Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Rod calculus

View on WikipediaRod calculus or rod calculation was the mechanical method of algorithmic computation with counting rods in China from the Warring States to Ming dynasty before the counting rods were increasingly replaced by the more convenient and faster abacus. Rod calculus played a key role in the development of Chinese mathematics to its height in the Song dynasty and Yuan dynasty, culminating in the invention of polynomial equations of up to four unknowns in the work of Zhu Shijie.

Hardware

[edit]The basic equipment for carrying out rod calculus is a bundle of counting rods and a counting board. The counting rods are usually made of bamboo sticks, about 12 cm- 15 cm in length, 2mm to 4 mm diameter, sometimes from animal bones, or ivory and jade (for well-heeled merchants). A counting board could be a table top, a wooden board with or without grid, on the floor or on sand.

In 1971 Chinese archaeologists unearthed a bundle of well-preserved animal bone counting rods stored in a silk pouch from a tomb in Qian Yang county in Shanxi province, dated back to the first half of Han dynasty (206 BC – 8AD).[citation needed] In 1975 a bundle of bamboo counting rods was unearthed.[citation needed]

The use of counting rods for rod calculus flourished in the Warring States, although no archaeological artefacts were found earlier than the Western Han dynasty (the first half of Han dynasty; however, archaeologists did unearth software artefacts of rod calculus dated back to the Warring States); since the rod calculus software must have gone along with rod calculus hardware, there is no doubt that rod calculus was already flourishing during the Warring States more than 2,200 years ago.

Software

[edit]The key software required for rod calculus was a simple 45 phrase positional decimal multiplication table used in China since antiquity, called the nine-nine table, which were learned by heart by pupils, merchants, government officials and mathematicians alike.

Rod numerals

[edit]Displaying numbers

[edit]

Rod numerals is the only numeric system that uses different placement combination of a single symbol to convey any number or fraction in the Decimal System. For numbers in the units place, every vertical rod represent 1. Two vertical rods represent 2, and so on, until 5 vertical rods, which represents 5. For number between 6 and 9, a biquinary system is used, in which a horizontal bar on top of the vertical bars represent 5. The first row are the number 1 to 9 in rod numerals, and the second row is the same numbers in horizontal form.

For numbers larger than 9, a decimal system is used. Rods placed one place to the left of the units place represent 10 times that number. For the hundreds place, another set of rods is placed to the left which represents 100 times of that number, and so on. As shown in the adjacent image, the number 231 is represented in rod numerals in the top row, with one rod in the units place representing 1, three rods in the tens place representing 30, and two rods in the hundreds place representing 200, with a sum of 231.

When doing calculation, usually there was no grid on the surface. If rod numerals two, three, and one is placed consecutively in the vertical form, there's a possibility of it being mistaken for 51 or 24, as shown in the second and third row of the adjacent image. To avoid confusion, number in consecutive places are placed in alternating vertical and horizontal form, with the units place in vertical form,[1] as shown in the bottom row on the right.

Displaying zeroes

[edit]In Rod numerals, zeroes are represented by a space, which serves both as a number and a place holder value. Unlike in Hindu-Arabic numerals, there is no specific symbol to represent zero. Before the introduction of a written zero, in addition to a space to indicate no units, the character in the subsequent unit column would be rotated by 90°, to reduce the ambiguity of a single zero.[2] For example 107 (𝍠 𝍧) and 17 (𝍩𝍧) would be distinguished by rotation, in addition to the space, though multiple zero units could lead to ambiguity, e.g. 1007 (𝍩 𝍧), and 10007 (𝍠 𝍧). In the adjacent image, the number zero is merely represented with a space.

Negative and positive numbers

[edit]Song mathematicians used red to represent positive numbers and black for negative numbers. However, another way is to add a slash to the last place to show that the number is negative.[3]

Decimal fraction

[edit]The Mathematical Treatise of Sunzi used decimal fraction metrology. The unit of length was 1 chi,

1 chi = 10 cun, 1 cun = 10 fen, 1 fen = 10 li, 1 li = 10 hao, 10 hao = 1 shi, 1 shi = 10 hu.

