Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

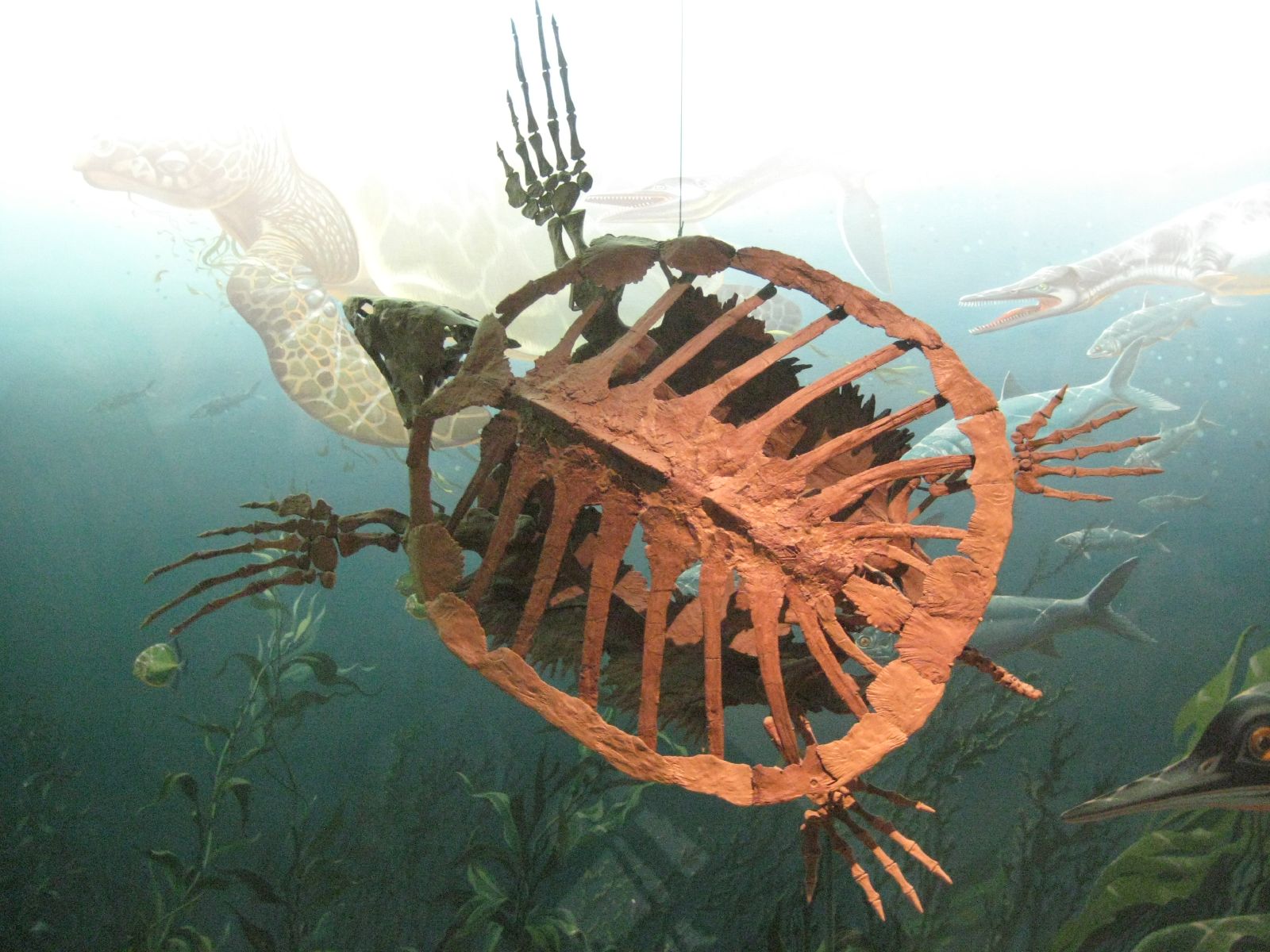

Protostega

View on WikipediaThis article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (May 2020) |

