Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ramrod

View on Wikipedia

A ramrod (or scouring stick) is a metal or wooden device used with muzzleloading firearms to push the projectile up against the propellant (mainly blackpowder). The ramrod was used with weapons such as muskets and cannons and was usually held in a notch underneath the barrel.[1]

Use in firearms

[edit]Bullets that did not fit snugly in the barrel were often secured in place by a wad of paper or cloth, but either way, ramming was necessary to place the bullet securely at the rear of the barrel. Ramming was also needed to tamp the powder so that it would explode properly instead of fizzle (this was a leading cause of misfires).[1]

In some pistols from the 17th century, the ramrod is folded up in a small compartment at the end of the pommel.[2]

The ramrod could also be fitted with tools for various tasks such as cleaning the weapon, or retrieving a stuck bullet.[citation needed]

Caplock revolvers

[edit]Cap and ball revolvers were loaded a bit like muzzleloaders—powder was poured into each chamber of the cylinder from the muzzle end, and a bullet was then squeezed in. Such handguns usually had a ramming mechanism built into the frame. The user pulled a lever underneath the barrel of the pistol, which pushed a rammer into the aligned chamber.[citation needed]

Caplock revolvers mostly had mechanical devices with ramrods mounted on the frame of the revolver, which rammed the ball into the chamber of the cylinder by pulling a lever that was connected to the ramrod in various ways (by hinge, screw or lever). These mechanisms are called rammers or loading-levers. The most popular rammers used in caplock revolvers were the Colt, Adams and Kerr systems.

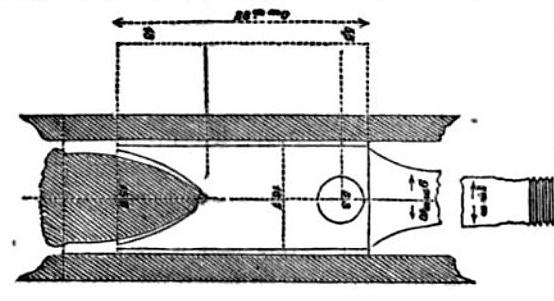

Colt's rammer

[edit]

Colt's rammer, patented by Samuel Colt about 1839, is a straight lever hinged under the barrel, with a triangular plate on its back end. The back corner of the triangle is hinged under the barrel, while the bottom corner is hinged to a short ramrod below and behind it. Pulling the lever down pushes the rod into the lowest chamber of the cylinder. This system was used on Colt revolvers from 1839 until 1873, when the Colt Peacemaker with metallic cartridges was introduced, as well as on Remington and Webley revolvers.[3][4]

Adams rammer

[edit]

Adams rammer, patented by Robert Adams in 1853, a straight or slightly downward-curving lever mounted on the left or right side of the frame with a screw at the front end and resting under the cylinder on the side of the stock when not in use. The lever pivots around a pin at the front end (on the frame of the revolver in front of and below the cylinder), and has a short ramrod in the middle, facing down in a fixed position. To use, the lever must be manually rotated down and forward for 270°, until the lever is in front of the cylinder and the rod enters one of the chambers, pressing the ball in. This mechanism was used on older Adams revolvers (on the left side of the revolver) and Webley Longspur revolvers (on the right side of the revolver).[5][6]

Kerr's rammer

[edit]

Kerr rammer, patented by James Kerr[7] in 1855,[5] a bent lever (bent downwards at a right or obtuse angle, with a short ramrod on the lower arm) which pivots about a pin on the front of the revolver frame in front of the cylinder and rests on the left side of the barrel when not in use. The lever must be turned up 90° to push the rod into the chamber. This mechanism was used in the Beaumont-Adams and Tranter revolvers, as well as the newer Adams and Webley Longspur revolvers.[8]

Artillery

[edit]Naval artillery began as muzzle-loading cannon and these too required ramming. Large muzzle loading guns continued into the 1880s, using wooden staffs worked by several sailors as ramrods.[9] Manual ramming was replaced with hydraulic powered ramming with trials on HMS Thunderer from 1874.[10]

Other uses

[edit]![]() The dictionary definition of Ramrod at Wiktionary indicates the term is also a used to describe a trail or ranch foreman, particularly one on cattle drives. It is also used as a verb to describe spurring or forcing a thing, such as a piece of legislation, forward. Similar to v. “spearhead”.

The dictionary definition of Ramrod at Wiktionary indicates the term is also a used to describe a trail or ranch foreman, particularly one on cattle drives. It is also used as a verb to describe spurring or forcing a thing, such as a piece of legislation, forward. Similar to v. “spearhead”.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Smith, Walter Harold Black; Ezell, Edward Clinton (1969). Small Arms of the World: The Basic Manual of Military Small Arms. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. p. 21. ISBN 9780811715669.

- ^ "Department of Arms and Armor Newsletter" (PDF). Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ Kinard, Jeff (2003). Pistols, An Illustrated History of Their Impact. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, Inc. p. 66. ISBN 1-85109-475-X.

- ^ Myatt, Major Frederick (1981). An Ilustrated Guide to Pistols and Revolvers. London: Salamander Books Limited. pp. 12, 30. ISBN 0861010973.

- ^ a b Zhuk, A.B. (1995). Walter, John (ed.). The illustrated encyclopedia of HANDGUNS, pistols and revolvers of the world, 1870 to 1995. Translated by Bobrov, N.N. London: Greenhill Books. p. 16. ISBN 1-85367-187-8.

- ^ Wilkinson, Frederick (1979). The Illustrated Book of Pistols. Optimum Books. pp. 122. ISBN 0600372049.

- ^ Kinard, Jeff (2003). Pistols, An Illustrated History of Their Impact. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, Inc. p. 77. ISBN 1-85109-475-X.

- ^ Wilkinson, Frederick (1979). The Illustrated Book of Pistols. Optimum Books. pp. 127. ISBN 0600372049.

- ^ Hodges, Peter (1981). The Big Gun: Battleship Main Armament 1860–1945. Conway Maritime Press. p. 10. ISBN 0-85177-144-0.

- ^ Hodges (1981), p. 19.

Literature

[edit]- Smith, Walter Harold Black; Ezell, Edward Clinton (1969). Small Arms of the World: The Basic Manual of Military Small Arms. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. p. 21. ISBN 9780811715669.

- Kinard, Jeff (2003). Pistols, An Illustrated History of Their Impact. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, Inc. p. 77. ISBN 1-85109-475-X.

- Zhuk, A.B. (1995). Walter, John (ed.). The illustrated encyclopedia of HANDGUNS, pistols and revolvers of the world, 1870 to 1995. Translated by Bobrov, N.N. London: Greenhill Books. p. 16. ISBN 1-85367-187-8.

- Wilkinson, Frederick (1979). The Illustrated Book of Pistols. Optimum Books. pp. 127. ISBN 0600372049.

- Myatt, Major Frederick (1981). An Illustrated Guide to Pistols and Revolvers. London: Salamander Books Limited. pp. 12, 30. ISBN 0861010973.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of ramrod at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of ramrod at Wiktionary