Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

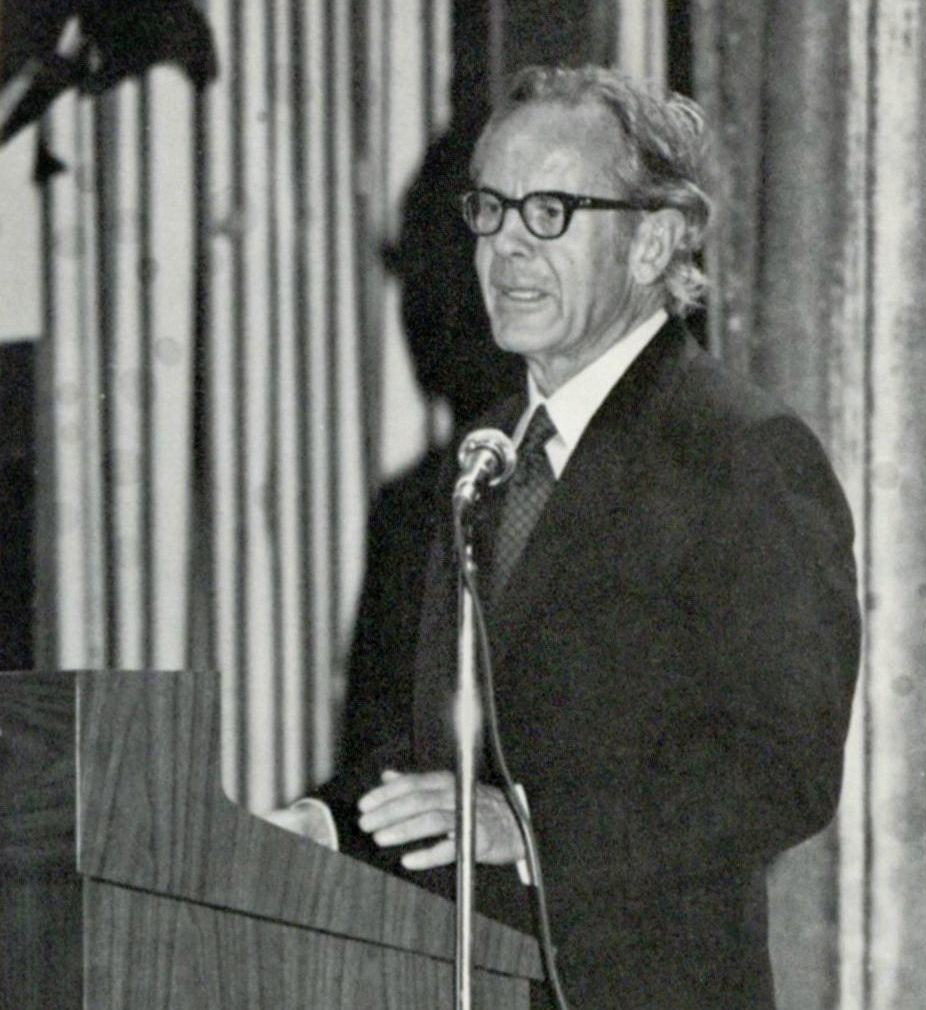

Rollo May

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Rollo Reece May (April 21, 1909 – October 22, 1994) was an American existential psychologist and author of the influential book Love and Will (1969). He is often associated with humanistic psychology and existentialist philosophy, and alongside Viktor Frankl, was a major proponent of existential psychotherapy. The philosopher and theologian Paul Tillich was a close friend who had a significant influence on his work.[1][2]

Key Information

May's other works include The Meaning of Anxiety (1950, revised 1977) and The Courage to Create (1975), named after Tillich's The Courage to Be.[3]

Early life

[edit]Reese May, otherwise known as 'Rollo' May, was born in Ada, Ohio, on April 21, 1909 to Matie Boughton and Earl Tittle May, a Men's Christian Associations Field Secretary, as the first son and the second eldest of six.[4]

