Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

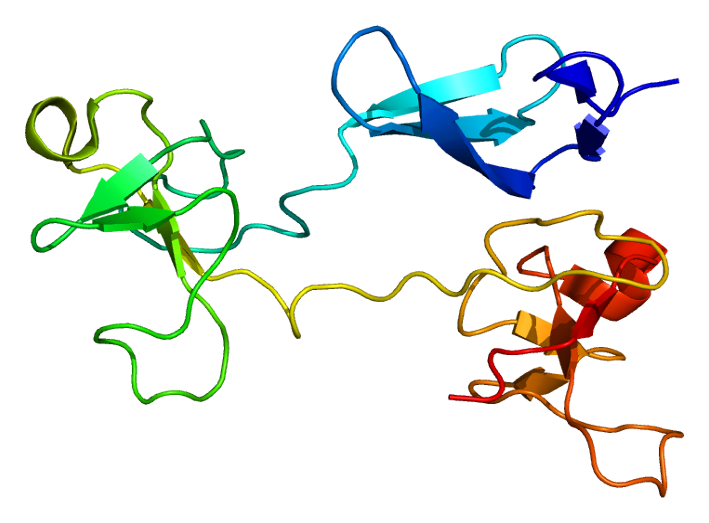

Fibronectin

View on Wikipedia

Fibronectin is a high-molecular weight (~500-~600 kDa)[5] glycoprotein of the extracellular matrix that binds to membrane-spanning receptor proteins called integrins.[6] Fibronectin also binds to other extracellular matrix proteins such as collagen, fibrin, and heparan sulfate proteoglycans (e.g. syndecans).

Fibronectin exists as a protein dimer, consisting of two nearly identical monomers linked by a pair of disulfide bonds.[6] The fibronectin protein is produced from a single gene, but alternative splicing of its pre-mRNA leads to the creation of several isoforms.

Two types of fibronectin are present in vertebrates:[6]

- soluble plasma fibronectin (formerly called "cold-insoluble globulin", or CIg) is a major protein component of blood plasma (300 μg/ml) and is produced in the liver by hepatocytes.

- insoluble cellular fibronectin is a major component of the extracellular matrix. It is secreted by various cells, primarily fibroblasts, as a soluble protein dimer and is then assembled into an insoluble matrix in a complex cell-mediated process.

Fibronectin plays a major role in cell adhesion, growth, migration, and differentiation, and it is important for processes such as wound healing and embryonic development.[6] Altered fibronectin expression, degradation, and organization has been associated with a number of pathologies, including cancer, arthritis, and fibrosis.[7][8]

Structure

[edit]Fibronectin exists as a protein dimer, consisting of two nearly identical polypeptide chains linked by a pair of C-terminal disulfide bonds.[9] Each fibronectin subunit has a molecular weight of ~230–~275 kDa[10] and contains multiple copies of three types of modules: type I, II, and III. All three modules are composed of two anti-parallel β-sheets resulting in a Beta-sandwich; however, type I and type II are stabilized by intra-chain disulfide bonds, while type III modules do not contain any disulfide bonds. The absence of disulfide bonds in type III modules allows them to partially unfold under applied force.[11]

Three regions of variable splicing occur along the length of the fibronectin protomer. One or both of the "extra" type III modules (EIIIA and EIIIB) may be present in cellular fibronectin, but they are never present in plasma fibronectin. A "variable" V-region exists between III14–15 (the 14th and 15th type III module). The V-region structure is different from the type I, II, and III modules, and its presence and length may vary. The V-region contains the binding site for α4β1 integrins. It is present in most cellular fibronectin, but only one of the two subunits in a plasma fibronectin dimer contains a V-region sequence.

