Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

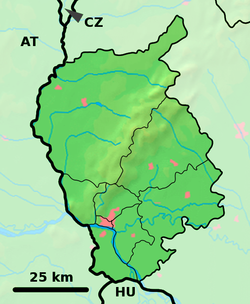

Reca (Hungarian: Réte) is a village and municipality in western Slovakia in Senec District in the Bratislava Region.

Key Information

Geography

[edit]The municipality lies at an altitude of 124 metres and covers an area of 9.921 km². It has a population of 1420 people.[4]

History

[edit]Pagan tomb-mounds excavated in an around Reca confirm the presence of Magyar mounted border guards from the 10th century.[citation needed]

In historical records the village was first mentioned in 1256, and was part of the dominion of Matthias Csák, the magnate of Trencsén. Documents confirm that before Csak, during the reign of the early Árpád kings, the settlement was inhabited by castle warriors (jobagiones castri) and controlled by the Count of Pozsony. The castle warriors of Reca developed into landowning lower nobility and Reca was a characteristic curial village of Pozsony County until the mid-20th century.[5][6]

During the Counter-Reformation in the 16th and 17th centuries, Reca (or Réthe, as it was then known) became the shelter of Bohemian and Moravian Protestants after the Battle of the White Mountain, because the Reca gentry was not subject to Catholic Habsburg religious laws. An estimated five-sixths of the Bohemian nobility went into exile soon after the Battle of White Mountain, and their properties were confiscated.[7] This period has left a Unity of the Brethren Chapel in the village, containing pieces of rare ecclesiastical plate. After the city of Skalica, Reca was one of the most significant locations in Royal Hungary for Czech exiles, with approximately 30 families settling there in the 17th century.[8]

In 1878 Reca briefly became known as Nemes Réte, in line with some other curial villages (e.g. Nemes Dedina. It also adopted a peculiar coat of arms consisting of the Royal arms of Hungary).[citation needed]

The 1892 Directory of Hungarian Merchants (which covers roughly 10-15% of the working populace of the Hungarian part of Austria-Hungary) lists the heads of families in Reca engaged in trade. It mainly covers Jewish families living in Reca as craftsmen and shopkeepers, and heads of gentry families engaged in horse-breeding which they subsequently sold in nearby Senec, Bratislava or Vienna.[9] The largest families in the list are the Doka (7 [and long-serving representatives of the noble commune of Reca]), Fadgyas (3), Karátsonyi (4), Klebercz (3), Pomichal (6) and Prikkel (3).[10]

During the First Vienna Award in 1938, Reca once more became part of Hungary, during the regime of admiral Miklós Horthy. In 1945 it was recovered by Czechoslovakia. A number of residents were affected by the Benes Decrees and tenthousands of Hungarian families were forced to move to Hungary and Czechia in 1947 as part of the colonisation of Slovaks in the region.[11]

Notable figures

[edit]The first individual known to documented history is Petrus Magnus de Réthe, a descendant of the original castle warriors, recorded in 1256 as a castle warrior of Bratislava Castle.[12]

A 1395 document records John and Peter of Reca as having been homini regi (or royal judges) during the reign of Louis I of Hungary (1326-1382).[13]

In 1485, another John of Reca is recorded as judge (iuidex nobilium) of Pozsony County.[14]

Nicholas of Reca was canon and vice-dean, and from 1489 to 1499 dean of the Chapter of Bratislava.[15]

Between 1504 and 1540, Andreas de Réthe was viscount (vice-comes) of Pozsony County (Bratislava).[16]

In the 17th century Péter Réthey was a familiaris (a Hungarian type of vassalage) of the Báthory family, whose members were Kings of Poland and Princes of Transylvania at the time. In 1620 he gained the manor of Füzérradvány from Elisabeth Báthory and her husband Ferenc Nádasdy. Péter Réthey constructed a large fortified seat which today remains one of the largest in Hungary.[17]

A notable 18th-century historical figure of Reca was György Réthey, a former Imperial cavalry officer who fought for Francis II Rákóczi, Prince of Transylvania and leader of the last major uprising of the Hungarian nobility against the Habsburg dynasty (see Rákóczi's War for Independence). Both György Réthey and his brother János defected from Imperial service and commanded hussar regiments under Rákóczi. In 1706, György Réthey led 3,000 men on an infamous attack on Styria, designed to plunder and pillage the local populace. 92 villages, two towns, and several castles were burned during the raid.[18] He also commanded his regiment at the Battle of Trencsén in 1708.