His namesake 'Rollo', or, as his Mother called him, 'Little Rollo', was the title character from a series of children's' books.[5] written by Jacob Abbott in the 19th century.[6] Rollo was reported to have an intense dislike for this nickname; however, he made his peace with the moniker after learning about Rollo the Conqueror, a tenth century Norman.[5]

Some may describe Rollo's childhood as difficult due to the divorce of his parents and to his oldest sister's struggle with mental health that resulted in frequent hospitalizations.[6] His mother often left the children alone, and with his sister suffering from schizophrenia, he bore much of the burden.[7] At Michigan State University he majored in English, but was expelled due to his involvement in a radical student magazine. After that, he attended Oberlin College and received a bachelor's degree in English. He spent three years teaching in Greece at Anatolia College. During this time, he studied with doctor and psychotherapist Alfred Adler, with whom his later work shares theoretical similarities. He was ordained as a minister shortly after coming back to the United States, but left the ministry after several years to pursue a degree in psychology. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1942 and spent 18 months in a sanatorium. He later attended Union Theological Seminary for a BD during 1938, and Teachers College, Columbia University for a PhD in clinical psychology in 1949. May was a founder and faculty member of Saybrook Graduate School and Research Center in San Francisco.[8]

He spent the final years of his life in Tiburon on San Francisco Bay. May died of congestive heart failure at the age of 85,[9] attended by his wife, Georgia, and friends.[7]

Writings

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2024) |

Earlier years (1940s–1950s)

[edit]When beginning his first books, May's topics focused on more practical uses regarding patients and mental health. His first book, The Art of Counseling (1939)[10] talks about his experience of counseling. Some of the topics he looks at are empathy, religion, personality problems and mental health. May also gives his perspective on these and also discusses how to handle those particular types of issues should a counselor encounter them (May 1965). He followed with a more theoretical book, The Springs of Creative Living: A Study of Human Nature and God (1940) presenting a personality theory influenced by critiquing the work of others, including Freud and Adler. He claims that personality is deeper than they presented. This is also where May introduces his own meaning for different terms such as libido from Freudian Psychology (May, 1940).

His writings were interrupted in the 1940s due to being diagnosed with tuberculosis and having to work on his PhD.

His later books in the 1950s all focus on mental health. The Meaning of Anxiety (1950) explores anxiety and how it can affect mental health. May also discusses how he thinks that experiencing anxiety can aid development and how dealing with it appropriately can lead to having a healthy personality. In Man’s Search for Himself (1953), May talks about his experience with his patients and the recurring problems they had in common such as loneliness and emptiness. May looks deeper into this and discusses how humans have an innate need for a sense of value and also how life can often present an overwhelming sense of anxiety. May also gives signposts on how to act during these periods. (May, 1953). May's final writing in the 1950s Existence (1958) is not entirely by May, but he examines the roots of Existential Psychology and why Existential Psychology is important in understanding a gap in human understanding of the nature of existence. He also talks about the Existential Psychotherapy and the contributions it has made. (May, Ernest, Ellenberger & Aronson, 1958)

May uses this book to reflect on a lot of both his ideas so far and those of other thinkers and also mentions some contemporary ideas despite the book's publication date. May also expands on some of his previous perspectives such as anxiety and people's feelings of insignificance (May, 1967).

One of May's most influential books. He talks about his perspective on love and the Daimonic; how it is part of nature and not the superego. May also discusses how love and sex are in conflict with each other and how they are two different things. May also discusses depression and creativity towards the end. Some of the views in this book are the ones that May is best known for (May, 1969).

May uses this book to start some new ideas and also define words according to his way of thinking; such as power and physical courage and how power holds the potential for both human goodness and human evil. Another idea May explores is civilisation stemming out of rebellion (May, 1972).

May identified Paul Tillich as one of his biggest influences and in this book May episodically recalls Tillich's life trying to focus just on the key moments over the eight chapters, taking a psychoanalytic approach to the tale (May, 1973)

Listening to our ideas and helping form the structure of our world is what our creative courage can come from; this is the main direction of May in this book. May encourages that people break the pattern in their life and face their fears to reach their full potential (May, 1975).

