Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

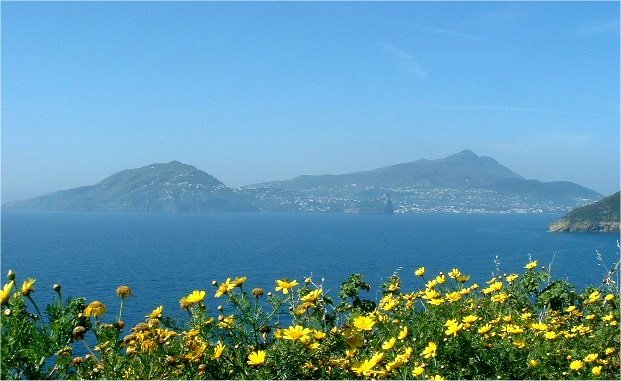

Ischia

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2018) |

Key Information

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Tyrrhenian Sea |

| Area | 47 km2 (18 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 789 m (2589 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount Epomeo |

| Administration | |

Italy | |

| Region | Campania |

| Metropolitan City | Naples |

| Largest settlement | Ischia (pop. 18,253) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 20,000 |

| Pop. density | 1,339.7/km2 (3469.8/sq mi) |

Ischia (/ˈɪskiə/ ISK-ee-ə, Italian: [ˈiskja], Neapolitan: [ˈiʃkjə]) is a volcanic island in the Tyrrhenian Sea. It lies at the northern end of the Gulf of Naples, about 30 kilometres (19 miles) from the city of Naples. It is the largest of the Phlegrean Islands. Although inhabited since the Bronze Age, as a Greek emporium it was founded in the 8th or 9th century BCE, and known as Πιθηκοῦσαι, Pithekoūsai.[2]

Roughly trapezoidal in shape, it measures approximately 10 km (6 miles) east to west and 7 km (4 miles) north to south and has about 34 km (21 miles) of coastline and a surface area of 47 square kilometres (18.1 sq mi). It is almost entirely mountainous; the highest peak is Mount Epomeo, at 788 metres (2,585 feet).[3] The island is not very densely populated, with 20,000 residents. Ischia is the name of the main comune of the island. The other comuni of the island are Barano d'Ischia, Casamicciola Terme, Forio, Lacco Ameno and Serrara Fontana.

Geology and geography

[edit]The roughly trapezoidal island is formed by a complex volcano immediately southwest of the Campi Flegrei area at the western side of the Bay of Naples. The eruption of the trachytic Green Tuff Ignimbrite about 56,000 years ago was followed by the formation of a caldera comprising almost the entire island and some of the surrounding seabed.[4] The highest point of the island, Monte Epomeo (788 m (2,585 ft)), is a volcanic horst consisting of green tuff that was submerged after its eruption and then uplifted. Volcanism on the island has been significantly affected by tectonism that formed a series of horsts and grabens; resurgent doming produced at least 800 m (2,600 ft) of uplift during the past 33,000 years.[5] Many small monogenetic volcanoes formed around the uplifted block. Volcanism during the Holocene produced a series of pumiceous tephras, tuff rings, lava domes, and lava flows.[6] The last eruption of Ischia, in 1302, produced a spatter cone and the Arso lava flow, which reached the NE coast.

The surrounding waters including gulfs of Gaeta,[7][8] Naples and Pozzuoli are both rich and healthy, providing a habitat for around 7 species of whales and dolphins including gigantic fin and sperm whales. Special research programmes on local cetaceans have been conducted to monitor and protect this bio-diversity.[9][10]

From its roughly trapezoidal shape, the island is approximately 18 nautical miles from Naples, 10 km wide from east to west, 7 km from north to south, with a coastline of 43 km and an area of approximately 46.3 km2. The highest elevation is Monte Epomeo, standing at 788 meters and located in the center of the island. This is an horst, a tectonic volcano, meaning a block of the Earth's crust that has been uplifted compared to the surrounding crust due to magmatic pressure (horst is a German term meaning "rock"). Monte Epomeo is mistakenly thought of as a volcano, although it lacks any volcanic characteristics. Island volcanism, in fact, is particularly prevalent along the fractures that border the horst, namely Monte Epomeo.

Strabo reports what the Greek historian Timeo said about a tsunami that occurred in Ischia shortly before his time. Following the volcanic activity of Epomeo, "...the sea receded for three stages; afterwards (...) it turned back again and its ebb tide submerged the island (...) those who lived on the mainland fled from the coast into the interior of Campania" (Geography V, 4, 9). Cumae, not far from that coast, in Greek means "wave". Volcanic activity on Ischia has generally been characterized by eruptions that were not very significant and occurred at great intervals. After eruptions in Greek and Roman times, the last one occurred in 1302 in the eastern sector of the island with a brief flow (known as Arso) reaching the sea.[11]

Name

[edit]

The Greeks called their colony on the island Pithekoussai (Πιθηκοῦσσαι), from which the Latin name Pithecusa was derived. The name has an uncertain etymology. According to Ovid (Metamorphoses 14.92) and the Alexandrian historian Senagora, the name would derive from pithekos, monkey, and refer to the myth of the Cercopes, inhabitants of the Phlegraean islands transformed by Zeus into monkeys. More plausible is the interpretation of Pliny the Elder (Nat. Hist. 111, 6.82), who instead derives the name from pythos, amphora, a theory supported by archaeological finds that testify to the Greek-Italic production of ceramics (and in particular of wine amphorae) on the island and in the Gulf of Naples. [12]

It has also been proposed that the name describes a characteristic of the island, rich in pine forests. "Pitueois" (rich in pines), "pituis" (pine cone), "pissa, pitta" (resin) appear as descriptive terms from which Pithekoussai could derive, meaning "island of resin," an important substance used, among other things, to waterproof wine vessels. The name Aenaria, also used by the Latins, is linked to metallurgical workshops (from aenus, metal) located on the eastern coast, under the castle.

The first evidence of the island's current toponym dates back to the year 812, in a letter from Pope Leo III in which he informs Emperor Charlemagne of devastations that occurred in the area, calling the island Iscla maior: "Ingressi sunt ipsi nefandissimi Mauri [...] in insulam, quae dicitur Iscla maiore, non longe a Neapolitana urbe." Some scholars connect the term to the Phoenician word, and therefore Semitic i-schra, "black island." The Phoenician presence on the island is archaeologically documented from a very ancient era and, as reported by Moscati (an Italian historian), in the spread in Campania and southern Etruria, since the 8th century BC, of objects of Egyptian production or inspiration, "the Phoenician merchants settled in Ischia and then frequented the Tyrrhenian coasts" certainly played a part.

On the other hand, the modern "Island of Ischia" could derive from the Latin "insula visca" – compare the Greek noun (ϝ)ἰξός, (w)ixós, (mistletoe) and the adjective (ϝ)ἰξώδης, (w)ixṓdēs, (viscous, sticky), which as usual have lost the initial digamma. In favor of this theory could be the fact that in the same area, at the foot of Vesuvius covered with pines, the popular name of Herculaneum was "Resìna," perhaps reminiscent of an ancient market for this product, similarly to the toponym "Pizzo" in Calabria, from where the best resin, the "pece brettia" obtained from the pines of the nearby Sila, came from.

Virgil poetically referred to it as Inarime and still later as Arime.[13] Martianus Capella followed Virgil in this allusive name, which was never in common circulation: the Romans called it Aenaria, the Greeks, Πιθηκοῦσαι, Pithekoūsai.[14]

(In)arime and Pithekousai both appear to derive from words for "monkey" (Etruscan arimos,[15] Ancient Greek πίθηκος, píthēkos, "monkey"). However, Pliny derives the Greek name from the local clay deposits, not from píthēkos; he explains the Latin name Aenaria as connected to a landing by Aeneas (Princeton Encyclopedia). If the island actually was, like Gibraltar, home to a population of monkeys, they were already extinct by historical times as no record of them is mentioned in ancient sources.

History

[edit]Ancient times

[edit]An acropolis site of the Monte Vico area was inhabited from the Bronze Age, as Mycenaean and Iron Age pottery findings attest. Euboean Greeks from Eretria and Chalcis arrived in the 8th century BC to establish an emporium for trade with the Etruscans of the mainland. This settlement was home to a mixed population of Greeks, Etruscans, and Phoenicians. Because of its fine harbor and the safety from raids afforded by the sea, the settlement of Pithecusae became successful through trade in iron and with mainland Italy; in 700 BC Pithecusae was home to 5,000–10,000 people.[16]

The ceramic Euboean artifact inscribed with a reference to "Nestor's Cup" was discovered in a grave on the island in 1953. Engraved upon the cup are a few lines written in the Greek alphabet. Dating from c. 730 BC, it is one of the most important testimonies to the early Greek alphabet, from which the Latin alphabet descended via the Etruscan alphabet. According to certain scholars the inscription also might be the oldest written reference to the Iliad.

