Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Poseur

View on Wikipedia

A poseur is someone who poses for effect, or behaves affectedly,[1] who affects a particular attitude, character or manner to impress others,[2] or who pretends to belong to a particular group.[3][4] A poseur may be a person who pretends to be what they are not or an insincere person;[5] they may have a flair for drama or behave as if they are onstage in daily life.[6][7]

"Poseur" or "poseuse" is also used to mean a person who poses for a visual artist—a model.[8][9][10]

Examples

[edit]

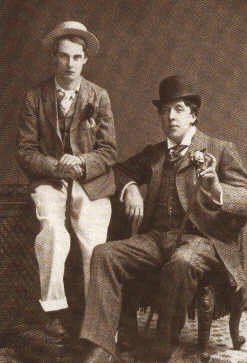

The playwright Oscar Wilde has been described as a "poseur".[11] Thomas Hardy said of him, "His early reputation as a poseur and fop – so necessary to his notoriety – recoiled upon the scholar and gentleman (as Wilde always innately was), and even upon the artist".[6]

Lord Alfred Douglas said of Wilde, "That he had what passed for genius nobody will, I think, nowadays dispute, though it used to be the fashion to pooh-pooh him for a mere poseur and decadent."[12]

The painter James A. Whistler has been sometimes described as a "poseur" for his manner and personal style.[13][14] It has been suggested that Whistler's genius lay partly in his ability to cultivate the role of the poseur, to "act as if he were always on stage", in order to stir interest, and cause people to wonder how such a poseur could create work that was so serious and authentic. His fame as an artist seemed to require that he present himself as a poseur.[15]

The playwright and critic, George Bernard Shaw, has been described as a poseur; in that context Shaw is quoted as saying, "I have never pretended that G.B.S. was real ... The whole point of the creature is that he is unique, fantastic, unrepresentative, inimitable, impossible, undesirable on any large scale, utterly unlike anybody that ever existed before, hopelessly unnatural, and void of real passion."[16]

In the ancient Greek comedy The Clouds, the playwright Aristophanes portrays Socrates as a "poseur".[17]

Etymology

[edit]The English term "poseur" is a loanword from French. The word in English use dates back to the mid 19th Century. It is from the French word poseur, and from the Old French word poser, meaning "to put, place, or set". The Online Etymology Dictionary, suggests that "poseur" is in fact the English word "poser" dressed "in French garb, and thus could itself be considered an affectation."[18]

Use within contemporary subcultures

[edit]"Poseur" is often a pejorative term, as used in the punk, heavy metal, hip hop, and goth subcultures, or the skateboarding, surfing and jazz communities, when it is used to refer to a person who copies the dress, speech, and/or mannerisms of a group or subculture, generally for attaining acceptability within the group or for popularity among various other groups, yet who is deemed not to share or understand the values or philosophy of the subculture.

Punk subculture

[edit]David Marsh, in an article in Rock & Rap, speaking of "those first punk kids in London" says, "The terms in which they expressed their disdain for hangers-on and those whose post-hip credentials didn't quite make it came straight out of the authenticity movements: Poseurs was the favorite epithet".[19] Ross Buncle argues that eventually the Australian punk scene "opened the door to a host of poseurs, who were less interested in the music than in UK-punk fancy dress and being seen to be hip".[20][unreliable source?] Describing a rehearsal of The Orphans, he says there "were no punk-identikit poseurs" present.[21] A 2015 article about early punk subculture in The New Republic states that punk "...was as immersive as a motorcycle gang or membership in the Mafia; part-time participants were derided as "poseurs", while any deviation from orthodoxy was a "sellout"...; this punk militancy created "... an economic and social ghetto which was nearly impenetrable to corporate infiltration and which only adventurous or deranged souls dared enter."[22]

