Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Prognathism

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2018) |

| Prognathism | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Habsburg jaw (in the case of mandibular prognathism) |

| |

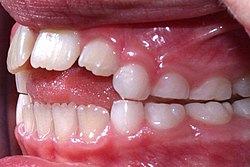

| Illustration of different types | |

| Specialty | Orthodontics |

| Types |

|

| Causes | Multifactorial |

| Treatment | Orthodontics; oral and maxillofacial surgery |

| Frequency |

|

Prognathism is a positional relationship of the mandible or maxilla to the skeletal base where either of the jaws protrudes beyond a predetermined imaginary line in the coronal plane of the skull.[clarification needed]

In the case of mandibular prognathism (never maxillary prognathism), this is often also referred to as Habsburg chin, Habsburg's chin, Habsburg jaw or Habsburg's jaw[2][3] especially when referenced with the context of its prevalence amongst historical members of the House of Habsburg.[2]

Mandibular prognathism is typically pathological, whereas maxillary prognathism is often the result of normal human population variation.

In general dentistry, oral and maxillofacial surgery, and orthodontics, this is assessed clinically or radiographically (cephalometrics). The word prognathism derives from the Greek πρό (pro, meaning 'forward') and γνάθος (gnáthos, 'jaw'). One or more types of prognathism can result in the common condition of malocclusion, in which an individual's top teeth and lower teeth do not align properly.[citation needed]

Presentation

[edit]

In humans, non-pathological maxillary and alveolar prognathism can occur due to normal variation among phenotypes.

However, mandibular prognathism is usually anomalous, and it may be a malformation, the result of injury, a disease state, or a hereditary condition.[4]

Prognathism is considered a disorder only if it affects chewing, speech or social function as a byproduct of severely affected aesthetics of the face.[citation needed]

Clinical determinants include soft tissue analysis where the clinician assesses nasolabial angle, the relationship of the soft tissue portion of the chin to the nose, and the relationship between the upper and lower lips; also used is dental arch relationship assessment such as Angle's classification.[citation needed]

Cephalometric analysis is the most accurate way of determining all types of prognathism, as it includes assessments of skeletal base, occlusal plane angulation, facial height, soft tissue assessment and anterior dental angulation. Various calculations and assessments of the information in a cephalometric radiograph allow the clinician to objectively determine dental and skeletal relationships and determine a treatment plan.[citation needed]

Prognathism should not be confused with micrognathism, although combinations of both are found.

Alveolar prognathism is a protrusion of that portion of the maxilla where the teeth are located, in the dental lining of the upper jaw.[citation needed]

Maxillary prognathism affects the middle third of the face, causing the maxilla to jut out, thereby increasing the facial area.

Mandibular prognathism is a protrusion of the mandible, affecting the lower third of the face.

Prognathism can also be used to describe ways that the maxillary and mandibular dental arches relate to one another, including malocclusion (where the upper and lower teeth do not align). When there is maxillary or alveolar prognathism which causes an alignment of the maxillary incisors significantly anterior to the lower teeth, the condition is called an overjet. When the reverse is the case, and the lower jaw extends forward beyond the upper, the condition is referred to as underbite (reverse overjet).[citation needed]

Classification

[edit]Alveolar prognathism

[edit]

Not all alveolar prognathism is anomalous, and significant differences can be observed among different ethnicities.[5]

Harmful habits such as thumb sucking or tongue thrusting can result in or exaggerate an alveolar prognathism, causing teeth to misalign.[6] Functional appliances can be used in growing children to help modify bad habits and neuro-muscular function, with the aim of correcting this condition.[6]

Alveolar prognathism can also easily be corrected with fixed orthodontic therapy. However, relapse is quite common, unless the cause is removed or a long-term retention is used.[7]

Maxillary prognathism

[edit]In disease states, maxillary prognathism is associated with Cornelia de Lange syndrome;[8] however, so-called false maxillary prognathism, or more accurately, retrognathism, where there is a lack of growth of the mandible, is by far a more common condition.[citation needed]

Prognathism, if not extremely severe, can be treated in growing patients with orthodontic functional or orthopaedic appliances. In adult patients this condition can be corrected by means of a combined surgical/orthodontic treatment, where most of the time a mandibular advancement is performed. The same can be said for mandibular prognathism.[citation needed]

On average, Neanderthals were far more prognathic than modern humans regarding the maxilla. This maxillary prognathism, along with their wide noses, suggests that their faces were not adapted to cold climate.[9]

Mandibular prognathism (progenism)

[edit]

Mandibular prognathism is a potentially disfiguring genetic disorder where the lower jaw outgrows the upper, resulting in an extended chin and a crossbite. In both humans and animals, it can be the result of inbreeding.[10]

Unlike alveolar or maxillary prognathism, which are common traits in some populations, mandibular prognathism is typically pathological. However, it is more common among East Asian populations but overall, the condition is polygenic.[11]

In brachycephalic or flat-faced dogs, like shih tzus and boxers, it can lead to problems such as underbite.[12]

In humans, it results in a condition sometimes called lantern jaw, reportedly derived from 15th century horn lanterns, which had convex sides.[13][a] Traits such as these were often exaggerated by inbreeding, and can be traced within specific families.[10]

Although more common than appreciated, the best known historical example is Habsburg jaw, or Habsburg or Austrian lip, due to its prevalence in members of the House of Habsburg, which can be traced in their portraits.[15] The process of portrait-mapping has provided tools for geneticists and pedigree analysis; most instances are considered polygenic,[16] but a number of researchers believe that this trait is transmitted through an autosomal recessive type of inheritance.[17][15]