1 chi 2 cun 3 fen 4 li 5 hao 6 shi 7 hu is laid out on counting board as

where ![]() is the unit measurement chi.

is the unit measurement chi.

Southern Song dynasty mathematician Qin Jiushao extended the use of decimal fraction beyond metrology. In his book Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections, he formally expressed 1.1446154 day as

He marked the unit with a word “日” (day) underneath it.[4]

Addition

[edit]

Rod calculus works on the principle of addition. Unlike Arabic numerals, digits represented by counting rods have additive properties. The process of addition involves mechanically moving the rods without the need of memorising an addition table. This is the biggest difference with Arabic numerals, as one cannot mechanically put 1 and 2 together to form 3, or 2 and 3 together to form 5.

The adjacent image presents the steps in adding 3748 to 289:

- Place the augend 3748 in the first row, and the addend 289 in the second.

- Calculate from LEFT to RIGHT, from the 2 of 289 first.

- Take away two rods from the bottom add to 7 on top to make 9.

- Move 2 rods from top to bottom 8, carry one to forward to 9, which becomes zero and carries to 3 to make 4, remove 8 from bottom row.

- Move one rod from 8 on top row to 9 on bottom to form a carry one to next rank and add one rod to 2 rods on top row to make 3 rods, top row left 7.

- Result 3748+289=4037

The rods in the augend change throughout the addition, while the rods in the addend at the bottom "disappear".

Subtraction

[edit]

Without borrowing

[edit]In situation in which no borrowing is needed, one only needs to take the number of rods in the subtrahend from the minuend. The result of the calculation is the difference. The adjacent image shows the steps in subtracting 23 from 54.

Borrowing

[edit]In situations in which borrowing is needed such as 4231–789, one need use a more complicated procedure. The steps for this example are shown on the left.

- Place the minuend 4231 on top, the subtrahend 789 on the bottom. Calculate from the left to the right.

- Borrow 1 from the thousands place for a ten in the hundreds place, minus 7 from the row below, the difference 3 is added to the 2 on top to form 5. The 7 on the bottom is subtracted, shown by the space.

- Borrow 1 from the hundreds place, which leaves 4. The 10 in the tens place minus the 8 below results in 2, which is added to the 3 above to form 5. The top row now is 3451, the bottom 9.

- Borrow 1 from the 5 in the tens place on top, which leaves 4. The 1 borrowed from the tens is 10 in the units place, subtracting 9 which results in 1, which are added to the top to form 2. With all rods in the bottom row subtracted, the 3442 in the top row is then, the result of the calculation

Multiplication

[edit]

Sunzi Suanjing described in detail the algorithm of multiplication. On the left are the steps to calculate 38×76:

- Place the multiplicand on top, the multiplier on bottom. Line up the units place of the multiplier with the highest place of the multiplicand. Leave room in the middle for recording.

- Start calculating from the highest place of the multiplicand (in the example, calculate 30×76, and then 8×76). Using the multiplication table 3 times 7 is 21. Place 21 in rods in the middle, with 1 aligned with the tens place of the multiplier (on top of 7). Then, 3 times 6 equals 18, place 18 as it is shown in the image. With the 3 in the multiplicand multiplied totally, take the rods off.

- Move the multiplier one place to the right. Change 7 to horizontal form, 6 to vertical.

- 8×7 = 56, place 56 in the second row in the middle, with the units place aligned with the digits multiplied in the multiplier. Take 7 out of the multiplier since it has been multiplied.

- 8×6 = 48, 4 added to the 6 of the last step makes 10, carry 1 over. Take off 8 of the units place in the multiplicand, and take off 6 in the units place of the multiplier.

- Sum the 2380 and 508 in the middle, which results in 2888: the product.

Division

[edit]

The animation on the left shows the steps for calculating 309/7 = 441/7.

- Place the dividend, 309, in the middle row and the divisor, 7, in the bottom row. Leave space for the top row.

- Move the divisor, 7, one place to the left, changing it to horizontal form.

- Using the Chinese multiplication table and division, 30÷7 equals 4 remainder 2. Place the quotient, 4, in the top row and the remainder, 2, in the middle row.