The modules are arranged into several functional and protein-binding domains along the length of a fibronectin monomer. There are four fibronectin-binding domains, allowing fibronectin to associate with other fibronectin molecules.[9] One of these fibronectin-binding domains, I1–5, is referred to as the "assembly domain", and it is required for the initiation of fibronectin matrix assembly. Modules III9–10 correspond to the "cell-binding domain" of fibronectin. The RGD sequence (Arg–Gly–Asp) is located in III10 and is the site of cell attachment via α5β1 and αVβ3 integrins on the cell surface. The "synergy site" is in III9 and has a role in modulating fibronectin's association with α5β1 integrins.[12] Fibronectin also contains domains for fibrin-binding (I1–5, I10–12), collagen-binding (I6–9), fibulin-1-binding (III13–14), heparin-binding and syndecan-binding (III12–14).[9]

Function

[edit]Fibronectin has numerous functions that ensure the normal functioning of vertebrate organisms.[6] It is involved in cell adhesion, growth, migration, and differentiation. Cellular fibronectin is assembled into the extracellular matrix, an insoluble network that separates and supports the organs and tissues of an organism.

Fibronectin plays a crucial role in wound healing.[13][14] Along with fibrin, plasma fibronectin is deposited at the site of injury, forming a blood clot that stops bleeding and protects the underlying tissue. As repair of the injured tissue continues, fibroblasts and macrophages begin to remodel the area, degrading the proteins that form the provisional blood clot matrix and replacing them with a matrix that more resembles the normal, surrounding tissue. Fibroblasts secrete proteases, including matrix metalloproteinases, that digest the plasma fibronectin, and then the fibroblasts secrete cellular fibronectin and assemble it into an insoluble matrix. Fragmentation of fibronectin by proteases has been suggested to promote wound contraction, a critical step in wound healing. Fragmenting fibronectin further exposes its V-region, which contains the site for α4β1 integrin binding. These fragments of fibronectin are believed to enhance the binding of α4β1 integrin-expressing cells, allowing them to adhere to and forcefully contract the surrounding matrix.

Fibronectin is necessary for embryogenesis, and inactivating the gene for fibronectin results in early embryonic lethality.[15] Fibronectin is important for guiding cell attachment and migration during embryonic development. In mammalian development, the absence of fibronectin leads to defects in mesodermal, neural tube, and vascular development. Similarly, the absence of a normal fibronectin matrix in developing amphibians causes defects in mesodermal patterning and inhibits gastrulation.[16]

Fibronectin is also found in normal human saliva, which helps prevent colonization of the oral cavity and pharynx by pathogenic bacteria.[17]

Matrix assembly

[edit]Cellular fibronectin is assembled into an insoluble fibrillar matrix in a complex cell-mediated process.[18] Fibronectin matrix assembly begins when soluble, compact fibronectin dimers are secreted from cells, often fibroblasts. These soluble dimers bind to α5β1 integrin receptors on the cell surface and aid in clustering the integrins. The local concentration of integrin-bound fibronectin increases, allowing bound fibronectin molecules to more readily interact with one another. Short fibronectin fibrils then begin to form between adjacent cells. As matrix assembly proceeds, the soluble fibrils are converted into larger insoluble fibrils that comprise the extracellular matrix.

Fibronectin's shift from soluble to insoluble fibrils proceeds when cryptic fibronectin-binding sites are exposed along the length of a bound fibronectin molecule. Cells are believed to stretch fibronectin by pulling on their fibronectin-bound integrin receptors. This force partially unfolds the fibronectin ligand, unmasking cryptic fibronectin-binding sites and allowing nearby fibronectin molecules to associate. This fibronectin-fibronectin interaction enables the soluble, cell-associated fibrils to branch and stabilize into an insoluble fibronectin matrix.

