Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Rimmon

View on WikipediaRimmon or Rimon (Hebrew: רִמּוֹן, romanized: Rīmmōn) is a Hebrew word meaning 'pomegranate'. It appears as a name in the Hebrew Bible where, when translated to Greek, it takes the form Remmon Ρεμμων, Remmōn).

Rimmon ("pomegranate" in Hebrew)[1][2] was a Syrian deity mentioned in the Second Book of Kings (2 Kings 5:18), to whom a temple was dedicated. In Syria, this storm god was also known as Hadad (interpreted to mean "the breast" in Biblical Hebrew)[3][4] or Baal ("the Lord"), and in Assyria as Ramanu ("the thunderer", when borrowed from Akkadian - cf. Akkadian ramanu, "to roar").[1]

Hebrew Bible

[edit]Place-names

[edit]Rimmon may refer to:

- Rimmon, one of the "uttermost cities" of Judah, afterwards given to Simeon (Joshua 15:21, 32; 19:7; 1 Chronicles 4:32). In Joshua 15:32, Ain and Rimmon are mentioned separately, but in Joshua 19:7 and 1 Chronicles 4:32 the two words are probably to be combined, as forming together the name of one place, Ain-Rimmon = "the spring of the pomegranate" (compare Nehemiah 11:29). It has been identified with Um er-Rumamin, about 13 miles south-west of Hebron. Zechariah 14:10 describes it as "south of Jerusalem," to distinguish it from other Rimmons; and uses it in conjunction with Geba to describe the latitudinal span of the kingdom of Judah.

- The Rock of Rimmon, where the Benjamites fled (Judges 20:45, 47; 21:13), and where they maintained themselves for four months after the battle at Gibeah. It is the present village of Rammun, "on the very edge of the hill country, with a precipitous descent toward the Jordan valley", supposed to be the site of Ai.[5] Israeli settlement Rimonim nearby is named after the biblical place.

- Hadad-Rimmon near Megiddo

Biblical figure

[edit]Rimon is mentioned as a man of Beeroth of the tribe of Benjamin, whose two sons, Baanah and Rechab, were captains of the army of Ish-bosheth, son of King Saul.[6]

Syrian deity

[edit]Rimmon ("pomegranate" in Hebrew)[1][7] was a Syrian deity mentioned in the Second Book of Kings (2 Kings 5:18), to whom a temple was dedicated. In Syria, this storm god was also known as Hadad (interpreted to mean "the breast" in Biblical Hebrew)[8][9] or Baal ("the Lord"), and in Assyria as Ramanu ("the thunderer", when borrowed from Akkadian - cf. Akkadian ramanu, "to roar").[1]

According to the biblical narrative, the Aramean commander Naaman, having been healed of his leprosy by the Israelite prophet Elisha, requested pardon from God for continuing to minister to the King of Syria who would continue to worship in the Temple of Rimmon. Elisha granted him this pardon.[10]

Extra-biblical usage

[edit]- An adornment of the Torah scroll (usually plural: Torah rimonim), from the Hebrew word for pomegranate.

- "Rimmon", a poem by Rudyard Kipling written in 1903 after the Boer War.[11]

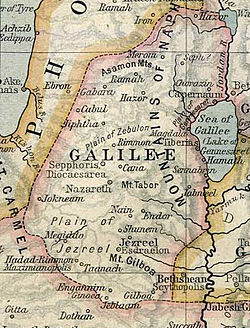

- According to The Urantia Book, allegedly revealed by celestial beings and published in 1955 in the US, Rimmon was a small city in the region of Galilee which "had once been dedicated to the worship of a Babylonian god of the air, Ramman"[12] (see Hadad/Ramman).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Tenney, Merrill C., ed. (1975). "Rimmon". Rimmon - Encyclopedia of the Bible - Bible Gateway. The Zondervan Pictorial Encyclopedia of the Bible. Retrieved 29 July 2024 – via BibleGateway. Citing A. Saarisalo, Topographical Researches in Galilee, JPOS, IX (1929), pp. 27-40; F.-M. Abel, Géographie de la Palestine, II (1938), pp. 437 and passim; W. F. Albright, The List of Levitic Cities, Louis Ginzberg Jubilee Volume (1945), English section, pp. 49-73; Y. Aharoni, The Land of the Bible (1967).

- ^ Klein, Reuven Chaim (2018). God versus Gods: Judaism in the Age of Idolatry. Mosaica Press. pp. 351–354. ISBN 978-1946351463. OL 27322748M. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ Klein, Reuven Chaim (August 2017). "Nursing from the Good". What's in a Word?. Ohr Somayach.

- ^ Klein (2018), pp.[323-324.

- ^ M. G. Easton (October 2006). Illustrated Bible Dictionary. Cosimo, Inc. p. 585. ISBN 978-1-59605-947-4.

- ^ 2 Samuel 4:2

- ^ Klein, Reuven Chaim (2018). God versus Gods: Judaism in the Age of Idolatry. Mosaica Press. pp. 351–354. ISBN 978-1946351463. OL 27322748M. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ Klein, Reuven Chaim (August 2017). "Nursing from the Good". What's in a Word?. Ohr Somayach.

- ^ Klein (2018), pp.[323-324.

- ^ 2 Kings 5:19

- ^ Rimmon, from Rudyard Kipling’s Verse, definitive edition, London, 1940, accessed 25 December 2017

- ^ The Urantia Book: First Preaching Tour of Galilee, paper 146:1. p. 1637.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of רימון at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of רימון at Wiktionary

Rimmon

View on GrokipediaRimmon was an ancient Near Eastern deity revered by the Syrians as a storm god, serving as an epithet for Baal-Hadad and equated with the Mesopotamian Adad.[1][2]

The name derives from the Akkadian rammanu, meaning "thunderer," underscoring Rimmon's association with thunder, rain, and atmospheric phenomena central to agricultural societies in the region.[1]

Worship of Rimmon was prominent in Damascus, where a dedicated temple—known as the house of Rimmon—housed rituals, as evidenced by the biblical account of the Syrian commander Naaman invoking the deity after his healing by the prophet Elisha.[3][1]

This integration into Aramean religious practice highlights the syncretic nature of ancient Semitic pantheons, blending local traditions with broader Mesopotamian influences, though Hebrew scriptures portray Rimmon as a foreign idol contrasting with monotheistic Yahwism.[2][1]