Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

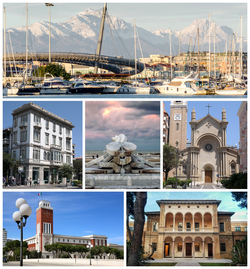

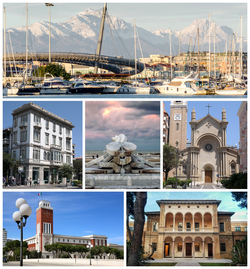

Pescara

View on Wikipedia

Pescara (Italian: [pesˈkaːra] ⓘ;[3] Abruzzese: Pescàrë; Pescarese: Piscàrë) is the capital city of the province of Pescara, in the Abruzzo region of Italy. It is the most populated city in Abruzzo, with 118,657 (January 1, 2023)[4] residents (and approximately 350,000 including the surrounding metropolitan area).[5] Located on the Adriatic coast at the mouth of the River Aterno-Pescara, the present-day municipality was formed in 1927 joining the municipalities of the old Pescara fortress, the part of the city to the south of the river, and Castellamare Adriatico, the part of the city to the north of the river. The surrounding area was formed into the province of Pescara.

Key Information

The main commercial street of the city is Corso Umberto I, which runs between two squares, starting from Piazza della Repubblica and reaching the seacoast in Piazza Primo Maggio. The rectangle that it forms with Corso Vittorio Emanuele II and Via Nicola Fabrizi is home of the main shopping district, enclosed in a driving restriction zone, where several of the best fashion shops are located. Corso Manthoné, the course of the old Pescara, has, for many years, been the center of the nightlife of the city. City hall and the administration of the province are in Piazza Italia, near the river, and in the area between here and the D'Annunzio University campus to the south, a business district has grown up over the years, while the Marina is situated to the immediate south of the mouth of the river. Pescara is also served by an international airport, the Abruzzo Airport, and one of the major touristic ports of Adriatic Sea and Italy, the Port of Pescara.

Geography

[edit]Pescara is situated at sea level on the Adriatic coast and has developed from some centuries BC onwards at the strategic position around the mouth of the Aterno-Pescara River. The coast is low and sandy and the beach extends, unbroken for some distance to both the north and the south of the river, reaching a width of approximately 140 metres (150 yd) in the area around a pineta (a small pine forest) to the north. To the south the pine forest that once gave shade to bathers along much of the Adriatic coast, has almost disappeared near the beach, but remains within the Nature Reserve Pineta Dannunziana.

The urban fabric of the city spreads over a flat T-shaped area, which occupies the valley around the river and the coastal strip. To the northwest and the southwest, the city is also expanding into the surrounding hills which were first occupied in the Neolithic period.

The whole city is affected by the presence of groundwater, the level of which varies by up to a metre, being at its highest in spring due to snow melting in the mountains inland.

The city is very close to the mountains, and the ski slopes of Passo Lanciano are a 30 minute drive away.

The city is set to expand on 1 January 2027, when neighboring towns of Montesilvano and Spoltore will be annexed into the city. The residents of the three towns voted in a referendum on the merger on 25 May 2014. 70.32% of Pescara voters approved the annexation, also 52.23% of Montesilvano and 51.15% of Spoltore voters.[6] The regional law approving the merger was passed by the regional council on 8 August 2018, with the merger to become law on 1 January 2022.[7] It was later delayed into 2023[8] and again into 2027.[9]

Climate

[edit]Pescara has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) with Mediterranean influences. The city's climate is characterized by hot summers and cool winters. Since its driest month has 34 mm (1.3 inches) of precipitation, the city cannot be solely classified as Mediterranean. Not to mention, although there is a dry tendency in early summer, August (late summer) is as wet as the winter month of February, which is unusual for the Mediterranean pattern.[10][11]

The average temperature is around 7 °C (45 °F) in the coldest month (January) and 24.5 °C (76.1 °F) in the warmest month (July). The lowest temperature recorded in the city was −13 °C (9 °F) on 4 January 1979. The highest was registered on 30 August 2007 at 45 °C (113 °F). Precipitation is low (around 676 mm (26.6 in) per annum) and concentrated mainly in the late autumn.

Pescara is a coastal city, but its climate is influenced by the surrounding mountains (the Maiella and the chain of Gran Sasso). When the wind is southwesterly, Pescara experiences a Foehn wind that often reaches 100 km/h (62 mph), causing a sudden increase in temperature and decrease in relative humidity, and for that reason winters with temperatures that exceed 20 °C (68 °F) almost daily are not unknown. Pescara experiences 35 days annually with minimum temperature below 0 °C (32 °F).[12]

Under northeasterly winds Pescara suffers precipitation which is generally weak, but can be much more intense if accompanied by a depression. Also from the north east comes winter weather from Siberia that, on average, brings abundant snowfalls every 3–4 years. In summer the weather is mostly stable and sunny with temperatures that, thanks to the sea breeze, rarely exceed 35 degrees unless a southwesterly Libeccio is blowing. Particularly in summer, but also in winter, the high humidity leads to morning and evening mist or haze.

| Climate data for Pescara (1951–2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 23.3 (73.9) |

24.4 (75.9) |

26.6 (79.9) |

30.6 (87.1) |

34.9 (94.8) |

35.4 (95.7) |

38.4 (101.1) |

40.5 (104.9) |

35.5 (95.9) |

31.2 (88.2) |

27.6 (81.7) |

26.0 (78.8) |

40.5 (104.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 10.4 (50.7) |

11.4 (52.5) |

13.5 (56.3) |

16.9 (62.4) |

21.3 (70.3) |

25.3 (77.5) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.3 (82.9) |

25.0 (77.0) |

20.4 (68.7) |

15.5 (59.9) |

11.9 (53.4) |

19.0 (66.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

7.7 (45.9) |

9.7 (49.5) |

12.7 (54.9) |

16.9 (62.4) |

20.8 (69.4) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.4 (74.1) |

20.4 (68.7) |

16.2 (61.2) |

11.8 (53.2) |

8.4 (47.1) |

14.9 (58.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.6 (38.5) |

3.9 (39.0) |

5.8 (42.4) |

8.5 (47.3) |

12.5 (54.5) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.6 (65.5) |

18.5 (65.3) |

15.8 (60.4) |

12.1 (53.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

4.8 (40.6) |

10.7 (51.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.5 (13.1) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

1.7 (35.1) |

7.3 (45.1) |

11.0 (51.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

6.3 (43.3) |

3.0 (37.4) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

−10.5 (13.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 60.8 (2.39) |

51.4 (2.02) |

59.0 (2.32) |

53.8 (2.12) |

37.5 (1.48) |

42.5 (1.67) |

35.0 (1.38) |

43.5 (1.71) |

62.6 (2.46) |

76.8 (3.02) |

78.4 (3.09) |

83.5 (3.29) |

684.8 (26.95) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.4 | 6.3 | 6.6 | 5.9 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 5.1 | 7.0 | 7.5 | 7.7 | 69.3 |

| Source: Regione Abruzzo[13] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Pescara (Abruzzo Airport), 1981–2010 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 11.4 (52.5) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.7 (58.5) |

18.1 (64.6) |

23.1 (73.6) |

27.0 (80.6) |

29.7 (85.5) |

29.5 (85.1) |

25.9 (78.6) |

21.3 (70.3) |

16.1 (61.0) |

12.7 (54.9) |

20.1 (68.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.5 (43.7) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.6 (54.7) |

17.2 (63.0) |

21.0 (69.8) |

23.6 (74.5) |

23.7 (74.7) |

20.1 (68.2) |

16.0 (60.8) |

11.1 (52.0) |

7.9 (46.2) |

14.6 (58.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.5 (34.7) |

1.7 (35.1) |

3.8 (38.8) |

7.1 (44.8) |

11.3 (52.3) |

15.0 (59.0) |

17.4 (63.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

14.3 (57.7) |

10.8 (51.4) |

6.1 (43.0) |

3.2 (37.8) |

9.2 (48.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 49.6 (1.95) |

46.2 (1.82) |

54.6 (2.15) |

46.0 (1.81) |

30.6 (1.20) |

47.2 (1.86) |

31.1 (1.22) |

41.6 (1.64) |

63.0 (2.48) |

69.0 (2.72) |

85.0 (3.35) |

75.3 (2.96) |

639.2 (25.16) |

| Average precipitation days | 5.3 | 5.5 | 5.8 | 5.4 | 4.5 | 5 | 3.1 | 3.9 | 5.1 | 6.2 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 64.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74 | 73 | 72 | 71 | 72 | 70 | 69 | 71 | 72 | 75 | 76 | 76 | 73 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 0.7 (33.3) |