A transmembrane protein, CD93, has been shown to be essential for fibronectin matrix assembly (fibrillogenesis) in human dermal blood endothelial cells.[19] As a consequence, knockdown of CD93 in these cells resulted in the disruption of the fibronectin fibrillogenesis. Moreover, the CD93 knockout mice retinas displayed disrupted fibronectin matrix at the retinal sprouting front.[19]

Role in cancer

[edit]Several morphological changes has been observed in tumors and tumor-derived cell lines that have been attributed to decreased fibronectin expression, increased fibronectin degradation, and/or decreased expression of fibronectin-binding receptors, such as α5β1 integrins.[20]

Fibronectin has been implicated in carcinoma development.[21] In lung carcinoma, fibronectin expression is increased especially in non-small cell lung carcinoma. The adhesion of lung carcinoma cells to fibronectin enhances tumorigenicity and confers resistance to apoptosis-inducing chemotherapeutic agents. Fibronectin has been shown to stimulate the gonadal steroids that interact with vertebrate androgen receptors, which are capable of controlling the expression of cyclin D and related genes involved in cell cycle control. These observations suggest that fibronectin may promote lung tumor growth/survival and resistance to therapy, and it could represent a novel target for the development of new anticancer drugs.

Fibronectin 1 acts as a potential biomarker for radioresistance[22] and for pan-cancer prognosis.[23]

FN1-FGFR1 fusion is frequent in phosphaturic mesenchymal tumours.[24][25]

Role in wound healing

[edit]Fibronectin has profound effects on wound healing, including the formation of proper substratum for migration and growth of cells during the development and organization of granulation tissue, as well as remodeling and resynthesis of the connective tissue matrix.[26] The biological significance of fibronectin in vivo was studied during the mechanism of wound healing.[26] Plasma fibronectin levels are decreased in acute inflammation or following surgical trauma and in patients with disseminated intravascular coagulation.[27]

Fibronectin is located in the extracellular matrix of embryonic and adult tissues (not in the basement membranes of the adult tissues), but may be more widely distributed in inflammatory lesions. During blood clotting, the fibronectin remains associated with the clot, covalently cross-linked to fibrin with the help of Factor XIII (fibrin-stabilizing factor).[28][29] Fibroblasts play a major role in wound healing by adhering to fibrin. Fibroblast adhesion to fibrin requires fibronectin, and was strongest when the fibronectin was cross-linked to the fibrin. Patients with Factor XIII deficiencies display impairment in wound healing as fibroblasts don't grow well in fibrin lacking Factor XIII. Fibronectin promotes particle phagocytosis by both macrophages and fibroblasts. Collagen deposition at the wound site by fibroblasts takes place with the help of fibronectin. Fibronectin was also observed to be closely associated with the newly deposited collagen fibrils. Based on the size and histological staining characteristics of the fibrils, it is likely that at least in part they are composed of type III collagen (reticulin). An in vitro study with native collagen demonstrated that fibronectin binds to type III collagen rather than other types.[30]

Fibronectin genetic variation as a protective factor against Alzheimer's disease

[edit]A specific genetic variation in Fibronectin gene was shown to reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease in a multicenter, multiethnic genetic epidemiology and functional genomics study. This effect is believed to be through enhancing the brain's ability to clear the toxic waste and protein accumulation through the blood–brain barrier.[31]

Interactions

[edit]Besides integrin, fibronectin binds to many other host and non-host molecules. For example, it has been shown to interact with proteins such fibrin, tenascin, TNF-α, BMP-1, rotavirus NSP-4, and many fibronectin-binding proteins from bacteria (like FBP-A; FBP-B on the N-terminal domain), as well as the glycosaminoglycan, heparan sulfate.

pUR4 is a recombinant peptide that is known to inhibit the polymerization of fibronectin in a number of cell types including fibroblasts and endothelial cells.[32]

Fibronectin has been shown to interact with:

See also

[edit]- Fetal fibronectin

- Fibronectin type I domain

- Fibronectin type II domain

- Fibronectin type III domain

- Monobody, an engineered antibody mimetic based on the structure of the fibronectin type III domain

- Substrate adhesion molecules

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000115414 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000026193 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Mitrović S, Mitrović D, Todorović V (July 1995). "[Fibronectin--a multifunctional glycoprotein]". Srpski Arhiv Za Celokupno Lekarstvo. 123 (7–8): 198–201. PMID 17974429.