In a review of The Clash film Rude Boy, a critic argued that this "film was another sign of how The Clash had sold out – a messy, vain work of punk poseurs".[23] US music journalist Lester Bangs praised punk pioneer Richard Hell for writing the "strongest, truest rock & roll I have heard in ages" without being an "arty poseur" of the "age of artifice".[24] Another critic argues that by the late 1970s, "punk rock had already, at this early date, shown signs of devolving into pure pose, black leather jacket and short hair required".[25] Please Kill Me includes interviews with punks in New York and Detroit who "rip their English counterparts as a bunch of sissified poseurs".[26]

The term poseur was used in several late-1970s punk songs, including the X-Ray Spex song "I Am a Poseur", which included the lyrics "I am a poseur and I don't care/I like to make people stare/Exhibition is the name." Another song using the term was the Television Personalities song "Part-Time Punks". The Television Personalities' song "was a reaction to the macho posturing of the English punk scene".[27] The lyrics argue that, "while Television Personalities were not themselves punks in the orthodox sense, neither was anyone else". The song "declared that either everyone who wanted to be a punk was one or that everyone was a poseur (or both)", and it argues that "the concept of [...] punk rock authenticity, of Joe Strummer, was a fiction".

An article in Drowned in Sound argues that 1980s-era "hardcore is the true spirit of punk" because "[a]fter all the poseurs and fashionistas fucked off to the next trend of skinny pink ties with New Romantic haircuts, singing wimpy lyrics". It argued that the hardcore scene consisted only of people "completely dedicated to the DIY ethics"; punk "[l]ifers without the ambition to one day settle into the study-work-family-house-retirement-death scenario".[28]

The Oi band Combat 84 has a song entitled "Poseur" which describes a person changing from a punk to a skinhead, and then into a Mod and a Ted. The lyrics include the lines "Poseur poseur standing there/You change your style every year."

In 1985, MTV aired a concert documentary, featuring performances by GBH and the Dickies, entitled Punks and Poseurs: A Journey Through the Los Angeles Underground.[29]

1990s–2000s

[edit]Dave Rimmer writes that with the revival of punk ideals of stripped-down music in the early 1990s, with grunge musicians like "[Kurt] Cobain, and lots of kids like him, rock & roll ... threw down a dare: Can you be pure enough, day after day, year after year, to prove your authenticity, to live up to the music [or else] live with being a poseur, a phony, a sellout?"[19]

Refused's Dennis Lyxzén and Bad Religion's Brett Gurewitz used the term to refer to early 2000s-era pop punk fans as "kids – more specifically the new wave of punk poseurs who came to the music via bands like Good Charlotte". They argue that these young listeners want "not to have to think and [instead they] would rather use music as escapism [,] and too many bands seem willing to comply".[30]

One writer argued that the Los Angeles punk scene was changed by the invasion of "antagonistic suburban poseurs", which bred "rising violence [...] and led to a general breakdown of the hardcore scene".[31] A writer for The Gauntlet praised the US Bombs' politically oriented albums as "a boulder of truth and authenticity in a sea of slick poseur sewage", and called them "real punk rockers" at "a time where the genre is littered with dumb songs about cars, girls and bong hits".[32]

Daniel S. Traber argues that attaining authenticity in the punk identity can be difficult; as the punk scene changed and re-invented itself, "[e]veryone got called a poseur".[33] One music writer argues that the punk scene produced "...true believers who spent long days fighting the man on streets of the big city [and living in squats who] always wanted to make punk rock less a cultural movement than some kind of meritocracy: "You have to prove you're good enough to listen to our music, man."[34]

Joe Keithley, the singer for D.O.A. said in an interview that: "For every person sporting an anarchy symbol without understanding it there’s an older punk who thinks they’re a poseur."[35] The interviewer, Liisa Ladouceur, argued that when a group or scene's "followers grow in number, the original devotees abandon it, [...] because it is now attracting too many poseurs—people the core group does not want to be associated with".[35]