In 474 BC, Hiero I of Syracuse came to the aid of the Cumaeans, who lived on the mainland opposite Ischia, against the Etruscans and defeated them on the sea. He occupied Ischia and the surrounding Parthenopean islands and left behind a garrison to build a fortress before the city of Ischia itself. This was still extant in the Middle Ages, but the original garrison fled before the eruptions of 470 BC and the island was taken over by Neapolitans. The Romans seized Ischia (and Naples) in 322 BC.

From 1st century AD to 16th century

[edit]

In 6 AD, Augustus restored the island to Naples in exchange for Capri. Ischia suffered from the barbarian invasions, being taken first by the Heruli then by the Ostrogoths, being ultimately absorbed into the Eastern Roman Empire. The Byzantines gave the island over to Naples in 588 and by 661 it was being administered by a Count liege to the Duke of Naples. The area was devastated by the Saracens in 813 and 847; in 1004 it was occupied by Henry II of Germany; the Norman Roger II of Sicily took it in 1130 granting the island to the Norman Aldoyn de Candida created Count d’Ischia; the island was raided by the Pisans in 1135 and 1137 and subsequently fell under the Hohenstaufen and then Angevin rule. After the Sicilian Vespers in 1282, the island rebelled, recognizing Peter III of Aragon, but was retaken by the Angevins the following year. It was conquered in 1284 by the forces of Aragon and Charles II of Anjou was unable to successfully retake it until 1299.

As a consequence of the island's last eruption in 1302, the population fled to Baia where they remained for 4 years. In 1320 Robert of Anjou and his wife Sancia visited the island and were hosted by Cesare Sterlich, who had been sent by Charles II from the Holy See to govern the island in 1306 and was by this time nearly 100 years of age.

Ischia suffered greatly in the struggles between the Angevin and Durazzo dynasties. It was taken by Charles III of Naples in 1382, retaken by Louis II of Anjou in 1385 and captured yet again by Ladislaus of Naples in 1386; it was sacked by the fleet of the Antipope John XXIII under the command of Gaspare Cossa in 1410 only to be retaken by Ladislaus the following year. In 1422 Joan II gave the island to her adoptive son Alfonso V of Aragon, though, when he fell into disgrace, she retook it with the help of Genoa in 1424. In 1438 Alfonso reoccupied the castle, kicking out all the men and proclaiming it an Aragonese colony, marrying to his garrison the wives and daughters of the expelled. He set about building a bridge linking the castle to the rest of the island and he carved out a large gallery, both of which are still to be seen today. In 1442, he gave the island to one of his favorites, Lucretia d'Alagno, who in turn entrusted the island's governance to her brother-in-law, Giovanni Torella. Upon the death of Alfonso in 1458, they returned the island to the Angevin side. Ferdinand I of Naples ordered Alessandro Sforza to chase Torella out of the castle and gave the island over, in 1462, to Garceraldo Requesens. In 1464, after a brief Torellan insurrection, Marino Caracciolo was set up as governor.

In February 1495, with the arrival of Charles VIII, Ferdinand II landed on the island and took possession of the castle, and, after having killed the disloyal castellan Giusto di Candida with his own hands, left the island under the control of Innico d'Avalos, marquis of Pescara and Vasto, who ably defended the place from the French flotilla. With him came his sister Costanza and through them they founded the D'Avalos dynasty which would last on the island into the 18th century.

16th–18th centuries

[edit]

Throughout the 16th century, the island suffered the incursions of pirates and Barbary privateers from North Africa: in 1543 and 1544 Hayreddin Barbarossa laid waste to the island, taking 4,000 prisoners in the process.[17][18] In 1548 and 1552, Ischia was beset by his successor Dragut Rais. With the increasing rarity and diminishing severity of the piratical attacks later in the century and the construction of better defences, the islanders began to venture out of the castle and it was then that the historic centre of the town of Ischia was begun. Even so, many inhabitants still ended up slaves to the pirates, the last known being taken in 1796. During the 1647 revolution of Masaniello, there was an attempted rebellion against the feudal landowners.

Since the 18th century

[edit]

With the extinction of the D'Avalos line in 1729, the island reverted to state property. In March 1734 it was taken by the Bourbons and administered by a royal governor seated within the castle. The island participated in the short-lived Republic of Naples starting in March 1799 but by April 3 Commodore Thomas Troubridge under the command of Lord Nelson had put down the revolt on Ischia as well as on neighboring Procida. By decree of the governor, many of the rebels were hanged in a square on Procida now called Piazza dei martiri (Square of the Martyrs). Among these was Francesco Buonocore who had received the island to administer from the French Championnet in Naples. On February 13, 1806, the island was occupied by the French and on the 24th was unsuccessfully attacked by the British.

On June 21 and 22, 1809 the islands of Ischia and Procida were attacked by an Anglo-Bourbon fleet. Procida surrendered on June 24 and Ischia soon afterwards. However the British soon returned to their bases in Sicily and Malta.[19] In the 19th century Ischia was a popular travel destination for European nobility.

On July 28, 1883, an earthquake destroyed the villages of Casamicciola Terme and Lacco Ameno.

Ischia developed into a well-known artist colony at the beginning of the 20th century. Writers and painters from all over the world were attracted. Eduard Bargheer, Hans Purrmann and Arrigo Wittler lived on the island. Rudolf Levy, Werner Gilles, Max Peiffer Watenphul with Kurt Craemer and Vincent Weber stayed in the fishing village of Sant'Angelo on the southern tip of the island shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War. In 1936 Ischia had a population of 30,418.[20]

Spa tourism did not start again until the early 1950s. At that time, a quite remarkable artist colony of writers, composers and visual artists lived in Forio, including Ingeborg Bachmann. Elizabeth Taylor and Luchino Visconti stayed here for filming. On August 21, 2017, Ischia had an 4.2 magnitude earthquake[21] which killed 2 people and injured 42 more.[22][23]

Today, Ischia is a popular tourist destination, welcoming up to 6 million visitors per year, mainly from the Italian mainland as well as other European countries like Germany and the United Kingdom (approximately 5,000 Germans are resident on the island), although it has become an increasingly popular destination for Eastern Europeans. The number of Russian guests rose steadily from the 2000s onwards,[24] before the number came to an almost complete standstill due to the currency depreciation of the ruble and COVID-19 pandemic.

From Ischia, various destinations such as Naples, Vesuvius, Amalfi Coast, Capri, Herculaneum, Paestum and the neighboring island Procida can be booked. Ischia is easily reached by ferry from Naples. The number of thermal spas on the islands makes it particularly popular with tourists seeking "wellness" holidays. A regular visitor was Angela Merkel, the former German chancellor.

In literature and the arts

[edit]

Events

[edit]The island is home to the Ischia Film Festival, an international cinema competition celebrated in June or July, dedicated to all the works that have promoted the value of the local territory.

Notable guests and works

[edit]- The Italian politician Giuseppe Garibaldi, one of the most important figures of Italian unification, stayed on the island for healing himself from a serious injury and finding relief in the peaceful area of Casamicciola Terme (at the Manzi Hotel).

- The Russian revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin, stayed in Ischia between July 1866 and June 1867, from where he wrote political letters to Alexander Herzen and Nikolai Ogarev.

- In May 1948 W. H. Auden wrote his poem "In Praise of Limestone" here, the first poem he wrote in Italy.[25]

- In 1949, British classical composer William Walton settled in Ischia. In 1956, he sold his London house and took up full-time residence on Ischia; he built a hilltop house at Forio, called it La Mortella, and Susana Walton created a magnificent garden there.[26] Walton lived on the island for the remainder of his life and died there in 1983.[27]

- German composer Hans Werner Henze lived on the island from 1953 to 1956 and wrote his Quattro Poemi (1955) there.[citation needed]

- Samuel Taylor's Broadway play Avanti! (1968) takes place on the island.

- Hergé's series of comic albums, The Adventures of Tintin (1907–1983), ends in Ischia, which serves as the location of Endaddine Akass' villa in the unfinished 24th and final book, Tintin and Alph-Art.

- French novelist Pascal Quignard set much of his novel Villa Amalia (2006) on the island.

- In Elena Ferrante's series of Neapolitan Novels, the island serves as the setting of several summer holidays of the main characters.

Film setting

[edit]In addition to the works noted above, multiple media works have been set or filmed on the island. For example:

- The American swashbuckler film The Crimson Pirate (1952) was filmed on and around the island during the summer of 1951.[28]

- Part of Purple Noon ("Plein Soleil", 1959), directed by René Clément starring Alain Delon and Marie Laforêt

- Avanti! (1972), starring Jack Lemmon and Juliet Mills.