| Protostega Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Family: | †Protostegidae |

| Genus: | †Protostega Cope, 1872 |

| Type species | |

| †Protostega gigas Cope, 1872

| |

Protostega ('first roof')[1] is an extinct genus of sea turtle containing a single species, Protostega gigas. Its fossil remains have been found in the Smoky Hill Chalk formation of western Kansas (Hesperornis zone, dated to 83.5 million years ago[2]), time-equivalent beds of the Mooreville Chalk Formation of Alabama[3] and Campanian beds of the Rybushka Formation (Saratov Oblast, Russia).[4] Fossil specimens of this species were first collected in 1871, and named by Edward Drinker Cope in 1872.[5] With a total length of 3.9 metres (13 ft), it is the second-largest sea turtle that ever lived, second only to the giant Archelon,[6] and one of the three largest turtles of all time alongside Archelon and Gigantatypus.[7]

Discovery and history

[edit]The first known Protostega specimen (YPM 1408) was collected on July 4 by the 1871 Yale College Scientific Expedition, close to Fort Wallace and about 5 months before Cope arrived in Kansas. However, the fossil that they found was never described or named.[8] It was not named until 1872, when E. D. Cope found and collected the first identified specimen of Protostega gigas in the Kansas chalk in 1871. A variety of bones were found in yellow Cretaceous chalk from a bluff near Butte Creek.[9][10]

Paleoenvironment

[edit]The Late Cretaceous was marked by high temperatures, with large epicontinental seaways.[11] During the Mid-to-Late Cretaceous period the Western Interior Seaway covered the majority of North America and would connect to the Boreal and Tethyan oceans at times.[12][13] Within these regions are where the fossil of Protostega gigas have been found.[14][15]

Description

[edit]Protostega is known to have reached up to 3–3.9 m (9.8–12.8 ft) in length.[2][6][4] A specimen from the upper Taylor Marl is even larger, at 2 m (6.6 ft) in carapace length and 4.2 m (14 ft) in total length.[16][6] Despite lacking its head and three limbs, it is well-preserved.[16] Cope's Protostega gigas discovery revealed that their shell had a reduction of ossification that helped these huge animals with streamlining in the water and weight reduction.[17] The carapace was greatly reduced and the disk only extending less than halfway towards the distal ends of the ribs. Cope described other greatly modified bones in his specimen including an extremely long coracoid process that reached all the way to the pelvis and a humerus that resembled a Dermochelys,[18] creating better movement of their limbs.

Edward Cope described Protostega gigas as having a large jugal that reached to the quadrate along with a thickened pterygoid that reached to the mandibular articulating surface of the quadrate.[1] The fossil featured a reduction in the posterior portion of the vomer where the palatines meet medially.[1] Another fossilized specimen showed that a bony extension, that would have been viewed as a beak, was lacking in the Protostega genus.[8] The premaxillary beak was much shorter than that of Archelon.[18] In front of the orbital region the skull was elongated with a broadly-roofed temporal region. The jaws of the fossil showed a large crushing surface.[18] The quadrato-jugal was triangular with a posterior edge that was concave, with the entire bone being convex from distal view. The squamosal appeared to have a concave formation on the surface at the upper end of the quadrate. In Cope's fossil the mandible was preserved almost perfectly and from this he recorded that the jaw was very similar to the Cheloniidae and the dentary had a broad for above downward with a concave surface, marked by deep pits in the dentary.[19] Cope concluded that these animals were most likely omnivores and consumed a diet of hard shelled crustacean creatures, due to the long symphysis of its lower jaw.[18] Protostega also likely fed on seaweed and jellyfish or scavenged on floating carcasses as well, like modern turtles.[6]