The early 1980s hardcore punk band MDC penned a song entitled "Poseur Punk", which excoriated pretenders who copied the punk look without adopting its values. The lyrics sheet packaged with Magnus Dominus Corpus, the album on which "Poseur Punk" appears, contains a picture of the band Good Charlotte juxtaposed underneath the lyrics to "Poseur Punk". As part of MDC's 25th anniversary tour in the 2000s, frontman "Dictor's targets remain largely the same: warmongering politicians, money-grubbing punk poseurs (including Rancid, whose Tim Armstrong once worked as an M.D.C. roadie), and of course, cops".[36]

NOFX's album The War on Errorism includes the song "Decom-poseur", part of the album's overall "critique of punk rock's 21st century incarnation of itself". In an interview, NOFX's lead singer Mike Burkett (aka "Fat Mike") "lashes out" at "an entire population of bands he deems guilty of bastardizing a once socially feared and critically infallible genre" of punk, asking "[w]hen did punk rock become so safe?"[37]

Heavy metal subculture

[edit]Jeffrey Arnett argues that the heavy metal subculture classifies members into two categories: "acceptance as an authentic metalhead or rejection as a fake, a poseur".[38] In a 1993 profile of heavy metal fans' "subculture of alienation", the author notes that the scene classified some members as poseurs, that is, heavy metal performers or fans who pretended to be part of the subculture but who were deemed to lack authenticity and sincerity.[39] In 1986, SPIN magazine referred to "poseur metal".[40]

In 2014, Stewart Taylor wrote that in the Bay Area thrash metal scene in the 1980s, in venues where bands like Exodus played, metal fans who liked "hair metal" bands such as "Ratt, Mötley Crüe and Stryper" were considered to be poseurs.[41] A sociology book states that "[t]rue [metal] fans separate themselves from the posers through devotion to the history of the genre as well as the history of the particular bands and artists."[42] If a music fan came to an Exodus show at thrash clubs "...with a Motley Crue shirt or a Ratt shirt, Paul Baloff [of Exodus] would literally tear that shirt off the person's back," and then the band would "tear up the shirts and tie them around their wrists and wear them as trophies...[or]...badges of honor."[43] Additionally, "...Baloff would often command the audience to 'sacrifice a poseur'", a ritual that involved the audience throwing the suspected hair metal fan onto the stage.[43]

The Swedish black metal band Marduk, which aimed to be the "...most brutal and blasphemous band ever", uses Nazi imagery, such as the Nazi Panzer tank, in their songs and album art (e.g., their 1999 album is titled Panzer Division Marduk).[44] This use of Nazi imagery offended neo-Nazi black metal bands, who called Marduk poseurs.[44]

In the heavy metal subculture, some critics use the term to describe bands that are seen as excessively commercial, such as MTV-friendly glam metal groups in which hair, make-up, and fancy outfits are more important than the music.[citation needed] During the 1980s, thrash metal fans called pop metal bands "metal poseurs" or "false metal".[45] Another metal subgenre, nu metal is seen as controversial amongst fans of other metal genres, and the genres detractors have labeled nu metal derogatory terms such as "mallcore", "whinecore", "grunge for the zeros" and "sports-rock".[46]

Gregory Heaney of Allmusic has described the genre as "one of metal's more unfortunate pushes into the mainstream."[47] Jonathan Davis, the frontman of the pioneering nu metal band Korn, said in an interview:

There's a lot of closed-minded metal purists that would hate something because it's not true to metal or whatever, but Korn has never been a metal band, dude. We're not a metal band. We've always been looked at as what they called the nu-metal thing. But we've always been the black sheep and we never fitted into that kind of thing so … We're always ever-evolving, and we always piss fans off and we're gaining other fans and it is how it is.[48]

Ron Quintana wrote that when Metallica was trying to find a place in the LA metal scene in the early 1980s, it was difficult for the band to "play their [heavy] music and win over a crowd in a land where poseurs ruled and anything fast and heavy was ignored".[49]