Allegedly introduced into the family by a member of the Piast dynasty, it is clearly visible on family tomb sculptures in St. John's Cathedral, Warsaw. A high propensity for politically motivated intermarriage among Habsburgs meant the dynasty was virtually unparalleled in the degree of its inbreeding. Charles II of Spain, who lived 1661 to 1700, is said to have had the most pronounced case of the Habsburg jaw on record,[18] due to the high number of consanguineous marriages in the dynasty preceding his birth.[17][15]

Treatment of mandibular prognathism

[edit]Prior to the development of modern dentistry, there was no treatment for this condition; those who had it simply endured it. Today, the most common treatment for mandibular prognathism is a combination of orthodontics and orthognathic surgery. The orthodontics can involve braces, removal of teeth, or a mouthguard.[19]

In insects

[edit]In entomology, prognathous means that the mouthparts face forwards, being at the front of the head, rather than facing downwards as in some insects.[20]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wolff, Wienker & Sander 1993, p. 112.

- ^ a b Peacock, Zachary S.; Klein, Katherine P.; Mulliken, John B.; Kaban, Leonard B. (September 2014). "The Habsburg Jaw-re-examined". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 164A (9): 2263–2269. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.36639. PMID 24942320. S2CID 35651759.

- ^ Zamudio Martínez, Gabriela; Zamudio Martínez, Adriana (2020). "A Royal Family Heritage: The Habsburg Jaw". Facial Plastic Surgery & Aesthetic Medicine. 22 (2): 120–121. doi:10.1089/fpsam.2019.29017.mar. PMID 32083497. S2CID 211232475.

- ^ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Prognathism

- ^ Vioarsdóttir, O'Higgins & Stringer 2002, pp. 211–229.

- ^ a b Singh, Tenali Sushmitha; Sridevi, Enuganti; Sankar, Avula Jogendra Sai; Kakarla, Pranitha; Vallabaneni, Siva Sai Krishna; Sridhar, Mukthineni (2020). "Cephalometric Assessment of Dentoskeletal Characteristics in Children with Digit-sucking Habit". International Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry. 13 (3): 221–224. doi:10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1761. ISSN 0974-7052. PMC 7450188. PMID 32904107.

- ^ Sahil, Sahil; Soni, Sanjeev; Kaur, Gurpreet (2021-12-31). "Challenging Malocclusion in Orthodontics: the Open Bite". International Journal of Health Sciences: 125–134. doi:10.53730/ijhs.v5nS2.5581. ISSN 2550-6978.

- ^ "Medical Definition of de Lange syndrome". MedicineNet.

- ^ Rae, Todd C.; Koppe, Thomas; Stringer, Chris B. (27 October 2010). "The Neanderthal face is not cold adapted" (PDF). Moodle USP: e-Disciplinas. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ a b Vilas et al. 2019, pp. 563–571.

- ^ Kulkarni, Shilpa Devdatt; Bhad, Wasundhara A.; Doshi, Umal H. (2020). "Association Between Mandibular Prognathism and MATRILIN-1 Gene in Central India Population: A Cross-sectional Study". Journal of Indian Orthodontic Society. 55 (1): 28–32. doi:10.1177/0301574220956421.

- ^ Beuchat 2015.

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): PROGNATHISM, MANDIBULAR - 176700

- ^ "lantern jaw". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b c Vilas et al. 2019.

- ^ Wolff, Wienker & Sander 1993, pp. 112–116.

- ^ a b Безуглый, Т. А. (2020). "Влияние На Человека Признаков, Передаваемых По Аутосомно-Рецессивному Типу (на Примере Династии Габсбургов)" [Influence on the Human Traits Transmitted According to the Autosomal-Recessive Type (on the Example of the Habsburg Dynasty)] (in Russian).

- ^ Mitchell 2013, pp. 303–308.

- ^ "Treating Prognathism: Ways to Correct Abnormal Jaw Alignment".

- ^ "Prognathous". A Glossary of Entomological Terms. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

General and cited sources

[edit]- Beuchat, Carol (12 March 2015). "Why all the fuss about inbreeding?". Institute of Canine Biology. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Mitchell, Sylvia Z (May 2013). Mariana of Austria and Imperial Spain: Court, Dynastic, and International Politics in Seventeenth-Century Europe (Ph.D.). Coral Gables, Florida: University of Miami.

- Vilas, Román; Ceballos, Francisco C.; Al-Soufi, Laila; González-García, Raúl; Moreno, Carlos; Moreno, Manuel; Villanueva, Laura; Ruiz, Luis; Mateos, Jesús; González, David; Ruiz, Jennifer; Cinza, Aitor; Monje, Florencio; Álvarez, Gonzalo (17 November 2019). "Is the 'Habsburg jaw' related to inbreeding?". Annals of Human Biology. 46 (7–8): 553–561. doi:10.1080/03014460.2019.1687752. PMID 31786955. S2CID 208536371.

- Vioarsdóttir, US; O'Higgins, O; Stringer, C (2002). "A geometric morphometric study of regional differences in the ontogeny of the modern human facial skeleton". J. Anat. 201 (3): 211–229. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00092.x. PMC 1570912. PMID 12363273.