As the title suggests, May focuses on the area of Freedom and Destiny in this book. He examines what freedom might offer and also, comparatively, how destiny is imposing limitations on us, but also how the two have an interdependence. May draws on artists and poets and others to invoke what he is saying (May, 1981).

May draws on others' perspectives, including Freud's, to go into more detail on existential psychotherapy. Another topic May examines is how Psychoanalyses and Existentialism may have come from similar areas of thinking. There is attention paid to searching for stability with strong feelings of anxiety (May, 1983).

My Quest for Beauty (1985)

[edit]Serving as a type of memoir, May discusses his own opinions on the power of beauty. He also asserts that beauty must be both understood and also valued in the world (May, 1985).[18]

Argued in this book is May's idea that humans can use myths to help them make sense of their lives, based on case studies May uses from his patients. May discusses how this could be particularly useful to those who need direction in a confusing world (May, 1991).

Two days before May's death, he edited an advanced copy of this book. It was co-authored by Kirk Schneider and was intended to bring some life back into existential psychology. Like some previous books, this talks of existential psychotherapy and targets scholars (May & Schneider, 1995).

Accomplishments

[edit]- In 1970, May's most popular work, Love and Will (1969), won the Ralph Waldo Emerson Award for humane scholarship and became a best-seller.[21]

- In 1971, May won the American Psychological Association's Distinguished Contribution to Science and Profession of Clinical Psychology award.

- In 1972, the New York Society of Clinical Psychologists presented him with the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Award for his book Power and Innocence (1972).

- In 1987, he received the American Psychological Foundation Gold Medal Award for Lifetime Contributions to Professional Psychology.

Influences and psychological background

[edit]May was influenced by North American humanism and interested in reconciling existential psychology with other philosophies, especially Freud's.

May considered Otto Rank (1884–1939) to be the most important precursor of existential therapy. Shortly before his death, May wrote the foreword to Robert Kramer's edited collection of Rank's American lectures. "I have long considered Otto Rank to be the great unacknowledged genius in Freud's circle", wrote May.[22]

May is often grouped with humanists, for example Abraham Maslow, who provided a good base for May's studies and theories as an existentialist. May delves further into the awareness of the serious dimensions of a human's life than Maslow did.

Erich Fromm had many ideas with which May agreed relating to May's existential ideals. Fromm studied the ways people avoid anxiety by conforming to societal norms rather than doing what they please. Fromm also focused on self-expression and free will, on all of which May based many of his studies.

May was Irvin D. Yalom's therapist.[23]

Stages of development

[edit]Like Freud, May defined certain "stages" of development. These stages are not as strict as Freud's psychosexual stages, rather they signify a sequence of major issues in each individual's life:

- Innocence – the pre-egoic, pre-self-conscious stage of the infant: An innocent is only doing what he or she must do. However, an innocent does have a degree of will in the sense of a drive to fulfill needs.

- Rebellion – the rebellious person wants freedom, but does not yet have a good understanding of the responsibility that goes with it.

- Ordinary – the normal adult ego learned responsibility, but finds it too demanding, so seeks refuge in conformity and traditional values.

- Creative – the authentic adult, the existential stage, self-actualizing and transcending simple egocentrism

The stages of development that Rollo May set out are not stages in the conventional sense (not in the strict Freudian sense) i.e. both children and adults can present qualities from these stages at different times.[24]

Aspects of the world

[edit]May's ideas about world aspects influenced his developmental theories. In total, there are three aspects:

The first, Umwelt, describes “the world around us.” This defines the biological or genetic influences of an individual, such influences are not conscious. Therefore, Umwelt teaches us about concepts like fate and destiny.[25] Next, the Mitwelt, describes “the world.” This includes the physical world where meaning is derived from constantly shifting relationships. This aspect of the world starts to influence us as children when we learn to manipulate others and are taught about the role of responsibility.[25] Finally, the Eigenwelt, describes our “own world.” This references the psychological realm where individuals related to themselves. This is where self-exploration, self-knowing, self-reflection, and self-identity are created. This aspect of the world is conscious, and it teaches us self-awareness.[25] Altogether, these aspects work together to shape our individualistic perception of the world and our environment.