David Rocher described Damian Montgomery, frontman of Ritual Carnage, as "an authentic, no-frills, poseur-bashing, nun-devouring kind of gentleman, an enthusiastic metalhead truly in love with the lifestyle he preaches... and unquestionably practises".[50] In 2002, Josh Wood argued that the "credibility of heavy metal" in North America is being destroyed by the genre's demotion to "horror movie soundtracks, wrestling events and, worst of all, the so-called 'Mall Core' groups like Slipknot and Korn", which makes the "true [metal] devotee's path to metaldom [...] perilous and fraught with poseurs."[51]

In an article on Axl Rose, entitled "Ex–'White-Boy Poseur'", Rose admitted that he has had "time to reflect on heavy-metal posturing" of the last few decades: "We thought we were so badass [...] Then N.W.A came out rapping about this world where you walk out of your house and you get shot. It was just so clear what stupid little white-boy poseurs we were."[52]

In the Alestorm song "Heavy Metal Pirates", numerous metaphors and allusions to pirates are made, including references to cutlasses, and it includes the line "No quarter for the poseurs, we'll bring 'em death and pain". The Manowar song "Metal Warriors" includes the lines: "Heavy metal or no metal at all whimps and posers leave the hall" and "...all whimps and posers go on, get out".

Goth subculture

[edit]Nancy Kilpatrick's Goth Bible: A Compendium for the Darkly Inclined defines "poseur" for the goth scene as: "goth wannabes, usually young kids going through a goth phase who do not hold to goth sensibilities but want to be part of the goth crowd...". Kilpatrick dismisses poseur goths as "Batbabies" whose clothing is bought at [mall store] Hot Topic with their parents' money.[53]

Hip hop subculture

[edit]

In the hip hop scene, authenticity or street cred is important. The word wigger is the specific used to refer to caucasian people mimicking black hip-hop culture. Larry Nager of The Cincinnati Enquirer wrote that rapper 50 Cent has "earned the right to use the trappings of gangsta rap – the macho posturing, the guns, the drugs, the big cars and magnums of champagne. He's not a poseur pretending to be a gangsta; he's the real thing."[54]

A This Are Music review of white rapper Rob Aston criticizes his "fake-gangsta posturing", calling him "a poseur faux-thug cross-bred with a junk punk" who glorifies "guns, bling, cars, bitches, and heroin" to the point that he seems like a parody.[55] A 2004 article on BlackAmericaWeb claims that Russell Tyrone Jones, better known as rapper Ol' Dirty Bastard, was not "a rough dude from the 'hood" as his official record company biographies claimed. After Jones' death from drugs, the rapper's father claimed that "his late son was a hip-hop poseur, contrary to what music trade magazines published in New York" wrote. Jones' father argued that the "story about him being raised in the Fort Greene [Brooklyn] projects on welfare until he was a child of 13 was a total lie"; instead, he said "their son grew up in a reasonably stable two-parent, two-income home in Brooklyn".

The article also refers to another "hip-hop poseur from a decade ago", Lichelle "Boss" Laws. While her record company promoted her as "the most gangsta of girl gangstas", posing her "with automatic weapons" and publicizing claims about prison time and an upbringing on the "hard-knock streets of Detroit", Laws' parents claim that they put her "through private school and enrolled [her] in college in suburban Detroit".[56]

As hip hop has gained a more mainstream popularity, it has spread to new audiences, including well-to-do "white hip-hop kids with gangsta aspirations—dubbed the 'Prep-School Gangsters'" by journalist Nancy Jo Sales. Sales claims that these hip hop fans "wore Polo and Hilfiger gear trendy among East Coast hip-hop acts" and rode downtown to black neighborhoods in chauffeured limos to experience the ghetto life. Then, "to guard against being labeled poseurs, the prep schoolers started to steal the gear that their parents could readily afford".[57] This trend was highlighted in The Offspring song "Pretty Fly (for a White Guy)".