- Wolff, G; Wienker, T F; Sander, H (1 February 1993). "On the genetics of mandibular prognathism: analysis of large European noble families". Journal of Medical Genetics. 30 (2): 112–116. doi:10.1136/jmg.30.2.112. PMC 1016265. PMID 8445614.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of prognathism at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of prognathism at Wiktionary

Prognathism

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition

Prognathism refers to the abnormal forward protrusion of one or both jaws relative to the facial skeleton, often resulting in misalignment of the teeth and altered facial profile.[2] The term derives from the Greek words "pro" (forward) and "gnathos" (jaw), with "prognathous" first appearing in English in 1836 to describe protruding jaws, and "prognathism" entering usage by 1860 in anatomical literature.[5][6] Anatomically, prognathism can be distinguished as skeletal, involving the underlying bone structure of the maxilla (upper jaw) or mandible (lower jaw), or dental, pertaining to the position and alignment of the teeth within those bones.[1] Skeletal prognathism arises from disproportionate growth or positioning of the jaw bones relative to the cranial base, whereas dental prognathism results from discrepancies in tooth angulation or inclination without significant bony involvement.[7] Diagnosis typically relies on cephalometric measurements, such as the ANB angle, which assesses the anteroposterior relationship between the maxilla (point A) and mandible (point B) relative to the nasion (a point on the midline of the face). The normal range for the ANB angle is approximately 2–3 degrees; values less than 0 degrees indicate mandibular prognathism (Class III skeletal pattern), while greater deviations signal other discrepancies.[8] Additional metrics include the facial angle, formed by the intersection of the nasion-prosthion line and a reference line from the auditory meatus to the base of the nose, and the gnathic index, calculated as (basi-alveolar length × 100) / basal nasal length, where values exceeding 103 suggest prognathism.[9][10] These standards provide objective quantification of jaw protrusion beyond normal facial harmony. Prognathism manifests in types such as mandibular (lower jaw protrusion) or maxillary (upper jaw protrusion), each altering the occlusal relationship differently.[11]Epidemiology

Prognathism, particularly mandibular prognathism, exhibits significant variation in prevalence across global populations, estimated at 1-20% depending on the type and demographic group studied. In Caucasian populations, mandibular prognathism occurs in approximately 1% of individuals, while rates are substantially higher in Asian cohorts, reaching up to 15% overall and 8-40% in East Asian groups such as Chinese, Japanese, and Korean populations. African populations, including those from sub-Saharan regions, show prevalences of 10-16.8%, reflecting genetic and evolutionary skeletal adaptations.[3][12][13] These wide ranges may reflect differences in diagnostic criteria and severity thresholds across studies. Demographically, prognathism is more frequently diagnosed during adolescence, coinciding with pubertal growth spurts that accentuate skeletal discrepancies, though it can manifest across all ages. A slight male predominance is observed, particularly in mandibular cases, where males exhibit larger mandibular dimensions and higher rates of severe Class III malocclusion compared to females. This gender difference may relate to hormonal influences on craniofacial growth, with studies noting greater linear measurements in affected males.[14] Regional variations highlight ethnic and geographic influences, with higher incidences in populations exhibiting historical skeletal adaptations. For instance, Indigenous Australian groups demonstrate increased facial prognathism, characterized by greater gnathic indices compared to other populations, potentially linked to ancestral dietary and environmental factors. In contrast, lower rates prevail in European-derived groups, underscoring polygenic and population-specific patterns. These disparities are associated with genetic factors, as explored in etiology studies.[15] Over time, orthodontic data from post-2000 studies indicate variable prevalences in prognathism, potentially influenced by improved detection methods.[16][17]Clinical Presentation

Symptoms

Prognathism manifests through several visible signs that alter the facial profile. The most prominent feature is the forward protrusion of the jaw, either the mandible (lower jaw) in mandibular prognathism or the maxilla (upper jaw) in maxillary prognathism. In mandibular prognathism, this often results in a Class III malocclusion where the lower teeth overlap the upper teeth, leading to an underbite appearance, lip incompetence where the lips do not fully close at rest, and an overall concave or "dish-faced" profile in severe cases. In maxillary prognathism, it typically results in a Class II malocclusion with increased overjet.[1][2] Functional symptoms commonly arise from the misalignment, including difficulties in chewing and biting due to improper occlusion, which may cause uneven tooth wear or discomfort during mastication. Speech impediments, such as lisping or slurred articulation of sibilant sounds, occur because of altered tongue positioning relative to the teeth. Patients may also experience temporomandibular joint (TMJ) issues, including pain, clicking, or popping sensations during jaw movement, with studies reporting TMJ symptoms in 24% to 46% of individuals with mandibular prognathism.[1][18][19] Aesthetic concerns significantly impact quality of life, as the altered facial harmony can lead to self-esteem issues and social anxiety, particularly in adolescents and young adults. Research indicates that individuals with mandibular prognathism often report lower self-confidence, avoidance of smiling in public, and dissatisfaction with their facial profile compared to the general population.[1][20] Symptoms may progress during puberty due to accelerated mandibular growth relative to the maxilla, exacerbating the protrusion and functional challenges in untreated cases. This differential growth pattern, observed in longitudinal studies, can intensify malocclusion and associated discomfort as skeletal maturity advances.[21][22]Associated Conditions