- Move the divisor one place to the right, changing it to vertical form. 29÷7 equals 4 remainder 1. Place the quotient, 4, on top, leaving the divisor in place. Place the remainder in the middle row in place of the dividend in this step. The result is the quotient is 44 with a remainder of 1

The Sunzi algorithm for division was transmitted in toto by al Khwarizmi to Islamic country from Indian sources in 825AD. Al Khwarizmi's book was translated into Latin in the 13th century, The Sunzi division algorithm later evolved into Galley division in Europe. The division algorithm in Abu'l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi's 925AD book Kitab al-Fusul fi al-Hisab al-Hindi and in 11th century Kushyar ibn Labban's Principles of Hindu Reckoning were identical to Sunzu's division algorithm.

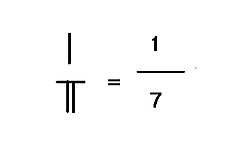

Fractions

[edit]If there is a remainder in a place value decimal rod calculus division, both the remainder and the divisor must be left in place with one on top of another. In Liu Hui's notes to Jiuzhang suanshu (2nd century BCE), the number on top is called "shi" (实), while the one at bottom is called "fa" (法). In Sunzi Suanjing, the number on top is called "zi" (子) or "fenzi" (lit., son of fraction), and the one on the bottom is called "mu" (母) or "fenmu" (lit., mother of fraction). Fenzi and Fenmu are also the modern Chinese name for numerator and denominator, respectively. As shown on the right, 1 is the numerator remainder, 7 is the denominator divisor, formed a fraction 1/7. The quotient of the division 309/7 is 44 + 1/7. Liu Hui used a lot of calculations with fractions in Haidao Suanjing.

This form of fraction with numerator on top and denominator at bottom without a horizontal bar in between, was transmitted to Arabic country in an 825AD book by al Khwarizmi via India, and in use by 10th century Abu'l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi and 15th century Jamshīd al-Kāshī's work "Arithematic Key".

Addition

[edit]

1/3 + 2/5

- Put the two numerators 1 and 2 on the left side of counting board, put the two denominators 3 and 5 at the right hand side

- Cross multiply 1 with 5, 2 with 3 to get 5 and 6, replace the numerators with the corresponding cross products.

- Multiply the two denominators 3 × 5 = 15, put at bottom right

- Add the two numerators 5 and 6 = 11 put on top right of counting board.

- Result: 1/3 + 2/5 = 11/15

Subtraction

[edit]

8/9 − 1/5

- Put down the rod numeral for numerators 1 and 8 at left hand side of a counting board

- Put down the rods for denominators 5 and 9 at the right hand side of a counting board

- Cross multiply 1 × 9 = 9, 5 × 8 = 40, replace the corresponding numerators

- Multiply the denominators 5 × 9 = 45, put 45 at the bottom right of counting board, replace the denominator 5

- Subtract 40 − 9 = 31, put on top right.

- Result: 8/9 − 1/5 = 31/45

Multiplication

[edit]

31/3 × 52/5

- Arrange the counting rods for 31/3 and 52/5 on the counting board as shang, shi, fa tabulation format.

- shang times fa add to shi: 3 × 3 + 1 = 10; 5 × 5 + 2 = 27

- shi multiplied by shi:10 × 27 = 270

- fa multiplied by fa:3 × 5 = 15

- shi divided by fa: 31/3 × 52/5 = 18

Highest common factor and fraction reduction

[edit]

The algorithm for finding the highest common factor of two numbers and reduction of fraction was laid out in Jiuzhang suanshu. The highest common factor is found by successive division with remainders until the last two remainders are identical. The animation on the right illustrates the algorithm for finding the highest common factor of 32,450,625/59,056,400 and reduction of a fraction.

In this case the hcf is 25.

Divide the numerator and denominator by 25. The reduced fraction is 1,298,025/2,362,256.