Classification

[edit]The classification of Protostega was complicated at best. The specimen that Cope discovered in Kansas was hard to evaluate with the preservation condition. The fossil shared many characteristics with the genus Dermochelys and the family Cheloniidae. Cope wrote about the characteristics that distinctly separated this particular species from the two controversial groups. The differences he described were that the fossil had a reduced or lacking amount of dermal ossification on the back, the articulation of the pterygoid and quadrates, the presence of a presplenial bone in the jaw, a lack of an articular process on the back side of the nuchal, simple formation of the radial process on the humerus, and a peculiar bent formation of the xiphiplastra. He concluded that Protostega gigas was an intermediate form between Dermochelys and Cheloniidae.[19]

Paleobiology

[edit]Examining the bone tissue microstructure (osteohistology) of Protostega revealed growth patterns similar to modern leatherback sea turtles with rapid growth to large body size. Leatherbacks lack a typical reptile metabolism, instead having high resting metabolic rates and the ability to hold a body temperature higher than their surroundings. If Protostega had similar bone growth patterns to leatherbacks, it is hypothesized that they both had a similar metabolism. This rapid growth to adult body size in sea turtles would also indicate rapid growth to reproductive maturity, which would have been a great advantage in their survival. However, comparing Protostega to its more basal relative Desmatochelys shows that not all protostegids had the same growth patterns. This indicates that rapid growth to large size evolved late within the lineage, perhaps in response to the evolution of large mosasaurs like Tylosaurus. Given uncertainties in the phylogenetic placement of protostegids relative to living sea turtles, it is unclear if the evolution of rapid growth rates and possible elevated metabolism were convergent with modern leatherbacks or if the two were more closely related.[20]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Hirayama, Ren (1994). "Phylogenetic systematics of chelonioid sea turtles". Island Arc. 3 (4): 270–284. Bibcode:1994IsArc...3..270H. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1738.1994.tb00116.x. ISSN 1440-1738.

- ^ a b Carpenter, K. (2003). "Vertebrate Biostratigraphy of the Smoky Hill Chalk (Niobrara Formation) and the Sharon Springs Member (Pierre Shale)." High-Resolution Approaches in Stratigraphic Paleontology, 21: 421-437. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9053-0

- ^ Kiernan, Caitlin R. (2002). "Stratigraphic distribution and habitat segregation of mosasaurs in the Upper Cretaceous of western and central Alabama, with an historical review of Alabama mosasaur discoveries". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (1): 91–103. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0091:SDAHSO]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 130280406.

- ^ a b Danilov, I. G.; Obraztsova, E. M.; Arkhangelsky, M. S.; Ivanov, A. V.; Averianov, A. O. (2022). "Protostega gigas and other sea turtles from the Campanian of Eastern Europe, Russia" (PDF). Cretaceous Research. 135 105196. Bibcode:2022CrRes.13505196D. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2022.105196. S2CID 247431641. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-03-07.

- ^ Cope, Edward Drinker (1872). "A description of the genus Protostega". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia: 422–433.

- ^ a b c d Mike Everhart. "Marine turtles from the Western Interior Sea". OceansOfKansas.com. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022.

- ^ H. F. Kaddumi (2006). "A new genus and species of gigantic marine turtles (Chelonioidea: Cheloniidae) from the Maastrichtian of the Harrana Fauna-Jordan" (PDF). PalArch's Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology. 3 (1): 1–14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-24. Retrieved 2010-02-04.

- ^ a b "Protostega_dig-2011". oceansofkansas.com. Retrieved 2020-03-03.

- ^ Cope, Edward (1871). "A Description of the Genus Protostega, a Form of Extinct Testudinata". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 12 (86): 422–433.

- ^ Wiffen, J. (1981-03-01). "The first Late Cretaceous turtles from New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 24 (2): 293–299. Bibcode:1981NZJGG..24..293W. doi:10.1080/00288306.1981.10422718. ISSN 0028-8306.

- ^ Dennis, K. J.; Cochran, J. K.; Landman, N. H.; Schrag, D. P. (2013-01-15). "The climate of the Late Cretaceous: New insights from the application of the carbonate clumped isotope thermometer to Western Interior Seaway macrofossil". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 362: 51–65. Bibcode:2013E&PSL.362...51D. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2012.11.036. ISSN 0012-821X.