Prognathism is frequently associated with various dental complications arising from malocclusion, where the misalignment of the upper and lower teeth disrupts normal occlusion. This can lead to accelerated enamel wear due to uneven contact forces during chewing, increasing the risk of tooth sensitivity, fractures, and decay.[23] Additionally, malocclusion in prognathism contributes to periodontal disease by complicating oral hygiene and promoting plaque accumulation around misaligned teeth.[24] Impacted teeth may also occur, particularly in cases of severe protrusion, as adjacent teeth shift to compensate for the abnormal jaw alignment.[1] Systemically, prognathism appears in several genetic syndromes, notably Crouzon and Apert syndromes, both forms of craniosynostosis characterized by premature fusion of skull sutures. In Crouzon syndrome, relative mandibular prognathism often accompanies midface hypoplasia, leading to a distinctive facial profile.[25] Similarly, Apert syndrome features mandibular prognathism alongside syndactyly and other craniofacial anomalies.[26] Psychological comorbidities are common in individuals with prognathism, driven by aesthetic and functional concerns that affect self-esteem and social interactions. Research indicates higher prevalence of anxiety and depression among those with dentofacial deformities like prognathism compared to the general population.[1] These impacts are often exacerbated by chronic dissatisfaction with facial appearance, contributing to emotional distress.[27] Other associated conditions include temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders, which manifest as pain or clicking in the jaw, reported in 24-46% of cases involving mandibular prognathism due to uneven joint loading.[19]Etiology and Pathogenesis

Causes

Prognathism arises from a variety of etiological factors, broadly categorized by their origin into genetic, developmental, environmental, and iatrogenic causes. These factors contribute to imbalances in jaw growth and positioning, leading to protrusion of the maxilla, mandible, or both.Genetic Factors

Genetic influences play a primary role in many cases of prognathism, often following polygenic inheritance patterns where multiple genes interact to affect craniofacial development. Hereditary mandibular prognathism, for instance, is considered a polygenic trait resulting from the combined effects of various genetic and environmental elements.[28] Specific genes implicated in non-syndromic mandibular prognathism include MYO1H, MATN1, and ADAMTSL1.[3] In syndromic cases, specific mutations are implicated; for example, mutations in the FGFR2 gene are associated with Crouzon syndrome, which features premature fusion of skull sutures and relative mandibular prognathism due to maxillary hypoplasia.[29] Similarly, acrodysostosis, a rare genetic disorder, leads to disproportionate jaw growth with a prominent lower jaw relative to the underdeveloped upper jaw.[1] Other syndromes, such as Gorlin syndrome (basal cell nevus syndrome) and Down syndrome, also exhibit prognathism as part of abnormal facial bone development.[1][30]Developmental Influences

Developmental causes involve disruptions in the normal growth trajectories of the maxilla and mandible during childhood, often leading to unequal expansion of the jaws. Excess growth hormone, as seen in conditions like acromegaly or gigantism, promotes overgrowth of the mandible, resulting in prognathism; acromegaly specifically enlarges the lower jaw in adults due to pituitary tumors.[1][31] In children, congenital factors present at birth can predispose to jaw protrusion, with hormonal imbalances exacerbating disparities in maxillary versus mandibular growth.[1]Environmental Contributors

Environmental factors, particularly childhood habits and nutritional deficiencies, can alter jaw development and contribute to prognathism. Prolonged thumb-sucking or pacifier use beyond early childhood applies uneven pressure on the jaws, potentially leading to mandibular protrusion by influencing bone remodeling.[1] Mouth-breathing, often due to nasal obstruction, is associated with excessive mandibular growth and lowered tongue posture, promoting forward jaw positioning.[32] Nutritional deficiencies, such as vitamin D deficiency causing rickets, impair bone mineralization and can result in maxillary underdevelopment, leading to relative prognathism and malocclusion.Iatrogenic Causes

Iatrogenic causes stem from medical interventions or injuries that disrupt normal jaw alignment. Post-traumatic alterations, such as condylar fractures from blunt force trauma to the face, can cause growth disturbances in developing jaws, leading to prognathism through asymmetric remodeling or deviation.[1] Prior dental work or surgical procedures, including improper orthodontic treatment or orthognathic surgery complications, may induce unintended jaw protrusion by altering bone structure or healing processes.[33]Mechanisms

Prognathism arises from various pathophysiological mechanisms involving dysregulated growth, biomechanical influences, hormonal imbalances, and cellular signaling disruptions that alter jaw development and positioning. Growth dysregulation plays a central role in prognathism, particularly through differential ossification rates in cranial base sutures, which can lead to anterior displacement of the mandible relative to the maxilla. In conditions like craniofacial syndromes (e.g., Apert, Crouzon, and achondroplasia), mutations in genes such as FGFR2 and FGFR3 disrupt normal suture patency and ossification, resulting in shortened anterior cranial base lengths and midface hypoplasia that exaggerate mandibular prominence.[34] Specifically, reduced cranial base angles (e.g., SN/PP near 0°) and shorter S-N distances (e.g., 70.64 mm vs. 78.0 mm in controls) contribute to this forward mandibular shift by impairing balanced facial growth.[34] In mandibular prognathism, condylar hyperplasia further drives asymmetry via excessive unilateral condylar growth, characterized by accelerated and prolonged endochondral ossification with hypertrophic cartilage layers averaging 0.52 mm thick and increased osteoblast activity.[35] This process, often active during adolescence, results in greater bone volume on the affected side, progressive deviation, and occlusal changes, as evidenced by single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) uptake differences exceeding 10%.[35] Biomechanical factors, such as soft tissue pressures, influence bone remodeling in the jaws according to Wolff's law, which states that bone adapts its architecture to mechanical stresses by depositing or resorbing tissue accordingly.[36] For instance, tongue thrust or low tongue posture exerts abnormal forward pressure on the dentition and lingual cortices, promoting vertical alveolar growth in posterior regions and clockwise mandibular rotation that can manifest as mandibular prognathism.[37] This sustained pressure reduces upward supportive forces on the mandible, allowing posterior tooth extrusion and increased lower facial height, thereby altering jaw positioning through adaptive remodeling.[37] Hormonal influences, notably excess growth hormone (GH), contribute to prognathism via systemic overgrowth, as seen in acromegaly triggered by pituitary adenomas.[38] These adenomas, often somatotroph tumors with guanine nucleotide stimulatory protein gene mutations, cause autonomous GH secretion, elevating insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) levels that activate pathways like AKT to stimulate periosteal bone apposition and soft tissue hypertrophy.[38] In the craniofacial skeleton, this leads to mandibular enlargement, jaw protrusion, and thickening, with prognathism emerging as a hallmark due to disproportionate lower jaw growth post-epiphyseal closure.[38] At the cellular level, disruptions in bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathways underlie genetic forms of prognathism by impairing jaw morphogenesis. BMPs (e.g., BMP-2, BMP-4), expressed in facial ectoderm and neural crest-derived mesenchyme, regulate chondrogenesis and osteogenesis by upregulating Sox9 to promote mesenchymal proliferation and differentiation into chondrocytes.[39] Ectopic or sustained BMP signaling increases chondrocyte proliferation (e.g., 29% BrdU-positive cells vs. 15% in controls) and hypertrophy (via Col10 and Runx2 expression), leading to excessive cartilage formation and dysmorphic jaw elongation without proper endochondral ossification, contributing to prognathic phenotypes.[39] Conversely, BMP inhibition (e.g., via Noggin) truncates jaw elements, highlighting the pathway's dose-dependent role in balanced mandibular development.[39]Classification