Interpolation

[edit]

Calendarist and mathematician He Chengtian (何承天) used fraction interpolation method, called "harmonisation of the divisor of the day" (调日法) to obtain a better approximate value than the old one by iteratively adding the numerators and denominators a "weaker" fraction with a "stronger fraction".[5] Zu Chongzhi's legendary π = 355/113 could be obtained with He Chengtian's method[6]

System of linear equations

[edit]

Chapter Eight Rectangular Arrays of Jiuzhang suanshu, provided an algorithm for solving System of linear equations by method of elimination:[7]

Problem 8-1: Suppose we have 3 bundles of top quality cereals, 2 bundles of medium quality cereals, and a bundle of low quality cereal with accumulative weight of 39 dou. We also have 2, 3 and 1 bundles of respective cereals amounting to 34 dou; we also have 1,2 and 3 bundles of respective cereals, totaling 26 dou.

Find the quantity of top, medium, and poor quality cereals. In algebra, this problem can be expressed in three system equations with three unknowns.

This problem was solved in Jiuzhang suanshu with counting rods laid out on a counting board in a tabular format similar to a 3x4 matrix:

| quality | left column | center column | right column |

|---|---|---|---|

| top | |||

| medium | |||

| low | |||

| shi |

Algorithm:

- Multiply the center column with right column top quality number.

- Repeatedly subtract right column from center column, until the top number of center column=0.

- multiply the left column with the value of top row of right column.

- Repeatedly subtract right column from left column, until the top number of left column=0.

- After applying above elimination algorithm to the reduced center column and left column, the matrix was reduced to triangular shape.

| quality | left column | center column | right column |

|---|---|---|---|

| top | |||

| medium | |||

| low | |||

| shi |

The amount of one bundle of low quality cereal

From which the amount of one bundle of top and medium quality cereals can be found easily:

- One bundle of top quality cereals=9 dou

- One bundle of medium cereal=4 dou

Extraction of Square root

[edit]Algorithm for extraction of square root was described in Jiuzhang suanshu and with minor difference in terminology in Sunzi Suanjing.

The animation shows the algorithm for rod calculus extraction of an approximation of the square root from the algorithm in chap 2 problem 19 of Sunzi Suanjing:

- Now there is a square area 234567, find one side of the square.[8]

The algorithm is as follows:

- Set up 234567 on the counting board, on the second row from top, named shi

- Set up a marker 1 at 10000 position at the 4th row named xia fa

- Estimate the first digit of square root to be counting rod numeral 4, put on the top row (shang) hundreds position,

- Multiply the shang 4 with xiafa 1, put the product 4 on 3rd row named fang fa

- Multiply shang with fang fa deduct the product 4x4=16 from shi: 23-16=7, remain numeral 7.

- double up the fang fa 4 to become 8, shift one position right, and change the vertical 8 into horizontal 8 after moved right.

- Move xia fa two position right.

- Estimate second digit of shang as 8: put numeral 8 at tenth position on top row.

- Multiply xia fa with the new digit of shang, add to fang fa

.

- 8 calls 8 =64, subtract 64 from top row numeral "74", leaving one rod at the most significant digit.

- double the last digit of fang fa 8, add to 80 =96

- Move fang fa96 one position right, change convention;move xia fa "1" two position right.

- Estimate 3rd digit of shang to be 4.

- Multiply new digit of shang 4 with xia fa 1, combined with fang fa to make 964.

- subtract successively 4*9=36,4*6=24,4*4=16 from the shi, leaving 311

- double the last digit 4 of fang fa into 8 and merge with fang fa

- result

North Song dynasty mathematician Jia Xian developed an additive multiplicative algorithm for square root extraction, in which he replaced the traditional "doubling" of "fang fa" by adding shang digit to fang fa digit, with same effect.

Extraction of cubic root

[edit]

Jiuzhang suanshu vol iv "shaoguang" provided algorithm for extraction of cubic root.

〔一九〕今有積一百八十六萬八百六十七尺。問為立方幾何?答曰:一百二十三尺。

problem 19: We have a 1860867 cubic chi, what is the length of a side ? Answer:123 chi.

North Song dynasty mathematician Jia Xian invented a method similar to simplified form of Horner scheme for extraction of cubic root. The animation at right shows Jia Xian's algorithm for solving problem 19 in Jiuzhang suanshu vol 4.