Perspectives

[edit]Anxiety

[edit]In May's book The Meaning of Anxiety, he defined anxiety as "the apprehension cued off by a threat to some value which the individual holds essential to his existence as a self" (1967, p. 72). He quoted Kierkegaard: "Anxiety is the dizziness of freedom". May's interest in anxiety as a result of isolation grew while he was placed in a sanatorium for tuberculosis treatment. There, he saw patients exhibiting fear and anxiety that seemed to be linked to depersonalization and isolation.

From that experience, May concluded that anxiety is essential for individual growth. It is something that we cannot escape, thus we must use anxiety to develop our humanity and freely live a life of dignity.[26]

He thought that the feelings of threat and powerlessness associated with anxiety motivated humans to exercise freedom to act courageously instead of conforming to the comforts of modern life. Ultimately, anxiety created the opportunity for humans to live life to the fullest (Friedman). Additionally, May proposed that internalizing anxiety as fear could reduce overall anxiety because, “anxiety seeks to become fear”. He claimed that shifting anxiety to a fear incentivized avoiding a feared object or removing the fear of the object.[26]

Love

[edit]May's thoughts on love are documented in his book Love and Will, which addressed love and sex in human behavior. He asserted that society separated love and sex into two different ideologies when they should be classified as one. May identified five types of love:

- Libido: Biological function that can be satisfied through sexual intercourse or some other release of sexual tension.

- Eros: Psychological desire that seeks procreation or creation through an enduring union with a loved one.

- Philia: Intimate non-sexual friendship between two people.

- Agape: Esteem for the other, the concern for the other's welfare beyond any gain that one can get out of it, disinterested love, typically, the love of God for man.

- Manic: Impulsive, emotionally driven love. Feelings are very hot and cold. The relationship transitions between thriving and perfect, or bitter and ugly.

May investigated and criticized the "Sexual Revolution" in the 1960s, when individuals began to explore their sexuality. The term Free Sex replaced the ideology of free love. May postulated that love is intentionally willed by an individual; love reflects human instinct for deliberation and consideration. May then explained that giving in to sexual impulses did not actually make an individual free; freedom came from resisting sexual impulses. Unsurprisingly, May thought that Hippie counterculture as well as commercialization of sex and pornography influenced society to perceive a disconnect between love and sex. Because emotion had separated from reason, it became socially acceptable to seek sexual relationships while avoiding the natural drive to relate to another person and create new life. May thought that sexual freedom caused modern society to neglect important psychological developments such as the importance of caring.

Guilt

[edit]According to May, guilt occurs when people deny their potentialities, fail to perceive the needs of others or are unaware of their dependency on the world. Both anxiety and guilt include issues dealing with one's existence in the world. May mentioned they were ontological, meaning that they both refer to the nature of being and not to the feelings coming from situations. (Feist & Feist, 2008)[26]

Feist and Feist (2008) outline May's three forms of ontological guilt. Each form relates to one of the three modes of being, which are Umwelt, Mitwelt and Eigenwelt. Umwelt's form of guilt comes from a lack of awareness of one's existence in the world, which May presumed to take place when the world becomes more technologically advanced, and people are less concerned about nature and become removed from nature.

Mitwelt's form of guilt comes from failure to see things from other's point of view. Because we cannot understand the need of others accurately, we feel inadequate in our relations with them.

Eigenwelt's form of guilt is connected with the denial of our own potentialities or failure to fulfill them. This guilt is based in our relationship with the self. This form of guilt is universal because no one can completely fulfill their potentialities.