0.5 (32.9) |

2.8 (37.0) |

6.2 (43.2) |

10.6 (51.1) |

14.2 (57.6) |

15.9 (60.6) |

16.6 (61.9) |

13.4 (56.1) |

10.2 (50.4) |

5.9 (42.6) |

2.4 (36.3) |

8.3 (46.9) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 96.1 | 109.2 | 151.9 | 192.0 | 241.8 | 261.0 | 303.8 | 275.9 | 219.0 | 170.5 | 111.0 | 89.9 | 2,222.1 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 3.1 | 3.9 | 4.9 | 6.4 | 7.8 | 8.7 | 9.8 | 8.9 | 7.3 | 5.5 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 6.1 |

| Source: NOAA (humidity and sun 1961–1990)[12][14] | |||||||||||||

History

[edit]

Pescara's origins precede the Roman conquest. It was founded to be the port of Vestini and Marrucini tribes to trade with the peoples of the Orient, a supporting role that was held for centuries. The name of both the town and the river was Aternum, it was connected to Rome through the Via Claudia Valeria and the Via Tiburtina. The main building was the temple of Jovis Aternium. The town was an important port for trade with the Eastern provinces of the Empire.

In the Middle Ages it was destroyed by the Lombards (597). Saint Cetteus, the town's patron saint, was a bishop of the 6th century, elected to the see of Amiternum in Sabina (today the city of San Vittorino) in 590, during the pontificate of Gregory the Great.[15] His legend goes that he was executed by the Lombards at Amiternum by being thrown off a bridge with a stone tied around his neck; his body floated to Pescara.[15]

In 1095 Pescara was a fishing village enriched with monuments and churches. In 1140 Roger of Sicily conquered the town, giving rise to a period in which it was destroyed by armies ravaging the Kingdom of Sicily. The name of Piscaria ("abounding with fish") is mentioned for the first time in this period. Several seignors ruled over Pescara afterwards, including Rainaldo Orsini, Louis of Savoy, and Francesco del Borgo, the vicar of king Ladislaus of Naples, who had the fortress and the tower built. The subsequent rulers were the D'Ávalos. In 1424 the famous condottiero Muzio Attendolo died here. Another adventurer, Jacopo Caldora, conquered the town in 1435 and 1439. In the following years Pescara was repeatedly attacked by the Venetians, and later, as part of the Spanish Kingdom of Naples, it was turned into a massive fortress.

In 1566 it was besieged by 105 Turk galleys. It resisted fiercely and the Ottomans only managed to ravage the surrounding territory.

At the beginning of the 18th century Pescara had some 3,000 inhabitants, half of them living in Castellammare, a small frazione of the fortress. In 1707 it was attacked by Austrian troops under the command of the Count of Wallis: the town, led by Giovanni Girolamo II Acquaviva, resisted for two months before capitulating.

Pescara was always part of the Kingdom of Naples, apart from the brief age of the Republic of Naples of 1798–99. The town was therefore attacked by the pro-Bourbon Giuseppe Pronio. In 1800 Pescara fell to French troops, becoming an important military stronghold of Joseph Bonaparte's reign. Castellammare, which now had 3,000 inhabitants of its own, became a separate municipality.

In 1814, Pescara's Carboneria revolted against Joachim Murat. There, on 15 May 1815, the king undersigned one of the first constitutions of the Italian Risorgimento. In the following years Pescara became a symbol of the Bourbon's violent restoration as it housed one of the most notorious Bourbon jails. After a devastating flood in 1853, Pescara was liberated by Giuseppe Garibaldi's collaborator Clemente De Caesaris in 1860. Seven years later the fortress was dismantled.

In the sixty following years Pescara was included in the Province of Chieti and then merged with the adjacent town of Castellammare Adriatico and eventually became the largest city of its region. The new city suffered heavy civilian casualties when it was bombed by the Allies who were attempting to cut German supply lines during World War II. It has since been massively rebuilt, becoming a very modern coastal city of Italy.

Demographics

[edit]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: ISTAT | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Government

[edit]Main sights

[edit]

The city is divided in two by the river in between.

The historic city center is located on the south shore, where once stood the Piazzaforte (fortified town), a military bulwark of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. There is the Bagno Borbonico (the old prison of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, built starting in 1510 by order of Charles V, which incorporated inside the remains of the Norman and Byzantine city walls). Today it houses the Museum of the Abruzzi people:[16] the institution traces, through 13 halls dedicated to aspects of life, traditions and economy, 4,000 years of history of the Abruzzo people.

In the historic city center are the birthplace houses of Gabriele D'Annunzio[17] and Ennio Flaiano, and the San Cetteo Cathedral, built between 1933 and 1938.

On the north shore of the river there's Piazza Italia (Italy Square), overlooked by the City Hall and the Government Building (which houses the headquarters of the Province of Pescara), both built during the Fascist era according to the fascist rationalist style and designed by the architect Vincenzo Pilotti. Pilotti designed the majority of the public buildings of the city, including the seat of the local Chamber of Commerce, of the Liceo Classico "G. D'Annunzio" high school,[18] and the old seat of the court (which now houses a museum).[19]

In the far southern part of the city, between the Nature Reserve Pineta Dannunziana and the beach, there is an elegant Art Nouveau villas district designed in 1912 by Antonino Liberi (an engineer brother-in-law of D'Annunzio). There is also the Aurum, first headquarters of a social club (called the Kursaal), then liquor factory, and today public multipurpose space.[20][21]

In 2007 was built the Ponte del Mare, the largest pedestrian and cycle bridge in Italy.

On the northern waterfront, close to the Salotto Square, the main square of the city, there is the Nave (trad. the ship), a sculpture by Pietro Cascella.

Economy

[edit]

Pescara is the most populous city in the Abruzzo region, and is one of the top ten economic, commercial, and tourist centers on the Adriatic coast. Featuring a shoreline that extends for more than 20 km (12 mi), Pescara is a popular seaside resort on the Adriatic coast during summer. Situated in the sea at a short distance from the waterline there are many breakwaters made with large rocks, that were placed to preserve the shore from water-flood erosion.

In the city there are the administrative headquarters of De Cecco company and the Fater S.p.a., an equal joint venture partner with the Angelini Group and Procter & Gamble.[22]

Culture

[edit]Every July Pescara holds an international jazz festival: Pescara Jazz was the first Italian summer festival dedicated to jazz music. Since 1969, it has been one of the most important jazz festivals in Europe, as reported by the main dedicated international magazines.

Every year (between June and July) the city also holds the Flaiano Prizes, one of Italy's International Film Festivals.

Pescara was the birthplace of Gabriele D'Annunzio and Ennio Flaiano. Vittoria Colonna was the marchioness of Pescara.

University

[edit]Pescara and Chieti are the homes of the G. d'Annunzio University. Pescara is home to the Departments of Architecture, Economics, Business Administration, Quantitative Economics, Social and Legal Sciences, Modern Languages Literatures and Cultures, as Chieti, together with the Rector and Academic Senate, is home to the Departments of Medicine and Science of Aging, Experimental and Clinical Sciences, Neuroscience and Imaging, Oral Health Sciences and Biotechnology, Pharmacy, Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, Humanities Psychological Sciences, Engineering and Geology, for a total of about 31,257 students in the 2011 [1].

Since 2009, Rome ISIA has a subsidiary in Pescara, training students in the field of industrial design.

In the city center is located the headquarters of ICRANet, the International Center for Relativistic Astrophysics Network, an international organization promoting research activities in relativistic astrophysics and related areas.

Sports

[edit]The city has a football team, Delfino Pescara 1936, which in June 2012 was promoted to Serie A, the highest league in Italy. Pescara Calcio, who have played 38 seasons in the cadet championship, have spent 7 previous seasons in Serie A, especially in the 1980s–90s.

Between 1924 and 1961, Pescara hosted the Coppa Acerbo automobile race, which in 1957 formed the penultimate round of the World Championship of Drivers. With a length of almost 26 km the Pescara Circuit was the longest circuit to ever host a Formula One Grand Prix.

Pescara hosted the 2009 Mediterranean Games, having defeated Rijeka, Croatia and Patras, Greece for the privilege. In 2015, from 28 August to 6 September, the first edition of the Mediterranean Beach Games was held in the city in 2015.