Polynomial equation

[edit]

North Song dynasty mathematician Jia Xian invented Horner scheme for solving simple 4th order equation of the form

South Song dynasty mathematician Qin Jiushao improved Jia Xian's Horner method to solve polynomial equation up to 10th order. The following is algorithm for solving

- in his Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections vol 6 problem 2.[9]

This equation was arranged bottom up with counting rods on counting board in tabular form

| 0 | shang | root |

|---|---|---|

| 626250625 | shi | constant |

| 0 | fang | coefficient of x |

| 15245 | shang lian | positive coef of |

| 0 | fu lian | negative coef of |

| 0 | xia lian | coef of |

| 1 | yi yu | negative coef of |

Algorithm:

- Arrange the coefficients in tabular form, constant at shi, coeffienct of x at shang lian, the coeffiecnt of at yi yu;align the numbers at unit rank.

- Advance shang lian two ranks

- Advance yi yu three ranks

- Estimate shang=20

- let xia lian =shang * yi yu

- let fu lian=shang *yi yu

- merge fu lian with shang lian

- let fang=shang * shang lian

- subtract shang*fang from shi

- add shang * yi yu to xia lian

- retract xia lian 3 ranks, retract yi yu 4 ranks

- The second digit of shang is 0

- merge shang lian into fang

- merge yi yu into xia lian

- Add yi yu to fu lian, subtract the result from fang, let the result be denominator

- find the highest common factor =25 and simplify the fraction

- solution

Tian Yuan shu

[edit]

Yuan dynasty mathematician Li Zhi developed rod calculus into Tian yuan shu

Example Li Zhi Ceyuan haijing vol II, problem 14 equation of one unknown:

Polynomial equations of four unknowns

[edit]

Mathematician Zhu Shijie further developed rod calculus to include polynomial equations of 2 to four unknowns.

For example, polynomials of three unknowns:

Equation 1:

Equation 2:

Equation 3:

After successive elimination of two unknowns, the polynomial equations of three unknowns was reduced to a polynomial equation of one unknown:

Solved x=5;

Which ignores 3 other answers, 2 are repeated.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ronan and Needham, The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China, vol 2, Chapter 1, Mathematics

- ^ "Chinese numerals". Maths History. Retrieved 2024-04-28.

- ^ *Ho Peng Yoke, Li, Qi and Shu ISBN 0-486-41445-0

- ^ Lam Lay Yong, p87-88

- ^ Jean claude Martzloff, A History of Chinese Mathematics p281

- ^ Wu Wenjun ed Grand Series of History of Chinese Mathematics vol 4 p125

- ^ Jean-Claude Martzloff, A History of Chinese Mathematics, p249-257

- ^ Lay Lay Yong, Ang Tian Se, Fleeting Footsteps, p66-73

- ^ Jean Claude Martzloff, A History of Chinese Mathematics, p233-246

- Lam Lay Yong (蓝丽蓉) Ang Tian Se (洪天赐), Fleeting Footsteps, World Scientific ISBN 981-02-3696-4

- Jean Claude Martzloff, A History of Chinese Mathematics ISBN 978-3-540-33782-9

Rod calculus

View on GrokipediaHistory and Development

Origins in Ancient China

Rod calculus traces back to at least the Spring and Autumn period (around 8th century BCE), emerging as a positional numeral system in ancient China, employing small rods typically made from bamboo or wood to represent digits and perform calculations on a flat surface. This method originated during the Warring States period (475–221 BCE), where rods were arranged horizontally or vertically to denote numbers in a decimal framework, allowing for efficient arithmetic beyond simple enumeration.[1][4] Archaeological evidence supports this early development, including the discovery of 61 ivory counting rods unearthed between 2004 and 2008 at the Qin Mausoleum in Xi'an, Shaanxi Province, dating to the late Warring States period. These artifacts, measuring approximately 18 cm in length and featuring red-and-white or red-and-black color schemes to distinguish positive and negative values, indicate practical use in recording gains and losses. Earlier bamboo rod examples were found in 1954 at a tomb in Changsha, Hunan Province, while additional rod-like items from Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) tombs, such as wooden scripts excavated in 1973 from a Hubei site, further attest to the system's prevalence by the early imperial era.[4][5] Initially, rod calculus evolved from tally stick methods used for basic counting in daily life, trade, and administrative records, transitioning to a more versatile tool for handling quantities in commerce and governance without relying on written characters alone. Although the practice predates surviving texts, the earliest explicit textual references appear in The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art (c. 100 BCE), a Han dynasty compilation that describes rod-based procedures for operations like finding the greatest common divisor. This foundational system later influenced subsequent works, such as the Sunzi Suanjing.[4][6]Key Texts and Mathematicians