- Part of Cleopatra (1963), starring Elizabeth Taylor, was filmed on the island.[citation needed]

- Ischia Ponte stood in for "Mongibello" in the Hollywood film of The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999).[29]

- The American film And While We Were Here (2012), starring Kate Bosworth, was filmed on the island.[30]

- Castello Aragonese was used as the 'Riva's Fortified Fortress' island in Men in Black: International (2019).[31]

Wines

[edit]The island of Ischia is home to the eponymous Denominazione di origine controllata (DOC) that produces both red and white wines though white wines account for nearly 80% of the island's wine production. Vineyards planted within the 179 hectares (440 acres) boundaries of the DOC tend to be on volcanic soils with high pumice, phosphorus and potassium content.[32]

The white wines of the island are composed primarily of Forastera (at least 65% according to DOC regulation) and Biancolella (up to 20%) with up to 15% of other local grape varieties such as Arilla and San Lunardo. Grapes are limited to a harvest yield of no more than 10 tonnes/ha with a finished minimum alcohol level of at least 11%. For wines labeled as Bianco Superiore, the yield is further restricted to a maximum of 8 tonnes/ha with a minimum alcohol level of 12%. Only certain subareas of the Ischia DOC can produce Bianco Superiore with the blend needing to contain 50% Forastera, 40% Biancolella and 10% San Lunardo.[32]

Red wines produced under the Ischia DOC are composed of 50% Guarnaccia, 40% Piedirosso (known under the local synonym of Per'e Palummo) and 10% Barbera. Like the white wines, red grapes destined for DOC production are limited to a harvest yield of no more than 10 tonnes/ha though the minimum finished alcohol level is higher at 11.5% ABV.[32]

Main sights

[edit]

Aragonese Castle

[edit]The Aragonese Castle (Castello Aragonese, Ischia Ponte) was built on a rock near the island in 474 BC, by Hiero I of Syracuse. At the same time, two towers were built to control enemy fleets' movements. The rock was then occupied by Parthenopeans (the ancient inhabitants of Naples). In 326 BC the fortress was captured by Romans, and then again by the Parthenopeans. In 1441 Alfonso V of Aragon connected the rock to the island with a stone bridge instead of the prior wood bridge, and fortified the walls to defend the inhabitants against the raids of pirates. Around 1700, about 2000 families lived on the islet, including a Poor Clares convent, an abbey of Basilian monks (of the Greek Orthodox Church), the bishop and the seminar, and the prince, with a military garrison. There were also thirteen churches. In 1912, the castle was sold to a private owner. Today the castle is the most visited monument of the island. It is accessed through a tunnel with large openings which let the light enter. Along the tunnel there is a small chapel consecrated to Saint John Joseph of the Cross (San Giovan Giuseppe della Croce), the patron saint of the island. A more comfortable access is also possible with a modern lift. After arriving outside, it is possible to visit the Church of the Immacolata and the Cathedral of Assunta. The first was built in 1737 on the location of a smaller chapel dedicated to Saint Francis, and closed after the suppression of convents in 1806, as well as the Poor Clares convent.

Gardens of La Mortella

[edit]The gardens, located in Forio-San Francesco, were originally the property of English composer William Walton. Walton lived in the villa next to the gardens with his Argentine wife Susana. When the composer arrived on the island in 1946, he immediately called Russell Page from England to lay out the garden. Wonderful tropical and Mediterranean plants were planted and some have now reached amazing proportions. The gardens include wonderful views over the city and harbour of Forio. A museum dedicated to the life and work of William Walton now comprises part of the garden complex. There's also a recital room where renowned musical artists perform on a regular schedule.

Villa La Colombaia

[edit]Villa La Colombaia is located in Lacco Ameno and Forio territories. Surrounded by a park, the villa (called "The Dovecote") was made by Luigi Patalano, a famous local socialist and journalist. It is now the seat of a cultural institution and museum dedicated to Luchino Visconti. The institution promotes cultural activities such as music, cinema, theatre, art exhibitions, workshops and cinema reviews. The villa and the park are open to the public.

Others

[edit]- Sant'Angelo (Sant'Angelo, in the comune of Serrara Fontana)

- Maronti Beach (Barano d'Ischia)

- Church of the Soccorso' (Forio)

- Piazza S.Restituta, with the best luxury boutiques (Lacco Ameno)

- Bay of Sorgeto, with hot thermal springs (Panza)

- Poseidon Gardens – spa with several thermal pools (Panza)

- Citara Beach (Panza)

- English's Beach (Ischia)

- Pitthekoussai Archaeological museum[33]

- The Angelo Rizzoli museum[33]

Voluntary associations

[edit]Committees and associations work to promote tourism on the island, and provide services and activities for residents. Among these are:

- Il coniglio di Rocco Alfarano, associazione per la protezione del quadrupede sull’isola

- Accaparlante Società Cooperativa Sociale, Via Sant'Alessandro

- Associazione Donatori Volontari di Sangue, Via Iasolino, 1

- Associazione Nemo per la Diffusione della Cultura del Mare, via Regina Elena, 75 Cellulare: 366–1270197

- Associazione Progetto Emmaus, Via Acquedotto, 65

- A.V.I. Associazione Volontariato e Protezione Civile Isola D'Ischia, Via Delle Terme, 88

- Cooperativa Sociale Arkè onlus, Via delle Terme, 76/R Telefono: 081–981342

- Cooperativa Sociale Asat Ischia onlus, Via delle Terme, 76/R Telefono: 081–3334228

- Cooperativa Sociale kairòs onlus, Via delle Terme, 76/R

- Kalimera Società Cooperativa Sociale, Via Fondo Bosso, 20

- Pan Assoverdi Salvanatura, Via Delle Terme, 53/C

- Prima Ischia – Onlus, Via Iasolino, 102

Town twinning

[edit] Los Angeles, California, USA (2006)[34]

Los Angeles, California, USA (2006)[34] Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA (2006)[35][36]

Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA (2006)[35][36] Maloyaroslavets, Russia

Maloyaroslavets, Russia

Environmental problems

[edit]The sharp increase of the population between 1950 and 1980 and the growing inflow of tourists (in 2010 over 4 million tourists visited the island for at least one day) have increased the anthropic pressure on the island. Significant acreage of land previously used for agriculture has been developed for the construction of houses and residential structures. Most of this development has taken place without any planning and building permission.[37] As at the end of 2011, the island lacked the most basic system for sewage treatment; sewage is sent directly to the sea.[citation needed] In 2004 one of the five communities of the island commenced civil works to build a sewage treatment plant but since then the construction has not been completed and it is currently stopped.

On June 14, 2007, there was a breakage in one of the four high-voltage underwater cables forming the power line maintained by Enel S.p.A. — although never authorized by Italian authorities – between Cuma on the Campania coast and Lacco Ameno on the island of Ischia. Inside each cable there is an 18 mm‑diameter channel filled with oil under high pressure.[38] The breakage of the Enel cable resulted in the spillage of oil into the sea and into other environmental matrices – with the consequent pollution by polychlorobiphenyls (PCBs, the use of which was banned by the Italian authorities as long ago as 1984), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and linear alkyl benzenes (aromatic hydrocarbons) — in the ‘Regno di Nettuno’, a marine protected area, and the largest ecosystem in the Mediterranean Sea, designated as a ‘priority habitat’ in Annex I to the Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC) and comprising oceanic posidonia beds.[citation needed]

To reduce pollution due to cars, Ischia has been the place of the first complete sustainable mobility project applied to an urban center, created in 2017 with Enel in collaboration with Aldo Arcangioli, one the main Italian experts of green mobility, under the name of "Green Island".

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Ischia: Eruptive History". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ Quinn, Josephine Crawley (2024). How the World Made the West: A 4,000-Year History (First published ed.). London Oxford New York New Delhi Sidney: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5266-0518-4.

- ^ "Mount Epomeo". Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites.

- ^ Marmoni, G.M.; Martino, S.; Heap, M.J.; Reuschlé, T. (2017). "Gravitational slope-deformation of a resurgent caldera: New insights from the mechanical behaviour of Mt. Nuovo tuffs (Ischia Island, Italy)". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 345: 1–20. doi:10.1016/J.JVOLGEORES.2017.07.019. S2CID 134849098.