- ^ Schröder-Adams, Claudia J.; Cumbaa, Stephen L.; Bloch, John; Leckie, Dale A.; Craig, Jim; Seif El-Dein, Safaa A.; Simons, Dirk-Jan H. A. E.; Kenig, Fabien (2001-06-15). "Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian to Campanian) paleoenvironmental history of the Eastern Canadian margin of the Western Interior Seaway: bonebeds and anoxic events". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 170 (3): 261–289. Bibcode:2001PPP...170..261S. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(01)00259-0. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ Petersen, Sierra V.; Tabor, Clay R.; Lohmann, Kyger C.; Poulsen, Christopher J.; Meyer, Kyle W.; Carpenter, Scott J.; Erickson, J. Mark; Matsunaga, Kelly K. S.; Smith, Selena Y.; Sheldon, Nathan D. (2016-11-01). "Temperature and salinity of the Late Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway". Geology. 44 (11): 903–906. Bibcode:2016Geo....44..903P. doi:10.1130/G38311.1. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ^ "Mooreville Chalk", Wikipedia, 2019-12-16, retrieved 2020-03-04

- ^ Lutz, Peter L.; Musick, John A. (1996). The Biology of Sea Turtles. CRC Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-8493-8422-6.

- ^ a b Derstler, K.; Leitch, A. D.; Larson, P. L.; Finsley, C.; Hill, L. (1993). "The World's Largest Turtles - The Vienna Archelon (4.6 m) and the Dallas Protostega (4.2 m), Upper Cretaceous of South Dakota and Texas". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 13 (suppl. to no. 3) (33A).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Protostega gigas by Triebold Paleontology, Inc". trieboldpaleontology.com. Retrieved 2020-03-03.

- ^ a b c d Carnegie Institution of Washington (1908). Carnegie Institution of Washington publication. MBLWHOI Library. Washington, Carnegie Institution of Washington.

- ^ a b Case, Ermine Cowles (1897). On the Osteology and Relationships of Protostega. Ginn.

- ^ Wilson, Laura E. (2023). "Rapid growth in Late Cretaceous sea turtles reveals life history strategies similar to extant leatherbacks". PeerJ. 11 e14864. e14864. doi:10.7717/peerj.14864. PMC 9924133. PMID 36793890.

Protostega

View on GrokipediaDiscovery and Naming

Initial Discovery

The first known specimen of Protostega, a fragmentary fossil cataloged as YPM 1408, was collected on July 4, 1871, during a Yale College Scientific Expedition to western Kansas, led by paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh. This discovery occurred on the south side of the Smoky Hill River, approximately eight miles east of Fort Wallace, in exposures of the Smoky Hill Chalk Member of the Niobrara Chalk Formation. The Smoky Hill Chalk represents marine deposits from the Western Interior Seaway, a vast shallow sea that divided North America during the Late Cretaceous, facilitating rich preservation of marine vertebrates in fine-grained chalk sediments. These deposits played a pivotal role in early paleontological surveys of the American West, as expeditions like Marsh's targeted the Cretaceous outcrops for novel fossils amid the competitive "Bone Wars" era of discovery. The specific horizon yielding the Protostega specimen dates to the early Campanian stage, approximately 83.5 million years ago, within the Hesperornis biostratigraphic zone.[5] Due to its fragmentary condition—consisting of isolated bones that were not immediately diagnostic—the specimen was not formally recognized or described at the time of collection, highlighting possibilities for initial misidentification amid the era's focus on more complete marine reptile remains like mosasaurs. This oversight reflected the challenges of field paleontology in remote chalk badlands and the intense rivalry between Marsh and his contemporary Edward Drinker Cope, who later examined similar material. Cope formally named the genus Protostega in 1872 based on a more complete specimen he collected later that year from the same formation.Type Specimen and Subsequent Finds