The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art (Jiuzhang suanshu), compiled around 200 BCE during the Han dynasty, serves as the foundational text for rod calculus, presenting 246 practical problems across nine categories including land surveying, proportions, progressions, square and cube roots, volumes, fair distribution, excess and deficit analysis, linear equations via square tables, and right-angled triangles, all solved using counting rods on a board.[7] This work systematized rod-based methods for arithmetic and geometry, influencing Chinese mathematics for over a millennium.[7] In the 3rd century CE, Liu Hui provided a seminal commentary on the Nine Chapters, expanding its techniques with rod calculus proofs for geometric theorems, such as areas of circles and volumes of pyramids and spheres, employing the method of exhaustion to derive results like the pyramid volume formula through iterative rod arrangements.[7] His annotations, completed around 263 CE, introduced rigorous demonstrations absent in the original, enhancing the text's theoretical depth while preserving its practical rod applications.[8] Subsequent texts built on these foundations; the Sunzi Suanjing (Master Sun's Mathematical Manual), dated to the 3rd–5th century CE, focuses on arithmetic problems like fractions, areas, volumes, and the Chinese Remainder Theorem, detailing rod placements for multiplication and division on counting boards.[9] Similarly, Zhang Qiujian's Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections (Zhang Qiujian suanjing), composed around 466 CE, advances rod calculus through 75 problems on arithmetic progressions, least common multiples, and systems of equations, offering innovative applications in taxation and trade.[10] In the 11th century, Jia Xian introduced rod methods for extracting higher roots (beyond squares and cubes) in his lost work Shi Suo Suan Fa, generalizing iterative techniques using counting rods to solve polynomial equations of degree n > 3, a precursor to later algebraic advancements.[11]Spread and Regional Variations

Rod calculus, originating in China, spread to neighboring regions through cultural and scholarly exchanges, particularly during periods of strong Sino-Korean and Sino-Japanese interactions. In Korea, the system was transmitted during the Goryeo dynasty (918–1392 CE), facilitated by Buddhist monks who brought Chinese mathematical knowledge amid the dynasty's close ties with the Song dynasty. This adoption supported administrative calculations in state bureaucracy and astronomy, aligning with Goryeo's emphasis on eastern mathematical traditions like counting rod methods. Korean mathematics during this era focused on rod-based computation, preserving and adapting Chinese techniques even as some advanced topics waned in China itself. Counting rods known as sangi were typically wooden, similar to Chinese variants.[12][13][14] The practice reached Japan by the Edo period (1603–1868 CE), where it influenced the evolution of local computing tools. Japanese mathematicians, known as wasan scholars, employed sangi (counting rods) on calculation boards for complex arithmetic and algebraic problems, integrating the method into precursors of the soroban abacus. This period saw rod calculus embedded in educational and practical applications, from commerce to scientific inquiry, before the soroban largely supplanted physical rods. A notable later development was anzan, a mental visualization technique based on the soroban abacus, which extended the legacy of earlier rod-based methods by enabling rapid mental arithmetic without physical tools.[15] Regional adaptations highlighted practical innovations. Meanwhile, the Japanese focus on anzan extended rod calculus's legacy by prioritizing cognitive mastery over material tools, enabling portability and rapid mental arithmetic that persisted into modern training methods.[14] In China, rod calculus began to decline by the 16th century during the Ming dynasty, overtaken by the more portable and versatile suanpan abacus, which simplified multi-step operations without rearranging rods. However, the system's influence endured in Japan, where sangi-based methods and their mental extensions remained in use until the early 20th century, outlasting the physical practice in its origin country.[16]Physical Components