Criticism of modern psychotherapy

[edit]May thought thought that psychotherapists towards the end of the 20th century had fractured away from the Jungian, Freudian and other influencing psychoanalytic thought and started creating their own 'gimmicks' causing a crisis within the world of psychotherapy. These gimmicks were said to put too much stock into the self where the real focus needed to be looking at 'man in the world'. To accomplish this, May pushed for the use of existential therapy over individually created techniques for psychotherapy.[27]

May thought that modern psychotherapy in the late 20th century was branching away from its original founders: Freud, Jung, Rank, and Adler. May thought that modern psychotherapy isolated and ‘cured’ specific patient symptoms, called gimmicks. Typically, gimmicks are minor problems, not deep psychological issues, that emphasize the self. Ultimately, treating gimmicks puts the patient at a disadvantage by giving them a short-lasting fix, while distracting patients from their real problems. May also speculated that therapists become bored after two to three years of treating gimmicks which lead them to create more gimmicks. Dramatically, May asserted that gimmicks were designed to destroy modern society. In fact, May postulated that the work of many great philosophers is no longer relevant because they focused on gimmicks.[27]

Thus, May postulated that existential psychotherapy was the future of therapy. Existential psychotherapy aligned with the ideas of Freud, Jung, Rank, and Adler, who sought to bring the unconscious to the conscious. The conscious developed between age one and two, with the unconscious lying at the outer reaches of the conscious. Thus, existential psychotherapy helped patients to hone their mental capacities, allowing them to internalize their experiences; typically, in a more sensitive and intellectual manner. Existential psychotherapy also emphasized natural concepts like death, love, fear which relates to how individuals can fit into the world around them.[27]

In 1961, approximately two years after existential psychology became a recognized domain of psychology, Rollo May voiced his critiques of the ever-growing field. He identified concepts that he presumed would hinder the profession as it developed, he called these unconstructive trends. May identified five unconstructive trends:

- The idea the existential psychology could not be specialized to a particular group

- Existential psychology is not a form of therapy

- Existential psychology is not the same as Zen Buddhism

- The anti-scientific tendencies of existential psychiatry

- The widespread “wild eclecticism” would ruin modern therapy

First, May disliked the idea that existential psychology could be specialized to a particular school or group, namely the Ontoanalytic Society. This society analyzed what it meant to be human, or at least they tried to, which May thought would damage existential psychology. Not only was it empirically impossible to quantify, but it was also immoral to attempt. This analysis technique rationalized individual guilt so that the individual could feel relieved from whatever was troubling them; ultimately, May posited this process was removing the humility from the human experience. May's second unconstructive trend, which builds on first, emphasized that existential psychology is not a system of therapy. Rather it is an attitude towards human beings. Existential psychology seeks to understand the structure of human beings and their experiences.

Third, May thought the association of existential psychology with Zen Buddhism downplayed the significant differences between these two practices. Existential psychology brings awareness of existential problems like anxiety, tragedy, guilt, and the reality of evil. Attempting to bypass these problems using Zen Buddhist techniques would cause loss of the sense of self and loss of confidence in capacity for free will. May asserted that if we face problems head on, using existential psychology, then we make peace with them and assign them meaning.

Fourth, May detested the anti-scientific tendencies of psychologists practicing existential psychiatry. Such tendencies became popular alongside America's anti-intellectualism; a time period when distrust of reason was widespread. May argued against this, stating that science is a part of the universe, therefore, we must accept it.

Finally, May suggested the increase in “wild eclecticism” would ruin therapeutic practice. May thought wild eclecticism overemphasized therapeutic techniques (gimmicks) leading other existentialists to conclude that therapeutic techniques were unimportant to the therapy process. Conversely, May advocated for therapeutic techniques, as long as they held clear presuppositions, and were administered in an undogmatic manner because therapy was meant to be objective.