The genus Protostega was formally named by Edward Drinker Cope in 1872, based on a partial skeleton (AMNH FR 1503) collected from the Smoky Hill Chalk Member of the Niobrara Formation in western Kansas, serving as the type specimen for P. gigas. This material, consisting primarily of plastron elements and limb bones, was described in Cope's publication in the Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. Subsequent discoveries expanded knowledge of Protostega gigas beyond the initial 1871 collection. In Kansas, paleontologist Charles H. Sternberg recovered multiple partial skeletons from the Smoky Hill Chalk during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including well-preserved carapaces and limbs now housed in institutions such as the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (e.g., CMNH 1420 and 1421).[6] These specimens contributed detailed insights into the turtle's skeletal variation and abundance in the Western Interior Seaway. Additional finds from Alabama include isolated bones and partial remains from the late Santonian to early Campanian Mooreville Chalk Formation (Selma Group) in the Black Belt region, indicating a southeastern extension of the species' range.[7] Further broadening the geographic distribution, isolated bones attributable to Protostega gigas were reported from the Campanian Rybushka Formation at the Beloe Ozero locality in Saratov Province, Russia, along the Upper Volga River, marking the first confirmed records outside North America and suggesting transatlantic dispersal capabilities.[8] Among these post-type discoveries, the largest known specimen of P. gigas, with an estimated total length of 4.2 meters, was collected from the Upper Cretaceous Taylor Group near Dallas, Texas, in the late 19th century and is now in the Perot Museum of Nature and Science.[9] This incomplete but substantial skeleton, lacking the head and some cervical vertebrae, has been pivotal in establishing upper limits for body size estimates in the genus, highlighting its position as one of the largest marine turtles.[9]Taxonomy and Classification

Etymology and Species

The genus name Protostega was coined by Edward Drinker Cope in 1871, combining the Greek roots "prōtos" (first) and "stegos" (roof or covering), in reference to the primitive, foundational structure of its carapace relative to later marine turtles. The species epithet "gigas" derives from the Latin word for "giant," highlighting the exceptional size of the type specimen, which measured over 3 meters in length. Protostega is currently regarded as monospecific, with P. gigas Cope, 1871 as the sole valid species; this consensus stems from comprehensive revisions that have synonymized all other proposed taxa under it. Historically, Oliver P. Hay proposed two additional species in 1908—P. potens and P. advena—based on partial skeletons from the Niobrara Formation in Kansas, distinguishing them primarily by plastron morphology and humerus proportions.[10] Rainer Zangerl further expanded the genus in 1953, recognizing P. potens and introducing P. dixie and P. latus as distinct species from the Selma Formation in Alabama and related deposits, citing variations in skull shape, fontanelle size, and carapace proportions. Post-2000 studies have invalidated these taxa, treating P. potens, P. advena, P. dixie, and P. latus as junior synonyms or ontogenetic/individual variants of P. gigas, often due to overlapping diagnostic features and insufficient differentiation in fragmentary material. This monospecific status was formalized by Hooks (1998) in a systematic review of Late Cretaceous turtles and reaffirmed in subsequent analyses, such as those incorporating European material.[11][12]Phylogenetic Relationships