Counting Rods

Counting rods, the fundamental tools of rod calculus, were typically crafted from lightweight, durable materials such as bamboo, wood, animal bone, ivory, or jade to facilitate precise manipulation during computations.[4] These rods measured approximately 12–15 cm in length and 2–4 mm in thickness, allowing them to be easily arranged and rearranged without excessive bulk.[4] Archaeological excavations from ancient tombs have uncovered well-preserved examples, including bundles of bone and ivory rods, confirming their widespread use across dynasties.[4] To distinguish numerical signs, rods were often painted in contrasting colors: red for positive values and black for negative ones, enhancing visibility and reducing errors in complex operations.[17] This color coding, documented in classical mathematical texts, reflected the system's early handling of signed quantities.[17] Functionally, rods were oriented vertically for the units place, horizontally for the tens place, vertically for the hundreds place, horizontally for the thousands place, and so on, alternating for each successive place value to distinguish positions in the decimal system.[18] In practice, these reusable rods were placed on a flat calculation surface, such as a wooden board or table divided into grids, where they formed visual representations of multi-digit numbers for arithmetic tasks.[18] The portability and simplicity of the rods allowed mathematicians to perform calculations dynamically, moving and combining them as needed, which underscored their role as versatile hardware in ancient Chinese computation.[18]Calculation Surfaces and Tools

The primary calculation surface for rod calculus was the counting board, a grid-like structure designed to align counting rods according to positional notation. These boards, in use as early as 400 BCE during the Warring States period, were typically constructed from polished wood with incised rulings forming a checkerboard pattern of square cells, enabling precise placement of rods in columns to denote units, tens, hundreds, and higher decimal places.[19][20] Mats or similar flat surfaces occasionally substituted for wooden boards in less formal settings, maintaining the grid alignment essential for accurate computations.[19] Accessories complemented the counting board by supporting temporary and permanent aspects of calculations. Ink and brushes were employed to transcribe results onto paper, ensuring durable records of computations once rods were cleared from the board.[19]Numeral System

Basic Digit Representation

Rod calculus utilized a decimal positional numeral system, where numbers were formed by arranging counting rods in columns corresponding to place values, from units on the right to higher powers of ten moving leftward. Each digit from 1 to 9 was encoded through specific configurations of vertical and horizontal rods, while 0 was indicated by leaving the space empty. This arrangement allowed for efficient visual distinction of values within the base-10 framework.[21] The core representations for digits relied on the number and orientation of rods: the digit 1 was a single vertical rod (┃), 2 through 4 were two to four parallel vertical rods (┃┃, ┃┃┃, ┃┃┃┃), and 5 was a single horizontal rod (━). Digits 6 to 9 combined the horizontal rod for 5 with one to four vertical rods for the remainder, typically positioned such that the horizontal rod lay above or adjacent to the vertical ones (e.g., ━┃ for 6, ━┃┃ for 7). These shapes formed the basic building blocks, with the empty space serving as 0 to maintain positional integrity without additional markers.[22][23] Place values were differentiated by alternating the predominant rod orientation across columns, ensuring clarity in multi-digit numbers. In the units column (rightmost), rods were primarily vertical for 1–4 and combinations thereof, but the tens column (adjacent left) used primarily horizontal rods for 1–4, a vertical rod for 5, and vertical-plus-horizontal combinations for 6–9. This pattern repeated, with hundreds reverting to vertical-dominant like units. Such orientation shifts prevented ambiguity, as a vertical rod in the units column signified ones while the same in the tens column would denote fives.[21][23] A representative example is the number 123, depicted as follows on the calculation surface:- Units (vertical orientation): three vertical rods (┃┃┃) for 3