Since 2011 the Italian edition of the Ironman 70.3 takes place in the city of Pescara, chosen for the characteristics of the territory, for the possibility of building a competition that starts from the sea, continue towards the mountains and ends in the city center.[23]

Transport

[edit]

As regards public transport Pescara has a wide assortment of services, the city benefits from it a very favourable position with regard to roads.

Motorways

[edit]The territory between Pescara and Chieti is crossed by two pan-European roads, autostrada A14 (Italy) Bologna – Taranto, and autostrada A25 (Italy) Torano – Pescara, connected with the local bypass road system.

Airport

[edit]

Pescara is served from an international airport called Abruzzo Airport (Aeroporto di Pescara) that connects the entire region with many Italian and European destinations like Barcelona-Girona, Brussels-Charleroi, Frankfurt-Hahn, Kraków, London-Stansted,Turin, Weeze, Milan Malpensa, Tirana, Bucarest, Palermo, Catania.

Port

[edit]Pescara is served by the Port of Pescara for fishing, yachting, cargo docking and commercial passenger services. In the past, during summer season, ferries and hydrofoils to Croatia run primarily by SNAV used to connect the city to Split and islands in central Dalmatia but the service has been temporarily suspended.

Rail

[edit]The city has four railway stations, Pescara Centrale railway station is the main and largest in Abruzzo, as well as one of the larger railway stations without train terminal in Italy, connecting with some of the major Italian cities like Rome, Milan, Turin, Bologna, Bari, Ancona, Trieste and many other cities. The other stations are Pescara Porta Nuova, Pescara Tribunale and Pescara San Marco.

Bus

[edit]Pescara is served from several bus lines (operated by TUA, Società unica abruzzese di trasporto). There is a direct bus line to Roma Tiburtina (Rome) via Pescara Centrale (about a two and a half hour ride).

Trolleybus

[edit]A new trolleybus system is set to become operational. The system's initial, 8-kilometre-long (5.0 mi) route has been constructed. It connects the city center, including the Pescara Centrale railway station, with Montesilvano.[24] New Van Hool trolleybuses for use on the route have been delivered.[25] Once these have been tested and driver training completed, service will start, possibly in 2023 or 2024. A future extension to the Abruzzo International Airport and Parcheggio Sud has been proposed.[26]

People

[edit]- Federico Caffè (1914–1987), economist

- Andrea Caldarelli (born 1990), racing driver

- Giada Colagrande (born 1975), actress and film director

- Gabriele D'Annunzio (1863–1938), poet, novelist and politician

- Ildebrando D'Arcangelo (born 1969), opera singer

- Giovanni De Benedictis (born 1968), retired race walker

- Eusebio Di Francesco (born 1969), Football Manager

- Ennio Flaiano (1910–1972), screenwriter, novelist and journalist

- Simone Iacone (born 1984), racing driver

- Francesco Panzieri (born 1985), visual effects artist

- Stefano Pessina (born 1941), business man and Executive Chairman of Alliance Boots

- Stefano Prizio (born 1988), footballer

- Sara Serraiocco (born 1990), actress

- Floria Sigismondi (born 1965), Canadian photographer and director

- Enzo Trulli (born 2005), racing driver, son of Jarno Trulli

- Jarno Trulli (born 1974), former Formula One driver

- Francesco Di Fulvio (born 1993), Italian water polo player

- Marco Verratti (born 1992), Italian footballer

- Alessandro Di Renzo (born 2000), Italian footballer

Twin towns

[edit]Pescara is twinned with:

Arcachon, France

Arcachon, France Miami Beach, U.S.

Miami Beach, U.S. Lima, Peru

Lima, Peru Split, Croatia

Split, Croatia Brescia, Italy

Brescia, Italy Casale Monferrato, Italy

Casale Monferrato, Italy

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Italian National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Popolazione Residente al 1° Gennaio 2018". Italian National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Canepari, Luciano. "Dizionario di pronuncia italiana online" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ^ "Abruzzo (Italy): Provinces, Major Cities & Communes - Population Statistics, Maps, Charts, Weather and Web Information". www.citypopulation.de. Archived from the original on 26 June 2023. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ Z. Khan, Ahmed; Quynh Le, Xuan; Corijn, Eric; Canters, Frank (January 2013). Sustainability in the Coastal Urban Environment: Thematic Profiles of Resources and their Users (pdf). Rome: Sapienza University Press. p. 90. ISBN 9788895814902. Archived from the original on 22 April 2024. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Referendum 'Nuova Pescara',64% dicono sì - Notizie - Ansa.it". Agenzia ANSA (in Italian). 27 May 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- ^ "Nuovo Comune di Pescara | Città di Pescara". www.comune.pescara.it. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- ^ Centro, Il. "Nuova Pescara nascerà a gennaio 2023". il Centro. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- ^ Centro, Il. "Nuova Pescara, approvata la legge per la fusione al 2027. Il nome? Solo Pescara". il Centro. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- ^ Kottek, Markus; Grieser, Jürgen; Beck, Christoph; Rudolf, Bruno; Rube, Franz (June 2006). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated" (PDF). Meteorologische Zeitschrift. 15 (3): 259–263. Bibcode:2006MetZe..15..259K. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ^ Peel, M. C.; Finlayson, B. L.; McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. 4 (2): 439–473. doi:10.5194/hessd-4-439-2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ^ a b "WMO Climate Normals for 1981-2010: Pescara-16230" (XLS). ncei.noaa.gov. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ "VALORI MEDI CLIMATICI DAL 1951 AL 2000 NELLA REGIONE ABRUZZO" (PDF). Regione Abruzzo. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

- ^ "Pescara Climate Normals 1961–1990". NOAA (FTP). Retrieved 1 July 2016. (To view documents see Help:FTP)

- ^ a b "San Ceteo (Peregrinus) di Amiterno". Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- ^ "Museo delle Genti d'Abruzzo: index". Archived from the original on 7 September 2007. Retrieved 2 September 2007.

- ^ "Pescara". Italia:The Official Tourism Website. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ "Storia del Liceo". www.liceoclassicope.gov.it. Archived from the original on 15 May 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ "Mediamuseum". www.mediamuseum.it. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ "Storia del rione pineta dannunziana: Il Kursaal – AURUM – La nostra Storia Pescara – Abruzzo24ore.tv". www.abruzzo24ore.tv. 4 September 2013. Archived from the original on 6 February 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ "Storia – Portfolio Categories – Aurum". aurum.comune.pescara.it. Archived from the original on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ "Vision | Fater S.p.A". www.fatergroup.com. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ "IRONMAN 70.3 Italy". Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ Trolleybus Magazine No. 368 (March–April 2023), p. 74. National Trolleybus Association (UK). ISSN 0266-7452.

- ^ Trolleybus Magazine No. 367 (January–February 2023), p. 33. National Trolleybus Association (UK). ISSN 0266-7452.

- ^ Trolleybus Magazine No. 325 (January–February 2016), p. 24. National Trolleybus Association (UK).

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Pescara Airport

- Università D'Annunzio Archived 2003-09-19 at the Wayback Machine

Pescara

View on GrokipediaPescara is a coastal city and seaport in the Abruzzo region of central Italy, situated at the mouth of the Pescara River on the Adriatic Sea, and serves as the administrative capital of the Province of Pescara. The city has a population of approximately 118,500 residents within municipal boundaries, making it the most populous urban center in Abruzzo, while the broader metropolitan area encompasses over 380,000 inhabitants.[1][2]

Known primarily for its long stretches of sandy beaches and vibrant seaside promenade, Pescara functions as a key tourist destination, supported by its international airport, Abruzzo Airport, and the equipped tourist port of Marina di Pescara, which facilitate accessibility and bolster the local economy centered on services, fishing, and hospitality.[3][4][5] The city emerged as a unified entity in the early 20th century from adjacent settlements and experienced significant post-World War II expansion, evolving from a modest fishing community into Abruzzo's primary economic and transport hub.[6] Pescara is also the birthplace of the influential Italian writer and nationalist Gabriele D'Annunzio, whose family home now serves as a museum preserving his early life artifacts.[7][8]

