Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

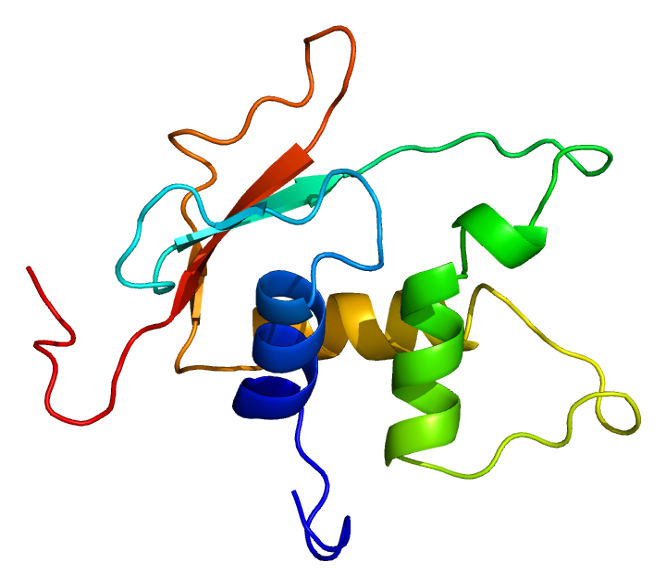

Interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) also known as MUM1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the IRF4 gene.[5][6][7] IRF4 functions as a key regulatory transcription factor in the development of human immune cells.[8][9] The expression of IRF4 is essential for the differentiation of T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes as well as certain myeloid cells.[8] Dysregulation of the IRF4 gene can result in IRF4 functioning either as an oncogene or a tumor-suppressor, depending on the context of the modification.[8]

The MUM1 symbol is also the current HGNC official symbol for melanoma associated antigen (mutated) 1 (HGNC:29641).

Immune cell development

[edit]IRF4 is a transcription factor belonging to the Interferon Regulatory Factor (IRF) family of transcription factors.[8][9] In contrast to some other IRF family members, IRF4 expression is not initiated by interferons; rather, IRF4 expression is promoted by a variety of bioactive stimuli, including antigen receptor engagement, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), IL-4, and CD40.[8][9] IRF4 can function either as an activating or an inhibitory transcription factor depending on its transcription cofactors.[8][9] IRF4 frequently cooperates with the cofactors B-cell lymphoma 6 protein (BCL6) and nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFATs).[8] IRF4 expression is limited to cells of the immune system, in particular T cells, B cells, macrophages and dendritic cells.[8][9]

T cell differentiation

[edit]IRF4 plays an important role in the regulation of T cell differentiation. In particular, IRF4 ensures the differentiation of CD4+ T helper cells into distinct subsets.[8] IRF4 is essential for the development of Th2 cells and Th17 cells. IRF4 regulates this differentiation via apoptosis and cytokine production, which can change depending on the stage of T cell development.[9] For example, IRF4 limits production of Th2-associated cytokines in naïve T cells while its upregulates the production of Th2 cytokines in effector and memory T cells.[8] While not essential, IRF4 is also believed to play a role in CD8+ cytotoxic T cell differentiation through its regulation of factors directly involved in this process, including BLIMP-1, BATF, T-bet, and RORγt.[8] IRF4 is necessary for effector function of T regulatory cells due to its role as a regulatory factor for BLIMP-1.[8]

B cell differentiation

[edit]IRF4 is an essential regulatory component at various stages of B cell development. In early B cell development, IRF4 functions alongside IRF8 to induce the expression of the Ikaros and Aiolos transcription factors, which decrease expression of the pre-B-cell-receptor.[9] IRF4 then regulates the secondary rearrangement of κ and λ chains, making IRF4 essential for the continued development of the BCR.[8]

IRF4 also occupies an essential position in the adaptive immune response of mature B cells. When IRF4 is absent, mature B cells fail to form germinal centers (GCs) and proliferate excessively in both the spleen and lymph nodes.[9] IRF4 expression commences GC formation through its upregulation of transcription factors BCL6 and POU2AF1, which promote germinal center formation.[10] IRF4 expression decreases in B cells once the germinal center forms, since IRF4 expression is not necessary for sustained GC function; however, IRF4 expression increases significantly when B cells prepare to leave the germinal center to form plasma cells.[9]