Alveolar Prognathism

Alveolar prognathism is characterized by the forward protrusion of the alveolar processes—the portions of the maxilla and mandible that support the teeth—without substantial involvement of the underlying basal skeletal structures. This dentoalveolar condition often arises from factors such as dental crowding, proclination of the incisors, or habits that alter tooth positioning, leading to an increased labial inclination of the anterior teeth. It is typically quantified through clinical measurements like overjet, where an overjet exceeding 4 mm signifies notable protrusion of the upper incisors relative to the lower ones, distinguishing it from normal ranges of 2-3 mm.[40][41] This subtype commonly manifests as bimaxillary protrusion, involving both upper and lower dental arches, and is frequently observed in orthodontic cases classified as Angle Class II or III malocclusions due to the resultant misalignment. In populations seeking orthodontic care, alveolar prognathism in the form of bimaxillary protrusion shows a prevalence of approximately 10-20%, with higher rates reported in certain ethnic groups such as those of African or Asian descent, where it may affect up to 21% of adolescents.[42][43] Differentiation from skeletal prognathism relies on cephalometric analysis, where alveolar forms exhibit normal basal bone positioning, evidenced by SNA angles around 82° ± 2° (indicating maxillary position relative to the cranial base) and SNB angles around 80° ± 2° (for mandibular position), without deviations that would suggest underlying jaw discrepancies. In contrast, skeletal variants involve alterations in these angles or the overall facial skeleton.[40] Examples of alveolar prognathism often include cases influenced by prolonged childhood habits, such as extended pacifier use or thumb sucking, which can promote anterior tooth proclination and contribute to the condition, sometimes accompanied by secondary features like anterior open bite.[1]Bimaxillary Prognathism

Bimaxillary prognathism involves the skeletal protrusion of both the maxilla and mandible relative to the cranial base, resulting in a combined forward positioning of the upper and lower jaws. This condition is identified through cephalometric analysis showing elevated SNA (>82°) and SNB (>80°) angles, often leading to a convex facial profile and potential Class I or II malocclusion with excessive incisor protrusion.[40] Prevalence varies by population but is generally less common than isolated maxillary or mandibular forms, with higher occurrences in certain ethnic groups influenced by genetic factors. It may arise from multifactorial etiology including hereditary patterns and can complicate diagnosis due to the bilateral involvement. Differentiation from dentoalveolar bimaxillary protrusion requires assessment of basal bone positions versus alveolar compensations.[1]Maxillary Prognathism

Maxillary prognathism refers to the skeletal protrusion of the upper jaw, characterized by excessive anterior positioning of the maxilla relative to the cranial base. This condition is identified through cephalometric analysis, particularly when the SNA angle, which measures the relationship between sella, nasion, and point A on the maxilla, exceeds 82 degrees. Such positioning often leads to clinical manifestations including a gummy smile, marked by excessive gingival exposure during smiling, and contributes to Class II malocclusion, where the maxillary dentition is positioned anteriorly relative to the mandibular dentition. Maxillary prognathism is more prevalent in Caucasian populations compared to other ethnic groups, as Class II malocclusions are more common in these groups.[8][40][44] It has been associated with cleft palate repairs in select cases, where surgical interventions may influence maxillary growth patterns, potentially resulting in increased SNA angles due to factors like congenitally missing maxillary laterals.[45] Clinically, maxillary prognathism carries implications for both function and aesthetics, including potential risks of upper airway obstruction if combined with other craniofacial discrepancies, though the protrusion itself may sometimes enhance pharyngeal space. Aesthetically, it can produce a convex facial profile that compensates for underlying midface deficiencies, but often exacerbates concerns like lip incompetence or disproportionate facial harmony. Historically, early 20th-century orthognathic literature described this condition as maxillary hyperplasia, highlighting its recognition in the evolution of corrective surgical techniques.[46][47]Mandibular Prognathism