- ^ a b c d e Pankov R, Yamada KM (October 2002). "Fibronectin at a glance". Journal of Cell Science. 115 (Pt 20): 3861–3. doi:10.1242/jcs.00059. PMID 12244123.

- ^ Williams CM, Engler AJ, Slone RD, Galante LL, Schwarzbauer JE (May 2008). "Fibronectin expression modulates mammary epithelial cell proliferation during acinar differentiation". Cancer Research. 68 (9): 3185–92. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2673. PMC 2748963. PMID 18451144.

- ^ Kragstrup TW, Sohn DH, Lepus CM, Onuma K, Wang Q, Robinson WH, et al. (2019). "Fibroblast-like synovial cell production of extra domain A fibronectin associates with inflammation in osteoarthritis". BMC Rheumatology. 3 46. doi:10.1186/s41927-019-0093-4. PMC 6886182. PMID 31819923.

- ^ a b c Mao Y, Schwarzbauer JE (September 2005). "Fibronectin fibrillogenesis, a cell-mediated matrix assembly process". Matrix Biology. 24 (6): 389–99. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2005.06.008. PMID 16061370.

- ^ Sitterley G. "Fibronectin". Sigma Aldrich.

- ^ Erickson HP (2002). "Stretching fibronectin". Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 23 (5–6): 575–80. doi:10.1023/A:1023427026818. PMID 12785106. S2CID 7052723.

- ^ Sechler JL, Corbett SA, Schwarzbauer JE (December 1997). "Modulatory roles for integrin activation and the synergy site of fibronectin during matrix assembly". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 8 (12): 2563–73. doi:10.1091/mbc.8.12.2563. PMC 25728. PMID 9398676.

- ^ Grinnell F (1984). "Fibronectin and wound healing". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 26 (2): 107–116. doi:10.1002/jcb.240260206. PMID 6084665. S2CID 28645109.

- ^ Valenick LV, Hsia HC, Schwarzbauer JE (September 2005). "Fibronectin fragmentation promotes alpha4beta1 integrin-mediated contraction of a fibrin-fibronectin provisional matrix". Experimental Cell Research. 309 (1): 48–55. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.05.024. PMID 15992798.

- ^ George EL, Georges-Labouesse EN, Patel-King RS, Rayburn H, Hynes RO (December 1993). "Defects in mesoderm, neural tube and vascular development in mouse embryos lacking fibronectin". Development. 119 (4): 1079–91. doi:10.1242/dev.119.4.1079. PMID 8306876.

- ^ Darribère T, Schwarzbauer JE (April 2000). "Fibronectin matrix composition and organization can regulate cell migration during amphibian development". Mechanisms of Development. 92 (2): 239–50. doi:10.1016/S0925-4773(00)00245-8. PMID 10727862. S2CID 2640979.

- ^ Hasty DL, Simpson WA (September 1987). "Effects of fibronectin and other salivary macromolecules on the adherence of Escherichia coli to buccal epithelial cells". Infection and Immunity. 55 (9): 2103–9. doi:10.1128/IAI.55.9.2103-2109.1987. PMC 260663. PMID 3305363.

- ^ Wierzbicka-Patynowski I, Schwarzbauer JE (August 2003). "The ins and outs of fibronectin matrix assembly". Journal of Cell Science. 116 (Pt 16): 3269–76. doi:10.1242/jcs.00670. PMID 12857786. S2CID 16975447.

- ^ a b Lugano R, Vemuri K, Yu D, Bergqvist M, Smits A, Essand M, et al. (August 2018). "CD93 promotes β1 integrin activation and fibronectin fibrillogenesis during tumor angiogenesis". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 128 (8): 3280–3297. doi:10.1172/JCI97459. PMC 6063507. PMID 29763414.

- ^ Hynes, Richard O. (1990). Fibronectins. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-97050-9.

- ^ Han S, Khuri FR, Roman J (January 2006). "Fibronectin stimulates non-small cell lung carcinoma cell growth through activation of Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin/S6 kinase and inactivation of LKB1/AMP-activated protein kinase signal pathways". Cancer Research. 66 (1): 315–23. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2367. PMID 16397245.