A 2008, Utne Reader article describes the rise of "Hipster Rap", which "consists of the most recent crop of MCs and DJs who flout conventional hip-hop fashions, eschewing baggy clothes and gold chains for tight jeans, big sunglasses, the occasional keffiyeh, and other trappings of the hipster lifestyle". The article says this "hipster rap" has been criticized by the hip hop website Unkut and rapper Mazzi, who call the mainstream rappers poseurs or "fags for copping the metrosexual appearances of hipster fashion".[58] Prefix Mag writer Ethan Stanislawski argues that there "have been a slew of angry retorts to the rise of hipster rap", which he says can be summed up as "white kids want the funky otherness of hip-hop [...] without all the scary black people".[59]

African-American hip hop artist Azealia Banks has criticized Iggy Azalea, a white rapper, "for failing to comment on 'black issues', despite capitalising on the appropriation of African American culture in her music."[60] Banks has called her a "wigger," and there have been "accusations of racism" focused on her "insensitivity to the complexities of race relations and cultural appropriation."[60]

Other genres and subcultures

[edit]Mark Paytress writes that in 1977, Rolling Stones frontman Mick Jagger called singer/songwriter Patti Smith a "poseur of the worst kind, intellectual bullshit, trying to be a street girl".[61] A music writer for The Telegraph called Bob Dylan an "actor and a rock 'n' roll poseur to rival David Bowie and Mick Jagger at their most flamboyant".[62]

The skateboarding subculture attempts to differentiate between authentic skaters and pretenders. A New York Times article on the 2007 skateboarding scene notes that "some first-time skaters drawn into the sport by catchy choruses or candy-colored sneakers are dismissed as poseurs" who are "walking around with a skateboard as an accessory, holding it in a way we call 'the mall grab.'"[63] In the 1988 video game Skate or Die!, "Poseur Pete" is the name of the challenger for beginner-level players.

An LA City Beat magazine writer argues that "dance music had its Spinal Tap moment some time around the year 2000", arguing that "the prospect of fame, groupies, and easy money by playing other people's records on two turntables brought out the worst poseurs since hair metal ruled the Sunset Strip. Every dork with spiky locks and a mommy-bought record bag was a self-proclaimed turntable terror."[64] A Slate magazine article argues that while the independent music scene "can embrace some fascinating hermetic weirdos such as Joanna Newsom or Panda Bear, it's also prone to producing fine-arts-grad poseurs such as The Decemberists and poor-little-rich-boy-or-girl singer songwriters".[65]

In 1986, SPIN magazine referred to "poseur bikers", individuals who ride motorcycles and wear biker clothing, yet who lack the missing teeth and scars of real bikers.[40] An obituary for Colorado motorcycle enthusiast Walt Hankinson stated that "[h]e was an old-time biker, not a poseur", because he "...wasn’t looking for the most stylish leather outfit and never had a fashion crisis about what to wear on the next ride", instead just wearing a "flannel shirt, jeans and a cloth jacket" when he rode his motorcycle.[66]

In Canada, there are "alleged military posers", individuals who wear army uniforms and medals, who are not actually current or previous members of the armed forces. In November 2014, Ottawa police charged one of these alleged poseurs for impersonating a soldier, after he appeared in TV interviews during Remembrance Day ceremonies wearing a uniform and medals which he had no right to wear.[67]

The concept of a "jazz poseur" dates back to the 1940s. Bob White from Downbeat argued that some jazz critics knew nothing about new jazz (bebop) and nothing about chords, tone, or the technical aspects of jazz; instead, they would just learn the names of a few old masters and "...become a romantic, a charlatan, a poseur, a pseudo-intellectual, an aesthetic snob, ...well on the way to success" as a jazz critic.[68] In the 2000s, the CBC produced a radio show about how to spot "jazz poseurs" in a jazz scene. These were described as people who do not know much about the music, but they can "name-drop" the names of famous performers.[69]

Salon writer Joan Walsh calls US politician Paul Ryan a Randian poseur. She claims that while he purports to believe in Ayn Rand's Objectivist philosophy, which harshly criticizes government social redistribution programs, he actually benefitted from these programs in his life.[70]