Protostega is classified within the family Protostegidae, part of the superfamily Dermochelyoidea, and occupies an intermediate evolutionary position between the modern leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) and the hard-shelled sea turtles of the family Cheloniidae.[4] This placement reflects its role as a stem-group representative of Chelonioidea, basal to the crown groups Dermochelyidae and Cheloniidae, highlighting the diversification of marine turtles during the Late Cretaceous.[13] Phylogenetic analyses consistently recover Protostegidae as monophyletic, with Protostega gigas as the sole valid species within its genus, positioned outside the crown-group Chelonioidea.[14] Key synapomorphies supporting the phylogenetic position of Protostega include reduced dermal ossification in the carapace and plastron, an elongated temporal region in the skull, and highly modified paddle-like limbs adapted for marine propulsion.[14] These features align Protostegidae closely with Dermochelyidae in their loss of rigid shell plating but distinguish them from the more ossified Cheloniidae, suggesting convergent adaptations for open-ocean lifestyles.[4] Such traits underscore Protostega's transitional morphology in the evolution of chelonioid sea turtles. Cladistic analyses, such as those by Sterli et al. (2018), positioned Protostega as sister to Archelon within Protostegidae, based on expanded character matrices including cranial and postcranial features. More recent studies, including those incorporating osteohistological data, support this topology, with Protostega and Archelon forming a derived clade in Protostegidae and emphasizing stem Chelonioidea affinities.[4] These updates reinforce Protostegidae's exclusion from crown Chelonioidea, aligning fossil evidence with the K–T boundary radiation of modern sea turtle lineages.[13]Anatomy and Description

Size and General Morphology

Protostega gigas attained a substantial size for a marine turtle, with typical total body lengths of 2.7 to 3.4 meters based on complete and partial skeletons from the Late Cretaceous Smoky Hill Chalk Member. The largest known specimen (DMNH 1999) reached 3.4 meters, derived from scaling of limb bones such as the humerus and femur in the largest known individuals. Weight estimates, calculated through skeletal scaling and allometric regressions comparable to those used for modern sea turtles, fall between 400 and 900 kilograms, reflecting its robust yet buoyant build suited to oceanic environments.[1] The overall body plan of Protostega was highly streamlined, featuring a hydrodynamically efficient form with a dorsoventrally flattened profile that minimized drag during swimming. Its carapace and plastron exhibited reduced ossification compared to more rigid-shelled turtles, allowing greater flexibility and aiding in buoyancy control through adjustable body volume in water. This leathery, less mineralized shell structure parallels adaptations seen in the modern leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), though Protostega's was proportionally larger.[16][17] Limb proportions further emphasized its marine specialization, with elongated foreflippers that, when spread, spanned up to 4.7 meters in the largest specimens, providing powerful propulsion via paddling motions. These flippers, supported by elongated humeri and radii, were broader and more paddle-like than those of terrestrial turtles, enhancing maneuverability and speed in open water; individual foreflippers were approximately 1.5-1.6 times the length of the hind flippers. In comparison to extant sea turtles, Protostega was significantly larger than most species—such as the green turtle (Chelonia mydas), which reaches only about 1.5 meters—but smaller than its contemporary relative Archelon ischyros, which could reach up to 4.6 meters in total length.[18][19][20]Skeletal Features

The carapace of Protostega was characterized by a leathery texture, lacking the rigid ossification seen in many other turtles, and consisted of thin, elongated neural plates numbering 10 to 12 along the midline, which were often crested and covered the ribs only partially. These neural plates were paper-thin and prone to crushing in fossils, with the ribs remaining free for much of their distal length, contributing to a flexible dorsal shield. Peripheral plates were reduced in number and size, typically around 22 but variably developed, forming an incomplete bony margin that emphasized the overall lightweight construction of the shell.[21][22] The plastron consisted of 9 plates, comprising paired epiplastrons, hyoplastrons, hypoplastrons, and xiphiplastrons flanking a single entoplastron, with intricate digitations along the borders of the hyo- and hypoplastrons that enhanced flexibility compared to the more fused plastrons of hard-shelled taxa. This arrangement allowed for greater ventral mobility, as the plates were not fully co-ossified, and radial striations on elements like the hypoplastron indicate a structure suited to an active aquatic lifestyle.[23][8] The skull exhibited an elongated rostrum formed by distinct premaxillaries, maxillaries, and prefrontals, measuring approximately 58 cm in length when complete, with a narial opening about 7.5 cm long and 5.5 cm wide. Large temporal openings were defined by a prominent parieto-squamosal arch, providing space for robust jaw adductor musculature, while the overall cranial profile was narrow and elevated.[21][24] The vertebral column included 8 cervical vertebrae, 10 dorsal vertebrae with centra lengths increasing from 5.5 cm anteriorly to 9 cm mid-series, and an extended caudal series with chevron facets on the posterior centra facilitating articulation with hemal elements for tail-based propulsion in water. These facets, along with the short, wide cervical bodies, supported a streamlined axial skeleton.[21] The appendicular skeleton was adapted into broad paddles, with forelimbs spanning up to 250 cm when extended and hind limbs 190 cm, featuring hyperphalangy in the manus and pes where digits contained extra phalanges beyond the typical reptilian formula (e.g., front: 2-3-3-3-3, totaling 14 elements). The longest phalanges in the third manual digit reached 43 cm, enhancing paddle surface area akin to that in extant leatherback turtles.[21][25]Paleobiology