Geography

Location and Topography

Pescara lies at the mouth of the Pescara River where it empties into the Adriatic Sea, in the Abruzzo region of central Italy's east coast.[9] The city's central coordinates are approximately 42°28′N 14°13′E.[10] This position on the alluvial plain formed by the river has historically facilitated communication and settlement between the coastal zone and inland areas.[11] The terrain consists of a low-lying, flat coastal plain at near sea level, with average elevations around 5 to 9 meters above the Adriatic.[12] Sandy beaches characterize the shoreline, extending continuously for about 4.4 kilometers in the main urban beach area, though the broader coastal strip supports further sandy expanses.[13] Inland, the plain rises gradually toward the Apennine ranges, including the Majella massif to the southwest, which forms a natural western boundary and topographic backdrop.[14] The Pescara River bisects the urban territory, separating the southern historic core from Castellammare Adriatico on the northern bank, a division formalized by municipal unification in 1927.[9] This fluvial feature contributes to the city's linear layout along the coast and influences patterns of urban expansion, while the flat topography and river dynamics elevate vulnerability to flooding in low-lying zones.[15]Environmental Features

Pescara's Adriatic coastline encompasses sandy beaches and dune systems that harbor significant botanical diversity, including endemic plant communities now rare along Italian shores due to habitat fragmentation. These dunes, part of broader Abruzzo coastal ecosystems, support specialized vegetation adapted to shifting sands and serve as buffers against erosion while fostering invertebrate and reptile populations. Wetlands adjacent to the dunes and river mouth provide critical stopover sites for migratory birds, such as the hoopoe and bee-eater, during seasonal passages across the Adriatic flyway, with regional monitoring highlighting their role in maintaining avian biodiversity amid urban pressures.[16][17][18] The Pescara River, central to the city's hydrology, sustains modest fisheries through its estuarine nutrient inputs but faces chronic pollution from upstream industrial effluents and urban runoff, resulting in elevated levels of heavy metals like chromium, nickel, and lead, as well as phthalates and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Sediment analyses reveal contamination hotspots near the river mouth, impairing benthic organisms and fish health, with ecological status classified as poor under regional assessments due to these anthropogenic inputs. Remediation efforts, including monitoring since the 2010s, have targeted legacy pollution from sites like Bussi sul Tirino landfills, yet persistent bioaccumulation threatens aquatic food webs.[19][20][21] Protected areas proximate to Pescara bolster regional conservation, including the Torre del Cerrano Marine Protected Area spanning 7 kilometers south toward Pineto, which safeguards seagrass meadows, reef-like structures, and coastal dunes against overexploitation and preserves biodiversity hotspots in the central Adriatic. Within Pescara, fragmented green corridors like pine woodlands offer limited refugia, but post-World War II reconstruction prioritized concrete infrastructure over expansive natural buffers, constraining urban ecosystems and exacerbating fragmentation. Coastal erosion, driven by wave action and sediment starvation from river damming, erodes dunes at rates up to several millimeters annually in Abruzzo stretches, per geomorphological studies, prompting EU-funded stabilization via beach nourishment.[22][23][24]Climate

Seasonal Patterns

Pescara exhibits a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa) characterized by hot, humid summers and mild, occasionally chilly winters, with Mediterranean influences moderating extremes due to its Adriatic coastal position.[25] [26] Historical data from 1991-2020 indicate average summer temperatures (June-August) of 23-26°C, with July featuring daytime highs frequently exceeding 30°C and peaking at 35°C during heatwaves, accompanied by relative humidity levels often above 60%.[27] Winters (December-February) average 7-9°C, with January lows dipping to 4-5°C and rare snowfall events occurring less than once per decade, typically accumulating under 5 cm when they do.[27] [28] Precipitation totals approximately 700 mm annually, with the majority—over 50%—falling between October and March, driven by cyclonic activity over the Mediterranean; November records the highest monthly average at 80-90 mm, while summer months see reduced rainfall of 30-50 mm, fostering drier conditions.[29] [27] Scirocco winds, originating from North African deserts, periodically influence summer weather patterns in Pescara, delivering gusts up to 40-50 km/h that elevate temperatures by 5-10°C and increase humidity, often exacerbating discomfort during July and August.[30] [31] Spring (March-May) transitions with rising temperatures from 10-20°C and variable precipitation averaging 50-60 mm per month, while autumn (September-November) mirrors this with cooling from 20-15°C and intensifying rains leading into winter. Wind regimes feature moderate northeasterly bora influences in cooler months, contrasting summer's lighter sea breezes, with annual average speeds of 10-15 km/h.[28] [27]| Month | Avg High (°C) | Avg Low (°C) | Precip (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | 11 | 5 | 65 |

| Jul | 29 | 18 | 35 |

| Annual | 18 | 11 | 700 |

Climate Change Impacts

Pescara's regional climate has warmed by approximately 0.037°C per year in the Aterno-Pescara River watershed, resulting in a total increase of about 1.6°C from the late 20th century baseline to recent decades, based on hydro-climatic data from meteorological stations and models.[32] This trend aligns with broader Mediterranean warming patterns and has manifested in intensified heat events, such as the 2023 summer heatwave that prompted red alerts for Pescara amid temperatures surpassing 40°C in Abruzzo, exacerbating risks to public health and urban infrastructure.[33] [32] Projections from regional models indicate relative sea-level rise along the Adriatic coast, including Pescara, could reach 0.5 to 1.4 meters by 2100 due to thermal expansion and ice melt, threatening submersion of low-elevation coastal plains and urban fringes where much of the city's development is concentrated at or near sea level.[34] Increased storm surges and wave heights, compounded by subsidence in vulnerable sedimentary areas between Pescara and nearby Ortona, are expected to accelerate beach erosion and flooding, potentially inundating 10-20% of low-lying zones under intermediate scenarios without accounting for local tectonic stability.[35] These changes pose direct challenges to Pescara's tourism-dependent economy, as the city's extensive sandy beaches—key attractions—face progressive degradation from heightened hydrodynamic forces.[36] Saltwater intrusion into coastal aquifers represents an emerging threat, driven by overpumping for urban and agricultural use alongside rising sea levels, with piezometric levels in Abruzzo's phreatic systems occasionally dropping below sea level and allowing saline wedging inland. Local groundwater studies in the Pescara area document elevated chloride concentrations in wells near the river mouth, signaling early salinization that could compromise drinking water supplies and irrigation for surrounding lowlands.[37] Concurrent reductions in river runoff, projected to decline under warming scenarios in the Aterno-Pescara basin, further heighten vulnerability by diminishing freshwater dilution of intruding seawater.[38] Empirical monitoring underscores these risks, though data gaps persist due to inconsistent long-term aquifer sampling in the region.History

Ancient Origins

The area encompassing modern Pescara was inhabited by the Vestini, an Italic tribe akin to the Sabines, during the Iron Age, with settlements emerging in the eastern Abruzzo region by the late 2nd millennium BCE. Aternum developed as a primary Vestini center at the Adriatic mouth of the Aterno River, leveraging its coastal position for early trade and maritime activities evidenced by port traces from the 5th century BCE. This pre-Roman foundation underscored the site's causal role as a natural conduit for exchange between Italic interior communities and Adriatic networks. Roman integration followed the subjugation of the Vestini after the Social War (91–88 BCE), transforming Aternum into a municipium and key port known as Ostia Aterni, which supported commerce across the Adriatic Sea. Archaeological remains, including tombs and structural vestiges near the ancient site, attest to its urban expansion and burial practices under Roman administration. The extension of the Via Claudia Valeria to Aternum in AD 48, commissioned by Emperor Claudius, solidified its strategic value by linking it directly to Rome via improved inland routes, thereby boosting overland supply lines to the coast. Post-5th-century disruptions from Germanic invasions eroded Aternum's cohesion, culminating in the Lombard incursion into Italy in 568 CE, which fragmented Abruzzo under decentralized duchies and diminished centralized Roman-era infrastructure.Medieval and Renaissance Periods

Following the decline of Roman authority, the area around Aternum (modern Pescara) fell under Byzantine influence during the 6th to 8th centuries, with Lombard incursions disrupting control in the 6th century as the region was annexed to the Duchy of Spoleto, excluding the coastal strip between the Tronto and Pescara rivers.[39] By the 9th century, Saracen raids intensified along the Adriatic coast, prompting local populations in Abruzzo to fortify settlements, including the construction of castles and watchtowers to defend against pirate incursions that targeted coastal ports and inland areas.[40] The Norman conquest extended to Abruzzo in the early 11th century, with adventurers like Robert Guiscard consolidating control over Adriatic territories north of Aternum after 1060, establishing feudal structures that integrated the port into the County of Apulia.[41] This period saw Aternum fortified further as a defensive outpost, though its strategic port function waned amid feudal fragmentation under local lords. Under Angevin rule after 1266, as part of the Kingdom of Naples, Pescara experienced intermittent conflicts between Angevin loyalists and Aragonese challengers, with the town changing hands during wars, including conquests by condottiero Giacomo Caldora in 1435 and 1439.[42] The Black Death struck the region in 1348, devastating nearby settlements like Popoli and causing widespread mortality that halved or more populations in Abruzzo's urban centers.[43] Aragonese victory in 1442 brought Pescara under their domain, with King Alfonso I granting the neglected harbor to admiral Francesco de Luna in 1443, emphasizing feudal oversight over revival.[42] During the Renaissance, following Spanish Habsburg acquisition of the Kingdom of Naples in 1504, Pescara remained a minor feudal holding under viceregal administration, marked by economic stagnation and a reliance on subsistence agriculture rather than urban or maritime expansion.[41] Local lords focused on agrarian production in the surrounding plains, with limited investment in the port amid broader Kingdom priorities on taxation and defense, contributing to demographic and developmental inertia until later centuries.[44]Unification to World War II