Poseurs in the realm of sneakers and fashion have even been given their own name: "hypebeast". First coined in 2007 on forums like NikeTalk,[71] these people are said to "collect clothing, shoes, and accessories for the sole purpose of impressing others."[72] As opposed to the sneakerhead who purchases and collects shoes because he likes them, a hypebeast will only purchase a pair that is very popular among others and they gauge their self worth only on how many likes they can get on their #OOTD (outfit of the day) Instagram post with that coveted pair of sneakers on.[73]

Other meanings

[edit]In furnishing parlance, a "poseur table" is a high, small table, used by a standing person to place a drink or snacks on while they talk to other people. Poseur tables are used in bars, lounges, clubs and convention centres.[74] Poseur tables facilitate conversation and mingling at social events, because guests are not restricted by fixed seating and they can move about more freely.[74] Some poseur tables are used with high stools.

See also

[edit]Historical:

General:

References

[edit]- ^ Allen, R.E. Fowler, H. W. The Pocket Oxford Dictionary of Current English. Clarendon Press. (1984). ISBN 0198611331

- ^ Morris, William. editor. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. American Heritage Publishing. (1969) page 1022

- ^ "Cambridge Dictionaries Online". Dictionary.cambridge.org. Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ Definition of poseur Archived 26 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine at Dictionary.com

- ^ "poseur – Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". Merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 28 January 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ a b Hardy, Thomas. The Literary Notebooks of Thomas Hardy, Volume 2. Lennart A Björk, ed. Springer, 2016. ISBN 9781349066520. page 256.

- ^ Hicks, Wynford. Quite Literally: Problem Words and How to use Them. Routledge (2004) ISBN 9781134361656. page 174.

- ^ Waller, Susan. The Invention of the Model: Artists and Models in Paris, 1830-1870. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. (2006) ISBN 9780754634843. page 49-51

- ^ Burns, Sarah, Inventing the Modern Artist: Art and Culture in Gilded Age America. Yale University Press (1996) ISBN 9780300064452. p 183.

- ^ Madsen, Axel. Chanel: A Woman of Her Own. Macmillan (1991) ISBN 9780805016390. p 31

- ^ Ellis, Havelock, Mrs. "A Note on Oscar Wilde". The Lotus Magazine. Vol. 9, No. 4 (Jan., 1918), pp. 191-194. "When people say that Wilde was only a poser what do they mean? They forget that his 'poses' were his reality."

- ^ Douglas, Lord Alfred. Oscar Wilde and Myself. Duffield & Company. New York. (1914) Introduction. page 3.

- ^ Spielmann, Marion Harry. editor. "James A. McNeil Whistler, 1834—1903; Personal Recollections" The Magazine of Art, Volume 1. Cassell, Petter & Gallpin, 1903. page 578.

- ^ Alec-Tweedie, Mrs. Alec (Ethel). Thirteen Years of a Busy Woman's Life. Chapter XV. Publisher: John Lane (1912). page 168 - 175.

- ^ Burns, Sarah. Inventing the Modern Artist: Art and Culture in Gilded Age America. Yale University Press (1996) ISBN 9780300078596. p 236

- ^ Henderson, Archibald. George Bernard Shaw His Life and Works. Stewardt & Kidd Co. (1911). p 498

- ^ Silk, M.S. Aristophanes and the Definition of Comedy. Oxford University Press (2002) ISBN 9780199253821. p 172.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ a b Marsh, Dave (June 1995). "LIVE THROUGH THIS..." Rock & Rap Archives. 124. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ "The Orphans Story". Archived from the original on 2 October 2009.

- ^ "The Orphans - The Geeks & Other Perth Punk Stories". perthpunk.com. 8 July 2014. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016.