- ^ "Ischia: General Information". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- ^ "Ischia: Synonyms & Subfeatures". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ 2016. Orca avvistata (Orca sighted) www.caiccomed.com, accessed September 21, 2019

- ^ D'Alelio D.. 2016. Laggiu soffia! Cronaca di una “caccia” al capodoglio nelle acque tra Ischia e Ventotene – Leviatani, nascosti e preziosi. The Scienza Live. Retrieved on March 29, 2017

- ^ Mussi B.. Miragliuolo A.. Monzini E.. Battaglia M.. 1999. Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) feeding ground in the coastal waters of Ischia (Archipelago Campano) Archived November 23, 2020, at the Wayback Machine (pdf). The European Cetacean Society. Retrieved on March 28, 2017

- ^ RAICALDO P.. 2014. Delfini e capodogli tra Ischia e Procida. Retrieved on March 29, 2017

- ^ "Island of Ischia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ "The Island of Pithecusae: Its History and Myths". Pithecusae.it. Retrieved July 12, 2024.

- ^ His poetical allusion was apparently to the mention in Iliad (ii.783) of Typhoeus being chained down ein Arimois

- ^ The plural likely so as to include nearby Procida as well.

- ^ Robinson, Andrew (2002). Lost Languages: The Enigma of the World's Undeciphered Scripts. Nevraumont Publishing.

- ^ Jonathan M. Hall (2013). A History of the Archaic Greek World, ca. 1200–479 BCE. John Wiley & Sons. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-118-34046-2.

- ^ Syed, Muzaffar Husain; Akhtar, Syed Saud; Usmani, B. D. (2011). Concise History of Islam. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 978-9382573470.

- ^ Her Majesty's Commission, State Papers (1849). King Henry the Eighth Volume 10 Part V Foreign Correspondence 1544–45. London: H.M.S.O.

- ^ "ISCHIA – A brief history of Ischia – Austrians and Bourbons – HOTEL ISCHIA – OFFERTE HOTEL ISCHIA". www.ischiaonline.it. Archived from the original on March 10, 2018. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- ^ Columbia-Lippincott Gazetteer, p. 849

- ^ Terremoto di magnitudo Mw 3.9 del 21-08-2017 ore 20:57:51 (Italia) in zona: 1 km SW Casamicciola Terme (NA) cnt.rm.ingv.it, accessed September 21, 2019

- ^ Terremoto a Ischia, due morti e 52 feriti. Salvati i fratelli rimasti sepolti Borrelli: ‘Case con materiali scadenti’ www.corriere.it, accessed September 21, 2019

- ^ Forte terremoto a Ischia, crolli a Casamicciola. Due morti e almeno 39 feriti. Salvi tutti e tre i fratelli rimasti imprigionati sotto le macerie www.lastampa.it, accessed September 21, 2019

- ^ "Italy: Land of the rich Russian".

- ^ "Auden, Wystan Hugh (1907–1973), poet and writer". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/30775. Retrieved June 16, 2019. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Kennedy, pp. 208–209

- ^ Kennedy, pp. 75, 140, 143, 144 and 208

- ^ "Lancaster already in Italy". Screenland. Henry Publishing. October 1951. p. 74. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ The Talented Mr Ripley (1999) film locations Movie-Locations.com, Retrieved November 1, 2019

- ^ Fred Topel- Exclusive Interview: Kat Coiro on And While We Were Here September 17, 2013, www.mandatory.com, accessed September 21, 2019

- ^ Men In Black International (2019) film locations Movie-Locations.com] Retrieved November 1, 2019

- ^ a b c Saunders, P. (2004). Wine Label Language. Firefly Books. pp. 169–170. ISBN 1-55297-720-X.

- ^ a b "Museo Angelo Rizzoli – Museums – Ischia – Napoli". InCampania. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "Sister Cities of Los Angeles". Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ "A Message from the Peace Commission: Information on Cambridge's Sister Cities," February 15, 2008. Retrieved October 12, 2008.

- ^ Richard Thompson. "Looking to strengthen family ties with 'sister cities'," Boston Globe, October 12, 2008. Retrieved October 12, 2008.

- ^ Pleijel, Christian (October 22, 2015). "ENERGY AUDIT ON ISCHIA" (PDF).

- ^ "Written question – Environmental catastrophe in Ischia – E-3253/2008". www.europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

Bibliography

[edit]- Richard Stillwell, ed. Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites, 1976: Archived December 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine "Aenaria (Ischia), Italy".

- Ridgway, D. "The First Western Greeks" Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-521-42164-0

- Kennedy, Michael (1989). Portrait of Walton. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816705-1.

External links

[edit]- Visit Ischia Official Tourist Board [en]

- Ischia Photos with maps [en]

- Archaeology of Ischia Archived June 27, 2017, at the Wayback Machine (in Italian)

Ischia

View on GrokipediaGeography and Geology

Physical Features and Climate

Ischia lies in the Tyrrhenian Sea, forming part of the Gulf of Naples roughly 40 kilometers west of the Italian mainland near Naples. The island spans an area of approximately 46.3 square kilometers, presenting an oblong shape with a circumference of about 34 kilometers.[7] Its topography rises sharply from coastal zones to interior elevations, dominated by steep volcanic hills interspersed with limited coastal plains and indented bays such as Cartaromana, enclosed by rocky cliffs.[8] The highest elevation, Mount Epomeo, reaches 789 meters above sea level, offering panoramic views of the island's rugged contours and surrounding waters.[9] This varied relief, including terraced slopes and narrow littoral strips, shapes local drainage patterns and supports microhabitats from seaside dunes to elevated woodlands.[10] The climate is characteristically Mediterranean, featuring mild winters with average lows of 10–14°C from December to February and hot summers peaking at highs of 29°C in August.[11] Annual mean temperatures hover around 17.7°C, with the cool season extending from late November to early April.[12] Precipitation totals approximately 700–950 millimeters yearly, predominantly during autumn and winter months, when November often records the highest amounts exceeding 160 millimeters, fostering seasonal vegetation cycles while minimizing summer drought impacts.[13] These patterns contribute to the island's habitability, enabling year-round coastal accessibility and influencing soil moisture for terraced cultivation. Ischia's ecosystems reflect its topographic diversity, with coastal areas hosting Mediterranean maquis shrublands and interior slopes covered in lush greenery including chestnut groves, acacias, and vineyards adapted to the hilly terrain.[14] Marine habitats along the bays and offshore zones support Tyrrhenian Sea biodiversity, including coralline algae formations and associated fish populations, which enhance the appeal for ecotourism and sustain localized fisheries.[15] This natural endowment underpins agricultural viability, particularly for grapevines thriving on sun-exposed slopes, and bolsters the island's draw for visitors seeking varied landscapes from cliffside vistas to sheltered inlets.[10]Volcanic Activity and Seismic Risks

Ischia, a volcanic island in the Phlegraean Fields, originated from Pleistocene-Holocene magmatic activity spanning over 150,000 years, characterized by explosive eruptions, caldera formation, and resurgent uplift centered on Mount Epomeo.[16] The island's stratigraphy includes tuffs, lavas, and pyroclastic deposits from at least 23 confirmed eruptive episodes, with the most recent in 1302 CE involving the Arso vent, which produced a 3 km-long lava flow and ash fallout affecting northern sectors.[17] [18] Classified as an active volcano by the Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV), Ischia's quiescence since 1302 reflects dormancy rather than extinction, as subsurface magma chambers remain viable based on geochemical modeling of past eruptions.[19] Ongoing hydrothermal manifestations, including fumaroles emitting gases like CO₂ and H₂S, and thermal springs with temperatures up to 90°C, indicate persistent heat from a shallow magmatic source approximately 2-3 km deep, driving a convective fluid system through permeable volcanic rocks.[20] [16] These features, concentrated in areas like Casamicciola Terme, reflect degassing from a differentiated magmatic reservoir, with fluid chemistry showing metal enrichment consistent with pre-eruptive magma exsolution under reduced pressure.[21] [22] Seismic risks stem from volcano-tectonic interactions, including caldera resurgence and fault reactivation under regional tectonic extension, which generate low-to-moderate earthquakes and contribute to slope instability in unconsolidated pyroclastic soils.[23] [24] Such dynamics exacerbate hazards like landslides, as seismic shaking reduces shear strength in ash-rich layers, though major eruptions or high-magnitude events (e.g., >M5) remain infrequent, with historical precedents like the 1883 Casamicciola quake illustrating localized amplification.[25] Continuous monitoring by INGV's Vesuvius Observatory employs seismic networks, GPS for deformation, and gas sampling to detect precursors like swarm activity or ground uplift, enabling assessment of unrest phases without presuming imminent catastrophe.[26] [27]Etymology