- Tens (horizontal orientation): two horizontal rods (━━) for 2

- Hundreds (vertical orientation): one vertical rod (┃) for 1

Zero, Signs, and Positioning

In rod calculus, zero was represented by leaving the corresponding position vacant on the calculation board, serving both as a numerical value and a placeholder to preserve place value in multi-digit numbers.[25] This blank space prevented ambiguity in positional notation, such as distinguishing between numbers like 12 and 102, though later written representations sometimes adopted a circular symbol (〇) for clarity in texts.[19] In the Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art, such blanks were essential in intermediate steps of division and linear equation solving (as in the Fangcheng procedure), ensuring alignment of powers of ten during algorithmic computations.[25] Signs for positive and negative values were indicated through color conventions on the counting rods: red rods denoted positive quantities (often termed zheng or "real"), while black rods signified negatives (fu or "false").[20] This system, elaborated in Liu Hui's third-century commentary on the Nine Chapters, allowed seamless handling of negatives in arithmetic without altering rod orientations, though some methods inverted colors or used contextual labels in equations to denote absolute values.[26] Absolute values were typically computed first, with signs applied based on operational rules, reflecting the practical needs of commerce and surveying where debts and surpluses arose naturally.[20] Positioning of rods followed a decimal place-value system arranged horizontally from right to left, with the rightmost column representing units (10^0), the next to the left tens (10^1), and so on for higher powers.[19] Rods were aligned along grid lines on the board for precision, often alternating vertical orientations for units, hundreds, etc., and horizontal for tens, thousands, etc., to distinguish place values visually.[19] This layout facilitated multi-digit operations by maintaining spatial order, building on the basic digit forms (1–9 via rod clusters) without requiring additional symbols beyond the blank for zero.[25]Fractional and Decimal Forms

In rod calculus, fractions were represented in two primary ways: common fractions and decimal fractions. Common fractions were expressed by two rod configurations placed one above the other, with the upper set representing the numerator ("son") and the lower set the denominator ("mother"), without any separating bar.[27] Decimal fractions were represented by extending the positional system beyond the units place to the right, treating fractional parts as negative powers of 10 (tenths, hundredths, etc.). No explicit decimal marker was used; the position relative to the units column indicated the decimal places, with the alternating horizontal-vertical orientations continuing into the fractional columns.[19] For instance, the value 3.25 would be depicted as follows: three vertical rods in the units column (vertical-dominant) for 3; two horizontal rods in the tenths column (horizontal-dominant) for 2; and one horizontal rod in the hundredths column (vertical-dominant) for 5.[1] Recurring decimals or approximations of irrational numbers, such as those arising in astronomical contexts, were managed through iterative rod manipulations, where successive columns were adjusted based on repeated division or extraction processes to refine the value to the desired precision. This method emphasized practical computation over exact symbolic notation. During the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE), rod calculus supported representations up to six decimal places in texts for astronomical calculations, enabling high-precision computations for calendars, planetary positions, and eclipses.[19]Basic Arithmetic

Addition Techniques

In rod calculus, addition involves arranging the counting rods representing the addends on a calculation surface, such as a counting board, in a positional decimal system where each column corresponds to a power of ten. The rods for each addend are placed in parallel rows, aligned by place value, with vertical rods typically used for units, horizontal for tens, and alternating orientations for higher places to distinguish positions. Rods in corresponding columns are then combined by merging them into a single representation per column, starting from the rightmost (units) column and proceeding leftward.[19] If the total number of rods in a column exceeds nine, a carry-over is performed: ten rods are removed from that column (leaving the remainder of zero to nine) and one rod is added to the next higher column. This process leverages the decimal nature of the system, ensuring efficient summation without exceeding the representational capacity of each position, which is limited to nine rods. The method is tactile and visual, allowing for quick verification by counting the final rod configurations.[19] For example, to add 1234 and 4567 using counting rods:- In the units column: 4 + 7 = 11 rods; retain 1 rod and carry 1 to the tens column.

- In the tens column: 3 + 6 + 1 (carry) = 10 rods; retain 0 rods and carry 1 to the hundreds column.

- In the hundreds column: 2 + 5 + 1 (carry) = 8 rods; no carry.

- In the thousands column: 1 + 4 = 5 rods; no carry.

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{3}]{1860867}}=123}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6b546524683588f789435df4b594458b77b8267a)