Pescara integrated into the Kingdom of Italy following national unification in 1860, transitioning from Bourbon dominion in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies to the new centralized state.[45] The city's strategic Adriatic position facilitated its role in regional administration, though it remained a modest fortified settlement divided by the Pescara River into Pescara proper and Castellammare Adriatico. In 1927, under Fascist administrative reforms, the two adjacent municipalities merged to form the contemporary comune of Pescara, establishing it as a unified provincial capital and boosting its administrative coherence.[46] Early 20th-century expansion accelerated with improved infrastructure, particularly rail connections established in the late 19th century, including the opening of Pescara Porta Nuova station in 1883, which linked the city to broader Italian networks and stimulated trade, tourism, and population influx. Gabriele D'Annunzio, born in Pescara in 1863, exerted cultural influence as a native son and vanguard nationalist, his irredentist campaigns for territories like Fiume resonating locally to foster patriotic fervor amid Italy's prewar imperial ambitions.[47] During World War II, Pescara endured severe Allied aerial bombardment from 1943 to 1944, targeting rail junctions, the Pescara Dam, and supply routes to hinder German defenses on the Adriatic front and Gustav Line.[48] A notable raid on August 31, 1943, killed over 1,500 civilians, contributing to total wartime casualties exceeding 2,000.[49] By Allied liberation on June 10, 1944, approximately 80% of buildings lay destroyed or damaged, over 1,000 fully razed, obliterating the historic core and necessitating comprehensive postwar infrastructural overhaul.[50][51]Postwar Reconstruction and Modern Growth

Following World War II, Pescara faced extensive reconstruction after severe Allied bombings in 1943-1944 that destroyed much of its urban core, including the historic Pescara Vecchia district, prompting a shift toward modernist architecture and rapid infill development with concrete structures to accommodate returning residents and migrants.[52] By the 1950s, the city's population began surging due to internal migration from rural Abruzzo areas, drawn by emerging industrial opportunities and urban amenities, with the provincial population rising from approximately 200,000 in 1951 to over 300,000 by the 1970s as agricultural workers relocated to coastal hubs.[53] This era saw the demolition of surviving prewar buildings in favor of high-rise apartments and linear blocks, prioritizing density over preservation, which eroded the city's architectural heritage but enabled a tripling of the urban core's capacity to around 100,000 residents by 1981.[54] The 1980s and 1990s accelerated infrastructure expansion, including integration into the A14 Autostrada Adriatica motorway, with key Pescara segments completed by the mid-1970s and subsequent upgrades funded partly by national and later EU cohesion funds to enhance connectivity along the Adriatic coast.[55] These investments, including EU-supported urban development plans under programs like JESSICA, facilitated port expansions and road networks but contributed to unchecked sprawl, as peripheral greenfields converted to residential and commercial zones without stringent zoning, increasing built-up land by over 50% in central Italy's coastal regions from the 1950s to 2000.[56][57] While boosting accessibility, this pattern strained environmental carrying capacity, with fragmented development exacerbating flood risks in a low-lying Adriatic plain prone to subsidence. By 2023, the Pescara metropolitan area reached 382,000 inhabitants, reflecting sustained but slowing growth amid Italy's broader demographic stagnation, yet facing acute challenges from traffic congestion—evident in peak-hour delays averaging 20-30% above free-flow speeds on urban arterials—and housing shortages driven by high demand in the compact core versus sprawling suburbs.[2][56] Empirical assessments highlight how postwar haste prioritized quantity over resilient design, resulting in vulnerabilities like overburdened sewage systems and elevated per capita impervious surfaces, underscoring trade-offs in sustainability where rapid expansion outpaced integrated planning.[54]Demographics

Population Dynamics

As of 2023, the resident population of Pescara municipality stood at approximately 118,500 inhabitants.[1] The broader metropolitan area, encompassing surrounding urban territories, was estimated at 382,000 residents in 2023, with projections indicating growth to 385,000 by 2025 at annual rates of roughly 0.3%.[2] Post-World War II reconstruction drove significant population expansion, with the municipality growing from 37,966 residents recorded in the 1931 census to over 118,000 by the early 21st century, fueled by internal migration and economic development.[58] Growth peaked in the 1990s before tapering, with the 2021 census reporting 118,309 inhabitants and a modest annual change of -0.16% from 2011 to 2021 amid national economic pressures including the 2008 recession.[59] Demographic indicators reflect an aging profile, with a birth rate of 5.7 per 1,000 inhabitants and a death rate of 12.9 per 1,000, resulting in a negative natural balance that contributes to overall stabilization rather than expansion.[60] These rates, derived from ISTAT data, underscore lower fertility compared to the national Italian average of approximately 7.0 per 1,000 in recent years.[61]Ethnic and Cultural Composition

Pescara's population is predominantly ethnic Italian, comprising approximately 94.3% of residents as of January 1, 2023, with the native population primarily identifying with Abruzzo's regional heritage and speaking variants of the Abruzzese dialect, particularly the Adriatic subgroup prevalent in coastal areas like Pescara.[62][63] This dialect, influenced by Latin and southern Italian linguistic elements, reflects the area's historical isolation and cultural continuity, distinguishing it from standard Italian while maintaining strong ties to regional identity.[64] Foreign residents account for 5.7% of the city's population, totaling 6,736 individuals in 2023, with low naturalization rates consistent with national trends where citizenship acquisition remains limited among non-EU migrants.[62][65] The largest groups hail from Eastern Europe, including Romanians, Albanians, and Ukrainians, alongside smaller communities from North Africa and Asia, often concentrated in service and labor sectors.[62][66] Religiously, the population is overwhelmingly Roman Catholic, with estimates indicating over 97% adherence in the Archdiocese of Pescara-Penne, encompassing the city, underscoring the enduring influence of traditional Italian Catholicism on local customs and community life despite secularization pressures.[67] This composition supports the preservation of Abruzzo-specific cultural practices, such as dialect-based folklore and festivals, amid broader globalization.[68]Migration Patterns and Integration

Pescara has experienced net positive international migration since 2000, with the foreign resident population in the province rising from negligible levels to approximately 17,700 by recent estimates, representing 5.6% of the total population of around 316,000.[69] This influx, concentrated in the city and surrounding areas, has been primarily driven by labor demands in seasonal tourism, construction, and agriculture, sectors reliant on low-skilled migrant workers from Eastern Europe, North Africa, and South Asia.[70] Concurrently, significant outflows have occurred among native youth, with Abruzzo ranking high nationally for emigration of 18-34-year-olds seeking better opportunities in Rome, Milan, and abroad, exacerbating local demographic imbalances as educated locals depart for higher-wage urban centers.[71][72] Integration outcomes reveal persistent challenges, including elevated unemployment among migrants at roughly 15-20% compared to 8% for natives in Abruzzo as of 2023, attributable to skill mismatches, language barriers, and limited access to formal training programs.[73][74] National data indicate non-EU migrants face employment rates 10-15 percentage points below natives, a gap widened in regional economies like Pescara's where seasonal jobs predominate without pathways to stable integration.[75] Crime statistics show migrants overrepresented in petty offenses such as theft and public disorder, with Italian Interior Ministry figures reporting foreigners committing disproportionate shares relative to population size, though violent crime correlations remain debated and lower overall.[76] EU free-movement policies and asylum frameworks have facilitated unvetted entries into Italy, including Abruzzo, contributing to service strains in Pescara without commensurate fiscal contributions from low-integration cohorts, as evidenced by higher welfare dependency and housing pressures in coastal municipalities.[66] Local responses emphasize vocational programs and community policing, yet empirical metrics suggest assimilation lags, with limited upward mobility and cultural enclaves hindering broader societal cohesion.[77]Government and Administration

