Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pulled elbow

View on Wikipedia| Pulled elbow | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Radial head subluxation, annular ligament displacement,[1] nursemaid's elbow,[2] babysitter's elbow, subluxatio radii |

| |

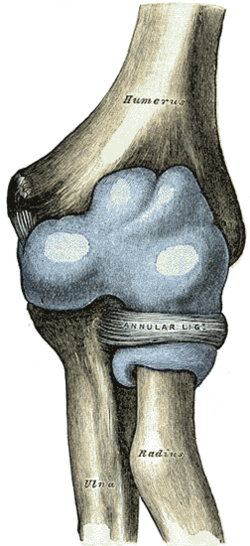

| Capsule of elbow-joint (distended). Anterior aspect. (Nursemaid's elbow involves the head of radius slipping out from the anular ligament of radius.) | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine |

| Symptoms | Unwilling to move the arm[2] |

| Usual onset | 1 to 4 years old[2] |

| Causes | Sudden pull on an extended arm[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, Xrays[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Elbow fracture[3] |

| Treatment | Reduction (forearm into a palms down position with straightening at the elbow)[1][2] |

| Prognosis | Recovery within minutes of reduction[1] |

| Frequency | Common[2] |

A pulled elbow, also known as nursemaid's elbow or a radial head subluxation,[4] is when the ligament that wraps around the radial head slips off.[1] Often a child will hold their arm against their body with the elbow slightly bent.[1] They will not move the arm as this results in pain.[2] Touching the arm, without moving the elbow, is usually not painful.[1]

A pulled elbow typically results from a sudden pull on an extended arm.[2] This may occur when lifting or swinging a child by the arms.[2] The underlying mechanism involves slippage of the annular ligament off of the head of the radius followed by the ligament getting stuck between the radius and humerus.[1] Diagnosis is often based on symptoms.[2] X-rays may be done to rule out other problems.[2]

Prevention is by avoiding potential causes.[2] Treatment is by reduction.[2] Moving the forearm into a palms down position with straightening at the elbow appears to be more effective than moving it into a palms up position followed by bending at the elbow.[1][4][5] Following a successful reduction the child should return to normal within a few minutes.[1] A pulled elbow is common.[2] It generally occurs in children between the ages of 1 and 4 years old, though it can happen up to 7 years old.[2]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Symptoms include:

- The child stops using the arm, which is held in extension (or slightly bent) and palm down.[6]

- Minimal swelling.

- All movements are permitted except supination.

- Caused by longitudinal traction with the wrist in pronation, although in a series only 51% of people were reported to have this mechanism, with 22% reporting falls, and patients less than 6 months of age noted to have the injury after rolling over in bed.[citation needed]

Cause

[edit]This injury has also been reported in babies younger than six months and in older children up to the preteen years. There is a slight predilection for this injury to occur in girls and in the left arm. The classic mechanism of injury is longitudinal traction on the arm with the wrist in pronation, as occurs when the child is lifted up by the wrist. There is no support for the common assumption that a relatively small head of the radius as compared to the neck of the radius predisposes the young to this injury.[citation needed]

Pathophysiology

[edit]The distal attachment of the annular ligament covering the radial head is weaker in children than in adults, allowing it to be more easily torn. The older child will usually point to the dorsal aspect of the proximal forearm when asked where it hurts. This may mislead one to suspect a buckle fracture of the proximal radius.[7] There is no tear in the soft tissue (probably due to the pliability of young connective tissues).[7]

The forearm contains two bones: the radius and the ulna. These bones are attached to each other both at the proximal, or elbow, end and also at the distal, or wrist, end. Among other movements, the forearm is capable of pronation and supination, which is to say rotation about the long axis of the forearm. In this movement the ulna, which is connected to the humerus by a simple hinge-joint, remains stationary, while the radius rotates, carrying the wrist and hand with it. To allow this rotation, the proximal (elbow) end of the radius is held in proximity to the ulna by a ligament known as the annular ligament. This is a circular ligamentous structure within which the radius is free, with constraints existing elsewhere in the forearm, to rotate. The proximal end of the radius in young children is conical, with the wider end of the cone nearest the elbow. With the passage of time the shape of this bone changes, becoming more cylindrical but with the proximal end being widened.[citation needed]

If the forearm of a young child is pulled, it is possible for this traction to pull the radius into the annular ligament with enough force to cause it to be jammed therein. This causes significant pain, partial limitation of flexion/extension of the elbow and total loss of pronation/supination in the affected arm. The situation is rare in adults, or in older children, because the changing shape of the radius associated with growth prevents it.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

[edit]Treatment

[edit]

To resolve the problem, the affected arm is moved in a way that causes the joint to move back into a normal position. The two main methods are hyperpronation and a combination of supination and flexion. Hyperpronation has a higher success rate and is less painful than a supination-flexion maneuver.[4][8]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Browner, EA (August 2013). "Nursemaid's Elbow (Annular Ligament Displacement)". Pediatrics in Review. 34 (8): 366–7, discussion 367. doi:10.1542/pir.34-8-366. PMID 23908364.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Nursemaid's Elbow". OrthoInfo - AAOS. February 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Cohen-Rosenblum, A; Bielski, RJ (1 June 2016). "Elbow Pain After a Fall: Nursemaid's Elbow or Fracture?". Pediatric Annals. 45 (6): e214–7. doi:10.3928/00904481-20160506-01. PMID 27294496.

- ^ a b c Krul, M; van der Wouden, JC; Kruithof, EJ; van Suijlekom-Smit, LW; Koes, BW (28 July 2017). "Manipulative interventions for reducing pulled elbow in young children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (7) CD007759. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007759.pub4. PMC 6483272. PMID 28753234.

- ^ Bexkens, R; Washburn, FJ; Eygendaal, D; van den Bekerom, MP; Oh, LS (January 2017). "Effectiveness of reduction maneuvers in the treatment of nursemaid's elbow: A systematic review and meta-analysis". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 35 (1): 159–163. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2016.10.059. PMID 27836316. S2CID 2315716.

- ^ Radial Head Subluxation Joint Reduction at eMedicine

- ^ a b Nursemaid Elbow at eMedicine

- ^ Bexkens, R; Washburn, FJ; Eygendaal, D; van den Bekerom, MP; Oh, LS (2 November 2016). "Effectiveness of reduction maneuvers in the treatment of nursemaid's elbow: A systematic review and meta-analysis". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 35 (1): 159–163. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2016.10.059. PMID 27836316. S2CID 2315716.