- ^ Svenonius, Ian (23 October 2015). "The Rise and Fall of College Rock: How yuppies and NPR gentrified punk". newrepublic.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Ranger, Joshua. "It Used to Be about the Music, Man: Rock 'n' Roll Fan Movies and the Post Facto Creation of the Nostalgia Market (archived MSWord document)". Archived from the original on 23 August 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ "Richard Hell Press Bio/Resumé". Richard Meyers & Roy Suggs. Archived from the original on 21 November 2000. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ "Genre Definitions". Starling.rinet.ru. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ Singer, Matthew. "Books that rock". Southland Publishing. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Leung, Godfre. "Towards a Post-Gendered Pop Music: Television Personalities' My Dark Places". Independent Culture. Archived from the original on 17 July 2006. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Symonds, Rene (16 August 2007). "Features – Soul Brothers: DiS meets Bad Brains". Drowned in Sound. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ "Vintage MTV: 'Punks and Poseurs: A Journey Through the Los Angeles Underground'". Dangerousminds.net. 21 August 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ "Exclaim! Music". Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ "Fantagraphics Books – Artist Bio – Los Bros. Hernandez". Fantagraphics.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Bombs – Heavy Metal – News – U.S. Bombs Videos – U.S. Bombs Ringtones – mp3s – Tabs – Wallpaper – lyrics". The Gauntlet. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ Traber, Daniel S. (2001). "L.A.'s 'White Minority': Punk and the Contradictions of Self-Marginalization". Cultural Critique. 48: 30–64. doi:10.1353/cul.2001.0040. S2CID 144067070.

- ^ Jacobson, Don (4 September 2007). "RockNotes: Punks vs. Poseurs". Beachwood Reporter. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ a b Ladouceur, Liisa (2004). "Lords of the New Church". This Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014.

- ^ Seigel, Stephen. "Soundbites | Soundbites". Tucson Weekly. Archived from the original on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ Dunning, Matt (29 June 2011). "Punk rock veterans come out swinging, flatten pop-punk". The Circle. Marist College. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012.

- ^ Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen. Metalheads: Heavy Metal Music and Adolescent Alienation (1996)

- ^ Arnett, Jeffrey (1993). "Three profiles of heavy metal fans: A taste for sensation and a subculture of alienation". Qualitative Sociology. 16 (4): 423–43. doi:10.1007/BF00989973. S2CID 143389132.

- ^ a b Gaines, Donna. "Biker Metal". Spin. Aug 1989. Vol. 5, No. 5 p. 27

- ^ Taylor, Stewart. Route A666 - A Heavy Metal Journey. Lulu Press, Inc, 2014. Second page of Ch. 5

- ^ Lundskow, George. The Sociology of Religion: A Substantive and Transdisciplinary Approach. Pine Forge Press, 2008. p. 377

- ^ a b Singh, Gary (7 December 2011). "Thrash Masters: A new book recalls the slam-dancing days in the mid-'80s when thrash metal bands stalked Bay Area stages at clubs like the Keystone Palo Alto and the New Varsity Theater". metroactive.com. Metroactive. Archived from the original on 4 June 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ a b Margasak, Peter (10 December 2009). "The List: December 10-16, 2009 Critics' Choices and other notable concerts: the Flaming Lips, Pelican, Keri Hilson, Marduk, Unsilent Night, and more". Chicagoreader.com. Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on 12 November 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ Berger, Harris M. and Greene Paul D. Metal Rules the Globe: Heavy Metal Music Around the World. Duke University Press, 2011. p. 39

- ^ Udo, Tommy (2002). Brave Nu World. Sanctuary Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 1-86074-415-X.

- ^ Heaney, Gregory. "Deftones - Koi No Yokan". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ^ "Korn's Jonathan Davis: 'We're Not A Metal Band'". Loud Wire. 17 February 2012. Archived from the original on 4 July 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ Quintana, Ron. "Metallica". artistwd.com / first published in Thrash Metal, US. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011.

- ^ Rocher, David. "The Great Eastern Trendkill". Chronicles of Chaos. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011.