Local Governance Structure

Pescara operates under Italy's standard municipal governance framework as outlined in the Consolidated Law on Local Authorities (Testo Unico delle Leggi sull'Ordinamento degli Enti Locali, D.Lgs. 267/2000), featuring a directly elected mayor (sindaco) and city council (consiglio comunale) as primary organs, supported by an executive junta (giunta comunale).[78] The council comprises 33 members, including the mayor, responsible for legislative functions such as approving budgets, urban plans, and local regulations, while the mayor holds executive powers including policy implementation, public administration oversight, and representation of the comune.[79] As the provincial capital (capoluogo di provincia), Pescara's comune coordinates with the provincial administration on shared competencies like territorial planning, but maintains autonomous control over core local services including public utilities, social welfare, and infrastructure maintenance.[80] The current mayor, Carlo Masci, assumed office on June 10, 2019, following his election, and was re-elected on June 9-10, 2024, with 50.95% of the vote in the first round.[81][82] Masci, affiliated with center-right coalitions, leads the giunta, which executes council-approved policies through appointed assessors handling sectors like urban development, environment, and public works. Administrative operations emphasize decentralization, with services such as waste collection devolved to specialized entities like Ambiente S.p.A., a municipally controlled joint-stock company that manages integrated waste systems including door-to-door collection, achieving reported citizen satisfaction levels above regional averages due to operational responsiveness.[83] The municipal budget, approved annually by the council, reflects fiscal autonomy with revenues derived primarily from local sources including property taxes (IMU), waste service tariffs (TARI), and commercial levies, supplemented by state transfers and EU funds. For the 2023-2025 forecast period, current expenditures were projected at €125.2 million for 2024 alone, within a broader consolidated framework encompassing capital investments and debt servicing, underscoring reliance on efficient local revenue generation estimated at over half of total inflows.[84] This structure prioritizes operational efficiency, as evidenced by privatized or semi-autonomous service models yielding cost controls and service improvements compared to centralized state alternatives, though ongoing debates highlight risks of full privatization without guaranteed productivity gains.[85]Political Landscape and Elections

Pescara's municipal elections have shown a shift toward center-right dominance since the late 2010s, reflecting broader trends in Abruzzo amid national political fragmentation. In the 2019 communal elections held on May 26, Carlo Masci of the center-right coalition, supported by Forza Italia, Lega, Fratelli d'Italia, and other lists, secured victory in the first round with 51.3% of the vote, succeeding the center-left mayor Marco Alessandrini.[86][87] Voter turnout was approximately 60%, with key campaign issues including anti-corruption measures and pro-business policies contrasting environmental concerns raised by opponents.[88] Masci was re-elected in the June 2024 communal elections with 50.95% in the first round, again backed by a center-right alliance including Fratelli d'Italia and Forza Italia, defeating challengers from the center-left, Five Star Movement, and others.[89][82] This outcome underscored continued local preference for center-right governance, with critiques from the right targeting prior administrations' urban planning as contributing to overdevelopment and infrastructure strains. However, on June 25, 2025, the TAR of Abruzzo annulled results in 27 polling sections due to procedural irregularities, mandating a partial re-vote, which has introduced uncertainty to Masci's second term.[90][91] At the regional level, Pescara's voting patterns diverge somewhat from municipal trends. The 2019 Abruzzo regional election saw center-right candidate Marco Marsilio win with 48.03%, aligning with Pescara's communal shift, but in the 2024 regional vote on March 10, local ballots favored center-left challenger Luciano D'Amico with 50.85% against Marsilio's 49.15%, bucking the regional center-right victory of 53.5%.[92] These results highlight ideological tensions, with center-right emphasizing economic deregulation and anti-corruption—evident in Masci's platforms—against left-leaning priorities on environmental protection and social equity, amid turnout hovering around 60% in recent cycles.[93]Economy

Primary Sectors and Industries

The economy of Pescara is predominantly service-oriented, with the sector accounting for approximately 70% of employment, encompassing finance, retail, and wholesale trade activities that leverage the city's role as a regional commercial hub.[94] Manufacturing contributes around 15-20% of jobs, centered on small-scale operations in metalworking, mechanical engineering, and limited petrochemical processing, alongside fisheries supported by the Adriatic coastline.[95][96] In 2022, Pescara's GDP per capita stood at roughly €28,000, surpassing the Abruzzo regional average of €27,000 but trailing the national figure of approximately €35,000.[97][98] The port facilitates trade by handling about 330,000 tons of cargo annually, primarily bulk goods and industrial materials, underscoring Pescara's integration into regional supply chains.[99] Agriculture has diminished to under 5% of economic activity, reflecting a broader shift toward diversified manufacturing and nascent technology initiatives, bolstered by Abruzzo's Special Economic Zone incentives offering grants covering up to 90% of eligible investments for innovative projects.[100] These measures, active as of 2023, target sectors like digital and ecological transitions to foster firm growth in the province.[101]Tourism and Coastal Development

Pescara's tourism industry relies heavily on its 16-kilometer stretch of sandy beaches, which serve as the primary draw for domestic and regional visitors during the peak summer season from June to August. The local economy benefits from beach-related activities, including rentals, hospitality, and water sports, though precise revenue figures for Pescara specifically remain aggregated within Abruzzo's broader tourism data, which reported over 1.3 million arrivals region-wide in 2021. Post-2000 infrastructure enhancements along the Lungomare Cristoforo Colombo promenade, such as pedestrian walkways, cycling paths, and the 2009 opening of the Ponte del Mare bridge, have facilitated expanded hotel capacity and urban regeneration, with establishments like the Hotel Esplanade exemplifying seafront accommodations catering to tourists.[102][103] Cultural events bolster off-peak appeal, notably the Pescara Jazz Festival, established in 1969 as Italy's inaugural summer jazz gathering and held annually since 1981, featuring international artists and contributing to the city's reputation as a venue for live music amid coastal settings. Regional attractions, including the nearby Trabocchi Coast in southern Abruzzo—characterized by historic wooden fishing platforms (trabocchi) and sites like San Vito Chietino—extend day-trip opportunities, promoting eco-tourism and seafood experiences within a 30-40 minute drive from Pescara.[104][105][106] Despite these assets, tourism's seasonality drives economic volatility, with employment in hospitality and services surging in summer but contracting sharply afterward, mirroring patterns in Italy's Adriatic resorts where off-season job losses exceed 50% in comparable areas. Environmental concerns arise from intensified coastal development, including breakwaters and urban expansion that have altered beach morphology and increased erosion risks, as documented in studies of northern Adriatic shore protection efforts. Recent observations in 2025 highlight a 25% decline in beach visitors, attributed to unchanged pricing amid shifting preferences and broader Italian coastal tourism pressures, underscoring vulnerabilities to overtourism and sustainability gaps.[107][108]Economic Challenges and Reforms

Pescara, like much of Abruzzo, grapples with persistent youth unemployment, which stood at around 22-25% regionally in 2023, exceeding the national average and driving significant brain drain as educated young residents relocate northward or abroad in search of stable employment.[109][110] This exodus, part of Italy's broader loss of over 134 billion euros in human capital from 2011 to 2023 due to emigration of skilled workers, exacerbates labor shortages in local industries and hinders long-term growth.[111] Lingering public debt from expansive 1980s infrastructure projects—when Italy's national debt-to-GDP ratio surged from 54% in 1980 to over 100% by the early 1990s—continues to strain municipal finances, limiting investment in innovation and perpetuating fiscal rigidity.[112] Organized crime infiltration remains limited in Pescara compared to southern regions, though isolated 'Ndrangheta-linked activities, such as illicit waste disposal schemes in the 2010s, have posed risks to environmental and economic integrity.[113] Policy responses have emphasized market-oriented measures over reliance on EU structural funds, which, while bolstering Abruzzo's infrastructure post-eligibility for Objective 1 status, have drawn criticism for fostering dependency rather than self-sustaining development.[114] Recent initiatives, including aspects of Italy's National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR) post-2020, have aimed to streamline regulations and attract foreign direct investment, with regional FDI inflows showing modest recovery amid national trends.[115] Private sector efforts, such as fishing cooperatives in Pescara's port, demonstrate efficacy in boosting productivity; studies on Italian cooperatives indicate efficiency gains through collective resource management, contrasting with subsidy-driven models prone to inefficiency.[116] These reforms prioritize deregulation and entrepreneurial incentives, evidenced by stabilized local outputs in fisheries despite national challenges, underscoring causal links between reduced state intervention and enhanced yields.[117]Culture and Heritage

