael and Bourne, Joyce: The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music (1996), entry "Hairpins".

- ^ Gerou, Tom; Lusk, Linda (1996). Essential Dictionary of Music Notation: The Most Practical and Concise Source for Music Notation. Van Nuys, CA: Alfred Music Publishing. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-0882847306.

- ^ An Enigmatic Marking Explained, by Jeffrey Solow, Violoncello Society Newsletter, Spring 2000

- ^ Holst, Gustav (1921). The Planets. London: Goodwin & Tabb. pp. 29, 42, 159. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Tchaikovsky, Peter Ilyitch (1979). Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Symphonies in Full Score. New York: Dover Publications. First movement, just before Allegro vivo. ISBN 048623861X. OCLC 6414366.

- ^ Nikolayev, Aleksandr (ed.). P.I. Tchaikovsky: Complete Collected Works, Vol. 25. p. 79. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Tchaikovsky, Peter Ilyich (1979). Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Symphonies in Full Score. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 18, 65 [on PDF]. ISBN 048623861X. OCLC 6414366.

- ^ See imslp- p.88, Andante non tanto.

- ^ (1965). The Musical Times, Vol. 106. Novello.

- ^ Rachmaninoff, Sergei (1911). Thümer, Otto Gustav (ed.). Album Book I. Op. 3, Nos. 1–5. London: Augener. p. 5. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Mahler, Gustav (1909). Symphonie No. 7. Leipzig: Eulenburg. p. 229. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Nielsen, Carl. Fjeldsøe, Michael (ed.). Vaerker, Series II, No.5. p. 128. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Ferneyhough, Brian (1982). Lemma-Icon-Epigram. London: Edition Peters 7233.

- ^ "Extremes of Conventional Music Notation".

- ^ Kirzinger, Robert. "György Ligeti – Cello Concerto". allmusic. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ "György Ligeti – Études for Piano (Book 2), No. 9 [3/9]". YouTube. 6 April 2015. Event occurs at 3:34. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ "György Ligeti – Études for Piano (Book 2), No. 13 [7/9]". YouTube. 2 September 2015. Event occurs at 5:12–5:14. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ Donington, Robert: Baroque Music (1982) WW Norton, 1982. ISBN 0-393-30052-8. Page 33.

- ^ "Logic Pro X: Use step input recording techniques". Archived from the original on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ^ Spreadbury, Daniel; Eastwood, Michael; Finn, Ben; and Finn, Jonathan (March 2008). Sibelius 5 Reference. Edition 5.2. Sibelius Software.

- ^ "Handbook 3.0, Dynamics".

- ^ MakeMusic, Inc. Finale (Version 26), Expression Dialog Box, Note Expression Selection. Finale (26.1.0.397) Software.

- ^ Musitek Corp. Smartscore X2 Software.

- ^ Musitek Corp. Smartscore 64 Software.

- ^ Katz, Robert (2002). Mastering Audio. Amsterdam: Boston. p. 109. ISBN 0-240-80545-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Deruty, Emmanuel (September 2011). "'Dynamic Range' & The Loudness War". Sound on Sound. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ Elowsson, Anders; Friberg, Anders (2017). "Predicting the perception of performed dynamics in music audio with ensemble learning" (PDF). The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 141 (3): 2224–2242. Bibcode:2017ASAJ..141.2224E. doi:10.1121/1.4978245. PMID 28372147. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 January 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

Dynamics (music)

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Purpose

In music, dynamics refer to the relative loudness or softness of sound, which is distinct from absolute volume levels as it depends on context, such as the instrument or ensemble involved. This relativity allows performers to interpret volume variations in proportion to one another within a piece, rather than adhering to fixed decibel measurements. Standard terms like piano (soft) and forte (loud) denote these levels.[6] The primary purposes of dynamics are to enhance emotional expression, provide structural contrast, and guide the narrative flow of a musical composition. By varying intensity, dynamics enable composers and performers to convey a spectrum of feelings, from intimacy to power, fostering a deeper connection with listeners.[7] They create contrast between sections, highlighting thematic developments and maintaining listener engagement through shifts in energy.[8] Additionally, dynamics shape the overall arc of a piece, building toward climaxes or resolving intensity to mirror storytelling elements.[9] For instance, in a symphony movement, dynamics often build tension through gradual increases in volume leading to a forceful release, amplifying dramatic impact and emotional depth.[10] This technique underscores structural elements like development and recapitulation, where rising dynamics heighten anticipation before a sudden softening provides relief.[6] Dynamics can be static, sustaining a uniform level of loudness or softness to maintain mood stability, or variable, involving changes that add expressiveness and movement. Static dynamics emphasize consistency, as in sustained soft passages for contemplative effect, while variable dynamics—whether gradual or abrupt—drive progression and variety.[9]Interpretation in Performance