Growth and Physiology

Histological analysis of Protostega long bones, including humeri and femora, reveals a fibrolamellar bone microstructure characterized by high vascularization and spongiose tissue, indicative of rapid skeletal growth rates similar to those observed in modern leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea).[4] Lines of arrested growth (LAGs), interpreted as cyclical growth marks, are present in specimens, with counts up to eight LAGs suggesting individuals reached ages of approximately 8–9 years at death, during which humeral length doubled from about 18 cm to 35 cm.[4] This pattern of sustained, variable but fast deposition implies that Protostega potentially attained sexual and skeletal maturity within 10 years, enabling early reproduction in a high-energy marine lifestyle.[4] The absence of an external fundamental system (EFS) in the analyzed bones further supports that these individuals had not yet ceased growth, consistent with ongoing rapid ontogeny into adulthood.[4] Bone microstructure also points to an elevated metabolism in Protostega, with the highly vascularized tissue suggesting endothermic-like traits and gigantothermy, where large body size helped retain heat.[4] Such physiological strategies mirror those of leatherback turtles, which exhibit regional endothermy.[4]Diet and Behavior

Protostega gigas possessed a toothless but robust beak adapted for crushing, suggesting a primarily durophagous diet focused on hard-shelled mollusks such as inoceramid bivalves, with possible inclusion of softer prey like jellyfish, crustaceans, and seaweed based on anatomical comparisons to related protostegids.[26][27] Gut contents from a closely related Early Cretaceous protostegid (cf. Notochelone) containing fragments of inoceramid shells encased in phosphatic material confirm that such bivalves formed a regular part of the diet in the family, likely ingested after being bitten into segments along with associated soft tissues.[27] This feeding strategy aligns with the turtle's powerful jaws, enabling it to exploit benthic and pelagic resources in the Western Interior Seaway. Locomotion in Protostega was dominated by its enlarged foreflippers, which provided strong propulsive force for sustained open-ocean swimming, while the lightweight, flexible carapace—lacking extensive ossification—enhanced hydrodynamic efficiency and reduced drag.[28] The species likely undertook long-distance migrations across marine environments, similar to modern sea turtles, with the ability to haul itself onto coastal margins for nesting behaviors inferred from body plan and fossil trackway analogs in related taxa.[29] No direct evidence exists for coordinated group movements, supporting an inferred solitary lifestyle punctuated by periodic nesting events.[30] Fossil evidence reveals significant predation risks for Protostega, with multiple specimens exhibiting bite marks and embedded teeth from the large shark Cretoxyrhina mantelli, indicating lethal or scavenging interactions that often targeted the limbs and shell.[31] These injuries show no signs of healing in some cases, suggesting fatal attacks on live individuals, while possible encounters with mosasaurs are hypothesized from co-occurrence in the fossil record but lack specific bite trace confirmation for this genus.[29] The absence of gregarious fossils or trace evidence further implies that Protostega did not rely on social grouping for defense, relying instead on its size and speed for evasion.[32]Distribution and Paleoecology