Festivals and Traditions

The Pescara Jazz Festival, inaugurated in 1969, occurs annually in July and holds the distinction of being Italy's inaugural summer event dedicated exclusively to jazz music. It presents concerts by prominent Italian and international performers across urban venues, contributing to the city's contemporary cultural profile amid its coastal setting.[118][119] The primary religious tradition centers on the feast of San Cetteo, Pescara's patron saint and bishop of Amiterno, celebrated from October 8 to 10 with eucharistic masses, processions of the saint's statue along the waterfront, and communal gatherings at the Cathedral of San Cetteo. This event traces to historical fishermen's boat processions commemorating the saint's martyrdom by the Aterno River, reflecting the locale's enduring ties to maritime and agrarian roots.[120] Carnival observances in Pescara incorporate masked parties and social events in February or March, echoing Abruzzo's hybrid pagan-Christian customs that emphasize communal revelry and satire prior to Lent. Additional religious processions honor other saints, such as annual boat marches from the port on the last Sunday in November for San Andrea, preserving seafaring rituals amid seasonal tourism.[121][122] Customs like the ritual grilling of arrosticini—small skewers of sheep meat cooked over open coals—feature prominently at these gatherings, symbolizing Abruzzese pastoral heritage without elaborate preparation, often shared informally to foster social bonds. Such practices face tensions between authentic transmission and event-driven commercialization, as larger festivals draw visitors but risk diluting localized observances.[123][124]Cuisine and Local Products

Pescara's cuisine centers on fresh Adriatic seafood, leveraging the city's role as a major fishing port. The emblematic brodetto alla pescarese is a hearty stew of mixed fish such as scorpionfish, mullet, and sole, simmered with tomatoes, garlic, olive oil, and peperoncino for a spicy, tomato-based broth, traditionally served with grilled bread.[125][126] This dish exemplifies the simplicity and quality of local catches, with preparation emphasizing minimal intervention to highlight natural flavors.[127] Among agricultural products, Montepulciano d'Abruzzo red wine holds DOC status since 1969, produced from grapes grown in the region's hilly terroir, yielding robust, cherry-scented varietals with moderate tannins. Abruzzo's overall wine exports, dominated by Montepulciano, totaled €197.9 million in 2024, reflecting a +18.1% annual increase driven by demand in key markets like the United States.[128] Arrosticini, small skewers of cubed sheep or lamb meat grilled over open coals without seasoning beyond salt, trace to Abruzzo's transhumance traditions and remain a staple in Pescara eateries, consumed in dozens for communal meals.[129][130] The area's fisheries operate under EU Common Fisheries Policy quotas aimed at stock sustainability, with ongoing reforms enforcing total allowable catches to prevent overexploitation in the Adriatic.[131] Local adherence to a seafood-rich, vegetable-heavy diet akin to the Mediterranean pattern aligns with Abruzzo's demographic longevity, as cross-sectional studies of regional nonagenarians and centenarians link such habits—emphasizing early dinners and caloric moderation—to extended lifespans beyond national averages.[132][133]Literary and Artistic Contributions

Pescara served as the birthplace of Gabriele D'Annunzio on March 12, 1863, establishing the city as a focal point for Italian literary heritage tied to his prolific output in poetry, novels, and drama.[134] D'Annunzio's Decadent style, blending sensualism and nationalism, permeated local cultural narratives, with Pescara officially designating itself the "Città di Gabriele D'Annunzio" in 2020 to honor his enduring legacy.[135] His works, including early collections like Primo Vere published in 1879, drew from Abruzzese roots and influenced subsequent regional aesthetics toward expressive modernism.[136] Artistic institutions in Pescara preserve and extend these traditions through dedicated museums. The Museo delle Genti d'Abruzzo, housed in a former Bourbon fortress since its founding in 1990, exhibits over 13 themed rooms chronicling Abruzzo's ethnographic evolution, including artisanal crafts and sculptural works by local figures like Giuseppe Di Prinzio.[137] Complementing this, the Museo Civico Basilio Cascella displays paintings and graphics by the Abruzzese artist Basilio Cascella (1890–1983), emphasizing post-Impressionist techniques rooted in regional landscapes.[138] Contemporary contributions include vibrant street art initiatives, with Italian artist Millo creating expansive murals such as the 2017 "Dream" piece along Pescara's urban corridors, integrating historical motifs with modern abstraction to revitalize public spaces.[139] In film, the Scrittura e Immagine Short Film Festival, launched in the late 1990s and reaching its 26th edition in 2025, fosters intersections of literature and visual storytelling, attracting international shorts that explore narrative innovation.[140] These efforts highlight Pescara's shift toward multimedia arts while grounding in D'Annunzio-inspired vitality.Education and Research

Higher Education Institutions

The Università degli Studi "Gabriele d'Annunzio" Chieti-Pescara maintains a significant campus in Pescara, hosting departments focused on engineering, economics, management, and architecture, which support regional innovation in technical and business sectors.[141] Established in 1965 as a non-state university and achieving full public status in 1982, the institution spans two campuses with 13 departments and enrolls approximately 25,000 to 36,000 students across programs, many commuting to or residing in Pescara for specialized courses.[142][143] These offerings emphasize practical applications, including engineering disciplines that align with Abruzzo's industrial needs and economics programs fostering entrepreneurial skills.[144] Research activities at the Pescara campus contribute to local innovation through outputs in applied sciences, though specific metrics like annual publications exceed hundreds in collaborative fields such as engineering and health-related studies.[145] The university's emphasis on interdisciplinary projects has yielded patents and spin-offs, particularly in technology transfer, aiding Pescara's transition toward knowledge-based industries despite limited public data on biotech-specific advancements.[146] Graduation rates hover around 60-70% within standard timelines, influenced by Italy's broader higher education challenges like funding constraints, with Pescara's programs showing lower dropout rates of about 15% compared to national averages.[147] The student body drives economic activity in Pescara, with enrollment supporting local commerce through housing, retail, and services, estimated to generate substantial spending though precise figures remain undocumented in recent analyses.[148] However, rapid growth strains infrastructure, including overcrowded facilities and transportation, prompting calls for expanded investments to sustain innovation contributions without exacerbating urban pressures.[149] No other independent universities operate primarily in Pescara, positioning G. d'Annunzio as the dominant force in higher education and regional human capital development.Scientific and Cultural Facilities

Pescara's cultural landscape includes dedicated institutions for art preservation and public engagement. The Museo d'Arte Moderna Vittoria Colonna, operational since 2002, houses a collection of 20th-century works by Italian and international artists, including pieces by Renato Guttuso, Joan Miró, and Pablo Picasso, displayed in a central location near the seafront.[150][151] The museum offers free general admission, with paid exhibitions, and operates Tuesday to Saturday from 9:00 to 13:00, extending afternoons on select days.[152] The Aurum La Fabbrica delle Idee functions as a repurposed early 20th-century distillery building, now a cultural hub in the Pineta D'Annunziana area, hosting art exhibitions, live performances, conferences, and events that promote local heritage and contemporary creativity.[153][154] Its Liberty-Neoclassical architecture underscores Pescara's industrial past while serving modern cultural programming.[155] Scientific facilities independent of universities are limited, with regional research often channeled through national agencies like ENEA, which advances renewable technologies but lacks Pescara-specific labs documented in public records.[156] Pescara's coastal position supports potential in wind energy studies, given average annual wind speeds of approximately 3.5-4 meters per second, though dedicated non-academic labs remain underdeveloped.[28] Critics of public funding models argue that monopolistic state support hampers efficiency compared to private endowments, potentially stifling innovation in such fields, as noted in broader Italian economic analyses.[157]Sports and Recreation

Professional Sports Teams

Delfino Pescara 1936 is the city's principal professional football club, founded in 1936 and currently competing in Serie B following promotion from Serie C via playoffs on June 8, 2025.[158] The team has secured Serie B titles twice and Serie C championships twice, with notable promotions to Serie A including the 1976–77 season as Abruzzo's first top-flight representative and the 2011–12 campaign under Zdeněk Zeman's high-pressing style.[159] Overall, Pescara has contested seven Serie A seasons, though relegations have followed each, underscoring challenges in sustaining elite-level performance amid regional economic constraints.[160] The club plays at Stadio Adriatico – Giovanni Cornacchia, which holds a capacity of 20,367 following renovations that reduced it from prior highs of around 40,000 for safety and modern standards.[161] Average match attendance hovers in the mid-thousands during Serie B play, reflecting dedicated local support in a province of about 300,000 despite competition from larger Italian clubs.[162] Pescara Basket represents the city in lower-tier professional basketball, competing in Serie B Interregionale with a roster emphasizing regional talent development.[163] The team maintains blue-and-white colors akin to the football club but operates without the same national prominence, focusing on Serie B-level competition rather than higher divisions like Serie A2.[164] No major doping controversies have directly implicated Pescara's organized team structures, though individual athletes from the Abruzzo region, such as cyclist Danilo Di Luca, faced suspensions in the 2000s for violations unrelated to club governance.[165]Outdoor and Beach Activities