Long-lived plasma cells

[edit]Long-lived plasma cells are memory B cells that secrete high-affinity antibodies and help preserve immunological memory to specific antigens.[11] IRF4 plays a significant role at multiple stages of long-lived plasma cell differentiation. The effects of IRF4 expression are heavily dependent on the quantity of IRF4 present.[10] A limited presence of IRF4 activates BCL6, which is essential for the formation of germinal centers, from which plasma cells differentiate.[11] In contrast, elevated expression of IRF4 represses BCL6 expression and upregulates BLIMP-1 and Zbtb20 expression.[11] This response, dependent on a high dose of IRF4, helps initiate the differentiation of germinal center B cells into plasma cells.[11]

IRF4 expression is necessary for isotype class switch recombination in germinal center B cells that will become plasma cells. B cells that lack IRF4 fail to undergo immunoglobulin class switching.[9] Without IRF4, B cells fail to upregulate the AID enzyme, a component necessary for inducing mutations in immunoglobulin switch regions of B cell DNA during somatic hypermutation.[9] In the absence of IRF4, B cells will not differentiate into Ig-secreting plasma cells.[9]

IRF4 expression continues to be necessary for long-lived plasma cells once differentiation has occurred. In the absence of IRF4, long-lived plasma cells disappear, suggesting that IRF4 plays a role in regulating molecules essential for the continued survival of these cells.[11]

Myeloid cell differentiation

[edit]Among myeloid cells, IRF4 expression has been identified in dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages.[8][9]

Dendritic cells (DCs)

[edit]The transcription factors IRF4 and IRF8 work in concert to achieve DC differentiation.[8][9] IRF4 expression is responsible for inducing development of CD4+ DCs, while IRF8 expression is necessary for the development of CD8+ DCs.[9] Expression of either IRF4 or IRF8 can result in CD4-/CD8- DCs.[9] Differentiation of DC subtypes also depends on IRF4's interaction with the growth factor GM-CSF.[8] IRF4 expression is necessary for ensuring that monocyte-derived dendritic cells (Mo-DCs) can cross-present antigen to CD8+ cells.[8]

Macrophages

[edit]IRF4 and IRF8 are also significant transcription factors in the differentiation of common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) into macrophages.[8] IRF4 is expressed at a lower level than IRF8 in these progenitor cells; however, IRF4 expression appears to be particularly important for the development of M2 macrophages.[8] JMJD3, which regulates IRF4, has been identified as an important regulator of M2 macrophage polarization, suggesting that IRF4 may also take part in this regulatory process.[8]

Clinical significance

[edit]In melanocytic cells the IRF4 gene may be regulated by MITF.[12] IRF4 is a transcription factor that has been implicated in acute leukemia.[13] This gene is strongly associated with pigmentation: sensitivity of skin to sun exposure, freckles, blue eyes, and brown hair color.[14] A variant has been implicated in greying of hair.[15]

The World Health Organization (2016) provisionally defined "large B-cell lymphoma with IRF4 rearrangement" as a rare indolent large B-cell lymphoma of children and adolescents. This indolent lymphoma mimics, and must be distinguished from, pediatric-type follicular lymphoma.[16] The hallmark of large B-cell lymphoma with IRF4 rearrangement is the overexpression of the IRF4 gene by the disease's malignant cells. This overexpression is forced by the acquisition in these cells of a translocation of IRF4 from its site on the short (i.e. p) arm of chromosome 6 at position 25.3[17] to a site near the IGH@ immunoglobulin heavy locus on the long (i.e. q) arm of chromosome 14 at position 32.33[18][19]

Interactions

[edit]IRF4 has been shown to interact with:

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000137265 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000021356 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Grossman A, Mittrücker HW, Nicholl J, Suzuki A, Chung S, Antonio L, et al. (October 1996). "Cloning of human lymphocyte-specific interferon regulatory factor (hLSIRF/hIRF4) and mapping of the gene to 6p23-p25". Genomics. 37 (2): 229–233. doi:10.1006/geno.1996.0547. PMID 8921401. S2CID 42646350.

- ^ Xu D, Zhao L, Del Valle L, Miklossy J, Zhang L (July 2008). "Interferon regulatory factor 4 is involved in Epstein-Barr virus-mediated transformation of human B lymphocytes". Journal of Virology. 82 (13): 6251–6258. doi:10.1128/JVI.00163-08. PMC 2447047. PMID 18417578.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: IRF4 interferon regulatory factor 4".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Nam S, Lim J-S (2016). "Essential role of interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) in immune cell development." Arch. Pharm. Res. 39: 1548–1555. doi:10.1007/s12272-016-0854-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Shaffer AL, Tolga Emre NC, Romesser PB, Staudt LM (2009). "IRF4: Immunity. Malignancy! Therapy?" Clinical Cancer Research. 15 (9): 2954-2961. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1845

- ^ a b Laidlaw BJ, Cyster JG (2021). "Transcriptional regulation of memory B cell differentiation." Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21: 209–220. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-00446-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Khodadadi L, Cheng Q, Radbruch A and Hiepe F (2019). "The Maintenance of Memory Plasma Cells." Front. Immunol. 10: 721. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00721.