Mandibular prognathism refers to the abnormal forward protrusion of the mandible relative to the maxilla and cranial base, resulting in a Class III skeletal malocclusion where the lower jaw extends beyond the upper jaw. This condition arises from excessive mandibular growth or development, often manifesting as a convex facial profile with a prominent chin and altered occlusal relationships. In cephalometric evaluations, mandibular prognathism is characterized by an SNB angle exceeding 80 degrees, which measures the position of the mandibular pogonion relative to the sella-nasion line and indicates mandibular advancement.[48][49][50] The condition encompasses distinct subtypes: true prognathism, which is primarily skeletal and involves inherent overgrowth of the mandibular bone structure, and pseudoprognathism, which is postural or functional in origin, often due to forward mandibular positioning from habits, tongue thrust, or relative maxillary retrusion without true skeletal excess. True prognathism typically develops during growth phases and persists into adulthood, whereas pseudoprognathism may resolve with early intervention targeting the underlying posture. These subtypes are differentiated through clinical examination and imaging to guide appropriate management.[51][52] Prevalence of mandibular prognathism varies by ethnicity, with notably higher rates in Asian populations, estimated at 15% to 25%, compared to less than 1% in Caucasians; this disparity is attributed to genetic and environmental factors influencing craniofacial growth patterns. The condition is frequently associated with condylar hyperplasia, a pathologic overgrowth of the mandibular condyle that accelerates unilateral or bilateral mandibular elongation, often beginning in puberty and leading to progressive asymmetry or protrusion.[53][54][55][56] Clinically, mandibular prognathism contributes to functional challenges, such as anterior crossbite, where the lower anterior teeth occlude labial to the upper incisors, potentially causing masticatory inefficiency, speech impediments, and accelerated tooth wear. In anthropological contexts, the term "prognathism" (sometimes historically referred to as progenism) has been used to describe evolutionary adaptations in jaw profiles among human populations, highlighting variations in mandibular projection as a trait in fossil records and modern ethnic groups. Orthognathic surgery, such as mandibular setback, represents a key intervention for correcting severe skeletal discrepancies, though details are addressed in management discussions.[57][58][59]Diagnosis

History and Physical Examination

The diagnosis of prognathism begins with a thorough history taking to identify potential etiologies and assess the impact on the patient's quality of life. Clinicians inquire about family history, as prognathism can be hereditary, such as in cases of the Habsburg jaw, a form of mandibular prognathism linked to genetic inheritance.[1] Patients are questioned regarding the onset of symptoms, including difficulties with chewing, speech, breathing, or maintaining dental hygiene, which may indicate functional impairments associated with jaw protrusion.[1] Childhood habits, such as prolonged thumb-sucking or pacifier use, are evaluated, as these can contribute to alveolar or skeletal changes leading to prognathism.[1] Standardized questionnaires, like the Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need (IOTN), are often employed to quantify the severity of malocclusion and prioritize treatment based on dental health and esthetic components, with scores of 4 or 5 indicating a definite need for intervention in cases involving significant overjet or reverse overjet related to prognathism.[60] Physical examination focuses on clinical assessment of facial and intraoral structures to confirm the type and extent of prognathism without relying on imaging. Extraorally, the patient's facial profile is analyzed in natural head posture, observing for mandibular, maxillary, or bimaxillary protrusion that disrupts harmony.[1] A key technique involves evaluating lip position relative to the Ricketts E-line, an imaginary line from the tip of the nose to the soft tissue pogonion (chin), where normal upper and lower lips should lie approximately 4 mm and 2 mm behind the line, respectively; deviations, such as excessive lip protrusion, suggest prognathism affecting soft tissue esthetics.[61] Intraorally, inspection reveals malocclusions, including reverse overjet (e.g., greater than 3.5 mm) in mandibular prognathism or increased overjet (greater than 6 mm) in maxillary prognathism, alongside assessment of overbite and dental alignment to differentiate alveolar from skeletal components.[1][62] Dental impressions may also be taken to create study models for detailed evaluation of occlusion and dental relationships.[1] Palpation of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is performed bilaterally to detect tenderness, clicks, or deviations that may accompany prognathism due to altered occlusion.[63] Basic cephalometric screening during the physical exam involves soft tissue evaluation through direct measurement or visual approximation of facial proportions, such as the nasolabial angle or menton position, to gauge skeletal discrepancies without radiographic tools.[64] Red flags during examination include syndromic features, such as syndactyly (fusion of fingers or toes) suggestive of Apert syndrome, where relative mandibular prognathism arises from midface hypoplasia, prompting referral for genetic evaluation.[65] Other indicators, like coarse facial features in acromegaly, warrant multidisciplinary assessment to rule out underlying systemic conditions.[1]Imaging and Diagnostic Tools

