Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pseudomonadaceae

View on Wikipedia

| Pseudomonadaceae | |

|---|---|

| |

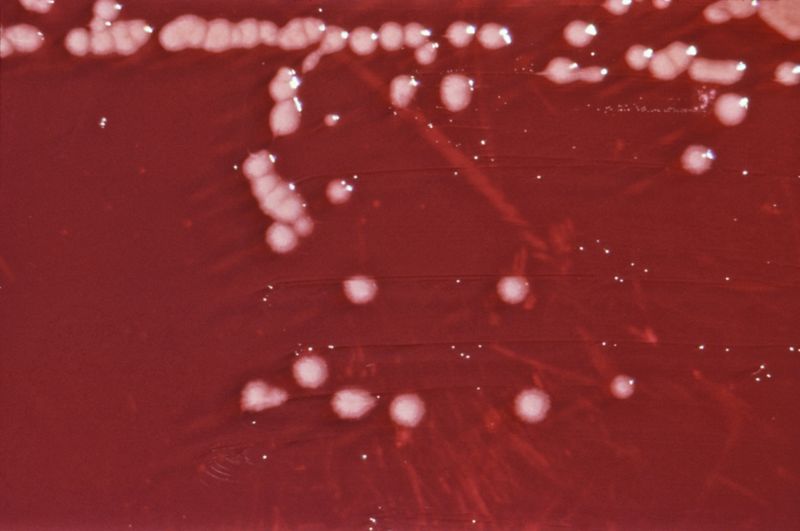

| P. aeruginosa colonies on an agar plate | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Kingdom: | Pseudomonadati |

| Phylum: | Pseudomonadota |

| Class: | Gammaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Pseudomonadales |

| Family: | Pseudomonadaceae Winslow et al., 1917 |

| Type genus | |

| Pseudomonas Migula 1894 (Approved Lists 1980)

| |

| Genera | |

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

The Pseudomonadaceae are a family of bacteria which includes the genera Azomonas, Azorhizophilus, Azotobacter, Mesophilobacter, Pseudomonas (the type genus), and Rugamonas.[2][3] The family Azotobacteraceae was recently reclassified into this family.[4]

History

[edit]Pseudomonad literally means false unit, being derived from the Greek pseudo (ψευδο- – false) and monas (μονος – a single unit). The term "monad" was used in the early history of microbiology to denote single-celled organisms. Because of their widespread occurrence in nature, the pseudomonads were observed early in the history of microbiology. The generic name Pseudomonas created for these organisms was defined in rather vague terms in 1894 as a genus of Gram-negative, rod-shaped, and polar-flagellated bacteria. Soon afterwards, a large number of species was assigned to the genus. Pseudomonads were isolated from many natural niches. New methodology and the inclusion of approaches based on the studies of conservative macromolecules have reclassified many species.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is increasingly recognized as an emerging opportunistic pathogen of clinical relevance. Studies also suggest the emergence of antibiotic resistance in P. aeruginosa.[5]

In 2000, the complete genome of a Pseudomonas species was sequenced; more recently, the genomes of other species have been sequenced, including P. aeruginosa PAO1 (2000), P. putida KT2440 (2002), P. fluorescens Pf-5 (2005), P. fluorescens PfO-1, and P. entomophila L48. Several pathovars of Pseudomonas syringae have been sequenced, including pathovar tomato DC3000 (2003), pathovar syringae B728a (2005), and pathovar phaseolica 1448A (2005).[3]

Distinguishing characteristics

[edit]- Oxidase positive – due to the presence of the enzyme cytochrome c oxidase.

- Nonfermentative

- Many metabolise glucose by the Entner-Doudoroff pathway mediated by 6-phosphoglyceraldehyde dehydrogenase and aldolase

- Polar flagella, enabling motility

- Many members produce derivatives of the fluorescent pigment pyoverdin[6]

The presence of oxidase and polar flagella and inability to carry out fermentation differentiate pseudomonads from the Enterobacteriaceae.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ Kennedy C, Rudnick P, MacDonald ML, Melton T (2015). "Azotobacter". Bergey's Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria. pp. 1–33. doi:10.1002/9781118960608.gbm01207. ISBN 9781118960608.

- ^ Skerman, McGowan; Sneath (1980). "Approved Lists of Bacterial Names". Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 30: 225–420. doi:10.1099/00207713-30-1-225.

- ^ a b Cornelis P (editor). (2008). Pseudomonas: Genomics and Molecular Biology (1st ed.). Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-19-6. [1].

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Rediers H, Vanderleyden J, De Mot R (2004). "Azotobacter vinelandii: a Pseudomonas in disguise?". Microbiology. 150 (Pt 5): 1117–9. doi:10.1099/mic.0.27096-0. PMID 15133068.

- ^ Carmeli, Y; Troillet, N; Eliopoulos, GM; Samore, MH (1999). "Emergence of Antibiotic-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Comparison of Risks Associated with Different Antipseudomonal Agents". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 43 (6): 1379–82. doi:10.1128/AAC.43.6.1379. PMC 89282. PMID 10348756.

- ^ Meyer J (2000). "Pyoverdines: pigments, siderophores and potential taxonomic markers of fluorescent Pseudomonas species". Arch Microbiol. 174 (3): 135–42. Bibcode:2000ArMic.174..135M. doi:10.1007/s002030000188. PMID 11041343. S2CID 13283224.

- ^ Krieg, N.R. (Ed.) (1984) Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Volume 1. Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-683-04108-8