Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Standard-definition television

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2022) |

Standard-definition television (SDTV; also standard definition or SD) is a television system that uses a resolution that is not considered to be either high or enhanced definition.[1] Standard refers to offering a similar resolution to the analog broadcast systems used when it was introduced.[1][2]

History and characteristics

[edit]SDTV originated from the need for a standard to digitize analog TV (defined in BT.601) and is now used for digital TV broadcasts and home appliances such as game consoles and DVD disc players.[3][4]

Digital SDTV broadcast eliminates the ghosting and noisy images associated with analog systems. However, if the reception has interference or is poor, where the error correction cannot compensate one will encounter various other artifacts such as image freezing, stuttering, or dropouts from missing intra-frames or blockiness from missing macroblocks. The audio encoding is the last to suffer a loss due to the lower bandwidth requirements.[citation needed]

Standards that support digital SDTV broadcast include DVB, ATSC, and ISDB.[5] The last two were originally developed for HDTV, but are also used for their ability to deliver multiple SD video and audio streams via multiplexing.

PAL and NTSC

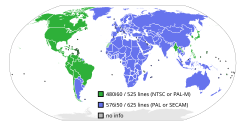

[edit]The two SDTV signal types are 576i (with 576 interlaced lines of resolution,[6] derived from the European-developed PAL and SECAM systems), and 480i (with 480 interlaced lines of resolution,[3] based on the American NTSC system). SDTV refresh rates are 25, 29.97 and 30 frames per second, again based on the analog systems mentioned.

In North America, digital SDTV is broadcast in the same 4:3 fullscreen aspect ratio as NTSC signals, with widescreen content often being center cut.[5]

In other parts of the world that used the PAL or SECAM color systems, digital standard-definition television is now usually shown with a 16:9 aspect ratio, with the transition occurring between the mid-1990s and late-2000s depending on the region. Older programs with a 4:3 aspect ratio are broadcast with a flag that switches the display to 4:3. Some broadcasters prefer to reduce the horizontal resolution by anamorphically scaling the video into a pillarbox.[citation needed]

Pixel aspect ratio

[edit]| Video format | Display aspect ratio (DAR) | Resolution | Pixel aspect ratio (PAR) | After horizontal scaling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 480i | 4:3 | 704 × 480 (horizontal blanking cropped) | 10:11 | 640 × 480 |

| 720 × 480 (full frame) | 655 × 480 | |||

| 480i | 16:9 | 704 × 480 (horizontal blanking cropped) | 40:33 | 854 × 480 |

| 720 × 480 (full frame) | 873 × 480 | |||

| 576i | 4:3 | 704 × 576 (horizontal blanking cropped) | 12:11 | 768 × 576 |

| 720 × 576 (full frame) | 788 × 576 | |||

| 576i | 16:9 | 704 × 576 (horizontal blanking cropped) | 16:11 | 1024 × 576 |

| 720 × 576 (full frame) | 1050 × 576 |

The pixel aspect ratio is the same for 720- and 704-pixel resolutions because the visible image (be it 4:3 or 16:9) is contained in the center 704 horizontal pixels of the digital frame. In the case of a digital video line having 720 horizontal pixels (including horizontal blanking), only the center 704 pixels contain the actual 4:3 or 16:9 image, and the 8-pixel-wide stripes on either side are called nominal analog blanking or horizontal blanking and should be discarded when displaying the image. Nominal analog blanking should not be confused with overscan, as overscan areas are part of the actual 4:3 or 16:9 image.

For SMPTE 259M-C compliance, an SDTV broadcast image is scaled to 720 pixels wide for every 480 NTSC (or 576 PAL) lines of the image with the amount of non-proportional line scaling dependent on either the display or pixel aspect ratio. Only 704 center pixels contain the actual image and 16 pixels are reserved for horizontal blanking, though a number of broadcasters fill the whole 720 frames.[citation needed] The display ratio for broadcast widescreen is commonly 16:9 (pixel aspect ratio of 40:33 for anamorphic); the display ratio for a traditional or letterboxed broadcast is 4:3 (pixel aspect ratio of 10:11).

An SDTV image outside the constraints of the SMPTE standards requires no non-proportional scaling with 640 pixels (defined by the adopted IBM VGA standard) for every line of the image. The display and pixel aspect ratio is generally not required with the line height defining the aspect. For widescreen 16:9, 360 lines define a widescreen image and for traditional 4:3, 480 lines define an image.

See also

[edit]- Digital Audio Broadcasting – Digital radio standard

- Moving Picture Experts Group – Alliance of working groups for multimedia coding

- Rec. 601 – Standard from the International Telecommunication Union

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Standard definition television (SDTV)". ATSC: NextGen TV. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ^ "HDTV". siliconimaging.com. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ^ a b "What means 480i?". afterdawn.com.

- ^ "BT.601: Studio encoding parameters of digital television for standard 4:3 and wide screen 16:9 aspect ratios". ITU.

- ^ a b "All-Digital Television Is Coming (And Sooner Than You Think!)". Federal Communications Commission. Archived from the original on Sep 29, 2008.

- ^ "What means 576i?". Afterdawn.com.