Cephalometric radiography remains the cornerstone for diagnosing and quantifying prognathism through lateral cephalograms, which provide a two-dimensional assessment of craniofacial relationships. Standard analyses, such as those developed by Steiner and Downs, evaluate skeletal discrepancies by measuring key angles and linear dimensions relative to established norms for age, sex, and ethnicity. For instance, the ANB angle—formed by points A (subspinale), nasion, and B (supramentale)—typically ranges from 2 to 3 degrees in a balanced Class I skeletal pattern; values less than 0 degrees indicate mandibular prognathism due to relative mandibular advancement, while greater than 4 degrees suggest maxillary retrognathism or Class II patterns.[40] These norms facilitate the calculation of the ANB difference to confirm prognathic tendencies and guide orthodontic planning. Three-dimensional imaging, particularly cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), offers advanced volumetric assessment for precise quantification of prognathism, enabling multiplanar reconstructions and measurements of jaw volumes, asymmetries, and airway spaces. CBCT is especially valuable in complex cases where two-dimensional radiographs may underestimate skeletal variations, providing high-resolution images with isotropic voxels for accurate soft and hard tissue evaluation. The effective radiation dose for a typical CBCT scan of the maxillofacial region is approximately 50–100 μSv, significantly lower than conventional CT while maintaining diagnostic utility.[66][67] Panoramic X-rays complement these tools by visualizing dental involvement in prognathism, such as crowding, impactions, or root positions relative to the protruding jaws, in a single wide-field image of the dentition and surrounding bone. In cases with temporomandibular joint (TMJ) complications or soft tissue abnormalities, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is employed for detailed evaluation of disc position, joint effusion, and muscular dynamics without ionizing radiation.[68][69] For differential diagnosis, imaging modalities like CBCT and cephalometry help distinguish prognathism from retrognathism or facial asymmetry by quantifying anteroposterior discrepancies and bilateral skeletal differences; for example, mandibular prognathism shows increased condylar volume and forward positioning compared to retrognathism's posterior displacement.[70] These tools ensure accurate identification by integrating objective metrics with clinical findings from physical examination.Management

Conservative Treatments

Conservative treatments for prognathism primarily involve orthodontic interventions aimed at correcting dental and mild skeletal discrepancies without invasive procedures, particularly effective in growing patients or mild cases identified through classification such as alveolar or mild maxillary/mandibular forms.[71] These approaches leverage growth modification and dental camouflage to improve occlusion and aesthetics, often achieving success rates of 50-70% in mild prognathism where skeletal discrepancies are minimal.[49] Orthodontic interventions, such as braces or clear aligners, focus on aligning teeth and correcting the dental components of prognathism by retracting protruded incisors or adjusting arch relationships.[1] In adult patients, where growth modification is no longer possible, treatment emphasizes dental camouflage for maxillary prognathism, typically involving retraction of anterior teeth using braces or clear aligners, often combined with extraction of maxillary premolars and, in some cases, wisdom teeth to create space and reduce excessive overjet. In some online discussions, including on Reddit, cases of excessive upper jaw protrusion (e.g., 9 mm overjet) report recommendations from surgeons for orthodontic treatment with braces and such extractions, though jaw surgery communities frequently discuss orthognathic surgery as an alternative or necessary option for proper skeletal correction.[72][73][74] For maxillary prognathism, high-pull headgear applies forces to control excessive anterior maxillary growth, typically worn 12-14 hours daily with 400-500g per side, promoting vertical redirection and reducing protrusion.[75] In mandibular prognathism or associated Class III patterns, protraction headgear (facemask) advances the maxilla when deficiency contributes, yielding 2-3 mm forward movement in 9-12 months for mild cases.[71] Functional appliances are particularly useful in growing patients to redirect jaw growth non-invasively. Devices like the chin cup restrict excessive mandibular growth in prognathism by applying posterior and superior forces (400-500g, 10-14 hours/day), effectively increasing the SN-MP angle through clockwise mandibular rotation and retarding mandibular length over 1-2 years, though long-term skeletal effects are variable.[76] Similarly, the reverse twin block or Fränkel III appliance postures the mandible posteriorly while enhancing maxillary development, suitable for functional or mild skeletal Class III variants, with treatment durations of 6-12 months.[75] Temporary anchorage devices (TADs), such as miniscrews, can be used as adjuncts in orthodontic treatments to provide absolute anchorage for maxillary protraction or dental camouflage, improving efficacy in mild to moderate Class III cases, especially when combined with facemasks.[77] Behavioral modifications, including myofunctional therapy, address underlying habits like tongue thrusting or improper swallowing that exacerbate prognathism. This therapy involves targeted exercises to retrain orofacial muscles, typically spanning 6-24 months with daily sessions, improving tongue posture and reducing protrusive forces on the jaws.[78] Adjunctive measures, such as premolar extractions in cases of dental crowding, facilitate protrusion reduction by allowing anterior retraction, often combined with orthodontics for camouflage in mild mandibular prognathism.[79]Surgical Interventions

Surgical interventions for severe prognathism primarily involve orthognathic surgery to correct skeletal discrepancies that cannot be addressed through conservative means. These procedures aim to reposition the maxilla and/or mandible to achieve proper occlusion, facial harmony, and functional improvement. Indications typically include significant skeletal malocclusion with functional impairments such as masticatory difficulties or airway obstruction, confirmed through preoperative diagnosis.[80] For maxillary prognathism, the Le Fort I osteotomy is commonly performed to setback the maxilla, involving a horizontal cut above the teeth to allow posterior movement and fixation with plates and screws. This technique effectively reduces anterior projection while preserving dental structures. In mandibular prognathism, the bilateral sagittal split osteotomy (BSSO) is the standard procedure for mandibular reduction, splitting the ramus bilaterally to enable setback and rigid fixation, often resulting in stable outcomes. Combined bimaxillary procedures, integrating Le Fort I and BSSO, are frequently used for complex cases, with patient satisfaction rates exceeding 90% in long-term follow-up studies.[81][82][83] Adjunctive procedures such as genioplasty are often incorporated to refine chin position, either advancing or reducing it to balance the profile post-orthognathic correction. This sliding osteotomy of the mandible's anterior segment enhances aesthetic outcomes without altering the primary jaw repositioning. Surgical timing is generally post-adolescence, after skeletal growth cessation (typically ages 16-18 for females and 18-21 for males), to prevent relapse due to ongoing mandibular development.[84][85] Risks include neurosensory disturbances, with inferior alveolar nerve paresthesia occurring in 5-10% of cases persistently after BSSO, often manifesting as lower lip numbness. Other complications may involve infection, hematoma, or relapse, though modern rigid fixation minimizes these. Hospital stays typically last 1-3 days for monitoring, with initial recovery involving a soft diet and limited activity; full functional recovery, including return to normal diet and activities, takes 6-12 weeks, though complete bone healing may extend to 6 months.[86][87][88] Advances since the 2010s include computer-assisted surgical planning using 3D models derived from cone-beam computed tomography, enabling precise virtual simulations, custom guides, and improved accuracy in osteotomies. These tools reduce operative time and enhance predictability, particularly in complex prognathism cases.[89][90]Prognathism in Non-Humans