Ferenc Réthey, another eminent supporter of Rákóczi, was, amongst other activities, captain of the medieval Szécsény castle (which was destroyed after the uprising), captain of Sirok castle and, towards the end of his career, captain of Eger fortress and Heves County.[19] On 8 December 1710 Ferenc Réthey and Miklós Perényi capitulated Eger to the Habsburg field-marshal Count Johann Pálffy.[20] It is unclear how closely Ferenc Réthey was related to György Réthey, as prior to the 19th century members of Reca nobility often used only their predicate of "Réthey" or "de Réthe" (meaning 'of Reca') in correspondence and identification, and not their original family names which distinguish individual family lines.

László Dóka was főszolgabíró (Chief Constable) of Pozsony County from 1837 and deputy Judex Curiae Regi (the Lord Chief Justice of Hungary) in the first half of the 19th century, and Sándor Dóka was acting Governor of Pozsony County at the beginning of the 20th.[21]

Marián Réthei Prikkel (1871-1925), a cleric, compiled the first substantial collection of Hungarian folk dances.[22] He also published one of the first monographs on the important early medieval Hungarian manuscript, the Pray Codex.

Ferenc Réthey (1880-1952), a jurist and academic, was Count (Lord Lieutenant) of Moson County.[23]

Richárd Pomichal (1951-2010), was a well-known and popular Hungarian writer, teacher and biologist, who published widely on the ecology of the Csallóköz (Rye Island, Inselschutt) region, as well as writing on Hungarian history and the effects of the Trianon Treaty.[24][25]

István Pomichal (1965, Reca), an agriculturalist, is a member of parliament and the autonomous Bratislava region for the Party of the Hungarian Coalition, a party for the Hungarian minority in Slovakia[26] Pomichal's pedigree cattle, bred on an estate in Tomášov, has won a number of national and international gold prizes in Slovakia and Hungary.

Historical descriptions

[edit]Matthias Bel: The inhabitants are Hungarians, and not rustics: indeed, they are people both of noble birth and character (manners). They bread they eat is excellent and hospitality takes the first place there. They are proud of their ample herds and satisfied with the fruit of their farming. [27]

Vályi, András (1796): Hungarian village in Bratislava Castle County. Lord County Pálffy is the greatest landowner. The inhabitants are Catholics and Protestants, and the village is occupied by a number of nobles. It is half a mile from Puszta Födémes. The burghers of Bratislava send their young children to the village to learn the Hungarian language.[28]

Fényes, Elek (1851): Réthe, a populous Hungarian village in Bratislava Castle County, one hour east of Szencz. 491 Catholics, 49 Evangelical, 337 Reformed, 149 Jews. With a Reformed and Catholic church, and a synagogue. Large limits boundaries and beautiful expanse of fertile meadows, vast pastures, famous for sheep and cattle market. Many landowning nobles. One street leads to Cseklesz.[29]

Liszka, József (2003): The squires of Reca formed an individual group in the Matyusfold region. This social class of the village, which consisted of both Reformed and Catholics, was wealthier than the average. Their wealth was clear because their dwellings looked like manor houses, they employed liveried coachmen and they sent their children to schools in Bratislava from the 19th century. Reca noble families were also distinctive for their behaviour and mentality. "The necessary honourable elegance and a keeping of a certain distance" remained alive even after there was no longer any justification of property, i.e. in the second half of the 20th century.[30]