Origins and Historical Names

The island of Ischia bears ancient roots in nomenclature traceable to Greek colonization around 770–760 BCE, when it was designated Pithecusae (Πιθηκοῦσαι in Greek), referring to the largest island in the archipelago and likely deriving from πίθηκος (pithekos), meaning "monkey," possibly alluding to local fauna or sailors' slang for erratic winds. Pliny the Elder, in his Naturalis Historia (Book III), alternatively etymologized it from πίθος (pithos), an amphora or jar, citing the island's resemblance to storage vessels or its early pottery trade prominence, a view supported by archaeological evidence of Euboean ceramic production at sites like Lacco Ameno.[28][29][30] Coexisting archaic designations included Inarime, evoked in Homeric and Hesiodic mythology as the site of Typhoeus's imprisonment beneath volcanic fires, reflecting the island's seismic activity and Etruscan or pre-Greek influences interpreting it as a fiery or smoky land. Under Roman administration from circa 322 BCE, it became Aenaria, a name Pliny and Strabo attributed to Aeneas's legendary fleet anchorage during his voyage from Troy, emphasizing its strategic maritime role rather than mythological invention.[31][32][33] By the early medieval period, Latin usage shifted to Iscla (or Iscla maior to distinguish it from adjacent islets), a phonetic contraction of insula ("island"), first documented in 813 CE within a letter from Pope Leo III to Charlemagne granting ecclesiastical oversight. This form persisted in charters through Norman and Angevin rule, evolving phonetically into the modern Italian Ischia by the Renaissance, with standardization in official records following Italy's 1861 unification, absent any ideological renaming.[34][35]History

Ancient and Roman Periods

Archaeological evidence indicates sparse human settlement on Ischia during the Neolithic period, with the oldest traces dating to approximately 3500–3000 BC, consisting of isolated pottery and tools primarily from coastal sites.[36][37] These findings suggest limited, intermittent occupation rather than organized communities, likely tied to the island's volcanic resources and proximity to the mainland.[38] The island, known anciently as Pithecusae (Πιθηκοῦσαι in Greek), saw its first significant colonization in the mid-8th century BC, around 770 BC, by settlers from Eretria and Chalcis on Euboea, establishing it as the earliest documented Greek colony in the western Mediterranean.[39][40] Excavations at sites like the San Montano necropolis reveal a thriving emporion, or trade hub, evidenced by imported Euboean pottery, Phoenician amphorae, and the famous Nestor's Cup inscription alluding to wine consumption and commerce, underscoring Pithecusae's role in early wine trade networks across the Tyrrhenian Sea.[41] This settlement served as a staging point for further Greek expansion, including the founding of Cumae on the nearby mainland around 750 BC, leveraging the island's strategic position at the crossroads of Mediterranean routes for metals, ceramics, and agricultural goods.[41] Greek inhabitants exploited the island's thermal springs for therapeutic purposes, as indicated by early sanctuary dedications and bathing structures, marking the origins of Ischia's enduring geothermal utilization.[42] Roman domination followed the conquest of Campania in the late 4th to 3rd centuries BC, after the Pyrrhic Wars and Samnite conflicts, with Ischia—renamed Aenaria—integrated into the expanding republic by circa 300 BC.[40] Under Roman rule, the island developed as a resort destination for elites, featuring luxurious coastal villas with mosaics, frescoes, and statuary, as uncovered in submerged ruins off the Citara coast, reflecting its appeal for leisure amid volcanic landscapes.[43] Romans continued and expanded Greek thermal practices, channeling hot springs into balneae for treatments of rheumatism and skin ailments, supported by excavation evidence of pipes and basins from the 1st century BC onward.[44] The island experienced seismic and eruptive activity, including ash falls and tremors documented in regional annals, though major disruptions were episodic rather than cataclysmic during this era.[38] Settlement continuity waned with the Western Roman Empire's collapse in the 5th century AD, as trade networks fragmented and defensive priorities shifted, leading to depopulation evidenced by abandoned villa sites and reduced artifact layers in stratigraphic digs.[31] Thermal usage persisted locally among remnant populations, per scattered excavation finds, but the island's prominence as a cultural and economic node diminished until medieval revivals.[42]Medieval to Early Modern Era

Following the decline of Roman authority, Ischia came under Byzantine control in the 6th century as part of the Exarchate of Ravenna's oversight of southern Italy. The island experienced raids by Saracens in 813 and 847, disrupting local settlements during this period of Byzantine-Lombard tensions.[45] In 1130, Norman forces under Roger II of Sicily conquered Ischia, integrating it into the Kingdom of Sicily and initiating feudal governance.[46] Under Angevin rule after Charles I of Anjou's conquest of Naples in 1266, Ischia saw continued feudal administration, with the island's castle serving as a key defensive outpost.[46] Aragonese king Alfonso V significantly expanded the castle in 1441, constructing a 220-meter stone bridge linking the islet to the mainland and fortifying it against invasions, housing up to 2,000 residents during threats.[46] These enhancements reflected adaptive defenses amid regional power shifts. The 1302 eruption of Monte Arso produced a spatter cone and lava flow extending to the northeastern coast, displacing populations and burying settlements in the Zaro valley.[17] This event, the island's last major volcanic activity, prompted resettlement and reinforced the need for fortified refuges like the Aragonese Castle.[47] Recurrent Ottoman raids in the 15th and 16th centuries, including Hayreddin Barbarossa's 1544 siege, devastated coastal areas and spurred construction of watchtowers such as the Torrione di Forio to detect pirate incursions.[48] These threats accelerated defensive adaptations, concentrating populations in elevated strongholds. Under Spanish viceroyalty from 1504, Ischia's feudal system emphasized agriculture, with stability enabling expansion of cultivable lands beyond fortified zones for crops and vineyards.[45] This shift reduced reliance on the castle for residence, fostering rural development amid persistent seismic risks.[46]19th Century to Contemporary Developments

Following the Bourbon restoration in Europe after the Napoleonic Wars, Ischia integrated into the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in 1815, remaining under Bourbon rule until the Risorgimento culminated in its annexation to the newly formed Kingdom of Italy in 1861 and formal incorporation into the province of Naples in 1862.[49][45] During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the island experienced a surge in thermal tourism during the Belle Époque era, attracting European nobility to its mineral-rich springs and coastal villas, which were rebuilt and expanded after seismic events like the 1883 earthquake.[50] In World War II, Ischia suffered Allied bombing raids on the night of September 8-9, 1943, shortly after Italy's armistice announcement, resulting in 13 civilian deaths; Allied naval forces subsequently occupied the island on September 16.[51] Post-war reconstruction from 1945 onward spurred rapid demographic expansion and urban development, with the island's population growing from approximately 20,000 in the 1950s to over 60,000 by the 1980s, driven by tourism and migration. However, this period also saw widespread illegal construction, as national policies like the 1985 building amnesty (condono edilizio) legalized prior violations upon payment of fines, resulting in over 27,000 applications on Ischia alone and incentivizing further unregulated building in vulnerable areas.[52] In recent decades, European Union structural funds and loans have financed infrastructure enhancements, including roads and public facilities, to mitigate the island's seismic and hydrogeological vulnerabilities, with the European Investment Bank approving €1 billion in 2024 specifically for post-earthquake (2017) and landslide reconstruction of public and private buildings.[53] The catastrophic landslide of November 26, 2022, in Casamicciola Terme—triggered by extreme rainfall on Mount Epomeo, displacing debris across 28 hectares, destroying over 30 structures, and killing 12 people—has intensified debates over regulatory enforcement, highlighting how repeated amnesties and lax oversight exacerbated risks from illegal developments in high-hazard zones.[54][55][56] Experts attribute the disaster's severity partly to such constructions, prompting calls for stricter land-use planning and demolition of non-compliant buildings despite political resistance to revoking prior legalizations.[57][58]Economy

Tourism and Hospitality

Tourism constitutes the cornerstone of Ischia's economy, drawing visitors primarily for its thermal springs, beaches, and natural landscapes, with ferries from Naples ports like Beverello handling over 1 million passengers annually as recorded in 2011 data.[59] The sector supports substantial job creation in hospitality, transportation, and services during peak summer months from June to September, when up to 300,000 tourists can occupy the island simultaneously, though this seasonality contributes to elevated off-peak unemployment among residents reliant on tourism earnings to sustain the year.[60][61] Post-COVID recovery accelerated from 2021 onward, bolstered by the "Ischia Is More" campaign initiated in May 2020 by local hoteliers and businesses to advocate sustainable practices, year-round visitation, and the island's environmental and cultural assets beyond mass summer crowds.[62][63] This initiative contrasts with pre-pandemic patterns of approximately 1 million annual day and overnight visitors as of 2010, emphasizing diversification to mitigate over-reliance on high-season influxes that strain infrastructure like ports and accommodations.[59][64] Unlike Capri, which prioritizes luxury clientele with premium pricing and upscale amenities, Ischia caters to a mass-market audience seeking value-driven stays, family-friendly options, and accessible thermal experiences, resulting in lower average costs for hotels and dining while accommodating broader demographics from Europe.[65][66] Ferry economics underpin accessibility, with slower, cheaper car ferries (over 1 hour crossing) complementing faster hydrofoils to enable high-volume arrivals without the exclusivity barriers seen on Capri.[67][59]Agriculture, Wines, and Local Products