- ^ Jerhammar F, Ceder R, Garvin S, Grénman R, Grafström RC, Roberg K (December 2010). "Fibronectin 1 is a potential biomarker for radioresistance in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma". Cancer Biology & Therapy. 10 (12): 1244–1251. doi:10.4161/cbt.10.12.13432. PMID 20930522.

- ^ Chicco D, Alameer A, Rahmati S, Jurman G (November 2022). "Towards a potential pan-cancer prognostic signature for gene expression based on probesets and ensemble machine learning". BioData Mining. 15 (1) 28. doi:10.1186/s13040-022-00312-y. eISSN 1756-0381. PMC 9632055. PMID 36329531.

- ^ Wasserman JK, Purgina B, Lai CK, Gravel D, Mahaffey A, Bell D, et al. (January 2016). "Phosphaturic Mesenchymal Tumor Involving the Head and Neck: A Report of Five Cases with FGFR1 Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization Analysis". Head and Neck Pathology. 10 (3): 279–85. doi:10.1007/s12105-015-0678-1. PMC 4972751. PMID 26759148.

- ^ Lee JC, Jeng YM, Su SY, Wu CT, Tsai KS, Lee CH, et al. (March 2015). "Identification of a novel FN1-FGFR1 genetic fusion as a frequent event in phosphaturic mesenchymal tumour". The Journal of Pathology. 235 (4): 539–45. doi:10.1002/path.4465. PMID 25319834. S2CID 9887919.

- ^ a b Grinnell F, Billingham RE, Burgess L (March 1981). "Distribution of fibronectin during wound healing in vivo". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 76 (3): 181–189. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12525694. PMID 7240787.

- ^ Bruhn HD, Heimburger N (1976). "Factor-VIII-related antigen and cold-insoluble globulin in leukemias and carcinomas". Haemostasis. 5 (3): 189–192. doi:10.1159/000214134. PMID 1002003.

- ^ Mosher DF (August 1975). "Cross-linking of cold-insoluble globulin by fibrin-stabilizing factor". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 250 (16): 6614–6621. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)41110-1. PMID 1158872.

- ^ Mosher DF (March 1976). "Action of fibrin-stabilizing factor on cold-insoluble globulin and alpha2-macroglobulin in clotting plasma". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 251 (6): 1639–1645. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)33696-7. PMID 56335.

- ^ Engvall E, Ruoslahti E, Miller EJ (June 1978). "Affinity of fibronectin to collagens of different genetic types and to fibrinogen". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 147 (6): 1584–1595. doi:10.1084/jem.147.6.1584. PMC 2184308. PMID 567240.

- ^ Bhattarai P, Gunasekaran TI, Belloy ME, Reyes-Dumeyer D, Jülich D, Tayran H, et al. (April 2024). "Rare genetic variation in fibronectin 1 (FN1) protects against APOEε4 in Alzheimer's disease". Acta Neuropathologica. 147 (1) 70. doi:10.1007/s00401-024-02721-1. PMC 11006751. PMID 38598053.

- ^ Chiang, H. Y., Korshunov, V. A., Serour, A., Shi, F., and Sottile, J. “Fibronectin is an important regulator of flow-induced vascular remodeling.” Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 29, 1074-9 (2009).

- ^ Jalkanen S, Jalkanen M (February 1992). "Lymphocyte CD44 binds the COOH-terminal heparin-binding domain of fibronectin". The Journal of Cell Biology. 116 (3): 817–25. doi:10.1083/jcb.116.3.817. PMC 2289325. PMID 1730778.

- ^ Lapiere JC, Chen JD, Iwasaki T, Hu L, Uitto J, Woodley DT (November 1994). "Type VII collagen specifically binds fibronectin via a unique subdomain within the collagenous triple helix". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 103 (5): 637–41. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12398270. PMID 7963647.