Musicians interpret dynamic indications by considering multiple contextual factors to achieve expressive effects tailored to the performance setting. Venue acoustics play a crucial role, as concert halls with strong lateral reflections can enhance perceived dynamic range by amplifying early reflections while attenuating later ones, allowing for greater contrast between soft and loud passages.[11] Ensemble size influences dynamics, with larger groups requiring adjusted volume levels to maintain balance and clarity, particularly in orchestral settings where collective sound projection must align with the hall's reverberation time.[12] Instrument capabilities also shape interpretation; for instance, wind instruments' dynamic range is limited by respiratory capacity, while string and keyboard instruments offer wider variability through mechanical adjustments.[13] Conductor decisions further guide these choices, serving as the primary arbiter for phrasing, tempo, and dynamic balances across the ensemble to unify the artistic vision.[14] Realizing dynamics involves instrument-specific techniques that performers refine through practice to convey emotional nuance. For wind players, breath control is essential, modulating air pressure and flow to transition smoothly between pianissimo and fortissimo, as supported by studies on respiratory patterns in instrumentalists. String performers achieve dynamic variation primarily through bow pressure and speed, where increased pressure produces louder tones and varied velocity shapes timbre and intensity without altering pitch.[15] On the piano, pedal use enhances dynamics by sustaining resonance for crescendos or blending notes in softer passages, allowing subtle gradations that extend the instrument's natural decay.[16] Performer discretion is vital when dynamic notations are ambiguous, enabling artistic adaptation while respecting the composer's intent. In cases of unclear markings, such as vague crescendo indications, musicians may integrate rubato—subtle tempo fluctuations—to heighten dynamic shifts, creating a more fluid emotional arc that aligns with the phrase's structure.[17] This interpretive freedom fosters collaboration in ensembles, where individual adjustments contribute to overall cohesion, as observed in string quartets developing shared dynamics through repeated rehearsals.[18] A notable case study is Leonard Bernstein's interpretations of Beethoven's symphonies with the New York Philharmonic. His approach, characterized by emotional intensity and precise cues, amplified Beethoven's structural elements, influencing subsequent orchestral performances by prioritizing expressive breadth over strict literalism.[19]Notation and Markings

Standard Dynamic Symbols

Standard dynamic symbols in music notation consist of a graduated scale of Italian terms and their abbreviations, which denote relative volume levels from very soft to very loud. These include pianissimo (pp) for very soft, piano (p) for soft, mezzo-piano (mp) for moderately soft, mezzo-forte (mf) for moderately loud, forte (f) for loud, and fortissimo (ff) for very loud. The terms establish a hierarchy of intensity, allowing composers to specify the overall loudness at specific points in the score, thereby shaping the emotional contour of the piece.[20] The Italian origins of these symbols trace back to the Baroque era, when Italy served as the epicenter of European music composition, leading to the adoption of its language for expressive notations. Although early dynamic indications appeared sporadically in the late 16th and 17th centuries, the symbols were standardized in the 18th century, coinciding with the development of the fortepiano, which enabled precise control over volume variations in performance.[21][22] In musical scores, these symbols are conventionally placed below the staff for instrumental parts, centered under the affected notes or at the beginning of the phrase to indicate sustained levels. For vocal music, they are positioned above the staff to avoid interference with lyrics. In Mozart's piano sonatas, such as K. 280, dynamic markings like p and f appear below the staff, often contrasting to highlight thematic development and create dramatic tension.[23][24][25] Usage of these symbols varies across instrument families due to differences in timbral and mechanical capabilities. In orchestral settings, symbols direct the ensemble's collective balance, where a forte might involve full section participation to achieve projection. For organ music, the same symbols guide adjustments in registration—changing stops to alter pipe combinations—resulting in more discrete volume shifts compared to the continuous blending in orchestral contexts.[26]| Symbol | Term | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| pp | pianissimo | very soft |

| p | piano | soft |

| mp | mezzo-piano | moderately soft |

| mf | mezzo-forte | moderately loud |

| f | forte | loud |

| ff | fortissimo | very loud |