Ischia's volcanic soils, composed of green tufa rich in phosphorus, potassium, and other minerals, impart a distinctive minerality and fertility to its agricultural output, enabling resilient cultivation despite steep terrain and seismic risks.[68][69] These soils, formed from ancient eruptions, support terraced farming systems adapted over millennia to the island's rugged topography, where vines and fruit trees are trained on slopes exposed to cooling sea breezes that enhance acidity and aroma profiles.[70][71] Viticulture dominates, with production centered on indigenous white grapes under the Ischia DOC, Italy's oldest denominazione granted in 1966. Forastera and Biancolella form the backbone, yielding crisp, mineral-driven wines that reflect the terroir's volcanic influence; Forastera provides structure and herbal notes, while Biancolella adds finesse and citrus tones, often vinified separately or blended for Ischia Bianco.[72][73][74] Vineyards, typically at 50-250 meters elevation and trained via Guyot systems, cover limited hectares due to fragmentation, but family-run estates have revived abandoned terraces, restoring ancient plots neglected since mid-20th-century emigration and seismic events.[75][76][77] Wine trade traces to 8th-century BC Greek colonists from Euboea, who established emporia for exporting amphorae-borne vintages to Etruscans, as confirmed by Pithekoussai necropolis finds including the Nestor Cup inscription referencing Homeric-era libations.[45][78][79] Other products include figs, with the native Green Ischia variety prized for its green-skinned, strawberry-fleshed fruit dried or fresh, alongside olives yielding extra-virgin oil, capers, tomatoes, and honey from small-scale farms.[80][81] Citrus cultivation, such as lemons, persists in sheltered microclimates but yields modestly compared to mainland Campania. Fisheries, targeting species in Posidonia meadows, remain marginal, constrained by tourism-driven coastal urbanization that fragments habitats and elevates pollution, with over 1 million annual visitors prioritizing hospitality over marine extraction.[82][83][59] Urban sprawl and tourism encroach on arable land, reducing vineyard extents and prompting sustainability initiatives like terrace reconstruction by estates such as Casa d'Ambra and Cantine Crateca, which leverage EU-aligned practices for organic conversion and erosion control without specific island-targeted subsidies documented.[76][84][85]Thermal Spas and Health Economy

Ischia's thermal spas trace their origins to ancient Greek colonization, with significant development during the Roman era, when elaborate bath complexes harnessed the island's geothermal waters for therapeutic purposes.[86] Archaeological evidence, including structures at sites like Cavascura, indicates Romans constructed facilities to exploit hot springs emerging from volcanic rock, promoting bathing for health and relaxation.[42] These practices persisted through medieval periods but saw revival in the 18th and 19th centuries, evolving into modern wellness infrastructure by the mid-20th century.[87] The island features approximately 103 thermal springs across 29 groups, supplemented by 69 fumarolic vents, with waters typically ranging from 20°C to over 80°C and enriched by minerals such as sodium, magnesium, bromine, iodine, and radon.[2] Notable examples include the hyperthermal springs at Cavascura, reaching 83°C and classified as salt-bromine-iodide-bicarbonate-alkaline with a pH of 7.58, and those at Negombo Thermal Park, which incorporate volcanic-origin waters high in salts and trace elements like lithium.[88] These resources support medical tourism, attracting visitors seeking treatments for conditions like arthritis, rheumatism, and skin disorders, attributed to the waters' mineral and low-level radon content, which proponents claim reduces inflammation via hormesis—a low-dose stimulation effect.[89] However, rigorous scientific reviews, such as a Cochrane analysis, find insufficient high-quality evidence that balneotherapy outperforms placebo or no treatment for rheumatoid arthritis, highlighting potential placebo contributions and risks like radon-induced carcinogenesis despite therapeutic assertions.[90][91] Prominent facilities include Negombo Thermal Park, established in the 1950s by developer Luigi Silvestri, offering 14 pools blending thermal, marine, and hydromassage options alongside a spa, steam grotto, and private beach for integrated wellness experiences.[87] Cavascura, preserving ancient Roman cave baths near Maronti Beach, provides natural hot waterfalls, steam grottos, mud applications, and saunas carved into tuff rock, emphasizing rustic, geothermal immersion.[86] Both sites, along with others, receive regulatory oversight from Italy's Ministry of Health, which recognizes certain springs—like those at Nitrodi—for therapeutic properties and reimburses up to 12 annual treatments for citizens via national health services, underscoring balneotherapy's status as conventional rather than alternative medicine.[92][93] The thermal sector drives Ischia's health economy by sustaining specialized hospitality, employing locals in spa operations, and fostering ancillary services like hydrotherapy clinics, though precise GDP attribution remains elusive amid broader tourism dominance.[94] Italy's 320 thermal establishments collectively generate over €1.5 billion annually and support 60,000 jobs, with Ischia's geothermal assets positioning it as a key node in this network, emphasizing sustainable extraction to balance demand and resource longevity.[95] Despite promotional claims, empirical scrutiny tempers enthusiasm, as controlled trials often reveal modest, non-specific benefits akin to warm-water immersion alone, prompting calls for more robust, long-term studies on mineral-specific outcomes.[96]Cultural Impact

Literature, Arts, and Notable Visitors

Ischia's scenic volcanic terrain and coastal vistas have long drawn literary figures and artists seeking inspiration from its natural contrasts of lush greenery and rugged geology. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe observed the island from the sea during his 1787 Italian travels, noting in his letters its proximity to Capri and Vesuvius as the sun rose, evoking the sublime interplay of light and form that characterized his reflections on southern landscapes.[97] While Goethe did not land on Ischia, his son August visited in 1845 and 1846, residing in Casamicciola and Lacco Ameno for health reasons amid the island's thermal springs.[98] In the mid-20th century, English poet W. H. Auden established a seasonal residence in Forio from 1948 to 1957, renting a house with his partner Chester Kallman and praising Ischia's "Edenic beauty" and relaxed rhythms in correspondence and prose, which influenced his postwar writings on idleness and place.[99] [100] Auden's memoirs and letters depict the island realistically, balancing romantic allure with everyday disruptions like local festivals and domestic chaos, rather than unalloyed paradise.[101] Christopher Isherwood, Auden's collaborator, made a brief visit in November 1955, though his accounts focus more on transient impressions than extended stays.[102] Contemporary fiction has amplified Ischia's literary profile through Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels, where the island serves as the setting for protagonist Elena Greco's formative 1950s vacation in My Brilliant Friend (published 2011), symbolizing escape from urban constraints and sparking a tourism surge among readers in the 2010s.[103] [104] Ferrante's portrayal draws on the island's class-divided resorts and thermal sites for social commentary, grounding romanticized escapes in interpersonal tensions verifiable through the novels' Naples-centric realism. The island's dramatic geology has inspired visual artists, with Austrian painter Thomas Ender capturing its cliffs and seas in 19th-century landscapes emphasizing light and topography. Early 20th-century German expressionist Werner Gilles found motifs in Ischia's terraced hills and bays, producing works that abstracted volcanic forms into vivid color planes reflective of the site's primal energy.[105] These depictions often romanticize the terrain's fertility over its seismic volatility, as evidenced in Gilles' memoirs of discovery, though empirical accounts note the landscapes' role in attracting painters via accessible ferries from Naples post-unification.[105]Film, Music, and Cultural Events