Geographic Distribution

Protostega gigas fossils are primarily known from the Western Interior Seaway of North America, with abundant remains recovered from the Smoky Hill Chalk Member of the Niobrara Formation in western Kansas, USA.[1] The type specimen, described by Edward Drinker Cope in 1871, originates from Gove County, Kansas, within this formation. Additional material referred to Protostega sp. has been found in the Pierre Shale Formation, including the Pembina Member in southern Manitoba, Canada, and equivalents in South Dakota and New Mexico, USA, with protostegid remains reported from the latter. Secondary occurrences are documented in eastern North America, notably the Mooreville Chalk Formation (part of the Selma Group) in Greene County, Alabama, USA, where isolated bones and shark-bitten elements, including specimens with embedded teeth from the shark Cretoxyrhina mantelli, have been collected.[31] In Eurasia, the species is recorded from the Campanian Rybushka Formation at the Beloe Ozero locality in Saratov Province, Russia, marking the first confirmed finds outside North America based on isolated cranial and postcranial elements.[11] The temporal range of Protostega gigas is late Santonian to early Campanian stages of the Late Cretaceous, spanning approximately 86 to 80 million years ago, with the majority of specimens, including those from the Smoky Hill Chalk, dating to around 83.5 million years ago.[1] This distribution pattern, extending from the Western Interior Seaway across the Atlantic to the Tethyan margins in Europe, indicates trans-Atlantic dispersal facilitated by open marine connections via the Tethys Sea, supporting a cosmopolitan paleobiogeography for the species during the Santonian–Campanian.Habitat and Associated Fauna

Protostega inhabited the shallow to mid-depth waters of the Western Interior Seaway, an epicontinental sea that spanned central North America during the Late Cretaceous (late Santonian–early Campanian stages, approximately 86–80 million years ago). This environment featured depths up to ~200–500 meters overall, with the Niobrara Formation deposits indicating water depths of around 50–150 meters in the central basin.[33][34] Surface water temperatures averaged 30 ± 2.7 °C, reflecting a warm, tropical climate influenced by high global sea levels and greenhouse conditions, while bottom waters could be cooler and occasionally dysoxic due to oxygen fluctuations driven by upwelling and stratification.[35][36] The seaway's high productivity supported diverse marine life, with nutrient influx from surrounding landmasses promoting blooms of plankton and algae that formed the base of a complex food web.[37] Similar paleoenvironmental conditions extended to Tethyan marine settings, where comparable protostegid turtles thrived in warm, shallow epicontinental seas; for instance, Protostega gigas specimens from the Campanian Rybushka Formation in Saratov Province, Russia, suggest analogous habitats with tropical waters and high faunal diversity.[11] In the Western Interior Seaway, Protostega coexisted with a rich assemblage of marine vertebrates, including large predatory mosasaurs such as Tylosaurus proriger, short-necked plesiosaurs like Polycotylus, and giant teleost fish including Xiphactinus audax and various sharks.[1] Smaller cheloniids, such as Toxochelys species, also shared this habitat, occupying similar neritic zones.[38] As a mid-level consumer in this high-productivity ecosystem, Protostega likely foraged on abundant soft-bodied invertebrates and schooling fish, while serving as potential prey for apex predators like mosasaurs, evidenced by shark-bitten remains from Alabama and its rapid growth strategy to reach sizes up to 3.4 meters and reduce vulnerability.[1][31] Oxygen fluctuations, particularly during periods of anoxia in deeper basin areas, influenced preservation and distribution, with many Protostega fossils occurring in oxygen-poor chalk deposits of the Smoky Hill Chalk Member (Kansas) that reflect episodic dysoxia.[39] This dynamic paleoecology highlights the seaway as a vibrant, fluctuating marine realm supporting a balanced trophic structure amid global oceanic changes.[40]References

- https://www.[researchgate](/page/ResearchGate).net/publication/385756300_Shell_Constraints_on_Evolutionary_Body_Size-Limb_Size_Allometry_Can_Explain_Morphological_Conservatism_in_the_Turtle_Body_Plan