- ^ Leonard, Christine. "FFWD Weekly, Nov 7, 2002". FFWD. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Yuan, Jada. "Ex–'White-Boy Poseur' - Axl Rose: Album delay is for the fans". New York Media Holdings LLC. Archived from the original on 23 April 2008. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Nancy Kilpatrick's Goth Bible: A Compendium for the Darkly Inclined 2004. page 24

- ^ Nager, Larry. "50 Cent's performance won't propel rapper to next level". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ "Diamonds and Lint, October 18th, 2007". This Are Music. Archived from the original on 23 February 2008.

- ^ Dawkins, Wayne. "Commentary: Middle-class rappers who extol thug life insult parents". BlackAmericaWeb.com, Inc. Archived from the original on 28 April 2005. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ "Peddling the Street: Gangsta Wannabes, Allen Iverson, and Black Masculinity (Under the Boards: The Cultural Revolution in Basketball, University of Nebraska Press/Bison Books, May 2007)". Archived from the original on 10 January 2010. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ Mohan, Jake. "Hipster Rap: The Latest Hater Battleground". Ogden Publications, Inc. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Stanislawski, Ethan. "The Chicago Reader has hip-hop hipster backlash against hip-hop hipster backlash". Prefix Mag', 20 June 2008. Archived from the original on 27 September 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ a b Monica Tan (5 December 2014). "Azealia Banks's Twitter beef with Iggy Azalea over US race issues misses point". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015.

- ^ Paytress, Mark (2003). The Rolling Stones: Off the Record. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0711988699. Archived from the original on 24 March 2013.

- ^ Hudson, Mark. "Bob Dylan: a poet and a poseur. There, I've said it..." Telegraph Media Group Limited 2009. Archived from the original on 29 May 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Detrick, Ben (11 November 2007). "Skateboarding Rolls Out of the Suburbs – New York Times". The New York Times. Brooklyn (NYC). Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ Romero, Dennis. "Poised Against Poseurs". LA CityBeat. Archived from the original on 8 March 2008. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Wilson, Carl. "The Trouble With Indie Rock". Washington Post.Newsweek Interactive Co. LLC. Archived from the original on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Culver, Virginia (8 April 2007). "Longtime biker reveled in the ride, taught others". The Denver Post. Archived from the original on 12 May 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ "Ottawa cops praised for charging alleged 'fake' soldier". Toronto Sun. 17 November 2014. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014.

- ^ The Rise of a Jazz Art World. Paul Douglas Lopes. Cambridge University Press, 30 May 2002 p. 202

- ^ "CBC Music". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ Paul Ryan: Randian poseur. Available online at: "Paul Ryan: Randian poseur". 12 August 2012. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2014.. Retrieved 5 March 2014

- ^ "How the Word "Hypebeast" Became So Popular". TheShoeGame.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ Anwar, Mehak (14 July 2015). "All Your Questios About Hypebeasts, Answered". bustle.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017.

- ^ "9 Signs You're Definitely A Hypebeast". narcity.com. 4 May 2016. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017.

- ^ a b "What is a poseur table". Onlinefurniturehire.com. Archived from the original on 13 September 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Andes, Linda (1998). "Growing Up Punk: Meaning and Commitment Careers in a Contemporary Youth Subculture". In Epstein, Jonathon S. (ed.). Youth Culture: Identity in a Postmodern World. Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers. pp. 212–31. ISBN 978-1-55786-851-0.

- Fox, K. J. (1987). "Real Punks and Pretenders: The Social Organization of a Counterculture". Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 16 (3): 344–70. doi:10.1177/0891241687163006. S2CID 145309467.

- Widdicombe, S.; Wooffitt, R. (1990). "'Being' Versus 'Doing' Punk: On Achieving Authenticity as a Member". Journal of Language and Social Psychology. 9 (4): 257–77. doi:10.1177/0261927X9094003. S2CID 145771710.

- Spitz, Marc. Poseur: A Memoir of Downtown New York City in the '90s. Da Capo Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0306821745