Pescara's Adriatic coastline features long stretches of sandy beaches that support a range of water-based and shoreline activities, including swimming, sunbathing, and beach volleyball. Public beaches like Spiaggia di Pescara provide dedicated courts for volleyball, alongside facilities for kite surfing and windsurfing, drawn by consistent coastal winds.[13] These pursuits are popular among locals and seasonal visitors, contributing to the city's reputation as a recreational hub during summer months.[166] Cycling is facilitated by the lungomare promenades, such as Lungomare Matteotti and Lungomare Papa Giovanni XXIII, which include dedicated bike paths running parallel to the shore. These paths connect with the regional Bike to Coast route, a 131-kilometer coastal trail passing through Pescara, enabling extended rides with sea views.[167][168] Sport fishing draws enthusiasts to the area, with events like the annual Pescare Show trade fair showcasing gear and techniques, and the Dolphin Club hosting international big game championships, such as the 30th World Championship in 2022.[169][170] The prevalence of these outdoor activities aligns with Abruzzo's lower-than-average obesity rates, with regional studies reporting childhood obesity at approximately 6% and overweight at 21% among adolescents, potentially linked to higher physical activity levels compared to national figures of 10-11% adult obesity.[171][172] However, peak summer periods, particularly July and August, bring significant crowds to the beaches, with high attendance straining space on weekends and during holidays, though Pescara remains less overrun than more tourist-heavy Italian resorts.[106][173]Infrastructure and Transportation

Road Networks and Motorways

The A14 Autostrada Adriatica serves as the principal motorway artery for Pescara, extending northward approximately 400 kilometers to Bologna and southward over 300 kilometers to Bari and Taranto along Italy's Adriatic coast. Operated under concession by Autostrade per l'Italia S.p.A., a private entity regulated by the Italian government, the A14 provides direct highway access to Pescara via multiple interchanges, including Pescara Ovest-Chieti, Pescara Centrale, and Pescara Nord-Città Sant'Angelo, which connect to local state roads (strade statali) like the SS16 Adriatica. This network supports regional commerce and tourism, with the concession model enabling toll revenues to fund maintenance and upgrades, though overall system-wide toll income for Autostrade per l'Italia reached €881 million in the first quarter of 2025 alone across its 3,000-plus kilometers.[174][175][176] Urban road segments integrated with A14 access points experience notable congestion, with 2024 average speeds across Pescara's road network recorded at 32.5 km/h, dropping to 27-30 km/h during peak rush hours (37-49% congestion). Ongoing expansion works, such as those near Pescara Nord-Città Sant'Angelo and Pescara Ovest-Chieti, have led to frequent queues exceeding 1 km, attributed to construction for safety and capacity improvements under Autostrade per l'Italia's investment plan. These private-led initiatives contrast with slower state-managed projects elsewhere in Italy, where bureaucratic delays in permitting and funding have historically protracted infrastructure timelines, though specific A14 Pescara expansions proceed via concession-mandated timelines tied to traffic risk-sharing mechanisms.[177][178][179][180]Abruzzo Airport

Abruzzo Airport (IATA: PSR, ICAO: LIBP), located about 4 kilometers west of Pescara's city center in the locality of Pretoro, functions as the principal air hub for the Abruzzo region and surrounding areas including parts of Molise and Marche.[181] The facility operates a single asphalt runway (04/22) measuring 2,418 meters in length and 45 meters in width, supporting scheduled passenger flights primarily by narrow-body jets from low-cost carriers.[182] In 2023, it handled 872,701 passengers, reflecting a 21.9% year-on-year increase attributed to expanded low-cost operations and seasonal tourism demand.[183] Ryanair, the airport's dominant operator, established a base there in 2022 with one Boeing 737 aircraft, facilitating up to 15 routes including destinations in the UK, Germany, and Belgium; the carrier announced plans for a second based aircraft in summer 2025 to support over 120 weekly flights.[184] [185] This expansion has driven route diversification, with Ryanair connecting Pescara to 16 European cities in summer 2024 alone.[186] Cargo handling remains modest compared to passenger traffic, aligning with the airport's regional focus rather than major freight volumes seen at larger Italian hubs.[187] Ongoing infrastructure developments include proposals endorsed by Italy's Civil Aviation Authority (ENAC) in 2019 to extend the runway by 300 meters to 2,700 meters, potentially accommodating wider-body aircraft and enhancing operational capacity amid rising demand.[188] The airport adheres to noise abatement procedures outlined in Italian AIP guidelines, though localized concerns persist due to its proximity to residential areas and coastal wetlands that may elevate bird strike risks, as is common in avian-rich environments near European regional airports.[189]Port Facilities

The Port of Pescara functions primarily as a regional commercial and passenger facility on Italy's Adriatic coast, accommodating around 170 vessel calls annually with a cargo throughput of approximately 330,000 tons.[99] It handles mainly bulk goods such as diesel, petrol derivatives, and coils, alongside limited general cargo, reflecting its role in supporting local industrial and agricultural exports from Abruzzo.[99] Passenger services include seasonal ferry routes operated by SNAV to Croatian destinations like Split and Hvar (Stari Grad), with sailings concentrated in summer months and journey times of 4.5 to 5 hours.[190] These foot-passenger-only vessels cater to tourism flows but do not carry vehicles or pets.[191] The integrated Marina di Pescara offers 1,000 berths for yachts up to 50 meters in length and 3 meters draft, equipped with utilities including water, electricity, and maintenance services across a 107,000 square meter water basin.[192] Siltation from the adjacent Pescara River necessitates periodic dredging to maintain navigable depths; in September 2025, works valued at €2 million commenced to address sedimentation issues.[193] Operated under the Central Adriatic Ports Authority, which also manages the larger Port of Ancona, Pescara's infrastructure supports supplementary regional maritime traffic rather than competing directly in high-volume international trade.[194]Rail Connections

Pescara is connected to the national rail network primarily through Ferrovie dello Stato Italiane (FS), operating via its subsidiaries Trenitalia for passenger services and Rete Ferroviaria Italiana (RFI) for infrastructure. The city lies on the Adriatic railway line, extending from Rimini to Bari and beyond to Lecce, facilitating east-west coastal travel. Additionally, the Rome–Sulmona–Pescara line provides transversal connectivity to central Italy, linking Pescara to Rome via Sulmona and Avezzano.[195][196] Pescara Centrale serves as the principal station, handling approximately 3.5 million passengers annually and accommodating regional, intercity, and some high-speed services. Direct Trenitalia trains operate to Rome Termini, with journeys averaging 3 hours and 20 minutes over 156 km, though upgrades aim to reduce this to about 2 hours. To Bari Centrale, services cover 265 km in around 3 hours, supported by ongoing track-doubling projects between Pescara and Bari to enhance capacity and reliability.[197][198][199] Efforts to develop high-speed capabilities on the Rome-Pescara line have progressed intermittently, with partial public funding allocated, including from the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP). Construction resumed in April 2025 for upgrades, including electrification enhancements and track improvements, but full high-speed implementation remains stalled by funding constraints and bureaucratic delays, despite appointments of governmental commissioners to expedite works. The Adriatic line sections serving Pescara have been electrified since the mid-20th century, enabling electric traction for most services.[195][200][201] Rail services in Pescara, dominated by state-owned FS, face punctuality issues typical of the Italian network, where high-speed Frecciarossa trains arrive late in 31% of cases on monitored routes. The Italian Competition Authority has investigated RFI for alleged abuse of dominant position, including delays in granting infrastructure access to potential entrants, effectively preserving FS's monopoly on regional and many intercity routes despite EU liberalization directives. Private operators like Italo compete mainly on northern high-speed corridors but have limited presence in Abruzzo, highlighting critiques of state obstructionism that hinder competition and service improvements compared to privatized models elsewhere.[202][203][204]Public Transit Systems