References in popular culture

[edit]Reca is the setting for the epic Hungarian film Rákóczi hadnagya (1954), or "Rákóczi's Lieutenant" in English. The heroic officer in the film, Lieutenant János Bornemissza, is driven by his "patriotism to Hungary and love for the beautiful Anna Bíró from Reca". When Reca falls into labanc hands Anna is imprisoned and only rescued by Bornemissza at the end of the film.[31][32]

References

[edit]- ^ "Hustota obyvateľstva - obce [om7014rr_ukaz: Rozloha (Štvorcový meter)]". www.statistics.sk (in Slovak). Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic. 31 March 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ a b c "Základná charakteristika". www.statistics.sk (in Slovak). Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic. 17 April 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "Počet obyvateľov podľa pohlavia - obce (ročne)". www.statistics.sk (in Slovak). Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic. 31 March 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "Population on 31st December 2012" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2013.

- ^ Liszka, József: Narodopis Madarov na Slovensku, Komarno - Dunajska Streda 2003

- ^ Korabinsky, Johann Matthias: Geographish-Historisches und Produkten Lexikon von Ungarn, Pressburg 1786: "Wird von Edelleuten bewohnt", p. 602

- ^ Battle of White Mountain

- ^ Zbirkova, Viera: Reca: Ceski bratia v Reci koncom 17. a na zaciatku 18. storocia (Bratislava, 1996)

- ^ Bukovszky, László: Mátyusföld II: Egy régió története a XI. századtól 1945-ig, Komárom, 2005

- ^ "RadixIndex : Helyek : Rete".

- ^ "Felvidék 1947 Egyesület". Archived from the original on 2 October 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ^ Teleki, József Count de Szék: Hunyadiak Kora: Magyarországon (Pest, 1863) p. 199

- ^ Bukovszky, László: Mátyusföld II.: Egy régió története a XI. századtól 1945-ig, Komarom 2005

- ^ Bukovszky, László: Matyusfold II.: Egy régió története a XI. századtól 1945-ig, Komárom, 2005

- ^ Hlavackova, Miriam. Kapitula pri Dóme sv. Martina - intelektuálne centrum Bratislavy v 15. storočí (Bratislava, 2008)

- ^ Lehotzky, Andreas: Stemmatographia Nobilium Familiarum Regni Hungariae, etc., Posonii 1796, p. 203

- ^ "Tárhely és domain regisztrálás olcsón - Cweb.hu™ - Tárhely - Domain".

- ^ Hengelmuller, Ladislas Baron von Hengervar: Hungary's Fight for National Existence, London 1913, p. 299

- ^ Az Egri Múzeum évkönyve: Dobó István Vármúzeum, 1963, p. 287

- ^ "A Pallas nagy lexikona".

- ^ Dedek Crescens, Laszlo: Pozsony vármegye története, Budapest, 1904

- ^ Liszka, József: Narodopis Madarov na Slovensku, Komarno - Dunajska Streda, 2003

- ^ "Budapest Főváros Levéltára |".

- ^ "Öngyilkos lett Pomichal Richárd | Új Szó Online". Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ^ "Csehszlovákia és Magyarország viszonya az 1920−as években" [Relations between Czechoslovakia and Hungary in the 1920s] (PDF) (in Hungarian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ "37 - Pomichal István (Fél)". Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ^ Bel Matthias: Notitia Hungariae Novae, Partis Secundae, Cis-Danubiane, Tomus Secundus (1736), p. 189

- ^ Vályi András (1796). "A magyar szociológiatörténet klasszikusai" [Classics of Hungarian Sociological History]. Magyar Országnak leírása (in Hungarian). Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

- ^ Fényes, Elek (1851). Magyarország geographiai szótára (in Hungarian).

- ^ Liszka, J (2003). "Narodopis Madarov na Slovensku" (PDF). p. 231.

- ^ "Lieutenant Rakoczy". IMDb.

- ^ "Rákóczi hadnagya" [Rákóczi's lieutenant] (in Hungarian).

External links

[edit]- http://www.statistics.sk/mosmis/eng/run.html Archived 2007-11-16 at the Wayback Machine