In Insects

In entomology, prognathism refers to a head orientation in which the long axis of the insect cranium is horizontal, positioning the mouthparts, including the mandibles, to project forward for effective biting and prey capture.[91] This contrasts with the hypognathous orientation, where the head is vertical and mouthparts are directed ventrally, as seen in many herbivorous or flying insects.[92] Prognathous heads are particularly adapted for predatory or burrowing lifestyles, allowing precise manipulation of food sources in confined spaces.[93] This morphology is prominent in predatory beetles, such as ground beetles (family Carabidae), where the forward-directed mandibles facilitate capturing and crushing prey like smaller arthropods.[94] Similarly, many ants (order Hymenoptera) exhibit prognathous heads, with the horizontal alignment continuing the axis of the body to enhance foraging efficiency in soil or litter environments.[95] The evolutionary advantage is evident in soil-dwelling species, where the forward projection aids in navigating tight burrows and accessing hidden resources, reducing the need for extensive head movement.[93] Anatomically, the prognathous head features an elongated cranium that accommodates the forward orientation, with the labrum (upper lip) and maxillae (paired appendages) aligned anteriorly to support the mandibles in a chewing mechanism.[96] The labrum forms a protective roof over the mouthparts, while the maxillae provide sensory and manipulative functions through their palps and laciniae.[97] Fossil evidence of biting mouthparts in early arthropods dates to the Devonian period, around 365 million years ago. Functionally, the prognathous configuration enhances feeding efficiency by optimizing bite force and leverage, as biomechanical models show it allows greater mechanical advantage during mandibular closure compared to other orientations.[91] This adaptation is distinct from skeletal protrusions in vertebrates, focusing instead on arthropod-specific mouthpart mechanics for resource acquisition in diverse habitats.[91]In Other Animals

Prognathism is a prominent feature in the evolutionary morphology of many non-human primates, particularly great apes such as gorillas, where it manifests as a significant anterior projection of the lower face relative to the upper face, facilitating enhanced muscle attachment sites for powerful mastication.[98] This trait is associated with covariation between facial block orientation and shape, including ventral rotation of the facial block that elongates the lower face vertically and narrows it superoinferiorly.[99] In fossil hominids, species like Australopithecus afarensis exhibit variable degrees of prognathism, with some mandibles showing gorilla-like robusticity that suggests adaptations for high bite forces and dietary processing of tough foods.[100] These evolutionary patterns highlight prognathism's role in linking cranial base flexion, facial elongation, and biomechanical efficiency across primate lineages.[101] In veterinary medicine, mandibular prognathism is common in brachycephalic dog breeds such as English Bulldogs and Pugs, where it typically presents as an underbite due to a shortened maxilla and relatively elongated mandible, leading to malocclusion, tooth crowding, and increased risk of dental disease.[102] This condition often exacerbates brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome by altering upper airway dynamics, though it is considered a breed standard despite welfare concerns.[103] Treatment options include orthodontic appliances, such as custom acrylic devices applied during developmental stages to reposition teeth and correct linguoversion of mandibular canines in small breeds, with successful outcomes reported in case studies involving extraoral fabrication for precise fit.[104] Surgical interventions, including orthognathic procedures or extractions, are employed for severe cases to alleviate functional impairments and prevent secondary complications like periodontal issues.[105] Among wildlife, the elongated rostrum in carnivores like wolves (Canis lupus) supports specialized jaw mechanics for prey capture and dismemberment, enhancing leverage for shearing and tearing actions during feeding.[106] This adaptation is evident in the craniofacial allometry of canids, where rostral morphology correlates with predatory ecology, differing from the more gracile forms in omnivorous mammals. In captive settings, such as zoos, pathological prognathism can arise from inbreeding, as seen in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) where captive individuals display more pronounced facial projection and asymmetry in the maxilla compared to wild counterparts, attributed to reduced genetic diversity and environmental factors.[107] Comparative anatomy reveals key differences in prognathism between non-human animals and humans, particularly in allometric scaling of the jaw relative to the cranium; in great apes, the splanchnocranium (visceral face) exhibits strong covariation with the endocranium (braincase), driving progressive elongation and prognathism through ontogeny as facial size increases steadily post-infancy.[108] This contrasts with human orthognathism, where reduced facial projection accompanies encephalization and minimal allometric influence on facial shape after early growth, underscoring divergent evolutionary trajectories in hominoids.[109] Such scaling patterns emphasize prognathism's adaptive plasticity across vertebrates, from mammalian predators to primates.References

- https://www.antwiki.org/wiki/Morphological_Terms