- ^ Hoek KS, Schlegel NC, Eichhoff OM, Widmer DS, Praetorius C, Einarsson SO, et al. (December 2008). "Novel MITF targets identified using a two-step DNA microarray strategy". Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research. 21 (6): 665–676. doi:10.1111/j.1755-148X.2008.00505.x. PMID 19067971. S2CID 24698373.

- ^ Adamaki M, Lambrou GI, Athanasiadou A, Tzanoudaki M, Vlahopoulos S, Moschovi M (2013). "Implication of IRF4 aberrant gene expression in the acute leukemias of childhood". PLOS ONE. 8 (8) e72326. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...872326A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0072326. PMC 3744475. PMID 23977280.

- ^ Praetorius C, Grill C, Stacey SN, Metcalf AM, Gorkin DU, Robinson KC, et al. (November 2013). "A polymorphism in IRF4 affects human pigmentation through a tyrosinase-dependent MITF/TFAP2A pathway". Cell. 155 (5): 1022–1033. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.022. PMC 3873608. PMID 24267888.

- ^ Adhikari K, Fontanil T, Cal S, Mendoza-Revilla J, Fuentes-Guajardo M, Chacón-Duque JC, et al. (March 2016). "A genome-wide association scan in admixed Latin Americans identifies loci influencing facial and scalp hair features". Nature Communications. 7 10815. Bibcode:2016NatCo...710815A. doi:10.1038/ncomms10815. PMC 4773514. PMID 26926045.

- "Grey hair gene discovered by scientists". BBC News. 1 March 2016.

- ^ Lynch RC, Gratzinger D, Advani RH (July 2017). "Clinical Impact of the 2016 Update to the WHO Lymphoma Classification". Current Treatment Options in Oncology. 18 (7) 45. doi:10.1007/s11864-017-0483-z. PMID 28670664. S2CID 4415738.

- ^ "IRF4 interferon regulatory factor 4 [Homo sapiens (Human)] - Gene - NCBI".

- ^ "IGH immunoglobulin heavy locus [Homo sapiens (Human)] - Gene - NCBI".

- ^ Woessmann W, Quintanilla-Martinez L (June 2019). "Rare mature B-cell lymphomas in children and adolescents". Hematological Oncology. 37 (Suppl 1): 53–61. doi:10.1002/hon.2585. PMID 31187530.

- ^ a b Gupta S, Jiang M, Anthony A, Pernis AB (December 1999). "Lineage-specific modulation of interleukin 4 signaling by interferon regulatory factor 4". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 190 (12): 1837–1848. doi:10.1084/jem.190.12.1837. PMC 2195723. PMID 10601358.

- ^ Rengarajan J, Mowen KA, McBride KD, Smith ED, Singh H, Glimcher LH (April 2002). "Interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) interacts with NFATc2 to modulate interleukin 4 gene expression". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 195 (8): 1003–1012. doi:10.1084/jem.20011128. PMC 2193700. PMID 11956291.

- ^ Brass AL, Zhu AQ, Singh H (February 1999). "Assembly requirements of PU.1-Pip (IRF-4) activator complexes: inhibiting function in vivo using fused dimers". The EMBO Journal. 18 (4): 977–991. doi:10.1093/emboj/18.4.977. PMC 1171190. PMID 10022840.

- ^ Escalante CR, Shen L, Escalante MC, Brass AL, Edwards TA, Singh H, Aggarwal AK (July 2002). "Crystallization and characterization of PU.1/IRF-4/DNA ternary complex". Journal of Structural Biology. 139 (1): 55–59. doi:10.1016/S1047-8477(02)00514-2. PMID 12372320.

Further reading

[edit]- Mamane Y, Sharma S, Grandvaux N, Hernandez E, Hiscott J (January 2002). "IRF-4 activities in HTLV-I-induced T cell leukemogenesis". Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research. 22 (1): 135–143. doi:10.1089/107999002753452746. PMID 11846984.

- Yamagata T, Nishida J, Tanaka S, Sakai R, Mitani K, Yoshida M, et al. (April 1996). "A novel interferon regulatory factor family transcription factor, ICSAT/Pip/LSIRF, that negatively regulates the activity of interferon-regulated genes". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 16 (4): 1283–1294. doi:10.1128/MCB.16.4.1283. PMC 231112. PMID 8657101.