May also evaluated constructive trends in existential psychology, which May thought would further the understanding of existential psychology. May identified five constructive trends in existential psychology:

- Science's new approach to the study of man

- The central role of decision making in the human experience

- The problem of the ego

- How the senses are recognized as connecting man and the material world

- The concept of normal anxiety and normal guilt

First, May criticized science's new approach to the study of man. At that time, science focused heavily on the drives and forces that motivated human beings. Existential psychology, on the other hand, sought to evaluate whole human beings and their experiences. May asserted existentialists should focus on the man to whom a drive or force is happening and the subsequent experiences of acting willfully. In this manner, May hoped that existentialists would better understand anxiety, despair and other existential problems which rely on the totality of human experiences.

Second, May appreciated the central role of decision making in human experience. May perceived decision making as an inherent act of the centered self. Decisions cannot be made without consciousness, thus creating the experience freedom of choice. The act of assigning value was a distinct human characteristic.

Third, May evaluated the problem of the ego. Many psychologists assumed that the existential ego was associated with the psychoanalytical ego, which was false. May theorized that the existential ego worked alongside two other aspects, known as the aspects of the existing person. These aspects identify the self, the subjective center where personal bias is shaped by experience; the person, the social center where we can relate with other people; and the ego, our individual perception of how the self relates to the person.

May's final two constructive trends were less developed than his other trends. Simply, May agreed with two shifting paradigms within the psychology world. First, May liked how Dr. Erwin Straus identified the senses as a relationship between man and the world. Up until Dr. Straus's work, Pavlovian and Freudian ideologies of the western world insisted that the sense separated man from the natural world. Next, May praised the acceptance of normal anxiety within psychology. May, however, also emphasized the need to accept normal guilt. May thought that normal guilt heavily contributed to feelings of worthlessness. If not treated, neurotic guilt could occur.

Bibliography

[edit]| Year | Title | Published by | ISBN |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | The Springs of Creative Living | Whitmore & Stone | unknown |

| 1950[a] | The Meaning of Anxiety | W W Norton (1996 revised edition) | 0-393-31456-1 |

| 1953 | Man's Search for Himself | Delta (1973 reprint) | 0-385-28617-1 |

| 1956 | Existence | Jason Aronson (1994 reprint) | 1-56821-271-2 |

| 1965 | The Art of Counseling | Gardner Press (1989 revised edition) | 0-89876-156-5 |

| 1967 | Psychology and the Human Dilemma | W W Norton (1996 reprint) | 0-393-31455-3 |

| 1969 | Love and Will | W W Norton / Delta (1989 reprint) | 0-393-01080-5 / 0-385-28590-6 |

| 1972 | Power and Innocence: A Search for the Sources of Violence | W W Norton (1998 reprint) | 0-393-31703-X |

| 1973 | Paulus: A personal portrait of Paul Tillich | Harper & Row | 0-00-211689-8 |

| 1975 | The Courage to Create | W W Norton (1994 reprint) | 0-393-31106-6 |

| 1981 | Freedom and Destiny | W W Norton (1999 edition) | 0-393-31842-7 |

| 1983 | The Discovery of Being: Writings in Existential Psychology | W W Norton (1994 reprint) | 0-393-31240-2 |

| 1985 | My Quest for Beauty | Saybrook Publishing | 0-933071-01-9 |

| 1991 | The Cry for Myth | Delta (1992 reprint) | 0-385-30685-7 |

| 1995 | The Psychology of Existence[b] | McGraw-Hill | 0-07-041017-8 |

- ^ revised 1977.

- ^ with Kirk Schneider.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Paul Tillich as Hero: An Interview with Rollo May". Religion-online.org. Archived from the original on 2014-04-30. Retrieved 2012-10-21.

- ^ "Paul Tillich Resources". People.bu.edu. Retrieved 2012-10-21.

- ^ Kohn, Alfie (1984). "Existentialism Here and Now". The Georgia Review. 38 (2): 381–397. ISSN 0016-8386.

- ^ "Rollo May | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ a b Dempsey, David (1971-03-28). "Love and Will and Rollo May". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ a b "May, Rollo Reece | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ a b Bugental, James F. T. (1996). "Rollo May (1909–1994): Obituary". American Psychologist. 51 (4): 418–419. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.51.4.418.