Ischia has appeared as a backdrop in several Hollywood and international films, often showcasing its volcanic terrain and azure waters as symbols of opulent leisure. The 1999 thriller The Talented Mr. Ripley, directed by Anthony Minghella and starring Matt Damon, Jude Law, and Gwyneth Paltrow, utilized Ischia for key scenes depicting the fictional resort town of "Mongibello," capturing the island's cliffs and ports to evoke mid-20th-century Mediterranean escapism.[106] Earlier productions include the 1963 epic Cleopatra, where Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton filmed sequences amid the island's rugged landscapes, and Billy Wilder's 1972 comedy Avanti!, which highlighted its serene coves for satirical takes on bureaucracy and romance.[107] These portrayals, while visually striking, have drawn critique for romanticizing Ischia as an idyllic haven, glossing over its seismic volatility and seasonal overcrowding as evidenced in post-filming analyses of location scouting reports.[108] The Ischia Film Festival, launched in 2003 and organized by Art Movie & Music, convenes annually from late June to early July, primarily at historic venues like the Aragonese Castle. It specializes in features and documentaries that underscore territorial heritage and cinematic locations, drawing global submissions without language barriers and awarding prizes for fiction, animation, and shorts.[109] [110] In recent editions, such as 2024, it hosted over 100 works, emphasizing narratives linked to place-based identity, though attendance figures hover around 5,000-10,000 visitors yearly, supplementing rather than dominating the island's tourism economy.[111] Complementing screen arts, Ischia sustains a niche music scene through retreats and festivals that leverage its isolation for creative immersion. The Giardini La Mortella botanical gardens host the Incontri Musicali series, featuring classical concerts on Saturdays and Sundays from April to October at 5:00 p.m., with programs in 2025 including chamber works by composers like Beethoven and contemporary ensembles.[112] The annual Piano & Jazz Festival, now in its sixth edition as of recent programming, spotlights improvisational sets in intimate venues, curated by local promoters to attract performers seeking respite from mainland circuits.[113] Similarly, the Ischia Chamber Music Festival, active since 2003, gathers amateur musicians for workshops and performances of Baroque and Romantic repertoire, fostering collaborative play in low-key settings that prioritize skill-building over commercial spectacle.[114] The Ischia Global Film & Music Festival integrates these strands, accepting entries via platforms like FilmFreeway for hybrid events that pair screenings with live sets, thereby amplifying performative ties to the island's genius loci without overstating their draw—official data indicate they generate targeted revenue through 200-300 artist passes and ancillary spending, distinct from mass beach tourism.[115] Such gatherings reinforce cultural continuity amid external depictions, countering filmic stereotypes by grounding events in verifiable local participation metrics from festival archives.[116]Landmarks and Attractions

Historic Fortifications and Castles

The Aragonese Castle, located on a volcanic islet at Ischia Ponte, originated as a Greek fortress constructed in 474 BC by the tyrant Hiero I of Syracuse to defend against pirate raids in the Gulf of Naples.[117][118] Its strategic position on a rocky promontory provided natural defenses, leveraging the islet's isolation and the surrounding waters to monitor maritime threats from the Tyrrhenian Sea.[46] In the 15th century, Alfonso V of Aragon significantly expanded the structure, constructing a 220-meter stone bridge in 1441 to connect the islet to the main island, enhancing accessibility while maintaining defensive capabilities through fortified walls and towers.[46][118] These additions included palaces, churches, and cisterns, transforming it into a self-sufficient stronghold that served as a residence for nobility and a prison for political detainees, including during periods of Bourbon rule.[46] Beyond the castle, Ischia features coastal watchtowers from the Spanish viceregal period in the 16th century, designed to signal pirate incursions and protect inland settlements. The Guevara Tower, also known as Michelangelo Tower, exemplifies this architecture, built as a defensive residence with thick tufa walls and embrasures for artillery, later adapted for residential use after threats diminished.[119][120] Similarly, the Costantina Tower in Forio, erected on a tufa outcrop, functioned as a refuge with narrow windows for surveillance, reflecting the era's emphasis on rapid response to coastal raids.[121] Archaeological evidence from the castle site reveals layered fortifications, including remnants of Byzantine-era modifications atop Greek foundations, underscoring its evolution as a bulwark against successive invaders exploiting the Gulf's trade routes.[117] Preservation efforts post-erosion and seismic events have focused on stabilizing these structures, with the castle now maintained as an open-air museum highlighting its architectural adaptations to volcanic terrain.[46]Gardens, Villas, and Natural Sites

La Mortella Gardens in Forio were founded in 1958 by Lady Susana Walton, wife of composer Sir William Walton, transforming a barren coastal plot into a renowned botanical collection.[122] The gardens encompass over 1,000 species of exotic plants, including rare subtropical varieties like agaves and bromeliads, which flourish due to Ischia's volcanic soil fertility and temperate microclimate with mild winters averaging 10–12°C.[122] Landscape architect Russell Page contributed to the design, incorporating terraced levels, a nymphaeum, and a Japanese garden, while a Greek-style theater hosts summer concerts; public access began in 1991 under the Walton Foundation's management.[123] Villa La Colombaia, situated in Forio's Zaro area, functions as the Luchino Visconti Museum within the film director's 1950s-acquired summer residence, originally built in the late 1800s atop medieval structures.[124] The villa integrates landscaped grounds with native Mediterranean flora amid the surrounding forest, featuring gardens that enhance its crenellated architecture and sea views, now preserved as a cultural site displaying Visconti's artifacts.[125] Mount Epomeo trails provide access to Ischia's highest elevation at 788 meters, traversing chestnut groves, volcanic outcrops, and endemic vegetation via paths like the one from Fontana village, which spans about 3 kilometers and requires roughly one hour of moderate hiking to reach the summit hermitage.[126] These routes highlight natural integration of flora such as myrtle and arbutus with geological features, though upkeep is complicated by soil instability inherent to the island's pyroclastic deposits, prone to erosion and landsliding as documented in 2006 events on nearby slopes.[127]Thermal and Coastal Features

Ischia's coastal thermal features stem from its volcanic origins, with geothermal waters emerging along the shoreline due to subsurface heat from magmatic fluids interacting with groundwater systems.[20] These manifestations include fumaroles and hot springs integrated into beaches and bays, providing natural recreational pools where seawater mixes with mineral-rich thermal outflows.[128] Maronti Beach, the island's longest at approximately 3 kilometers, features black volcanic sand and active fumaroles where steam and hot gases escape through fissures, heating the sand to around 100 degrees Celsius in spots and creating a natural sauna-like environment.[129] Nearby thermal springs, such as those at Cava Scura, contribute to the site's appeal for visitors seeking warm sand and vapor baths.[130] The beach's formation ties directly to Ischia's eruptive history, with tuff and lava deposits shaping its rugged coastline.[131] Sorgeto Bay, located on the south coast near Panza, hosts a series of natural rock-enclosed pools fed by underwater hot springs, where temperatures vary from ambient seawater to scalding levels exceeding 50 degrees Celsius.[132] Access involves descending about 234 steps from the cliff top or arriving by boat, with the site's pebble-strewn cove offering free, year-round immersion in the therapeutic vapors and mixed waters.[133] Water quality remains generally high, though natural debris and slippery rocks require caution during visits.[134]Demographics and Society

Population Distribution and Municipalities

The island of Ischia is administratively divided into six municipalities: Barano d'Ischia, Casamicciola Terme, Forio, Ischia, Lacco Ameno, and Serrara Fontana. These entities govern distinct areas across the 46.3 km² landmass, with population densities varying due to topography and urban development patterns. As of 2021 estimates derived from municipal data, the total resident population stood at approximately 62,000, reflecting a stable but slowly declining trend amid broader Italian island demographics.[135][136] Population distribution is uneven, concentrated in coastal and thermal zones. Ischia municipality, encompassing the main port and administrative center, had 19,542 residents in 2021, while Forio, known for its western cliffs and beaches, reported around 17,500. Smaller inland or elevated communes like Serrara Fontana and Lacco Ameno each hosted under 4,000 inhabitants, emphasizing the island's dispersed settlement pattern.[137][138] Tourism drives a pronounced seasonal influx, tripling the effective population during peak summer months through short-term residents and visitors, though precise daily counts fluctuate with ferry traffic and hotel occupancy. This surge strains infrastructure but underscores the island's reliance on transient demographics. Year-round residency exhibits aging characteristics typical of southern Italian locales, with ISTAT data showing higher proportions in older age brackets and net emigration of youth to mainland opportunities for employment and education.[136][59] The November 26, 2022, landslide in Casamicciola Terme displaced over 200 residents, exacerbating short-term population shifts as affected families relocated within the island or to Naples province; reconstruction efforts have since aimed to restore pre-event distributions, though some permanent outflows occurred.[139][140]Social Structures and Twinning

Voluntary associations play a key role in Ischia's civil protection efforts, particularly in response to the island's seismic and landslide vulnerabilities. Groups such as the Associazione Volontariato e Protezione Civile Isola d'Ischia (A.V.I.) and the Centro Italiano Protezione Civile Isola d'Ischia coordinate volunteer responses to emergencies, including the 2022 Casamicciola Terme landslide, providing logistical support and community mobilization.[141][142] These organizations, often radio-equipped like the G.A.R.F.I. C.B. Isola d'Ischia, focus on practical aid rather than frequent preventive drills, with seismic exercises remaining infrequent despite the 2017 earthquake that damaged structures across the island.[143][144] Ischia maintains formal twinning agreements to promote international cooperation, primarily with San Pedro, a district of Los Angeles, established on June 24, 2006, to leverage historical Italian-American ties for cultural and economic exchanges.[145] This partnership has facilitated tourism promotion and solidarity during disasters, such as the Port of Los Angeles' public support following the 2022 Ischia landslide, though documented joint projects remain limited to occasional events rather than sustained hazard-management initiatives.[146] No active twinnings with Greek islands were identified in municipal records or agreements, contrasting with informal Mediterranean tourism networks.[147]Environmental Challenges