- ^ Chen M, Marinkovich MP, Veis A, Cai X, Rao CN, O'Toole EA, et al. (June 1997). "Interactions of the amino-terminal noncollagenous (NC1) domain of type VII collagen with extracellular matrix components. A potential role in epidermal-dermal adherence in human skin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (23): 14516–22. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.23.14516. PMID 9169408.

- ^ Salonen EM, Jauhiainen M, Zardi L, Vaheri A, Ehnholm C (December 1989). "Lipoprotein(a) binds to fibronectin and has serine proteinase activity capable of cleaving it". The EMBO Journal. 8 (13): 4035–40. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08586.x. PMC 401578. PMID 2531657.

- ^ Martin JA, Miller BA, Scherb MB, Lembke LA, Buckwalter JA (July 2002). "Co-localization of insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 and fibronectin in human articular cartilage". Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 10 (7): 556–63. doi:10.1053/joca.2002.0791. PMID 12127836.

- ^ Gui Y, Murphy LJ (May 2001). "Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) binds to fibronectin (FN): demonstration of IGF-I/IGFBP-3/fn ternary complexes in human plasma". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 86 (5): 2104–10. doi:10.1210/jcem.86.5.7472. PMID 11344214.

- ^ Chung CY, Zardi L, Erickson HP (December 1995). "Binding of tenascin-C to soluble fibronectin and matrix fibrils". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 270 (48): 29012–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.48.29012. PMID 7499434.

- ^ Zhou Y, Li L, Liu Q, Xing G, Kuai X, Sun J, et al. (May 2008). "E3 ubiquitin ligase SIAH1 mediates ubiquitination and degradation of TRB3". Cellular Signalling. 20 (5): 942–8. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.01.010. PMID 18276110.

Further reading

[edit]- ffrench-Constant C (December 1995). "Alternative splicing of fibronectin--many different proteins but few different functions". Experimental Cell Research. 221 (2): 261–71. doi:10.1006/excr.1995.1374. PMID 7493623.

- Snásel J, Pichová I (1997). "The cleavage of host cell proteins by HIV-1 protease". Folia Biologica. 42 (5): 227–30. doi:10.1007/BF02818986. PMID 8997639. S2CID 7617882.

- Schor SL, Schor AM (2003). "Phenotypic and genetic alterations in mammary stroma: implications for tumour progression". Breast Cancer Research. 3 (6): 373–9. doi:10.1186/bcr325. PMC 138703. PMID 11737888.

- Przybysz M, Katnik-Prastowska I (2002). "[Multifunction of fibronectin]" [Multifunction of fibronectin]. Postȩpy Higieny I Medycyny Doświadczalnej (in Polish). 55 (5): 699–713. PMID 11795204.

- Rameshwar P, Oh HS, Yook C, Gascon P, Chang VT (2003). "Substance p-fibronectin-cytokine interactions in myeloproliferative disorders with bone marrow fibrosis". Acta Haematologica. 109 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1159/000067268. PMID 12486316. S2CID 25830801.

- Cho J, Mosher DF (July 2006). "Role of fibronectin assembly in platelet thrombus formation". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 4 (7): 1461–9. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01943.x. PMID 16839338. S2CID 24109462.

- Schmidt DR, Kao WJ (January 2007). "The interrelated role of fibronectin and interleukin-1 in biomaterial-modulated macrophage function". Biomaterials. 28 (3): 371–82. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.08.041. PMID 16978691.

- Dallas SL, Chen Q, Sivakumar P (2006). "Dynamics of assembly and reorganization of extracellular matrix proteins". Current Topics in Developmental Biology. Vol. 75. pp. 1–24. doi:10.1016/S0070-2153(06)75001-3. ISBN 9780121531751. PMID 16984808.

External links

[edit]- Fibronectin, an Extracellular Adhesion Molecule

- The Fibronectin Protein

- Fibronectin at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Fibronectin molecular interactions

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P02751 (Human Fibronectin) at the PDBe-KB.

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P11276 (Mouse Fibronectin) at the PDBe-KB.