- ^ [1] Archived May 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pace, Eric, "Dr. Rollo May Is Dead at 85; Was Innovator of Psychology", "The New York Times", October 4, 1994

- ^ May, Rollo (1967). The art of counseling. Internet Archive. Nashville, Tenn. : Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-0-687-01765-2.

- ^ May, Rollo (1979). Psychology and the human dilemma. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-01195-1.

- ^ May, Rollo (1969). Love and will (1st ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-01080-0.

- ^ May, Rollo (1972). Power and innocence: a search for the sources of violence (1. ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-01065-7.

- ^ May, Rollo (1973). Paulus: reminiscences of a friendship (1st ed.). New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-065535-8.

- ^ May, Rollo (1975). The courage to create. Ralph Ellison Collection (Library of Congress) (1st ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-01119-7.

- ^ May, Rollo (1981). Freedom and destiny: by Rollo May (1st ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-01477-8.

- ^ May, Rollo (1983). The discovery of being: Writings in existential psychology. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-01790-8.

- ^ May, Rollo (1985). My quest for beauty. San Francisco : New York, N.Y: Saybrook; Distributed by Norton. ISBN 978-0-933071-01-8.

- ^ May, Rollo (1991). The cry for myth (1. ed.). New York, NY: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-02768-6.

- ^ Schneider, Kirk J.; May, Rollo (1995). The psychology of existence: an integrative, clinical perspective. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-041017-6.

- ^ "Ralph Waldo Emerson Award Winners". PBK. Retrieved 2022-06-27.

- ^ (Rank, 1996, p. xi).

- ^ Serlin, I. (1994). Remembering Rollo May: An interview with Irvin Yalom. The Humanistic Psychologist, 22(3), 268–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873267.1994.9976954

- ^ Ellis, Albert; Abrams, Mike; Abrams, Lidia (2008-08-14). Personality Theories: Critical Perspectives. SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4522-6472-1.

- ^ a b c Cottle, Thomas (2002). "The beginning, end, and in between of adolescence". Midwest Quarterly. 44 (1): 63–75.

- ^ a b c Feist, Jess; Feist, Gregory (15 July 2008). Theories of Personality. McGraw-Hill Education.

- ^ a b c Schneider, Kirk J.; Galvin, John; Serlin, Ilene (2009-07-09). "Rollo May on Existential Psychotherapy". Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 49 (4): 419–434. doi:10.1177/0022167809340241. ISSN 0022-1678. S2CID 145539081.

- ^ a b May, Rollo (1961). "Existential Psychiatry an Evaluation". Journal of Religion and Health. 1 (1): 31–40. doi:10.1007/BF01532010. ISSN 0022-4197. JSTOR 27504465. S2CID 29403684.

Sources and further reading

[edit]- Bohart, Arthur C.; Held, Barbara S.; Mendelowitz, Edward; Schneider, Kirk J., eds. (2013). Humanity's Dark Side: Evil, Destructive Experience, and Psychotherapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. ISBN 9781433811814.

- Hoffman, Louis; Yang, Mark; Kaklauskas, Francis J.; Chan, Albert, eds. (2009). Existential Psychology East-West. Colorado Springs: University of the Rockies Press. ISBN 9780976463863.

- De Castro, Alberto (2011). An Integration of the Existential Understanding of Anxiety in the Writings of Rollo May, Irvin Yalom, and Kirk Schneider (PhD dissertation). Saybrook University. ProQuest 761129675.

- May, Rollo (1974). "Rollo May on the Courage to Create". Media and Methods. 10 (9): 14–16.

- Rank, Otto (1996). Kramer, Robert (ed.). A Psychology of Difference: The American Lectures. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-04470-8.

- Friedman, Howard S.; Schustack, Miriam W. (2012). Personality: Classic Theories and Modern Research. Boston: Pearson Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 9780205050178.