- Iida S, Rao PH, Butler M, Corradini P, Boccadoro M, Klein B, et al. (October 1997). "Deregulation of MUM1/IRF4 by chromosomal translocation in multiple myeloma" (PDF). Nature Genetics. 17 (2): 226–230. doi:10.1038/ng1097-226. PMID 9326949. S2CID 30327940.

- Brass AL, Zhu AQ, Singh H (February 1999). "Assembly requirements of PU.1-Pip (IRF-4) activator complexes: inhibiting function in vivo using fused dimers". The EMBO Journal. 18 (4): 977–991. doi:10.1093/emboj/18.4.977. PMC 1171190. PMID 10022840.

- Rao S, Matsumura A, Yoon J, Simon MC (April 1999). "SPI-B activates transcription via a unique proline, serine, and threonine domain and exhibits DNA binding affinity differences from PU.1". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (16): 11115–11124. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.16.11115. PMID 10196196.

- Marecki S, Atchison ML, Fenton MJ (September 1999). "Differential expression and distinct functions of IFN regulatory factor 4 and IFN consensus sequence binding protein in macrophages". Journal of Immunology. 163 (5): 2713–2722. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.163.5.2713. PMID 10453013. S2CID 19537899.

- Gupta S, Jiang M, Anthony A, Pernis AB (December 1999). "Lineage-specific modulation of interleukin 4 signaling by interferon regulatory factor 4". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 190 (12): 1837–1848. doi:10.1084/jem.190.12.1837. PMC 2195723. PMID 10601358.

- Mamane Y, Sharma S, Petropoulos L, Lin R, Hiscott J (February 2000). "Posttranslational regulation of IRF-4 activity by the immunophilin FKBP52". Immunity. 12 (2): 129–140. doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80166-1. PMID 10714679.

- Gupta S, Anthony A, Pernis AB (May 2001). "Stage-specific modulation of IFN-regulatory factor 4 function by Krüppel-type zinc finger proteins". Journal of Immunology. 166 (10): 6104–6111. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.166.10.6104. PMID 11342629.

- Imaizumi Y, Kohno T, Yamada Y, Ikeda S, Tanaka Y, Tomonaga M, Matsuyama T (December 2001). "Possible involvement of interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) in a clinical subtype of adult T-cell leukemia". Japanese Journal of Cancer Research. 92 (12): 1284–1292. doi:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2001.tb02151.x. PMC 5926682. PMID 11749693.

- Rengarajan J, Mowen KA, McBride KD, Smith ED, Singh H, Glimcher LH (April 2002). "Interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) interacts with NFATc2 to modulate interleukin 4 gene expression". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 195 (8): 1003–1012. doi:10.1084/jem.20011128. PMC 2193700. PMID 11956291.

- Sharma S, Grandvaux N, Mamane Y, Genin P, Azimi N, Waldmann T, Hiscott J (September 2002). "Regulation of IFN regulatory factor 4 expression in human T cell leukemia virus-I-transformed T cells". Journal of Immunology. 169 (6): 3120–3130. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3120. PMID 12218129.

- Escalante CR, Shen L, Escalante MC, Brass AL, Edwards TA, Singh H, Aggarwal AK (July 2002). "Crystallization and characterization of PU.1/IRF-4/DNA ternary complex". Journal of Structural Biology. 139 (1): 55–59. doi:10.1016/S1047-8477(02)00514-2. PMID 12372320.

- Hu CM, Jang SY, Fanzo JC, Pernis AB (December 2002). "Modulation of T cell cytokine production by interferon regulatory factor-4". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (51): 49238–49246. doi:10.1074/jbc.M205895200. PMID 12374808.

- Fanzo JC, Hu CM, Jang SY, Pernis AB (February 2003). "Regulation of lymphocyte apoptosis by interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF-4)". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 197 (3): 303–314. doi:10.1084/jem.20020717. PMC 2193834. PMID 12566414.

- O'Reilly D, Quinn CM, El-Shanawany T, Gordon S, Greaves DR (June 2003). "Multiple Ets factors and interferon regulatory factor-4 modulate CD68 expression in a cell type-specific manner". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (24): 21909–21919. doi:10.1074/jbc.M212150200. PMID 12676954.

- Sundram U, Harvell JD, Rouse RV, Natkunam Y (August 2003). "Expression of the B-cell proliferation marker MUM1 by melanocytic lesions and comparison with S100, gp100 (HMB45), and MelanA". Modern Pathology. 16 (8): 802–810. doi:10.1097/01.MP.0000081726.49886.CF. PMID 12920225.

External links

[edit]- FactorBook IRF4

- IRF4+protein,+human at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.