Geological Hazards and Landslides

Ischia, a volcanic island in the Gulf of Naples, exhibits geological instability primarily due to its composition of loose pyroclastic deposits, tephra layers, and steep slopes associated with the resurgent Mount Epomeo, which reaches 788 meters elevation. These features, remnants of polygenetic volcanism active until the 1302 AD Arso eruption, predispose the terrain to mass-wasting events when saturated by intense rainfall or triggered by shallow seismicity. Hydrothermal alteration further weakens the subsurface, facilitating slope failure under hydrological loading.[16][148] Landslides on Ischia typically manifest as debris flows or rock avalanches, often initiated by rainfall exceeding 100-150 mm in short durations, which exceeds infiltration capacity in permeable tephra sequences overlying less permeable substrates. Historical records document recurrent events, with at least several major debris flows linked to seismic activity between 1228 and 1883 AD, reflecting cyclical instability tied to volcano-tectonic resurgence. INGV analyses indicate that weak tephra layers, such as those from prehistoric eruptions, act as failure planes, promoting rapid mobilization of saturated regolith downslope.[149][150][148] A prominent example occurred on November 26, 2022, in Casamicciola Terme, where over 120 mm of rain fell in six hours, triggering a debris flow from the northern flanks of Mount Epomeo. The event mobilized approximately 10,000-15,000 cubic meters of material, including volcanic ash and blocks up to several meters in diameter, channeling through Celario valley at velocities exceeding 10 m/s. This rainfall-saturated failure exploited pre-existing fractures in tuffaceous layers, resulting in 12 fatalities and widespread inundation up to 400 meters from initiation points.[55][151][140] Seismic activity exacerbates landslide risk, with shallow swarms recurring due to caldera resurgence and fluid migration. The August 21, 2017, Mw 3.9 earthquake, nucleating at 1.2 km depth near Casamicciola, induced over 1,000 minor landslides across a 2 km zone between Lacco Ameno and Casamicciola, primarily shallow slides in unconsolidated volcanics. INGV monitoring from 2017 onward has recorded ongoing microseismicity, with models highlighting shear instability in tephra-bound layers under episodic stress. Such events underscore rainfall-seismic thresholds, where cumulative pore pressure buildup lowers frictional resistance, as evidenced in post-2017 InSAR deformation analyses.[152][153][154]Human-Induced Issues: Illegal Building and Overdevelopment

Illegal construction, known in Italy as abusivismo edilizio, has proliferated on Ischia, with environmental group Legambiente reporting approximately 28,000 requests for amnesty related to unauthorized buildings submitted by island residents.[155] These structures, often villas and secondary homes built without permits, represent a substantial share of the island's housing stock, estimated at around 42% based on amnesty data and local building inventories.[156] Successive national amnesties, starting with the 1985 condono law and extending through multiple rounds until 2018—including a post-earthquake amnesty for Ischia in that year—have enabled regularization of these violations, effectively incentivizing further non-compliance by reducing penalties and enforcement risks.[157] [158] Tourism pressures have driven much of this overdevelopment, with densification occurring on steep, hydrogeologically unstable slopes to accommodate vacation properties and expand hospitality infrastructure. Local authorities have historically exhibited lax enforcement, allowing constructions in high-risk zones despite Italy's national laws prohibiting building in areas prone to landslides and floods, as documented in regional zoning plans.[155] Experts attribute this pattern to economic incentives from seasonal visitors, who numbered over 8 million annually pre-pandemic, prioritizing short-term gains over long-term stability.[159] Such unauthorized developments have empirically worsened landslide vulnerabilities by altering natural drainage, compacting soil, and removing vegetation cover, thereby accelerating debris flow velocities during heavy rainfall—as observed in the November 26, 2022, Casamicciola Terme landslide that killed 12 people and destroyed over 250 structures.[56] Legambiente and geotechnical analyses link these illegal villas directly to amplified slide impacts, noting that built-up areas in the debris path impeded water infiltration and channeled runoff into destructive torrents, a causal mechanism confirmed by post-event surveys.[155] Despite demolitions ordered for thousands of abusive structures since the 1990s, compliance remains low, perpetuating a cycle of risk accumulation on the island's fragile terrain.[160]Debates on Causation and Policy Failures

Some environmental organizations, such as Legambiente, have attributed intensified rainfall events triggering landslides on Ischia to anthropogenic climate change, arguing that extreme precipitation patterns have become more frequent and severe.[56] However, geological records indicate that the island's volcanic terrain, characterized by steep slopes, loose pyroclastic deposits, and seismic activity, has experienced major landslides for millennia, including prehistoric debris avalanches exceeding 1 km³ in volume and a documented rock slide in 1228, long before industrial emissions could have influenced global climate.[150] [161] While short-term rainfall data from the past 14 years show the 2022 event surpassing recorded maxima for multiple durations, such intense Mediterranean downpours align with historical variability in the region, underscoring the primacy of local geohazards over novel climatic shifts in causation.[162] Policy debates highlight systemic regulatory lapses, including widespread illegal construction (abusivismo) on hazard-prone slopes, where over 27,000 amnesty requests for unpermitted works—ranging from expansions to entire buildings—remain pending, often lacking drainage or stabilization measures that could mitigate runoff and slope failure.[157] Successive Italian governments have enacted multiple condoni, or building amnesties, retroactively legalizing violations for fees, a practice critics argue fosters a culture of entitlement and moral hazard by signaling impunity for risky development in seismic and hydrogeological red zones.[163] Right-leaning politicians, such as League leader Matteo Salvini, have decried these measures as counterproductive incentives that prioritize short-term economic gains over safety, while Campania Governor Vincenzo De Luca, from the center-left, warned in 2018 that Ischia-specific amnesties would inevitably lead to fatalities by enabling builds in vulnerable areas.[164] [165] Corruption allegations in permit approvals and chronic delays in enforcing demolitions of flagged illegal structures further exacerbate risks, as unremedied developments disrupt natural hydrology and load unstable soils.[166] Geologists emphasize that while precipitation acts as a trigger, human alterations—such as cementing permeable ground and channeling water onto slopes—amplify failure probabilities in a context of inherent island volatility, rather than isolated climatic extremes.[163] This interplay demands scrutiny of both natural predispositions and institutional shortcomings, with amnesties representing a politically expedient but causally reckless response to development pressures.[157]Recent Disasters and Reconstruction

On November 26, 2022, intense rainfall exceeding 250 mm in a few hours triggered a massive debris flow and landslide in the Casamicciola Terme area of Ischia, killing 12 people—including a newborn, children, and adults—and leaving one person missing initially, while destroying dozens of homes and infrastructure along unstable slopes.[167][139] The event, exacerbated by saturated soils from prior rains, swept away roads and buildings in a high-risk zone known for hydrogeological instability, prompting a national state of emergency declaration by the Italian government.[168][140] In response, reconstruction efforts gained momentum with the European Investment Bank's approval of a €1 billion framework loan in November 2024, aimed at rehabilitating public and private buildings, urban infrastructure, and enhancing climate resilience following both the 2022 landslide and prior seismic events.[53][169] By late 2024, initial relocations of affected residents had commenced, with the first 10 households moved to safer areas and approximately 100 voluntary relocations in progress, alongside plans for seismic retrofitting of vulnerable structures to mitigate future earthquake and landslide risks.[54] The FIRE project, running from 2023 to 2025, has supported these efforts by developing probabilistic models for shallow landslides in post-wildfire terrains, informed by actual blazes on Ischia in August 2023 and June 2024, to bolster overall hydrogeological resilience through multidisciplinary hydraulic and geotechnical assessments.[170] Into 2025, reconstruction plans were activated amid ongoing weather vulnerabilities, including an April evacuation of about 1,000 residents from at-risk zones due to forecasts of heavy rain and potential repeat landslides, underscoring persistent threats despite secured funding.[171] Progress has included infrastructure repairs and resilience measures, yet critiques highlight bureaucratic delays in Italy's permitting and enforcement processes as hindering faster recovery, even as EU-backed financing represents a key achievement in addressing long-term vulnerabilities without reliance on unsubstantiated climate attribution over local geological and development factors.[54][56]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Works_of_J._W._von_Goethe/Volume_12/Letters_from_Italy/Part_VIII